Kleopatra Lymperi: “Cuando Vendrás En Tu Reino…”

Posted: January 25, 2016 Filed under: English, Greek, Kleopatra Lymperis, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: Greek women poets, Poetisas griegas Comments Off on Kleopatra Lymperi: “Cuando Vendrás En Tu Reino…”Η Kλεοπάτρα Λυμπέρη

ΟΤΑΝ ΕΛΘΕΙΣ ΕΝ ΤΗ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΙΑ ΣΟΥ

.

Ποίημα, σε λίγο θα φύγεις, θα πάρεις

τους δρόμους σαν σκύλος

σαν ντάλια κομμένη – τι θα έχω τότε,

ποιός θα είμαι; σε τι κατοικίες θα πλαγιάζω

χωρίς φαϊ, χωρίς, νερό χωρίς κορμί;

.

Ποίημα, μου ρίχνεις τόσους σκοτωμένους

να με σκεπάσουν όλα τα υπαρκτά

και τα κατεβατά της ερήμου

όλοι οι άνεμοι, οι σχηματισμοί πτηνών και οι

φωλιές τους, οι θύελλες οι αισθηματικές τους.

.

Ποίημα, συ ο παρών, ο ενεδρεύων

σε κάμπους πίσω από μάτια και μυαλά,

σε όλα τα λόγια που με διώχνουν από τη

φωλιά, σε οράματα που φτύνουν στο στόμα μου

όπως οι σαμάνοι

μα και σε ουρλιαχτά των Άλπεων

(τόσο πολύ χιόνι μαζεύεται όταν λείπεις)

.

Ποίημα, ποιος είσαι; Ποιοι είμαστε όλοι οι

κρυμμένοι στον έναν αυτόν που τώρα μιλά;

Αν γίνεις ο ρυθμός, το σχήμα, το ρίγος

το στήθος των φτερωτών ζηλωτών των γλωσσών

σαν λαμπάδα του Πάσχα θ’ ανάψεις

σαν έρως του Ενός

-μνήσθητί μου, Ποίημα, όταν έρθεις εν τη

βασιλεία σου στο σπίτι του Κανενός.

. . .

Kleopatra Lymperi (Chalkis, Greece)

When Thou Comest Into Thy Kingdom

.

Poem, soon you will leave, you will roam

the streets like a dog,

like a cut dahlia – what will I have then?

who will I be? What home will I sleep in

with no food, no water, no body?

.

Poem, you throw me so many dead bodies

so that I am covered by all existence,

and the densely written pages of the desert:

all the winds, the bird formations and

their nests, their emotional tempests.

.

Poem, you, the omnipresent, the prowler

in lowlands behind bosoms and brains,

in all the words that cast me out of the

nest, in visions spitting into my mouth

like shamans,

but also in Alpine howlings

(that much snow piles up when you’re gone).

.

Poem, who are you? Who are we all,

hidden inside the one who is speaking now?

If you become the rhythm, the form, the tremor,

the bosom of the winged zealots of the languages,

you will light up like an Easter candle,

like Eros of the One.

Poem, remember me when thou comest into thy

kingdom, the house of No one.

. . .

Translation from the Greek original © Tatiana Sergiadi

. . .

Kleopatra Lymperis (Chalkis, Grecia)

Cuando Vendrás En Tu Reino…

.

Poema,

te irás pronto, vagabundearás las calles – como un perro, como una dalia cortada.

Pues ¿qué tendré, y quién seré?

¿En cuál hogar dormiré – sin alimento, sin agua, sin cuerpo?

.

Poema,

me tiras tantos cadáveres pues estoy cubierto por toda la existencia

y las páginas del desierto, densamente escritas; y todos los vientos,

las formaciones de pájaros y sus nidos, y sus tempestades emotivas.

.

Poema

– tú –

el merodeador omnipresente en las tierras bajas detrás de bustos y sesos;

estás en todas las palabras que me lanzan del nido;

y en las visiones que escupen en mi boca, como hacen los chamanes;

estás presente también en los aullidos alpinos

(sí, tanta nieve amontona cuando estés ausente).

.

Poema

– ¿quién eres tú? – ¿quién somos nosotros, todos, escondidos dentro del uno que habla ahora?

Si te vuelvas el ritmo-la forma-el temblor-el pecho de los fanáticos alados de los idiomas,

te iluminarás como una vela de Pascua, o como Eros del Uno.

Poema, recuérdame cuando vendrás en tu reino – en tu mansión de Nadie.

. . .

Versión español – de la traducción inglés del griego: Alexander Best

. . .

Kleopatra Lymperi estudió la música y la pintura en Atenas. Además de su poesía, tiene una obra considerable de traducciones: poemas de Dickinson, Mailer, Pound, Plath y otros. Ha contribuido al periódico Eleutherotypia y al revista Poeticanet.

.

Kleopatra Lymperi studied music and painting in Athens, at the Conservatory and the School of Fine Arts, respectively. As well as writing poetry, she has been a busy translator: poems of Dickinson, Mailer, Pound, Plath and others. She has collaborated on the newspaper Eleutherotypia and writes essays and book reviews for the e-magazine Poeticanet.

. . . . .

Tasoula Karageorgiou: “La tortuga de Kerameikos”

Posted: January 25, 2016 Filed under: English, Greek, Spanish, Tasoula Karageorgiou, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: Greek women poets, Poetisas griegas Comments Off on Tasoula Karageorgiou: “La tortuga de Kerameikos”Η Τασούλα Καραγεωργίου

Η ΧΕΛΩΝΑ ΤΟΥ ΚΕΡΑΜΕΙΚΟΥ

.

Ίσως φανείτε τυχεροί, όπως κι εγώ,

εάν βρεθείτε Απρίλη μήνα στον Κεραμεικό,

ίσως τη δείτε ξαφνικά

να σέρνεται λικνιστικά

μες στα χλωρά τριφύλλια

.

Κι αν γύρω σας ακινητούν οι επιτύμβιας στήλες

κι έφιππος ο Δεξίλεως γλεντάει τον θάνατό του,

ακόμα κι αν σας συγκινεί μονάχα η τέχνη της σιωπής,

δώσετε λίγη προσοχή

στο θαύμα που ζωγράφισε ὁ Θεός πάνω στο καύκαλό της,

μα πιο πολύ,

στο πείσμα της αδιάφορη να οδεύει προς τους τάφους.

.

(Χελώνη η ελληνική,

πατρίδα μου, βραδύ γλυπτό, που προσπερνάει τον Άδη.)

. . .

Tasoula Karageorgiou (born 1954, Alexandria, Egypt)

The Kerameikos Tortoise

.

If you are lucky, like me,

and find yourselves in April among the graves of Kerameikos,

all of a sudden you may see her

swishing and swaying

through the green shamrocks.

.

And if the grave steles around you stay still

and if Dexileos on his horse revels in his death,

even if you are moved by the art of silence only,

pay a little attention to

the miracle God painted on her carapace,

yet even more

her stubborn, indifferent crawling to the graves.

.

<Tortoise the Greek,

homeland of mine, tardy sculpture, passing by Hades.>

. . .

Translation from the Greek original © Vasso Oikonomidou

. . .

Tasoula Karageorgiou (n. 1954, Alexandria, Egipto)

La tortuga de Kerameikos

.

Si ustedes tienen suerte – como yo –

y, en abril, se encuentran entre las tumbas de Kerameikos,

repentinamente le vieren a ella,

dando chasquidos y bamboleándose

a través de los tréboles verdes.

.

Y si las estelas de tumbas alrededor de ustedes no se mueven,

y si Dexileos en su caballo se deleita en su muerte,

y aun si estén conmovidos solamente por el arte de silencio,

presten atención al milagro que Dios pintó en su carapazón

– pero, aun más,

sus pasos tan lentos, tercos y indiferentes, hacia las tumbas.

.

< Galápago el griego…

patria mía, escultura demorada, pasando por Hades… >

. . .

Kerameikos (El Cerámico) es el nombre de un cementerio/camposanto antiguo de Atenas, no lejos del Acrópolis.

. . .

Versión español – de la traducción inglés del griego: Alexander Best

. . .

Born in Alexandria, Egypt, Tasoula Karageorgiou has worked as a secondary school teacher in Greece since 1981. She holds a PhD in philology. She has also published a half a dozen poetry collections, and since 2007 has taught a Modern Greek Poetry class in the Poetry Lab at Takis Sinopoulos Foundation.

.

Nativa de Alexandria, Egipto, Tasoula Karageorgiou ha enseñado en las escuelas secundarias de Grecia desde 1981. Y desde 2007 ha dirigido una clase sobre la poesía moderna en la Fundación Takis Sinopoulos.

. . . . .

Cloe Kutsubeli: “Mi familia”

Posted: January 25, 2016 Filed under: Cloe Kutsubeli, English, Greek, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: Greek women poets, Poetisas griegas Comments Off on Cloe Kutsubeli: “Mi familia”Η ΟΙΚΟΓΕΝΕΙΑ ΜΟΥ

.

Ο μπαμπάς μου φορούσε πάντα αδιάβροχο

και κρατούσε μια γκρίζα ομπρέλα για τον ήλιο,

αγαπούσε γυναίκες κι όλο έφευγε,

κι έπαιζε σε ταινίες κατασκόπων

τον ρόλο της κλειδαριάς στην πόρτα

ή του ανοιχτού παράθυρου

στη μέση μιας ερήμου.

Πολύ του άρεσαν πάντα τα καπέλα.

Η μαμά μου φορούσε όμορφα καπέλα.

με ζωντανά ακέφαλα παγόνια να μαλώνουν.

Ο αδελφός μου ήταν κύκνος,

κρυστάλλινος και διάφανος,

σε χίλιες δυο μεριές του ραγισμένος

και τόσο, μα τόσο ανυπεράσπιστος,

που πάντα έμπαινα στον πειρασμό

να τον ρίξω κάτω για να σπάσει.

Κι εγώ ήμουν αξιολάτρευτη,

στα άσπρα πάντοτε ντυμένη,

έτρωγα κέικ από μοναξιά,

σ’ ένα ετοιμόρροπο, καθόμουνα μπαλκόνι.

Υστερα η μαμά χάθηκε μες στον καθρέφτη,

ο μπαμπάς αγάπησε ένα πουλί και πέταξε,

ο αδελφός μου παντρεύτηκε την Νύχτα

και το μπαλκόνι μου κατέρρευσε στην θάλασσα.

Κι από όλη την οικογένειά μου

απόμεινε μόνο ένα άλμπουμ με σκιές

να κυνηγούν ατέρμονα η μια την άλλη μες στη νύχτα.

. . .

Cloe Kutsubeli (born 1962, Thessaloniki)

My Family

.

My father always wore a raincoat

and held a grey umbrella for the sun;

he was fond of women and always left.

He liked to play in spy films,

pretending to be a lock

or an open window in the middle of the desert.

He always liked hats.

My mother wore beautiful hats,

with headless peacocks fighting.

My brother was a swan,

crystal and transparent,

cracked in a thousand pieces,

and so very defenceless

that I was tempted

to knock him down only to see him break.

And I was adorable…

always dressed in white,

eating cake out of loneliness,

sitting on a rickety balcony.

Then: mother disappeared in a mirror,

father fell in love with a bird and flew away,

my brother took Night as his wife,

and my balcony collapsed into the sea.

And what remains of my family

is a photo album with shadows

who chase each other endlessly

all through the night.

. . .

Cloe Kutsubeli (n. 1962)

Mi familia

.

Siempre llevaba un impermeable, mi padre;

también un paraguas gris para el sol.

Estaba afecto a las mujeres y siempre partió.

Le gustaba jugar un rol en películas sobre espías,

simulando ser una cerradura

o una ventana abierta en el medio del desierto.

Y siempre le agradan gorros.

Mi madre llevaba puesto unos bellos gorros,

con pavos reales (sin cabezas) peleandos.

Mi hermano fue un cisne,

de cristal y transparente,

rajado en mil piezas;

él era tan indefenso que

estuve tentada de tumbarle para mirarle quebrando.

Y yo era adorable, siempre vestida de blanco,

comiendo pasteles a causa de mi aislamiento

mientras me sentaba en un balcón tambaleante.

Más adelante, mi madre desapareció dentro de un espejo;

mi padre se enamoró con un pájaro pues se echó a volar;

mi hermano aceptó como su esposa la Noche;

también mi balcón se derrumbó en el mar.

Y lo que queda de mi familia es un álbum fotográfico

con sombras que persiguen entre ellas,

sin parar, toda la noche.

. . .

Versión español – de la traducción del griego: Alexander Best

. . .

Cloe Kutsubeli es una poeta, novelista y dramaturga.

Nació en Salónica.

.

Cloe Kutsubeli is a poet, novelist, and playwright. She has also written books for children.

. . . . .

Kiki Dimoula: Ο πληθυντικός αριθμός / Το άλλοθι : dos poemas griegos en español

Posted: January 11, 2016 Filed under: Greek, Kiki Dimoula, Spanish | Tags: Poetisas griegas Comments Off on Kiki Dimoula: Ο πληθυντικός αριθμός / Το άλλοθι : dos poemas griegos en español

Ο πληθυντικός αριθμός

.

Ο έρωτας,

όνομα ουσιαστικόν

πολύ ουσιαστικόν,

ενικού αριθμού,

γένους ούτε θηλυκού ούτε αρσενικού,

γένους ανυπεράσπιστου.

Πληθυντικός αριθμός

οι ανυπεράσπιστοι έρωτες.

.

Ο φόβος,

όνομα ουσιαστικόν,

στην αρχή ενικός αριθμός

και μετά πληθυντικός:

οι φόβοι.

Οι φόβοι

για όλα από δω και πέρα.

.

Η μνήμη,

κύριο όνομα των θλίψεων,

ενικού αριθμού,

μόνον ενικού αριθμού

και άκλιτη.

Η μνήμη, η μνήμη, η μνήμη.

.

Η νύχτα,

όνομα ουσιαστικόν,

γένους θηλυκού,

ενικός αριθμός.

Πληθυντικός αριθμός

οι νύχτες.

Οι νύχτες από δω και πέρα.

. . .

Kiki Dimoula (n. 1931, Atenas, Grecia)

El número plural

.

El amor,

nombre sustantivo,

muy sustantivo,

número singular,

género ni femenino ni masculino,

género desvalido.

Número plural:

los amores desvalidos.

.

El miedo,

nombre sustantivo,

al principio número singular

y luego plural:

los miedos.

Los miedos

por todo a partir de ahora.

.

La memoria,

nombre propio de los pesares,

número singular,

sólo número singular

e indeclinable.

La memoria, la memoria, la memoria.

.

La noche,

nombre sustantivo,

género femenino,

número singular.

Número plural:

las noches.

Las noches de ahora en adelante.

. . .

Del poemario Poemas (1998)

. . .

Το άλλοθι

.

Kάθε που σ’ επισκέπτομαι

μονάχα ο καιρός που μεσολάβησε

από τη μια φορά στην άλλη έχει αλλάξει.

Kατά τα άλλα, όπως πάντα

τρέχει από τα μάτια μου ποτάμι

θολό το χαραγμένο όνομά σου

– ανάδοχος της μικρούλας παύλας

ανάμεσα στις δυο χρονολογίες

να μη νομίζει ο κόσμος ότι πέθανε

αβάπτιστη η διάρκεια της ζωής σου.

Eν συνεχεία σκουπίζω τις μαραμένες

κουτσουλιές των λουλουδιών προσθέτοντας

λίγο κοκκινόχωμα εκεί που ετέθη μαύρο

κι αλλάζω τέλος το ποτήρι στο καντήλι

με άλλο καθαρό που φέρνω.

.

Aμέσως μόλις γυρίσω σπίτι

σχολαστικά θα πλύνω το λερό

απολυμαίνοντας με χλωρίνες

και καυστικούς αφρούς φρίκης που βγάζω

καθώς αναταράζομαι δυνατά.

Mε γάντια πάντα και κρατώντας το σώμα μου

σε μεγάλη απόσταση από το νιπτηράκι

να μη με πιτσιλάνε τα νεκρά νερά.

Mε σύρμα σκληρής αποστροφής ξύνω

τα κολλημένα λίπη στου ποτηριού τα χείλη

και στον ουρανίσκο της σβησμένης φλόγας

ενώ οργή συνθλίβει τον παράνομο περίπατο

κάποιου σαλιγκαριού, καταπατητή

της γείτονος ακινησίας.

.

Ξεπλένω μετά ξεπλένω με ζεματιστή μανία

κοχλάζει η προσπάθεια να φέρω το ποτήρι στην πρώτη

τη χαρούμενη τη φυσική του χρήση

την ξεδιψαστική.

Kαι γίνεται πια ολοκάθαρο, λάμπει

το πόσο υποχόνδρια δε θέλω να πεθάνω

.

ακριβέ μου – πάρτο κι αλλιώς:

πότε δε φοβότανε το θάνατο η αγάπη…

. . .

Kiki Dimoula

La coartada

.

Cada vez que te visito

sólo el tiempo transcurrido

de una vez a otra ha cambiado.

Por lo demás, como siempre

se desliza desde mis ojos como un río

turbio tu nombre grabado

—padrino del guión pequeñín

entre las dos fechas,

no vaya a pensar la gente que ha muerto

sin bautizar la duración de tu vida.

A continuación limpio las mustias

cagaditas de las flores añadiendo

algo de arcilla roja donde se ha depositado negra

y le cambio, finalmente, el vaso a la lamparilla

por otro limpio que traigo.

.

Nada más volver a casa

a conciencia lavaré el sucio

desinfectando con lejías

y cáusticas espumas de espanto que echo

cuando me agito con fuerza.

Con guantes siempre y manteniendo mi cuerpo

a gran distancia del pequeño lavabo

para que no me salpiquen las aguas muertas.

Con estropajo metálico de dura aversión rasco

la grasa pegada en los labios del vaso

y en el paladar de la apagada llama

mientras la ira aplasta el ilegal paseo

de algún caracol, usurpador

de la inmovilidad vecina.

.

Enjuago luego enjuago con escaldante furia

bulle mi intento de volver el vaso a su primer

su alegre su natural uso

el de saciar la sed.

Y queda ya del todo limpio, reluce

ese mi afán hipocondríaco de no querer morir

.

querido mío, míralo de otro modo:

¿cuándo no ha temido a la muerte el amor?

.

Del poemario De un minuto juntos (1998)

. . .

Traducciones del griego: © 2009 Raquel Pérez Mena (Profesora del Instituto de Idiomas de la Universidad de Sevilla)

. . . . .

Melissanthi (Μελισσάνθη): “Satyricon” em português

Posted: January 6, 2016 Filed under: Greek, Melissanthi, Portuguese Comments Off on Melissanthi (Μελισσάνθη): “Satyricon” em português

Melissanthi (~1907-1991, Atenas, Grécia)

Satyricon

.

Perguntaram à baleia

se queria morrer

para transformar-se numa lépida

criatura do ar.

Ela respondeu: “Jamais!”

Queria mesmo era ficar para sempre

na segurança do seu líquido elemento,

uma baleia apenas, nada mais.

“Uma baleia por toda a eternidade! – exclamou alguém.

– Mas isso é monstruoso.

Se ao menos fosse, como eu,

um hipopótamo!”

. . .

Tradução: José Paulo (1986)

. . .

Grego original:

Σατιρικόν

Ρώτησαν τη φάλαινα

αν θα ΄θελε να πεθάνει

και να μεταμορφωθεί

σ΄ ανάλαφρο πλάσμα του αέρα

κι απάντησε· «Όχι, ποτέ!»

Ναι, θα ΄θελε για πάντοτε να μείνει

μέσα στη βεβαιότητα του υγρού στοιχείου

μια φάλαινα και τίποτα άλλο.

«Φάλαινα στην αιωνιότητα! – φώναξε κάποιος –

Μ΄ αυτό είναι μια τερατωδία

Να ΄ταν τουλάχιστον, καθώς εγώ

ένας ιπποπόταμος!»

. . . . .

Zoe Karelli: Άνθρωπος / “Woman Man”

Posted: January 4, 2016 Filed under: English, Greek, Zoe Karelli | Tags: Greek women poets Comments Off on Zoe Karelli: Άνθρωπος / “Woman Man”

Zoe Karelli (1901-1998, born Thessaloniki, Greece)

Άνθρωπος

.

Εγώ γυναίκα, η άνθρωπος,

ζητούσα το πρόσωπό Σου πάντοτε,

ήταν ως τώρα του ανδρός

και δεν μπορώ αλλιώς να το γνωρίσω.

Ποιός είναι και πώς

πιο πολύ μονάχος,

παράφορα, απελπισμένα μονάχος,

τώρα, εγώ ή εκείνος;

Πίστεψα πως υπάρχω, θα υπάρχω,

όμως πότε υπήρχα δίχως του

και τώρα,

πώς στέκομαι, σε ποιό φως,

ποιός είναι ο δικός μου ακόμα καημός;

Ω, πόσο διπλά υποφέρω,

χάνομαι διαρκώς,

όταν Εσύ οδηγός μου δεν είσαι.

Πώς θα δω το πρόσωπό μου,

την ψυχή μου πώς θα παραδεχτώ,

όταν τόσο παλεύω

και δεν μπορώ ν΄αρμοστώ.

«Ότι δια σου αρμόζεται

γυνή τω ανδρί.»

Δεν φαίνεται ακόμα το τραγικό

του απρόσωπου, ούτε κι εγώ

δεν μπορώ να το φανταστώ ακόμα, ακόμα.

Τι θα γίνει που τόσο καλά,

τόσο πολλά ξέρω και γνωρίζω καλύτερα,

πως απ΄το πλευρό του δεν μ΄έβγαλες.

Και λέω πως είμαι ακέριος άνθρωπος

και μόνος. Δίχως του δεν εγινόμουν

και τώρα είμαι και μπορώ

κι είμαστε ζεύγος χωρισμένο, εκείνος

κι εγώ έχω το δικό μου φως,

εγώ ποτέ, σελήνη,

είπα πως δεν θα βαστώ απ΄τον ήλιο

κι έχω τόσην υπερηφάνεια

που πάω τη δική του να φτάσω

και να ξεπεράσω, εγώ,

που τώρα μαθαίνομαι και πλήρως

μαθαίνω πως θέλω σ΄εκείνον ν΄αντισταθώ

και δεν θέλω από κείνον τίποτα

να δεχτώ και δε θέλω να περιμένω.

Δεν κλαίω, ούτε τραγούδι ψάλλω.

Μα γίνεται πιο οδυνηρό το δικό μου

ξέσκισμα που ΄τοιμάζω,

για να γνωρίσω τον κόσμο δι΄εμού,

για να πω το λόγο δικό μου,

εγώ που ως τώρα υπήρξα

για να θαυμάζω, να σέβομαι και ν΄αγαπώ,

εγώ πια δεν του ανήκω

και πρέπει μονάχη να είμαι,

εγώ, η άνθρωπος.

. . .

Woman Man

.

I, a woman man,

sought Your face always.

It was til now a man’s,

and I cannot know it otherwise.

Who is more alone now,

wildly, hopelessly alone?

Him or me

and in what way?

I thought I existed,

would keep on existing,

but I never did, except through him.

And now

how can I stand on my own, in what light,

and what is this sadness that is not his?

Oh, how I suffer doubly,

losing myself again and again,

when You, my leader are no longer there.

How can I see my face,

how can I accept my soul,

when I struggle so

and do not fit in?

Because God made woman

in the image of man.

The tragic sense of the impersonal

isn’t clear yet,

nor can I imagine it.

What will happen now that I know

and understand so well

that you did not pull me

from his side?

And yet I call myself a complete person

on my own. Without him I was nothing

and now I am and can become anything,

but we are a separate pair, him

and me, with my own light,

not a moon to his sun,

and I am so proud

to reach his heights

and surpass myself, I

who have now learned

to stand up to him

and not ask for anything,

to accept and no longer wait.

I do not cry or sing,

but the break I must make

is the cruelest

to know the world through myself

to speak my own words.

I who until now have existed

to worship, respect and love.

I no longer belong to him,

I exist on my own,

a human being.

.

Translation from the Greek: Karen Van Dyck

. . .

Zoe Karelli was the pen-name of Chrysoula Argyriadou (née Pentziki), born 1901 in Thessaloniki. Her poems face the hard dilemmas of life yet may display hope and optimism as well. She is regarded as a pioneering feminist in her native Greece. In 1982 Karelli was the first woman of letters to be elected to the Academy of Athens and was recipient of the Ouranis Award for her collected works (including plays and essays) in 1978. She is best known for her 1957 poem – above – which is difficult to translate because of her use of the feminine article with the Greek word for “mankind”. The translator here has chosen in English the hybrid phrase “Woman Man”.

. . . . .

Pro-Sex Poems of Love and Desire: the exquisite verse of Constantine P. Cavafy

Posted: December 5, 2014 Filed under: English, Greek, Konstantin Kavafis Comments Off on Pro-Sex Poems of Love and Desire: the exquisite verse of Constantine P. CavafyC.P. Cavafy (Greek poet from Alexandria, Egypt: 1863-1933)

Body, Remember

.

Body, remember not only how much you were loved,

not only the beds you lay on,

but also those desires that glowed openly

in eyes that looked at you,

trembled for you in the voices—

only some chance obstacle frustrated them.

Now that it’s all finally in the past,

it seems almost as if you gave yourself

to those desires too—how they glowed,

remember, in eyes that looked at you,

remember, body, how they trembled for you in those voices.

.

Body, Remember – in the original Greek:

Θυμήσου, Σώμα…

.

Σώμα, θυμήσου όχι μόνο το πόσο αγαπήθηκες,

όχι μονάχα τα κρεββάτια όπου πλάγιασες,

αλλά κ’ εκείνες τες επιθυμίες που για σένα

γυάλιζαν μες στα μάτια φανερά,

κ’ ετρέμανε μες στην φωνή — και κάποιο

τυχαίον εμπόδιο τες ματαίωσε.

Τώρα που είναι όλα πια μέσα στο παρελθόν,

μοιάζει σχεδόν και στες επιθυμίες

εκείνες σαν να δόθηκες — πώς γυάλιζαν,

θυμήσου, μες στα μάτια που σε κύτταζαν·

πώς έτρεμαν μες στην φωνή, για σε, θυμήσου, σώμα.

. . .

He had come there to read…

.

He had come there to read. Two or three books lie open,

books by historians, by poets.

But he read for barely ten minutes,

then gave it up, falling half asleep on the sofa.

He’s completely devoted to books—

but he’s twenty-three, and very good-looking;

and this afternoon Eros entered

his ideal flesh, his lips.

An erotic warmth entered

his completely lovely flesh—

with no ridiculous shame about the form the pleasure took….

.

In the original Greek:

Ήλθε για να διαβάσει —

.

Ήλθε για να διαβάσει. Είν’ ανοιχτά

δυο, τρία βιβλία· ιστορικοί και ποιηταί.

Μα μόλις διάβασε δέκα λεπτά,

και τα παραίτησε. Στον καναπέ

μισοκοιμάται. Aνήκει πλήρως στα βιβλία —

αλλ’ είναι είκοσι τριώ ετών, κ’ είν’ έμορφος πολύ·

και σήμερα το απόγευμα πέρασ’ ο έρως

στην ιδεώδη σάρκα του, στα χείλη.

Στη σάρκα του που είναι όλο καλλονή

η θέρμη πέρασεν η ερωτική·

χωρίς αστείαν αιδώ για την μορφή της απολαύσεως …..

. . .

He asked about the quality

.

He left the office where he’d taken up

a trivial, poorly paid job

(eight pounds a month, including bonuses)—

left at the end of the dreary work

that kept him bent all afternoon,

came out at seven and walked off slowly,

idling his way down the street. Good-looking;

and interesting: showing as he did that he’d reached

his full sensual capacity.

He’d turned twenty-nine the month before.

He idled his way down the main street

and the poor side-streets that led to his home.

Passing in front of a small shop

that sold cheap and flimsy things for workers,

he saw a face inside there, saw a figure

that compelled him to go in, and he pretended

he wanted to look at some colored handkerchiefs.

He asked about the quality of the handkerchiefs

and how much they cost, his voice choking,

almost silenced by desire.

And the answers came back the same way,

distracted, the voice hushed,

offering hidden consent.

They kept on talking about the merchandise—but

the only purpose: that their hands might touch

over the handkerchiefs, that their faces, their lips,

might move close together as though by chance—

a moment’s meeting of limb against limb.

Quickly, secretly, so the shopowner sitting at the back

wouldn’t realize what was going on.

.

Ρωτούσε για την ποιότητα—

.

Aπ’ το γραφείον όπου είχε προσληφθεί

σε θέσι ασήμαντη και φθηνοπληρωμένη

(ώς οκτώ λίρες το μηνιάτικό του: με τα τυχερά)

βγήκε σαν τέλεψεν η έρημη δουλειά

που όλο το απόγευμα ήταν σκυμένος:

βγήκεν η ώρα επτά, και περπατούσε αργά

και χάζευε στον δρόμο.— Έμορφος·

κ’ ενδιαφέρων: έτσι που έδειχνε φθασμένος

στην πλήρη του αισθησιακήν απόδοσι.

Τα είκοσι εννιά, τον περασμένο μήνα τα είχε κλείσει.

Εχάζευε στον δρόμο, και στες πτωχικές

παρόδους που οδηγούσαν προς την κατοικία του.

Περνώντας εμπρός σ’ ένα μαγαζί μικρό

όπου πουλιούνταν κάτι πράγματα

ψεύτικα και φθηνά για εργατικούς,

είδ’ εκεί μέσα ένα πρόσωπο, είδε μια μορφή

όπου τον έσπρωξαν και εισήλθε, και ζητούσε

τάχα να δει χρωματιστά μαντήλια.

Pωτούσε για την ποιότητα των μαντηλιών

και τι κοστίζουν με φωνή πνιγμένη,

σχεδόν σβυσμένη απ’ την επιθυμία.

Κι ανάλογα ήλθαν η απαντήσεις,

αφηρημένες, με φωνή χαμηλωμένη,

με υπολανθάνουσα συναίνεσι.

Όλο και κάτι έλεγαν για την πραγμάτεια — αλλά

μόνος σκοπός: τα χέρια των ν’ αγγίζουν

επάνω απ’ τα μαντήλια· να πλησιάζουν

τα πρόσωπα, τα χείλη σαν τυχαίως·

μια στιγμιαία στα μέλη επαφή.

Γρήγορα και κρυφά, για να μη νοιώσει

ο καταστηματάρχης που στο βάθος κάθονταν.

. . .

Days of 1896

.

He became completely degraded. His erotic tendency,

condemned and strictly forbidden

(but innate for all that), was the cause of it:

society was totally prudish.

He gradually lost what little money he had,

then his social standing, then his reputation.

Nearly thirty, he had never worked a full year—

at least not at a legitimate job.

Sometimes he earned enough to get by

acting the go-between in deals considered shameful.

He ended up the type likely to compromise you thoroughly

if you were seen around with him often.

But this isn’t the whole story—that would not be fair.

The memory of his beauty deserves better.

There is another angle; seen from that

he appears attractive, appears

a simple, genuine child of love,

without hesitation putting,

above his honor and reputation,

the pure sensuality of his pure flesh.

Above his reputation? But society,

prudish and stupid, had it wrong.

.

Μέρες του 1896

.

Εξευτελίσθη πλήρως. Μια ερωτική ροπή του

λίαν απαγορευμένη και περιφρονημένη

(έμφυτη μολοντούτο) υπήρξεν η αιτία:

ήταν η κοινωνία σεμνότυφη πολύ.

Έχασε βαθμηδόν το λιγοστό του χρήμα·

κατόπι τη σειρά, και την υπόληψί του.

Πλησίαζε τα τριάντα χωρίς ποτέ έναν χρόνο

να βγάλει σε δουλειά, τουλάχιστον γνωστή.

Ενίοτε τα έξοδά του τα κέρδιζεν από

μεσολαβήσεις που θεωρούνται ντροπιασμένες.

Κατήντησ’ ένας τύπος που αν σ’ έβλεπαν μαζύ του

συχνά, ήταν πιθανόν μεγάλως να εκτεθείς.

Aλλ’ όχι μόνον τούτα. Δεν θάτανε σωστό.

Aξίζει παραπάνω της εμορφιάς του η μνήμη.

Μια άποψις άλλη υπάρχει που αν ιδωθεί από αυτήν

φαντάζει, συμπαθής· φαντάζει, απλό και γνήσιο

του έρωτος παιδί, που άνω απ’ την τιμή,

και την υπόληψί του έθεσε ανεξετάστως

της καθαρής σαρκός του την καθαρή ηδονή.

Aπ’ την υπόληψί του; Μα η κοινωνία που ήταν

σεμνότυφη πολύ συσχέτιζε κουτά.

. . .

Comes to rest

.

It must have been one o’clock at night

or half past one.

A corner in the wine-shop

behind the wooden partition:

except for the two of us the place completely empty.

An oil lamp barely gave it light.

The waiter, on duty all day, was sleeping by the door.

No one could see us. But anyway,

we were already so aroused

we’d become incapable of caution.

Our clothes half opened—we weren’t wearing much:

a divine July was ablaze.

Delight of flesh between

those half-opened clothes;

quick baring of flesh—the vision of it

that has crossed twenty-six years

and comes to rest now in this poetry.

.

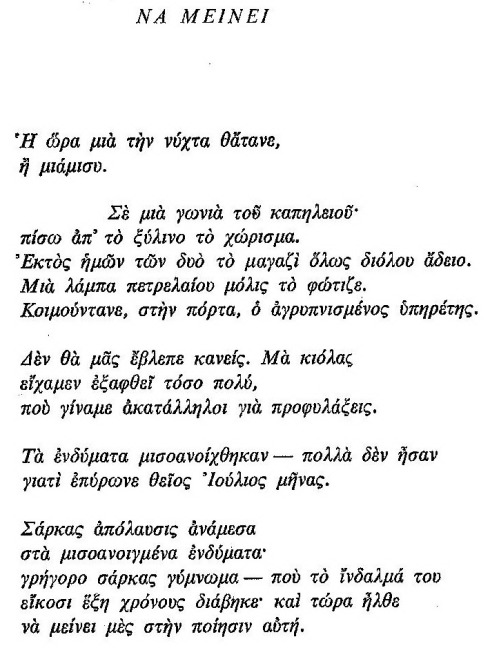

Να μείνει

.

Η ώρα μια την νύχτα θάτανε,

ή μιάμισυ.

Σε μια γωνιά του καπηλειού·

πίσω απ’ το ξύλινο το χώρισμα.

Εκτός ημών των δυο το μαγαζί όλως διόλου άδειο.

Μια λάμπα πετρελαίου μόλις το φώτιζε.

Κοιμούντανε, στην πόρτα, ο αγρυπνισμένος υπηρέτης.

Δεν θα μας έβλεπε κανείς. Μα κιόλας

είχαμεν εξαφθεί τόσο πολύ,

που γίναμε ακατάλληλοι για προφυλάξεις.

Τα ενδύματα μισοανοίχθηκαν — πολλά δεν ήσαν

γιατί επύρωνε θείος Ιούλιος μήνας.

Σάρκας απόλαυσις ανάμεσα

στα μισοανοιγμένα ενδύματα·

γρήγορο σάρκας γύμνωμα — που το ίνδαλμά του

είκοσι έξι χρόνους διάβηκε· και τώρα ήλθε

να μείνει μες στην ποίησιν αυτή.

. . .

One night

.

The room was cheap and sordid,

hidden above the suspect taverna.

From the window you could see the alley,

dirty and narrow. From below

came the voices of workmen

playing cards, enjoying themselves.

And there on that common, humble bed

I had love’s body, had those intoxicating lips,

red and sensual,

red lips of such intoxication

that now as I write, after so many years,

in my lonely house, I’m drunk with passion again.

.

Μια Νύχτα

.

Η κάμαρα ήταν πτωχική και πρόστυχη,

κρυμένη επάνω από την ύποπτη ταβέρνα.

Aπ’ το παράθυρο φαίνονταν το σοκάκι,

το ακάθαρτο και το στενό. Aπό κάτω

ήρχονταν η φωνές κάτι εργατών

που έπαιζαν χαρτιά και που γλεντούσαν.

Κ’ εκεί στο λαϊκό, το ταπεινό κρεββάτι

είχα το σώμα του έρωτος, είχα τα χείλη

τα ηδονικά και ρόδινα της μέθης —

τα ρόδινα μιας τέτοιας μέθης, που και τώρα

που γράφω, έπειτ’ από τόσα χρόνια!,

μες στο μονήρες σπίτι μου, μεθώ ξανά.

. . .

When they come alive

.

Try to keep them, poet,

those erotic visions of yours,

however few of them there are that can be stilled.

Put them, half-hidden, in your lines.

Try to hold them, poet,

when they come alive in your mind

at night or in the brightness of noon.

.

Όταν Διεγείρονται

.

Προσπάθησε να τα φυλάξεις, ποιητή,

όσο κι αν είναι λίγα αυτά που σταματιούνται.

Του ερωτισμού σου τα οράματα.

Βάλ’ τα, μισοκρυμένα, μες στες φράσεις σου.

Προσπάθησε να τα κρατήσεις, ποιητή,

όταν διεγείρονται μες στο μυαλό σου,

την νύχτα ή μες στην λάμψι του μεσημεριού.

. . . . .

All of the above poems:

from: C.P. Cavafy, Collected Poems. Translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard. Edited by George Savidis. Revised Edition. Princeton University Press, 1992

. . . . .

Konstantin Kavafis / Κωνσταντίνος Καβάφης: “I went into the brilliant night and drank strong wine, the way the Champions of Pleasure drink.”

Posted: July 1, 2012 Filed under: English, Greek, Konstantin Kavafis | Tags: Gay poets Comments Off on Konstantin Kavafis / Κωνσταντίνος Καβάφης: “I went into the brilliant night and drank strong wine, the way the Champions of Pleasure drink.”

Konstantin Kavafis (Constantine Cavafy)

(1863-1933)

Walls

With no consideration, no pity, no shame,

they’ve built walls around me, thick and high.

And now I sit here feeling hopeless.

I can’t think of anything else: this fate gnaws my mind

– because I had so much to do outside.

When they were building the walls, how could I not have noticed!

But I never heard the builders, not a sound.

Imperceptibly they’ve closed me off from the outside world.

(1896)

The Windows

In these dark rooms where I live out empty days,

I wander round and round

trying to find the windows.

It will be a great relief when a window opens.

But the windows aren’t there to be found

– or at least I can’t find them. And perhaps

it’s better if I don’t find them.

Perhaps the light will prove another tyranny.

Who knows what new things it will expose?

(1897)

I went

I didn’t restrain myself. I gave in completely and went,

went to those pleasures that were half real,

half wrought by my own mind,

went into the brilliant night

and drank strong wine,

the way the champions of pleasure drink.

(1905)

Comes to rest

It must have been one o’clock at night

or half past one.

A corner in a tavern,

behind the wooden partition:

except for the two of us the place completely empty.

A lamp barely lit gave it light.

The waiter was sleeping by the door.

*

No one could see us.

But anyway, we were already so worked up

we’d become incapable of caution.

*

Our clothes half opened – we weren’t wearing much:

it was a beautiful hot July.

*

Delight of flesh between

half-opened clothes;

quick baring of flesh – a vision

that has crossed twenty-six years

and now comes to rest in this poetry.

(1918)

The afternoon sun

This room, how well I know it.

Now they’re renting it, and the one next to it,

as offices. The whole house has become

an office building for agents, businessmen, companies.

*

This room, how familiar it is.

*

The couch was here, near the door,

a Turkish carpet in front of it.

Close by, the shelf with two yellow vases.

On the right – no, opposite – a wardrobe with a mirror.

In the middle the table where he wrote,

and three big wicker chairs.

Beside the window the bed

where we made love so many times.

*

They must be still around somewhere, those old things.

*

Beside the window the bed;

the afternoon sun used to touch half of it.

*

…One afternoon at four o’clock we separated

for a week only…And then

– that week became forever.

(1918)

Before Time altered them

They were full of sadness at their parting.

They hadn’t wanted it: circumstances made it necessary.

The need to earn a living forced one of them

to go far away – New York or Canada.

The love they felt wasn’t, of course, what it had once been;

the attraction between them had gradually diminished,

the attraction had diminished a great deal.

But to be separated, that wasn’t what they wanted.

It was circumstances. Or maybe Fate

appeared as an artist and decided to part them now,

before their feeling died out completely, before Time altered them:

the one seeming to remain for the other always what he was,

the good-looking young man of twenty-four.

(1924)

Translations from Greek into English © 1975 Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard

_____

Constantine Cavafy (Konstantin Kavafis), 1863-1933,

lived and died in the port city of Alexandria, Egypt.

His father had worked in Manchester, England, founding

an import-export firm for Egyptian cotton to the

textile industry. Between the ages of 9 and 16 Constantine

was educated in England – Victorian-era England – and

these years became important in the shaping of his poetic

sensibility (which would only emerge around the age of 40.)

Though he was fluent in English, when he began to write poetry

in earnest it was to be in his native Greek.

Cavafy never published any poems in his lifetime, rather he

had them printed privately then distributed them

– pamphlet-style – to friends and acquaintances.

His social circle was small and by all accounts he was not ashamed

of his homosexuality – but he did feel much guilt over

“auto-eroticism” – what we now call masturbation.

*

Cavafy’s early poems “Walls” and “The Windows” might

be read as the mental anxieties of a “closeted” homosexual –

yet there was no such thing in the 19th century as someone

who was “Out” anyway.

The poem “I went”, from 1905, seems to be a break-through of sorts,

Cavafy indicating – at least in the Truth that was his much-cherished

Art – Poetry – that he’s ready to write openly of his love for men.

The poems he wrote when he was in his 50s, such as “Comes to rest”,

“The afternoon sun” and “Before Time altered them”, show a mature

poet describing the universal beauty and sadness of Love – and he

does it describing sex, passion and loss between two men.

Δυνάμωσις + Κρυμμένα

Posted: July 16, 2011 Filed under: English, Greek, Konstantin Kavafis, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Δυνάμωσις + Κρυμμένα

“Growing in Spirit”

He who hopes to grow in spirit

will have to transcend obedience and respect.

He will hold to some laws

but he will mostly violate

both law and custom, and go beyond

the established, inadequate norm.

Sensual pleasures will have much to teach him.

He will not be afraid of the destructive act:

half the house will have to come down.

This way he will grow virtuously into wisdom.

*

Greek:

Δυνάμωσις

Όποιος το πνεύμα του ποθεί να δυναμώσει

να βγει απ’ το σέβας κι από την υποταγή.

Aπό τους νόμους μερικούς θα τους φυλάξει,

αλλά το περισσότερο θα παραβαίνει

και νόμους κ’ έθιμα κι απ’ την παραδεγμένη

και την ανεπαρκούσα ευθύτητα θα βγει.

Aπό τες ηδονές πολλά θα διδαχθεί.

Την καταστρεπτική δεν θα φοβάται πράξι·

το σπίτι το μισό πρέπει να γκρεμισθεί.

Έτσι θ’ αναπτυχθεί ενάρετα στην γνώσι.

*

Español:

“Creciendo en Espíritu”

El que espera crecer en espíritu

tendrá que transcender la obediencia y el respeto.

Cumplirá ciertas leyes

pero más que todo violará

la ley y la costumbre ambas, e irá más allá

de la norma establecida insuficiente.

Los placeres sensuales tendrán mucho que enseñarle.

No tendrá miedo del acto destructor:

tendrá que echar abajo la mitad de la casa.

De esta manera madurará virtuosamente en sabiduría.

*

“Hidden Things”

From all I did and all I said

let no one try to find out who I was.

An obstacle was there that changed the pattern

of my actions and the manner of my life.

An obstacle was often there

to stop me when I’d begin to speak.

From my most unnoticed actions,

my most veiled writing—

from these alone will I be understood.

But maybe it isn’t worth so much concern,

so much effort to discover who I really am.

Later, in a more perfect society,

someone else made just like me

is certain to appear and act freely.

*

Greek:

Κρυμμένα

Aπ’ όσα έκαμα κι απ’ όσα είπα

να μη ζητήσουνε να βρουν ποιος ήμουν.

Εμπόδιο στέκονταν και μεταμόρφωνε

τες πράξεις και τον τρόπο της ζωής μου.

Εμπόδιο στέκονταν και σταματούσε με

πολλές φορές που πήγαινα να πω.

Οι πιο απαρατήρητές μου πράξεις

και τα γραψίματά μου τα πιο σκεπασμένα —

από εκεί μονάχα θα με νιώσουν.

Aλλά ίσως δεν αξίζει να καταβληθεί

τόση φροντίς και τόσος κόπος να με μάθουν.

Κατόπι — στην τελειοτέρα κοινωνία —

κανένας άλλος καμωμένος σαν εμένα

βέβαια θα φανεί κ’ ελεύθερα θα κάμει.

Translated from Greek into English by Edmund Keeley / Philip Sherrard

*

Español:

“Cosas Ocultas”

De todo lo que hice y dije,

que nadie intente descubrir quien yo era.

Había un obstáculo allá que cambió el diseño

de mis actos y la manera de mi vida.

Allá había un obstáculo, a menudo,

para pararme cuando yo comenzaba a hablar.

De los actos más desapercibidos,

de la obra escrita más velada –

de aquellos solamente yo seré comprendido.

Pero quizás no vale la pena tanta inquietud,

tanto esfuerzo para descubrir quien soy yo en verdad.

Después, en una sociedad más perfecta,

algún otro – hecho justamente como yo –

con seguridad aparecerá y se comportará con libertad.

Traducciones al español por Alexander Best

_____

Constantine Cavafy (Konstantin Kavafis), 1863-1933,

was born and died in Alexandria, Egypt,

though his parents were from Greece. He

wrote most of his poems after the age of 40,

all the while holding a dull job as a civil servant.

He is one of the great poets in modern Greek, and

though the Greek originals are in rhyme, still

Keeley and Sherrard (the standard setters for 20th-century

Greek poetry translation, along with George Savidis), in their free-verse

English renderings remain true to Kavafis’ signature “pondering-aloud” style

as well as preserving the poet’s subtlety of feeling and tone.