Maxwell Bodenheim: poemas: “Para mi enemigo”, “Para un hombre”, “Para alguien muerto”

Posted: March 25, 2016 Filed under: English, Maxwell Bodenheim, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: Poemas para El Viernes Santo, Poems for Good Friday Comments Off on Maxwell Bodenheim: poemas: “Para mi enemigo”, “Para un hombre”, “Para alguien muerto”Maxwell Bodenheim

(1892-1954, EE. UU., poeta y escritor de literatura barata, bohemio, teporocho, mendigo, víctima de homicidio)

Para mi enemigo

.

Desprecio mis amigos más que te desprecio.

Yo mismo, lo entendiera pero ellos se pararon ante los espejos

y los pintaron con imágenes de las virtudes que ansié.

Llegaste con un cincel lo más afilado, rascando la pintura falsa.

Pues me conocí y me detesté – pero no te detesté –

porque los vistazos de ti en las gafas que descubriste

me enseñaron las virtudes cuyas imágenes destruiste.

. . .

Para un hombre

.

Maestro de equilibrio serio,

eres un Cristo hecho delicado

por muchos siglos de meditación perpleja.

Curvas un viejo mito hacia una espada pacífica,

como un sonámbulo desafiando

un sueño que le dio forma a él.

Con una insistencia suave y anticuada

colocas la mano de tu criatura en el universo

y delineas una sonrisa de amor dentro de sus profundidades.

Pero los hombres-espantapájaros girandos que están

hechos de algo que elude su vista

tengan la sencillez sorprendente de tu sonrisa.

.

Una vez por mil años

la quietud se materializa en una forma que

podemos crucificar.

. . .

Para alguien muerto

.

Yo caminaba por la colina

y el viento, solemnemente ebrio a causa de tu presencia,

se tambaleó contra mí.

Me encorvé para interrogar a una flor,

y flotaste entre mis dedos y los pétalos,

amarrándolos juntos.

Corté una hoja de su árbol

y una gota de agua en esa jarra verde

ahuecaba una pizca cazada de tu sonrisa.

Todas las cosas de mis alrededores se remojaron de tu recuerdo

y tiritaban mientras intentaron decírmelo.

. . .

Maxwell Bodenheim

(1892-1954, American poet, pulp-fiction author, bohemian, drunk, beggar, homicide victim)

To an enemy

.

I despise my friends more than you.

I would have known myself but they stood before the mirrors

And painted on them images of the virtues I craved.

You came with sharpest chisel, scraping away the false paint.

Then I knew and detested myself, but not you,

For glimpses of you in the glasses you uncovered

Showed me the virtues whose images you destroyed.

. . .

To a man

.

Master of earnest equilibrium,

You are a Christ made delicate

By centuries of baffled meditation.

You curve an old myth to a peaceful sword,

Like some sleep-walker challenging

The dream that gave him shape.

With gentle, antique insistence

You place your child’s hand on the universe

And trace a smile of love within its depths.

And yet, the whirling scarecrow men made

Of something that eludes their sight,

May have the startling simplicity of your smile.

.

Once every thousand years

Stillness fades into a shape

That men may crucify.

. . .

To one dead

.

I walked upon a hill

And the wind, made solemnly drunk with your presence,

Reeled against me.

I stooped to question a flower,

And you floated between my fingers and the petals,

Tying them together.

I severed a leaf from its tree

And a water-drop in the green flagon

Cupped a hunted bit of your smile.

All things about me were steeped in your remembrance

And shivering as they tried to tell me of it.

. . . . .

Judas Iscariote: dos ángulos poéticos

Posted: March 24, 2016 Filed under: English, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Judas Iscariote: dos ángulos poéticosDon Tyson

Judas Iscariote

.

Judas,

hijo de Simón,

uno entre los doce.

Dicen que

estuvo motivado por la avaricia;

que fue un insatisfecho

– ¿o quizás no?

El traidor de Cristo,

el instrumental del diablo

– ¿o utilizado por Dios?

El premio de su fechoría: suicidio

y una tumba en un campo de sangre.

Judas:

vilipendiado;

maldito para siempre;

aborrecido por todos

excepto Dios

– que lo mandó.

. . .

Daniel Thomas Moran

La última cena de Judas Iscariote

.

Judas hizo lo correcto;

esperó que completaron el postre;

que el Salvador de Humanidad

acabe su trozo de pastel – y café.

.

Sabía que su Maestro

no estaría para nada contento – en absoluto.

.

Mientras sus hermanos tontos

compartían un vaso de oporto,

él – cuyo nombre habría llamado traido – dijo:

Declinaré, pero gracias.

.

Judas fue correcto

pero odiaba los adioses largos.

Yo te veré en el jardín más tarde

– hay un cuate en el pueblo que me debe unas monedas.

.

Y El Señor habló:

Mañana tendré un largo día.

Entonces, déjenme relatar un chiste más,

pues demos el día por terminado.

.

Y Jesús se inclinó en sus codos y preguntó:

¿Han oído ustedes el cuento del hombre que piensa que ha visto a un fantasma?

. . . . .

Don Tyson

Judas Iscariot

.

Judas,

son of Simon,

one of the twelve.

it is said

he was driven by greed,

a malcontent,

or was he?

the betrayer of Christ,

a tool of the devil,

or used of God.

the reward for

his misdeed,

suicide;

a grave in

a field of blood.

Judas, vilified,

forever accursed,

hated by all

but God,

who sent him.

. . .

Daniel Thomas Moran

The Last Supper of Judas Iscariot

.

Judas was right

to wait until after dessert.

If only for the Saviour of Mankind

to finish his coffee and pie.

.

He knew his Master

would not be happy

about any of it.

.

While his dimwit brothers

shared a glass of Port,

He, whose name would

be called betrayer, said

He would pass, thanks.

.

Judas was right, but

He hated long goodbyes:

I’ll see you in the garden, later.

There’s a guy in town

who owes me money.

.

The Lord spoke:

I’ve got a long day tomorrow.

How about one more joke,

And we’ll call it a night.

.

Then he leaned onto

his elbows and he asked:

Did you hear the one

about the guy who thinks

he’s seen a ghost?

. . . . .

Jorge Valdés Díaz-Vélez: “February Song” and “Living Nature”

Posted: March 23, 2016 Filed under: English, Jorge Valdés Díaz-Vélez, Spanish Comments Off on Jorge Valdés Díaz-Vélez: “February Song” and “Living Nature”Jorge Valdés Díaz-Vélez

Canción de febrero

.

sobre el pecho del cielo, palpitando

Jaime Gil de Biedma

.

Leve y triste la tarde se retira

contigo hacia el crepúsculo y las horas

empiezan a doler en los distantes

repliegues de la sábana. De pronto

la noche ha regresado y es difícil

no pensar en tu boca momentánea

o en las altas comarcas de tu cuerpo

en lienzos de algodón por alabanza.

Ahora que no estás, vuelvo a mirar

el rayo que dividen tus pestañas

y el estremecimiento de tu espalda

moldeándome los brazos, la sonrisa

de tu sexo en los vértigos del labio,

el instante fluvial de tu alegría.

A lo lejos respira el mar, asciende

la blanda superficie a su clausura

bajo un raso de líquidos vitrales.

La noche sin tu piel crece más honda

por las calles donde asperjas la lluvia.

En silencio te diluyes, muchacha,

con las últimas brasas que se apagan

contra el pecho del cielo, palpitando.

. . .

February Song

.

on the breast of the sky, beating

Jaime Gil de Biedma

.

Slow and sad the afternoon retires

with you toward twilight, and the hours

begin to languish in the distant

folds of the sheets. Soon night has returned

and I can hardly avoid thinking

about your fleeting mouth

or the high regions of your body

aggrandized on cotton canvases.

You are not here now; I see again

the beam that your eyelashes divide

and the shiver up and down your back

reshaping my arms for me, the smile

of your sex in vertigos of lips,

and the flowing moment of your joy.

Far away the sea breathes deep, climbing

the soft surface towards its closure

beneath a clear sky of liquid glass.

The night without your skin grows deeper

in the streets where you spatter the rain.

In silence you dissolve, my beloved,

with the last embers that extinguish

against the breast of the sky, beating.

. . .

Naturalezas vivas

.

Duermes. La noche está contigo,

la noche hermosa igual a un cuerpo

abierto a su felicidad.

Tu calidez entre las sábanas

es una flor difusa. Fluyes

hacia un jardín desconocido.

Y, por un instante, pareces

luchar contra el ángel del sueño.

Te nombro en el abrazo y vuelves

la espalda. Tu cabello ignora

que la caricia del relámpago

muda su ondulación. Escucha,

está lloviendo en la tristeza

del mundo y sobre la amargura

del ruiseñor. No abras los ojos.

Hemos tocado el fin del día.

. . .

Living Nature

.

Sleeping, night is with you,

night as beautiful as a body

open to happiness.

Your warmth under the sheets

is but a hazy bloom. You flow

toward a secret garden.

For an instant,

you seem to fight away

the angel of the dream.

I call you in the embrace and you turn back.

Your hair is unaware of

lightning that shifts its waves with a caress.

Listen,

it’s raining in the sadness of the world,

and in the grief of nightingales.

Do not open your eyes.

Thus ends the day.

. . .

Versiones al inglés de Christian Law y Sue Burke

. . .

Jorge Valdés Díaz-Vélez was born in Torreón, México, in 1955. He is considered to be a foremost poet in Ibero-American contemporary literature. He has written more than 15 books of poetry published in México, Italy and Spain, and has been included in several anthologies from Europe, North Africa and Latin America. Winner of México’s National Poetry Award Aguascalientes, Díaz-Vélez has also won the Latin- American Award Plural, and Spain‘s International Poetry Prize Miguel Hernandez-Comunidad Valenciana and the Ibero-American Poetry Prize Hermanos Machado.

. . . . .

Mary Oliver: Momentos (“Moments”)

Posted: March 22, 2016 Filed under: English, Mary Oliver, Spanish | Tags: Poemas para el Cambio de Estaciones, Poems for the change of seasons Comments Off on Mary Oliver: Momentos (“Moments”)Mary Oliver (American poet, Pulitzer Prize winner, born 1935)

Moments

.

There are moments that cry out to be fulfilled.

Like, telling someone you love them.

Or giving your money away, all of it.

.

Your heart is beating, isn’t it?

You’re not in chains, are you?

.

There is nothing more pathetic than caution

when headlong might save a life

even, possibly, your own.

. . .

Mary Oliver (Ohio, EE.UU., nac. 1935)

Momentos

.

Hay momentos que piden a gritos cumplirse.

Como, decirle a alguien que lo amas.

O dejar tu dinero, todo.

.

Tu corazón late, ¿verdad?

Estás desencadenado, ¿no es cierto?

.

No hay nada más patético que la cautela

cuando ir de cabeza puede salvar una vida

incluso, posiblemente, la tuya.

. . .

Traducción del inglés: Christopher Cummins (Irlanda, 2016)

. . . . .

Alexander Best: El primer día de la primavera: un retrato / First Day of Spring: a portrait

Posted: March 20, 2016 Filed under: Alexander Best, English, Spanish | Tags: Poemas para el Cambio de Estaciones, Poems for the change of seasons Comments Off on Alexander Best: El primer día de la primavera: un retrato / First Day of Spring: a portraitAlexander Best

El primer día de la primavera: un retrato

.

Ahora el hielo se ha derretido y está pasando el hondo deshielo.

Pero parece que nada brota hasta ahora, salvo una idea…

.

Imagina ésto:

No satisfacen las palabras – no alcanzan – aunque tenemos tantas / bastante.

La pluma, el alfabeto, la lengua – superamos el invierno con esos

pero no pueden llenar el cuento.

.

Ten empatía para los vivos

– la catarina que sobrevivió fuera de su estación;

el pájaro-cardenal y su canto desgarrador;

el mapache pesado pero ágil;

la anciana inarticulada de rabia;

la infante gorjeando con burbujas de escupitajo.

Ten empatía para objetos y cosas

– la madera macheteada;

la bocina de la tren que se dobla alto pues suaviza como viene y va;

una caja colocada al encintado con una nota vendada (“GRATIS”)

y nada de sobra excepto un platón-vidrio de microondas.

.

Vamos a dibujar lo que está en frente de nosotros

y obviaremos todas palabras.

Un lápiz o una cera, y algunas hojas de papel sin pautar.

Haremos un nuevo comienzo, sí,

y lo mostraremos esta vez – no lo diremos.

.

El sol nos vislumbra, de vez en cuando;

es brillante pero aún sin calor.

Nos sentamos en el piso.

Miramos:

botas retorcidas horribles que no podemos esperar a botar;

tazas de café abigarradas que nunca nos deshacemos;

una fea mesa y sus sillas tambaleantes;

una almohada.

.

Creemos el resto de nuestro cuento – la parte que estamos omitiendo, a menudo.

Perseveraremos la verdad, informando los hechos, con ceras en mano.

Entonces, dibuja lo que está enfrente de ti;

tú – (nosotros) – no tienes que estar listo de manera perfecta.

Hazlo ahora.

. . .

Alexander Best

First Day of Spring: a portrait

.

Now the ice is melted and a deep thaw’s underway.

Yet it seems like nothing’s growing yet,

except an idea…

.

Picture this:

Words don’t suffice, though we do have enough of them.

The pen, the alphabet, our tongue – these got us through the winter

but cannot complete the story.

.

Have empathy for the living

– the ladybug who survived out of season;

the cardinal and his heartbreaking call;

the heavy yet nimble raccoon;

the old woman inarticulate with rage;

the infant whose mouth gurgles bubbles of spit.

Have empathy for objects and things

– the hacked-away-at wooden post;

the train horn bending loud then softening as it comes and goes;

a box placed at the curb with a note taped to it (“FREE”) and

nothing left but a glass microwave platter.

.

We’ll draw what’s before us, and leave words out of it.

A pencil or crayon, and a few sheets of paper (unlined) will do.

We’re going to make a new beginning, yes,

and we’ll show this time, not tell.

.

The sun glimpses in, now and again – bright but still without heat.

We’re sitting on the floor.

We see:

awful gnarled boots we can’t wait to toss;

mismatched coffee cups that we’ll never get rid of;

an ugly table and some rickety chairs;

a pillow.

.

Let’s create the rest of our story, that part we often leave out.

We shall keep at the truth, reporting the facts with crayons in hand.

So draw what’s right in front of you;

you –( we )– don’t have to be perfectly ready.

Do it now.

. . . . .

Cinco poetas irlandeses: Cannon, Sheehan, Níc Aodha, Ní Chonchúir, Bergin

Posted: March 17, 2016 Filed under: A FEW FAVOURITES / UNA MUESTRA DE FAVORITOS, Cinco poetas irlandeses, English, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: Poetisas irlandesas Comments Off on Cinco poetas irlandeses: Cannon, Sheehan, Níc Aodha, Ní Chonchúir, BerginMoya Cannon (nac. 1956, Dunfanaghy, Condado de Donegal)

Olvidar los tulipanes

.

Hoy en la terraza

él está señalando con el bastón,

está preguntando:

¿Cuál es el nombre de esas flores?

Vacacionando en Dublín en los sesenta

ha comprado los cinco bulbos originales por una libra.

Los ha plantado, los ha fertilizado durante treinta y cinco años.

Los dividió, los almacenaba en el cobertizo sobre alambrada,

listos para plantar en hileras rectas

con sus corolas intensas de rojo y amarillo.

.

Tesoros transportados en galeones, tres siglos antes,

desde Turquía hasta Amsterdam.

Ahora es abril y ellos se balancean con el viento del condado Donegal,

encima de las hojas esbeltas de los claveles que todavía duermen.

.

Fue un hombre que cavaba surcos correctos y que recogió grosellas negras;

que enseñó a hileras de niños las partes de la oración, tiempos y declinaciones

debajo de un mapamundi de tela agrietada.

Y le encantaba enseñar el cuento de Marco Polo y de sus tíos que,

zarrapastrosos después de diez años de viaje,

volvían a casa pues rajaron el forro de sus chamarras

y se desparramaron los rubies de Catay.

.

Ahora, perdiendo primero los nombres,

él está de pie junto a su lecho de flores, preguntando:

¿Tú, cómo llamas a esas flores?

. . .

Moya Cannon (born 1956, Dunfanaghy, Co. Donegal)

Forgetting Tulips

.

Today, on the terrace, he points with his walking-stick and asks:

What do you call those flowers?

On holiday in Dublin in the sixties

he bought the original five bulbs for one pound.

He planted and manured them for thirty-five years.

He lifted them, divided them,

stored them on chicken wire in the shed,

ready for planting in a straight row,

high red and yellow cups–

.

treasure transported in galleons

from Turkey to Amsterdam, three centuries earlier.

In April they sway now, in a Donegal wind,

above the slim leaves of sleeping carnations.

.

A man who dug straight drills and picked blackcurrants;

who taught rows of children parts of speech,

tenses and declensions

under a cracked canvas map of the world–

who loved to teach the story

of Marco Polo and his uncles arriving home,

bedraggled after ten years journeying,

then slashing the linings of their coats

to spill out rubies from Cathay–

.

today, losing the nouns first,

he stands by his flower bed and asks:

What do you call those flowers?

. . .

Eileen Sheehan (nac. 1963, Scartaglin, Condado de Kerry)

Donde tú estás

.

Tú te tumbas en cualquiera cama,

te tumbas en el fondo, y el cojín acepta

el peso de tu cabeza,

el colchón recibiendo tu cuerpo como el invitado anhelado.

Te mueves durante el reposo

y las sábanas responden a tu giro;

las cobijas se adaptan y se amoldan a tu contorno.

El aire de la habitación toma el tiempo con tu respiración,

aceptando un desplazamiento mientras

yo rodeo las paredes de la ciudad que estás ‘soñando’.

.

Mis papeles

– están raídos y deshilachados al borde;

esa pintura que tengo de yo mismo – está nublándose,

manchada por la lluvia: mi cara está disolviendo enfrente de mí.

La noche te agarra en el sueño y estás aplacado por sus comodidades,

como las telas absorbiendo el sudor que despides.

Mis llantos van ignorados mientras estoy de pie por la verja,

implorando un acceso.

No hay nadie pedir ayuda mientras

te mudas una capa como te extiendes allí – roque;

mi solo testigo fiable.

.

(2009)

. . .

Eileen Sheehan (born 1963, Scartaglin, Co. Kerry)

Where you are

.

You lie down in whatever bed

you lie down in, the pillow accepting

the weight of your head, the mattress

receiving your body like a longed-for guest.

You move in your sleep and the sheets

react to your turnings, the blankets adjust,

shaping themselves to your outline.

The air

in the room keeps time with your breathing,

accepts being displaced while I circle the walls

of the city you dream.

My papers

are worn, frayed at the edges; that picture

I have of myself, clouding-over and spotted

with rain: my face is dissolving before me. The night

holds you in sleep, you are stilled by its comforts;

by the fabrics absorbing the sweat you expel.

My cries go unheeded as I stand at the gate,

pleading admittance. There is no one to turn to

as you shed a layer of your skin while you lie there,

dead to the world; my one reliable witness.

. . .

© 2009, Eileen Sheehan

. . .

Colette Níc Aodha (nac. 1967, Shrule, Condado de Mayo)

Ruinas

.

Buscando en los annales

por los acontecimientos que sucedieron

durante una época diferente;

recreando el Tiempo en las ruinas antiguas,

tocando la música de los ancianos,

pasos de baile de los ascendientes.

.

Anoche yo visité al lugar de mi padre

pero encontré la derrota de

una casa confeccionada de piel

mientras una otra ha estado dado forma

de abajo por sus huesos.

. . .

Colette Níc Aodha (born 1967, Shrule, Co. Mayo)

Ruins

.

Searching the annals

for events which took place

in a different era

Recreating time in old ruins

Playing ancient music

Dancing steps of our ancestors

Last night I visited my father’s place

but found a ruin of a house

crafted from skin

as another was shaped

below from his bone.

. . .

Nuala Ní Chonchúir (nac. 1970, Dublin)

Enojo

.

La luna está magullada esta noche.

Moreteada y hinchada está – pero

fanfarronea sobre nosotros

y jala júbilo a la rasca.

.

Luna de sebo, luna electrizante,

ella carga el cielo, y

es un foco descarado por encima de los árboles sazonados de escarcha.

.

Y aquí abajo, donde añoran nuestros ojos,

nos arrastramos a la iglesia en la plaza, y

hacemos las paces uno al otro – en el canto.

.

(2011)

. . .

Nuala Ní Chonchúir (born 1970, Dublin)

Anger

.

The moon is battered tonight, bruised and swollen,

but she swanks above us, bringing joy to the chill.

.

Tallow-moon, electric-moon, she shoulders the sky,

a brazen spotlight over trees salted with frost.

.

And down here, eyes aching, we creep to the church

on the square, make peace with each other in song.

. . .

from: The Juno Charm (2011)

. . .

Tara Bergin (nac. 1975, Dublin)

Bandera roja

.

Una vez uno de ellos me mostró cómo:

Giras esta mano (la derecha) para agarrar la culata.

Giras esta mano (la izquierda) para agarrar el cañon.

Tocó mi rodilla,

y oculté mi sorpresa;

pero ahora ha cambiado su canción.

.

36,37,38.9

.

Tengo fiebre, golondrina, estoy enferma.

Su bandera ondula roja,

la puedo oír desde mi ventana,

la escucho raída como un trapo rojo rasgado.

Ve por él, pajarito,

ve y diles ¡peligro! ¡peligro!

.

Lo llevaré como Vestido Dominical.

Lo llevaré cruzando el páramo

donde practican con sus pistolas.

.

38.9,37,36

.

Qué avergonzados estarán

de lastimar a una muchacha

joven y bonita como yo.

. . .

Tara Bergin (born 1975, Dublin)

Red Flag

.

Once one of them showed me how to:

You turn this (the right) hand to grasp the stock.

You turn this (the left) hand to grasp the barrel.

He touched my knee,

and I hid my surprise –

but now he’s changed his tune.

.

36,37,38.9

.

I’ve a fever, little sparrow, I am sick.

Their flag is flying red,

I can hear it from my window,

I hear it tattered like a torn red rag.

Go and get it, little bird,

go and tell them danger! danger!

.

I will wear it as my Sunday Dress.

I’ll wear it walking on the moor

where they practise with their guns.

.

38.9,37,36

.

How ashamed they’ll be

to hurt a young and pretty

girl like me.

. . .

Versiones en español del inglés por Alexander Best, excepto Bandera Rojo de Tara Bergin: traducido por Juana Adcock (nac. 1982, Monterrey, Mx.)

. . . . .

El Día Internacional de la Mujer: Poemas / International Women’s Day: Poems

Posted: March 5, 2016 Filed under: English, Fehmida Riaz, Halima Xudoyberdiyeva, Marge Piercy, Mina Loy, Qiu Jin, Spanish, Uzbek, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on El Día Internacional de la Mujer: Poemas / International Women’s Day: Poems. . .

Qiu Jin ( 秋瑾 1875-1907, Chinese revolutionary and poet)

Capping Rhymes With Sir Shih Ching From Sun’s Root Land

.

Don’t tell me women

are not the stuff of heroes –

I alone rode over the East Sea’s

winds for ten thousand leagues.

My poetic thoughts ever expand,

like a sail between ocean and heaven.

I dreamed of your three islands,

all gems, all dazzling with moonlight.

I grieve to think of the bronze camels,

guardians of China, lost in thorns.

Ashamed, I have done nothing;

not one victory to my name.

I simply make my war horse sweat.

Grieving over my native land

hurts my heart. So tell me:

how can I spend these days here?

A guest enjoying your spring winds?

. . .

Qiu Jin

Crimson Flooding into the River

(Translation from Mandarin: Michael A. Mikita III)

.

Just a short stay at the Capital

But it is already the mid-autumn festival

Chrysanthemums infect the landscape

Fall is making its mark

The infernal isolation has become unbearable here

All eight years of it make me long for my home

It is the bitter guile of them forcing us women into femininity

–We cannot win!

Despite our ability, men hold the highest rank

But while our hearts are pure, those of men are rank

My insides are afire in anger at such an outrage

How could vile men claim to know who I am?

Heroism is borne out of this kind of torment

To think that so putrid a society can provide no camaraderie

Brings me to tears!

. . .

Mina Loy (1882-1966, Anglo-American modernist poet)

Religious Instruction

.

This misalliance

follows the custom

for female children

to adhere to maternal practices

.

while the atheist father presides over

the prattle of the churchgoer

with ironical commentary from his arm-chair.

.

But by whichever

religious route

to brute

reality

our forebears speed us

.

there is often a pair

of idle adult

accomplices in duplicity

to impose upon their brood

.

an assumed acceptance

of the grace of God

defamed as human megalomania

.

seeding the Testament

with inconceivable chastisement,

.

and of Christ

who

come with his light

of toilless lilies

To say “fear

not, it is I”

wanting us to be fearful;

.

He who bowed the ocean tossed

with holy feet

which supposedly dead

.

are suspended over head

neatly crossed in anguish

wounded with red

varnish.

.

From these

slow-drying bloods of mysticism

mysteriously

the something-soul emerges

miserably,

.

and instinct (of economy)

in every race

for reconstructing débris

has planted an avenging face

in outer darkness.

…..

The lonely peering eye

of humanity

looked into the Néant

and turned away.

…..

Ova’s consciousness

impulsive to commit itself to justice

—to arise and walk

its innate straight way

out of the

accident of circumstance—

.

collects the levitate chattels

of its will and makes for the

magnetic horizon of liberty

with the soul’s foreverlasting

opposition

to disintegration.

.

So this child of Exodus

with her heritage of emigration

often

“sets out to seek her fortune”

in her turn

trusting to terms of literature

dodging the breeders’ determination

not to return “entities sent on consignment”

by their maker Nature

except in a condition

of moral

effacement;

Lest Paul and Peter

never

notice the creatures

ever had had Fathers

and Mothers.

.

They were disgraced in their duty

should such spirits

take an express passage

through the family bodies

to arrive at Eternity

as lovely as they originally

promised.

.

So on whatever days

she chose to “run away”

the very

street corners of Kilburn

close in upon Ova

to deliver her

into the hands of her procreators.

.

Oracle of civilization:

‘Thou shalt not live by dreams alone

but by every discomfort

that proceedeth out of

legislation’.

. . .

Mina Loy’s “Religious Instruction” from Lunar Baedeker and Times-Tables copyright The Jargon Society, 1958.

. . .

Mina Loy

No hay Vida o Muerte

.

No hay vida ni muerte,

sólo actividad.

Y en lo absoluto

no hay declive.

No hay amor ni deseo,

sólo la tendencia.

Quien quiera poseer

es una no entidad.

No hay primero ni último,

sólo igualdad.

Y quien quiera dominar

es uno más en la totalidad.

No hay espacio ni tiempo,

sólo intesidad.

Y las cosas dóciles

no tienen inmensidad.

.

Traducción del inglés: Michelle (de MujerPalabra)

. . .

Mina Loy

There is no Life or Death

.

There is no Life or Death

Only activity

And in the absolute

Is no declivity.

There is no Love or Lust

Only propensity

Who would possess

Is a nonentity.

There is no First or Last

Only equality

And who would rule

Joins the majority.

There is no Space or Time

Only intensity,

And tame things

Have no immensity.

. . .

Marge Piercy (nac.1936, EE.UU. / poeta, novelista, activista social)

Ser útil

.

Aquellos que yo amo mejor

se meten de cabeza en su trabajo

sin demorar en el bajío;

y nadan ahí fuera con brazadas seguras,

casi fuera de la vista.

Parecen ser nativos de eso elemento,

las cabezas negras lisas de focas

que rebotan como balones semi-sumergidos.

.

Me gustan los que se enjaezan: bueyes a una carreta pesada;

búfalos de agua que jalan con un temple masivo,

que tensan en el barro y la ciénaga para avanzar las cosas;

quienes que hacen lo que debe hacer, una y otra vez.

.

Quiero estar con la gente que se sumergir en la tarea;

que va en los sembríos para cosechar;

que trabaja en línea y que difunde los costales;

hombres y mujeres que no son generales del salón y desertores del deber

sino mueven en un ritmo común

cuando tiene que traer el alimento o necesita apagar el fuego.

.

La tarea del mundo es algo común, generalizado, como el barro.

Si hacemos una chapuza, embadurna las manos y se desmigaja al polvo.

Pero la cosa bien hecha

tiene la forma que complace, algo limpio, sencillo, evidente.

Ánforas griegos por el vino o el aceite,

y jarrones por el maíz del pueblo hopi,

están colocados en museos

– pero sabes que eran cosas hechas para utilizar.

El jarro llora por el agua a llevar

y la persona por el trabajo que es auténtico.

. . .

Del poemario Circles on the Water © 1982 / Traducción del inglés: Alexander Best

. . .

Marge Piercy (born 1936, American poet, novelist, social activist)

To be of use

.

The people I love the best

jump into work head first

without dallying in the shallows

and swim off with sure strokes almost out of sight.

They seem to become natives of that element,

the black sleek heads of seals

bouncing like half-submerged balls.

.

I love people who harness themselves, an ox to a heavy cart,

who pull like water buffalo, with massive patience,

who strain in the mud and the muck to move things forward,

who do what has to be done, again and again.

.

I want to be with people who submerge

in the task, who go into the fields to harvest

and work in a row and pass the bags along,

who are not parlour generals and field deserters

but move in a common rhythm

when the food must come in or the fire be put out.

.

The work of the world is common as mud.

Botched, it smears the hands, crumbles to dust.

But the thing worth doing well done

has a shape that satisfies, clean and evident.

Greek amphoras for wine or oil,

Hopi vases that held corn, are put in museums

but you know they were made to be used.

The pitcher cries for water to carry

and a person for work that is real.

. . .

Marge Piercy

Para las mujeres fuertes

.

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer esforzada.

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer que se sostiene de puntillas

y levanta unas pesas mientras intenta cantar Boris Godunov…

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer “manos a la obra”

limpiando el pozo negro de la historia.

Y mientras saca la porquería con la pala

habla de que no le importa llorar,

porque abre los conductos de los ojos…

Ni vomitar, porque estimula los músculos del estómago…

Y sigue dando paladas, con lágrimas en la nariz.

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer con una voz en la cabeza,

que le repite: “Te lo dije: sos fea, sos mala, sos tonta…

nadie más te va a querer nunca”.

“¿Por qué no eres femenina,

por qué no eres suave y discreta…

por qué no estás muerta…?“

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer empeñada

en hacer algo que los demás están empeñados en que no se haga.

Está empujando la tapa de plomo de un ataúd desde adentro.

Está intentando levantar con la cabeza la tapa de una alcantarilla.

Está intentando romper una pared de acero a cabezazos…

Le duele la cabeza.

La gente que espera a que haga el agujero,

le dice:”date prisa…¡eres tan fuerte…!”

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer que sangra por dentro.

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer que se hace a sí misma.

Fuerte cada mañana mientras se le sueltan los dientes

y la espalda la destroza.

“Cada niño, un diente…”, solían decir antes.

Y ahora “por cada batalla… una cicatriz”.

Una mujer fuerte es una masa de cicatrices

que duelen cuando llueve.

Y de heridas que sangran cuando se las golpea.

Y de recuerdos que se levantan por la noche

y recorren la casa de un lado a otro, calzando botas…

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer que ansía el amor

como si fuera oxígeno, para no ahogarse…

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer que ama con fuerza

y llora con fuerza…

Y se aterra con fuerza y tiene necesidades fuertes…

Una mujer fuerte es fuerte en palabras, en actos,

en conexión, en sentimientos…

No es fuerte como la piedra

sino como la loba amamantando a sus cachorros.

La fuerza no está en ella,

pero la representa como el viento llena una vela.

Lo que la conforta es que los demás la amen,

tanto por su fuerza como por la debilidad de la que ésta emana,

como el relámpago de la nube.

El relámpago deslumbra, llueve, las nubes se dispersan

Sólo permanece el agua de la conexión, fluyendo con nosotras.

Fuerte es lo que nos hacemos unas a otras.

Hasta que no seamos fuertes juntas

una mujer fuerte es una mujer fuertemente asustada…

. . .

Traducción del inglés: Desconocida/o

. . .

Marge Piercy

For strong women

.

A strong woman is a woman who is straining.

A strong woman is a woman standing

on tiptoe and lifting a barbell

while trying to sing Boris Godunov.

A strong woman is a woman at work

cleaning out the cesspool of the ages,

and while she shovels, she talks about

how she doesn’t mind crying, it opens

the ducts of the eyes, and throwing up

develops the stomach muscles, and

she goes on shoveling with tears

in her nose.

.

A strong woman is a woman in whose head

a voice is repeating: I told you so,

ugly, bad girl, bitch, nag, shrill, witch,

ballbuster, nobody will ever love you back,

why aren’t you feminine, why aren’t

you soft, why aren’t you quiet, why

aren’t you dead?

.

A strong woman is a woman determined

to do something others are determined

not be done. She is pushing up on the bottom

of a lead coffin lid. She is trying to raise

a manhole cover with her head, she is trying

to butt her way through a steel wall.

Her head hurts. People waiting for the hole

to be made say: hurry, you’re so strong.

.

A strong woman is a woman bleeding

inside. A strong woman is a woman making

herself strong every morning while her teeth

loosen and her back throbs. Every baby,

a tooth, midwives used to say, and now

every battle a scar. A strong woman

is a mass of scar tissue that aches

when it rains and wounds that bleed

when you bump them and memories that get up

in the night and pace in boots to and fro.

.

A strong woman is a woman who craves love

like oxygen or she turns blue choking.

A strong woman is a woman who loves

strongly and weeps strongly and is strongly

terrified and has strong needs. A strong woman is strong

in words, in action, in connection, in feeling;

she is not strong as a stone but as a wolf

suckling her young. Strength is not in her, but she

enacts it as the wind fills a sail.

.

What comforts her is others loving

her equally for the strength and for the weakness

from which it issues, lightning from a cloud.

Lightning stuns. In rain, the clouds disperse.

Only water of connection remains,

flowing through us. Strong is what we make

each other. Until we are all strong together,

a strong woman is a woman strongly afraid.

. . .

Fehmida Riaz (Pakistani poet who writes in Urdu / born 1946, Uttar Pradesh, India)

Come, Let us create a New Lexicon

.

Come let us create a new lexicon

Wherein is inserted before each word

Its meaning that we do not like

And let us swallow like bitter potion

The truth of a reality that is not ours

The water of life bursting forth from this stone

Takes a course not determined by us alone

We who are the dying light of a derelict garden

We who are filled with the wounded pride of self-delusion

We who have crossed the limits of self-praise

We who lick each of our wounds incessantly

We who spread the poisoned chalice all around

Carrying only hate for the other

On our dry lips only words of disdain for the other

We do not fill the abyss within ourselves

We do not see that which is true before our own eyes

We have not redeemed ourselves yesterday or today

For the sickness is so dear that we do not seek to be cured

But why should the many-hued new horizon

Remain to us distant and unattainable?

So why not make a new lexicon

If we emerge from this bleak abyss?

Only the first few footsteps are hard

The limitless expanses beckon us

To the dawning of a new day

We will breathe in the fresh air

Of the abundant valley that surrounds us

We will cleanse the grime of self-loathing from our faces.

To rise and fall is the game time plays

But the image reflected in the mirror of time

Includes our glory and our accomplishments

So let us raise our sight to friendship

And thus glimpse the beauty in every face

Of every visitor to this flower-filled garden

We will encounter ‘potentials’

A word in which you and me are equal

Before which we and they are the same

So come let us create a new lexicon!

. . .

Fehmida Riaz (Poetisa paquistaní, nac. 1946, Uttar Pradesh, India)

¡Ven, creemos un nuevo léxico!

.

¡Ven, creemos un nuevo léxico!

Uno donde el sentido de cada palabra

(que no nos gusta)

está insertado antes.

Y traguemos, como un veneno amargo,

la verdad de una realidad que no es nuestra.

El agua de vida que estalla de esta piedra

conduce un rumbo que nosotros solos no determinamos.

Nosotros – que son la luz murienda de un jardín decrépito;

nosotros – llenos del orgullo herido de nuestras ilusiones;

nosotros – que han superado los límites del autobombo;

nosotros – que lamen cada herida nuestra sin cesar;

nosotros – que hacen circular el cáliz envenenado,

nosotros – que llevan del uno al otro solo el odio,

y, sobre nuestras labias secas, nada más que palabras del desdén.

No llenamos el abismo en el interior;

no vemos con nuestros propios ojos lo que es auténtico en frente de nosotros;

no nos hemos redimido ayer o hoy;

porque nuestra enfermedad es tan preciada que no buscamos un tratamiento.

¿Pero por qué el horizonte de muchos tonos debe permanecernos como

remoto y inalcanzable?

.

Entonces, ¿Por qué no creamos un nuevo léxico?

Si resurgimos de este abismo austero,

solamente las primeras pisadas serán duras.

Las extensiones ilimitadas nos atraen al amanecer de un nuevo día.

Inhalaremos el aire fresco

del valle abundante que nos rodea.

Purificaremos de nuestras caras la mugre de aversión de uno mismo.

El vaivén, el auge y caída – son estos el juego que juega el Tiempo.

Pero la imagen que vemos en el espejo del Tiempo

incluye nuestra gloria también nuestros logros

– pues alcemos la mirada hasta la amistad,

por lo tanto entrever la belleza en cada rostro

de cada visitante en este jardín de muchas flores.

Nos encontraremos con ‘potenciales’,

una palabra en que tú y yo son equitativos;

una palabra en que nosotros y ellos son iguales.

Entonces,

¡Ven, creemos un nuevo léxico!

. . .

Traducción del inglés: Alexander Best

. . .

Fehmida Riaz

Chador and Char-Diwari

.

Sire! What use is this black chador to me?

A thousand mercies, why do you reward me with this?

.

I am not in mourning that I should wear this

To flag my grief to the world

I am not a disease that needs to be drowned in secret darkness

.

I am not a sinner nor a criminal

That I should stamp my forehead with its darkness

If you will not consider me too impudent

If you promise that you will spare my life

I beg to submit in all humility,

O Master of men!

In your highness’ fragrant chambers

lies a dead body—

Who knows how long it has been rotting?

It seeks pity from you

.

Sire, do be so kind

Do not give me this black chador—

With this black chador cover the shroudless body

lying in your chamber

.

For the stench that emanates from this body

Walks buffed and breathless in every alleyway

Bangs her head on every doorframe

Covering her nakedness

.

Listen to her heart-rending screams

Which raise strange spectres

That remain naked in spite of their chador.

Who are they ? You must know them, Sire.

.

Your highness must recognize them

These are the hand-maidens,

The hostages who are halal for the night.

With the breath of morning they become homeless

They are the slaves who are above

The half-share of inheritance for your

Highness’s off-spring.

.

These are the Bibis

Who wait to fulfill their vows of marriage

In turn, as they stand, row upon row

They are the maidens

On whose heads, when your highness laid a hand

of paternal affection,

The blood of their innocent youth stained the

whiteness of your beard with red.

In your fragrant chamber, tears of blood

life itself has shed

Where this carcass has lain

For long centuries, this body—

spectacle of the murder

of humanity.

.

Bring this show to an end now.

Sire, cover it up now—

Not I, but you need this chador now.

.

For my person is not merely a symbol of your lust:

Across the highways of life, sparkles my intelligence;

If a bead of sweat sparkles on the earth’s brow it is

my diligence.

.

These four walls, this chador I wish upon the

rotting carcass.

In the open air, her sails flapping, races ahead

my ship.

I am the companion of the New Adam

Who has earned my self-assured love.

. . .

Translation form Urdu: Rukhsana Ahmed

. . .

Halima Xudoyberdiyeva (born 1947, Boyovut, Uzbekistan)

Sacred Woman

(Translation from Uzbek: Johanna-Hypatia Cybeleia)

.

Your lovers have thrown flowers at your feet,

In solitude they have tasted honey from your lips,

And they have sold it to anyone at all,

You are sacred anyway, sacred woman.

.

First they came to fill your embrace, and told you to shine

You did not consent, woman, though people said the opposite

Unable to reach you, they turned their faces and called you bitter

You are sacred anyway, sacred woman.

.

You flutter your wings slowly and you lay your head down,

It’s been thousands of years, your eyes sparkle with tears,

A thousand and one criminals will hurt you with stones,

You are sacred anyway, sacred woman.

.

Though you come silently when summoned, though you come uselessly,

Though you come humbly to the drunken circle, though you come pleading to scoundrels,

Though you come oppressed to the scoundrels, though you come humbly,

You are sacred anyway, sacred woman.

.

In fact you’ll have amusements where you go,

Good and bad stories where you go,

You’ll have men like wild horses where you go,

You are sacred anyway, sacred woman.

.

Your silk-perfume body has the marks of stones,

Your bosom has the traces of heads that have leaned there,

You have the remnants of suns whose sun-fire has burned out,

You are sacred anyway, sacred woman.

. . .

Halima Xudoyberdiyeva

Water Flowing in Front of Me

.

To live in ease, to live in torment,

Not uselessly inclined away from you another sky,

My lifetime of hunting for hearts is over with,

There’s not even any thought of you going away.

.

Water flowing in front of me, my unappreciated water,

Enjoying myself for once in my life, I don’t feel relieved.

Ongoing sympathy, my secret water;

Until it dried up, I was not noticed.

.

I tell others don’t go away from me,

I go to find them in the dawn and evening time;

I offend others, telling them don’t show up;

I don’t even think anything about your going away.

.

I ran to others in cities, in towns,

You didn’t turn back or get sarcastic once.

Here I am, I’m the prey; here I am, I’ll go away,

Saying why didn’t you remind me once?

My mother, O my mother?!

. . .

Water Flowing in Front of Me in the original Uzbek:

.

Oldimdan Oqqan Suv

.

Yashamoq farog’at, yashamoq azob,

Bekorga egilmas Sizdan boshqa ko’k,

Ko’ngillarni ovlab umrim bo’pti sob,

Sizning ketishingiz xayolda ham yo’q.

.

Oldimdan oqqan suv, beqadr suvim,

Umrida bir yayrab, yozilmaganim.

Bor turishi shafqat, bori sir suvim,

To qurib qolguncha sezilmaganim.

.

Boshqalar yonimdan ketmasin debman,

Vaqt topib ularga boribman tong-kech,

Boshqalarga ozor yetmasin debman,

Sizga ham yetishin o’ylamabman hech.

.

Boshqalarga chopdim shahar, kentda man,

Bir qaytarib yo bir kesatmadingiz,

Manam g’animatman, manam ketaman,

Deb nechun bir bora eslatmadingiz?

Onam, onam-a?!

. . . . .

“A la Vida” / “Here’s to Life”: canción distintiva de Shirley Horn

Posted: February 29, 2016 Filed under: English, Spanish, Translator's Whimsy: Song Lyrics / Extravagancia del traductor: Letras de canciones traducidas por Alexander Best Comments Off on “A la Vida” / “Here’s to Life”: canción distintiva de Shirley HornA la Vida (letras: Phyllis Molinary / música: Artie Butler)

[canción distintiva de Shirley Horn (1934-2005)]

.

No tengo quejas ni arrepentimientos.

Aún creo en perseguir los sueños y hacer las apuestas.

Pero yo he aprendido ésto:

lo que tú das es todo que recibirás

– entonces dála una mejor vuelta en esta vida.

.

He tenido mi porción y he bebido más que bastante.

Y aunque estoy satisfecha, aún así tengo hambre de

ver lo que hay más adelante, más allá de la cresta de la colina

y hacerlo todo – de nuevo.

.

Pues, ¡a la Vida! y a todo el júbilo que nos jala.

Pues, ¡a la Vida! –– por los visionarios y sus sueños.

.

Raro es como vuela el Tiempo,

como el amor cambiará de hola acogedora hacia adiós triste;

como el amor te deja con los recuerdos que ya has memorizado

– para mantenerte caliente durante esos inviernos.

.

Mira, no hay “sí” en “ayer”,

¿Y quién comprende lo que lleve la mañana

– o lo que la mañana requise?

Pero siempre y cuando yo sea parte del juego pues quiero jugarlo

– por las risas, por la vida, y por el amor.

.

Entonces…¡a la Vida! y a todo el gozo que nos jala.

Sí, ¡a la Vida! –– por los soñadores y sus visiones.

Que soportares las tormentas, y

que mejorare todo lo que ya es bueno.

A la Vida… al Amor…

y…¡a ti!

. . .

Here’s to Life (lyrics by Phyllis Molinary / music by Artie Butler)

[as sung by Shirley Horn (1934-2005)]

.

No complaints and no regrets,

I still believe in chasing dreams and placing bets.

But I have learned that all you give is all you get;

So give it all you got.

.

I had my share, I drank my fill; and even though

I’m satisfied––I’m hungry still

To see what’s down another road, beyond the hill––

And do it all again.

.

So here’s to Life and all the joy it brings.

Here’s to Life––for dreamers and their dreams.

.

Funny how the time just flies,

How love can go from warm hellos to sad goodbyes,

And leave you with the memories you’ve memorized

To keep your winters warm.

For there’s no ‘yes’ in yesterday; and who knows what tomorrow brings or takes away? As long as I’m still in the game I want to play

For laughs, for life, for love.

.

So here’s to Life and every joy it brings.

Here’s to Life––for dreamers and their dreams.

.

May all your storms be weathered,

And may all that’s good get better.

Here’s to life, here’s to love, here’s to you.

.

May all your storms be weathered,

And may all that’s good get better.

Here’s to life, here’s to love, here’s to you!

. . .

Interpretación por Shirley Horn:

https://youtu.be/UTv3TONfTTQ

. . . . .

Audre Lorde: poemas traducidos (1962-1973)

Posted: February 18, 2016 Filed under: A FEW FAVOURITES / UNA MUESTRA DE FAVORITOS, Audre Lorde, Audre Lorde: poemas traducidos, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: El Mes de la Historia Afroamericana: Poetas Comments Off on Audre Lorde: poemas traducidos (1962-1973)

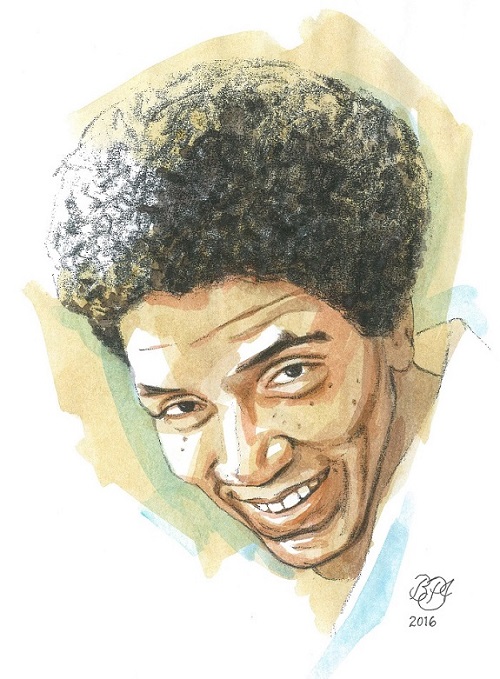

Retrato de Audre Lorde por Bruce Patrick Jones_grafito y acuarela_2016 / Portrait of Audre Lorde by Bruce Patrick Jones_graphite and watercolour_2016