Aida Overton Walker: Glamour on The Stage – a century ago

Posted: February 14, 2014 Filed under: English | Tags: Aida Overton Walker, Black History Month Comments Off on Aida Overton Walker: Glamour on The Stage – a century agoAida Overton Walker (February 14th, 1880 – 1914) dazzled early 20th century American audiences with her original dance routines, an enchanting singing voice, and a penchant for elegant costumes. She was one of the premiere African-American women artists from the end of The Gilded Age, the Cake-Walk era, the dawn of Jazz’s birth. In addition to her alluring stage persona and acclaimed performances, she won the hearts of Black entertainers for numerous benefit performances near the end of her all-too-brief life. She was, in the words of the New York Age‘s Lester Walton, the exponent of “clean, refined artistic entertainment.”

.

Born in Richmond, Virginia, Aida Overton grew up in New York City, where she gained an education and considerable musical training. At the age of fifteen, she joined John Isham’s Octoroons, a Black touring group of the 1890s, and the following year she became a member of The Black Patti Troubadours. Although these shows consisted of dozens of performers, Overton emerged as one of the most promising “soubrettes” of her day. In 1898, she joined the company of the famous comedy team Bert Williams and George Walker, appearing in all of their extravaganzas—The Policy Players (1899), The Sons of Ham (1900), In Dahomey (1903), Abyssinia (1905), and Bandanna Land (1907). Within about a year of their meeting, George Walker and Overton had married and before long became the most admired of African-American couples on stage.

.

While George Walker supplied most of the ideas for the musical comedies and Bert Williams enjoyed fame as the “funniest man in America,” it was Aida who became the indispensable member of the Williams and Walker Company. In The Sons of Ham, for example, her rendition of Hannah from Savannah won praise for combining superb vocal control with acting skill that together presented a strong image of Black womanhood. Indeed, onstage Aida refused to comply with the “Plantation image” of Black women as plump Mammies, happy to serve; like her husband, she viewed the representation of refined African-American types on the stage as important political work. A talented dancer, Aida improvised original routines that her husband eagerly introduced in their shows; when In Dahomey played in England, Aida proved to be its strongest attraction. Society women invited her to their homes for private lessons in the exotic Cake Walk that the Walkers had included in the show. After two seasons in England, the company returned to the United States in 1904, and Aida was featured in a New York Herald interview about their tour. At times Walker asked his wife to interpret dances made famous by other performers—one example being the “Salome” dance that took Broadway by storm in the early 1900s.

After a decade of nearly continuous success with the Williams and Walker Company, Aida’s career took an unexpected turn when her husband collapsed on tour with Bandanna Land. Initially Walker returned to his boyhood home of Lawrence, Kansas, where his mother cared for him. In his absence, Aida took over many of his songs and dances to keep the company together. In early 1909, however, Bandanna Land was forced to close, and Aida temporarily retired from stage work to care for her husband, now seriously ill. No doubt recognizing that he would not recover and that she alone must support the family, she returned to the stage in Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson’s Red Moon in the autumn of 1909, and she joined the Smart Set Company in 1910. Aida also began touring the Vaudeville circuit as a solo act. Less than two weeks after Walker’s death in January 1911, she signed a two-year contract to appear as a co-star with S. H. Dudley in another all-Black traveling show.

Although still a relatively young woman in the early 1910s, Aida began to develop medical problems that limited her capacity for constant touring and stage performance. As early as 1908, she had organized benefits to aid such institutions as the Industrial Home for Colored Working Girls, and after her contract with S. H. Dudley expired, she devoted more of her energy to such projects, which allowed her to remain in New York City. She also took an interest in developing the talents of younger women in the profession, hoping to pass along her vision of Black performance as refined and elegant. She produced shows for two such female groups in 1913 and 1914—the Porto Rico Girls and the Happy Girls. She encouraged them to “work up” original dance numbers and insisted that they don stylish costumes on stage.

.

When Aida Overton Walker died suddenly of kidney failure on October 11, 1914, the African–American entertainment community in New York went into deep mourning. The New York Age featured a lengthy obituary on its front page, and hundreds of people descended on her residence to confirm a story they hoped was untrue. Walker left behind a legacy of polished performances and model professionalism. Her demand for respect – and her generosity – made her a belovéd figure in African-American theater circles.

Reprinted from:

Jazz: Black Musical Theater in New York, 1890-1915. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989, Thomas L Riis

. . . . .

Frank Marshall Davis: “Cuatro Ojeadas de Noche” y “Auto-Retrato” / “Four Glimpses of Night” and “Self-Portrait”

Posted: February 12, 2014 Filed under: English, Frank Marshall Davis, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: Black History Month, El Mes de la Historia Afroamericana Comments Off on Frank Marshall Davis: “Cuatro Ojeadas de Noche” y “Auto-Retrato” / “Four Glimpses of Night” and “Self-Portrait”Frank Marshall Davis (1905-1987)

“Cuatro Ojeadas de Noche”

.

I

.

Ansiosamente

como una mujer que se apura por su amante

La Noche llega en el cuarto del mundo

y se extiende, tierna y satisfecha

contra el rostro fresco y redondo

de la luna.

.

II

.

La Noche es un niño curioso,

vagabundeando entre tierra y cielo,

entrando a hurtadillas por las ventanas y puertas,

pintarrajeando morado

el barrio entero.

El Día es

una madre humilde y modesta

siguiendo con una toallita en la mano.

.

III

.

Yendo puerta a puerta

La Noche vende

bolsas negras de estrellas de menta,

un montón de cucuruchos de luna-vainilla

hasta que

sus bienes están acabados,

pues arrastra los pies de camino a casa,

tintineando las monedas grises del alba.

.

IV

.

El canto quebradizo de la Noche,

hecho de plata, aflautado,

destroza en mil millones de fragmentos de

sombras silenciosas

con el estrépito del jazz

de un sol madrugador.

. . .

Frank Marshall Davis (1905-1987)

“Four Glimpses of Night”

.

I

.

Eagerly

Like a woman hurrying to her lover

Night comes to the room of the world

And lies, yielding and content

Against the cool round face

Of the moon.

.

II

.

Night is a curious child, wandering

Between earth and sky, creeping

In windows and doors, daubing

The entire neighbourhood

With purple paint.

Day

Is an apologetic mother

Cloth in hand

Following after.

.

III

.

Peddling

From door to door

Night sells

Black bags of peppermint stars

Heaping cones of vanilla moon

Until

His wares are gone

Then shuffles homeward

Jingling the grey coins

Of daybreak.

.

IV

.

Night’s brittle song, sliver-thin,

Shatters into a billion fragments

Of quiet shadows

At the blaring jazz

Of a morning sun.

. . .

“Auto-Retrato” (del poemario Humores negros, 1948)

.

Yo sería

un pintor con palabras,

creando retratos ingeniosos

sobre el lienzo amplio de tu mente,

imágenes de esas cosas

moldeados por mis ojos

– algo que me interesa;

pero, porque soy un Décimo Americano

en esta democracia,

bosquejo una miniatura

aunque contraté por un mural.

.

Claro,

Entiendes esta democracia;

Un hombre es bastante bueno como el otro

– de una cabaña de troncos hasta La Casa Blanca –

– de chico pobre hasta presidente de una empresa –

Hoover y Browder, cada uno con un voto;

en un país libre;

con completa igualdad;

Ah SÍ…

– Y los ricos reciben devoluciones de la renta y

los pobres obtienen cheques de asistencia.

.

¿Y YO?

Pago cinco centavos por un sumario de los sucesos del momento;

veinticinco centavos por lo último sobre Hollywood;

tuerzo el dial por “Stardust” o Shostakovich;

y con mi talón de gradería guardo el derecho a gritar: “¡Mata’l cabrón!” al árbitro.

Pues, ¿por qué soy diferente a los nueve otros Americanos?

.

Pero escúchame, tú:

No te preocupes por mí

– porque tengo rango.

Soy el converso número 4711 de la Iglesia Bautista Beulah;

Soy Seguridad Social número 337-16-3458 en Washington;

¡Gracias, Señor Dios y Señor Roosevelt!

Y hay algo más que te quiero decir:

No importa lo que pasa…

¡Yo también puedo hacer señas a un policía!

. . .

“Self-Portrait” (from Black Moods, published 1948)

.

I would be

A painter with words

Creating sharp portraits

On the wide canvas of your mind

Images of those things

Shaped through my eyes

That interest me;

But being a Tenth American

In this democracy

I sometimes sketch a miniature

Though I contract for a mural.

.

Of course

You understand this democracy;

One man as good as another,

From log cabin to White House,

Poor boy to corporation president,

Hoover and Browder with one vote each,

A free country,

Complete equality—

Yeah—

And the rich get tax refunds,

The poor get relief cheques.

.

As for myself

I pay five cents for a daily synopsis of current history,

Two bits and the late low-down on Hollywood,

Twist a dial for “Stardust” or Shostakovich,

And with each bleacher stub I reserve the right to shout “Kill the bum!” at the umpire—

Wherefore am I different

From nine other Americans?

.

But listen, you:

Don’t worry about me

– I rate!

I’m Convert 4711 at Beulah Baptist Church,

I’m Social Security No. 337-16-3458 in Washington,

Thank you Mister God and Mister Roosevelt!

And another thing:—

No matter what happens

I too can always call in a policeman!

.

.

.

Traducción del inglés / Translation into Spanish: Alexander Best

. . . . .

Sterling Allen Brown: “She jes’ gits hold of us dataway”

Posted: February 11, 2014 Filed under: English: Nineteenth-century Black-American Southern Dialect, Sterling A. Brown | Tags: Black History Month, Ma Rainey Comments Off on Sterling Allen Brown: “She jes’ gits hold of us dataway”

The family pictured here was part of The Great Migration: African-Americans on the move from the rural South up or over to towns and cities of the North and MidWest. They wished to escape that Life of which Ma Rainey sang…

Sterling Allen Brown (1901-1989)

“Ma Rainey” (1932)

.

I

When Ma Rainey

Comes to town,

Folks from anyplace

Miles aroun’,

From Cape Girardeau,

Poplar Bluff,

Flocks in to hear

Ma do her stuff;

Comes flivverin’ in,

Or ridin’ mules,

Or packed in trains,

Picknickin’ fools. . . .

That’s what it’s like,

Fo’ miles on down,

To New Orleans delta

An’ Mobile town,

When Ma hits

Anywheres aroun’.

.

II

Dey comes to hear Ma Rainey from de little river settlements,

From blackbottorn cornrows and from lumber camps;

Dey stumble in de hall, jes a-laughin’ an’ a-cacklin’,

Cheerin’ lak roarin’ water, lak wind in river swamps.

An’ some jokers keeps deir laughs a-goin’ in de crowded aisles,

An’ some folks sits dere waitin’ wid deir aches an’ miseries,

Till Ma comes out before dem, a-smilin’ gold-toofed smiles

An’ Long Boy ripples minors on de black an’ yellow keys.

.

III

O Ma Rainey,

Sing yo’ song;

Now you’s back

Whah you belong,

Git way inside us,

Keep us strong. . . .

O Ma Rainey,

Li’l an’ low;

Sing us ’bout de hard luck

Roun’ our do’;

Sing us ’bout de lonesome road

We mus’ go. . .

.

IV

I talked to a fellow, an’ the fellow say,

“She jes’ catch hold of us, somekindaway.

She sang Backwater Blues one day:

‘It rained fo’ days an’ de skies was dark as night,

Trouble taken place in de lowlands at night.

‘Thundered an’ lightened an’ the storm begin to roll

Thousan’s of people ain’t got no place to go.

‘Den I went an’ stood upon some high ol’ lonesome hill,

An’ looked down on the place where I used to live.’

An’ den de folks, dey natchally bowed dey heads an’ cried,

Bowed dey heavy heads, shet dey moufs up tight an’ cried,

An’ Ma lef’ de stage, an’ followed some de folks outside.”

Dere wasn’t much more de fellow say:

She jes’ gits hold of us dataway.

. . .

“Ma Rainey” from The Collected Poems of Sterling A. Brown, edited by Sterling A. Brown. © 1932

Ma Rainey with her band in 1923_Eddie Pollack_Albert Wynn_Thomas A. Dorsey_Dave Nelson_Gabriel Washington

. . . . .

“Lift Every Voice and Sing” & Augusta Savage’s “The Harp”

Posted: February 10, 2014 Filed under: English, James Weldon Johnson | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on “Lift Every Voice and Sing” & Augusta Savage’s “The Harp”“Lift Every Voice and Sing” is a song first written as a poem in 1899 by James Weldon Johnson (1871-1938). It was Weldon’s brother John Rosamond Johnson who set the poem to music. The poem was first spoken aloud by several hundred schoolchildren on February 12th, 1900, at the segregated Stanton School in Jacksonville, Florida, where James Johnson was principal. The recital of the new poem was meant to honour both visiting guest Booker T. Washington – and Abraham Lincoln, whose birth date fell on the same day.

. . .

Lift every voice and sing, till earth and heaven ring,

Ring with the harmonies of liberty;

Let our rejoicing rise, high as the listening skies,

Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

.

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us;

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

Let us march on till victory is won.

.

Stony the road we trod, bitter the chastening rod,

Felt in the days when hope unborn had died;

Yet with a steady beat, have not our weary feet

Come to the place for which our fathers sighed?

.

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered,

We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered;

Out from the gloomy past, till now we stand at last

Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.

.

God of our weary years, God of our silent tears,

Thou Who hast brought us thus far on the way;

Thou Who hast by Thy might, led us into The Light,

Keep us forever in the path, we pray.

.

Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we met Thee;

Lest our hearts, drunk with the wine of the world, forget Thee;

Shadowed beneath Thy hand, may we forever stand,

True to our God, true to our native land.

. . .

Augusta Savage (1892-1962), a Florida sculptor (born near Jacksonville) who grew artistically / worked in New York City during The Harlem Renaissance, was commissioned in 1939 to do a monumental plaster work for the New York World’s Fair. “The Harp” was strongly influenced by James Weldon Johnson’s poem “Lift Every Voice and Sing”. The 16-foot tall piece was exhibited outside the Contemporary Arts building where it received much acclaim. The sculpture depicted twelve stylized Black singers of graduated heights that symbolized the strings of the harp. The sounding board was formed by the hand and arm of God, and a kneeling man holding music represented the foot pedal. No funds were made available to cast “The Harp” in permanent bronze, nor were there any facilities to store it. After the World’s Fair was over, “The Harp” was demolished, like most of the event’s art.

. . . . .

Hale Woodruff’s “Afro Emblems” and Ashanti Gold Weights

Posted: February 10, 2014 Filed under: IMAGES | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Hale Woodruff’s “Afro Emblems” and Ashanti Gold WeightsHale Aspacio Woodruff (Cairo, Illinois, USA, 1900-1980) first grew interested in African art in the 1920s, when an art dealer gave him a German book on the subject. He couldn’t read the text but appreciated studying the pictures; on a trip to Europe some years later he bought African sculpture for his own personal inspiration. For “Afro Emblems”, Woodruff divided his canvas into rough rectangles, filling each shape with an emblem inspired by Ashanti or Akan gold weights. [ See paragraph below. ] Woodruff’s bold black outlines and dashes of colour stand out from the blue background, creating an abstract African-influenced pattern.

Ashanti or Akan Gold Weights

.

Natural gold resources in the dense forests of southern Ghana brought wealth and influence to the Ashanti (Asante) people. Wealth increased by transporting gold to North Africa via trade routes across the Sahara Desert. In the 15th and 16th centuries this gold attracted other traders, from the great Songhay Empire (in today’s Republic of Mali), from the Hausa cities of northern Nigeria and from Europe. European interest in the region, initially in gold and then in enslaved Africans, brought about great changes, not least the creation of the British Gold Coast Colony in the 19th century. (In 1959, this “Colony” de-Colonized, becoming the modern West-African nation of Ghana.)

.

Asante State had grown out of a group of smaller states to become a centralized hierarchical kingdom. By the early 1700s the Asante State’s increased power meant it was able to displace the former dominant state, Denkyira, which had, through conquest, controlled major trade routes to the Atlantic coast as well as some of the richest gold mines. Once the Asante became dominant in this region, both gold and slaves passed through its state capital, Kumasi.

Gold was central to Asante art and belief. Gold entered the Asante court via tribute or war and was fashioned into jewellery and ceremonial objects there by artisans from conquered territories. The court’s power was further demonstrated through its regulation of the regional gold trade. Everyone involved in trade and commerce owned, or had access to, a set of weights and scales. The weights, produced in brass, bronze or copper (usually by the ‘lost wax’ process), corresponded to a standardized weight system derived from North African / Islamic, Dutch and Portuguese precedents. Since each weight had a known measurement, merchants too employed them for secure, fair-trade arrangements with one another. Other gold-trade equipment included shovels for scooping up gold dust, spoons for lifting gold dust from the shovel and putting it on the scales and boxes for storing gold dust.

. . .

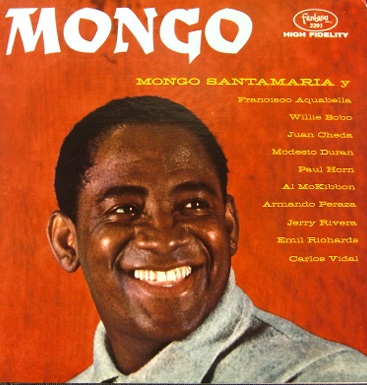

Mongo Santamaría and his ritmo sabroso: Africa aslant yet Africa strong

Posted: February 10, 2014 Filed under: English | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Mongo Santamaría and his ritmo sabroso: Africa aslant yet Africa strong. . .

The Quinto is the lead drum (tumbadora in Cuba, conga elsewhere) used in the various forms of Afro-Cuban Rumba. It is also the smallest of the three. These drums – of Cuban slave-hybridized Bantu-Congolese / Lucumi-Yoruba origin – are tall (though the Quinto may be only one foot tall), narrow, and single-headed. The Cuban version of such tumbadoras is staved, like a barrel; it may have originated from salvaged barrels at one time. Rumba-quinto master and Latin-Jazz percussionist Ramón “Mongo” Santamaría Rodríguez (Havana, Cuba, 1922 – February 1st, 2003) demonstrated his creative skill on the Quinto in the classic 1959 recording Mazacote (“Sweet hodgepodge”):

.

To read “I Want to Be a Drum” by Mozambican poet José Craveirinha click the link below:

O Festival Internacional do Tambor Muhtadi: “Quero ser tambor” / “I want to be a drum”

. . . . .

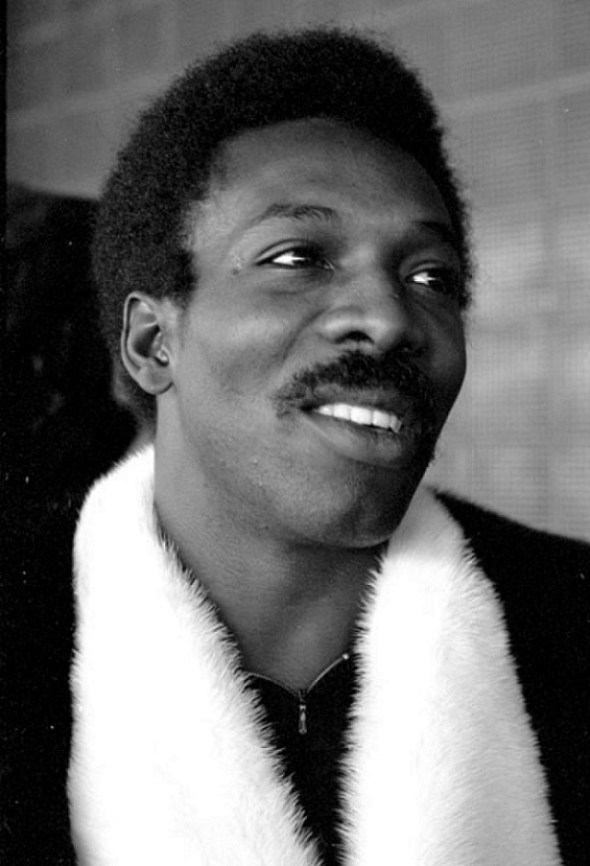

Wilson Pickett: Engine Number 9

Posted: February 9, 2014 Filed under: IMAGES | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Wilson Pickett: Engine Number 9Wilson Pickett (1941-2006) was born in Alabama into a family of many kids, and a father who was working up in Detroit, Michigan. In an interview in later years Pickett described his mother during his childhood: “She was the baddest woman – in my book. I get scared of her even now. She used to hit me with anything, skillets, stove wood… One time I ran away and cried for a week. Stayed in the woods, me and my little dog.” When he was fourteen he headed up to Detroit and lived with his father. It was then that he seriously began to sing in church ensembles that toured around; one of them, The Violinaires, helped him to really hone his singing skills. Gospel singers were beginning to “cross over” into the secular music market and this transition led the way to what would come to be known as Soul music. The Falcons, with Eddie Floyd, were at the forefront of this evolution, and Pickett joined the group at the age of 18 in 1959. His first songwriting began, with “I Found a Love”. “If You Need Me” and “It’s Too Late” would follow – but the latter two he recorded solo – commencing a career under his own name. James Brown is undisputably Soul’s Number 1 Man, but if you listen to Pickett and Brown, Pickett’s voice is undeniably more interesting: complex; capable of bird-like shrieks and astonishing wails; hoarse from crying? shouting? at Love gone wrong or Love going oh so good. James Brown had the crazy looks and stage personality, but Pickett’s voice is richer, takes more chances, and makes the weirdest deep-from-within sounds.

.

Listen to Wilson Pickett in this 1970 recording of Leon Gamble and Kenny Huff’s “Engine Number 9”. The instrumental sound is a hybrid of Blues and Rock. And Pickett’s voice is all Soul:

. . .

“Engine, Engine number 9”

(words and music by Leon Gamble and Kenny Huff / Owws and Uhs by The Wicked Pickett!)

.

Engine, engine, number 9:

Can you get me back on time?

Move on, move on down the track,

Keep that steam comin´ out your stack.

Huh! Keep on movin´,

Keep on movin´, keep on movin´…

Oww! Uh!

.

Engine, engine, number 9:

Keep on movin´ down the line.

Seems like I been gone for days,

I can´t wait to see my baby´s face.

Look-a-here: Been so long since I held her,

Been so long since I held her…

Oww!

.

Been so long since I held her,

Been so long since I kissed her…

Owwww!

Engine, engine, number 9:

Move on, move on down the line.

Seems like I been gone for days,

I can´t wait to see my baby´s face.

Move on, move on, woaaah, move on!

Owwwww! Gotta git there…

[ Oh, this is soundin’ alright…

I think I’m gonna hold it a little bit longer,

I’m gonna let the boys “cook” this a little bit… ]

Etcetera…

. . . . .

Johnny Hartman: the great yet little known song stylist

Posted: February 9, 2014 Filed under: IMAGES | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Johnny Hartman: the great yet little known song stylistJohnny Hartman (born John Maurice Hartman), 1923-1983, was from Louisiana but grew up in Chicago. Imagine the best qualities of Frank Sinatra’s voice from the 1940s and 1950s – tender and thoughtful, or manly with confidence – and you’ll have an idea of Hartman’s voice. Now: lower that voice to a baritone-bass – and you’ve got Hartman. Like Sinatra, he had a homely face and a great voice – but Hartman’s interpretive skills with a ballad were more sensitive – were finer – than Sinatra’s.

.

Contemporary singer Gregory Generet has written of Hartman: “ [He] was a master of emotional expression, putting everything he had into every word he sang. His rich, masculine baritone voice never wavered in its sincerity. The only vocalist ever to record with John Coltrane, he was mostly known only to true jazz lovers during his glorious career.” Generet’s correct when he writes “glorious”; he’s also correct when he writes “mostly known only to true jazz lovers.” Hartman’s performances on record are “glorious” and he was always too little known by the general public, and is by now all but eclipsed in the Internet-era that is the 21st century, where History is 10 years ago.

. . .

Cole Porter (1891-1964)

“Down in the Depths on the 90th floor” (1936)

.

Manhattan, I’m up a tree,

The one I’ve most adored

Is bored

With me.

Manhattan, I’m awfully nice,

Nice people dine with me,

And sometimes twice.

Yet the only one in the world I’m mad about

Talks of somebody else

– And walks out.

.

With a million neon rainbows burning below me

And a million noisy taxis raising a roar,

Here I stand above the town

Drinking champagne with a frown,

Down in the depths on the ninetieth floor.

.

And the crowds in all the nightclubs punish the parquet

And the couples at the bar clamour for more.

I’m deserted and depressed

In my regal eagle’s nest,

Down in the depths on the ninetieth floor.

.

When the only one you want wants another,

What’s the good of swank and cash in the bank galore?

Why, my janitor and his wife,

They have a perfectly good love life;

And here am I,

Facing tomorrow,

Alone in my sorrow

– Down in the depths on the ninetieth floor!

. . .

Listen to this 1955 recording of Johnny Hartman singing “Down in the Depths (on the 90th floor)”:

. . . . .

Black History Month: Favourite Albums: 1933 –1983

Posted: February 7, 2014 Filed under: IMAGES | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Black History Month: Favourite Albums: 1933 –1983Though Zócalo Poets is a poetry site – mainly – we are unable to resist the urge to post a Favourites list. Not a list of poems but of musical recordings; some of these are Songs, and, therefore, related to Poetry in its origins…What’s not to love about such an undertaking?!

Our Favourite Albums list for Black History Month 2014 is by no means definitive, for Music, like Poetry, is a limitless lifetime’s discovery. But here at least are some “snowed-in” Bests for February in Toronto…

. . .

Art Tatum (1909-1956) was one of the greatest piano virtuosos of the twentieth century. His musical aptitude didn’t emerge from nowhere, however; his father Arthur and his mother Mildred were a guitarist and pianist together at Grace Presbyterian Church in Toledo, Ohio. From early childhood, Art Tatum’s perfect pitch and ability to play by ear got him a head start; he would come to touch the piano keyboard as if it were merely an extension of his fingertips. His main influences were James P. Johnson, Fats Waller, and Earl Hines. But Tatum goes beyond them all – great though they were. His first piano recordings, both from 1933, are breathtaking in their sophistication, ease, sensitivity, and light touch: “Tiger Rag” and “Tea for Two”.

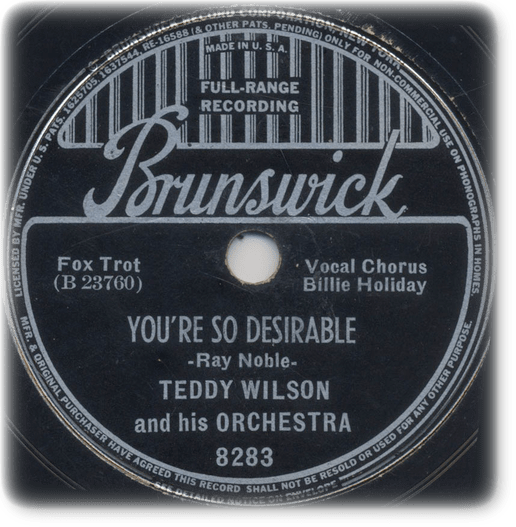

Since there is no one album for Billie Holiday in the 1930s – generally there were only individual 78 rpm records with one song per side during that era – we have chosen her 1938 recording of Ray Noble’s “You’re So Desirable”. The 23-year-old Holiday sings it just right. And it was during this period – her early years – that she did her best singing. She was billed as the vocalist for various popular orchestras of the day – and was among the first singers to become more of a draw in performance than the band itself. From the time she was 18 and made her first recorded song – “My Mother’s Son-in-law”(1933), and clear through till the end of the decade, in songs such as “Travelin’ All Alone”(1937) and “On the Sentimental Side”(1938), Billie sang in her own new way – cheerful, spritely, yet also kind of lost: dreamy and sad – and often about a quarter-beat behind the band’s beat.

Paul Robeson recorded “Trees”, a song adaptation of a terrifically popular 1913 poem by Joyce Kilmer, in 1938 when he was 40 years old. Robeson’s voice was the deepest – yet full of nuanced feeling for all its bass ballast. A magnificent singer.

And take a few minutes to research his ambitious and complicated life. Robeson was a man of integrity; he really put his money where his mouth was – and paid the price.

Mongo Santamaría‘s 1959 album “Mongo”. Santamaría was a Cuban conga player, primarily handling the “quinto” drum which voices the lead in a percussion ensemble. Afro-Blue and Mazacote (“Sweet Hodgepodge”) are hypnotic tracks.

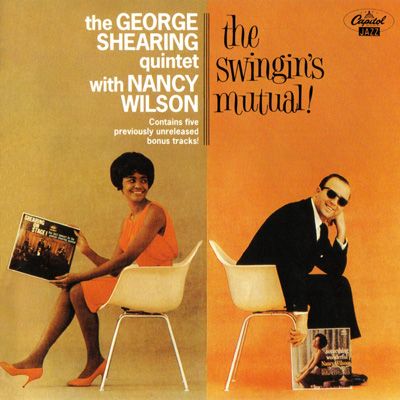

Nancy Wilson was 24 years old when she sang on this 1961 record, backed by George Shearing. To hear her sing “On Green Dolphin Street” is to hear young-smart-&-sophisticated. But in all that she sang from the 1960s – the pop standards, too – Wilson’s unique sound included a vocal clarity and precision unlike any other singer. The Song-Stylist to match!

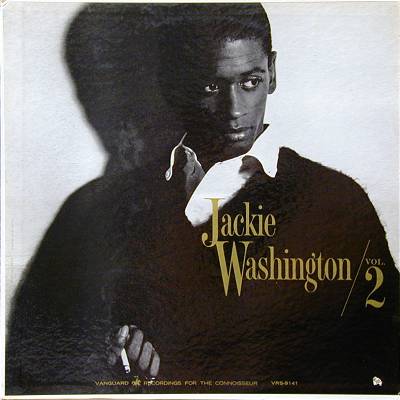

Jackie Washington – born Juan Cándido Washington y Landrón in Puerto Rico but raised in Boston – was mainly known on the folk-music scene. He sang in English and in Spanish. This 1963 record includes “The Water is Wide” and “La Borinqueña”. A subtle and much under-rated singer.

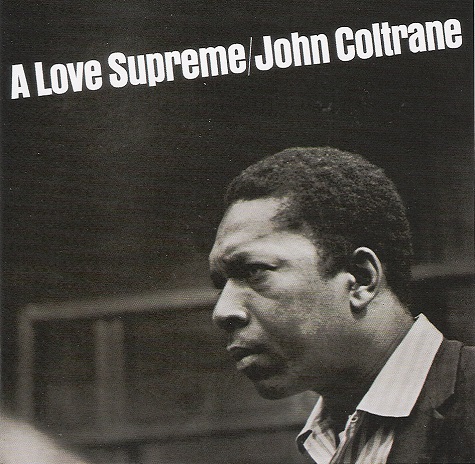

The John Coltrane Quartet recorded A Love Supreme in just one session, on December 9th, 1964. It is a four-part instrumental suite – complex jazz, both introspective and forthright. Personnel included: Jimmy Garrison, Elvin Jones, and McCoy Tyner.

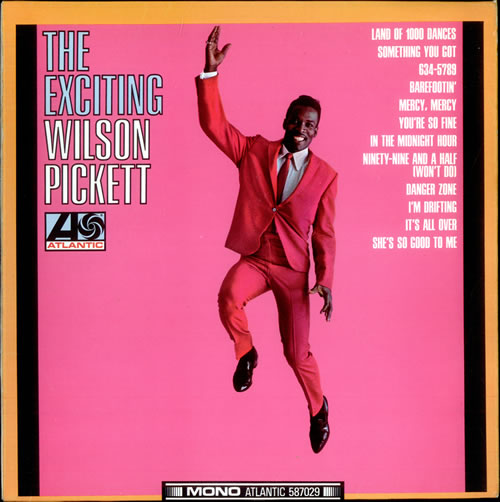

Wilson Pickett was one of the great R & B and Soul singers of the 1960s. And his earthy, rough and intense tone brings any lyric to life. The Exciting Wilson Pickett, from 1966, is 12 songs that play like jukebox Hits, many of them barely 2 and a half minutes long, and none more than 3 minutes. And how much time do you need anyway – when you’re the Wicked Pickett?

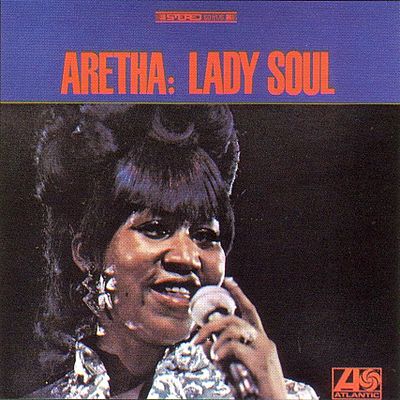

When Aretha Franklin recorded her first song, the brisk and bluesy “Maybe I’m a Fool” at the age of 18 in 1960, it was the beginning of a decade of superior-quality popular music from a young woman who quickly became one of the masterful song Interpreters of the 1960s. On Lady Soul, from 1967-68, Aretha sings two songs that show off her voice in different moods – and she gets ’em both exactly Right-ON. The telling-it-like-it-is“Chain of Fools” and Carole King’s “You Make Me Feel Like a Natural Woman” (Aretha’s version of this is the one.) The Lady Soul album included among the background vocalists Aretha’s sisters Carolyn and Emma, and Whitney Houston’s mother, Cissy.

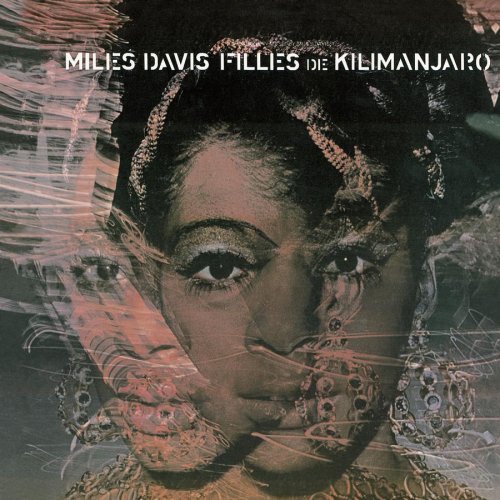

Miles Davis was making a transition from acoustic jazz to electric sounds when he recorded Filles de Kilamanjaro in 1968. Personnel included: Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock / Chick Corea, Ron Carter / Dave Holland, and Tony Williams. We far prefer this quirky album to the chilly perfection of Kind of Blue.

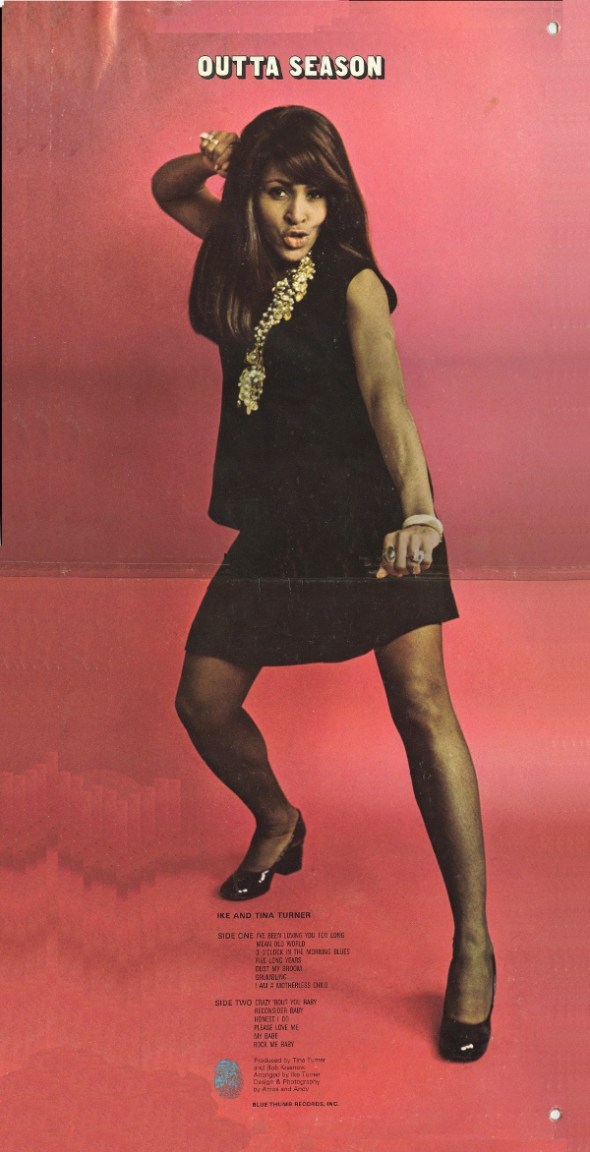

1969’s Outta Season! is all classic Blues from Ike and Tina Turner, with the addition of the old Spiritual “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child”. We agree with Nat Freedland’s appraisal of Tina Turner’s voice and presence from this period: “Tina is such a fine singer and such a superlative performer that any reaction less than adulation seems pointless.” (Billboard magazine, October 1971).

Roberta Flack & Donny Hathaway: In 1971-72 these two intensely-personal singers teamed up for an album that included soul, pop, and a powerful rendition of a 19th-century hymn, “Come, Ye Disconsolate”.

Al Green‘s 1972 album, I’m Still in Love with You: 35 minutes of exquisite Love Music. This was the Billboard chart #1 R.& B. album in December 1972, and Green’s pleading, confessional tone with a lyric makes you know why. Soul, Gospel, Pop, even a Country ‘feeling’ – all together as they rarely have been. “Love and Happiness”, “I’m Still in Love with You”, and “Look What You Done for Me” are standouts.

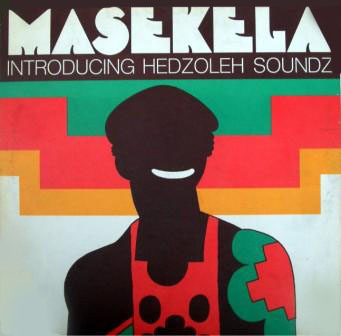

It’s hard to top Al Green’s album mentioned above – but Hedzoleh Soundz, an early 1970s combo. group from Ghana – with West African traditional and pop/rock musicians weaving into an Afro-Jazz sound – plus South African Hugh Masekela‘s trumpet sewing it all up – somehow DOES!

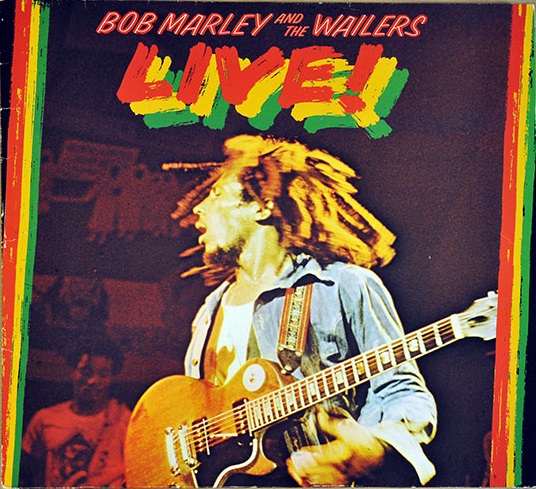

Bob Marley and The Wailers and the “I-Threes”, recorded live at The Lyceum in London, England, 1975. What can we say? The standard setter for great first-generation Reggae.

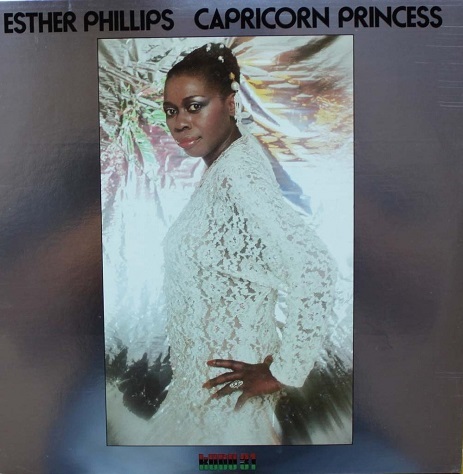

Esther Phillips has one of the best voices in recorded popular music – it may be too good, in fact. Her voice’s number 1 quality is Real-ness, and your ass’s been song’d by the time the needle leaves the groove. She was versatile, too – blues, jazz, country, pop – you name it, her voice held it all. Her 1972 version of Gil Scott-Heron’s “Home is Where the Hatred Is” is the definitive version of that disturbing drug-addiction cri-de-coeur (Phillips died at the age of 48, in 1984, after three decades of chronic hard-drug use.) If you can find a copy, listen to “All the Way Down” from the album pictured here, 1976’s Capricorn Princess.

Evelyn “Champagne” King‘s debut album, Smooth Talk, was released in 1977. The 18 year old had been cleaning offices and producer T. Life overheard her singing. He coached the teenager and in no time she delivered perhaps the single best Disco song ever – “Shame”. 6 minutes and 37 seconds long, it was a group effort, of course; there were real horns, plus guitar, bass, a drummer, keyboards, clavinet, organ, and a half a dozen judiciously-placed background vocalists. But King was a singer who could sing – her voice has a rawness and delicacy all at once – in other words, real character. It’s instructive to listen to a song like “Shame” nowadays and, if you’re old enough, you’ll remember when such mid-tempo dance songs were commonplace and that the bass beat was rarely punchy or mixed too big and too far forward. (Beware Remixes – such “pumped up” re-releases of quote-unquote Retro or Old-School dance numbers from a generation-or-more ago rob the songs of their integrity.) While many people made fun of Disco – even when it was “the trend” (approx.1976 – 1981) – it’s also true that too much of 21st-century Dance music (“Club” music) is pretty generic, features unmemorable voices, and requires a Video to make you believe you really Dig It. Are we showing our age here? Well, alright then.

Linda Clifford was given the full treatment for her 1979 Disco double-album, Let Me Be Your Woman: a cover portrait by Francesco Scavullo and an all-Woman centrefold (but classy!) when you flipped the jacket open. Clifford turns Simon and Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Water” into the funky disco anthem it should always have been, complete with “talking drums”. And “Don’t Give It Up” is 9 minutes of common-sense Rap – in its 1960s’ meaning: “keeping it real” and “having your say”. Clifford’s opening line: “Alright, Girls, come on now. We gonna have to git together and figure out what we gonna do with all these Men!”

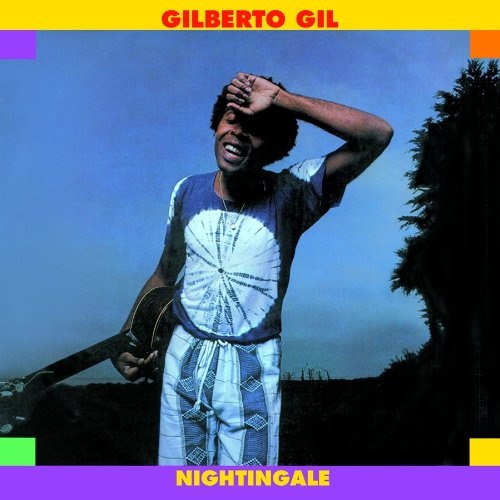

“Balafon” and “Maracatu Atômico” from 1979 are examples of sweet-voiced Gilberto Gil‘s playful melding of Afro-Brazilian themes and rhythms with pop music – something so typically Brazilian. Brazil has the most variety musically of all countries on the planet; its musical inventiveness and hybrid vigour are unparalleled.

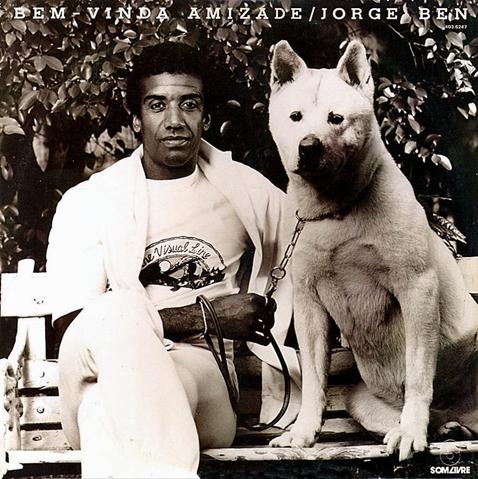

Jorge Ben, like his countryman Gilberto Gil, is restlessly creative on this 1981 album of Brazilian pop…

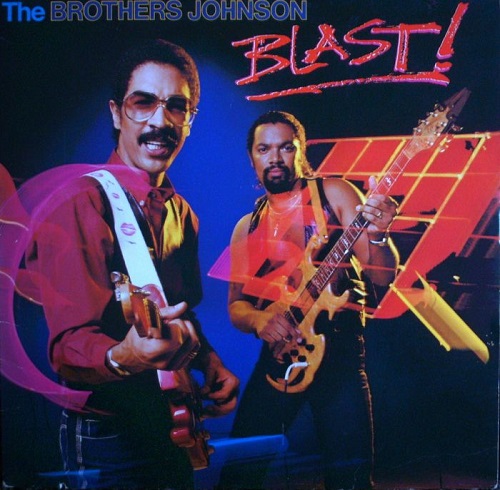

The Brothers Johnson‘s Blast! from 1982 contained the final great Disco track – “Stomp”. Yeah, it’s funky too, but make no mistake, this is Disco at its best, and a sexy, muscular last hurrah just as pop-music trends were veering off toward the self-conscious weirdness of New Wave.

The Pointer Sisters (Anita, June and Ruth) were a seasoned trio all in their thirties (fourth sister Bonnie struck out on her own in the late 1970s) by the time their 1983 album Break Out was released. Their strikingly-low alto voices combined with a synthesizer-dense instrumental made the song “Automatic” one of the quintessential 1980s tracks. The “12-inch” extended version of the song is an “Electro-Dance” classic of that decade. But it’s the Sisters’ rich, full vocals that really make the song.

. . . . .

“Make sparks”: an inspirational poem

Posted: February 4, 2014 Filed under: Alexander Best, English | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on “Make sparks”: an inspirational poem“Make sparks”: an inspirational poem

.

Best, Carrie;

Desmond, Viola;

Rosa Parks.

Two at The Movies;

One on The Bus;

Three for Justice.

.

Step upon step,

Day after day,

Choice by choice.

And what if You,

And what if I,

Lend our voices,

Look Wrong in its eye?

.

It’s hard to have guts

Yet do it we must

– no ifs, ands, or buts –

Cry “Freedom!” and Aye –

Trust in Our Common Future.

. . .

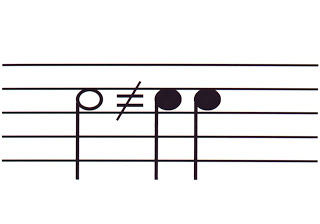

The illustration at the top is called “Poesía visual para Rosa Parks” by Rodrigo Alvarez. Alvarez uses musical symbols in ironic fashion. His equation means: one white half note does not equal two black quarter notes. Yet in musical notation half notes are white, and they do equal two black quarter notes. Alvarez has created a confusing “non-equation” to draw attention to untenable notions of racial segregation and inequality.

. . . . .