Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz: “Stupid, conceited Men…..” / “Hombres necios…..”

Posted: July 11, 2012 Filed under: English, Juana Inés de la Cruz, Spanish Comments Off on Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz: “Stupid, conceited Men…..” / “Hombres necios…..”

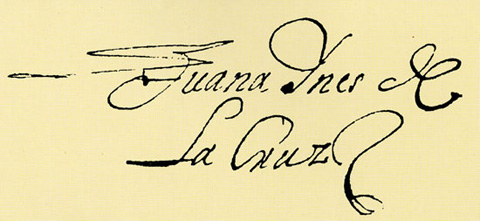

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

(1651-1695, Nueva España/México)

Hombres necios

Hombres necios que acusáis

a la mujer sin razón,

sin ver que sois la ocasión

de lo mismo que culpáis:

*

si con ansia sin igual

solicitáis su desdén,

¿por qué quereis que obren bien

si las incitáis al mal?

*

Combatís su resistencia

y luego, con gravedad,

decís que fue liviandad

lo que hizo la diligencia.

*

Parecer quiere el denuedo

de vuestro parecer loco,

al niño que pone el coco

y luego le tiene miedo.

*

Queréis, con presunción necia,

hallar a la que buscáis,

para pretendida, Thais,

y en la posesión, Lucrecia

*

¿Qué humor puede ser más raro

que el que, falto de consejo,

el mismo empaña el espejo

y siente que no esté claro?

*

Con el favor y el desdén

tenéis condición igual,

quejándoos, si os tratan mal,

burlándoos, si os quieren bien.

*

Opinión, ninguna gana:

pues la que más se recata,

si no os admite, es ingrata,

y si os admite, es liviana

*

Siempre tan necios andáis

que, con desigual nivel,

a una culpáis por crüel

y a otra por fácil culpáis.

*

¿Pues cómo ha de estar templada

la que vuestro amor pretende,

si la que es ingrata, ofende,

y la que es fácil, enfada?

*

Mas, entre el enfado y pena

que vuestro gusto refiere,

bien haya la que no os quiere

y quejaos en hora buena.

*

Dan vuestras amantes penas

a sus libertades alas,

y después de hacerlas malas

las queréis hallar muy buenas.

*

¿Cuál mayor culpa ha tenido

en una pasión errada:

la que cae de rogada

o el que ruega de caído?

*

¿O cuál es más de culpar,

aunque cualquiera mal haga:

la que peca por la paga

o el que paga por pecar?

*

Pues ¿para quée os espantáis

de la culpa que tenéis?

Queredlas cual las hacéis

o hacedlas cual las buscáis.

*

Dejad de solicitar,

y después, con más razón,

acusaréis la afición

de la que os fuere a rogar.

*

Bien con muchas armas fundo

que lidia vuestra arrogancia,

pues en promesa e instancia

juntáis diablo, carne y mundo.

_____

Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz

(1651-1695, New Spain/México)

Stupid, conceited men

Silly, you men – so very adept

at wrongly faulting womankind,

not seeing you’re alone to blame

for faults you plant in woman’s mind.

*

After you’ve won by urgent plea

the right to tarnish her good name,

you still expect her to behave–

you, that coaxed her into shame.

*

You batter her resistance down

and then, all righteousness, proclaim

that feminine frivolity,

not your persistence, is to blame.

*

When it comes to bravely posturing,

your witlessness must take the prize:

you’re the child that makes a bogeyman,

and then recoils in fear and cries.

*

Presumptuous beyond belief,

you’d have the woman you pursue

be Thais when you’re courting her,

Lucretia once she falls to you.

*

For plain default of common sense,

could any action be so queer

as oneself to cloud the mirror,

then complain that it’s not clear?

*

Whether you’re favored or disdained,

nothing can leave you satisfied.

You whimper if you’re turned away,

you sneer if you’ve been gratified.

*

With you, no woman can hope to score;

whichever way, she’s bound to lose;

spurning you, she’s ungrateful–

succumbing, you call her lewd.

*

Your folly is always the same:

you apply a single rule

to the one you accuse of looseness

and the one you brand as cruel.

*

What happy mean could there be

for the woman who catches your eye,

if, unresponsive, she offends,

yet whose complaisance you decry?

*

Still, whether it’s torment or anger–

and both ways you’ve yourselves to blame–

God bless the woman who won’t have you,

no matter how loud you complain.

*

It’s your persistent entreaties

that change her from timid to bold.

Having made her thereby naughty,

you would have her good as gold.

*

So where does the greater guilt lie

for a passion that should not be:

with the man who pleads out of baseness

or the woman debased by his plea?

*

Or which is more to be blamed–

though both will have cause for chagrin:

the woman who sins for money

or the man who pays money to sin?

*

So why are you men all so stunned

at the thought you’re all guilty alike?

Either like them for what you’ve made them

or make of them what you can like.

*

If you’d give up pursuing them,

you’d discover, without a doubt,

you’ve a stronger case to make

against those who seek you out.

*

I well know what powerful arms

you wield in pressing for evil:

your arrogance is allied

with the world, the flesh, and the devil.

Traducción del español al inglés / Translation from Spanish into English: Alan S. Trueblood

In his biography of Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz (1651-1695), Octavio Paz states that the self-taught scholar and nun of colonial New Spain (later called México) is the most important poet of the Americas up until the arrival of Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson in the 19th century. We must include the Aztec “poet-king” Nezahualcóyotl (1402-1472) in a statement so broad, yet de la Cruz does have something unique: a prototypical “feminist” point of view.

Juana Inés de la Cruz lived in México City from the age of 16 onward, and died during a plague at the age of 43 – after tending to the stricken. The out-of-wedlock daughter of a Spanish captain and a Criolla woman, she was an avid reader from childhood, and though she begged to disguise herself as a boy so as to continue her studies “more openly, in the Capital”, still she was “found out” and barred entrance to the university. That didn’t stop her – she kept on educating herself – and she’d already had a good head start, sneaking ( – in colonial society women were strongly discouraged from becoming literate in all but religious devotional texts – ) her grandfather’s books to read from his hacienda library. By her mid-teens she could speak and write in Latin, as well as Náhuatl, the language of the Aztecs. Devout and a “Daughter of The Church” though she was, yet she challenged male hypocrisy in the poem featured here, Hombres Necios/Stupid, conceited Men. Written in the conventional rhyming-quatrain verse form of the 17th century, Sister Juana addresses all Men; the poet analyzes their attraction to, and efforts to attain, women who will have sex with them — women whom the men reject and judge utterly, afterwards.