Andre Bagoo: “I am the Archipelago”: Eric Roach and Black Identity

Posted: February 28, 2015 Filed under: 7 GUEST EDITORS, Andre Bagoo, English, Eric Merton Roach | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Andre Bagoo: “I am the Archipelago”: Eric Roach and Black Identity“I am the Archipelago”: Eric Roach and Black Identity

By Andre Bagoo

.

THOSE who know Eric Roach, know how the story ends. This year marks the centenary of the Trinidadian poet who was born in 1915 at Mount Pleasant, Tobago. He worked as a schoolteacher, civil servant and journalist, among other things. Along the way, he published in periodicals regularly. But in 1974, he wrote the poem ‘Finis’, drank insecticide, then swam out to sea at Quinam Bay. The first-ever collected edition of his poetry only appeared two decades after his death. In it, Ian McDonald describes Roach as, “one of the major West Indian poets”. He places Roach alongside Claude McKay, Derek Walcott, Louise Bennett, Martin Carter and Edward Kamau Brathwaite.

.

Too often is the discourse on Roach coloured by his story’s ending. We cannot ignore the facts of what occurred at Quinam Bay, yes, but sometimes they distract from the poet’s genuine achievements. Notwithstanding the emerging consensus on his stature, he is still best known for his ill-fated death. Yet the journey is sometimes more important than the destination.

.

In an introduction to the same collected edition of Roach’s poems published by Peepal Tree Press in 1992, critic Kenneth Ramchand states: “in the English-speaking Caribbean, is there anyone who had written as passionately about slavery and its devastations before ‘I am the Archipelago’ (1957) hit our colonised eardrums?” Ramchand notes that Roach was, “committed, as selflessly and as passionately as one can be, to the idea of a unique Caribbean civilisation taking shape out of the implosion of cultures and peoples in the region.” For Ramchand, “the ultimate justification of [Roach’s] art would be that it contributed to the making and understanding of this new, cross-cultural civilisation.” That cross-cultural civilisation is the one Walcott speaks of when he remarks:

.

Break a vase, and the love which reassembles the fragments is stronger than the love which took its symmetry for granted when it was whole….This gathering of broken pieces is the care and pain of the Antilles….Antillean art is this restoration of our shattered histories, our shards of vocabulary, our archipelago becoming a synonym for pieces broken off from the original continent.

.

This is really a call for the new breed of Caribbean poets, the breed that reverses colonialisation’s history of plunder. Just as our colonial overlords of the past have done, poets, now, are free to pillage from whichever continent they choose. This is not a process of retribution, but rather the restoration of the resilience of the human spirit itself amid the sea of history. It also asserts the reality of the fact that we are as much a part of world culture as anyone else and cannot be marginalised from it.

.

Roach – sometimes called the “Black Yeats”– was one in a long line of poets for whom imitation and allusion are, in fact, blatant acts of rebellion. He also saw himself as key to the process of forming a West Indian Federation, a political union which he felt required a new poetry. Though that union never came to pass, Roach’s work still serves to engage key aspects of Caribbean identity.

The narrative of Black identity, whatever that may be, has to some extent played on the idea of separate black and white races. It has also called for a rejection of “white” ideas and a return to African ideas. But these are uneasy dichotomies which paper over the realities of history over time, the mixing of races and the idea that race itself is an invention. At the same time, these categories ignore the complexity of colonisation. That process of colonisation saw states and peoples being exploited for economic resources and then, in the mid-20th century, abandoned by colonial motherlands under the pretence of liberation – even as strong economic subservience remains in place to this very day.

.

And this is why Roach remains relevant: he not only asserts that the English language is as much ours as theirs, but also sings of the true implications of history, a history sometimes obscured by neat narratives of “independence” and “emancipation”. This is why Roach is still alive.

. . .

I AM THE ARCHIPELAGO

.

I am the archipelago hope

Would mould into dominion; each hot green island

Buffeted, broken by the press of tides

And all the tales come mocking me

Out of the slave plantations where I grubbed

Yam and cane; where heat and hate sprawled down

Among the cane – my sister sired without

Love or law. In that gross bed was bred

The third estate of colour. And now

My language, history and my names are dead

And buried with my tribal soul. And now

I drown in the groundswell of poverty

No love will quell. I am the shanty town,

Banana, sugarcane and cotton man;

Economies are soldered with my sweat

Here, everywhere; in hate’s dominion;

In Congo, Kenya, in free, unfree America.

.

I herd in my divided skin

Under a monomaniac sullen sun

Disnomia deep in artery and marrow.

I burn the tropic texture from my hair;

Marry the mongrel woman or the white;

Let my black spinster sisters tend the church,

Earn meagre wages, mate illegally,

Breed secret bastards, murder them in womb;

Their fate is written in unwritten law,

The vogue of colour hardened into custom

In the tradition of the slave plantation.

The cock, the totem of his craft, his luck,

The obeahman infects me to my heart

Although I wear my Jesus on my breast

And burn a holy candle for my saint.

I am a shaker and a shouter and a myal man;

My voodoo passion swings sweet chariots low.

.

My manhood died on the imperial wheels

That bound and ground too many generations;

From pain and terror and ignominy

I cower in the island of my skin,

The hot unhappy jungle of my spirit

Broken by my haunting foe my fear,

The jackal after centuries of subjection.

But now the intellect must outrun time

Out of my lost, through all man’s future years,

Challenging Atalanta for my life,

To die or live a man in history,

My totem also on the human earth.

O drummers, fall to silence in my blood

You thrum against the moon; break up the rhetoric

Of these poems I must speak. O seas,

O Trades, drive wrath from destinations.

.

(1957)

. . .

Andre Bagoo is a Trinidadian poet and journalist, born in 1983. His second book of poems, BURN, is published by Shearsman Books. To read more ZP features by Andre Bagoo, click on his name under “Guest Editors” in the right-hand column.

. . . . .

The Rwanda Genocide, twenty years later: 100 Days of photographs + poems by Wangechi Mutu and Juliane Okot Bitek: Days 43 to 1

Posted: July 18, 2014 Filed under: 7 GUEST EDITORS, English, Juliane Okot Bitek | Tags: Wangechi Mutu: 100 days of photographs for The Rwanda Genocide Comments Off on The Rwanda Genocide, twenty years later: 100 Days of photographs + poems by Wangechi Mutu and Juliane Okot Bitek: Days 43 to 1

. . .

Juliane Okot Bitek

100 Days: a poetic response to Wangechi Mutu’s #Kwibuka20#100 Days

.

Day 1

I have nothing

I stand before you with nothing

I am nothing

You stand before me with nothing

I don’t know what I know

but I know that you know nothing

Having come from nothing

To nothing & from nothing

Let my nothing meet your nothing

We may find something there.

.

Day 2

This will not be a litany of remembrances:

We know who the guilty are

The guilty know themselves

This is a charge against the witnesses

& those who cannot speak

This is a charge against those who speak incompletely

& incoherently

Against nature who saw everything & did nothing

against the bodies that dissolved

& the ones that refused to dissolve

those that insisted on writing the landscape with bones

This is a charge against pain

against heartbreak

against laughter

against the dead.

.

Day 3

We were pock-marked by these things:

a torrent of accusations

bayonet sticks

lies

We were mocked

by faith in tiny shards

by the cross, with its pliant figure

representing grace

or representing the presence of God

What God in such a time?

What God afterwards?

What God ever?

Day 4

Acel ariyo adek angwen

Acel ariyo adek angwen

Acel ariyo adek angwen

Acel ariyo adek angwen

Acel ariyo adek angwen

Acel ariyo adek angwen

We have run out of days

.

Day 5

What do I remember?

Nothing but the contagion of stories

What do I want to say?

What do I want to say?

.

Day 6

Images from those days return like silent movies

The available light of the rest of this life and I

can’t hear anything

Just the silent movies

.

Day 7

Then we stumbled into the place where words go to die

& where words come from

First we bathed in it like sunbathers

then we washed ourselves in it

we rinsed our mouths out

shampooed our hair

swam in the words

& at night

we covered ourselves in words

& went to sleep

at night

the nightmares returned

but the dreams also came

.

Day 8

Justice woke up and went to work

but no one showed up

Justine, not justice, went to work

but no one showed up

Justice and not Justine

woke up and went to work

but no one showed up

women woke up and went to work

no one knows what Justine and/or

Justice are doing these days

.

Day 9

These days

circle and circle

some days soar from above like kites

others circle around and around

like hyenas waiting for the story to die

some sit

some stand on long legs

vultures wait

some stay some change seats

others come and go

some dive in

some walk, crawl, cycle

dial on the radio to listen

to stories in embers

stories aflame

stories in stories

stories stoking stories

stories stalking stories

stories in circles & circles

those stories haven’t yet killed me

.

Day 10

What indeed

constitutes

the criminalizing function

of language in media?

Stuffed

Hacked

Punched

Pumped full of bullets

Slaughtered

& left to rot on the street

Pigs

Dogs

Cockroaches

People murdered

Calculated and rated on a per hour basis

& sometimes exacted to ethnic & tribal

differences

struggles

divisions

clashes

Never people you know,

Until they are.

.

Day 11

Savage savage savage

savagesavagesavage

sa vedge sa vedge

sav edge sav edge

save edge save edge

saved saved

saved

.

Day 12

What now?

That we must create our own world

That we use the right words for the world we want to live in

Like God: Let there be light

And there was light

Let us forgive our enemies

Let us be good examples for the next generation

Let us belong to one another

Let us be friends

.

Day 13

There was a rainbow in that sky,

the day a chain-linked fence separated us.

You probably saw the rainbow in the sky;

The chain-linked fence, you probably saw it as well.

.

Day 14

Now their eyes flit flit flit,

dragonflies in the afternoon,

their hands are calm as they write

but clammy in the handshake

– what can we do for you?

– what can we do for you?

Their eyes like dragonflies,

what can they do for me?

.

Day 15

And so I am now a slow burning woman

Creeping through time like a gecko through a tree

I’m shedding skin then eating it up

Shedding skin then eating it as I crawl along

Height like time has a hazing effect

but wonder remains

exclusive to the uninitiated

.

Day 16

We were the carriers of the events

Days and nights worked in tandem

to make us forget

We carried proof of place & proof of time

We recited these details over & over

We marked our steps

We marked the cadences into a rhythm & held them close to heart.

.

Day 17

This is the horror that did not turn you into stone.

This the poem, the mirror with which you can behold

that you did not turn into stone.

This is true: you’re still not stone.

Day 18

Yesterday tripped and fell into evening

As it plunged deep into the night, voices rose up

from the abyss:

Come! Come!

They called

Come!

We never slept, trying to makes sense

whose voice was whose

Yesterday tripped and fell into a long night

of calling, of voices beckoning, recalling

things done, things undone by time

Today, I’m trying to sort out the differences

whose voice was whose

which place, what time

They all sound the same now

— the dead and the unborn;

they all sound the same.

.

Day 19

So this is what the Greek storyteller foretold:

First, the pity-inducing event,

Those poor, poor people,

Pity in the numbers, pity in the grotesque photos that followed,

the writing and the reading that followed.

There was nothing, nothing we could have done different;

Everything was beyond us.

Then came the fear it would spread like contagion,

Uncontrolled like a forest fire.

Now it is time for catharsis.

.

Day 20

It has been called a harvest of death.

It was more like a net that was cast,

A fisher net

A fisher net cast by a man

A fisher of men

– Christ, was that you?

.

Day 21

A ring around a rosie

A ring around a posy

A ring around a peony

A ring around a buttercup

A ring around a baby’s breath

A ring around a bouquet

A pocket full of posers

A pocket full of diamonds

A pocket full of memory

A pocket full of justice

A pocket full of ideas

A pocket full of shit

Ring around a rosy

A pocket full of posies

Achoo! Achoo!

We all fall down!

.

Day 22

Twenty years later we’re young again

as we should be

Welcome to this country

Welcome

Come and see how we live

Come and see how we get over everything

Come and see how we exhibit skulls

Come and see how we caress skeletons and tell stories about who these bones were

Come and see how easy we are with things;

Come and visit.

Our country is now open for tourism.

.

Day 23

Some of us fell between words

& some of us onto the sharp edges

at the end of sentences

And if we’re not impaled

we’re still falling through stories that don’t make sense

Day 24

& then there was just the two of us

everything in flames

There was the two of us

your arm around my shoulder

mine around your waist

we hobbled on

just the two of us

we hobbled on

just the two of us for a while

& then there was just me

.

Day 25

Bones lie

Bones lie

Bones lie

About their numbers and bits and parts

Bones lie in open air, in fields, under brushes, along with with others in state vaults,

in museums as if they belong there

in piles, as if they would ever do that in life.

Bones lie about being dead

bleached

broken

pulverized, as if we who are not all bone

don’t live with nightmares

Bone have nothing to say

Nothing about who it was that loved them the most

.

Day 26

That day dared to set

As did the one after it and the one after that

Days became long nights

That became mornings which appeared innocent

of the activities of the day before

That day shouldn’t have set

The next day

if that other day had collapsed from exhaustion, should have held the night sky at bay

That day should have remained fixed in perpetuity

so that we would always know it to be true

.

Day 27

Glory be to the Father to whom all this is His will

Glory be to the Son who claims to have died for the sins of all men

Glory be to the Holy Spirit that guides the tongues of flames of the believers

As it was in the beginning

As it was in the beginning

As it has always been

As long as we need to hark back to a beginning

that only exists in the memory of the elusive Trinity who can only be accessed through Faith

Nothing will ever change

Nothing will ever change except by Faith

So nothing will change

.

Day 28

When I (survey) look out at the world around me

(The wondrous cross)

On which (the Prince of Glory) every one that I loved died,

(My richest gain) My richest gain? My richest gain?

I count (but) as loss

It was all loss – all of it

And so I pour contempt on all (my) the pride

That seems to think that there is anything to celebrate.

Don’t ever forbid it, Lord,

That I should (boast) dare to speak out

(Save in) on the deaths

(of) Christ, my God, everything, everything that mattered,

All the vain things that charm (me) You most – the sky scrapers, the clean streets

& the moneyed vendors

(I) You sacrifice (them) Your own morality (to His blood)

There is nothing to party about, nothing.

See from (His head, His hands, His feet) this vantage point

Just how much sorrow and love and bone and blood flow mingling down

Did e’er such love and sorrow meet? Did ever?

Where did ever such a twisted sense of wreath-making come from?

Or why would thorns compose so rich a crown?

Can you not read the land?

Were the whole realm of nature mine

That were a present far too small

Love so amazing so divine

Demands my soul, my life, my all

So it took my soul, my life, my all.

.

Day 29

Time is a curve

so long that it seems to be a straight line

I can see myself walk away

I see

& then remember my heel striking the ground first

the weight of my shoulders

the back of my head & the low hang of my neck

Circle forward

What does my face matter if my heel is still cracked?

Day 30

A grid

a fence

a field

some grass

some stumbling

a ditch

mud

a broken slipper

a tear

a sheet

some fumbling

a groan

a metal plate with a faded rose in it

a rusty kettle that will never boil.

.

Day 31

Here: it is daytime now

We’re here

It is now twenty years after a hundred days that we did not plan on living through

We wanted to, prayed, yearned to make it

Not that those who didn’t didn’t

.

Day 32

In Eden

We heard birdsong and didn’t hear it

We saw the soft flutter & sail of a falling leaf, but we didn’t know how to read it

We worked the earth, lived off it, trampled it back and forth, back and forth

In Eden

We never thought about the difference between house and home

we never even thought to call it; we were it, it was us and ours

gang wa

Now as we fall unendingly

we know different

we understand belonging as transitory at best

& as elusive as the future we once imagined.

.

Day 33

So we mothed along towards the fire

With the full knowledge that there couldn’t be anything else beyond this

We mothed along

with bare arms, wingless

a light step here

a light step there

sometimes no step at all

& other times dreamless stops

We mothed along knowing that it was possibly death

& not fire that beckoned

.

Day 34

So we saw, tasted, smelled, touched, felt and heard what we knew to be true

We had to see, taste, smell, touch, feel and hear in order to know this word

–genocide?

How much made it valid?

Would one less death have disqualified those hundred days from being called a genocide?

And more?

.

Day 35

There’s no denying the flap of an angel’s wings

for someone who felt it fan her face in those days

The salve of a gentle touch

The stretch of an arm to catch you as you reached for the top of the wall

the strength of a wail

the depth of a moan

the light of unending days

the consistency of seasons

as real as angel wings

There is, however, a slope that leads

from these days of fiction

into nightmares that are real.

.

Day 36

Oh, I curse you.

I curse you long and hard and deep and wide

I curse you with fire from my mouth

I join everyone with fire in the mouth

Wherever we live & wherever we lay

We curse you, we curse you, we curse you.

.

Day 37

When Christ lost a beloved friend, he cried out:

Lazarus!

Lazarus, come out of the tomb

Lazarus, come out of the tomb

Imagine Christ crying for the beloved on this land:

Lazarus! Lazarus! Lazarus! Lazarus!

Lazarus, come out of the tomb!

Imagine Christ with a croaking voice:

Lazarus, Lazarus, Lazarus

Christ in a whisper

Christ mumbling:

Lazarus, Lazarus

Christ spent

Christ crumbled

Oh, Lazarus

Christ either had no idea of these one hundred days

Or he must have lost his voice in the first few moments

Christ may just have not been capable

He might have noted the endless and boundless losses of the beloved on this land

He might have hung his head down, powerless in the face of this might

Christ, look to your mother

ask her to pray for your intercession.

.

Day 38

If there’s a breeze tonight

We might think for a moment that it is sweet

There is a breeze tonight

& it is sweet

I can’t remember if the breeze was sweet in those days

There was a breeze

There might have been

Why not?

It might have been the same sweet breeze that kept us from burning

.

Day 39

If we were to go back to the time before these hundred days

We couldn’t return without knowing what was to come

How could we?

If we were to swear off, that we couldn’t return to these days

I don’t know that we could; we know

We’re marked by this knowing

We know that we’re marked

& this knowledge taints us

& so we can never absorb your innocence

But

Your innocence will not shield you from these days

Because your innocence does not cleanse

& so your innocence cannot save you from what you must know.

.

Day 40

She is my country

Every time she goes

I am a leaf in the wind

Every time she goes

She takes with her

All the home that I can ever claim

What use do I have for the carrier of bones?

What anthem can I sing for the graves of children?

She holds my home in the country that she is

& every time she returns, she is my flag

& I am home again.

.

Day 41

If justice was in a race with time

Peace would have no medal to offer

If peace sat at the table with justice

Time wouldn’t be served

If time wanted justice, so bad, so bad,

There would be nothing that peace could offer

Either by seduction or reason

.

Day 42

I kneel before you

I kneel before you but this is not an act of supplication

I kneel before you because I cannot stand

I kneel before you because I cannot speak right now

My gestures are wordless articulations

& the dark in my eyes is not an indication of anything you could imagine

& there is nothing, nothing that you could ever give me

Day 43

After all the madness,

& it had to have been a madness,

You hear the arguments and explanations

That it was inevitable

That it was coming

That it had to happen after all those years

Knowing what we know now

What else should we have expected?

I hear that my loss was inevitable

I hear that my loss was coming

I hear that my heartbreak was written in the stars

& in historical documents & even in the oral stories

We had to have been blind & deaf & dumb to not have known

We had to have been oblivious, thinking that we could live

to a full life of family and community like others

After all, who misses the inevitability of a mass event like a genocide?

. . .

To see / read Days 100 to 44, click on the ZP link below:

https://zocalopoets.com/2014/05/31/the-rwanda-genocide-twenty-years-later-100-days-of-photographs-poems-by-wangechi-mutu-and-juliane-okot-bitek-4/

. . . . .

In Search of Dylan Thomas: Andre Bagoo in Wales

Posted: July 12, 2014 Filed under: 7 GUEST EDITORS, Andre Bagoo, English Comments Off on In Search of Dylan Thomas: Andre Bagoo in WalesAnd all your deeds and words,

Each truth, each lie,

Die in unjudging love.

Dylan Thomas, ‘This Side of the Truth’

SUNDAY

WE ARE in the strangest town in Wales.

It is a Sunday afternoon and we walk through the lych-gate and up the long asphalt path leading to the church. Where is his grave?

The path forks. To the left, a graveyard and St Martin’s. To the right, another graveyard, added more recently. The sun is setting.

St Martin’s Church has a service every Sunday at 6 pm. We hesitate at the entrance. Is a service going on? Will we interrupt the worshippers inside? From behind the thick 13th century walls, we can hear the faint sound of an organ. Are those voices? The wind.

We walk in. A small group of old ladies—and one or two men—are huddled together in the sacristy at the far end. There are shields and flags and statues. The stained glass makes everything a kaleidoscope. On one wall near the back (where we stay, looking on respectfully) is a plaque in honour of him, bearing two of his verses: “Time held me green and dying / Though I sang in my chains like the sea”. The light seems dazzled by these words, throwing long shadows on the rough stone walls.

Everyone in the church is kind, weirdly so.

“What took you so long? You should have come inside sooner,” one lady says.

“Here for Dylan Thomas, are you?” the rector adds, greeting us after the service and shaking our hands warmly.

Outside, we search among the graves and give up trying. It is quiet, the light is dying. We are tired after travelling for half a day. We will come again, we say, later in the week.

. . .

In the bar of Brown’s—the guesthouse/pub where Dylan Thomas spent most of his time drinking—the young bartender struggles to explain it. A sign on the wall advertises Laugharne as “the strangest town in Wales”.

“You’ll understand after a while,” he says, pouring a pint. “People here are really, really nice.” He says we are lucky the town is dead, because hundreds – if not thousands – of tourists will come for the Dylan Thomas centenary later this year. Our bartender is the youngest man we see all week.

A couple from a rival guesthouse a few blocks down on King Street stop in for drinks. They stare at us.

“You’re both so beautiful,” Janet says, eyeing my hamburger. Her husband, Peter, whispers into my ears that he has a hearing problem. She tells us a story about how she met Peter, who is her second husband. After her first marriage she was single for 17 years, she says, proudly. Then, she met Peter through an advertisement in the newspapers. She gives us a card for their inn, and says they have better rates. She never mentions her first husband’s name.

“She could get away with murder,” Peter jokes before they leave. I take a picture of them – just in case. That night in bed, I think of the town’s famous clock tower, standing black and white against the sky, just two blocks away.

MONDAY

Dylan Thomas was born in Swansea one hundred years ago, in 1914. He worked briefly as a reporter before his first published poem (‘And Death Shall Have No Dominion’) appeared in 1933. He skyrocketed. His stentorian voice and beautiful language made him particularly popular over the wireless; his most famous work – Under Milk Wood – was, in fact, written for radio.

Thomas spent two major periods of his relatively brief life at Laugharne. He lived there when he first married. Then, after living in several different places (London, Oxfordshire, Iran) he returned, settling with his family in a boathouse overlooking the estuary at the mouth of the River Tâf. Near the end of his life, he developed a routine at Laugharne, right up until his trip to New York in October 1953. (It was there, after a night of heavy drinking, that he died at St Vincent’s Hospital.) He made his third, and final, voyage to Laugharne, where he was buried at St Martin’s graveyard. Thomas was 39.

Today, the grave looks fresh, covered with yellow, red and purple flowers. A simple white cross marks the spot where the poet who was once Wales’ most famous son is buried. “In Memory of Dylan Thomas,” it says. His wife Caitlin, who had a tempestuous relationship with him and who had not been with him in New York, would, years later, have the last word. She was buried in the same plot, and the other side of the slender white cross carries her name. There is no poetry at the grave.

TUESDAY

When you travel, nothing is as it seems. Everything has something of the air of the unreal. Each city, town, inhabitant, each landscape – becomes a mirage. But to the persons who live there, you are the one who is out of place. You are the apparition.

THURSDAY

It seems every single thing in Laugharne is connected to Dylan Thomas. Or if it is not, it fast becomes so. The entire town is a memorial to him; a living and breathing tomb. It is a monument comprising: pubs, book-shops, a clock-tower, ruins of a gothic castle, and St John’s Hill.

And all of this can be found in Thomas’ poetry.

But how much of a poet’s life and circumstance do we need to know? Do we need the back-story in order to enjoy each poem? Is it not better the less we know? Must we see the writing-shed, learn of the love affairs in New York, visit the favourite drinking haunts, the neighbours, the aunties? Of poetry Thomas once said:

All that matters about poetry is the enjoyment of it, however tragic it may be. All that matters is the eternal movement behind it, the vast undercurrent of human grief, folly, pretension, exaltation or ignorance, however unlofty the intention of the poem.

You can tear a poem apart to see what makes it technically tick, and say to yourself, when the works are laid out before you, the vowels, the consonants, the rhymes or rhythms, ‘Yes, this is it. This is why the poem moves me so. It is because of the craftsmanship.’ But you’re back again where you began. You’re back with the mystery of having been moved by words. The best craftsmanship always leaves holes and gaps in the works of the poem so that something that is not in the poem can creep, crawl, flash or thunder in.

I use everything and anything to make my poems work and move in the directions I want them to: old tricks, new tricks, puns, portmanteau-words, paradox, allusion, paranomasia, paragram, catachresis, slang, assonantal rhymes, vowel rhymes, sprung rhythm. Every device there is in language is there to be used if you will. Poets have got to enjoy themselves sometimes, and in the twistings and convolutions of words, the inventions and contrivances, are all part of the joy that is part of the painful, voluntary work.

With Thomas, there is a focus on what is not in focus: on crafting effects and experiences within the poem which hint at deeper ebbs. In addition to the devices he lists, there is also careful attention to form and an overriding sense of rhythm which propels the poetry, giving it a zealous, almost evangelical energy.

Many of his poems reflect these qualities, including some of his best-known, such as: ‘And Death Shall Have No Dominion’, ‘Poem in October’, ‘Fern Hill’, and ‘Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night’. A good example is also his poem ‘Twenty-four years’:

Twenty-four years remind the tears of my eyes.

(Bury the dead for fear that they walk to the grave in labour.)

In the groin of the natural doorway I crouched like a tailor

Sewing a shroud for a journey

By the light of the meat-eating sun.

Dressed to die, the sensual strut begun,

With my red veins full of money,

In the final direction of the elementary town

I advance for as long as forever is.

Thomas deploys rhyme, alliteration, paragram, memorable and unexpected imagery (“meat-eating sun”; “red veins full of money”) all to commemorate a moment; a feeling. The opening line startles, inverting the normal cause and effect relationship we associate with the provocation of tears – it bathes the poem in ambiguity. The poem is, for me, an act of grief, and seeks to point to a life force able to overcome it (“bury the dead for fear that they walk”). Ultimately, this is a snapshot as meaningful or as meaningless as life itself, grieved for or celebrated.

But if for Thomas poetry’s enjoyment is conditional upon a kind of cultivated mystery to the text, how useful is it to scour over the biographical details of Thomas’ undoubtedly tumultuous life? While Laugharne was central to his persona, is Laugharne central to the poetry? The whole point of poetry, according to Thomas, was its experience. Would he advocate that school of thought which states the reader need not get distracted or bogged down by the details of the poet’s personal life?

FRIDAY

The Dylan Thomas Walk is approximately two miles in length and takes you uphill around the shoulder of St John’s Hill, which overlooks Laugharne. Along the walk, we see views of the marshy Tâf estuary, which fans open like a sponge at low-tide; of Thomas’ boathouse; the Gower; north Devon; Caldey Island and Tenby. If you’re keen you can download an app specially made for the walk (https://itunes.apple.com/gb/app/dylan-thomas-100-birthday/id571021072?mt=8&ign-mpt=uo%3D4).

This “walk” was opened in 1856 by the Laugharne Corporation to enable cocklers to access by foot the valuable cockle beds on the upper and lower estuary marshes, when the dangerous high tides below would prevent access along the old cart road. Today, the path has been turned into a walk commemorating Thomas’s poem, ‘Poem in October’, which is ostensibly an occasional poem written by Thomas to mark what was his 30th birthday on October 24, 1944.

Reading ‘Poem in October’ today it remains as vital and alive as it must have been in 1944. Thomas was writing during World War II and perhaps this context alone gives the poem a certain charge. His retreat to the Laugharne landscape allows a perspective and distance. The marsh environment comes to mirror the processes not only of war, but of economy and society generally. But reading the poem on the page is nothing like reading the poem along the specially-designed walk which now exists. At several spots, stations have been made bearing sections of the poem relating to the landscape, as well as old, faded maps and drawings of the view. Only by taking the Dylan Thomas Walk can you fully appreciate what he meant when he wrote:

My birthday began with the water-

Birds and the birds of the winged trees flying my name

Above the farms and the white horses

And I rose

In rainy autumn

And walked abroad in a shower of all my days.

High tide and the heron dived when I took the road

Over the border

And the gates

Of the town closed as the town awoke….

Pale rain over the dwindling harbour

And over the sea wet church the size of a snail

With its horns through mist and the castle

Brown as owls

But all the gardens

Of spring and summer were blooming in the tall tales

Beyond the border and under the lark full cloud.

There could I marvel

My birthday

Away but the weather turned around.

If we admit the landscape is in the poem, is the life not there too? Is the poem – even when stony, mysterious, obscure – not an artifact of a life, however shrouded in mystery? And if the life is there, can learning about the poet enrich our appreciation of what he sets out? For me, ‘Poem in October’ is a richer experience having been to Laugharne. Reading a poem is like reading a poet and, in turn, everything that has touched him. In this way, the reader and poet converge and something universal sparks between them. This is not to say this is compulsory to the enjoyment of a poem, or to advocate the limited readings so often lazily slapped onto poems when people find out about the lives of the poet, but rather to acknowledge that sometimes more information can reveal and deepen mystery simultaneously. Sometimes, the more you know, the less you know. And the more we know of a poet, the more possibilities are inherent in the text the poet leaves behind, even if the poem, like the poet, remains unknowable.

. . . . .

Juliane Okot Bitek: 100 Days: a poetic response to Wangechi Mutu’s #Kwibuka20#100 Days

Posted: May 31, 2014 Filed under: 7 GUEST EDITORS, Juliane Okot Bitek | Tags: May 2014 Zócalo Poets Guest Editor Juliane Okot Bitek Comments Off on Juliane Okot Bitek: 100 Days: a poetic response to Wangechi Mutu’s #Kwibuka20#100 DaysThe Rwanda Genocide, twenty years later: 100 Days of photographs + poems by Wangechi Mutu and Juliane Okot Bitek

Posted: May 31, 2014 Filed under: 7 GUEST EDITORS, English, Juliane Okot Bitek | Tags: Wangechi Mutu: 100 days of photographs for The Rwanda Genocide Comments Off on The Rwanda Genocide, twenty years later: 100 Days of photographs + poems by Wangechi Mutu and Juliane Okot BitekThe Rwanda Genocide (April to July, 1994) was one of the 20th century’s many horrific episodes in what has come to be known by the clinical phrase of “ethnic cleansing”. The Genocide was the culminating event in a civil war involving the Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa peoples, and 800,000 people were killed in a mere three months. Both perpetrators and victims have had to re-build their traumatized nation, coming face to face with each other’s capability for depravity and also with that miraculous human need to acknowledge what happened – and to forgive.

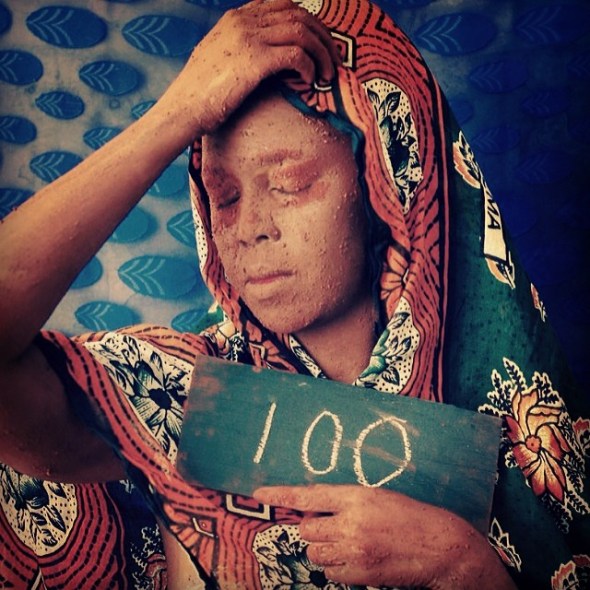

When I tell you that the photographs of Wangechi Mutu are poems I honour her visual artistry in the highest way I know how: to give it the name of that uniquely human skill – poem-making – that I value above all else. At Day 100 she commenced with a moving image of a clay-caked woman whose eyes were – mercifully – closed. Other human figures followed. Why were they all women? Was it because it is mainly men who do these mass-killings worldwide? Then came photographs of limbs – hands, feet, bodies bagged – and these are piercingly close to “documentary” photography.

But she goes further still with images completely devoid of people or their “parts”. These may be the most powerful of all. Because of the hand-drawn number cards placed somewhere within each photograph, these person-empty pictures seem to indicate that something we cannot look upon has been left out. My mind wanders toward a hacked-up body dumped at a building site or an abandoned lot; by a rusty gate or in the loneliest corner of a concrete yard.

.

Juliane Okot Bitek happened to see Wangechi’s first Instagram picture, Day 100, from April 6th, 2014 – that being the 20th anniversary of the beginning of those awful events of The Genocide. And she responded as only a poet might do: to commit to an epic poem-making journey for 100 numbered poems. If Wangechi’s pictures are raw or allusive, Juliane’s poems are everything that words are most suited for: questioning/wondering aloud; feeling all feelings, wherever they go / thinking all thoughts, though they be inconclusive. This is the very core of poetry, and there is no other kind of language that can handle such horror and humanly touch all the marks: to speak of the un-speakable. It is Poetry alone that best honours suffering, loss, shame, responsibility.

Wangechi Mutu and Juliane Okot Bitek are both African-born. Each has lived far away from the land of her birth for a long time now – Wangechi in Brooklyn, New York, and Juliane in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Is it possible that the geographical distance each has achieved – from Kenya and Uganda respectively – both countries having felt seismic social effects from the terror of Rwanda’s Civil War – has helped them to turn Pain into Art? For this is, surely, one of the greatest goods of artistic achievement: to do something beautiful with our pain. These two artists – one a collagist and sculptor who is experimenting with photography for the first time, the other a poet who is creating epic poetry in real time – merge empathy, an imaginative rendering of the facts, and the search for meaning to create unique works-in-progress: call them 100 Days.

.

We invite our readers to scroll down through ZP May 2014 to read and reflect upon Juliane’s poems and to behold Wangechi’s photographs thus far. And to click on the links below and follow their journey through June and into July – until they have reached Day 1.

Alexander Best

Editor, Zócalo Poets

May 31st, 2014

. . .

https://www.facebook.com/hashtag/kwibuka20?source=feed_text&story_id=624576410970511

http://www.julianeokotbitek.com

. . .

Juliane Okot Bitek

100 Days: a poetic response to Wangechi Mutu’s #Kwibuka20#100 Days

.

Day 44

A hundred days of shallow breathing interspersed with deep sighs

A hundred days zooming into nothing

A hundred days of years and years that morphed into decades

of life as a gift, of life as worth living

A hundred days on a hundred days-ing, we weren’t counting

It wasn’t as if after all those days

a veil would lift and it would have taken just those days, nothing more

It wasn’t as if after all those days

there was a chance that normal would morph back

as if all the seeds that had sprouted in those one hundred days

would un-sprout themselves into nothingness

.

Day 45

We watched as faith crumbled off the walls in dull clumps

We watched as prayers dissipated into clouds which then returned as drizzle to mock us

Although sometimes it rained

& sometimes it rained hard, as if the earth was sobbing

but it was never so – the earth remained dispassionate to our circumstances

Eventually our superstitions burst like bubbles

or floated away like motes in the light

There was nothing left to hold on to, not even time which stretched and then crunched itself wilfully

Cats and dogs roamed about, feral and hungry,

People crouched in the shadows, not all feral and all the time hungry.

At a half past all time, even decay stopped for a moment

Ours remains Eden, not even a spate of killing can change that.

.

Day 46

If truth is to be known in order to be acknowledged, then this is the truth that we know:

we know the numbers

we know the number of days

we know the circumstances

where the machetes came from and who wielded them

where the dotted line was signed

we know who fled

who advanced while chanting our names out loud

the names they called us

and the papers and airwaves on which these names can still be found

we know who claim to be the winners & the victims

we know where the markers are for where we buried the children

we know the cyclical nature of these things

the impossibility of knowing everything that happened

we know that the true witnesses cannot speak

and that those who have words cannot articulate the inarticulable

we know that there are those who died without telling what they knew

we know that there are those who live without telling what they know

we know that some people choose to tell and some stories choose to remain untold

.

Day 47

I remember how my sister used to look up when she remembered

Sometimes she would have a small laugh before she started to recall a story

Often she’d be laughing so hard at the reveries that we all started to laugh

Soon enough we were all laughing so hard because she was laughing

And then she laughed because we laughed

And the memory of that story dissolved into the laughter and became infused with it

My sister is not here anymore

I wonder if she remembers laughing

I wonder if she remembers anything

Day 48

So what is it to be alive today?

I no longer think about the hard beneath my feet

or the give of my body into sleep

or the way my skin used to dissolve so deliciously from touch

Is this what it is to become a haunt?

.

Day 49

There we were, lining up like frauds

There we were, receiving medals and commendations

like frauds

There we were, listening to speeches and reading the adorations

about us as heroes – like frauds

There we were

holding in ourselves, like frauds

All we did was stay alive

While many, many others died.

.

Day 50

This is the nature of our haunting:

silent witnesses & silence itself

neither revealing nor capable

of explication

of what any of that meant

What do we need nature for?

All it does is replicate its own beauty.

. . .

The Rwanda Genocide, twenty years later: 100 Days of photographs + poems by Wangechi Mutu and Juliane Okot Bitek

Posted: May 24, 2014 Filed under: 7 GUEST EDITORS, English, Juliane Okot Bitek | Tags: Wangechi Mutu: 100 days of photographs for The Rwanda Genocide Comments Off on The Rwanda Genocide, twenty years later: 100 Days of photographs + poems by Wangechi Mutu and Juliane Okot BitekJuliane Okot Bitek

100 Days: a poetic response to Wangechi Mutu’s #Kwibuka20#100 Days

. . .

Day 51

I waited for my heart to harden after the kids were gone

I waited for the years of love to dissolve as if they never happened

I waited for the day when the remembrances of silly family laughter

would disappear with the setting sun

& I would wake up innocent,

as if I had never known anything good

It was starting to happen in small ways

I couldn’t recall the last good day

And then all the flowers poured in

In wreaths and ribbons and bouquets

Thousands and thousands and thousands of flowers

Each dead at the stalk

All dead from the moment they were cut

Every single one dead in their glorious & beautiful selves

Just like the people we lost

In those one hundred days.

.

Day 52

So what if we were all Christian,

Would the media brand it

Christian on Christian violence?

How do the dead declare the part of their identity they were killed for?

.

Day 53

There were echoes if one listened for them

This wasn’t the first time

There were echoes in Acholi

There were echoes in Armenia

There were echoes in the Americas

In Bangladesh

In Bosnia

Cambodia

The Congo

China

There were echoes in Darfur

There were echoes in England

There were echoes in Finland

In Georgia

In Germany

In Hawai’i

In Herero

In India

In Ireland

Japan

Kenya

Latvia

Mongolia

Nakapiripirit

Nairobi

There were echoes in Orange County

There were echoes in Ovambo

In Poland

In Palestine

In Queensland

In Russia

South Africa

Southern Sudan

Tonga

Uganda

Vietnam

Wales

There were echoes in Xenophobic attacks everywhere

Yugoslavia, Zimbabwe.

Where on this planet has not been touched?

The earth palpitates with violence

as if it needs violence

as if violence is a heartbeat – if not here now it’s over there

if it’s not over there now, it’s on its way here

Ours wasn’t the first or the only one;

It was our most painful.

.

Day 54

It is absurd to think that a little girl will forget

how her mother’s hands felt when she used to plait her hair

some tugging, some lining the scalp with an oiled wooden comb

for clean patterns

some cool oil, some warmth when her hands gently repositioned her head like so

sometimes a last pat on the back of her head, sometimes her neck.

Okay, it’s done, you can go out and play now

Absurd that any little girl would forget that – and has.

Day 55

Our lives became both

endless and immediate

There were no guards at the door

There was no door

& the only tax required was a last breath out

One moment you were alive

& the next gone

One minute you were alive

& moments after that you wouldn’t die

your chest gargled endlessly

we were afraid of being heard & then we weren’t

One minute we cared & the next nothing mattered

.

Day 56

Before the maiden voyage

we heard that every water-faring vessel

needed sacrifice

The sacrifice had to be young

The sacrifice had to be blemish free

The sacrifice had to have no dimples, no piercing in the ear

The sacrifice could be male or female

Stay close to home, we were beseeched

Stay close to home lest the sacrifice gatherers came by

We stayed close to home, in those first days

We stayed close to home but the sacrifice gatherer didn’t seem to care for details

They came to harvest all kinds of bodies for a ship whose size has never been measured

.

Day 57

We were halfway to dead when we were reminded

that we were halfway to dead

Hovering, suspecting, tripping

or tiptoeing over the terrain

lest any semblance of confidence betrayed us again.

Ghosts flitted about

attentive to our progress

Chrissie knew

Chrissie could see that having never left ourselves

we were never going to arrive

.

Day 58

Karmic proportions may indicate

that we wanted, expected, earned what we got,

that we wanted it

that we had to go through it

that we had to overcome the trials of life

And you who hasn’t gotten it yet

were and/or are lucky

think again

think again

as long as we’re caught inside the neveragainness of things

we will remain blind to the hundreddaysness of others

Day 59

You want me to talk about what happened

because you say you want to understand

because when you engage with people like me, you say you can make a difference

because you say we all need to make a difference

because all of it, as you say, begins with me telling you what happened

Change the blue dice

Choose the cast

Lock up the hypnotic evil-thought-bearing others

When you engage, you say, you can relieve me of my nightmares

you say you can help me to heal, to look forward without anxiety

When you engage, you say, you will do so with understanding

because you think that at the level of articulation that I have

you say you will have understood

because you will have gotten it, you say,

because you feel me, you say,

because you’re incensed, you say, & will continue to be.

Dear God (or whatever is left)

save us from all the saviours of the world

.

Day 60

I’m coming to understand what seems to be so apparent in nature:

time passes

things change

some live, some die

none escapes this life without an end

I’m coming to understand that there isn’t much more else to it:

time passes

things change

some live, some die

none of us escapes a final end.

.

Day 61

Incredulity is a soft-paced wonder

& in the thick of days

Memory is a slippery thing

What do we remember from those one hundred days?

What happened on the tenth day or night

Might have well happened today, or yesterday

Incredulous is word from an innocent space

It is tepid, blubbery sometimes

because everything can happen and everything did.

. . .

https://www.facebook.com/hashtag/kwibuka20?source=feed_text&story_id=624576410970511

. . . . .

100 Days, 50 Days In: A Poet’s Journey

Posted: May 16, 2014 Filed under: 7 GUEST EDITORS, English, Juliane Okot Bitek | Tags: Wangechi Mutu: 100 days of photographs for The Rwanda Genocide Comments Off on 100 Days, 50 Days In: A Poet’s JourneyI am keenly aware of the paradox in thinking about the halfway point of writing and posting one hundred poems. For those who lived through or must still live through their own hundred days, there is no luxury of knowing a halfway point and yet I’m exhausted by the knowledge that this is only the halfway point.

I’ve come to appreciate the ability to count and depend on the passage of days as a reliable indicator that time passes. I’ve been watching how Wangechi Mutu’s photographs have morphed from very personal, embodied experiences of pain and death to images that radiate loss and loneliness through the passage of time and neglect. And I have looked at the poems I’ve written, thinking about what I can see – and what remains inaccesible to me.

When I wrote the first poem, Day 100, I gathered my visual cues about the landscape from Sometimes in April (directed by Raoul Peck and starring Idris Elba and Carole Karemera) – a collection of delicious greens and mist and rain. I have never been to Rwanda, but this is familiar land, it does not seem very different from places I’ve been, places that are encased with an intense and terrible beauty. I thought about how impossible it would have been to try and read the land for any sign of impending disaster. I imagined what it might have been like to be immersed in those one hundred days, and I also remembered what it was like to be “inside” those endless days of uncertainty during the years of unstable government in Uganda when I was a teenager during the eighties. I thought about the people who lived through the war in northern Uganda (1986-2007) and those who were taken by the Lord’s Resistance Army, many who never returned.

And the ridiculousness of measured time when the experience of those days plays out like a rubber band – stretching, snapping, stretching and snapping, and every time differently. I’ve also been thinking about how much these 100 Days have a way of taking Memory of those days beyond the realm of public commemoration: speeches, flowers, and eternal flames. 100 Days of poems is not an accurate depiction for anyone to depend on, but they are a way to enter into the private space not reflected by events outside. They have to be an imperfect collection; they’re barely edited and most of the time completely unchecked – emotionally. There’s been no time to craft these poems, to practice an art; this is raw expression. These are what I imagine 100 Days would sound like, if I could have a conversation with someone who has journeyed twenty years without much to celebrate. What must it mean to look forward when all that provided the impetus for your future remains deeply embedded in the past?

Mid-May: almost halfway through a hundred days and I check in with myself. I feel stretched, vulnerable, worn out. I must post a poem every day and yet I cannot write a poem every day – so I write ahead when I can. I feel vulnerable to the voices that can prevent me from sleeping and are an insistent whisper in my head during the day. I read through the poems already posted and look for cues and patterns but it’s like looking at my back in the mirror. A friend tells me that anger becomes apparent in Day 59. Do betrayal and anger occupy different spaces in these poems? I don’t know how to read these poems but I know what I carry.

Twenty years after the genocide in Rwanda is twenty years after the ANC won elections in South Africa; there is mourning and celebration at the same time. And gratitude for having come through – how can there not be? But what do we do with the persistent heartbroken-ness? How do you remember the worst time of your life after twenty years? War persists. A powerful undercurrent of apathy buoys others who understand that war “over there” has nothing to do with life “over here”. Some things get done through obligation and sometimes pity, without any acknowledgement of the connectedness that binds us all. War is a contagion; none of us is immune. As long as commemorations continue to focus on the might and muscle of the winners, there may never be enough space to hold dialogue with those who are yet to heal from the wounds of war.

Juliane Okot Bitek

May 16th, 2014

. . . . .

The Rwanda Genocide, twenty years later: 100 Days of photographs + poems by Wangechi Mutu and Juliane Okot Bitek

Posted: May 5, 2014 Filed under: 7 GUEST EDITORS, English, Juliane Okot Bitek | Tags: Wangechi Mutu: 100 days of photographs for The Rwanda Genocide Comments Off on The Rwanda Genocide, twenty years later: 100 Days of photographs + poems by Wangechi Mutu and Juliane Okot Bitek

Juliane Okot Bitek

100 Days: a poetic response to Wangechi Mutu’s #Kwibuka20#100 Days

. . .

Day 62

Unless you believe in the eye of the needle

This kind of poverty will never be about material

It won’t be about ragged clothing

or mud huts with broken walls

or river blindess

or murram roads

or bad humoured fields that hoard curses

There won’t be a harvest this year or next

This isn’t the poverty of sleep

or for that matter, dreams

This is my deep loss, my poverty:

He will never touch my hand again

He will never touch my hand

.

Day 63

Walter says life is hard

He says that there is nothing we can do about it

Walter says I have to be happy to be alive

Walter says to be alive is better than being dead

Be happy, Walter says

Be happy to be alive

If being dead is not all that it’s cracked up to be

Then what was that all that rush about?

For my happiness?

.

Day 64

There have been three so far

Three men who walk with your gait

Who turn, head first, the way you used to

Walk like you did, sauntering like a cat

Laugh with your laugh

Flick the wrist the way you used to

just before you pointed your finger to make a point

All three men wore you face for a moment

Lighted mine up

You mean to say?

And then you were gone again

and the men were just ordinary men

doing ordinary things

Three imposters

Three who acquiesced to your tricks of reminding me

that you used to be by me

.

Day 65

Often times I want to become words

I want to inhabit forgetting as a state of being

Other times I think that if we wore a cloak of silence

Then our invisibility would not be seen as repair

or a sign that everything was good

The problem of becoming silence is that silence doesn’t exist

It wasn’t ever completely silent

Nothing stopped to pay attention

Nature chattered on, busy with life cycling

And subsumed us into the process

.

Day 66

Sometimes I want to melt into the earth

I want to imagine that some time in the future

Children will run over the soil that I’ve become

.

Day 67

Some days

I want to stare at the sky

Perhaps I can learn something, anything

Some days I think about how important the sky has become

I think about it so much and in so doing, I make it exist

I make the sky an endless and expansive backdrop of blue

If there was a sky, how could it witness what it did

& maintain that calm hue?

.

Day 68

There’s no denying that these haunted days

Are not necessarily days of grey

There are flowers everywhere

Beauty is always undeniable

These hundred days are haunted days not grey ones

These hundred days are filled with ghosted moments

just like every day

.

Day 69

The world turns as it does

Spinning on its own axis and then around the sun.

Perhaps this galaxy is also spinning around something bigger

Perhaps all the worlds spin in order to avoid dealing with the numbers:

Fourteen

Three

All of them

Six from my in-laws

and all of my siblings, parents and their children

Twenty seven

Thirteen

Everyone

Everyone

All of them

Six

Nine

Twelve

My husband and all my children – seven in all

Two

Nineteen

I don’t know

I can’t count anymore

Nobody came back

I don’t know if they ran away to safety or

If they’re just all gone

.

Day 70

Too close for comfort when everyone around looks like you.

Too close when they speak your language

Too close when you’re from the same house

Same meal at the table

Same sofa

Same containment of the heart

We became other people

We were them, those ones

And in being slaughtered and reported as slaughtered

We lost any claim to intimacy or self

Even animals don’t commit slaughter

Day 71

Who says alas in the presence of betrayal?

Who dizzies away, swirling skirts & claims of nausea

Alas, alas all the hand wringing!

It shouldn’t have been this way?

It shouldn’t?

It shouldn’t have been

forms the dregs from the past

It shouldn’t have been this way

Would it have been better that this was lobbed at your head?

Would it have been better if yours was the stuff of our nightmares?

.

Day 72

The difference between the top screw

and the bottom screw is this: direction

We are squeezed in by the past and the present

Everything is relative, they say

God and religion and offer escape from the screw

in the name of forgiveness, reconciliation & clean heartedness

Be like Jesus, forgive

Be like Jesus, remember to pray and to pay taxes

Be like Jesus, wear robes,

Have your first cousin shout in the streets about the second coming of yourself

Be like Jesus, hang out with prostitutes – love the sinner and all that

Above all be like Jesus and demand an answer in the moment of your cross

Why, God, have you forsaken us?

Day 73

There are witness stones along all roads

Between Jinja and Kampala

The road to Damascus

The roads leading to Kigali or Rome

Even the road less travelled

The old majesty of Kenyatta Avenue

Khao San, Via Dolorosa

And the Sea to Sky highway

where every few steps they say

is marked by the blood

of a foreign and indentured worker

Did you ever know stones in the road to scream?

They did in those days, you know

They still do sometimes

.

Day 74

In thirty- nine days there will be no more hindsight for sure

Today already there’s hardly any

No foresight

No insight

No encryption

In thirty-nine days, like today

There will be the same dullness about

The same powdery taste to everything

The same floaty feeling — the eerie pull to something beyond now

Ants keep busy

They have figured out that life is for living

And death is for dying

There is no space for those of us

Who are not dead and have yet to be resurrected

.

Day 75

There is evidence that this was a conspiracy of silence:

the insistence of green grass

the luminosity of a full moon

the leathered skin of the dead

the smile of skulls

flowers

the roar of the rushing river

endless, endless hills

If there was a shocked response

If this was an unnatural state of being

If this was a never, ever kind of situation

Why didn’t the world turn upside down?

. . .

https://www.facebook.com/hashtag/kwibuka20?source=feed_text&story_id=624576410970511

.

Days 76 – 100:

https://zocalopoets.com/2014/05/01/the-rwanda-genocide-twenty-years-later-100-days-of-photographs-poems-by-wangechi-mutu-and-juliane-okot-bitek/