Zócalo Poets

Nos vemos en el Zócalo / Meet Us in the Square

.

On Broadway

The Barrier

The City’s Love

For one brief golden moment rare like wine,

When I Have Passed Away

. . .

The Harlem Dancer

Outcast

. . .

A Prayer

. . .

Me Bannabees

King Banana

. . .

. . .

Taken Aback

. . .

A Midnight Woman to the Bobby

“WIFE, de parson’s prayin’,

. . .

. . .

Killin’ Nanny

Strokes of the Tamarind Switch

. . .

. . .

Pregunta número 2

. . .

. . .

Calle número 125 (en Harlem)

. . .

. . .

“Blues at Dawn”

. . .

. . .

Hermanos

Astilla

“Sliver”

. . .

Folks, I’m telling you:

Le Nègre parle des fleuves (1921)

Mon âme est devenue aussi profonde que les fleuves.

Je me suis baigné dans l’Euphrate quand les aubes étaient neuves.

Moi aussi, je chante l’Amérique (1926)

.

.

. . .

Archives

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Categories

- 7 GUEST EDITORS

- A FEW FAVOURITES / UNA MUESTRA DE FAVORITOS

- #1 – ¡Nuestro Número Uno! Poemas en Quechua

- Audre Lorde: poemas traducidos

- Black Hairstory Month

- Black History Month 1

- Black History Month 2

- Brazilian women poets: new translations

- Bright Horizon by Ahmad Shamlu

- Cinco de Mayo: Then and Now

- Cinco poetas irlandeses

- Claribel Alegría: And I dreamt that I was a tree

- Claude McKay: Songs of Jamaica

- Contemporary poetry from Spain – outside 'the Canon'

- Cuban poetry and The Revolution

- Cuban women poets

- Cuento anaranjado: tallando una calabaza de Hallowe'en…

- Du Cake-Walk au Patinage artistique sur la glace…

- Emancípense de la esclavitud mental: Marcus Garvey + Bob Marley y su Canción de Redención

- Eva La Culpable…Was It All Eve's Fault?

- Faces and places: Canadian Gay heroes, sung and unsung

- Five 21st-century Iranian women poets

- Flags of Canada

- Frida + Diego: poems + pictures / pinturas + poemas

- Go on and up!: poems by Paul Laurence Dunbar

- Gwendolyn Brooks: poemas traducidos

- In all its breadth and ceaseless treasure: Lewis MacKinnon and the contemporary Gaelic poem

- Jesucristo el Gran Chamán: las pinturas de Norval Morrisseau / Jesus Christ the Shaman: the paintings of Norval Morrisseau

- Joanna Shawana: poetisa anishinaabe/Anishinaabe poet

- June Jordan: Poema sobre Intelecto para mis Hermanos y Hermanas

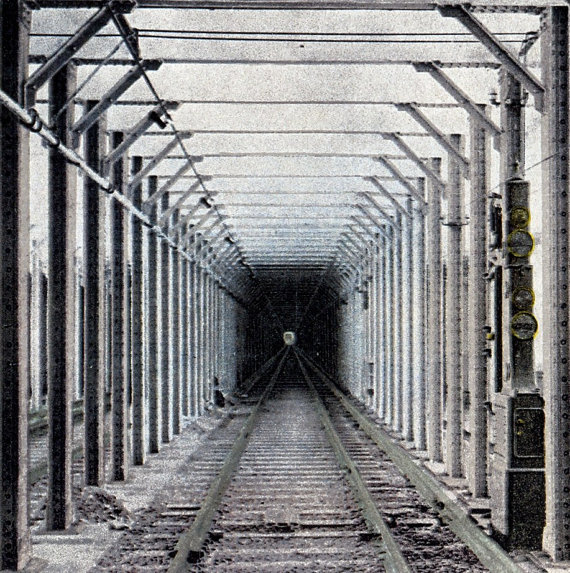

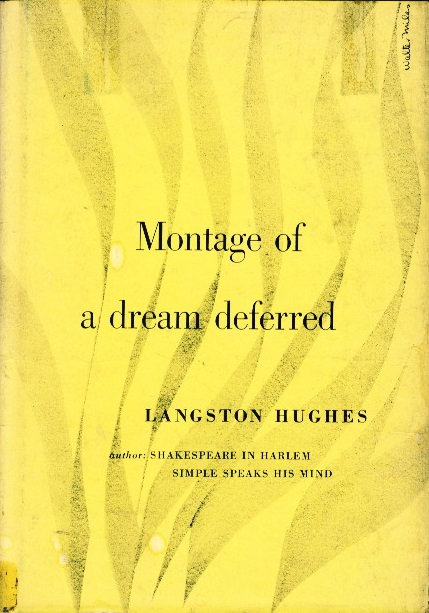

- Langston Hughes: poemas del poemario "Montaje de un Sueño Diferido" (1951)

- Lewis Carroll: Canción de Amor / A Song of Love

- Love poems and Blues poems – from The Harlem Renaissance

- Mi'kmaw I am: Poems of Rita Joe + We are the Dreamers

- Nezahualcoyotzin: in xochitl in cuicatl / Nezahualcóyotl: su "flor y canto"(poesía náhuatl) y poemas del siglo xxi – inspirados en él

- Ngày Quốc tế Phụ nữ : Thơ Việt Nam / Poems for International Women's Day : Vietnamese Voices

- Nicolás Guillén + el Yoruba de Cuba / the Yoruba from Cuba

- Orfeu Negro and the origins of Samba + Wilson Batista's “Kerchief around my neck” and Noel Rosa's “Idle youth”

- Pauline Johnson's "Flint & Feather"

- Peter Blue Cloud: Tales and Poems of Coyote

- Poemas de Amor del idioma maya

- Poemas de Amor del idioma zapoteco

- POEMAS DE AMOR EN QUECHUA

- Poemas de Amor – en el idioma quechua: Urqukunapa Yawarnin

- Poemas de amor en el idioma quechua: Ariruma Kowii

- Poemas de amor en la lengua quechua: Lily Flores Palomino

- Poemas de Amor en Quechua: akllasqa rimaykuna [ Qosqo Qhechwasimipi ]

- Poemas de amor en quechua: Yuyarillaway

- Poemas de amor quechua: Juan Wallparrimachi + José David Berríos + unos poetas bolivianos anónimos

- Sunqupa Harawinkuna por Kusi Paukar

- Poemas para el Ciclo de Vida: Anne Spencer

- Poemas para el Día de San Patricio: Amor y el Poeta

- Rabindranath Tagore: "Ella" + "El Camino Cerrado"

- Reesom Haile: La voz vivaz de Eritrea / the lively voice of Eritrea

- Retratos por José Guadalupe Posada

- Saeed Jones: Disposición de Sueño y A Ser Una Gacela

- The Road Before Us: Gay Black Poets from a generation ago

- Translator's Whimsy: Song Lyrics / Extravagancia del traductor: Letras de canciones traducidas por Alexander Best

- World AIDS Day: 25th Anniversary Poems in 4 Languages

- Writer-Artist-Dreamer: Alootook Ipellie

- Civil War poetry from El Salvador, translated by Keith Ellis

- IMAGES

- LANGUAGES / LENGUAS

- Amharic

- Anishinaabemowin / Ojibwe

- Arabic

- Bengali (Bangla)

- Cebuano

- Chinese (Mandarin)

- Cree

- Creole / Kréyòl

- Creole: American (Louisiana)

- Czech

- English

- English: Black Canadian / American

- English: Jamaican Patois

- English: Late Mediaeval – Early Renaissance

- English: Middle English

- English: Nineteenth-century Black-American Southern Dialect

- English: Scots

- English: Trinidadian

- Farsi / Persian

- French

- Gaelic: Scottish

- German

- Greek

- Guaraní

- Hebrew

- Hindi

- Huron / Wendat

- Ilocano

- Inuktitut

- Irish

- Italian

- Japanese

- Kalaallisut (Greenlandic)

- Ladino/Judeoespañol

- Maltese

- Maya

- Mi'kmaq / Míkmawísimk

- Náhuatl

- Polish

- Portuguese

- Quechua

- Russian

- Spanish

- Swahili

- Tagalog / Filipino

- Tamil

- Tigrinya

- Turkish

- Tutunakú

- Ukrainian

- Uzbek

- Vietnamese

- Yiddish

- Zapotec

- POETS / POETAS

- A.Z. Foreman

- Abayomi Animashaun

- Abbas Kiarostami

- Abdul Wahhab Al-Bayati

- Abdulhosayn Nosrat

- Abubakar Othman

- Adam Zemans

- Adriana Ierodiakonou

- Agostinho Neto

- Ai Qing

- Ailbhe Ní Ghearbhuigh

- Aimé Césaire

- Akiko Yosano

- Al Young

- Al-Ma'arri

- Alain Mabanckou

- Alan Clark

- Alberto Laucirica

- Alberto Rocasolano

- Albis Torres

- Alcides Iznaga

- Alejandro del Bosque

- Alejandro Fonseca

- Alexander Barclay

- Alexander Best

- Alfonsina Storni

- Alfonso Hernández

- Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson

- Alice Walker

- Alicia Claudia González Maveroff

- Allen Ginsberg

- Alootook Ipellie

- Amelia del Castillo

- Amiri Baraka

- Amy Lowell

- Ana Castillo

- Ana María Caballero

- Andy Quan

- Ann-Marie Scarlett

- Anna Akhmatova

- Anna Marie Sewell

- Anne Carson

- Anne Spencer

- Annie Finch

- António Botto

- Antonio Acosta

- Antonio García

- Aqqaluk Lynge

- Ariruma Kowii

- Armand Garnet Ruffo

- Arna Bontemps

- Arthur Stringer

- Ataulfo Alves

- Athina Papadaki

- Audre Lorde

- Augusto de Campos

- Augusto dos Anjos

- Badr Shakir al-Sayyab

- Bashō

- Bavan Sribalan

- Belkis Cuza Malé

- bell hooks

- Ben the Dancer

- Benito de Jesús

- Berta G. Montalvo

- Bessie Smith

- Beverley Nambozo

- Bienvenido C. Gonzalez

- Blanca Varela

- Bob Kaufman

- Bob Marley

- Boris Pasternak

- Boris Vian

- Briceida Cuevas Cob

- Buffy Sainte-Marie

- Buson

- Caitríona Ní Chléirchín

- Carl Phillips

- Carl Sandburg

- Carlos Aragón

- Carlos Drummond de Andrade

- Carlos Reviejo

- Castro Alves

- Cathal Ó Searcaigh

- César Vallejo

- Chinua Achebe

- Clarence Major

- Claribel Alegría

- Claude McKay

- Claudia Lars

- Cloe Kutsubeli

- Clovis S. Palmer

- Colin Robinson

- Cornelius Eady

- Countee Cullen

- Cynthia Dewi Oka

- Czeslaw Milosz

- D.H. Lawrence

- Daisy Zamora

- Damaris Calderón

- Dan Anace

- Dan Eggs

- Daniel Chirom

- Danielle Boodoo-Fortune

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti

- Dany Laferrière

- David Blackman

- David Rudder

- Delfín Prats

- Delores Gauntlett

- Denise Levertov

- Derek Walcott

- Dino Campana

- Dionne Brand

- Djavan

- Dolores Kendrick

- Don Charles

- Donald Hall

- Dorothy Parker

- Doyali Farah Islam

- Dunya Mikhail

- Dylan Thomas

- E.E. Cummings

- Earl McKenzie

- Eavan Boland

- Edna St.Vincent Millay

- Eduardo Urueta

- Eduardo White

- Edwin A. Lozada

- Edwin Morgan

- Eftychia Panayiotou

- Egon Schiele

- Eileen R. Tabios

- Elena Tamargo

- Eleni Vakalo

- Eliseo Diego

- Elizabeth Bishop

- Ella Wheeler Wilcox

- Elsa Burgos Alonso

- Elyas Mulu Kiros

- Emanyel Ejen

- Emily Dickinson

- Emmanuel W. Védrine

- Encarnación de Armas

- Eric Merton Roach

- Erica Jong

- Ernesto Cardenal

- Erse Soteropoulou

- Essex Hemphill

- Esther Phillips

- Etheridge Knight

- Etta James

- Eugenio Florit

- Ewi Adebayo Faleti

- Eyda T. Machín

- Fayad Jamís

- Federico García Lorca

- Fehmida Riaz

- Feliciano Acosta Alcaraz

- Fereshteh Sari

- Fernando Brant

- Fina García Marruz

- Frances Bellerby

- Frances-Marie Coke

- Frank Marshall Davis

- Frederick Ward

- Freedom Nyamubaya

- Friedrich von Schiller

- G. K. Chesterton

- Gabriel Bamgbose

- Gabriel Okara

- George Elliott Clarke

- George Herbert

- Georgia Douglas Johnson

- Georgina Herrera

- Gerald Kithinji

- Gerardo Can Pat

- Gilles Vigneault

- Giuseppe Ungaretti

- Gladys Waterberg

- Gloria Oden

- Goran Simić

- Grace Paley

- Gregório de Matos

- Gregory Porter

- Guido Guinizelli

- Gwendolyn Bennett

- Gwendolyn Brooks

- Gwendolyn MacEwen

- H. Francisco V. Peñones

- Hafiz

- Halima Xudoyberdiyeva

- Hamid Sabzvâri

- Hari Malagayo Alluri

- Harry Blackbird

- Héctor Pedro Blomberg

- Hector Poullet

- Helene Johnson

- Hellen Chinchilla

- Helon Habila

- Henri Cole

- Henri Nouwen

- Henrietta Ray

- Herminia D. Ibaceta

- Hiroshi Kashiwagi

- Hugo Lindo

- Huseng Batute (José Corazón de Jesús)

- Hushang Hekmati (Sarvi)

- Ian Williams

- Ikkyū

- Inuo Taguchi

- Irene Rutherford McLeod

- Ishmael Reed

- Ishrat Qahramân

- Issa

- Ivan Malkovych

- Izet Sarajlić

- Jacob Nibenegenesabe

- Jaime Sabines

- Jair Córtes

- Jakuren

- Jalâl Behizâd

- James Baldwin

- James Morris

- James Noël

- James Terry White

- James Weldon Johnson

- Jane Kenyon

- Javier Álvarez

- Jay Bernard

- Jayne Cortez

- Júlio Castañon Guimarães

- Jean de Brébeuf

- Jean Nordhaus

- Jee Leong Koh

- Jefferson Bethke

- Jennifer Rahim

- Jenny Mastoraki

- Jessie Redmon Fauset

- Jo Westren

- Joanna Shawana

- Joe Brainard

- Joelle Constant

- Jofre Rocha

- John Ashbery

- John Clare

- John Lennon

- John McCrae

- John Pepper Bekederemo Clark

- John Updike

- Jon Pineda

- Jorge Ben Jor

- Jorge Cantu de la Garza

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Jorge Teillier

- Jorge Valdés Díaz-Vélez

- José Craveirinha

- José David Berríos

- José López Vásquez

- José Luis Valle

- José Luis Villatoro

- José María Cuéllar

- José Pablo Sibaja Campos

- José Valdez

- Josefina Beverido de Risso

- Joseph Brodsky

- Joseph Jarman

- Joseph Ross

- Josephine Heard

- Joy Kogawa

- Joyce Kilmer

- Joyce Wakefield

- Juan Alberto Garay Moisa

- Juan de Dios Peza

- Juan Felipe Herrera

- Juan Hernández Ramírez

- Juan Wallparrimachi

- Juana Inés de la Cruz

- Juana Rosa Pita

- Judith Kroll

- Juliane Okot Bitek

- Jun Tiburcio

- June Jordan

- Kabir

- Kamau Brathwaite

- Kaneko Misuzu

- Karla Báez

- Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm

- Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke

- Kendel Hippolyte

- Kenn Nesbitt

- Kettly Mars

- Kiki Dimoula

- Kleopatra Lymperis

- Kofi Awoonor

- Konstantin Kavafis

- Kusi Paukar

- Kyoshi

- Laboni Islam

- Lalita Curbelo Barberán

- Lamont B. Steptoe

- Langston Hughes

- Lawrence William O'Connor

- Léopold Sédar Senghor

- Lee Maracle

- Lelawattee Manoo-Rahming

- Lenore Kandel

- Lenrie Peters

- Lewis Carroll

- Lewis MacKinnon

- Lil Milagro Ramírez

- Lily Flores Palomino / K'ancharina

- Linda Pastan

- Lorine Niedecker

- Lorna Goodison

- Louis Riel

- Louise Bennett-Coverley

- Louise Glück

- Lourdes Casal

- Luca

- Luci Shaw

- Lucille Clifton

- Luis Mario

- Luis Rogelio Nogueras

- Luis Ronald Calderón Sánchez

- Lupicínio Rodrigues

- M. NourbeSe Philip

- Macuilxochitzin

- Magaly Sánchez

- Mahmoud Darwish

- Manuel Bandeira

- Manuel Villanueva Martínez

- Mao Zedong

- María Elena Walsh

- Marcus Bruce Christian

- Marcus Garvey

- Margaret Atwood

- Margaret D. Gill

- Margaret Sam-Cromarty

- Marge Piercy

- Marilyn Dumont

- Mario Meléndez

- Marta Padilla

- Martin Wylde Carter

- Martinho de Vila

- Mary Elizabeth Coleridge

- Mary Oliver

- Matilde Elena López

- Matthieu Gosztola

- Maurice Kenny

- Maxine Kumin

- Maxwell Bodenheim

- Maya Angelou

- Mayda Pérez Gallego

- Meena Kandaswamy

- Meg Bateman

- Melissanthi

- Melvin Dixon

- Mercedes Durand

- Mervyn Morris

- Mervyn Taylor

- Michael Chitwood

- Michèle Voltaire Marcelin

- Miguel Barnet

- Miguel Hernandez Gilabert

- Mike Finley

- Mildred Barya

- Milton Acorn

- Mina Loy

- Minerva Salado

- Mohammad Mehdi Fulâdvand

- Mohammad-Taqi Bahar

- Molly Peacock

- Mona Zote

- Mosha Folger

- Moyra Donaldson

- Muharrem Aşan

- Murielle Jassinthe

- Nancy Cárdenas

- Nancy Morejón

- Naomi McIlwraith

- Nasrin Behjati

- Nasrin Ranjbar Irani

- Natalio Hernández

- Natasha Trethewey

- Navia Magloire

- Nawal Naffaa

- Neal McLeod

- Nelson Brizuela

- Nezahualcóyotl

- Nguyen Ba Chung

- Nguyen Quang Thieu

- Nicholas Laughlin

- Nicolás Guillén

- Nicomedes Santa Cruz

- Nigel Darbasie

- Nike Adesuyi

- Nikki Giovanni

- Niyi Osundare

- Noel Rosa

- Norma Dunning

- Norman Jordan

- Nurun Nahar

- Nuvia Estévez Machado

- Octavio Paz

- Odette Alonso

- Okot p’Bitek

- Olga García Echeverría

- Oliver Herford

- Omar Khayyám

- Onookme Okome

- Onuora Ossie Enekwe

- Osip Mandelstam

- Pat Lowther

- Pat Parker

- Patrick Rosal

- Paul Hartal

- Paul Laurence Dunbar

- Paula Tavares

- Pauline Johnson

- Pavlina Pampoudi

- Pedro Serrano

- Pegah Ahmadi

- PierPaolo Pasolini

- Qiu Jin

- R.L.C. McFarlane

- Raúl García-Huerta

- Rabindranath Tagore

- Rafaela Chacón Nardi

- Rainer Maria Rilke

- Ralph Carmichael

- Raymond Carver

- Regina Eziagulu Obakhena

- Reginald Shepherd

- Reinaldo Arenas

- Renael González

- Rhea Galanaki

- Rhodora V. Peñaranda

- Richard La Fortune / Anguksuar

- Richard O. Moore

- Richard Wright

- Rin Ishigaki

- Rita Bouma-Pappa

- Rita Bouvier

- Rita Dove

- Rita Joe

- Robert Browning

- Robert Burns

- Robert Creeley

- Robert Frost

- Robert Gurney

- Robert Hayden

- Robert Herrick

- Robert Leighton

- Robert Louis Stevenson

- Roberto Armijo

- Roberto Quesada

- Roberto Sosa

- Rody Gorman

- Roger Robinson

- Rogr Lee

- Rosamaría Roffiel

- Rosario Castellanos

- Rowland Jide Macaulay

- Rubén Darío

- Rui de Noronha

- Rui Nogar

- Ruth Ellen Kocher

- Sadako Kurihara

- Saeed Jones

- Saghir Isfahâni

- Saint Dallán Forgaill

- Samuel Selvon

- Sara Teasdale

- Seamus Heaney

- Sebastian Brant

- Serafín Quiteño

- Sharon Olds

- Siegfried Sassoon

- Soleída Ríos

- Sonia Civallero

- Sorley Maclean

- Sterling A. Brown

- Steve Langley

- Steve Turner

- Sunday Ayewanu

- Susan Kiguli

- Susana Reyes

- Sylvana Salmanpour

- Sylvia Plath

- T. S. Eliot

- Tanya Shirley

- Tares Oburumu

- Tasoula Karageorgiou

- Ted Joans

- Teresita Fernández

- Thich Nhat Hanh

- Thomas Moore

- Tom Wayman

- Tony Kan

- Tricia Postle

- Una Marson

- Vahni Capildeo

- Valdeck Almeida de Jesus

- Véronique Tadjo

- Victor P. Gendrano

- Victor Terán

- Vinícius de Moraes

- Virgilio Piñera

- Walt Whitman

- Wayne Keon

- William Blake

- William Butler Yeats

- William J. Harris

- William Matthews

- William Shakespeare

- Wilson Batista

- Winston Anthony Bailey

- Xorge M. González

- Yehuda Amichai

- Yolanda Ulloa

- Yosano Hiroshi

- Yusef Komunyakaa

- Zoe Karelli

- Uncategorized

Mid Mo Design.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

%d