Zócalo Poets…Volveremos en junio de 2013 / ZP will return June 2013

Posted: April 29, 2013 Filed under: IMAGES Comments Off on Zócalo Poets…Volveremos en junio de 2013 / ZP will return June 2013Zócalo Poets – ¡qué reunamos aquí en la gran plaza de poemas!

Zócalo Poets – meet us in the Square!

¡Mándanos tus poemas – en cualquier idioma!

Send us your poems – in any language!

zocalopoets@hotmail.com

Mosha Folger: “Leaving my Cold Self behind”

Posted: April 29, 2013 Filed under: English, Mosha Folger Comments Off on Mosha Folger: “Leaving my Cold Self behind”Mosha Folger

“Ancient Patience”

.

If you look back to the North

A couple of thousand years ago

To where the Atlantic ice fields

Battle the granite shield of the Arctic coast

You’d find a man staking claim to a land

That just doesn’t seem inhabitable

an Eskimo

a patient hunter who stood unmoving for hours

crouched over small bumps in the ice

subtle seal-breathing holes

Wicked winds pushing the temperature back down

from the comfort of twenty below

Facing the low sun so his shadow fell back

away from his goal

Waiting for a freezing breathe-out

to break the crystal white flatness of snow

.

Arm cocked, harpoon ready

eyes unblinking, blazing their own little holes

in the ice floe

Mouth closed, breath low

Because less movement, less sound

meant the night’s dinner was more likely to show

Yet sometimes that hunter

stood till the moon rose

before he finally shifted, breathed hard

and set off for home with nothing but cold toes

Nothing to bloody his wife’s arms to the elbows

Nothing to warm the guts of five kids

or silence the dogs’ moans

.

Nothing but the knowledge that

the next day when he woke

to stand again over that hole

maybe, just maybe

a seal would finally show him his nose

so the harpoon could come down

to deliver its lethal blow

Or maybe, just maybe

no

.

It’s that patience that allowed my people

to settle down and call the Arctic

our home.

. . .

“Summer Play”

.

In the Arctic desert where

the earth is sand and rocks

and the lichen cling

to the frayed edges of life

in granite fields

and the wet season feels like

three days of monsoon rains

.

In that place

patches of pavement

to a kid are

hallowed grounds

where devout children

offer their time

as sacrifice

with an endless circling of bikes

and an incessant bouncing of balls

like the pounding

and kneading

of rubber into cement

could stretch out

that holy land

.

How wondrous that

a tiny square of earth

can be home to so many

boundless dreams

.

But the reality is mostly

the sand and rocks

and gravel roads, and so

the games played adapt

games of writing

or drawing in the sand

and for one reason or another

chasing each other around

.

A television drawn in the dirt

with movies and shows

initialed inside

to be guessed at

D dot P dot S dot and

if someone gets it right

a frantic chase ensues

Or I Declare War

with a giant circle divided

into America and the USSR

Canada and sometimes Uganda

where the war of course

is chasing

and the fastest world leader

had dominion over all Man

.

And on the longest nights of daylight

baseball

Inuktitut style where groggy kids

up two days under constant sun

and stumbling

play with a rubber ball

by rules that themselves

are drowsy from the endless light

so the outfield

spans the whole town

making foul balls

as fair as any other

and the bases are run wrongwise

and whacking a runner

with the ball

is an out

.

Which means of course

the rest of the game is secondary

to learning how to throw

to anticipate

to picking off the right kid

in the right spot

every time

.

And so when a parent

with a voice that too

spans the whole town

finally calls in

one too many Expos

the real winners

aren’t on the team

with the most runs

but the team that

on the quick walk home

brags about the best

outs.

. . .

“Where have all the Shaman gone?”

.

In the blink of an eye

we’ve gone from a culture where

shaman conjured spirits and

swam, fed and bred

with giant Bowhead whales

for months at a time

And people held out hope that

sometime in their life

they’d be lucky enough to witness

that rare instance

of a distant-Inuit visit

Where men from another planet descended

to collect caches of rich seal fat

overloading their space-sleds

before packing up to head back

But blink

and we wake to a world where

all of that’s been reclassified filed and stacked

under the wild imaginations of

savage heathens

still unclean

cause they hadn’t discovered their

one true saviour and

path to heaven yet

Now elected Nunavut officials can be found

in a big hall amongst a big crowd

falling face down

wailing at the top of their lungs

praising Jesus’s name

and speaking in tongues

The holy spirit come upon their earthly vessel

leaving them convulsing

Spastic believers

shaking under the giant blue and white

Israeli flag they’ve hung

.

Inuit in the day

must have been some of the easiest

lost souls to convert

A hard frozen life of

struggle pain and loss made more palatable

with the promise of a kind of

spiritual dessert

Swallow the death cold and starvation down here

and when you die

enjoy the warm salvation up there

And some of those Arctic locals

fell hard for those lies

Or promises I guess you would call them

if you fell on the other side of the line

But it couldn’t have been made easy

or simplistic could it? No,

First the Anglicans and Catholics

split villages and

pit kin against kin

Families feuding over which clan

would really get to go

And which side

picked the wrong guy’s

rules to abide by

They’ve gotten over it now though

living in a kind harmony

that the rest of what we call

civilized society

should get to know

.

But now in the Arctic we have these

evangelical proselytizing types

whose fervour makes the Anglican and Catholic devotion

seem downright secular cause

they’ve got no HYPE

No souls being sucked

from bodies to on high

No chanting and dancing

with arms to the sky

No religious stakes in the continuation

of the state of Palestine

No possession

The craziest thing they’ve got

is a little blood into wine

Maybe a little shaman incantation

would do those folks some good

Could we at least get them a little reading

from the Koran or Talmud?

That’s unlikely though

Their faith blinds them so deep

The Good News Bible’s the only text

their eyes can see

We’ll have to get a closet shaman

to do a little midnight chanting

see if we can’t set some of those zealots free.

. . .

“Leaving my Cold Self behind”

.

Now there will be no more falling down

unique crunching packing sound

or children who know no other way to live winter

than to tumble sideways and upside-down

from snow banks ten feet off the ground

There will be no snow wind-blown

from parts unknown to all

but the most trained hunters

who brave the vast white fields alone

There will be no high-pitched wailing moan

of snowmobiles flying down

snow-packed gravel roads

No riders with grins plastered

Reveling in their temporary freedom from

small-town poor-me isolation syndrome

There will be no husky howls to wake me

to call me to their battle with the wind

the wind that howls back in kind

and relentless remorseless never fails to win

There will be no more dancing northern lights

chased from their nightly show

by southern skyline stage-fright

There will be only the warm glow

of a cold city that states its case

with what it sees as some divine right

to throw its gaudy remnants

high and loud into the night

There will be only nights where time is slowed

No sleep no comfort no peace

only this page this pen my words

and my message that

no matter the price sometimes

you just have to come in out of the cold.

. . .

“Old Indifferences”

.

Inuit existence was dependent partly on every member

of the encampment being able to at the very least get up

on their own two feet walk across the jagged tundra to follow

the moving caribou so everyone could eat

.

So we adopted an effective means of excising inefficient limbs

from the family tree that left the aged floating on ice pans and

insolent sons turned away to find their own path through

the cruel Arctic days

.

This isn’t a tradition we should reprise as it slides snugly into

its place in the still mostly unwritten Inuit histories but

it has a related convention that’s made its way down into

unofficial modern Inuit custom

.

If you’ve walked downtown Montreal you’ve seen it and in Ottawa

the spring thaw brings about the re-emergence in earnest of the

panhandling Eskimos downtown between the Mall and King Edward

on Rideau Street

.

Whether these people are a nuisance isn’t a question to me because

I have to ask if these people are friends or family maybe a second cousin

and do I have to follow protocol stop and ask a few

inconsequential questions

.

I try to avoid having to do that by changing up my Inuk stride

and remembering that from a distance I could look Thai

but Inuit could never fully ostracize so when I meet one

I stop say hi and try to be polite

.

I ask about my friend their son despite the likelihood that I

was the last to see their child and it hurts inside when they

ask and I have to tell them I hadn’t seen their kid in a little while but that

I knew he wasn’t going to trial

.

It requires a certain distance to sit back and witness these lives with blood

that courses from the same point as mine float away on slabs of concrete ice

but disease strikes and existence has always insisted

on a little bit of indifference.

.

All poems © Mosha Folger

. . .

Mosha Folger (aka M.O.) was born in Frobisher Bay, North-West Territories (now called Iqaluit, Nunavut) to an Inuk mother and American father. A poet, writer, performer, and “Eskimocentric” spoken-word/hiphop rhymer, Mosha has taken part in the Weesageechak Begins to Dance festival, also at WestFest in Ottawa, the Railway Club in Vancouver, and the Great Northern Arts Festival in Inuvik (where he was chosen a Best New Artist). His video, Never Saw It (2008), combined breakdancing with traditional Inupiat dancing, and was an official selection at the Winnipeg Aboriginal Film Festival. His very-personal film, Anaana, examined the effects of residential school (upon his mother). His hiphop song Muscox (2009), with Kinnie Starr, includes lyrics that refer to the suicide of a young friend: “I couldn’t be there when they buried my boy Taitusi … epitome of a boy who should grow into an Inuk man … artistic and witty … too smart for his own good God DAMN, too smart to live shitty … … Not knowing when he died / part of the rest of us went with him.” In North America circa 1491 (2011) – from his album String Games (with Geothermal M.C.) – he says he’ll “show you how far back in time you can date my rhyme … I’m a native son but I speak a foreign tongue – this is North America circa 1491.” And: “I’m out to win this – but the prize isn’t for the witless.”

Hiphop as self-expression for Inuit youth of the next generation younger than Folger is bursting into being, and performers such as Hannah Tooktoo of Nunavik (Northern Québec) effortlessly combine it with the unique “throat singing” of older generations of Inuk.

Mosha has been an active poetry performer in Ottawa, also a member of the Bill Brown 1-2-3 Slam collective. At Tungasuvvingat Inuit and at the Ottawa Inuit Children’s Centre he has brought the power and the fun of spoken-word and hiphop to teens and children.

. . . . .

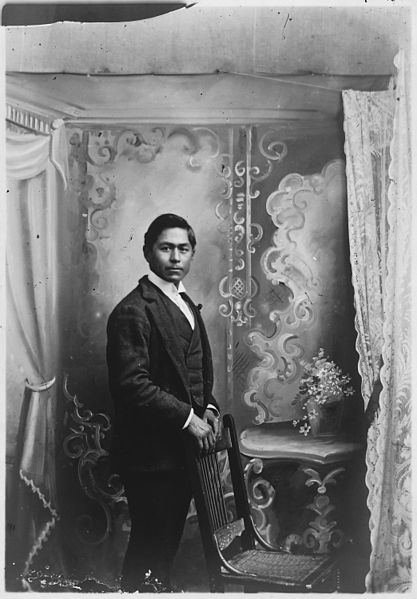

At a studied glance: Native-American / First Nations, Métis and Inuit photographers

Posted: April 28, 2013 Filed under: IMAGES Comments Off on At a studied glance: Native-American / First Nations, Métis and Inuit photographersTsimshian photographer Benjamin Haldane_portrait of David Kininnook of Saxman, Alaska_1907

Benjamin Haldane_Little boy with toy pistol

Richard Throssel (Creek/Crow)_Smoking Cigarette_1910

Richard Throssel_Two little girls

Horace Poolaw (Kiowa)_Little boy_1929

Horace Poolaw_Trecil Poolaw Unap_1929

Martín Chambi, Quechua/Peruvian portrait photographer_Self-portrait_1922

Martín Chambi_Ezequiel Arce’s Family with their harvest of potatoes_Cuzco, Perú_ 1934

Luis González Palma_Mestizo photographer from Guatemala_La Lotería II_1989

Luis González Palma_El Angel_1990

Shelley Niro (Bay of Quinte Mohawk)_The Rebel_1987

Shelley Niro_Mohawks in beehives_1991

Nish Photoluver_The Rez 2000

Nish Photoluver_Clothesline, Northern Ontario_2000

Nish Photoluver_Wow

Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie (Seminole-Muscogee-Navajo)_Grandma_2003

Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie_Chi-bon_2003

Jordan Bennett (Mi’kmaw skateboarder/photographer)_Traditional Mi’kmaq Surfboard_2007

Beckie Etukeok (Inupiaq/Tlingit)_Bipsurruk (Red Salmon)_2009

Peggy Fontenot_Robert Banks, Cherokee Freedman, 2008_from Fontenot’s Merging Cultures series about Black Indians

Kimowan Metchewais (Cree, Cold Lake First Nation)_Cold Lake

Kimowan Metchewais_War Pony_2010

Larry McNeil (Tlingit)_photo-collage from I’m Angry You Are Bad: Raven, carbon emissions, and the global climate crisis_2011

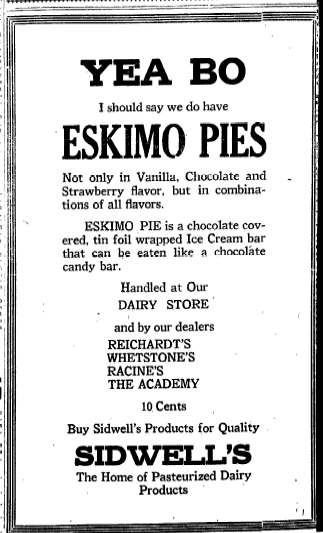

“Yeah Bro, I should say we do have Eskimo Lies”: the poetry of Inuit writer Norma Dunning

Posted: April 25, 2013 Filed under: English, Inuktitut, Norma Dunning Comments Off on “Yeah Bro, I should say we do have Eskimo Lies”: the poetry of Inuit writer Norma Dunning.

Eskimo Pie I

.

Found on Wikipedia under “Eskimo Pie”:

.

My response to the ad:

.

YEAH BRO

I should say we do have

ESKIMO LIES

Not only in N. Canada and

Urban centers, but in

combina-

tions of all flavors.

Eskimo Lies is a

sugercoated

conception of Northern

Peoples

Handled at Our

GOVERNMENT OFFICES

and by our general public

LIBERALS, PCs, RCMP

& THE

ACADEMY

NO SENSE

Buy Eskimo Lies – A Quality

Product of Canada

The Home of PASTEURIZED

Inuit History

.

Eskimo Pie II

Oh give me a piece of that Eskimo Pie.

.

16 crushed chocolate wafers

4 tbsp of melted butter

.

An entire grouping of humanity

Secured in residential school, left to die

Let me see that chubby little brown face

Filled with 32 marshmallows

.

1/2 cup milk

1/8 tsp m.s.g.

Smiling inside a padlocked fur-ringed space

Include 1 tbsp of vanilla and

1 cup of heavy cream – whipped,

Beat the little heathens

Put them in their place

Melt the marshmallows,

Along with their mother tongues

Whiten with milk,

.

Add the salt

To the wounds

.

And vanilla in a double-boiler

Turn the heat on high

Bring to a boil

Simmer and strain

Removing all their relatives

Cool the filling

Fold in the whipped cream

Pour into a pie plate

.

Slice and Assimilate

.

To the Eskimos of Canada

.

We came here to make them better

Teaching them church and knitting sweaters

.

Changed their names and made them right

These dirty little animals full of fight

.

Taught them how to wash their hands

Took them off their hostile lands

.

Bringing them to our enlightened age

Gave them names on a page

.

They’re happier than they’ve ever been

A better side of life they have finally seen

.

Our mission is soon complete

They will no longer eat raw meat

.

We’ll soldier on in our god’s name

These lowly people we will tame

.

They will thank us for this soon one day

And on their land we will forever stay

.

The Necklace

(Or Forms of 20th Century Shackling – The Eskimo Identification Canada System 1941-1978)

I gave you a necklace made out of sting

Such a pretty thing, such a pretty thing

I told you to wear forever and always

Such a pretty thing, such a pretty thing

I had a number put on it

Just for me!

I told you to remember it always

I did oh I did and oh I still do!

I said it was better than your name

It is oh it is and oh it still is!

If you didn’t have it I won’t be yours

Oh please, no threats, I’m yours always

Without it there would be no happy ever after

Oh please, no threats, no threats

PLEASE!

I told you to write it on all pieces of paper

I will and I have and I must and I do!

If it gets lost – we’re over!

I won’t and I haven’t and I must say I do!

This necklace is the best thing that’s ever

Happened to you

I seem to be lacking air or is

it hair or do I

dare say,

“I’m turning blue”?

.

Kudlik/Qulliq

by

(Norma – in Inuktitut)

.

There is more to this lamp than the lighting

of it. Shared in its shadows are laughter,

crying and the tears of so long ago.

The tears of a sickness changing us for

ever. Echoes of tuberculosis.

Once we were well and we gathered manniq. (wick of moss)

We slept in peace under spring stars hearing

Our giggles and sighs mixed only with the

sounds of the earth. Disease took us from

home and away, far away to stay locked

in the prison of white walls. To cough up

blood of my puvak and long for home. (lung)

No more the qulliq to warm our spirits (stone lamp)

Warm our hearts, heat our lives, feed our stomachs.

Our revolution came in Quallnaat

Bacteria and the light of the

qulliq grew dim. Black wisps answered our cries

blowing out the wick of what we once were.

.

For Mini Aodla-Freeman, the last living Inuit woman in Canada who knows the traditional uses of the Qulliq. She is the last keeper of this traditional Inuit flame.

. . . . .

In the poet’s words:

My name is Norma Dunning. I am a Beneficiary of Nunavut and a first-year M.A. Student at the University of Alberta with the inaugural class of M.A. Students in the Faculty of Native Studies. I am an urban Inuit writer. My M.A. Thesis is based on the Eskimo Identification Canada System which ran in Canada from 1941 to 1978. It is a system, simply put, that replaced Inuit names with numbers. The University of Alberta has been very kind towards my writing and I have been awarded the James Patrick Follinsbee Prize for Creative Prose (2011) and the Stephen Kapalka Memorial Prize for Prose (2012). My creative work, both prose and poetry, has never been published in hard copy. This does not stop me from writing and I would encourage all writers to remember that we write because of what is inside of us needing to get out onto a page.

Matna – Norma

Earth Day poems: “I’ve wanted to speak to the world for sometime now about you.”

Posted: April 22, 2013 Filed under: English, Maurice Kenny | Tags: Poems for Earth Day Comments Off on Earth Day poems: “I’ve wanted to speak to the world for sometime now about you.”Maurice Kenny (Mohawk poet and teacher, born 1929)

new song

.

We are turning

eagles wheeling sky

We are rounding

sun moving in the air

We are listening

to old stories

Our spirits to the breeze

the voices are speaking

Our hearts touch earth

and feel dance in our feet

Our minds in clear thought

we speak the old words

We will remember everything

knowing who we are

We will touch our children

and they will dance and sing

As eagle turns, sun rises, winds blow,

ancestors, be our guides

Into new bloodless tomorrows.

. . .

ceremony

.

urgent/

night/ and not

even rain could

stop love-

making

in shadows

.

street unbuckled

rain slid down neck/

nipple/crotch

exposed to hands

all elements/

ancient mouth

tender as thistle-down

swallowed centuries

.

spent urgency

.

life re-newed/continues

stories are told

under winter moons

big orange melons

purple plums

.

Seminoles dance in this light

celebrate

Comanches dance in this light

celebrate, too/together

fixed in sweat/suction

of flesh to flesh

celebrate, too

.

rain/ and rain

washes sky clean

everything

is green

green sun, green moon, green dreams

and there is only

the good feeling

.

now to sleep

. . .

curt suggests

.

Passing through,

wolf presses snow,

disappears

as though winter moon

washed the fallen snow

drifting the mountain slope.

.

He howls

and I’m assured things

of the old mountain will

not only stay but survive.

It is all about survival…

not the internet, online

or standing, waiting for a big mac.

Humans have survived,

some say, perhaps too long.

Beauty. Nobility. Poetry.

Rewards for the warrior

who brought the village fire.

.

Wolf is always hunting.

Winter is long and frozen,

dark and deadly dangerous.

Farmers are armed.

Sleep without fat is eternal

and pups are bones in enemy’s teeth.

.

The politic is not the language,

not even the song belongs to the voice

until fires are built, walls erected

and it is safe to sleep. Then sing.

.

Raccoon falls from the elm,

a high branch.

Wolf watches from the hill.

Vocables quaver.

Rocks learn to sing

in the water of the swift river.

Now we stand erect

and walk through the green woods.

Our songs are safely sculpted

into ice and pray

it won’t melt

to the touch of the ear bending to echoes.

.

I don’t care if you are only passing

through these woods. Stay.

. . .

hawkweed

.

I’ve wanted to speak to the world

for sometime now about you.

There are many who confuse you with another wild

flower which is, in truth,

no relation not even

a distant, kissing cousin.

You don’t even look alike

nor survive in the same country-side.

Many people claim you are Indian

Paint Brush. Just today

a friend spotted your bloom

decorating the roadside grasses

and called out… “O there’s a beauty…

a paint brush.” I had

to explain the brush blooms

out west…Oklahoma…and

is red. Period.

.

You, on the other hand,

blossom here in the east

and your bloom is fire-

red or orange and sometimes

yellow and you came on the

Mayflower with the others

from across the seas.

.

Farmers think the hawk eats

your blossoms for sight,

vision, but we’re happy

you show up every spring

on the roadside or in the field

bringing colour to morning

though dotted with dew

or snake-spittle, bee-balm.

Up here in the Adirondacks

I’ve seen you rise in snow

when April/May arrived late.

.

Well, all I’ve really got

to say is if the farmer is right

then the red-tail is pretty smart

and deserves your sight.

Now we have to get the the other

humans to admit just who you are.

. . . . .

All poems © Maurice Kenny, from his collection In the Time of the Present (2000)

Photograph: Hieracium caespitosum a.k.a. meadow or field hawkweed

Poems for Earth Day: “The earth of my blood”: O’Connor, Ben the Dancer, La Fortune

Posted: April 22, 2013 Filed under: Ben the Dancer, English, Lawrence William O'Connor, Richard La Fortune / Anguksuar | Tags: Native-American poets, Poems for Earth Day Comments Off on Poems for Earth Day: “The earth of my blood”: O’Connor, Ben the Dancer, La FortuneLawrence William O’Connor (Winnebago poet)

“O Mother Earth”

.

Never will I plough the earth.

I would be ripping open the breast of my mother.

.

Never will I foul the rivers.

I would be poisoning the veins of my mother.

.

Never will I cut down the trees.

I would be breaking off the arms of my mother.

.

Never will I pollute the air.

I would be contaminating the breath of my mother.

.

Never will I strip-mine the land.

I would be tearing off her clothes, leaving her naked.

.

Never will I kill the wild animals for no reason.

I would be murdering her children, my own brothers and sisters.

.

Never will I disrespect the earth in anyway.

Always will I walk in beauty upon the earth my mother,

Under the sky my father,

In the warmth of the sun my sister,

Through the glow of the moon my brother.

. . .

Ben the Dancer (Yankton Lakota-Sioux, Rosebud (Sicangu), South Dakota)

“My Rug Maker Fine”

.

slowly as I laid my head

upon his chest

the rain outside beckoned

for me to kiss him

we forgot the names that were called

and as I looked into his deep brown eyes

I saw the earth of his people

the earth of his blood

and the earth of his birth

looking at me

.

there was much to be said

on that rainy night

but talking came secondary

and not much was said

some names were meant to scald

they can break steadfast ties

then I heard the earth of his people

the earth of his blood

and the earth of his birth

telling me

.

he left on that rainy night

without a kiss

he went home forever

the rain beckoned at him to go

the earth of his people told me

he was going home

the earth of his blood called him

to come home

and the earth of his birth took him

from me

.

oh how my heart went on a dizzy flight

I will him miss

knowing this was going to sever

our hearts and leave a hole

I know the drum of his people

that called him home

I feel the pulse of his blood

that drew him there

I smell the scent of his birth

that made me let him go

.

I have endured the name

the scalding brand

I stand on my own feet now

the earth of my people

the earth of my blood

and the earth of my birth

told me to let you go

I listened

I know now

and we are free.

. . .

Richard La Fortune/Anguksuar (Yupik Eskimo, born 1960, Bethel, Kuskokvagmiut, Alaska)

.

I have picked a bouquet for you:

I picked the sky,

I picked the wind,

I picked the prairies with their waving grasses,

I picked the woods, the rivers, brooks and lakes,

I picked the deer, the wildcat, the birds and small animals.

I picked the rain – I know you love the rain,

I picked the summer stars,

I picked the sunshine and the moonlight,

I picked the mountains and the oceans with their mighty waters.

I know it’s a big bouquet, but open your arms wide;

you can hold all of it and more besides.

.

Your mind and your love will

let you hold all of this creation.

. . . . .

All poems © each poet: Lawrence William O’Connor, Ben the Dancer, Richard La Fortune

Selections are from a compilation of “Gay American Indian” (including Lesbian and Two-Spirits) poetry, short stories and essays – Living the Spirit – published in 1988.

Poems for Earth Day: Rita Joe’s “Mother Earth’s Hair”, “There is Life Everywhere” and “When I am gone”

Posted: April 22, 2013 Filed under: English, Rita Joe | Tags: Poems for Earth Day Comments Off on Poems for Earth Day: Rita Joe’s “Mother Earth’s Hair”, “There is Life Everywhere” and “When I am gone”Rita Joe (Mi’kmaw poet, 1932-2007)

“Mother Earth’s Hair”

.

In August 1989 my husband and I were in Maine

Where he died, I went home alone in pain.

We had visited each reservation we knew

Making many friends, today I still know.

Near a road a woman was sitting on the ground

She was carefully picking strands of grass

Discarding some, holding others straight

I asked why was she picking so much.

She said, “They are ten dollars a pound.”

My husband and I sat alongside of her, becoming friends.

A bundle my husband picked then, later my treasure.

I know, as all L’nu’k* know,

that sweetgrass is mother earth’s hair

So dear in my mind my husband picking shyly for me

Which he never did before, in two days he will leave me.

Today as in all days I smell sweetgrass, I think of him

Sitting there so shy, the picture remains dear.

.

*L’nu = an Aboriginal person

. . .

“There is Life Everywhere”

.

The ever-moving leaves of a poplar tree lessened my anxiety as I walked through the woods trying to make my mind work on a particular task I was worried about. The ever-moving leaves I touched with care, all the while talking to the tree. “Help me,” I said. There is no help from anywhere, the moving story I want to share. There is a belief that all trees, rocks, anything that grows, is alive, helps us in a way that no man can ever perceive, let alone even imagine. I am a Mi’kmaw woman who has lived a long time and know which is true and not true, you only try if you do not believe, I did, that is why my belief is so convincing to myself. There was a time when I was a little girl, my mother and father had both died and living at yet another foster home which was far away from a native community. The nearest neighbours were non-native and their children never went near our house, though I went to their school and got along with everybody, they still did not go near our home. It was at this time I was so lonely and wanted to play with other children my age which was twelve at the time. I began to experience unusual happiness when I lay on the ground near a brook just a few metres from our yard. At first I lay listening to the water, it seemed to be speaking to me with a comforting tone, a lullaby at times. Finally I moved my playhouse near it to be sure I never missed the comfort from it. Then I developed a friendship with a tree near the brook, the tree was just there, I touched the outside bark, the leaves I did not tear but caressed. A comforting feeling spread over me like warmth, a feeling you cannot experience unless you believe, that belief came when I was saddest. The sadness did not return after I knew that comfortable unity I shared with all living animals, birds, even the well I drew water from. I talked to every bird I saw, the trees received the most hugs. Even today I am sixty-six years old, they do not know the unconditional freedom I have experienced from the knowledge of knowing that this is possible. Try it and see. There is life everywhere, treat it as it is, it will not let you down.

. . .

“When I am gone”

.

The leaves of the tree will shiver

Because aspen was a friend one time.

Black spruce, her arms will lay low

And across the sky the eagles fly.

The mountains be still

Their wares one time like painted pyramids.

All gold, orange, red splash like we use on face.

The trees do their dances for show

Like once when she spoke

I love you all.

Her moccasin trod so softly, touching mother

The rocks had auras after her sweat

The grass so clean, she pressed it to cheek

Every blade so clean like He wants you to see.

The purification complete.

“Kisu’lkw” you are so good to me.

I leave a memory of laughing stars

Spread across the sky at night.

Try counting, no end, that’s me – no end.

Just look at the leaves of any tree, they shiver

That was my friend, now yours

Poetry is my tool, I write.

. . . . .

For more of Rita Joe’s poems please see our April 11th posts…

Alootook Ipellie: Artist, Writer, Dreamer !

Posted: April 11, 2013 Filed under: Alootook Ipellie, English, Writer-Artist-Dreamer: Alootook Ipellie Comments Off on Alootook Ipellie: Artist, Writer, Dreamer !

ZP_The agony and the ecstasy_illustration for a short story in Arctic Dreams and Nightmares_Alootook Ipellie, 1993

Alootook Ipellie (1951-2007)

“It Was Not ‘Jajai-ja-jiijaaa‘ Anymore – But ‘Amen’”

.

It was in the guise of the Holy Spirit

That they swooped down on the tundra

Single-minded and determined

To change forever the face

Of ancient Spirituals

These lawless missionaries from places unknown

Became part of the landscape

Which was once the most sacred tomb

Of lives lived long ago

The last connection to the ancient Spirits

Of the most sacred land

Would be slowly severed

Never again to be sensed

Never again to be felt

Never again to be seen

Never again to be heard

Never again to be experienced

Sadness supreme for the ancient culture

Jubilation in the hearts of the converters

Where was justice to be found?

They said it was in salvation

From eternal fire

In life after death

And unto everlasting Life in Heaven

A simple life lived

On the sacred land was no more

The psalm book now replaced

The sacred songs of shamans

The Lord’s Prayer now ruled

Over the haunting chant of revival

It was not ‘Jajai-ja-jiijaaa’ anymore

But-

‘Amen’

. . .

“How noisy they seem”

.

I saw a picture today, in the pages of a book.

It spoke of many memories of when I was still a child:

Snow covered the ground,

And the rocky hills were cold and gray with frost.

The sun was shining from the west,

And the shadows were dark against the whiteness of the

Hardened snow.

.

My body felt a chill

Looking at two Inuit boys playing with their sleigh,

For the fur of their hoods was frosted under their chins,

From their breathing.

In the distance, I could see at least three dog teams going away,

But I didn’t know where they were going,

For it was only a photo.

I thought to myself that they were probably going hunting,

To where they would surely find some seals basking on the ice.

Seeing these things made me feel good inside,

And I was happy that I could still see the hidden beauty of the land,

And know the feeling of silence.

. . .

“Walking Both Sides of an Invisible Border”

.

It is never easy

Walking with an invisible border

Separating my left and right foot

I feel like an illegitimate child

Forsaken by my parents

At least I can claim innocence

Since I did not ask to come

Into this world

Walking on both sides of this

Invisible border

Each and everyday

And for the rest of my life

Is like having been

Sentenced to a torture chamber

Without having committed a crime

Understanding the history of humanity

I am not the least surprised

This is happening to me

A non-entity

During this population explosion

In a minuscule world

I did not ask to be born an Inuk

Nor did I ask to be forced

To learn an alien culture

With its alien language

But I lucked out on fate

Which I am unable to undo

I have resorted to fancy dancing

In order to survive each day

No wonder I have earned

The dubious reputation of being

The world’s premier choreographer

Of distinctive dance steps

That allow me to avoid

Potential personal paranoia

On both sides of this invisible border

Sometimes the border becomes so wide

That I am unable to take another step

My feet being too far apart

When my crotch begins to tear

I am forced to invent

A brand new dance step

The premier choreographer

Saving the day once more

Destiny acted itself out

Deciding for me where I would come from

And what I would become

So I am left to fend for myself

Walking in two different worlds

Trying my best to make sense

Of two opposing cultures

Which are unable to integrate

Lest they swallow one another whole

Each and everyday

Is a fighting day

A war of raw nerves

And to show for my efforts

I have a fair share of wins and losses

When will all this end

This senseless battle

Between my left and right foot

When will the invisible border

Cease to be.

.

(1996)

. . . . .

Alootook Ipellie

“Self-Portrait: Inverse Ten Commandments” (1993)

.

I woke up snuggled in the warmth of a caribou-skin blanket during a vicious storm. The wind was howling like a mad dog, whistling whenever it hit a chink in my igloo. I was exhausted from a long, hard day of sledding with my dogteam on one of the roughest terrains I had yet encountered on this particular trip.

.

I tried going back to sleep, but the wind kept waking me as it got stronger and even louder. I resigned myself to just lying there in the moonless night, eyes open, looking into the dense darkness. I felt as if I was inside a black hole somewhere in the universe. It didn’t seem to make any difference whether my eyes were opened or closed.

.

The pitch darkness and the whistling wind began playing games with my equilibrium. I seemed to be going in and out of consciousness, not knowing whether I was still wide awake or had gone back to sleep. I also felt weightless, as if I had been sucked in by a whirlwind vortex.

.

My conscious mind failed me when an image of a man’s face appeared in front of me. What was I to make of his stony stare – his piercing eyes coloured like a snowy owl’s, and bloodshot, like that of a walrus?

.

He drew his clenched fists in front of me. Then, one by one, starting with the thumbs, he spread out his fingers. Each finger and thumb revealed a tiny, agonized face, with protruding eyes moving snake-like, slithering in and out of their sockets! Their tongues wagged like tails, trying to say something, but only mumbled, since they were sticking too far out of their mouths to be legible. The pitch of their collective squeal became higher and higher and I had to cover my ears to prevent my eardrums from being punctured. When the high pitched squeal became unbearable, I screamed like a tortured man.

.

I reached out frantically with both hands to muffle the squalid mouths. Just moments before I grabbed them, they faded into thin air, reappearing immediately when I drew my hands back.

.

Then there was perfect silence.

I looked at the face, studying its features more closely, trying to figure out who it was. To my astonishment, I realized the face was that of a man I knew well. The devilish face, with its eyes planted upside down, was really some form of an incarnation of myself! This realization threw me into a psychological spin.

.

What did this all mean? Did the positioning of his eyes indicate my devilish image saw everything upside down? Why the panic-stricken faces on the tips of his thumbs and fingers? Why were they in such fits of agony? Had I indeed arrived at Hell’s front door and Satan had answered my call?

.

The crimson sheen reflecting from his jet-black hair convinced me I had arrived at the birthplace of all human fears. His satanic eyes were so intense that I could not look away from them even though I tried. They pulled my mind into a hypnotic state. After some moments, communicating through telepathy, the image began telling me horrific tales of unfortunate souls experiencing apocalyptic terror in Hell’s Garden of Nede.

.

The only way I could deal with this supernatural experience was to fight to retain my sanity, as fear began overwhelming me. I knew it would be impossible for me to return to the natural, physical world if I did not fight back.

.

This experience made my memory flash back to the priestly eyes of our local minister of Christianity. He had told us how all human beings, after their physical death, were bound by the doctrine of the Christian Church that they would be sent to either Heaven or Hell. The so-called Christian minister had led me to believe that if I retained my good-humoured personality toward all mankind, I would be assured a place in God’s Heaven. But here I was, literally shrivelling in front of an image of myself as Satan incarnate!

.

I couldn’t quite believe what my mind telepathically heard next from this devilish man. As it turned out, the ten squalid heads represented the Inverse Ten Commandments in Hell’s Garden of Nede. To reinforce this, the little mouths immediately began squealing acidic shrills. They finally managed to make sense with the motion of their wagging tongues. Two words sprang out thrice from ten mouths in unison: “Thou Shalt! Thou Shalt! Thou Shalt!” I could not believe I was hearing those two words. Why was I the object of Satan’s wrath? Had I been condemned to Hell’s Hole?

.

My mind flashed back to the solemn interior of our local church once more where these words had been spoken by the minister: “God made man in His own image.” In which case, the Satan could also have made man in his own image. So I was almost sure that I was face to face with my own image as the Satan of Hell!

.

“Welcome, welcome, welcome,” the image said, his hands reaching for mine. “Welcome to the Garden of Nede.”

.

I found his greeting repulsive, more so when he wrapped his squalid fingertips around my hands. The slithering eyes retreated into their sockets, closing their eyelids. The wagging tongues began slurping and licking my hands like hungry tundra wolves. I pulled my hands away as hard as I could but wasn’t able to budge them.

.

The rapid motion of their sharp tongues cut through my skin. The cruelty inflicted on me was unbearable! Blood was splattering all over my face and body. I screamed in dire pain. As if by divine intervention, I instinctively looked down between the legs of my Satanic image. I bolted my right knee upward as hard as I could muster toward his triple bulge. My human missile hit its target, instantly freeing my hands. In the same violent moment, the image of myself as the Satan of Hell’s Garden of Nede disappeared into thin air. Only a wispy odour of burned flesh remained.

.

Pitch darkness once again descended all around. Total silence. Calm. Then, peace of mind…

.

Some days later, when I had arrived back in my camp, I was able to analyze what I had experienced that night. As it turned out, my soul had gone through time and space to visit the dark side of myself as the Satan incarnate. My soul had gone out to scout my safe passage to the cosmos. The only way any soul is freed is for it to get rid of its Satan incarnate at the doorstep of Hell’s Garden of Nede. If my soul had not done what it did, it would have remained mired in Hell’s Garden of Nede for an eternity after my physical death. This was a revelation that I did not quite know how to deal with. But it was an essential element of my successful passage to the cosmos as a soul and therefore, the secret to my happiness in afterlife!

When Inuk illustrator and writer Alootook Ipellie died of heart attack at the age of 56 in 2007 he had only just unveiled a series of new drawings at an Ottawa exhibition – this, after a decade of artistic silence. Paul Gessell of The Ottawa Citizen wrote: “Ipellie’s technical skills are unbeatable. His content ranges from playfully innocent to devilishly searing. These pen-and-ink drawings, although often minimal, carry a wallop.”

Born in 1951 to Napatchie and Joanassie at a nomadic hunting camp on Baffin Island, Ipellie’s family moved to Frobisher Bay (later Iqaluit) when Alootook was a little boy. As an adult the shy and thoughtful Ipellie lived in Ottawa for most of his life, and that was where he completed high school in the late 1960s. Although he enrolled in a lithography course at West Baffin Co-op, he dropped out of it in 1972 and took a job as both typist and translator for Inuit Today magazine. He also began to do one-box cartoons for the magazine, commenting on social issues with a wry humour that Inuit readers appreciated. He would wear many hats at Inuit Today, eventually becoming editor. In the early 1990s he drew a popular comic called “Nuna and Vut” for Nunatsiaq newspaper where he also penned a column called “Ipellie’s Shadow”.

Not one to travel – although he did plan to return to Nunavut in 2008, having grown tired of southern life – still, Ipellie had ventured as far as Germany and Australia to tour with his pen-and-ink drawings which were slowly gaining recognition – slowly very slowly, because the art collectors’ preference continues to be for the beautiful bird images of Kenojuak Ashevak (bless her!) over those of Annie Pootoogook – where the here-and-now ‘real-ness’ factor is paramount.

A poet and short-story writer as well, Ipellie explored a vividly creative imagination in his 1993 story-book with illustrations: Arctic Dreams and Nightmares.

In the preface he wrote: “This is a story of an Inuk who has been dead for a thousand years and who then recalls the events of his former life through the eyes of his living soul. It’s also a story about a powerful shaman who learned his shamanic trade as an ordinary Inuk. He was determined to overcome his personal weaknesses, first by dealing with his own mind and, then, with the forces out of his reach or control.”

In Arctic Dreams and Nightmares bawdy humour and frank descriptions of sex and violence give Ipellie’s stories much in common with the Inuit people’s stories from olden times. Ipellie writes of his main character’s encounter with his Satanic other self; of his crucifixion, too, complete with hungry wolves; of Sedna, the Inuit Mother of Sea Beasts’ sexual frustration and how shamans came up with a plan to help satisfy Her so that she would release walrus and seal once again for the starving ice fishermen and their families; a hermaphrodite shaman who is executed via harpoon plus bow-and-arrow; and a sealskin blanket-toss game for the purpose of throwing a man all the way up to ‘heaven’.

Alootook Ipellie’s perspective on his life as an Inuk was this:

“In some ways, I think I am fortunate to have been part and parcel of an era when cultural change pointed its ugly head to so many Inuit who eventually became victims of this transitional change. It is to our credit that, as a distinct culture, we have kept our eyes and intuition on both sides of the cultural tide, aspiring, as always, to win the battle as well as the war. Today, we are still mired in the battle but the war is finally ending.”

.

We thank John Thompson of the Iqaluit weekly Nunatsiaq News for biographical details of Alootook Ipellie’s life.

. . . . .

Mi’kmaw I am: Poems of Rita Joe + We are the Dreamers

Posted: April 11, 2013 Filed under: English, Mi'kmaq / Míkmawísimk, Mi'kmaw I am: Poems of Rita Joe + We are the Dreamers, Rita Joe Comments Off on Mi’kmaw I am: Poems of Rita Joe + We are the DreamersRita Joe

(Mi’kmaw poet, 1932-2007, Whycocomagh, Nova Scotia, Canada)

.

“A Mi’kmaw Cure-All for Ingrown Toenail”

.

I have a comical story for ingrown toenail

I want to share with everybody.

The person I love and admire is a friend.

This is her cure-all for an elderly problem.

She bought rubber boots one size larger

And put salted water above the toe

Then wore the boots all day.

When evening came they cut easy,

The ingrown problem much better.

I laughed when I heard the story.

It is because I have the same tender distress

So might try the Mi’kmaw cure-all.

The boots are there, just add the salted water

And laugh away the pesky sore.

I’m even thinking of bottling for later use.

. . .

“Street Names”

.

In Eskasoni there were never any street names, just name areas.

There was Qam’sipuk (Across The River),

74th Street now, you guess why the name.

Apamuek, central part of Eskasoni, the home of Apamu.

New York Corner, never knew the reason for the name.

There is Gabriel Street, the church Gabriel Centre.

Espise’k, Very Deep Water.

Beach Road, naturally the beach road.

Mickey’s Lane. There must be a Mickey there.

Spencer’s Lane, Spencer lives there, why not Arlene? His wife.

Cremo’s Lane, the last name of many people.

Crane Cove Road, the location of Crane Cove Fisheries.

Pine Lane, a beautiful spot, like everywhere else in Eskasoni.

Silverwood Lane, the place of silverwood.

George Street, bet you can’t guess who lives there.

Denny’s Lane, the last name of many Dennys.

Paul’s Lane, there are many Pauls, Poqqatla’naq.

Johnson Place, many Johnsons.

Morris Lane, guess who?

Horseshoe Drive, considering no horses in Eskasoni.

Beacon Hill, elegant place name,

I used to work at Beacon Hill Hospital in Boston.

Mountain Road,

A’nslm Road, my son-in-law Tom Sylliboy, daughter,

three grandchildren live there,

and Lisa Marie, their poodle.

Apamuekewawti, near where I live, come visit.

. . .

“Ankita’si (I think)”

.

A thought is to catch an idea

Between two minds.

Swinging to and fro

From English to Native,

Which one will I create, fulfill

Which one to roll along until arriving

To settle, still.

.

I know, my mind says to me

I know, try Mi’kmaw…

Ankite’tm

Na kelu’lk we’jitu (I find beauty)

Ankite’tm

Me’ we’jitutes (I will find more)

Ankita’si me’ (I think some more)

.

We’jitu na!*

.

*We’jitu na! – I find!

. . .

“Plawej and L’nui’site’w” (Partridge and Indian-Speaking Priest)

.

Once there was an Indian-speaking priest

Who learned Mi’kmaw from his flock.

He spoke the language the best he knew how

But sometimes got stuck.

They called him L’nui’site’w out of respect to him

And loving the man, he meant a lot to them.

At specific times he heard their confessions

They followed the rules, walking to the little church.

A widow woman was strolling through the village

On her way there, when one hunter gave her a day-old plawej

She took the partridge, putting it inside her coat

Thanking the couple, going her way.

At confession, the priest asked, “What is the smell?”

In Mi’kmaw she said, “My plawej.”

He gave blessing and sent her on her way.

The next day he gave a long sermon, ending with the words

“Keep up the good lives you are leading,

but wash your plawejk.”

The women giggled, he never knew why.

To this day there is a saying, they laugh and cry.

Whatever you do, wherever you go,

Always wash your plawejk.

. . .

“I Washed His Feet”

.

In early morning she burst into my kitchen. “I got something to

tell you, I was disrespectful to him,” she said. “Who were you

disrespectful to?” I asked. “Se’sus*,” she said. I was overwhelmed

by her statement. Caroline is my second youngest.

How in the world can one be disrespectful to someone we

never see? It was in a dream, there were three knocks on the

door. I opened the door, “Oh my God you’re here.” He came in

but stood against the wall. “I do not want to track dirt on your

floor,” he said. I told him not to mind the floor but come in, that

tea and lu’sknikn (bannock) will be ready in a moment. He ate and

thanked me… But then he asked if I would wash his feet, he

looked kind and normal, but a bit tired. In the dream, she said, I

took an old t-shirt and wet it with warm water and washed his

feet, carefully cleaning them, especially between his toes. I

wiped them off and put his sandals back on. After I was finished

I put the TV on, he leaned forward looking at the television.

His hair fell forward, he pushed it away from his face. I

removed a tendril away from his eye. “I am tired of my hair,”

he said. “Why don’t you wear a ponytail or have it braided?”

He said all right but asked me to teach him how to braid. I

stood beside him and touched his soft hair and saw a tear in

his eye, using my pinky finger to wipe the tear away. He smiled

gently. I then showed him how to braid his hair, guiding his

hands on how it was done. He caught on real easy. He was

happy. He thanked me for everything. You are welcome any

time you want to visit. He smiled as he walked out. He is just

showing us he is around at any time, even in 1997.

I was honoured to hear the story firsthand.

.

* Se’sus – Jesus

. . .

“Apiksiktuaqn (To forgive, be forgiven)”

.

A friend of mine in Eskasoni Reservation

Entered the woods and fasted for eight days.

I awaited the eight days to see him

I wanted to know what he learned from the sune’wit.

To my mind this is the ultimate for a cause

Learning the ways, an open door, derive.

At the time he did it, it was for

The people, the oncoming pow-wow

The journey to know, rationalize, spiritual growth.

When he drew near, a feeling like a parent on me

He was my son, I wanted to listen.

He talked fast, at times with a rush of words

As if to relate all, but sadness took over.

I hugged him and said, “Don’t talk if it is too sad.”

The spell was broken, he could say no more.

The one thing I heard him say, “Apiksiktuaqn nuta’ykw”,

For months it stayed on my mind.

Now it may go away as I write

Because this is the past, the present, the future.

.

I wish this would happen to all of us

Unity then will be the world over

My friend carried a message

Let us listen.

.

sune’wit – to fast, abstain from food

Apiksiktuaqn nuta’ykw – To forgive, be forgiven.

.

All of the above poems – from Rita Joe’s 1999 collection We are the Dreamers,

(published by Breton Books, Wreck Cove, Nova Scotia)

. . . . .

The following is a selection from the 26 numbered poems of Poems of Rita Joe

(published in 1978 by Abanaki Press, Halifax, Nova Scotia)

.

6

.

Wen net ki’l?

Pipanimit nuji-kina’muet ta’n jipalk.

Netakei, aq i’-naqawey;

Koqoey?

.

Ktikik nuji-kina’masultite’wk kimelmultijik.

Na epas’si, taqawajitutm,

Aq elui’tmasi

Na na’kwek.

.

Espi-kjijiteketes,

Ma’jipajita’siw.

Espitutmikewey kina’matneweyiktuk eyk,

Aq kinua’tuates pa’ qlaiwaqnn ni’n nikmaq.

.

Who are you?

Question from a teacher feared.

Blushing, I stammered

What?

.

Other students tittered.

I sat down forlorn, dejected,

And made a vow

That day

.

To be great in all learnings,

No more uncertain.

My pride lives in my education,

And I will relate wonders to my people.

. . .

10

.

Ai! Mu knu’kwaqnn,

Mu nuji-wi’kikaqnn,

Mu weskitaqawikasinukul kisna

mikekni-napuikasinukul

Kekinua’tuenukul wlakue’l

pa’qalaiwaqnn.

.

Ta’n teluji-mtua’lukwi’tij nuji-

kina’mua’tijik a.

.

Ke’ kwilmi’tij,

Maqamikewe’l wisunn,

Apaqte’l wisunn,

Sipu’l;

Mukk kas’tu mikuite’tmaqnmk

Ula knu’kwaqnn.

.

Ki’ welaptimikl

Kmtne’l samqwann nisitk,

Kesikawitkl sipu’l.

Ula na kis-napui’kmu’kl

Mikuite’tmaqanminaq.

Nuji-kina’masultioq,

we’jitutoqsip ta’n kisite’tmekl

Wisunn aq ta’n pa’-qi-klu’lk,

Tepqatmi’tij L’nu weja’tekemk

weji-nsituita’timk.

.

Aye! no monuments,

No literature,

No scrolls or canvas-drawn pictures

Relate the wonders of our yesterday.

.

How frustrated the searchings

of the educators.

.

Let them find

Land names,

Titles of seas,

Rivers;

Wipe them not from memory.

These are our monuments.

.

Breathtaking views –

Waterfalls on a mountain,

Fast flowing rivers.

These are our sketches

Committed to our memory.

Scholars, you will find our art

In names and scenery,

Betrothed to the Indian

since time began.

. . .

14

.

Kiknu na ula maqmikew

Ta’n asoqmisk wju’sn kmtnji’jl

Aq wastewik maqmikew

Aq tekik wju’sn.

.

Kesatm na telite’tm L’nueymk,

Paqlite’tm, mu kelninukw koqoey;

Aq ankamkik kloqoejk

Wejkwakitmui’tij klusuaqn.

Nemitaq ekil na tepknuset tekik wsiskw

Elapekismatl wta’piml samqwan-iktuk.

.

Teli-ankamkuk

Nkutey nike’ kinu tepknuset

Wej-wskwijnuulti’kw,

Pawikuti’kw,

Tujiw keska’ykw, tujiw apaji-ne’ita’ykw

Kutey nike’ mu pessipketenukek

iapjiweyey.

.

Mimajuaqnminu siawiaq

Mi’soqo kikisu’a’ti’kw aq nestuo’lti’kw.

Na nuku’ kaqiaq.

Mu na nuku’eimukkw,

Pasik naqtimu’k

L’nu’ qamiksuti ta’n mu nepknukw.

.

Our home is in this country

Across the windswept hills

With snow on fields.

The cold air.

.

I like to think of our native life,

Curious, free;

And look at the stars

Sending icy messages.

My eyes see the cold face of the moon

Cast his net over the bay.

.

It seems

We are like the moon –

Born,

Grow slowly,

Then fade away, to reappear again

In a never-ending cycle.

.

Our lives go on

Until we are old and wise.

Then end.

We are no more,

Except we leave

A heritage that never dies.

. . .

19

.

Klusuaqnn mu nuku’ nuta’nukul

Tetpaqi-nsitasin.

Mimkwatasik koqoey wettaqne’wasik

L’nueyey iktuk ta’n keska’q

Mu a’tukwaqn eytnukw klusuaqney

panaknutk pewatmikewey

Ta’n teli-kjijituekip seyeimik

.

Espe’k L’nu’qamiksuti,

Kelo’tmuinamitt ajipjitasuti.

Apoqnmui kwilm nsituowey

Ewikasik ntinink,

Apoqnmui kaqma’si;

Pitoqsi aq melkiknay.

.

Mi’kmaw na ni’n;

Mukk skmatmu piluey koqoey wja’tuin.

.

Words no longer need

Clear meanings.

Hidden things proceed from a lost legacy.

No tale in words bares our desire, hunger,

The freedom we have known.

.

A heritage of honour

Sustains our hopes.

Help me search the meaning

Written in my life,

Help me stand again

Tall and mighty.

.

Mi’kmaw I am;

Expect nothing else from me.

Rita Joe, born Rita Bernard in 1932, was a poet, a writer, and a human rights activist. Born in Whycocomagh, Nova Scotia, Canada, she was raised in foster homes after being orphaned in 1942. She was educated at Shubenacadie Residential School where she learned English – and that experience was also the impetus for writing a good number of her poems. (“I Lost My Talk” is about having her Mi’kmaq language denied at school.) While identity-erasure was part of her Canadian upbringing, still she managed in her writing – and in her direct, in-person activism – to promote compassion and cooperation between Peoples. Rita married Frank Joe in 1954 and together they raised ten children at their home in The Eskasoni First Nation, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. It was in her thirties, in the 1960s, that Joe began to write poetry so as to counteract the negative images of Native peoples found in the books that her children read. The Poems of Rita Joe, from 1978, was the first published book of Mi’kmaq poetry by a Mi’kmaw author. Rita Joe died in 2007, at the age of 75, after struggling with Parkinson’s Disease. Her daughters found a revision of her last poem “October Song” on her typewriter. The poem reads: “On the day I am blue, I go again to the wood where the tree is swaying, arms touching you like a friend, and the sound of the wind so alone like I am; whispers here, whispers there, come and just be my friend.”

. . . . .

Pauline Johnson / “Tekahionwake”: “Let her be natural”

Posted: April 11, 2013 Filed under: English, Pauline Johnson, Pauline Johnson's "Flint & Feather" Comments Off on Pauline Johnson / “Tekahionwake”: “Let her be natural”

ZP_E. Pauline Johnson gathered together her complete poems, though others have since been discovered, for publication in 1912, the year before her death. In her Author’s Forward to Flint and Feather she writes: This collection of verse I have named Flint and Feather because of the association of ideas. Flint suggests the Red man’s weapons of war, it is the arrow tip, the heart-quality of mine own people, let it therefore apply to those poems that touch upon Indian life and love. The lyrical verse herein is as a Skyward floating feather, Sailing on summer air. And yet that feather may be the eagle plume that crests the head of a warrior chief; so both flint and feather bear the hall-mark of my Mohawk blood._Book jacket shown here is from a 1930s edition of Flint and Feather.

Pauline Johnson / “Tekahionwake”

(1861 – 1913, born at Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation, Ontario, Canada)

.

“The Cattle Thief”

.

They were coming across the prairie, they were

galloping hard and fast;

For the eyes of those desperate riders had sighted

their man at last –

Sighted him off to Eastward, where the Cree

encampment lay,

Where the cotton woods fringed the river, miles and

miles away.

Mistake him? Never! Mistake him? the famous

Eagle Chief!

That terror to all the settlers, that desperate Cattle

Thief –

That monstrous, fearless Indian, who lorded it over

the plain,

Who thieved and raided, and scouted, who rode like

a hurricane!

But they’ve tracked him across the prairie; they’ve

followed him hard and fast;

For those desperate English settlers have sighted

their man at last.

.

Up they wheeled to the tepees, all their British

blood aflame,

Bent on bullets and bloodshed, bent on bringing

down their game;

But they searched in vain for the Cattle Thief: that

lion had left his lair,

And they cursed like a troop of demons – for the women

alone were there.

“The sneaking Indian coward,” they hissed; “he

hides while yet he can;

He’ll come in the night for cattle, but he’s scared

to face a man.”

“Never!” and up from the cotton woods rang the

voice of Eagle Chief;

And right out into the open stepped, unarmed, the

Cattle Thief.

Was that the game they had coveted? Scarce fifty

years had rolled

Over that fleshless, hungry frame, starved to the

bone and old;

Over that wrinkled, tawny skin, unfed by the

warmth of blood.

Over those hungry, hollow eyes that glared for the

sight of food.

.

He turned, like a hunted lion: “I know not fear,”

said he;

And the words outleapt from his shrunken lips in

the language of the Cree.

“I’ll fight you, white-skins, one by one, till I

kill you all,” he said;

But the threat was scarcely uttered, ere a dozen

balls of lead

Whizzed through the air about him like a shower

of metal rain,

And the gaunt old Indian Cattle Thief dropped

dead on the open plain.

And that band of cursing settlers gave one

triumphant yell,

And rushed like a pack of demons on the body that

writhed and fell.

“Cut the fiend up into inches, throw his carcass

on the plain;

Let the wolves eat the cursed Indian, he’d have

treated us the same.”

A dozen hands responded, a dozen knives gleamed

high,

But the first stroke was arrested by a woman’s

strange, wild cry.

And out into the open, with a courage past

belief,

She dashed, and spread her blanket o’er the corpse

of the Cattle Thief;

And the words outleapt from her shrunken lips in

the language of the Cree,

“If you mean to touch that body, you must cut

your way through me.”

And that band of cursing settlers dropped

backward one by one,

For they knew that an Indian woman roused, was

a woman to let alone.

And then she raved in a frenzy that they scarcely

understood,

Raved of the wrongs she had suffered since her

earliest babyhood:

“Stand back, stand back, you white-skins, touch

that dead man to your shame;

You have stolen my father’s spirit, but his body I

only claim.

You have killed him, but you shall not dare to

touch him now he’s dead.

You have cursed, and called him a Cattle Thief,

though you robbed him first of bread –

Robbed him and robbed my people – look there, at

that shrunken face,

Starved with a hollow hunger, we owe to you and

your race.

What have you left to us of land, what have you

left of game,

What have you brought but evil, and curses since

you came?

How have you paid us for our game? how paid us

for our land?

By a book, to save our souls from the sins you

brought in your other hand.

Go back with your new religion, we never have

understood

Your robbing an Indian’s body, and mocking his

soul with food.

Go back with your new religion, and find – if find

you can –

The honest man you have ever made from out a

starving man.

You say your cattle are not ours, your meat is not

our meat;

When you pay for the land you live in, we’ll pay

for the meat we eat.

Give back our land and our country, give back our

herds of game;

Give back the furs and the forests that were ours

before you came;

Give back the peace and the plenty. Then come

with your new belief,

And blame, if you dare, the hunger that drove him to

be a thief.”

. . .

“A Cry from an Indian Wife” (1885)

.

My forest brave, my Red-skin love, farewell;

We may not meet to-morrow; who can tell

What mighty ills befall our little band,

Or what you’ll suffer from the white man’s hand?

Here is your knife! I thought ’twas sheathed for aye.

No roaming bison calls for it to-day;

No hide of prairie cattle will it maim;

The plains are bare, it seeks a nobler game:

‘Twill drink the life-blood of a soldier host.

Go; rise and strike, no matter what the cost.

Yet stay. Revolt not at the Union Jack,

Nor raise Thy hand against this stripling pack

Of white-faced warriors, marching West to quell

Our fallen tribe that rises to rebel.

They all are young and beautiful and good;

Curse to the war that drinks their harmless blood.

Curse to the fate that brought them from the East

To be our chiefs – to make our nation least

That breathes the air of this vast continent.

Still their new rule and council is well meant.

They but forget we Indians owned the land

From ocean unto ocean; that they stand

Upon a soil that centuries agone

Was our sole kingdom and our right alone.

They never think how they would feel to-day,

If some great nation came from far away,

Wresting their country from their hapless braves,

Giving what they gave us – but wars and graves.

Then go and strike for liberty and life,

And bring back honour to your Indian wife.

Your wife? Ah, what of that, who cares for me?

Who pities my poor love and agony?

What white-robed priest prays for your safety here,

As prayer is said for every volunteer

That swells the ranks that Canada sends out?

Who prays for vict’ry for the Indian scout?

Who prays for our poor nation lying low?

None – therefore take your tomahawk and go.

My heart may break and burn into its core,

But I am strong to bid you go to war.

Yet stay, my heart is not the only one

That grieves the loss of husband and of son;

Think of the mothers o’er the inland seas;

Think of the pale-faced maiden on her knees;

One pleads her God to guard some sweet-faced child

That marches on toward the North-West wild.

The other prays to shield her love from harm,

To strengthen his young, proud uplifted arm.

Ah, how her white face quivers thus to think,

Your tomahawk his life’s best blood will drink.

She never thinks of my wild aching breast,

Nor prays for your dark face and eagle crest

Endangered by a thousand rifle balls,

My heart the target if my warrior falls.

O! coward self I hesitate no more;

Go forth, and win the glories of the war.

Go forth, nor bend to greed of white men’s hands,

By right, by birth we Indians own these lands,

Though starved, crushed, plundered, lies our nation low…

Perhaps the white man’s God has willed it so.

.

Editor’s note: “the war” referred to in Johnson’s poem is The NorthWest Rebellion (or NorthWest Resistance) of 1885, led by Louis Riel.

. . .

“The Wolf”

.

Like a grey shadow lurking in the light,

He ventures forth along the edge of night;

With silent foot he scouts the coulie’s rim

And scents the carrion awaiting him.

His savage eyeballs lurid with a flare

Seen but in unfed beasts which leave their lair

To wrangle with their fellows for a meal

Of bones ill-covered. Sets he forth to steal,

To search and snarl and forage hungrily;

A worthless prairie vagabond is he.

Luckless the settler’s heifer which astray

Falls to his fangs and violence a prey;

Useless her blatant calling when his teeth

Are fast upon her quivering flank–beneath

His fell voracity she falls and dies

With inarticulate and piteous cries,

Unheard, unheeded in the barren waste,

To be devoured with savage greed and haste.

Up the horizon once again he prowls

And far across its desolation howls;

Sneaking and satisfied his lair he gains

And leaves her bones to bleach upon the plains.

. . .

“The Indian Corn Planter”

.

He needs must leave the trapping and the chase,

For mating game his arrows ne’er despoil,

And from the hunter’s heaven turn his face,

To wring some promise from the dormant soil.

.

He needs must leave the lodge that wintered him,

The enervating fires, the blanket bed–

The women’s dulcet voices, for the grim

Realities of labouring for bread.

.

So goes he forth beneath the planter’s moon

With sack of seed that pledges large increase,

His simple pagan faith knows night and noon,

Heat, cold, seedtime and harvest shall not cease.

.

And yielding to his needs, this honest sod,

Brown as the hand that tills it, moist with rain,

Teeming with ripe fulfilment, true as God,

With fostering richness, mothers every grain.

. . .

Emily Pauline Johnson (1861 – 1913) took on the Mohawk-language name Tekahionwake (meaning “double life”) around the time, as a young adult, she became aware of her ability not only as a woman who was writing poetry but also as a performer. Words such as transgressive and performativity – belovéd of academics in the 21st century – were words she mightn’t have known yet she “enacted” their meanings – and without the cadre of professionals to chatter about “who she really was”. And who was she – really? Well, she was complex – in some ways uncategorizable. A young woman who helped to support her widowed mother (her father, Brantford Six Nations Chief George Henry Martin Johnson (Onwanonsyshon) died in 1884) via the publication of her sentimental-exotic yet oddly-truthful poems; whose attachment to her father’s Native-ness was deeply felt during the onset of the Erasure Period chapter in First-Nations history in that New Nation – Canada. Pauline Johnson was mixed-race – Mohawk father of chieftain lineage, mother (Emily Susana Howells), a kind of English “rose” in a young British-colonial country. Enamoured of The Song of Hiawatha, and of Wacousta – Pauline was yet entranced by and deeply listened to the Native oral histories of John Smoke Johnson, her paternal grandfather. This was Pauline Johnson.

From about 1892 until 1909, Johnson, aided by impresario Frank Yeigh, toured as “The Mohawk Princess”, orating passionate poem-recitals while decked out in a mish-mashed Native costume which presented to Late-Victorian and Edwardian-era audiences a glamorous spectacle of Indian-ness. In the July/August 2012 issue of the Canadian magazine The Walrus, Emily Landau writes: “…and although her (Johnson’s) branding played into the stereotypes, her stories broke (the audiences) down.” Poems such as “The Indian Thief” and “A Cry from an Indian Wife” (both featured here) gave Native women a voice – using Victorian melodrama to present brief morality tales where what the Native woman says is right. Landau remarks that Johnson performed with “a mix of poise and campy histrionics. In a trademark flourish, she (would) shed the buckskin during intermission, returning in a staid silk evening gown and pumps, eliciting gasps from spectators as they marveled at the transformation. The two modes of dress served as an external manifestation of Johnson’s own dual identity: her (other) name, Tekahionwake, meant “double life” in Mohawk.”

Landau continues: “In an 1892 essay entitled “A Strong Race Opinion: On the Indian Girl in Modern Fiction,” Johnson called out white writers for their generic, latently racist depictions of Native femininity. Without fail, she says, the Indian girl, always named Winona or some such, has no tribal specificity, merely serving as a self-sacrificing, mentally unhinged outlet for the white hero’s magnanimity. Johnson entreated writers to give their “Indian girl” characters the same dignity and distinction as they did their white characters. “Let the Indian girl in fiction develop from the ‘dog-like,’ ‘fawn-like,’ ‘deer-footed,’ ‘fire-eyed,’ ‘crouching,’ ‘submissive’ book heroine into something of the quiet, sweet womanly woman if she is wild, or the everyday, natural, laughing girl she is if cultivated and educated; let her be natural,” she wrote, “even if the author is not competent to give her tribal characteristics.”

In her own act, Johnson drew from the dominant white theatrical modes. Melodrama, the most popular form in the late nineteenth century, was characterized by an excess of spectacle, histrionic gestures, and amplified emotions. With her over-the-top theatrics, she was a hit with crowds hungry for sentiment. One of her most popular stories, “A Red Girl’s Reasoning,” tells of a young half-Indian woman who leaves her husband after he refuses to recognize the legitimacy of her nation’s rituals; another heroine, the half-Cree Esther of “As It Was in the Beginning,” kills her faithless white lover.”

Johnson stopped touring in 1909. She had developed breast cancer, and worsening health led to early retirement. Settling in Vancouver, she still wrote – adapting stories as told to her by her friend, Squamish Chief Joseph Capilano. Johnson died in 1913; a monument – and her ashes – are in Vancouver’s Stanley Park.

And – we quote Landau again: “…Enterprising as she was, Johnson was also an idealist. Her proud biracial identity, within which her Aboriginal and European selves peacefully coexisted, constituted an anomaly in an era when race was considered a fixed trait. The unified persona she presented onstage, nurtured in her childhood and reflected in her writings, represented more than just an amplified, campy theatrical ruse: it was a vision of what she imagined for Canada. Surveying Canada’s beaming multiculturalism today, flawed as it may be, Johnson seems like quite an oracle.”

.

We wish to thank editor Emily Landau of Toronto Life for her critical analysis of the career of Pauline Johnson.

. . . . .