Sterling Allen Brown: “She jes’ gits hold of us dataway”

Posted: February 11, 2014 Filed under: English: Nineteenth-century Black-American Southern Dialect, Sterling A. Brown | Tags: Black History Month, Ma Rainey Comments Off on Sterling Allen Brown: “She jes’ gits hold of us dataway”

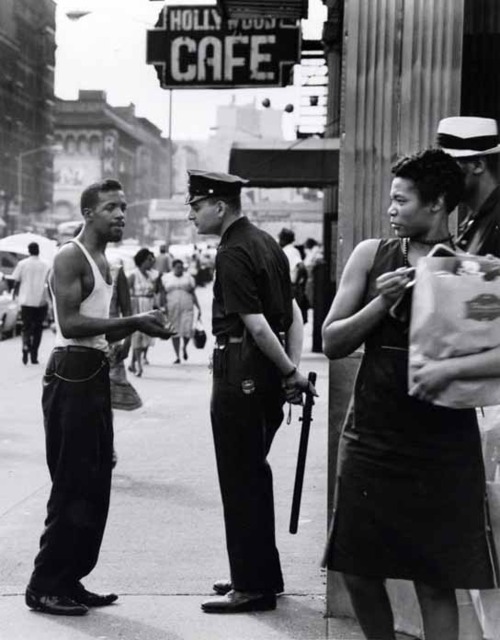

The family pictured here was part of The Great Migration: African-Americans on the move from the rural South up or over to towns and cities of the North and MidWest. They wished to escape that Life of which Ma Rainey sang…

Sterling Allen Brown (1901-1989)

“Ma Rainey” (1932)

.

I

When Ma Rainey

Comes to town,

Folks from anyplace

Miles aroun’,

From Cape Girardeau,

Poplar Bluff,

Flocks in to hear

Ma do her stuff;

Comes flivverin’ in,

Or ridin’ mules,

Or packed in trains,

Picknickin’ fools. . . .

That’s what it’s like,

Fo’ miles on down,

To New Orleans delta

An’ Mobile town,

When Ma hits

Anywheres aroun’.

.

II

Dey comes to hear Ma Rainey from de little river settlements,

From blackbottorn cornrows and from lumber camps;

Dey stumble in de hall, jes a-laughin’ an’ a-cacklin’,

Cheerin’ lak roarin’ water, lak wind in river swamps.

An’ some jokers keeps deir laughs a-goin’ in de crowded aisles,

An’ some folks sits dere waitin’ wid deir aches an’ miseries,

Till Ma comes out before dem, a-smilin’ gold-toofed smiles

An’ Long Boy ripples minors on de black an’ yellow keys.

.

III

O Ma Rainey,

Sing yo’ song;

Now you’s back

Whah you belong,

Git way inside us,

Keep us strong. . . .

O Ma Rainey,

Li’l an’ low;

Sing us ’bout de hard luck

Roun’ our do’;

Sing us ’bout de lonesome road

We mus’ go. . .

.

IV

I talked to a fellow, an’ the fellow say,

“She jes’ catch hold of us, somekindaway.

She sang Backwater Blues one day:

‘It rained fo’ days an’ de skies was dark as night,

Trouble taken place in de lowlands at night.

‘Thundered an’ lightened an’ the storm begin to roll

Thousan’s of people ain’t got no place to go.

‘Den I went an’ stood upon some high ol’ lonesome hill,

An’ looked down on the place where I used to live.’

An’ den de folks, dey natchally bowed dey heads an’ cried,

Bowed dey heavy heads, shet dey moufs up tight an’ cried,

An’ Ma lef’ de stage, an’ followed some de folks outside.”

Dere wasn’t much more de fellow say:

She jes’ gits hold of us dataway.

. . .

“Ma Rainey” from The Collected Poems of Sterling A. Brown, edited by Sterling A. Brown. © 1932

Ma Rainey with her band in 1923_Eddie Pollack_Albert Wynn_Thomas A. Dorsey_Dave Nelson_Gabriel Washington

. . . . .

“Lift Every Voice and Sing” & Augusta Savage’s “The Harp”

Posted: February 10, 2014 Filed under: English, James Weldon Johnson | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on “Lift Every Voice and Sing” & Augusta Savage’s “The Harp”“Lift Every Voice and Sing” is a song first written as a poem in 1899 by James Weldon Johnson (1871-1938). It was Weldon’s brother John Rosamond Johnson who set the poem to music. The poem was first spoken aloud by several hundred schoolchildren on February 12th, 1900, at the segregated Stanton School in Jacksonville, Florida, where James Johnson was principal. The recital of the new poem was meant to honour both visiting guest Booker T. Washington – and Abraham Lincoln, whose birth date fell on the same day.

. . .

Lift every voice and sing, till earth and heaven ring,

Ring with the harmonies of liberty;

Let our rejoicing rise, high as the listening skies,

Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

.

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us;

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

Let us march on till victory is won.

.

Stony the road we trod, bitter the chastening rod,

Felt in the days when hope unborn had died;

Yet with a steady beat, have not our weary feet

Come to the place for which our fathers sighed?

.

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered,

We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered;

Out from the gloomy past, till now we stand at last

Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.

.

God of our weary years, God of our silent tears,

Thou Who hast brought us thus far on the way;

Thou Who hast by Thy might, led us into The Light,

Keep us forever in the path, we pray.

.

Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we met Thee;

Lest our hearts, drunk with the wine of the world, forget Thee;

Shadowed beneath Thy hand, may we forever stand,

True to our God, true to our native land.

. . .

Augusta Savage (1892-1962), a Florida sculptor (born near Jacksonville) who grew artistically / worked in New York City during The Harlem Renaissance, was commissioned in 1939 to do a monumental plaster work for the New York World’s Fair. “The Harp” was strongly influenced by James Weldon Johnson’s poem “Lift Every Voice and Sing”. The 16-foot tall piece was exhibited outside the Contemporary Arts building where it received much acclaim. The sculpture depicted twelve stylized Black singers of graduated heights that symbolized the strings of the harp. The sounding board was formed by the hand and arm of God, and a kneeling man holding music represented the foot pedal. No funds were made available to cast “The Harp” in permanent bronze, nor were there any facilities to store it. After the World’s Fair was over, “The Harp” was demolished, like most of the event’s art.

. . . . .

“Make sparks”: an inspirational poem

Posted: February 4, 2014 Filed under: Alexander Best, English | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on “Make sparks”: an inspirational poem“Make sparks”: an inspirational poem

.

Best, Carrie;

Desmond, Viola;

Rosa Parks.

Two at The Movies;

One on The Bus;

Three for Justice.

.

Step upon step,

Day after day,

Choice by choice.

And what if You,

And what if I,

Lend our voices,

Look Wrong in its eye?

.

It’s hard to have guts

Yet do it we must

– no ifs, ands, or buts –

Cry “Freedom!” and Aye –

Trust in Our Common Future.

. . .

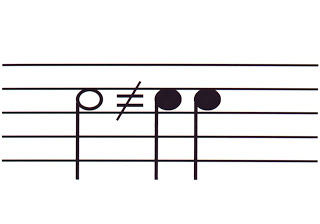

The illustration at the top is called “Poesía visual para Rosa Parks” by Rodrigo Alvarez. Alvarez uses musical symbols in ironic fashion. His equation means: one white half note does not equal two black quarter notes. Yet in musical notation half notes are white, and they do equal two black quarter notes. Alvarez has created a confusing “non-equation” to draw attention to untenable notions of racial segregation and inequality.

. . . . .

Henrietta Cordelia Ray: Odes to Toussaint L’Ouverture and Paul Laurence Dunbar

Posted: February 1, 2014 Filed under: English, Henrietta Ray | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Henrietta Cordelia Ray: Odes to Toussaint L’Ouverture and Paul Laurence DunbarHenrietta Cordelia Ray (1852?-1916)

“Toussaint L’Ouverture”

(from: Champions of Freedom, published 1910)

.

To those fair isles where crimson sunsets burn,

We send a backward glance to gaze on thee,

Brave Toussaint! thou wast surely born to be

A hero; thy proud spirit could but spurn

Each outrage on thy race. Couldst thou unlearn

The lessons taught by instinct? Nay! and we

Who share the zeal that would make all men free,

Must e’en with pride unto thy life-work turn.

Soul-dignity was thine and purest aim;

And ah! how sad that thou wast left to mourn

In chains ‘neath alien skies. On him, shame! shame!

That mighty conqueror who dared to claim

The right to bind thee. Him we heap with scorn,

And noble patriot! guard with love thy name.

.

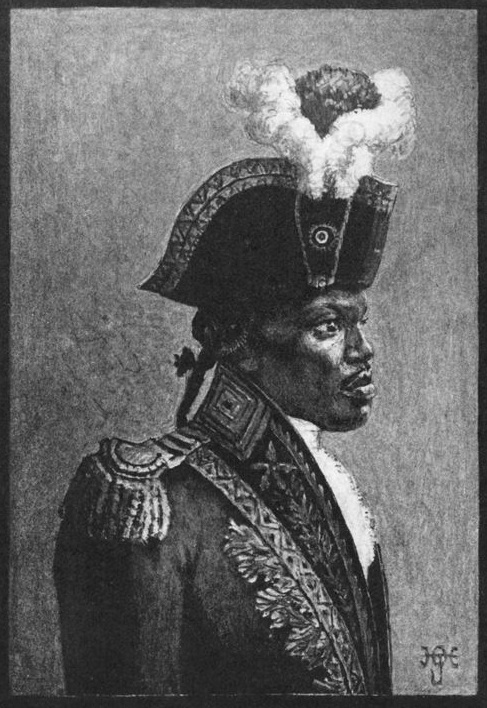

Toussaint L’Ouverture (1743-1803): Leader of the Haitian Revolution for Independence

. . .

Two Quatrains:

“Ambition”

.

What is ambition? ’tis unrest, defeat!

A goad, a spur, a Quick’ning the heart’s beat;

A fevered pulse, a grasp at shadows fleet,

A beck’ning vision, fair, illusive, sweet!

.

“Instability”

.

What we to-day prize and most fondly cherish,

To-morrow scarce may claim a moment’s reck’ning.

Yet why adjust the cause? Let doubt all perish.

Can argument withstand the spirit’s beck’ning?

“In Memoriam: Paul Laurence Dunbar”

.

The Muse of Poetry came down one day,

And brought with willing hands a rare, sweet gift;

She lingered near the cradle of a child,

Who first unto the sun his eyes did lift.

She touched his lips with true Olympian fire,

And at her bidding Fancies hastened there,

To flutter lovingly around the one

So favored by the Muse’s gentle care.

.

Who was this child? The offspring of a race

That erst had toiled ‘neath slavery’s galling chains.

And soon he woke to utterance and sang

In sweetly cadenced and in stirring strains,

Of simple joys, and yearnings, and regrets;

Anon to loftier themes he turned his pen;

For so in tender, sympathetic mood

He caught the follies and the griefs of men.

.

His tones were various: we list, and lo!

“Malindy Sings,” and as the echoes die,

The keynote changes and another strain

Of solemn majesty goes floating by;

And sometimes in the beauty and the grace

Of an impassioned, melancholy lay,

We seem to hear the surge, and swell, and moan

Of soft orchestral music far away.

.

Paul Dunbar dead! His genius cannot die!

It lives in songs that thrill, and glow, and soar;

Their pathos and their joy will fill our hearts,

And charm and satisfy e’en as of yore.

So when we would lament our poet gone,

With sorrow that his lyre is resting now,

Let us remember, with the fondest pride,

That Fame’s immortal wreath has crowned his brow.

.

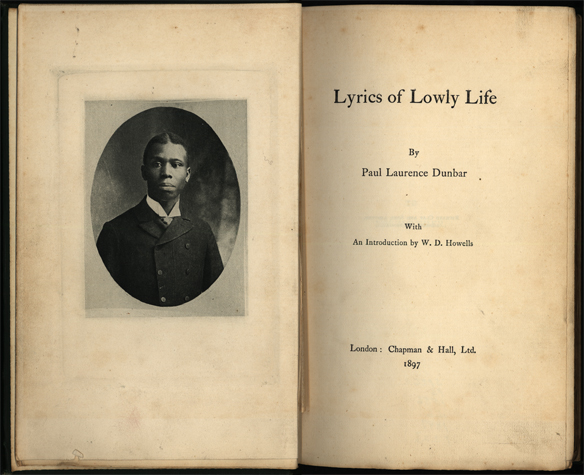

Paul (Laurence) Dunbar (1872-1906): Black-American poet and playwright from Dayton, Ohio

. . .

To read poems by Paul Laurence Dunbar click on the following link:

“Go on and up!”: the tight-rope-walking poetry of Paul Laurence Dunbar

. . .

Source for the above poems: the online archives of The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture (Harlem, New York City)

. . . . .

Josephine Heard: “The Advance of Education”

Posted: February 1, 2014 Filed under: English, Josephine Heard | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Josephine Heard: “The Advance of Education”Josephine Delphine Henderson Heard (1861-1921)

“The Advance of Education”

.

What means this host advancing,

With such melodious strain:

These men on steeds a prancing,

This mighty marshaled train.

.

They come while drum and fife resound,

And steeds with foam aflecked,

Whose restless feet do spurn the ground,

Their riders gaily decked.

.

With banners proudly waving,

Fearless in Freedom’s land,

All opposition braving,

With courage bold they stand.

.

Come join the raging battle,

Come join the glorious fray;

Come spite of bullets’ rattle,

This is enlistment day.

.

Hark ! hear the Proclamation

Extend o’er all the land;

Come every Tribe and Nation

Join education’s band.

.

Now the command is given–

Strike ! strike grim ignorance low;

Strike till her power is given;

Strike a decisive blow.

. . .

“Sunshine after Cloud”

.

Come, “Will,” let’s be good friends again,

Our wrongs let’s be forgetting,

For words bring only useless pain,

So wherefore then be fretting.

.

Let’s lay aside imagined wrongs,

And ne’er give way to grieving,

Life should be filled with joyous songs,

No time left for deceiving.

.

I’ll try and not give way to wrath,

Nor be so often crying;

There must some thorns be in our path,

Let’s move them now by trying.

.

How, like a foolish pair were we,

To fume about a letter;

Time is so precious, you and me;

Must spend ours doing better.

“Judge Not”

.

Perchance, the friend who cheered thy early years,

Has yielded to the tempter’s power;

Yet, why shrink back and draw away thy skirt,

As though her very touch would do thee hurt?

Wilt thou prove stronger in temptation’s hour?

.

Perchance, the one thou trusteth more than life,

Has broken love’s most sacred vow;

Yet judge him not–the victor in life’s strife,

Is he who beareth best the burden of life,

And leaveth God to judge, nor questions how.

.

Sing the great song of love to all, and not

The wailing anthems of thy woes;

So live thy life that thou may’st never feel

Afraid to say, as at His throne you kneel,

“Forgive me God, as I forgive my foes!”

. . .

Source for the above poems: the online archives of The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture (Harlem, New York City)

.

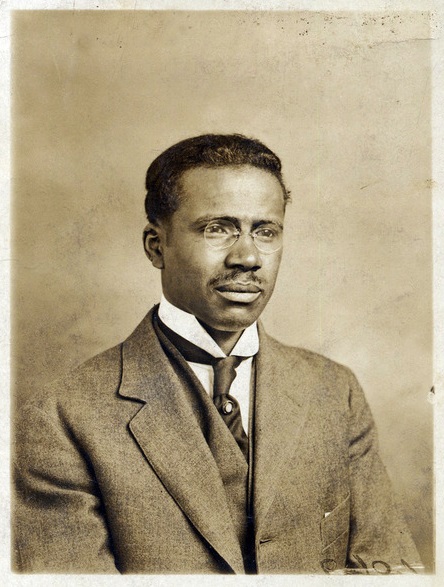

Photographs: An unknown Beauty in her finery, perhaps around 1910? / A portrait of, possibly, one Clifford L. Miller, first decade of the 20th century?

. . . . .

Gwendolyn Brooks: “Mis sueños, mis trabajos, tendrán que esperar hasta mi vuelta del infierno”

Posted: January 30, 2014 Filed under: English, Gwendolyn Brooks, Gwendolyn Brooks: poemas traducidos, Spanish Comments Off on Gwendolyn Brooks: “Mis sueños, mis trabajos, tendrán que esperar hasta mi vuelta del infierno”“La balada-soneto”

.

Oh madre, madre, ¿dónde está la felicidad?

Se llevaron a mi alto amante a la guerra.

Me dejaron lamentándome. No puedo saber

de qué me sirve la taza vacía del corazón.

Él no va a volver nunca más. Algún día

la guerra va a terminar pero, oh, yo supe

cuando salió, grandioso, por esa puerta,

que mi dulce amor tendría que serme infiel.

Que tendría que serme infiel. Tendría que cortejar

a la coqueta Muerte, cuyos imprudentes, extraños

y posesivos brazos y belleza (de cierta clase)

pueden hacer que un hombre duro dude –

y cambie. Y que sea el que tartamudee: Sí.

Oh madre, madre, ¿dónde está la felicidad?

.

(1949)

.

Versión de Tom Maver

. . .

“Mis sueños, mis trabajos,

tendrán que esperar hasta

mi vuelta del infierno”

.

Almaceno mi miel y mi pan tierno

en jarras y cajones protegidos

recomiendo a las tapas y pestillos

resistir hasta mi vuelta del infierno.

Hambrienta, me siento como incompleta

no se si una cena volveré a probar

todos me dicen que debo aguardar

la débil luz. Con mi mirada atenta

espero que al acabar los duros días

al salir a rastras de mi tortura

mi corazón recordará sin duda

cómo llegar hasta la casa mía.

Y mi gusto no será indiferente

a la pureza del pan y de la miel.

.

(1963)

. . .

“El funeral de la prima Vit”

.

Sin protestar es llevada afuera.

Golpea el ataúd que no la aguanta

ni satín ni cerrojos la contentan

ni los párpados contritos que tuviera.

Oh, mucho, es mucho, ahora sabe

ella se levanta al sol, va, camina

regresa a sus lugares y se inclina

en camas y cosas que la gente ve.

Vital y rechinante se endereza

y hasta mueve sus caderas y sisea

derrama mal vino en su chal de seda

habla de embarazos, dice agudezas

feliz, recorre senderos y parques

histérica, loca feliz. Feliz es.

.

(1994)

.

Versiones de Óscar Godoy Barbosa

Gwendolyn Brooks

“The Sonnet-Ballad”

.

Oh mother, mother, where is happiness?

They took my lover’s tallness off to war,

Left me lamenting. Now I cannot guess

What I can use an empty heart-cup for.

He won’t be coming back here any more.

Some day the war will end, but, oh, I knew

When he went walking grandly out that door

That my sweet love would have to be untrue.

Would have to be untrue. Would have to court

Coquettish death, whose impudent and strange

Possessive arms and beauty (of a sort)

Can make a hard man hesitate–and change.

And he will be the one to stammer, “Yes.”

Oh mother, mother, where is happiness?

. . .

“My dreams, my works, must wait till after Hell”

.

I hold my honey and I store my bread

In little jars and cabinets of my will.

I label clearly, and each latch and lid

I bid, Be firm till I return from hell.

I am very hungry. I am incomplete.

And none can tell when I may dine again.

No man can give me any word but Wait,

The puny light. I keep eyes pointed in;

Hoping that, when the devil days of my hurt

Drag out to their last dregs and I resume

On such legs as are left me, in such heart

As I can manage, remember to go home,

My taste will not have turned insensitive

To honey and bread old purity could love.

. . .

“The rites for cousin Vit”

.

Carried her unprotesting out the door.

Kicked back the casket-stand. But it can’t hold her,

That stuff and satin aiming to enfold her,

The lid’s contrition nor the bolts before.

Oh oh. Too much. Too much. Even now, surmise,

She rises in the sunshine. There she goes,

Back to the bars she knew and the repose

In love-rooms and the things in people’s eyes.

Too vital and too squeaking. Must emerge.

Even now she does the snake-hips with a hiss,

Slops the bad wine across her shantung, talks

Of pregnancy, guitars and bridgework, walks

In parks or alleys, comes haply on the verge

Of happiness, haply hysterics. Is.

. . .

Gwendolyn Brooks (Topeka, Kansas, EE.UU.) 1917 – 2000

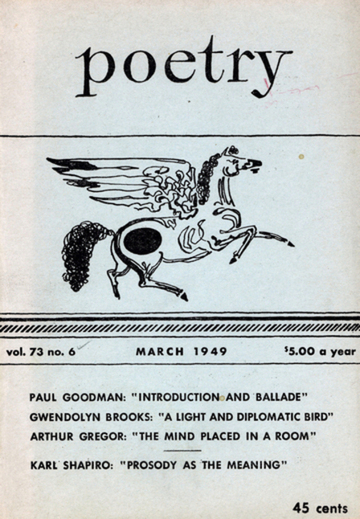

Primera autora negra ganadora del Premio Pulitzer de poesía (1950, Annie Allen). Comprometida con la igualdad y la identidad racial, fue una poeta con conciencia política, dedicada activamente a llevar la poesía a todas las clases sociales, fuera de la academia. Brooks visitaba a Etheridge Knight después de su encarcelación para animarle en su escritura de poesía. Para leer los poemas de Etheridge Knight (en inglés) cliquea el enlace.

.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917 – 2000) was the first Black woman to win The Pulitzer Prize – in 1950 for her poetry collection Annie Allen. Concerned with racial equality and identity, Brooks dedicated herself to bringing poetry to people of all classes – outside of the realm of academe. A woman of political conscience, she would visit the unjustly over-incarcerated Etheridge Knight in jail to encourage him in the flowering of his poetic voice. Click the link below to read his poems.

. . . . .

Dany Laferrière: “Fire is nothing next to Ice…”

Posted: January 29, 2014 Filed under: Dany Laferrière, English, French, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Dany Laferrière: “Fire is nothing next to Ice…”Dany Laferrière (Windsor Klébert Laferrière)

(né 1953, à Petit Goâve, Haïti, vivant à Montréal, Canada)

Extraits de Chronique de la dérive douce / Excerpts from Chronicle of the Sweet Year Adrift (1994):

.

En plein hiver

je rêve à une île dénudée

dans la mer des Caraïbes

avant d’enfouir

ce caillou brûlant

si profondément

dans mon corps

que j’aurai

du mal

à le retrouver.

.

In the midst of winter

I dream of an island bare,

in the Caribbean sea,

before burying this smouldering head

so deep within my body that

I’d be hard put to find it again.

Le feu n’est rien

à côté de la glace

pour brûler un homme

mais pour ceux qui

viennent du sud,

la faim peut mordre

encore plus durement

que le froid.

.

Fire is nothing next to Ice

for burning a man

but for those who come from the south,

Hunger can bite much harder than the cold.

.

Translation from French: Alexander Best

. . .

Dany Laferrière est un écrivain haïtien-canadien qui a reçu le prix Médicis en 2009 pour son roman L’Énigme du Retour. Le Médicis est décerné à un auteur qui n’a pas encore une notoriété correspondant à son talent.

En décembre de 2013 Laferrière est devenu membre de l’Académie française.

.

Dany Laferrière is a Haitian-Canadian writer who received the Médicis Prize in 2009 for his novel The Enigma of Return. The Prix Médicis is given to an author whose fame is not yet as big as his artistry. In December of 2013 Laferrière was elected to the Académie Française, France’s most learnéd body on French linguistic matters.

. . . . .

Norman Jordan: “Como brotar un poema”

Posted: January 28, 2014 Filed under: English, Norman Jordan, POETS / POETAS, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: El Movimiento del Arte Negro – Cleveland en los años 60 y 70 Comments Off on Norman Jordan: “Como brotar un poema”Norman Jordan (nacido en 1938, Virgina del Oeste, EE.UU.)

“El Sacrificio”

.

El precio de leche ha subido de nuevo

y el bebé está bebiendo más…

Carajo, supongo que tendré que

abandonar los cigarillos

– por lo tanto arruinaré mis chances de

agarrar el cáncer.

WTF – no se puede tener todo.

. . .

Norman Jordan (born 1938, West Virginia, USA)

“The Sacrifice”

.

The price of

milk has

gone up again

and the baby

is drinking more.

Hell,

I guess I’ll

have to give up

cigarettes

and blow my

chances

of catching lung

cancer.

What the fuck,

you can’t have

everything.

. . .

“Alimentando a los Leones”

.

Se atreven en nuestro barrio

con el sol

un ejército de trabajadores sociales

llevando sus maletines;

relleno de mentiras y sonrisitas tontas;

distribuyendo cheques de asistencia y vales de despensa;

apurando de un departamento al otro para

llenar su cuota

– y largarse

antes del ocaso.

“Feeding the Lions”

.

They come into

our neighbourhood

with the sun,

an army of

social workers

carrying briefcases,

filled with lies

and stupid grins,

passing out relief

cheques

and food stamps,

hustling from one

apartment to another

so they can fill

their quota

and get back out

before dark.

. . .

“Como brotar un poema”

.

En primer lugar,

pon unas siete cucharadas de palabras

en un frasco galón

.

Cubre las palabras

con ideas líquidas

y déjalas absorber por una noche

.

Por la mañana

vierte las viejas ideas y

enjuaga las palabras con pensamientos frescos

.

Inclina al revés en un rincón el frasco

y déjalo desaguar

.

Sigue con el enjuague, día con día,

hasta que se forma un poema

.

Finalmente,

coloca el poema en el sol

para que pueda agarrar el color de la Vida.

. . .

“How to sprout a poem”

.

First, place

about seven

tablespoons of words

in a gallon jar

.

Cover the words

with liquid ideas

and let soak overnight

.

The following morning,

pour off the old ideas

and rinse

the words with fresh thoughts

Tilt the jar upside down

in a corner

and let it drain

.

Continue rinsing daily

until a poem forms

.

Last, place the poem

in the sunlight

so it can take on

the colour of Life.

. . . . .

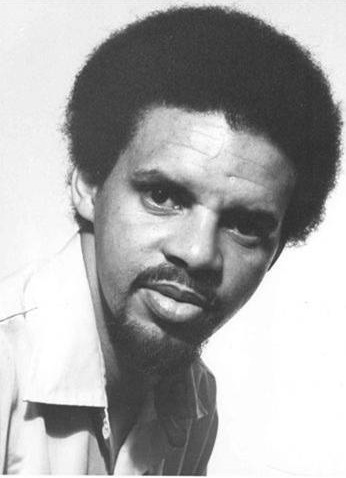

Etheridge Knight: “My Life, the quality of which…”

Posted: January 28, 2014 Filed under: English, Etheridge Knight | Tags: The Black Arts Movement: Indianapolis in the 1960s and 70s Comments Off on Etheridge Knight: “My Life, the quality of which…”Etheridge Knight (Corinth, Mississippi, USA, 1931-1991)

“My Life, the quality of which…”

.

My Life, the quality of which,

from the moment my father grunted and ‘cummed’,

until now, as the sounds of my words

bruised your ears,

is,

and can be felt,

in the one word:

Desperation

– but you have to feel for it.

. . .

“A WASP Woman visits a Black Junkie in Prison”

.

After explanations and regulations, he

Walked warily in.

Black hair covered his chin, subscribing to

Villainous ideal.

“This can not be real,” he thought, “this is a

Classical mistake;

This is a cake baked with embarrassing icing;

Somebody’s got

Likely as not, a big fat tongue in cheek!

What have I to do

With a prim and proper-blooded lady?”

Christ in deed has risen

When a Junkie in prison visits with a WASP woman.

.

“Hold your stupid face, man,

Learn a little grace, man; drop a notch the sacred shield.

She might have good reason,

Like: ‘I was in prison and ye visited me not,’ or—some such.

So sweep clear

Anachronistic fear, fight the fog,

And use no hot words.”

.

After the seating

And the greeting, they fished for a denominator,

Common or uncommon;

And could only summon up the fact that both were human.

“Be at ease, man!

Try to please, man!—the lady is as lost as you:

‘You got children, Ma’am?’” he said aloud.

.

The thrust broke the dam, and their lines wiggled in the water.

She offered no pills

To cure his many ills, no compact sermons, but small

And funny talk:

“My baby began to walk… simply cannot keep his room clean…”

Her chatter sparked no resurrection and truly

No shackles were shaken

But after she had taken her leave, he walked softly,

And for hours used no hot words.

. . .

“A Fable”

.

Once upon a today and yesterday and nevermore there were 7 men and women all locked / up in prison cells. Now these 7 men and women were innocent of any crimes; they were in prison because their skins were black. Day after day, the prisoners paced their cells, pining for their freedom. And the non-black jailers would laugh at the prisoners and beat them with sticks and throw their food on the floor. Finally, prisoner #1 said, “I will educate myself and emulate the non-coloured people. That is the way to freedom—c’mon, you guys, and follow me.” “Hell, no,” said prisoner #2. “The only way to get free is to pray to my God and he will deliver you like he delivered Daniel from the lion’s den, so unite and follow me.” “Bullshit,” said prisoner #3. “The only way / out is thru this tunnel i’ve been quietly digging, so c’mon, and follow me.” “Unh-uh,” said prisoner #4, “that’s too risky. The only right / way is to follow all the rules and don’t make the non-coloured people angry, so c’mon brothers and sisters and unite behind me.” “Fuck you!” said prisoner #5, “The only way / out is to shoot our way out, if all of you get / together behind me.” “No,” said prisoner #6, “all of you are incorrect; you have not analyzed the political situation by my scientific method and historical meemeejeebee. All we have to do is wait long enough and the bars will bend from their own inner rot. That is the only way.” “Are all of you crazy,” cried prisoner #7. “I’ll get out by myself, by ratting on the rest of you to the non-coloured people. That is the way, that is the onlyway!” “No-no,” they all cried, “come and follow me. I have the / way, the only way to freedom.” And so they argued, and to this day they are still arguing; and to this day they are still in their prison cells, their stomachs / trembling with fear.

. . .

“Feeling Fucked Up”

.

Lord she’s gone done left me done packed / up and split

and I with no way to make her

come back and everywhere the world is bare

bright bone white crystal sand glistens

dope death dead dying and jiving drove

her away made her take her laughter and her smiles

and her softness and her midnight sighs—

Fuck Coltrane and music and clouds drifting in the sky

fuck the sea and trees and the sky and birds

and alligators and all the animals that roam the earth

fuck marx and mao fuck fidel and nkrumah and

democracy and communism fuck smack and pot

and red ripe tomatoes fuck joseph fuck mary fuck

god jesus and all the disciples fuck fanon nixon

and malcolm fuck the revolution fuck freedom fuck

the whole muthafucking thing

all i want now is my woman back

so my soul can sing.

Etheridge Knight was many things during his life: one of seven children whose family went from Mississippi to Kentucky to Indianapolis; shoe-shine boy; poolhall habitué; medic during the Korean War; heroin addict; ex-temporaneous “toaster”; purse snatcher + 8-year prison inmate; a serious and dedicated poet. His poetry volumes included Poems from Prison (1968) and Belly Songs and Other Poems (1973).

. . . . .