Robert Gurney: “Horneritos” / “Ovenbirds”

Posted: July 31, 2013 Filed under: English, Robert Gurney, Spanish Comments Off on Robert Gurney: “Horneritos” / “Ovenbirds” ZP_Crested Hornero in Argentina_Furnarius cristatus en Argentina_foto por Nick Athanas

ZP_Crested Hornero in Argentina_Furnarius cristatus en Argentina_foto por Nick Athanas

.

Robert Gurney

“Horneritos”

( a Ramón Minieri )

.

Recibí un mail desde la Patagonia

acerca de unos pájaros.

.

Tienen el plumaje de la cabeza

estilo punk.

.

Dicen que son oriundos

del Paraguay y del Chaco

pero que a veces vuelan

hasta la Pampa

y otras incluso

hasta la Patagonia.

.

El mail describe

cómo descienden a comer

en el patio de un amigo

que vive en Río Colorado.

.

Luego vuelven a un árbol

para posar ante la cámara.

.

Ni siquiera se molestan

en peinarse primero.

.

Otro amigo,

que vive en Londres,

me dice que se llaman

horneritos copetones

y que sus nidos se parecen

a los hornos de los panaderos.

.

Pero no es eso

lo que me llama la atención

sino la imagen

del horno de barro

en la pared

de la casa de Vallejo*

en Santiago de Chuco.

.

Hay pájaros

que van y vienen,

entrando y saliendo

de su boca.

.

* César Vallejo, poeta peruano, 1892 – 1938

. . .

Robert Gurney

“Ovenbirds”

( to Ramón Minieri )

.

I had an e-mail the other day

from Patagonia

about some birds

with punk-style head feathers.

.

It said they are native

to Paraguay

and The Chaco

but that they sometimes

fly south

to the Pampas

and, sometimes,

even, to Patagonia.

.

It describes how

they come down to feed

in a friend’s patio

in Río Colorado.

.

Then they fly back into a tree

to pose for the camera

without even bothering

to comb their hair first.

.

Another friend,

who lives in London,

tells me that they are called

“horneritos copetones”

(furnarius cristatus);

in English –

Crested Horneros

or Ovenbirds;

and that they nest

in shrubs in scrub.

.

It seems

that they are so named

because they make

globular mud nests

that resemble

bakers’ ovens.

.

It wasn’t so much this,

though,

that filled my mind

but an image

of an oven in a wall

inside Vallejo’s* house

in Santiago de Chuco

with birds flying

in and out of it.

.

(St. Albans, England, June 2013)

.

* César Vallejo, Peruvian poet, 1892 – 1938

. . .

Robert Gurney nació en Luton, Bedfordshire, Inglaterra. Divide su tiempo ahora entre St Albans, Hertfordshire, Inglaterra, y la aldea de Port Eynon en El País de Gales. Su esposa Paddy es galesa. Tienen dos hijos y dos nietos. Su primer profesor de Español en el liceo de Luton, el señor Enyr Jones, era argentino, precisamente patagónico galés, de Gaiman. Las clases eran una oasis de paz, amistad e inspiración: un grupo pequeño en la biblioteca, sentado en un círculo alrededor de una elegante mesa de madera, con los diccionarios a la mano. En la Universidad de St Andrew’s (Escocia) su profesor fue el Profesor L. J. (“Ferdy”) Woodward, quien daba maravillosas clases sobre la poesía española. Luego, en el ciclo de doctorado, en Birkbeck College, Universidad de Londres, tenía al profesor Ian Gibson como mentor inspiracional. Con la supervisión de Ian preparó su tesis doctoral sobre Juan Larrea (The Poetry of Juan Larrea, 1975), poeta al que entrevistó en francés en treinta y seis oportunidades (200 horas) en 1972, en Córdoba, Argentina. La Universidad del País Vasco publicó La poesía de Juan Larrea en 1985. Mantuvo una correspondencia intensa con el poeta (inédita). Entrevistó a Salvador Dalí, a Gerardo Diego, a Luis Vivanco (el traductor de Larrea), a José María de Cossío y a los amigos de Larrea en España y Argentina: Gregorio San Juan, Osvaldo Villar, Luis Waysmann y otros. Escribe poesía y cuentos. Ha escrito una novela ‘anglo-argentina’ (inédita). Su último poemario La libélula / The Dragonfly (edición bilingüe) salió este año en Madrid. Su próximo libro, también bilingüe, será La Casa de empeño / The Pawn Shop (Ediciones Lord Byron). Prepara un libro de cuentos breves sobre sus años en Buganda.

Para leer más poemas de Robert Gurney cliquea aquí: http://verpress.com/

.

Robert Gurney was born in Luton, Befordshire, England. He divides his time now between St Albans, Hertfordshire and the village of Port Eynon in Wales. His wife Paddy is Welsh. They have two sons and two grandsons. His first Spanish teacher at Luton Grammar School, Mr Enyr Jones, was Argentine, Patagonian Welsh, to be precise, from Gaiman. The classes were an oasis of peace, friendship and inspiration: a small group sitting in a circle around an elegant wooden table in the library, with dictionaries to hand. At the University of St Andrew’s in Scotland, his teacher was Professor L.J. (“Ferdy”) Woodward who gave marvelous lectures on Spanish poetry. Then, for his PhD at Birkbeck College, the University of London, he had Ian Gibson as his inspirational tutor. Under Ian’s supervision, he wrote his thesis on Juan Larrea (The Poetry of Juan Larrea, 1975), published by the University of the Basque Country as La poesía de Juan Larrea in 1985. He interviewed Larrea, in French, on 36 separate occasions in Córdoba, Argentina, in 1972, and conducted an intense correspondence with him. He interviewed Salvador Dalí, Gerardo Diego (in Spain and France), Luis Vivanco (Larrea’s translator), Jose María de Cossío and Larrea’s friends in Argentina: Ovaldo Villar, Luis Waysmann and others. He has written one “Anglo-Argentine” novel (unpublished). He writes poetry and short stories and is currently preparing a book of short stories on his years in Buganda.

. . . . .

Alan Clark: “La Lengua” y “Dentro de Ti”

Posted: July 31, 2013 Filed under: Alan Clark, English, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Alan Clark: “La Lengua” y “Dentro de Ti” ZP_La Lengua_pintura de Alan Clark

ZP_La Lengua_pintura de Alan Clark

.

La Lengua

.

Estoy “viviendo” tu leyenda sobre mi lengua

(es ésta la tierra santa en que vagaremos…)

Contigo…degustas como las palabras que me vienen,

esta lengua rastreando tus “dondes” más dulces,

y estas palabras hacen cosquillas en la garganta.

Pero está en tu piel que conozco lo que es

la adoración – la lengua, con franqueza, sobre

la piel de sal / sobre brazas de ti

(no bajo del agua sino en un nuevo aire de sal)

en que el universo – que es tú – ríe un “yo” para

bajarme más y más y inventir todas las palabras

que nunca te igualarán – la ola y “materia”

del cuento en el lenguaje de nuestro sueño

unido en nosotros…

Somos diosas y dioses del sudor,

del pecho, de las manos, y de los labios que

hablan solamente cuando no hay nada decir que:

Quede en en lugar oscuro donde están conocidos

tus muslos en lo de mi que está bastante liviano

para buscarte.

. . .

La Lengua

.

I’m living out your legend on my tongue

(this is the holy land we’re wandering in)

with you tasting like the words that come to me,

this tongue tracking down your softest “wheres”,

these words tickling my throat. But in your flesh

I know what worship is, tongue directly

to the salt skin and fathoms of yourself

(not under water, in a new salt air)

in which the universe of you is laughing me

to go down and down to make up all the words

that will never equal you, wave and matter

as the story in the language of our dream

together: goddesses and gods of sweat,

of breasts and hands and lips that only speak

when there’s nothing left to say but: Linger,

in the dark place where your thighs are met

by what of me is light enough to find you.

. . .

Dentro de Ti –

.

Puedo ver la materia prima de sombras

y como el barro se torne en una clase de luz;

que soy como un pez que debe nadar

dentro de un mundo donde se arremolinan la hierba del mar

mientras levantas las manos durante un día caluroso…

Me siento dentro de ti la verde pura de una planta que

se torna en el calor de un horno de sangre;

lo que está ni despierto ni durmiendo en

la concha de un otro día que promete

todo de sí mismo para expectativas no perladas…

El olor en tu animal, la flor de mi lengua de pavo real;

el diccionario de mis sentidos no deletreados como besos; y

siempre – siempre – la libertad del cielo

recogiendo las plumas de un pájaro – tú – que

se monta los alientos cuando miran tus ojos que

pueden asegurar – por la ley rarísima – algo que

nunca viere alguien:

las balanzas de los arcos de iris breves

y la creación del mundo.

. . .

In You –

.

I can see what stuff shadows are made of

and how clay can become a kind of light,

how I’m like a fish who can’t not swim

into a world where the seagrass is swirling

when you lift up your arms on a hot day…

feel in you the raw green of a plant

being turned into heat in an oven of blood,

what lies not awake, not asleep inside

the shell of another day promising

all of itself to no pearl expectations…

smell in your animal, the flower

of my peacock tongue, the dictionary

of my senses unspelled as kisses, and

always, always, the freedom of the sky

gathering the feathers of the bird you are,

who rides the winds when your eyes behold,

who can claim by the strangest of laws

what no-one else could ever see: the scales

of brief rainbows and the world’s creation.

. . .

Poeta y pintor, Señor Alan Clark divide su vida entre Maine en EE.UU. y el México. Guerrero y Sangre del Corazón fue publicado por Henning Bartsch (México, D.F.) Tiene también un poemario de 2010: Where They Know. Sus piezas del teatro incluyen: The End of It, The Couch – The Table – The Bed, and The Beast – y fueron montados en EE.UU. y México. En 2004 tuvo una exhibición de sus pinturas en Rockland, Maine en Farnsworth Art Museum – Sangre y Piedra.

.

Alan Clark is an artist and poet, dividing his life between Maine and Mexico. Guerrero and Heart’s Blood was published in Mexico City by Henning Bartsch. A book of poems, Where They Know, was published in 2010. Clark’s plays –including adaptations of Guerrero and Heart’s Blood – include: The End of It, The Couch – The Table – The Bed, and The Beast; these have been staged in the U.S.A. and in Mexico. Blood and Stone: Paintings by Alan Clark,was at the Farnsworth Art Museum, Rockland, Maine,in 2004.

Versiones en español / Spanish versions: Alexander Best

. . . . .

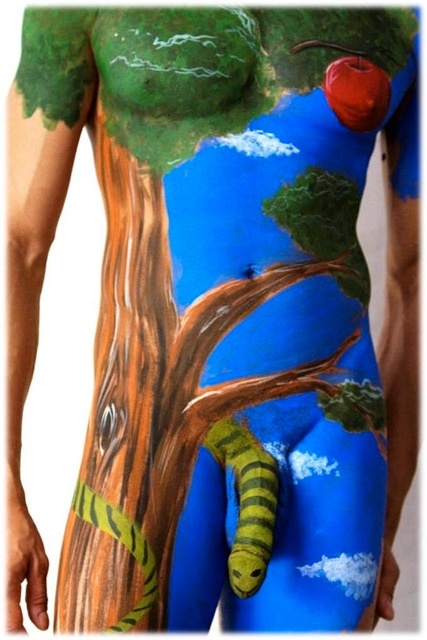

¿Eva, La Culpable? / Was IT All Eve’s Fault?

Posted: July 28, 2013 Filed under: English, Eva La Culpable...Was It All Eve's Fault?, Jee Leong Koh, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on ¿Eva, La Culpable? / Was IT All Eve’s Fault? ZP_El Adán reconsiderado…¡Piense en él dos veces!_Adam reconsidered…Give him a second thought!

ZP_El Adán reconsiderado…¡Piense en él dos veces!_Adam reconsidered…Give him a second thought!

.

“No Eva…Solo era una cantidad excesiva del Amor, su Culpa.”

(Aemilia Lanyer, poetisa inglés, 1569 – 1645, en su obra Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum: La Apología de Eva por La Mujer, 1611)

.

Jee Leong Koh

“Eva, La Culpable”

.

Aunque se ha ido del jardín, no se para de amarles…

Dios le convenció cuando sacó rápidamente de su manga planetaría

un ramo de luz. Miraron pasar el desfile de animales.

Le contó el chiste sobre el Arqueópterix, y se dio cuenta de

las plumas y las garras brutales – un poema – el primero de su tipo.

En una playa, alzado del océano con un grito, él entró en ella;

y ella, en olas onduladas, notó que el amor une y separa.

.

El serpiente fue un tipo más callado. Llegaba durante el otoño al caer la tarde,

viniendo a través de la hierba alta, y apenas sus pasos dividió las briznas.

Cada vez él le mostró una vereda diferente. Mientras que vagaban,

hablaron de la belleza de la luz golpeando en el árbol abedul;

el comportamiento raro de las hormigas; la manera más justa de

partir en dos una manzana.

Cuando apareció Adán, el serpiente se rindió a la felicidad la mujer Eva.

.

…Porque ella era feliz cuando encontró a Adán bajo del árbol de la Vida

– y aún está feliz – y Adán permanece como Adán: inarticulado, hombre de mala ortografía;

su cuerpo estando centrado precariamente en sus pies; firme en su mente que

Eva es la mujer pristina y que él es el hombre original. Necesitó a ella

y por eso rasguñó en el suelo – y creyó en el cuento de la costilla.

Eva necesitó a la necesidad de Adán – algo tan diferente de Dios y el Serpiente,

Y después de éso ella se encontró a sí misma afuera del jardín.

. . .

“Not Eve, whose Fault was only too much Love.”

(Aemilia Lanyer, English poetess, 1569 – 1645, in Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum: Eve’s Apologie in Defence of Women, 1611)

.

Jee Leong Koh

“Eve’s Fault”

.

Though she has left the garden, she does not stop loving them.

God won her when he whipped out from his planetary sleeve

a bouquet of light. They watched the parade of animals pass.

He told her the joke about the Archaeopteryx, and she noted

the feathers and the killing claws, a poem, the first of its kind.

On a beach, raised from the ocean with a shout, he entered her

and she realized, in rolling waves, that love joins and separates.

.

The snake was a quieter fellow. He came in the fall evenings

through the long grass, his steps barely parting the blades.

Each time he showed her a different path. As they wandered,

they talked about the beauty of the light striking the birch,

the odd behavior of the ants, the fairest way to split an apple.

When Adam appeared, the serpent gave her up to happiness.

.

For happy she was when she met Adam under the tree of life,

still is, and Adam is still Adam, inarticulate, a terrible speller,

his body precariously balanced on his feet, his mind made up

that she is the first woman and he the first man. He needed

her and so scratched down and believed the story of the rib.

She needed Adam’s need, so different from God and the snake

– and that was when she discovered herself outside the garden.

. . . . .

Jee Leong Koh nació en Singapur y vive en Nueva York. Es profesor, también autor de cuatro poemarios.

Jee Leong Koh was born in Singapore and now lives in New York City where he is a teacher.

He is the author of four poetry collections: Payday Loans, Equal to the Earth, Seven Studies for a Self Portrait and The Pillow Book.

. . .

Traducción en español / Translation into Spanish: Alexander Best

. . . . .

Alicia Claudia González Maveroff: “The Storyteller in The Zócalo” / “El Fabulador del Zócalo”

Posted: July 25, 2013 Filed under: Alicia Claudia González Maveroff, English, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Alicia Claudia González Maveroff: “The Storyteller in The Zócalo” / “El Fabulador del Zócalo”.

Alicia Claudia González Maveroff

“The Storyteller in The Zócalo”

.

Earlier today in the Square there was a storyteller

enchanting people with his words – everyone who

was in and around that patch of pavement where he stood.

Those who saw him there were all listening without

so much as uttering a sound.

In The Zócalo this man earns his livelihood, selling

pretty little dolls that wiggle and sway.

Even though you can’t see any strings pulled,

you don’t know how it’s done,

these little dolls –skeletons, rather –

dance, lie down, jump, kneel and walk,

while the vendor chatters like a “fairground charlatan”.

Incredible it was, the gift of the gab that fellow displayed.

He whiled away the time offering to passers-by

a cadaverous doll which seemed to be alive-and-kicking.

Children, mute, admired the dancing doll:

“Look how the dolly can dance!”

The adults present laughed to themselves, “Yeah, right,”

as if to say: “What a scam.”

Yet he captured every one of us, this guy with his confabulations,

presenting those dolls that never ceased to dance.

Who knows what the trick is? There’s no harm in it…

For that reason, in fact, one has to hand it to him this evening,

knowing that this is all a hoax yet rascal-ishly fascinating…

Me, he left me bamboozled, making me believe him,

so I’ve gone and bought one of those little dolls

– in order to be rewarded with a performance.

And I have left the Square happy, yes – knowing that he‘s a crook…

.

Mexico City, July 22nd, 2012

. . .

Alicia Claudia González Maveroff

“El Fabulador del Zócalo”

.

Estaba el fabulador en la plaza hoy temprano,

encantando con palabras,

a todos los que rodeaban el sector donde se hallaba.

Esos que allí se encontraban, lo escuchaban sin hablar.

En el Zócalo este hombre gana su vida, vendiendo

unos muñequitos lindos pequeños que se menean.

Aunque no se ven cordeles, ni sabemos como lo hace,

estos pequeños muñecos, a más decir esqueletos,

bailan, se barazan, se acuestan, saltan, se arrodillan y andan,

mientras el vendedor habla como “charlatan de feria”.

Es increible la labia que este señor nos demuestra.

Pasa su tiempo ofreciendo, a todos los transeuntes,

el muñeco cadaverico, que está vivito y coleando.

Mientras el muñeco baila, los niños, quietos, lo admiran.

¡Cómo baila el muñequito!

Los grandes, sonriendo “a penas”, como diciendo

“¡es un cuento!”

Pero a todos ha atrapado, este señor con su charla,

ofreciendo los muñecos que no paran de bailar.

¿Quién sabe como es el truco? No lo hacen nada mal…

Por eso, por la actuación, que ha brindado él esta tarde,

sabiendo que es un engaño, que es un vil fascinador…

Yo, me he dejado embaucar, haciendo que le creía,

le he comprado un muñequito, para premiar su actuación.

Y me he marchado contenta, sabiendo que es un ladrón…

.

México D.F., 22 – 07 – 2012

.

Alicia Claudia González Maveroff is a professor living in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Her credo, in a single precise sentence, is: I believe in Utopia – because Reality strikes me as impossible.

Alicia Claudia González Maveroff es una profesora que vive en Buenos Aires, Argentina. En una oración sucinta, su consejo es ésto: Creo en la utopía, porque la realidad me parece imposible.

.

Translation and interpretation from Spanish into English / Versión inglés: Alexander Best

. . . . .

Poemas japoneses – de guerra, del honor, de la ternura – traducidos por Nuna López

Posted: July 20, 2013 Filed under: Akiko Yosano, English, Japanese, Kaneko Misuzu, Sadako Kurihara, Spanish, ZP Translator: Nuna López | Tags: Poemas japoneses de guerra Comments Off on Poemas japoneses – de guerra, del honor, de la ternura – traducidos por Nuna López

ZP_Samurai writing a poem on a flowering cherry-tree trunk by Ogata Gekko, 1859-1920_ print courtesy of ogatagekkodotnet

ZP_Samurai writing a poem on a flowering cherry-tree trunk by Ogata Gekko, 1859-1920_ print courtesy of ogatagekkodotnet

.

Ouchi Yoshitaka (a “daimyo” or feudal lord / un “daimyo” o soberano feudal, 1507-1551)

.

Both the victor and the vanquished are

but drops of dew, but bolts of lightning –

thus should we view the world.

. . .

Tanto el vencedor como el vencido no son

Sino gotas de rocío, relámpagos –

así deberíamos ver el mundo.

. . .

Hojo Ujimasa (1538-1590)

Hojo was a “daimyo” and “samurai” who, after a shameful defeat, committed “seppuku” or ritual suicide by self-disembowelment. He composed a poem before he killed himself:

.

“Death Poem”

.

Autumn wind of evening,

blow away the clouds that mass

over the moon’s pure light

and the mists that cloud our mind –

do thou sweep away as well.

Now we disappear –

well, what must we think of it?

From the sky we came – now we may go back again.

That’s at least one point of view.

. . .

Hojo Ujimasa (1538-1590)

“Poema de muerte”

.

Viento otoñal de la noche,

sopla lejos las nubes que obstruyen

la luz pura de la luna

y la neblina que nubla nuestra mente-

también bárrela lejos.

Ahora nosotros desaparecemos –

Y bien, ¿qué deberíamos pensar de esto?

Del cielo vinimos- ahora debemos regresar otra vez.

Ese es al menos un punto de vista.

. . .

The following poem by Akiko Yosano was composed as if to her younger brother who was drafted to fight in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). It was never specifically anti-war only that the poet wished that her brother not sacrifice his life. At the time the poem was not censored but in the militaristic 1930s it was banned in Japan.

.

Akiko Yosano/ 与謝野晶子(1878-1942)

.

Oh, my brother, I weep for you.

Do not give your life.

Last-born among us,

You are the most beloved of our parents.

Did they make you grasp the sword

And teach you to kill?

Did they raise you to the age of twenty-four,

Telling you to kill and die?

.

Heir to our family name,

You will be master of this store,

Old and honoured, in Sakai, and therefore,

Brother, do not give your life.

For you, what does it matter

Whether Lu-Shun Fortress falls or not?

The code of merchant houses

Says nothing about this.

.

Brother, do not give your life.

His Majesty the Emperor

Goes not himself into the battle.

Could he, with such deeply noble heart,

Think it an honour for men

To spill one another’s blood

And die like beasts?

.

Oh, my brother, in that battle

Do not give your life.

Think of mother, who lost father just last autumn.

How much lonelier is her grief at home

Since you were drafted.

Even as we hear about peace in this great Imperial Reign,

Her hair turns whiter by the day.

.

And do you ever think of your young bride,

Who crouches weeping behind the shop curtains

In her gentle loveliness?

Or have you forgotten her?

The two of you were together not ten months before parting.

What must she feel in her young girl’s heart?

Who else has she to rely on in this world?

Brother, do not give your life.

. . .

Akiko Yosano/ 与謝野晶子(Poetisa japonesa, 1878-1942)

.

Oh, hermano mío, lloro por ti.

No entregues tu vida.

El más pequeño de nosotros,

El más amado por nuestros padres.

¿Ellos te hicieron empuñar la espada

y te enseñaron a matar?

¿Ellos te criaron hasta los veinticuatro

para matar y morir?

.

Heredero de nuestro nombre

Tú serás el dueño de esta tienda,

Vieja y honrada, en Sakai, y por eso,

Hermano, no entregues tu vida.

¿A ti que puede importarte

si la fortaleza Lu- Shun cae o no?

En el código de los comerciantes

No hay nada sobre esto.

.

Hermano, no entregues tu vida.

Su Majestad el Emperador

no pelea su propia batalla.

¿Puede él, con su profundamente noble corazón,

pensar que es un honor para los hombres

derramar la sangre de uno y otro

y morir como bestias?

Oh, hermano mío, en esa batalla

no entregues tu vida.

Piensa en mamá, que perdió a papá apenas el otoño pasado.

Qué tan solitaria es su pena en casa

desde que te enlistaron.

Incluso cuando escuchamos sobre paz en este gran Reino Imperial

su cabello se torna más blanco cada día.

.

¿Alguna vez piensas en tu joven novia,

que se acuclilla llorando tras las cortinas de la tienda

con su gentil afecto?

¿O la has olvidado?

Ustedes estuvieron juntos no más de diez meses antes de separarse.

¿Cómo debe sentirse ella en su joven corazón de niña?

¿En quién más puede confiar en este mundo?

Hemano, no entregues tu vida.

. . .

Kaneko Misuzu (Japanese poetess, 1903-1930)

“To Love Everything”

.

I wish I could love them,

Anything and everything.

.

Onions, tomatoes, fish,

I wish I could love them all.

.

Side dishes, and everything.

Because Mother made them.

.

I wish I could love them,

Anyone and everyone.

.

Doctors, and crows,

I wish I could love them all.

.

Everyone in the whole world

– Because God made them.

. . .

Kaneko Misuzu (Poetisa japonesa, 1903-1930)

“Amar todo”

.

Desearía poder amarlos,

a cualquier cosa y a todo.

Cebollas, tomates y pescados,

desearía poder amarlos todos.

Guarniciones y todo,

porque Mamá los hizo.

Desearía poder amarlos,

a cualquiera y a todos.

Doctores y cuervos,

desearía poder amarlos todos.

Todos en todo el mundo

– Porque Dios los hizo.

. . .

Kaneko Misuzu

“Me, the little bird, and the bell”

.

私が両手をひろげても、(watashi ga ryōte wo hirogete mo)

お空はちっとも飛べないが、(osora wa chitto mo tobenai ga)

飛べる小鳥は私のように、(toberu kotori ha watashi yō ni)

地面を速く走れない。(jimen wo hayaku hashirenai)

.

私が体をゆすっても、(watashi ga karada wo yusutte mo)

きれいな音はでないけど、(kirei na oto wa denai kedo)

あの鳴る鈴は私のように、(anonaru suzu wa watashi no yō ni)

たくさんな唄は知らないよ。(takusan na uta wa shiranai yo)

.

鈴と、小鳥と、それから私、(suzu to kotori to sorekara watashi)

みんなちがって、みんないい。(minna chigatte, minna ii)

. . .

Even if I stretch out my arms

I can’t fly up into the sky,

But the little bird who can fly

Cannot run fast along the ground like me.

.

Even if I shake my body,

No beautiful sound comes out,

But the ringing bell does not

Know many songs like me.

.

The bell, the little bird and, finally, me:

We’re all different, but we’re all good.

. . .

Kaneko Misuzu

“El pajarito, la campanilla y yo”

.

Aunque estire mis brazos

No puedo elevarme hacia el cielo

Pero el pajarito que puede volar

No puede correr rápido sobre la tierra, como yo.

.

Aunque sacuda mi cuerpo

Ningún bello sonido se escuchará

Pero la campanilla no conoce

Tantas canciones como yo.

.

La campanilla, el pajarito y finalmente, yo:

Todos somos diferentes pero todos igualmente buenos.

. . .

Kenzo Ishijima(Japanese Kamikaze pilot, WW2 / Piloto japonés kamikaze, Segunda Guerra Mundial)

.

Since my body is a shell

I am going to take it off

and put on a glory that will never wear out.

. . .

Ya que mi cuerpo es una carcasa

Voy a quitármela de encima

Y a vestirme de gloria que nunca se desgastará.

. . .

“Doki no Sakura”: a popular soldiers’ song of the Japanese Imperial Navy during WW2 in which a Kamikaze naval aviator addresses his fellow pilot – parted in death:

.

“Doki no Sakura”(“Cherry blossoms from the same season”)

.

You and I, blossoms of the same cherry tree

That bloomed in the naval academy’s garden.

Blossoms know they must blow in the wind someday,

Blossoms in the wind, fallen for their country.

.

You and I, blossoms of the same cherry tree

That blossomed in the flight school garden.

I wanted us to fall together, just as we had sworn to do.

Oh, why did you have to die, and fall before me?

.

You and I, blossoms of the same cherry tree,

Though we fall far away from one another.

We will bloom again together in Yasukuni Shrine.

Spring will find us again – blossoms of the same cherry tree.

. . .

“Doki no Sakura”: una canción popular entre los soldados japoneses de la Segunda Guerra Mundial:

.

“Flores de cerezo de la misma estación”

.

Tú y yo, flores de un mismo cerezo

que floreció en el jardín de la academia naval.

Flores sabedoras de que deben volar en el viento algún día,

flores en el viento, caídas por su país.

.

Tú y yo, flores de un mismo cerezo

que floreció en el jardín de la escuela de aviación.

Quería que cayéramos juntos, como habíamos jurado hacer.

Oh, ¿por qué tenías que morir y caer antes que yo?

.

Tú y yo, flores de un mismo cerezo,

aunque caemos lejos el uno del otro,

floreceremos juntos otra vez en el santuario Yasukuni.

La primavera nos encontrará otra vez – flores de un mismo cerezo.

ZP_Cherry Blossom and Crow by Ogata Gekko, 1859 – 1920_print courtesy of ogatagekkodotnet

ZP_Cherry Blossom and Crow by Ogata Gekko, 1859 – 1920_print courtesy of ogatagekkodotnet

.

Sadako Kurihara (Japanese poetess, 1913-2005)

“ When we say ‘Hiroshima’ ”

.

When we say Hiroshima, do people answer,

gently, Ah, Hiroshima? …Say Hiroshima,

and hear Pearl Harbor. Say Hiroshima,

and hear Rape of Nanjing. Say Hiroshima,

and hear women and children in Manila, thrown

into trenches, doused with gasoline, and

burned alive. Say Hiroshima, and hear

echoes of blood and fire. Ah, Hiroshima,

we first must wash the blood off our own hands.

. . .

Sadako Kurihara (Poetisa japonesa, 1913-2005)

“Cuando decimos ‘Hiroshima’”

.

Cuando decimos Hiroshima, acaso la gente contesta,

gentilmente, Ah Hiroshima?… Di Hiroshima,

y escucha Pearl Harbor. Di Hiroshima,

y escucha la Violación de Nanjing. Di Hiroshima

y escucha a las mujeres y los niños en Manila, arrojados

en zanjas, empapados en gasolina y

quemados vivos. Di Hiroshima, y escucha

ecos de sangre y fuego. Ah, Hiroshima,

primero debemos lavarnos la sangre de nuestras propias manos.

. . .

Traducciones del inglés al español / Translations from English to Spanish: Nuna López

. . . . .

“Los Tres Arbolitos” de Clovis S. Palmer y “Árboles” de Joyce Kilmer

Posted: July 11, 2013 Filed under: Clovis S. Palmer, English, Joyce Kilmer, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on “Los Tres Arbolitos” de Clovis S. Palmer y “Árboles” de Joyce KilmerClovis S. Palmer

“Los Tres Arbolitos”

.

Es redondo el mundo que nadie no ve,

y hay árboles de todas necesidades.

Algunos puedan ser grandes – otros, pequeños

– o, quizás, como muñequitos.

Puedan variar los árboles, tamaño por tamaño,

Están vistos por todas partes – y entre diques también.

Y nadie sabe de donde vienen.

.

Recordó mi mente unos tres arbolitos

– sobre una colina – a las tres y cuarto

– sí, sobre una colina y junto al molino

– tres arbolitos con miembros oleandos.

Estaban allá – cansados, hambrientos

– y esperaban por un jarrito de cerveza.

Sin embargo, se quedaron dormidos,

con sus manos colgantes

– directo allí.

. . .

Señor Palmer hoy es médico y escribió este poema cuando era niño de trece años (en 1987). En ese tiempo vivía en su pueblito natal de Manchioneal, Distrito de Portland, Jamaïca. Muestra el poema el “surrealismo natural” de la mente de la niñez. . . .Clovis S. Palmer

“Three Little Trees”

.

The world is round, which no one sees,

Having trees of all different needs.

Some may be big, some may be small – or even like a little doll.

Trees may vary from size to size,

Trees are seen from miles to miles.

Trees are seen from dam to dam and no one knows where they came from.

.

My mind went back on three little trees

Upon a hill – a quarter past three –

Upon the hill beside a mill, three little trees waving their limbs,

Hungry and tired the trees were there,

Waiting for a cup of beer.

Nevertheless, they fell asleep,

Having their hands hanging right there.

. . .

This poem was composed in 1987, in Manchioneal, Portland Parish, Jamaica, when Dr. Palmer was 13 years old. It displays the qualities of “natural surrealism” that only a child’s mind can create, whereas adults must strive greatly to see the world in such a way.Joyce Kilmer (1886-1918)

“Árboles”

.

Creo que nunca veré

un poema tan hermoso como un árbol.

Un árbol cuya boca hambrienta esté pegada

al dulce seno fluyente de la tierra;

un árbol que mira a Dios todo el día.

Y alza sus brazos frondosos para rezar.

.

Un árbol que en verano podría llevar

un nido de petirrojos en sus cabellos;

en cuyo pecho se ha recostado la nieve;

quien vive íntimamente con la lluvia.

.

Los poemas están hechos por bufones como nosotros,

Pero solo Dios puede hacer un árbol.

. . .

Escrito en 1913, el poema “Árboles” es verso bien amado entre los hablantes del inglés americano y canadiense. Claro, es muy sentimental – faltando los sellos distintos del modernismo – pero dura su estima popular porque las palabras son sinceras – de lo más hondo del corazón. . . .Joyce Kilmer (1886-1918)

“Trees”

.

I think that I shall never see

A poem as lovely as a tree;

A tree whose hungry mouth is prest

Against the earth’s sweet flowing breast;

A tree that looks at God all day,

And lifts her leafy arms to pray;

A tree that may in summer wear

A nest of robins in her hair;

Upon whose bosom snow has lain;

Who intimately lives with rain.

Poems are made by fools like me,

But only God can make a tree.

. . .

Written in 1913, when Kilmer was 26 years old, “Trees” would become his most famous poem – sentimental, yes, a breeze to memorize, true, and popular among several generations of Americans and Canadians for its sincere tone, its plain heartfelt-ness (and with God mixed into the verse). Joyce Kilmer’s life was brief. He worked for Funk and Wagnalls Dictionary updating definitions of ordinary English-language words at a nickel a pop. When he had the chance to enlist during The Great War he was over to France in a jiffy, where he died from a German sniper’s bullet and was remembered by the men of his regiment for his valour and leadership abilities as sergeant.. . .

Versiones/interpretaciones en español: Alexander Best

. . . . .

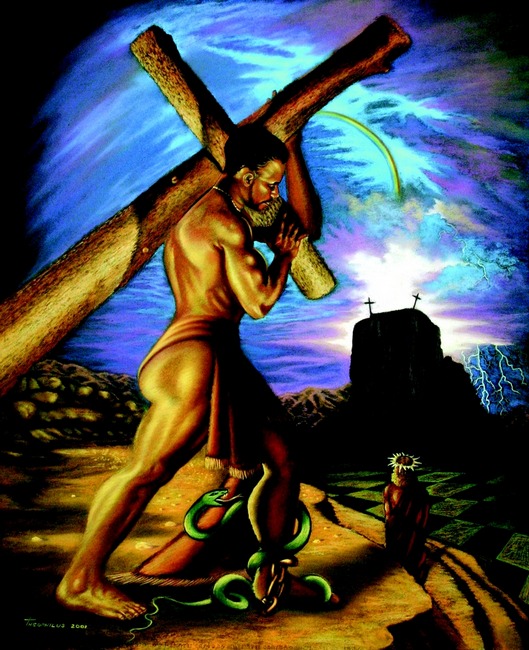

“Yo cumplo mi encuentro con La Vida” / “I keep Life’s rendezvous”: Poemas para Viernes Santo / Good Friday poems: Countee Cullen

Posted: March 29, 2013 Filed under: Countee Cullen, English, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: Black poets, Good Friday poems, Poemas para Viernes Santo, Poetas negros Comments Off on “Yo cumplo mi encuentro con La Vida” / “I keep Life’s rendezvous”: Poemas para Viernes Santo / Good Friday poems: Countee Cullen

Countee Cullen (Poeta negro del “Renacimiento de Harlem”, E.E.U.U., 1903-1946)

“Habla Simón de Cirene”

.

Nunca me habló ninguna palabra

pero me llamó por mi nombre;

No me habló por señas,

y aún entendí y vine.

.

Al princípio dije, “No cargaré

sobre mi espalda Su cruz;

Sólo procura colocarla allá

porque es negra mi piel.”

.

Pero Él moría por un sueño,

Y Él estuvo muy dócil,

Y en Sus ojos hubo un resplandor

que los hombres viajarán lejos para buscar.

.

Él – el mismo – ganó mi piedad;

Yo hice solamente por Cristo

Lo que todo el Imperio romano no pudo forjar en mí

con moretón de látigo o de piedra.

. . .

Countee Cullen (1903-1946)

“Simon the Cyrenian Speaks”

.

He never spoke a word to me,

And yet He called my name;

He never gave a sign to me,

And yet I knew and came.

At first I said, “I will not bear

His cross upon my back;

He only seeks to place it there

Because my skin is black.”

But He was dying for a dream,

And He was very meek,

And in His eyes there shone a gleam

Men journey far to seek.

It was Himself my pity bought;

I did for Christ alone

What all of Rome could not have wrought

With bruise of lash or stone.

.

Luke 23:26

“And as they led Him away, they laid hold upon one Simon, a Cyrenian, coming out of the country,

and on him they laid the cross, that he might bear it after Jesus”.

. . .

“Tengo un encuentro con La Vida”

.

Tengo un encuentro con La Vida,

durante los días que pasen,

antes de que pasen como un bólido mi juventud y mi fuerza de mente,

antes de que las dulces voces se vuelvan mudas.

.

Tengo un ‘rendez-vous’ con Esta Vida.

cuando canturrean los primeros heraldos de la Primavera.

Por seguro hay gente que gritaría que sea tanto mejor

coronar los días con reposo en vez de

enfrentar el camino, el viento, la lluvia

– para poner oídos al llamado profundo.

.

No tengo miedo ni de la lluvia, del viento, ni del camino abierto,

pero aún tengo, ay, tan mucho miedo, también,

por temor de que La Muerte me conozca y me requiera antes de que

yo cumpla mi ‘rendez-vous’ con La Vida.

. . .

“I have a rendezvous with Life”

.

I have a rendezvous with Life,

In days I hope will come,

Ere youth has sped, and strength of mind,

Ere voices sweet grow dumb.

I have a rendezvous with Life,

When Spring’s first heralds hum.

Sure some would cry it’s better far

To crown their days with sleep

Than face the road, the wind and rain,

To heed the calling deep.

Though wet nor blow nor space I fear,

Yet fear I deeply, too,

Lest Death should meet and claim me ere

I keep Life’s rendezvous.

. . .

Countee Cullen produced most of his famous poems between 1923 and 1929; he was at the top of his form from the end of his teens through his 20s – very early for a good poet.

His poems “Heritage”, “Yet Do I Marvel”, “The Ballad of the Brown Girl”, and “The Black Christ” are classics of The Harlem Renaissance. We feature here two of Cullen’s lesser-known poems

– including Spanish translations.

. . . . .

Traducciones del inglés al español: Alexander Best

“The Last Supper or: From now on, the worms speak for him” / “La Última Cena”

Posted: March 29, 2013 Filed under: English, Mario Meléndez, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on “The Last Supper or: From now on, the worms speak for him” / “La Última Cena”Mario Meléndez (nace/born 1971, Chile)

“La Última Cena” / “The Last Supper or: From now on, the worms speak for him”

.

Y el gusano mordió mi cuerpo

y dando gracias

lo repartió entre los suyos diciendo

“Hermanos

éste es el cuerpo de un poeta

tomad y comed todos de él

pero hacedlo con respeto

cuidad de no dañar sus cabellos

o sus ojos o sus labios

los guardaremos como reliquia

y cobraremos entrada por verlos”.

.

And the worm bit into my body

and, giving thanks,

divided it among his brethren, saying:

“Brothers,

this is the body of a poet

– take it, eat all of it,

but do this with respect,

careful not to harm the hair upon his head,

or his eyes, or his lips

– we will keep those as sacred relics

and we’ll charge an entry fee for people to see them.”

.

Mientras esto ocurría

algunos arreglaban las flores

otros medían la hondura de la fosa

y los más osados insultaban a los deudos

o simplemente dormían a la sombra de un espino.

.

While this was going on

some were arranging flowers,

others were gauging the depth of the grave,

and the boldest ones were busy offending the relatives and mourners

– or merely sleeping ‘neath the shade of a hawthorn tree.

.

Pero una vez acabado el banquete

el mismo gusano tomó mi sangre

y dando gracias también

la repartió entre los suyos diciendo

“Hermanos

ésta es la sangre de un poeta

sangre que será entregada a vosotros

para el regocijo de vuestras almas

bebamos todos hasta caer borrachos

y recuerden

el último en quedar de pie

reunirá los restos del difunto”.

.

But once the banquet was finished

the same worm drank my blood

and, also giving thanks,

shared my blood among the rest of those present,

saying:

“Brothers,

this is the blood of a poet,

blood consecrated for you

for the sake of your souls’ rejoicing

– drink all of it until you fall down drunk,

that you may remember:

in high heaven it’s a stubborn fact –

you will be reunited with the remains of the deceased.”

.

Y el último en quedar de pie

no solamente reunió los restos del difunto

los ojos, los labios, los cabellos

y una parte apreciable del estómago

y los muslos que no fueron devorados

junto con las ropas

y uno que otro objeto de valor

sino que además escribió con sangre

con la misma sangre derramada

escribió sobre la lápida

“Aquí yace Mario Meléndez

un poeta

las palabras no vinieron a despedirlo

desde ahora los gusanos hablaremos por él”.

.

And the last-gasp fact…

not only was it the ‘joining-together’ of all of them

with the remains of the deceased –

his eyes, his lips, the hair upon his head,

an appreciable part of his stomach,

the thighs which were not devoured,

together with his clothing

and one or another item of value –

but that, moreover,

it was written in blood – that same spilt blood –

he wrote upon his own headstone:

“Here lies Mario Meléndez, a poet.

Words never came to bid him farewell,

and from now on,

the worms speak for him.”

.

Traducción/interpretación en inglés: Alexander Best

. . .

Mario Meléndez studied journalism at La República University in Santiago, Chile. In 1993 – the bicentennial of Linares – he won that city’s Municipal Prize for Literature. In 2003, in Rome, he was made an honorary member of the Academy of European Culture, after speaking at the First International Gathering for Amnesty and Solidarity of The People. In 2005 he won the Harvest International Prize for best poem in Spanish from the University of California Polytechnic.

Alan Clark: “Guerrero and Heart’s Blood” / “Guerrero y Sangre del Corazón”

Posted: March 19, 2013 Filed under: Alan Clark, English, Spanish Comments Off on Alan Clark: “Guerrero and Heart’s Blood” / “Guerrero y Sangre del Corazón”Un extracto en cinco voces – de “Guerrero y Sangre del Corazón” por Alan Clark:

.

Guerrero habla:

“Yo soy Gonzalo Guerrero, Capitán al servicio de Nachancán, Señor de Chetumal. Casado. Un padre. Cortado y cubierto de cicatrices y decorado con tintes. Un guerrero conocido entre mi gente como “hombre valiente”.

Yo no soy aquel que fui. En Palos, donde nací, mi anterior familia vive todavia, a menos que haya habido una plaga o una guerra. Mi padre y mi madre quizás vivan aún. Pero lo dudo.

Había un árbol alto junto a la vieja casa, al que mi hermano Rodrigo y yo solíamos atar una soga, que dejábamos caer al suelo, luego trepábamos hasta lo más delgado del tronco y -pas!- soltábamos la cuerda y volábamos en el cielo cálido y azul entre el estruendo de las hojas. Les hacíamos jugarretas.

A nuestras hermanas, las espíabamos cuando se bañaban, y detestábamos la escuela y al cura de la iglesia, que nos pegaba en el nombre de Dios.

Ahora estoy muy lejos de todo eso. Soy algo así como un noble, y jefe en tiempo de guerra. Ahora escucho mensajes en el humo de papeles ensangrentados que los sacerdotes encienden en la cima de los templos, papeles empapados en la sangre de sus propios miembros desgarrados. A veces la sangre es mía. Me toca oficiar cuando se hace un sacrificio, y sentir como los cielos y la tierra cambian y se estremecen y se reconstruyen a sí mismos con el advenimiento de la más suprema de las ofrendas sagradas. Como un pequeño trozo del esclavo, del niño, o del cautivo, que quizás yo mismo haya sometido con estas manos. Su terror anticipa el temblor aún mayor del mundo una vez que hayamos cortado y ofrendado y ungido. Me tomó mucho tiempo vencer mi propio terror y repulsión.

El gran Señor Nachancán, quien me tomó luego que escapé de su espantoso vecino y enemigo, vió en mi lo que quizás yo nunca hubiese visto por mi mismo. Me dijo que de una sola mirada, cuando fui llevado ante él, consumido y cubierto con mis andrajos de esclavo, supo mi lugar en los cielo, a pesar de mi apariencia. Incluyendo mi negra barba crecida y despareja.

. . .

Habla Nachancán:

“Ja. Las noticias sobre los extranjeros habían llegado a mí aún antes de que desembarcaran. Mis mensajeros esparcieron las nuevas. Lo recuerdo bien. Conejo Dos pidió las jaulas y los postes. Kinich Ek quería a las dos mujeres. Le dimos una. Le arrancaron el corazón antes de terminar el día, como a los otros tres. Yo tomé una, para que ayudara a mi esposa y para interrogarla. Hace ya un año que murió. Mi mujer es muy dura con sus esclavos. Pero los alimenta bien.

Eran un grupo raro. Les arrancamos sus andrajos impregnados de sal para ver si eran humanos, como nosotros. Nuestros magos y sacerdotes los atormentaban y les lanzaron hechizos de humo. Eran hombres, pero blancos y peludos. Y hablaban un idioma que no pudimos entender, y temblaban en el calor, implorándonos por señas que les diéramos agua y comida. Los pusimos en jaulas para que engordaran. No sabían mal, cocidos con chiles. Nada mal…

Sólo quise uno para mí. Fue primero con Conejo, que es cruel y estúpido, hasta que un día huyó y vino a mí. Desde el primer momento vi en él a alguien de provecho, alguien para nosotros. Mi lengua se adelantó a mi voluntad: dénmelo.

.

Habla Nachancán:

Extraño pocas cosas. Mi naturaleza es afable como esta sonrisa que ven. Y la risa siempre a flor de labios – lo que a veces ha hecho pensar a mis enemigos que estoy loco…sus cabezas no sonríen desde donde nos miran, sobre los escalones del templo. Pronto sus ceños fruncidos desaparecerán. Y entonces las moscas se reirán para mí.

Cuando llegó, el extranjero Guerrero, noté que su presencia alteraba mucho a mi hija, Mucuy, que le lanzó una mirada de odio, y luego le ignoró. Cuando llegó la siguiente oportunidad de sangrarme, pedí a los dioses que me dieran su respaldo. Las serpientes no dicen más que lo necesario.

. . .

Aguilar habla:

¿Y dónde está la maldita gloria para el que va a morir? Esta noche se van a llevar a uno de mis pupilos a la piedra. Su nombre es Pop Che. Durante semanas he estado llevándole agua y comida. Pero no quería comer. ¿Puede alguien culparlo? Y, oh Dios, sólo es un muchachito. Un granjero que un día se puso su camisa de algodón, desenpolvó su lanza, se puso algunas plumas en el pelo –y dejó a su mujer, a sus hijos, y a su anciana madre, para ir a pelear contra Nachancán y los soldados perdidos de Guerrero. Y ahora está aquí con nosotros. Todo mi coraje es inútil. ¿Y qué han logrado todas mis plegarias por él? Le darán la bebida, lo pintarán, y…

.

Pero ¡ay!, la sangre de mi corazón se va con él. Qué puedo hacer más que seguir rezando y llevarle más agua. ¿Decirle que el dios que ni siquiera acepta lo espera en los cielos para tomarlo en sus brazos celestiales? Ya vienen. Los tambores han comenzado a sonar. Ay, ese sonido me llega como si me golpeasen a mí. Estoy asqueado y harto de todo.

.

Aguilar habla:

No es tan malo ser esclavo. No es tan malo estar vestido con harapos desechados, ser pateado e insultado y golpeado hasta morir por gente perdida en supersticiones. Y admite que hay cierto arte en lo que hacen, y a veces gran belleza en sus vestidos tejidos, y en sus vasijas de barro pintado. Inclusive en el brillante decorado de las piedras y del oro con los que se adornan, y con los que a veces se perforan grotescamente. Sus canciones y cantos, el embrujo de los tambores y las flautas, las trompetas y las caracolas. No soy ciego ni sordo a estas cosas. ¡Pero sus dioses me consternan, representan el horror del deseo de sangre del demonio, y en el momento del sacrificio quisiera aullar, conjurar la venganza de Dios para que desmenuzara hasta hacerlos polvo estos templos blanqueados de cal y manchados de sangre! Dios salve nuestras almas.

. . .

Alicia habla:

¡Gonzalo! ¡Gonzalo! Los viejos ojos de tu madre están puestos en ti. Dondequiera que estés, estos ojos te acompañan. Hoy me puse a quemar algunas ramas del viejo árbol que da las naranjas que tanto te gustaban. Esas ramas ya están viejas y secas porque hace ya tanto que te fuiste. ¿Para siempre? Y porque tu padre ha muerto. Murió la muerte rápida y fea de la plaga –su lengua estaba negra y gruesa, se ahogaba- y no podía decir tu nombre. Tu hermano y tus hermanas están bien. Eres tío de una horda de niños.

Gonzalo. Por el amor que te tengo, te entiendo y te veo, dondequiera que estés. En las cavernas de tu corazón, en el poder de tus brazos y de tu mente, siempre me he maravillado. Tal como ahora que sueño y te veo. Y no me preocupo, sólo te extraño. ¿Será que te has ido para siempre de tu hogar, de nosotros? En donde tu padre te engendró de la pasión por su madre, que te trajo con alegría y dolor, mi primer hijo. Mi amor por ti, buen hijo errante, jamás ha mermado, ni lo hará jamás, aún después de nuestra muerte terrenal. Y ahora, para verte, sólo me queda esperar ese día, porque estos viejos ojos ya no lo ven todo.

Con esta vieja mano alzo una naranja al sol, y huelo en el humo que se levanta de las viejas ramas de tu árbol favorito, el sabor de la fruta que aún perdura en él. Y con las cenizas que queden, abonaré mi jardín en tu nombre. Buen hijo.

. . .

Mucuy habla:

Acerca tuyo, esposo mío, déjame hablar. Tu fértil esposa ha yacido despierta junto a ti muchas noches, sintiéndose feliz y afortunada. Que al principio no podía entender. Tu eras un extraño, y –casi- parecías un animal. Tu cuerpo enfermo y pálido, tus mejillas cubiertas de pelo, y tu hablar rápido y extraño, me descorazonaba. Cuando me miraste por primera vez, me estremecí y sentí que gritaba por dentro, así que le pedí a mi madre que me explicara porque me causabas tanta confusión, que me dijera qué y quién eras, un hombre que daba tan mala impresión en todo. Si bien uno del que mi padre se expresó como si fuese su propio hijo. Pero finalmente el amor se reveló en mi corazón. Y te encontré esperándome como el sol cuando llueve, y crecí, y aprendí que nuestras caricias arrojaban una luz secreta mientras la luna aguardaba en su oscuro mundo para brillar sobre lo que surgiera. En ti encuentro, dentro de mis más ardientes deseos y mi famoso carácter, toda la suavidad y el peligro que toda mujer anhela, y escuché tus palabras que vagaban como los inseguros pasos de la niñez hacia mí, y temblé al sentir como te arrimabas a mí como las aguas del mar de Cozumel, que llegan a azotar día y noche, como el temblor de mis nervios mientras me preparo a mi festín de ti, con mis lenguas y dientes deseando tu sabor.

.

Así he llegado a conocerte, y de ello nació esta mujer fuerte, que en su pasión nutre la vida de toda su gente… porque antes sólo era buena para esperar, hasta que el mar te arrojó de quien sabe donde, más allá de donde los soles salen para alumbrar los días. Tu viniste de algún otro lugar, de donde te enviaron los dioses y las diosas.

.

Mucuy habla de su intimidad con Guerrero:

Ay, tu lengua tropezando y enredándose con la mía, pareciera haberse convertido en aquella con la que naciste. Te veo caminar entre los hombres, algunos de ellos hermanos míos, los mejores hijos de Nachancán y de la madre que tengo la bendición de poder ver

todos los días, y veo que tú eres uno de nosotros tanto como es posible, y por eso perdono tan fácilmente tus cuestionamientos, tus sueños, mi apetito nocturno, para ayudar a revelarte, mientras los años se desenredan en nuestros cuerpos acostados, o caminando entrelazados tal como nuestros espíritus lo están, y entender tus necesidades antes que tú mismo. Hemos susurrado mucho más allá del tiempo en que los pájaros se van a dormir acurrucándose en sus alas, sobre el misterio de cómo llegamos a ser uno.

.

Mucuy habla sobre la necesidad de que Guerrero participe en los sacrificios:

¿Acaso no soy, querido esposo, padre de mi hija e hijos, también tu maestra en las cosas que tanto te hacen temblar? Al fin ascenderás las escaleras del templo, y te infligirás las heridas que sangren y alimenten los fuegos de lo que verás, las cosas que ves tú mucho más claramente que yo, que te digo: mi tierno y sobrecogedor hombre –¡ve con papá Nachancán y con Pool, y los demás, esta noche, y sé un hombre! Nadie espera que puedas saber qué tanto dependen de ti este ritual y esta vida, aunque me hayas dicho que va contra tu formación. Sé valiente, mi querido esposo, y conoce la sangre que se derramará sobre ti; saboréala si puedes. El muchacho nació para esto. Su corazón fue medido desde el comienzo del mundo –para esto. El dios cuyos días han vuelto a llegar, ha hablado, y mantiene unidas las piedras sobre las que reposa –para esto. Espera que nuestros ojos se glorifiquen en estas muertes –por él. Para que nosotros en él lo veamos y honremos.

.

Traducción del inglés al español: Lisa Primus

. . .

Gonzalo Guerrero (1470-1536) fue un marino español y uno de los primeros europeos que vivió en el seno de una sociedad indígena. Murió luchando contra los conquistadores españoles. Guerrero es un personaje porfiado porque se aculturó al punto de ser un jefe maya durante la conquista de Yucatán. En México se refieren a él como Padre del Mestizaje. Presentamos aquí la obra del escritor y pintor Alan Clark – “Guerrero and Heart’s Blood /Guerrero y Sangre del Corazón” (Henning Bartsch, México, D. F., 1999) con la traducción de Lisa Primus.

An excerpt in five voices – from “Guerrero and Heart’s Blood” by Alan Clark:

.

Guerrero speaks:

I am Gonzalo Guerrero, Captain in the service of Nachancan, Lord of Chektumal. Married. A father. Cut and scarred and decorated with inks. A warrior, who is known among my people as a “brave man”.

.

I am no more what I used to be. In Palos, where I was born, my old family still lives. Unless there’s been a plague, or a war. My father and mother may still be alive, my brothers and sisters who I played with, and tormented. Maybe nothing has changed. Maybe everything. But I doubt that.

.

There was tall tree by our old house, my brother Rodrigo and I would tie a rope to, then pull it down to the ground, climb onto its thin trunk, and snap! Let the rope go and fly into the hot blue air in a clamor of leaves. We played tricks on our sisters, spied on them in their baths when we were all older. And hated the fathers of the church, who beat us in the name of God.

.

Now I’m far away from all of that. I am a kind of lord myself, and a chief in time of war. Now I harken to the messages in the smoke of blood stained papers the priests ignite on the temple tops. Papers drenched in their own blood, from their own shredded members. Sometimes the blood is my own. I am in attendance when a sacrifice is made, and feel the earth and the skies change and quiver and recast themselves at the advent of this most supreme offering. I eat some small piece of the slave or the child or the captive I myself, with these same hands, may have subdued. Their terror anticipates the wide world’s trembling when we have cut and offered and anointed. It took a long time to get past my own terror and revulsion.

.

The great Lord Nachancan, who took me in after I had escaped from his horrific neighbor and enemy, saw in me what I had perhaps would never have seen, myself. He told me that from one look, as I was brought before him, worn out, in my slave’s rags, he knew my place in the heavens and was undeceived by my appearance otherwise. Even by my ragged, black beard.

. . .

Nachancan speaks:

Ha. The word about the strangers was in my ear before they landed. My messengers had run with the news. I remember it well. Two Rabbit called for the cages and the long poles. Kinich Ek wanted the two women. We gave him one. Her heart was out before the day ended. The other I took to help my wife, and to question. It was only a year ago she died. My wife works her slaves very hard. But feeds them well.

.

They were a strange crew. We stripped them of their salty rags to see if they were human, like ourselves. Our priest and magician poked them all over and spelled them with smokes. They were men, but white and hairy, and spoke in a tongue we didn’t understand. They shivered in the heat, begging us by signs for food and drink. We put them into the cages. They did not taste too bad, cooked with chilies. Not too bad…

.

Only one I wanted for myself. He went first to Rabbit, who is stupid and cruel, until the day he ran to me. From the first, I saw him as someone of use, someone for us. My tongue spoke out ahead of me: Give me him.

.

There is little I miss. My nature is this smile you see, and the laughter that brims in my blood. Which has sometimes made my enemies think I am a fool. Their heads don’t smile from where they stare out on the temple steps. Soon enough their sagging frowns are gone, and then the buzzards make a laughing sign to me.

.

When he came, the stranger, Guerrero, I could see the sight of him upset too much my daughter, Mucuy. She glowered and shot an arrow from her eyes, and then would look no more. When I next bled myself, I asked the gods to second me in what I’d seen. The serpent speaks no more than we can know.

. . .

Aguilar speaks:

And where is the glory for the one who’s going to die? They’re taking a ward of mine up to the stone tonight. His name is Pop Che. For weeks I’ve brought him his food and water. But he won’t eat. Can you blame him? And, O God, he’s only a little man, a farmer who put on his cotton shirt one day, and dusted off his spear, left his wife and his children, and old mother, to go fight against Nachancan and the lost Guerrero’s soldiers.

.

And now he’s here with us. All my raging is useless. What have my prayers for him accomplished? They’ll give him the drink, paint him and feather him, and then….

.

But O! my heart’s blood goes with him. What else can I do? Tell him that the God he doesn’t even want, is waiting in heaven to hold him in his heavenly arms?

.

Here they come. The drums have started. Ah! That sound pounds into me as if it was me they were striking. I am sick and weak with everything.

.

It is not so bad, to be a slave. It is not so bad to be dressed in rags, to be kicked and insulted and worked almost to death by people lost in their superstitions. I will even admit there’s a certain art in what they do, and sometimes great beauty in their woven cloths, in their painted earthenwares. Even in the glittering ornateness of the stones and gold with which they adorn themselves. And are sometimes pierced to grotesqueness by!

.

I am not blind and deaf to these things. But their gods dismay me, are the horror of the Devil’s own wish for blood. And at the moment of sacrifice, I want to howl! and call God’s vengeance down to crumble to dust these whitewashed and bloodstained temples. God save all our souls…

. . .

Alicia speaks:

Gonzalo. Gonzalo. Your mother’s eyes are on you. Wherever you are, these eyes are on you. Today I’m burning some branches from the old tree that bears the fruit, the oranges you love, branches old and dry now because you’ve been gone so long. Forever?

.

Your father is dead. He died the fast and ugly death of plague, and couldn’t even speak your name. Your brothers and sister are well. You are now the uncle to a horde of growing kin.

.

Gonzalo. In my love for you, I understand and see you, wherever you may be. Of the passions of your heart, of the power of your arms and mind, I have always been in wonderment. This is no less so this hour I dream and see you. O, and I do not worry, but only miss you so! Forever gone from us and this, your home? Where your father seeded you in passion with his wife, who bore you happily in pain. My first born child.

.

My love for you, good son and wanderer, has never ceased, nor will it ever, even beyond our earthly dying. And now I only wait to see you then, because these old eyes cannot see everything they wish to.

.

With this hand I lift an orange to the sun, and smell in the smoke that rises from the worn out branches of your favorite tree, the savor of the fruit that lived within. And with the ashes left, will feed my garden in your name. Good son.

. . .

Mucuy speaks:

About you, my husband, let me speak. Your fertile wife has lain awake beside you many nights, and felt a wonder at her fortune. Which at first she could not feel. You were a stranger, almost, it seemed, a beast. Your body was sick and pale, your cheeks filled with hair, your strange, fast words dismaying me. When you first looked at me, I shivered and grew shrill, and asked my mother to explain the confusions you provoked, to tell me who and what you were, a man so alrogether wrong. But one of whom my father spoke as if you were a son.

.

But then my love unclouded in my heart. I found you waiting there for me like sun and summer rain. And I grew, and knew our touches cast in secret lightness while the moon was waiting in her darkest world to shine on what would be.

.

I found in you, inside my fiercest wish and famous temper, all my softness, and the danger any woman wants. And listened to your words, which wandered like the hesitating steps of childhood toward me, and trembled for the way you washed against me, like the waters of the sea off Cozumel, coming in to thunder day and night, like the trembling of my nerves as I’m edging toward my feast of you, whose taste my tongues and teeth desire.

.

Like this, I’ve come to know you, and out of this become the woman who is strong, and in her passion feeds the life of all her people. Because before, I was only great in waiting – when you washed ashore from nowhere, from somewhere out beyond where all the suns rise up to gleam awake the days. From somewhere else you came, the goddesses and gods had sent you.

.

And O, your stumbling tongue in tangling with my own, has since become as if it was the one you hatched with. I watch you walk among the men, some of them my brothers, the strongest sons of Nachancan, and the mother who I live in blessedness to see each day, and know that you are one of us as much as you can be, your dreams my nightly appetite to help explain to you, as the years unravel in our bodies lying down, or walking braided as our spirits are, and understand your needs before you do yourself. We’ve whispered long past the hour the birds have gone to sleep inside their wings, about the mystery of why we came to be as one.

.

Mucuy speaks about his need to attend the sacrifices:

Am I not, dear husband, father of my daughter and sons, also yet your teacher in the things that make you tremble so? At last! To climb the temple steps and prick upon yourself the wound that bleeds, and feeds the fire of what you’ll see there, the things you see so much more than I!

.

Who say to you, my tender, overwhelming man: Go to, with father Nachancan, and Pool, and the others on this night and be a man! No one expects that you can know how much this ritual, how much this life depends on you, you have told me goes against your way. Be brave, my darling husband, and know the blood that will spatter onto you, and taste it if you can. The boy is born for this. His heart is measured since the world began, for this. The God whose day has come around again, has spoken, and commands the stones themselves he rests upon, to worship him.

. . . . .

Alan Clark writes:

Gonzalo Guerrero (1470-1536) was a sailor from Palos de la Frontera, Spain, and was shipwrecked around 1511 while sailing from Panama to Santo Domingo with a dozen or so others. They drifted for a couple of weeks before Caribbean currents brought them to the shores of what is now the State of Quintana Roo in modern-day México where they were captured by Maya people and put into cages. Eight years later when Hernán Córtes arrived at Kùutsmil (Cozumel ) to begin what would be the Conquest of México, there were only two from this shipwreck still alive – Guerrero, and a priest named Jerónimo de Aguilar. Guerrero was by this time married with children, the first mestizos in México, and was a chief in time of war for the Maya lord Nachancán. Aguilar was a slave living in another city state.

.

I’ve attempted, through Guerrero’s wife, Mucuy – and through Nachancán, Aguilar, Guerrero’s mother in Spain (whom I’ve called Alicia), and of course through Guerrero himself – to give both the inner and outer picture/story of this man, a people, and the times in which they lived.

.

Guerrero and Heart’s Blood was published in 1999 by Henning Bartsch, México City. Although I never had the theatre in mind when I was writing it, Guerrero has had a variety of stagings in both the U.S.A. and México. Heart’s Blood is an accompanying story, told by Aguilar, and was performed in both Spanish and English in México as an adapted monologue by Alejandro Reza, with a score for cello by Vincent Carver Luke. The translation into Spanish is by Lisa Primus. My painting, on the cover of the original book, is called “Blood and Stone”.

. . . . .

Poemas para El Día Internacional de la Mujer: una poetisa anishinaabe que deseamos honrar: Joanna Shawana / Poems for International Women’s Day: an Anishinaabe poet we wish to honour: Joanna Shawana

Posted: March 8, 2013 Filed under: English, Joanna Shawana, Joanna Shawana: poetisa anishinaabe/Anishinaabe poet, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: Poemas para El Día Internacional de la Mujer, Poems for International Women's Day Comments Off on Poemas para El Día Internacional de la Mujer: una poetisa anishinaabe que deseamos honrar: Joanna Shawana / Poems for International Women’s Day: an Anishinaabe poet we wish to honour: Joanna Shawana

ZP_Manitoulin Island artist Daphne Odjig_Echoes of the Past_Daphne Odjig_Pintora indígena de la Isla de Manitoulin_Ecos del Pasado

Joanna Shawana / Niimkiigiihikgad-Kwe

(Anishinaabe poet from Wikwemikong, of the Ojibwe-Odawa First Nations Peoples, Mnidoo Mnis/Manitoulin Island, Ontario)

“Grandmother Moon”

.

During this cold dark night

Grandmother Moon sits high

Above the sky

.

Our Grandmother

Surrounded with stars

Emphasizing the life of the universe

.

As the night comes to end

Our Grandmother Moon slowly fades

Over the horizon

.

To greet Grandfather Sun

To greet him

As the new day begins

.

Grandmother Moon will rise again

She will shine and guide me on my path

As I walk on this journey.

. . .

Joanna Shawana / Niimkiigiihikgad-Kwe

(Poetisa anishinaabe de Wikwemikong, Mnidoo Mnis/Isla de Manitoulin, Ontario, Canadá)

“La Luna – Mi Abuela”

.

Durante esta noche fría y oscura

La Luna Mi Abuela se sienta

Alta en el cielo

.

Nuestra Abuela

Está rodeada de estrellas

Que hacen hincapié en la vida del universo

.

Como cierra la noche

Lentamente Nuestra Abuela La Luna destiñe

Encima del horizonte

.

Para dar la bienvenida al Abuelo El Sol

Para saludarle

Como comienza el nuevo día

.

Ella saldrá de nuevo, La Luna-Abuela,

Brillará y me guiará en mi camino

Como ando en este paso.

. . .

“All I Ask”

.

My fellow woman

My sisters

I am weak

I am hurt

All I ask of you is

Please

Hear what I have to say

Hear what I have to share

I am not here

To be looked down

I am not here

To be judged

For what had happened to me

All I ask of you is

Please

Hear what I have to share

My fellow women

My sisters

Listen to my words

See the pain in my eyes

All I ask of you is

Please

Hear what I have to say

Hear what I have to share

Help me

To get through my pain

Help me

To understand what is happening

Help me

To be a better person

So please

Hear what I have to say

Hear what I have to share.

. . .

“Todo lo que te pido…”

.

Mi compañera

Mis hermanas

Soy débil

Estoy dolida

Todo lo que te pido es

Por favor, escucha lo que tengo que decir

Escucha lo que tengo que compartirte

No estoy aquí

Para ser mirada por ustedes por encima del hombro

No estoy aquí

Para ser juzgada de

Lo que me había pasado

Todo lo que les pido es

Por favor, escuchen lo que tengo que compartirles,

Mis compañeras, mis hermanas,

Escuchen mis palabras

Vean el dolor en mis ojos

Todo lo que les pido es

Por favor,

Escuchen lo que tengo que decir

Escuchen lo que tengo que compartirles

Ayúdame a

Superar mi sufrimiento

Ayúdenme a

Comprender lo que pasa

Ayúdenme a

Ser una mejor persona

– Entonces,

Por favor,

Escucha lo que tengo que decirte,

Escuchen lo que tengo que compartir con ustedes…

. . .

“Hidden”

.

Hidden secrets

Hidden feelings

Hidden thoughts

.

Why do people need to hide

Their secrets

Their feelings and thoughts?

.

What are people afraid of?

Afraid of their own secrets

Afraid of their own feelings and thoughts

.

How can one person reveal?

To reveal their secrets

To reveal their feelings and thoughts

.

There is no reason to hide their secrets

There is no reason to hide their feelings

There is no reason to hide their thoughts.

. . .

“Escondido”

.

Secretos escondidos

Sentimientos escondidos

Pensamientos escondidos

.

¿Por qué la gente necesita ocultar algo?

Ocultar sus secretos, sus sentimientos y sus pensamientos

.

¿De qué tiene miedo la gente?

Tiene miedo de sus propios secretos,

Tiene miedo de sus corazonadas y sus ideas

.

¿Cómo revele una persona?

A revelar sus secretos

A revelar sus pensamientos

.

No hay razón para ser una tumba

No hay razón para engañarse a sí mismo sus sentimientos

No hay razón para esconder sus pensamientos.

. . .

“Wandering Spirit”

.

This wandering spirit of mine

Wanders off to the world of the unknown

The unknown of today and tomorrow

.

This wandering spirit of mine

Waits to hear your voice

Waits to listen for what will be said

.

This wandering spirit of mine

– Help me to discover the unknown

– Help me to understand

What the unknown needs to offer

.

Help this wandering spirit

That wanders off to the world of the unknown

That wonders what the future holds

.

This wandering spirit of mine

– Help me find peace and harmony

– Help me find tranquillity in life.

. . .

“Espíritu vagabundo”

.

Mi espíritu vagabundo

Se aleja al mundo de lo desconocido

Lo desconocido de hoy, de mañana

.

Este espíritu mío errante

Está aguardando tu voz

Está aguardando por lo que diremos

.

Espíritu mío, espíritu vagabundo

– Ayúdame a descubrir lo desconocido

– Ayúdame a entender

Lo que lo desconocido necesita ofrecerme

.

Ayúda a este espíritu errante

Que se aleja al mundo de lo desconocido

Y que se pregunta lo que va a contener el futuro

.

Este espíritu mío, mi espíritu andante

– Ayúdame a encontrar la paz y la armonía

– Ayúdame a encontrar la tranquilidad en la vida.

“Walk with Me”

.

Come and walk with me

On this path

Which I am walking on

.

We might slip and fall

To the cycle

That we once lived in

.

Let us

Help each other to understand

What we have been through

.

Let us walk together

Come and hold my hand

Hold it tight and never let go

.

Come and walk with me

Let us find what our future holds for us

Let us walk together on this path.

. . .

“Camina conmigo”

.

Ven – camina conmigo

A lo largo de este camino

Donde estoy caminando

.

Resbalemos y caigamos

Al ciclo

Que estaba nuestra vida

.

Ayudémonos a comprender,

La una a la otra,

Lo que salimos adelante, lo que sobrevivimos

.

Caminemos juntos,

Ven – toma mi mano –

Agárrate bien – nunca suéltame la mano

.

Ven – camina conmigo

Busquemos lo que habrá para nosotros en el futuro

Caminemos juntos en este camino.

. . .

Joanna Shawana moved down to Toronto in 1988. She began writing in 1994. A single parent, and now a grandmother, she has worked for an agency providing services to Native people in the city – Anishnawbe Health Toronto. Her bio. from her book of poems Voice of an Eagle states: A Catholic upbringing clashed with Native heritage teachings, which confused her path. However, through the years she gained more knowledge from her Native elders and began to clearly understand what it meant to be Nishnawbe Kwe (Native Woman). Thus, her journey in stabilizing her identity began… Joanna writes: ” When I look back and see what I have left behind, inside I cry for the little girl who witnessed that life, the teenager who was abused, and the woman who almost gave in, but I know now that my inner strength will never allow me to leave my path. Healing is a continuous part of life and it will be so until the day comes that the Creators call me. So as you travel along your path, remember – do not give in or give up! ”

.

Joanna Shawana fue víctima de mucho maltrato durante su juventud, también como una mujer joven. Desde 1988 ha vivido en la ciudad de Toronto donde trabaja con la agencia indígena Fortaleza de Anishnawbe Toronto. Dice: ” La curación es una parte continua de la vida y ésa será hasta que el día que me llamarán los Creadores. Entonces, mientras viajas en tu camino, recuerda – ¡no te des por vencido y no dejes de intentar! ”

.

Translations into Spanish / Traducciones en español: Alexander Best

. . . . .