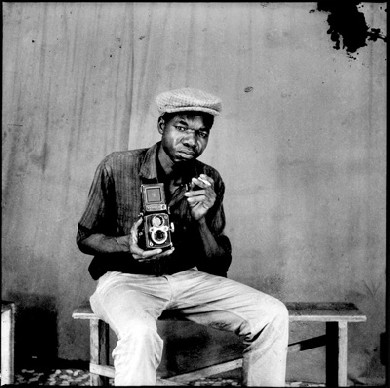

Jean Depara: chronicler of Kinshasa nightlife

Posted: February 16, 2016 Filed under: IMAGES | Tags: African photographers: Democratic Republic of the Congo, Black History Month Comments Off on Jean Depara: chronicler of Kinshasa nightlife. . .

Lemvo Jean Abou Bakar Depara

(born 1928, Angola – died 1997, Kinshasa, DRC)

.

Jean Depara became a photographer almost by accident. Wishing to document his wedding in 1950 he bought a small Adox camera— and after that he never lacked curiosity or fresh subject matter for his “eye”. He put down roots in Kinshasa in 1951, and at first combined part-time photography with a variety of other jobs: repairing bicycles and cameras, and dealing in scrap metal. In 1954 a Zairian singer invited him to become his official photographer, launching Depara’s career as a chronicler of Kinshasa social life in the decades when the dance music of rumba and cha-cha characterized the city’s “rhythm”. He set up a studio under the name Jean “Whisky” Depara, spending days and nights in the bars and nightclubs of Kinshasa: the Afro Mogenbo, the Champs-Elysées, the Djambo Djambu, the Oui, the Fifi, and the Show Boat. Intrigued as he was by the “night owl” crowd, Depara with his camera flash made a visual record of a Congo that existed outside of conventional social codes of the day.

.

Depara died leaving an archive of hundreds of untitled black and white negatives. With permission from the artist’s family, his friend Oscar Mbemba titled many of Depara’s photographs in the spirit of the bygone era.

. . . . .

Andre Bagoo: “I am the Archipelago”: Eric Roach and Black Identity

Posted: February 28, 2015 Filed under: 7 GUEST EDITORS, Andre Bagoo, English, Eric Merton Roach | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Andre Bagoo: “I am the Archipelago”: Eric Roach and Black Identity“I am the Archipelago”: Eric Roach and Black Identity

By Andre Bagoo

.

THOSE who know Eric Roach, know how the story ends. This year marks the centenary of the Trinidadian poet who was born in 1915 at Mount Pleasant, Tobago. He worked as a schoolteacher, civil servant and journalist, among other things. Along the way, he published in periodicals regularly. But in 1974, he wrote the poem ‘Finis’, drank insecticide, then swam out to sea at Quinam Bay. The first-ever collected edition of his poetry only appeared two decades after his death. In it, Ian McDonald describes Roach as, “one of the major West Indian poets”. He places Roach alongside Claude McKay, Derek Walcott, Louise Bennett, Martin Carter and Edward Kamau Brathwaite.

.

Too often is the discourse on Roach coloured by his story’s ending. We cannot ignore the facts of what occurred at Quinam Bay, yes, but sometimes they distract from the poet’s genuine achievements. Notwithstanding the emerging consensus on his stature, he is still best known for his ill-fated death. Yet the journey is sometimes more important than the destination.

.

In an introduction to the same collected edition of Roach’s poems published by Peepal Tree Press in 1992, critic Kenneth Ramchand states: “in the English-speaking Caribbean, is there anyone who had written as passionately about slavery and its devastations before ‘I am the Archipelago’ (1957) hit our colonised eardrums?” Ramchand notes that Roach was, “committed, as selflessly and as passionately as one can be, to the idea of a unique Caribbean civilisation taking shape out of the implosion of cultures and peoples in the region.” For Ramchand, “the ultimate justification of [Roach’s] art would be that it contributed to the making and understanding of this new, cross-cultural civilisation.” That cross-cultural civilisation is the one Walcott speaks of when he remarks:

.

Break a vase, and the love which reassembles the fragments is stronger than the love which took its symmetry for granted when it was whole….This gathering of broken pieces is the care and pain of the Antilles….Antillean art is this restoration of our shattered histories, our shards of vocabulary, our archipelago becoming a synonym for pieces broken off from the original continent.

.

This is really a call for the new breed of Caribbean poets, the breed that reverses colonialisation’s history of plunder. Just as our colonial overlords of the past have done, poets, now, are free to pillage from whichever continent they choose. This is not a process of retribution, but rather the restoration of the resilience of the human spirit itself amid the sea of history. It also asserts the reality of the fact that we are as much a part of world culture as anyone else and cannot be marginalised from it.

.

Roach – sometimes called the “Black Yeats”– was one in a long line of poets for whom imitation and allusion are, in fact, blatant acts of rebellion. He also saw himself as key to the process of forming a West Indian Federation, a political union which he felt required a new poetry. Though that union never came to pass, Roach’s work still serves to engage key aspects of Caribbean identity.

The narrative of Black identity, whatever that may be, has to some extent played on the idea of separate black and white races. It has also called for a rejection of “white” ideas and a return to African ideas. But these are uneasy dichotomies which paper over the realities of history over time, the mixing of races and the idea that race itself is an invention. At the same time, these categories ignore the complexity of colonisation. That process of colonisation saw states and peoples being exploited for economic resources and then, in the mid-20th century, abandoned by colonial motherlands under the pretence of liberation – even as strong economic subservience remains in place to this very day.

.

And this is why Roach remains relevant: he not only asserts that the English language is as much ours as theirs, but also sings of the true implications of history, a history sometimes obscured by neat narratives of “independence” and “emancipation”. This is why Roach is still alive.

. . .

I AM THE ARCHIPELAGO

.

I am the archipelago hope

Would mould into dominion; each hot green island

Buffeted, broken by the press of tides

And all the tales come mocking me

Out of the slave plantations where I grubbed

Yam and cane; where heat and hate sprawled down

Among the cane – my sister sired without

Love or law. In that gross bed was bred

The third estate of colour. And now

My language, history and my names are dead

And buried with my tribal soul. And now

I drown in the groundswell of poverty

No love will quell. I am the shanty town,

Banana, sugarcane and cotton man;

Economies are soldered with my sweat

Here, everywhere; in hate’s dominion;

In Congo, Kenya, in free, unfree America.

.

I herd in my divided skin

Under a monomaniac sullen sun

Disnomia deep in artery and marrow.

I burn the tropic texture from my hair;

Marry the mongrel woman or the white;

Let my black spinster sisters tend the church,

Earn meagre wages, mate illegally,

Breed secret bastards, murder them in womb;

Their fate is written in unwritten law,

The vogue of colour hardened into custom

In the tradition of the slave plantation.

The cock, the totem of his craft, his luck,

The obeahman infects me to my heart

Although I wear my Jesus on my breast

And burn a holy candle for my saint.

I am a shaker and a shouter and a myal man;

My voodoo passion swings sweet chariots low.

.

My manhood died on the imperial wheels

That bound and ground too many generations;

From pain and terror and ignominy

I cower in the island of my skin,

The hot unhappy jungle of my spirit

Broken by my haunting foe my fear,

The jackal after centuries of subjection.

But now the intellect must outrun time

Out of my lost, through all man’s future years,

Challenging Atalanta for my life,

To die or live a man in history,

My totem also on the human earth.

O drummers, fall to silence in my blood

You thrum against the moon; break up the rhetoric

Of these poems I must speak. O seas,

O Trades, drive wrath from destinations.

.

(1957)

. . .

Andre Bagoo is a Trinidadian poet and journalist, born in 1983. His second book of poems, BURN, is published by Shearsman Books. To read more ZP features by Andre Bagoo, click on his name under “Guest Editors” in the right-hand column.

. . . . .

Jackie Ormes: Torchy, Candy, Patty-Jo & Ginger!

Posted: February 28, 2015 Filed under: English | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Jackie Ormes: Torchy, Candy, Patty-Jo & Ginger!

Jackie Ormes (1911-1985), considered to be the first Black-American Woman cartoonist /syndicated comic-strip writer/illustrator, was born Zelda Mavin Jackson in Monongahela, Pennysylvania, just outside of Pittsburgh. She began her newspaper career as a proofreader for the Pittsburgh Courier, an African-American weekly that appeared every Saturday. .

Nancy Goldstein, author of an exceptionally-detailed 2008 biography of Ormes, states:

“In the United States at mid (20th) century – a time of few opportunities for women in general and even fewer for African-American women – Jackie Ormes blazed a trail as a popular cartoonist with the major Black newspapers of the day.” Her cartoon characters Torchy Brown (1937-38, 1950-54), Candy (1945), and the memorable duo of Patty-Jo and Ginger (Ginger a glamorous quasi-“pin-up” girl, and Patty-Jo her frank and accurate kid sister, 1945-56) delighted readers of the Pittsburgh Courier and the Chicago Defender.

“Torchy Brown in Dixie to Harlem” was a comic-strip telling the tale of a Mississippi teenager who finds fame and fortune as a singer and dancer at The Cotton Club. “Candy”, a single-panel comic, featured a wise-cracking housemaid. In the 11-year-running “Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger”, precocious child Patty-Jo “kept it real” (as only a child could) in her commentaries about a range of topics – racial segregation, U.S. Foreign policy, education reform, the atom bomb, McCarthy’s “Red” paranoia, etc., while her older “Sis”, Ginger, posed or strutted in mute mannequin glamour. Both Ginger, and the later Torchy Brown (of Torchy Brown in “Heartbeats”) presented gorgeous and fashionable Black women in an era when few such images were to be found. The final newspaper strip for “Heartbeats” in 1954 also hit home on themes of racism and environmental pollution.

Briefly, from 1947-1949, Ormes was contracted by a doll company to design a realistic Black girl doll (not a Mammy or Topsy stereotype), and she would become an avid doll collector in later life. Married happily for four and a half decades, she retired from cartooning in 1956 but continued to draw and paint still-lifes, portraits and murals. One of the founding directors of the DuSable Museum of African-American History in Chicago, she was deeply committed to her community.

But it is Jackie Ormes’ special populist-art contribution to American culture – her unique comics – that we remember today – during Black History Month 2015!

Teju Cole on photographer Roy DeCarava: A True Picture of Black Skin

Posted: February 23, 2015 Filed under: English | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Teju Cole on photographer Roy DeCarava: A True Picture of Black SkinTeju Cole on photographer Roy DeCarava: A True Picture of Black Skin

(reprinted from The New York Times Magazine, February 18th, 2015)

.

What comes to mind when we think of photography and the civil rights movement? Direct, viscerally affecting images with familiar subjects: huge rallies, impassioned speakers, people carrying placards (“I Am a Man”), dogs and fire hoses turned on innocent protesters. These photos, as well as the portraits of national leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, are explicit about the subject at hand. They tell us what is happening and make a case for why things must change. Our present moment – 2015 – a time of vigorous demand for equal treatment, evokes those years of sadness and hope in Black American life and renews the relevance of those photos.

But there are other, less expected images from the civil rights years that are also worth thinking about: images that are forceful but less illustrative.

One such image left me short of breath the first time I saw it.

It’s of a young woman whose face is at once relaxed and intense. She is apparently in bright sunshine, but both her face and the rest of the picture give off a feeling of modulated darkness; we can see her beautiful features, but they are underlit somehow. Only later did I learn the picture’s title, “Mississippi Freedom Marcher, Washington, D.C., 1963” which helps explain the young woman’s serene and resolute expression. It is an expression suitable for the event she’s attending, the most famous civil rights march of them all. The title also confirms the sense that she’s standing in a great crowd, even though we see only half of one other person’s face (a boy’s, indistinct in the foreground) and, behind the young woman, the barest suggestion of two other bodies.

The picture was taken by Roy DeCarava (1919-2009), one of the most intriguing and poetic of American photographers. The power of this picture is in the loveliness of its dark areas. His work was, in fact, an exploration of just how much could be seen in the shadowed parts of a photograph, or how much could be imagined into those shadows. He resisted being too explicit in his work, a reticence that expresses itself in his choice of subjects as well as in the way he presented them.

.

DeCarava, a lifelong New Yorker, came of age in the generation after the Harlem Renaissance and took part in a flowering in the visual arts that followed that largely literary movement. By the time he died in 2009, at 89, he was celebrated for his melancholy and understated scenes, most of which were shot in New York City: streets, subways, jazz clubs, the interiors of houses, the people who lived in them. His pictures all share a visual grammar of decorous mystery: a woman in a bridal gown in the empty valley of a lot, a pair of silhouetted dancers reading each other’s bodies in a cavernous hall, a solitary hand and its cuff-linked wrist emerging from the midday gloom of a taxi window. DeCarava took photographs of white people tenderly but seldom. Black life was his greater love and steadier commitment. With his camera he tried to think through the peculiar challenge of shooting black subjects at a time when black appearance, in both senses (the way black people looked and the very presence of black people), was under question.

.

All technology arises out of specific social circumstances. In our time, as in previous generations, cameras and the mechanical tools of photography have rarely made it easy to photograph black skin. The dynamic range of film emulsions, for example, were generally calibrated for white skin and had limited sensitivity to brown, red or yellow skin tones. Light meters had similar limitations, with a tendency to underexpose dark skin. And for many years, beginning in the mid-1940s, the smaller film-developing units manufactured by Kodak came with Shirley cards, so-named after the white model who was featured on them and whose whiteness was marked on the cards as “normal.” Some of these instruments improved with time. In the age of digital photography, for instance, Shirley cards are hardly used anymore. But even now, there are reminders that photographic technology is neither value-free nor ethnically neutral. In 2009, the face-recognition technology on HP webcams had difficulty recognizing black faces, suggesting, again, that the process of calibration had favored lighter skin.

An artist tries to elicit from unfriendly tools the best they can manage. A black photographer of black skin can adjust his or her light meters; or make the necessary exposure compensations while shooting; or correct the image at the printing stage. These small adjustments would have been necessary for most photographers who worked with black subjects, from James Van Der Zee at the beginning of the century to DeCarava’s best-known contemporary, Gordon Parks, who was on the staff of Life magazine. Parks’s work, like DeCarava’s, was concerned with human dignity, specifically as it was expressed in black communities. Unlike DeCarava, and like most other photographers, he aimed for and achieved a certain clarity and technical finish in his photo essays. The highlights were high, the shadows were dark, the mid-tones well-judged. This was work without exaggeration; perhaps for this reason it sometimes lacked a smoldering fire even though it was never less than soulful.

DeCarava, on the other hand, insisted on finding a way into the inner life of his scenes. He worked without assistants and did his own developing, and almost all his work bore the mark of his idiosyncrasies. The chiaroscuro effects came from technical choices: a combination of underexposure, darkroom virtuosity and occasionally printing on soft paper. And yet there’s also a sense that he gave the pictures what they wanted, instead of imposing an agenda on them. In “Mississippi Freedom Marcher,” for example, even the whites of the shirts have been pulled down, into a range of soft, dreamy grays, so that the tonalities of the photograph agree with the young woman’s strong, quiet expression. This exploration of the possibilities of dark gray would be interesting in any photographer, but DeCarava did it time and again specifically as a photographer of black skin. Instead of trying to brighten blackness, he went against expectation and darkened it further. What is dark is neither blank nor empty. It is in fact full of wise light which, with patient seeing, can open out into glories.

This confidence in “playing in the dark” (to borrow a phrase of Toni Morrison’s) intensified the emotional content of DeCarava’s pictures. The viewer’s eye might at first protest, seeking more conventional contrasts, wanting more obvious lighting. But, gradually, there comes an acceptance of the photograph and its subtle implications: that there’s more there than we might think at first glance, but also that when we are looking at others, we might come to the understanding that they don’t have to give themselves up to us. They are allowed to stay in the shadows if they wish.

.

Thinking about DeCarava’s work in this way reminds me of the philosopher Édouard Glissant, who was born in Martinique, educated at the Sorbonne and profoundly involved in anticolonial movements of the ’50s and ’60s. One of Glissant’s main projects was an exploration of the word “opacity.” Glissant defined it as a right to not have to be understood on others’ terms, a right to be misunderstood if need be. The argument was rooted in linguistic considerations: It was a stance against certain expectations of transparency embedded in the French language. Glissant sought to defend the opacity, obscurity and inscrutability of Caribbean blacks and other marginalized peoples. External pressures insisted on everything being illuminated, simplified and explained. Glissant’s response: No. And this gentle refusal, this suggestion that there is another way, a deeper way, holds true for DeCarava, too.

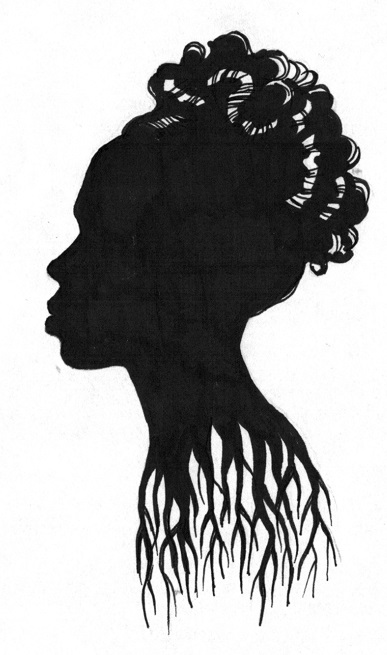

DeCarava’s thoughtfulness and grace influenced a whole generation of black photographers, though few of them went on to work as consistently in the shadows as he did. But when I see luxuriantly crepuscular images like Eli Reed’s photograph of the Boys’ Choir of Tallahassee (2004), or those in Carrie Mae Weems’s “Kitchen Table Series” (1990), I see them as extensions of the DeCarava line. One of the most gifted cinematographers currently at work, Bradford Young, seems to have inherited DeCarava’s approach even more directly. Young shot Dee Rees’s “Pariah” (2011) and Andrew Dosunmu’s “Restless City” (2012) and “Mother of George” (2013), as well as Ava DuVernay’s “Selma” (2014). He works in color, and with moving rather than still images, but his visual language is cognate with DeCarava’s: Both are keeping faith with the power of shadows.

The leading actors in the films Young has shot are not only black but also tend to be dark-skinned: Danai Gurira as Adenike in “Mother of George,” for instance, and David Oyelowo as Martin Luther King Jr., in “Selma.” Under Young’s lenses, they become darker yet and serve as the brooding centers of these overwhelmingly beautiful films. Black skin, full of unexpected gradations of blue, purple or ocher, set a tone for the narrative: Adenike lost in thought on her wedding day, King on an evening telephone call to his wife or in discussion in a jail cell with other civil rights leaders. In a larger culture that tends to value black people for their abilities to jump, dance or otherwise entertain, these moments of inwardness open up a different space of encounter.

These images pose a challenge to another bias in mainstream culture: that to make something darker is to make it more dubious. There have been instances when a black face was darkened on the cover of a magazine or in a political ad to cast a literal pall of suspicion over it, just as there have been times when a black face was lightened after a photo shoot with the apparent goal of making it more appealing. What could a response to this form of contempt look like? One answer is in Young’s films, in which an intensified darkness makes the actors seem more private, more self-contained and at the same time more dramatic. In “Selma,” the effect is strengthened by the many scenes in which King and the other protagonists are filmed from behind or turned away from us. We are tuned into the eloquence of shoulders, and we hear what the hint of a profile or the fragment of a silhouette has to say.

I think of another photograph by Roy DeCarava that is similar to “Mississippi Freedom Marcher,” but this other photograph, “Five Men, 1964,” has quite a different mood. We see one man, on the left, who faces forward and takes up almost half the picture plane. His face is sober and tense, his expression that of someone whose mind is elsewhere. Behind him is a man in glasses. This second man’s face is in three-quarter profile and almost wholly visible except for where the first man’s shoulder covers his chin and jawline. Behind these are two others, whose faces are more than half concealed by the men in front of them. And finally there’s a small segment of a head at the bottom right of the photograph. The men’s varying heights could mean they are standing on steps. The heads are close together, and none seem to look in the same direction: The effect is like a sheet of studies made by a Renaissance master. In an interview DeCarava gave in 1990 in the magazine Callaloo, he said of this picture: “This moment occurred during a memorial service for the children killed in a church in Birmingham, Ala., in 1964. The photograph shows men coming out of the service at a church in Harlem.” He went on to say that the “men were coming out of the church with faces so serious and so intense that I responded, and the image was made.”

The adjectives that trail the work of DeCarava and Young as well as the philosophy of Glissant — opaque, dark, shadowed, obscure — are metaphorical when we apply them to language. But in photography, they are literal, and only after they are seen as physical facts do they become metaphorical again, visual stories about the hard-won, worth-keeping reticence of black life itself. These pictures make a case for how indirect images guarantee our sense of the human. It is as if the world, in its careless way, had been saying, “You people are simply too dark,” and these artists, intent on obliterating this absurd way of thinking, had quietly responded, “But you have no idea how dark we yet may be, nor what that darkness may contain.”

. . .

Teju Cole is a Nigerian-American writer whose two works of fiction, Open City and Every Day Is for the Thief, have been critically acclaimed and awarded several prizes, including the PEN/Hemingway Award. He is distinguished writer in residence at Bard College and the NYT magazine’s photography critic. A writer, art historian, and photographer, he was born in the US in 1975 to Nigerian parents, and raised in Nigeria. He currently lives in Brooklyn.

. . .

African photographers featured at ZP:

https://zocalopoets.com/2013/06/29/zwelethu-mthethwa-zanele-muholi-rotimi-fani-kayode-samuel-fosso-african-photographers-who-make-you-think/

. . . . .

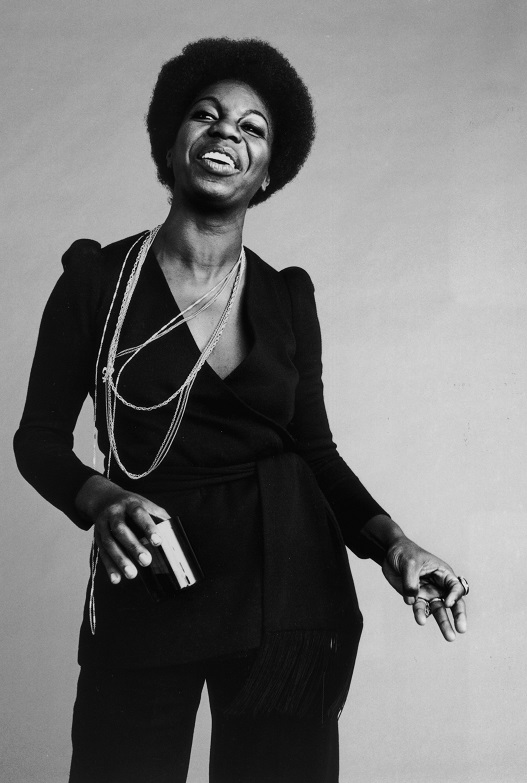

Great Women Jazz Singers: Nina Simone y su Hombre-Pecador

Posted: February 23, 2015 Filed under: English, Spanish | Tags: Black History Month, The Nina Project 2015 Comments Off on Great Women Jazz Singers: Nina Simone y su Hombre-PecadorUna canción firma-distintiva de Nina Simone…

Hombre-Pecador

(Letra: tradicional afroamericana, primeros años del siglo XX)

.

Ah, hombre-pecador, ¿adónde vas a escaparte?

Hombre-pecador, ¿adónde te fugas?

¿Adónde corres?

Todo en ese día.

.

Pues, corro a la peña – (escóndeme, te lo ruego.)

Sí, corro a la peña – (ay, escóndeme.)

Correré a esa peña – (Señor, escóndeme, por favor.)

Todo en ese día.

.

Pero, exclamó la peña: ¡no puedo esconderte!

La peña exclamó: ¡ah, no puedo esconderte!

Y la peña gritó: ¡no voy a esconderte, cuate!

Y pasará Todo – en Ese Día.

.

Dije:

¿Peña, qué te pasa?

¿No puedes ver que te necesito, mi Peña?

Señor, ay Señor,

Todo en ese día.

.

Pues, corrí al río – y estuvo sangrando.

Y corrí al mar – también estuvo sangrando

Ah sí, estuvo sangrando:

Y Todo pasó en ese día.

.

Pues el río, el mar – estuvieron hirviendo

Huí a los dos, pero ellos solo hirvieron.

Sí, huí a las aguas – y solo hirvieron

– y es lo que pasó en ese día.

.

Entonces, apuré al Señor y le rogué:

Escóndeme, por favor, te pido, Señor,

¿no me ves rozando, aquí abajo?

.

Pero Nuestro Señor me dijo:

¡Vete al Diablo!

(Sí, que yo debería irme al demonio…)

Vete al Diablo, Mi Señor me dijo,

Todo eso – en ese día.

.

Pues, fui derecho al Diablo

Y estuvo esperando.

Corré al Malo

– esperando para mí.

Sí, supo que llegué, y

Todo pasó en Ese Gran Día

.

Grito:

Poder, fuerza, energía…

Poder, fuerza, energía…

Gran poder con fuerza y energía…

– ¡Señor, métele!

Y digo:

Señor, ayúdame,

escóndeme, ayúdame.

Señor, escóndeme,

ayúdame, ayúdame…

Digo ésto, en este gran Día.

Y Él me dice:

Niño, ¿dónde estabas?

Quiero oír tu rezo.

Le digo:

¿Puedes oír mi rezo?

¡Oye mi rezo!

Estoy diciendo Todo – Todo durante El Gran Dia.

.

Poder, fuerza, energía

Poder, fuerza, energía

Poder, fuerza, energía

– Señor, ¡métele bien duro

sobre mi alma!

.

Poder poder poder poder…

¿No entiendes que te falto, Señor?

Oh sí, Señor, extraño a Tí,

Ah sí, Señor,

Ah sí.

. . .

The Nina Project highlights three award-winning, internationally-acclaimed African-Canadian vocalists – Jackie Richardson, Kellylee Evans and Shakura S’Aida – performing the music & lyrics of Nina Simone, (who would’ve turned 82 on February 21st, 2015.)

Few jazz vocalists have remained as relevant across the generations as Nina Simone. Her music is still played in its original form, and in dance/house tracks, plus everything in between!

What happens when three top-ranked vocalists, whose combined musical experience equals ninety-five years on stage, share their interpretation of Nina Simone?

Answer: The Nina Project!

Simone’s influence shows through their diverse performances…

Evans recently won a Juno for her Nina tribute album,

S’Aida performed a Simone tribute to a sold out audience, while

Richardson’s repertoire has included her favourite Nina songs for years.

Through three generations of Canadian Black entertainers,

The Nina Project shows how timeless, classic and sophisticated Simone was,

and how strongly her music prevails!

.

The Nina Project

February 23rd 2015 at the National Arts Centre, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

(through Black Artists’ Networks in Dialogue)

.

Cantante canadiense Kellylee Evans con su versión de Hombre-Pecado:

http://youtu.be/NIrxMbVVrCY

. . .

Sinner Man

(20th-century African-American Traditional / Spiritual)

.

Oh sinner man, where you gonna run to?

Sinner man, where you gonna run to?

Where you gonna run to?

All on that day.

Well I run to the rock

Please hide me,

I run to the rock

Please hide me,

I run to the rock

Please hide me, Lord,

All on that day.

But the rock cried out

“I can’t hide you”

the rock cried out

“I can’t hide you”

the rock cried out

“I ain’t gonna hide you, guy,

All on that day.

I said, “Rock what’s the matter with you, rock?

Don’t you see I need you, rock?”

Lord, Lord, Lord

All on that day.

So I run to the river

It was bleedin’,

I run to the sea

It was bleedin’,

I run to the sea

It was bleedin’

All on that day.

So I run to the river, it was boilin’

I run to the sea, it was boilin’

I run to the sea, it was boilin’

All on that day.

So I run to the Lord

“Please hide me, Lord,

Don’t you see me prayin’ ?

Don’t you see me down here prayin’ ?”

But the Lord said, “Go to the Devil”

The Lord said, “Go to the Devil”

He said, “Go to the Devil”

All on that day.

So I ran to the Devil

He was waitin’

I ran to the Devil, he was waitin’

I ran to the Devil, he was waitin’

All on that day.

I cried, “Power, power

Power, power, power

Power, power, power…

Bring it down

Bring it down!

Power, power, power

Power, power, power

Power, power, power

Power, power, power

Power, power, power…

Oh yeah, oh yeah, oh yeah!

Oh, I run to the river

It was boilin’, I run to the sea

It was boilin’, I run to the sea

It was boilin’

All on that day.

So I ran to the Lord

I said, Lord hide me

Please hide me

Please help me,

All on that day.

He said, “Child, where were you?

When you are old and prayin'”

Said, “Lord lord, hear me prayin’

Lord Lord, hear me prayin’

Lord Lord, hear me prayin’ ”

All on that day.

Sinner man, you oughta be prayin’

Oughta be prayin’, sinner man

Oughta be prayin’

All on that day.

I cried, Power, power

Power, power, power

Power, power, power

Power, power, power

Power, power, power…

Bring it down

All down

All down!

Bring it down

Power, power, power

Power, power, Lord!

Don’t you know?

Don’t you know I need you Lord?

Don’t you know when I need you?

Don’t you know, ho ho ho, that I need you?

Power, power, power, Lord!!!

Nina Simone sang a 10-minute version of “Sinner Man” on her album Pastel Blues, recorded in 1965…

. . . . .

Great Women Jazz Singers: Nancy Wilson, “Estilista” de Jazz

Posted: February 23, 2015 Filed under: Spanish | Tags: Black History Month, El Mes de la Historia Afroamericana Comments Off on Great Women Jazz Singers: Nancy Wilson, “Estilista” de JazzNancy Wilson: Estilista de la canción jazz: (n. 20 febrero 1937, Chillicothe, Ohio, EE.UU.)

.

La canción “firma distintiva” de su juventud…

En la Calle del Delfín Verde (compuesto en 1947):

(Música de Bronislaw Kaper, letras de Ned Washington)

.

¡Fue un bonito día, Cariño, cuando llegó el Amor

con la intención de quedarse!

La Calle del Delfín Verde proveyó el marco –

el marco de unas noches inolvidables…

.

Y, a través de estos momentos separados,

Se arraiga las memorias de Amor, aquí en mi corazón.

Cuando recuerdo el amor que descubrí,

puedo besar el suelo en la Calle del Delfín Verde!

. . .

Nancy Wilson cantando con el Quinteto de George Shearing (1961):

. . .

Letras en inglés:

On Green Dolphin Street

.

Lover, one lovely day

Love came planning to stay!

Green Dolphin Street supplied the setting,

The setting for nights beyond forgetting…

And, through these moments apart,

Memories live here in my heart!

When I recall the love I found

I could kiss the ground on Green Dolphin Street!

. . . . .

Great Women Jazz Instrumentalists + “Jazz” poems by Langston Hughes and Jayne Cortez

Posted: February 18, 2015 Filed under: English, Jayne Cortez, Langston Hughes | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Great Women Jazz Instrumentalists + “Jazz” poems by Langston Hughes and Jayne CortezLangston Hughes (1902-1967)

Juke Box Love Song

.

I could take the Harlem night

and wrap around you,

Take the neon lights and make a crown,

Take the Lenox Avenue buses,

Taxis, subways;

And for your love song tone their rumble down.

Take Harlem’s heartbeat,

Make a drumbeat,

Put it on a record, let it whirl;

And while we listen to it play,

Dance with you till day…

Dance with you, my sweet brown Harlem girl.

Langston Hughes

Life is Fine

.

I went down to the river,

I set down on the bank.

I tried to think but couldn’t,

So I jumped in and sank.

I came up once and hollered!

I came up twice and cried!

If that water hadn’t a-been so cold

I might’ve sunk and died.

But it was Cold in that water! It was cold!

.

I took the elevator

Sixteen floors above the ground.

I thought about my baby

And thought I would jump down.

.

I stood there and I hollered!

I stood there and I cried!

If it hadn’t a-been so high

I might’ve jumped and died.

But it was High up there! It was high!

.

So since I’m still here livin’,

I guess I will live on.

I could’ve died for love–

But for livin’ I was born

.

Though you may hear me holler,

And you may see me cry–

I’ll be dogged, sweet baby,

If you gonna see me die.

Life is fine! Fine as wine! Life is fine!

. . .

Langston Hughes

Dream Variations

.

To fling my arms wide

In some place of the sun,

To whirl and to dance

Till the white day is done.

Then rest at cool evening

Beneath a tall tree

While night comes on gently,

Dark like me:

That is my dream!

.

To fling my arms wide

In the face of the sun,

Dance! Whirl! Whirl!

Till the quick day is done.

Rest at pale evening,

A tall, slim tree,

Night coming tenderly –

Black like me.

Jayne Cortez (born Sallie Jayne Richardson, 1934-2012)

I am New York City

.

i am new york city

here is my brain of hot sauce

my tobacco teeth my

mattress of bedbug tongue

legs aparthand on chin

war on the roofinsults

pointed fingerspushcarts

my contraceptives all

look at my pelvis blushing

.

i am new york city of blood

police and fried pies

i rub my docks red with grenadine

and jelly madness in a flow of tokay

my huge skull of pigeons

my seance of peeping toms

my plaited ovaries excuse me

this is my grime my thigh of

steelspoons and toothpicks

i imitate no one

.

i am new york city

of the brown spit and soft tomatoes

give me my confetti of flesh

my marquee of false nipples

my sideshow of open beaks

in my nose of soot

in my ox bled eyes

in my ear of Saturday night specials

.

i eat ha ha hee hee and ho ho

i am new york city

never change never sleep never melt

my shoes are incognito

cadavers grow from my goatee

look i sparkle with shit with wishbones

my nickname is glue-me

.

take my face of stink bombs

my star spangled banner of hot dogs

take my beer can junta

my reptilian ass of footprints

and approach me through life

approach me through death

approach me through my widow’s peak

through my split ends my

asthmatic laughapproach me

through my wash rag

half anklehalf elbow

massage me with your camphor tears

salute the patina and concrete

of my rat tail wig

face upface downpiss

into the bite of our handshake

.

i am new york city

my skillet-head friend

my fat-bellied comrade

citizens

break wind with me

Jayne Cortez

Make Ifa

.

MAKE IFA MAKE IFA MAKE IFA IFA IFA

In sanctified chalk

of my silver painted soot

In criss-crossing whelps

of my black belching smoke

In brass masking bones

of my bass droning moans

in hub cap bellow

of my hammer tap blow

In steel stance screech

of my zumbified flames

In electrified mouth

of my citified fumes

In bellified groan

of my countrified pound

In compulsivefied conga

of my soca moka jumbi

MAKE IFA MAKE IFA MAKE IFA IFA IFA

In eye popping punta

of my heat sucking sap

In cyclonic slobber

of my consultation pan

In snap jam combustion

of my banjoistic thumb

In sparkola flare

of my hoodoristic scream

In punched out ijuba

of my fire catching groove

In fungified funk

of my sambafied shakes

In amplified dents

of my petrified honks

In ping ponging bombs

of my scarified gongs

MAKE IFA MAKE IFA MAKE IFA IFA IFA

. . .

Editor’s Note: Ifa = a system of divination developed by the Yoruba of

Nigeria, based on the interpretation of cowrie shells tossed on a tray.

. . . . .

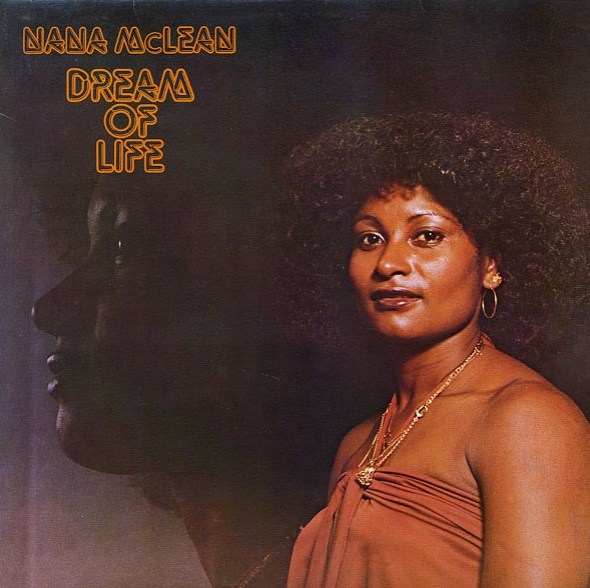

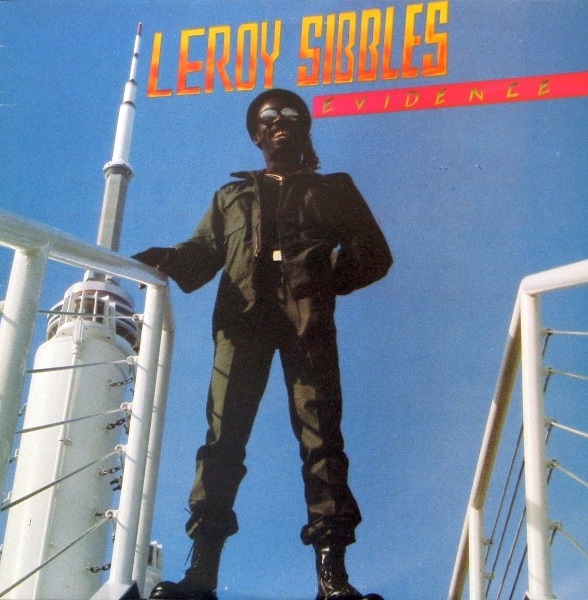

Toronto Reggae History Project: 1972-1987

Posted: February 10, 2015 Filed under: IMAGES | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Toronto Reggae History Project: 1972-1987 Visit Reggae Toronto at

Visit Reggae Toronto at

http://reggaetoronto.com/

Cumpleaños de Bob Marley: “400 años” y “Tontos tercos”

Posted: February 6, 2015 Filed under: Bob Marley, English, Spanish | Tags: Black History Month, El Mes de la Historia Afroamericana Comments Off on Cumpleaños de Bob Marley: “400 años” y “Tontos tercos”400 años, una canción de Peter Tosh, del album “Catch a Fire” (“Coge un Fuego”), grabado en 1973 por Bob Marley & The Wailers (“Los Plañideros”):

. . .

400 years, 400 years, 400 years…Wo-o-o-o,

And it’s the same philosophy.

I’ve said it’s four hundred years, 400 years, 400 years…Wo-o-o-o,

Look, how long!

And the people they still can’t see.

Why do they fight against the poor youth of today?

And without these youths, they would be gone, all gone astray.

.

Come on, let’s make a move, make a move, make a move…Wo-o-o-o,

I can see time, the time has come.

And if a-fools don’t see, fools don’t see, fools don’t see…Wo-o-o-o,

I can’t save the youth.

But the youth is gonna be strong!

So, won’t you come with me?

I’ll take you to a land of liberty

Where we can live – yes, live a good, good life,

And be free.

.

Look how long! (400 years, 400 years, 400 years…)

Way too long! (Wo-o-o-o…)

That’s the reason my people, my people can’t see.

Said: it’s four hundred long years (400 years, 400 years. Wo-o-o-o)

Give me patience – and it’s the same philosophy.

.

It’s been 400 years, 400 years, 400 years…

Wait so long! Wo-o-o-o,

How long?

400 long, long years…

. . .

400 años, 400 años, y seguimos teniendo la misma filosofía…

Yo he dicho que es 400 años, 400 años, y todavía la gente no ve más allá…

¿Por qué luchar contra los pobres jóvenes de hoy?

Sin ellos hoy estarían todos yendo por el mal camino…

Vamos, movámonos, la hora ha llegado, y aunque los tontos no lo ven como salvar a la juventud – pero ellos son fuertes…

Entonces, ¿por qué no vienes conmigo? Te llevaré a un lugar – la tierra de la libertad – donde podremos vivir bien y ser libres…

Mira – tan largo – 400 años, 400 años, tanto tiempo que no pueden ver más allá…

400 años, 400 años…Dame paciencia…la misma filosofía…

Hemos atravesado 400 años – hemos esperado tanto tiempo…largos años…

. . .

La frase 400 años hace referencia al principio del comercio de la esclavitud africana (durante el siglo XVI.) El primero ingenio azucarero jamaicano fue fundado en Sevilla La Nueva (cerca de Bahía Santa Ana) por los Españoles durante su periodo colonizador (1509–1655) en “Santiago” (el primero nombre castellano para Jamaica). En hecho, es la mayoría de Jamaicanos que son descendientes de esos esclavos…

Para leer otras letras de Bob Marley & The Wailers que se tratan de liberarse de las formas diversas de la esclavitud, cliquea en el enlace:

https://zocalopoets.com/2013/02/06/mind-is-your-only-ruler-sovereign-marcus-garvey-and-bob-marley-emancipense-de-la-esclavitud-mental-nadie-mas-que-nosotros-puede-liberar-nuestras-mentes/

. . . . .

Stiff-necked Fools (1980/1983)

.

Stiff-necked fools, you think you are cool

To deny me for simplicity.

Yes, you have gone for so long

With your love for vanity now.

Yes, you have got the wrong interpretation

Mixed up with vain imagination.

.

So take Jah Sun, and Jah Moon,

And Jah Rain, and Jah Stars,

And forever, yes, erase your fantasy, yeah!

.

The lips of the righteous teach many,

But fools die for want of wisdom.

The rich man’s wealth is in his city;

The righteous’ wealth is in his Holy Place.

So take Jah Sun, and Jah Moon,

And Jah Rain, and Jah Stars,

And forever, yes, erase your fantasy, yeah!

Destruction of the poor is in their poverty;

Destruction of the soul is vanity, yeah!

.

So stiff-necked fools, you think you are cool

To deny me for simplicity, yeah!

Yes, you have gone, gone for so long

With your love for vanity now.

.

But I don’t wanna rule ya!

I don’t wanna fool ya!

I don’t wanna school ya,

Things you might never know about!

.

Yes, you have got the wrong interpretation

Mixed up with vain imagination…

Stiff-necked fools, you think you are cool

To deny me for, ooh-ooh, simplicity!

. . .

Stiff-necked Fools: Marley has used phrases from The Bible in this song, particularly Proverbs 10, verses 15 and 21.

The Battle of Adwa fought in 1896 was the climactic confrontation of the First Italo-Ethiopian War, and it secured Ethiopian sovereignty. Painting from the collection of the Tropenmuseum in The Netherlands_Una representación de la victoria etíope contra los italianos en la Batalla de Adwa (1896).

El imperio de Etiopía quedó independiente durante la era de dominio européo en África; este hecho histórico fue de suma importancia al nacimiento de un movimiento afro-caribeño cuasi-bíblico: el Rastafarianismo. Robert Nesta Marley permanece el “Rasta” más famoso mundial.

Tontos tercos

.

Tontos tercos, piensan que son ‘cool’

para negarme la simplicidad.

Sí, tu te has ido por largo tiempo

Con tu amor por vanidad ahora.

Sí, tu tienes mala interpretación

Mezclada con vana imaginación.

.

Así que toma el Sol de Jah, la Luna de Jah y la Lluvia de Jah, las Estrellas de Jah,

Y para siempre, sí, borra tu fantasía, yeah-yeah.

.

Los labios del justo enseñan a muchos,

Pero los necios mueren por falta de entendimiento.

La riqueza del hombre rico está en su ciudad;

La riqueza de los justos está en su santo lugar.

.

Así que toma el Sol de Jah, la Luna de Jah y la Lluvia de Jah, las Estrellas de Jah,

Y para siempre, sí, borra tu fantasía, yeah-yeah.

La destrucción de los pobres esta en su pobreza;

¡La destrucción del alma es la vanidad, sí!

.

Entonces, tontos tercos, piensan que son ‘cool’

Para negarme la simplicidad, yeah-yeah.

Sí, tu te has ido por largo tiempo

Con tu amor por vanidad ahora.

¡Pero yo no quiero ya las reglas!

¡No quiero ser tonto ya!

Yo no quiero ya la escuela:

Cosas tuyas..¡puede ser que nunca sepamos de ellas!

.

Sí, tienen mala interpretación

Mezclada con vana imaginación…

Tontos tercos, ¡piensan que son ‘cool’

Para negar a mí, ooh-ooh, la simplicidad!

. . .

Marley utiliza unas frases biblicas en sus letras aqui: por ejemplo, Proverbios 10, versos 15 y 21.

. . .

Bob Marley & The Wailers: “Stiff-necked Fools” / “Tontos tercos” fue grabado en 1980 y lanzado póstumamente, en 1983. Puede oír el sonido frágil de la voz de Marley, porque sufría del cáncer que pronto le mataría…

http://youtu.be/0sBrvhMeGlw

.