Langston Hughes: “Montage of a Dream Deferred”

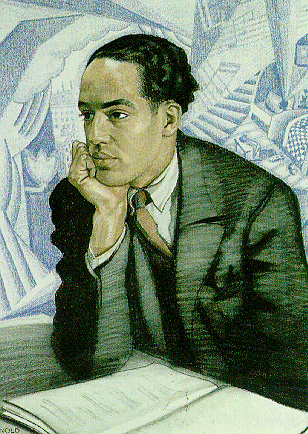

Posted: February 1, 2013 Filed under: English, English: Black Canadian / American, Langston Hughes | Tags: Black History Month poems Comments Off on Langston Hughes: “Montage of a Dream Deferred”Langston Hughes (born February 1st 1902, died 1967)

“Montage of a Dream Deferred” (1951): a selection of poems

.

“Children’s Rhymes”

.

When I was a chile we used to play,

“One – two – buckle my shoe!”

and things like that. But now, Lord,

listen at them little varmints!

.

By what sends

the white kids

I ain’t sent:

I know I can’t

be President.

.

There is two thousand children

In this block, I do believe!

.

What don’t bug

them white kids

sure bugs me:

We knows everybody

ain’t free!

.

Some of these young ones is cert’ly bad –

One batted a hard ball right through my window

And my gold fish et the glass.

.

What’s written down

for white folks

ain’t for us a-tall:

“Liberty And Justice –

Huh – For All.”

.

Oop-pop-a-da!

Skee! Daddle-de-do!

Be-bop!

.

Salt’ peanuts!

.

De-dop!

. . .

“Necessity”

.

Work?

I don’t have to work.

I don’t have to do nothing

but eat, drink, stay black, and die.

This little old furnished room’s

so small I can’t whip a cat

without getting fur in my mouth

and my landlady’s so old

her features is all run together

and God knows she sure can overcharge –

which is why I reckon I does

have to work after all.

. . .

“Question (2)”

.

Said the lady, Can you do

what my other man can’t do –

that is

love me, daddy –

and feed me, too?

.

Figurine

.

De-dop!

. . .

“Easy Boogie”

.

Down in the bass

That steady beat

Walking walking walking

Like marching feet.

.

Down in the bass

That easy roll,

Rolling like I like it

In my soul.

.

Riffs, smears, breaks.

.

Hey, Lawdy, Mama!

Do you hear what I said?

Easy like I rock it

In my bed!

. . .

“What? So Soon!”

.

I believe my old lady’s

pregnant again!

Fate must have

some kind of trickeration

to populate the

cllud nation!

Comment against Lamp Post

You call it fate?

Figurette

De-daddle-dy!

De-dop!

. . .

“Tomorrow”

.

Tomorrow may be

a thousand years off:

TWO DIMES AND A NICKEL ONLY

Says this particular

cigarette machine.

.

Others take a quarter straight.

.

Some dawns

wait.

. . .

“Café: 3 a.m.”

.

Detectives from the vice squad

with weary sadistic eyes

spotting fairies.

Degenerates,

some folks say.

.

But God, Nature,

or somebody

made them that way.

Police lady or Lesbian

over there?

Where?

. . .

“125th Street”

.

Face like a chocolate bar

full of nuts and sweet.

.

Face like a jack-o’-lantern,

candle inside.

.

Face like a slice of melon,

grin that wide.

. . .

“Up-Beat”

.

In the gutter

boys who try

might meet girls

on the fly

as out of the gutter

girls who will

may meet boys

copping a thrill

while from the gutter

both can rise:

But it requires

Plenty eyes.

“Mystery”

.

When a chile gets to be thirteen

and ain’t seen Christ yet,

she needs to set on de moaner’s bench

night and day.

.

Jesus, lover of my soul!

.

Hail, Mary, mother of God!

.

Let me to thy bosom fly!

.

Amen! Hallelujah!

.

Swing low, sweet chariot,

Coming for to carry me home.

.

Sunday morning where the rhythm flows,

How old nobody knows –

yet old as mystery,

older than creed,

basic and wondering

and lost as my need.

.

Eli, eli!

Te deum!

Mahomet!

Christ!

.

Father Bishop, Effendi, Mother Horne,

Father Divine, a Rabbi black

as black was born,

a jack-leg preacher, a Ph.D.

.

The mystery

and the darkness

and the song

and me.

. . .

“Nightmare Boogie”

.

I had a dream

and I could see

a million faces

black as me!

A nightmare dream:

Quicker than light

All them faces

Turned dead white!

Boogie-woogie,

Rolling bass,

Whirling treble

Of cat-gut lace.

. . .

“Blues at Dawn”

.

I don’t dare start thinking in the morning.

I don’t dare start thinking in the morning.

If I thought thoughts in bed,

Them thoughts would bust my head –

So I don’t dare start thinking in the morning.

.

I don’t dare remember in the morning

Don’t dare remember in the morning.

If I recall the day before,

I wouldn’t get up no more –

So I don’t dare remember in the morning.

. . .

“Neighbour”

.

Down home

he sets on a stoop

and watches the sun go by.

In Harlem

when his work is done

he sets in a bar with a beer.

He looks taller than he is

and younger than he ain’t.

He looks darker than he is, too.

And he’s smarter than he looks,

He ain’t smart.

That cat’s a fool.

Naw, he ain’t neither.

He’s a good man,

except that he talks too much.

In fact, he’s a great cat.

But when he drinks,

he drinks fast.

Sometimes

he don’t drink.

True,

he just

lets his glass

set there.

. . .

“Subway Rush Hour”

.

Mingled

breath and smell

so close

mingled

black and white

so near

no room for fear.

. . .

“Brothers”

.

We’re related – you and I,

You from the West Indies,

I from Kentucky.

.

Kinsmen – you and I,

You from Africa,

I from U.S.A.

.

Brothers – you and I.

. . .

“Sliver”

.

Cheap little rhymes

A cheap little tune

Are sometimes as dangerous

As a sliver of the moon.

A cheap little tune

To cheap little rhymes

Can cut a man’s

Throat sometimes.

. . .

“Hope (2)”

.

He rose up on his dying bed

and asked for fish.

His wife looked it up in her dream book

and played it.

. . .

“Harlem (2)”

.

What happens to a dream deferred?

.

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore –

and then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over –

like a syrupy sweet?

.

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

.

Or does it explode?

. . .

“Letter”

.

Dear Mama,

Time I pay rent and get my food

and laundry I don’t have much left

but here is five dollars for you

to show you I still appreciates you.

My girl-friend send her love and say

she hopes to lay eyes on you sometime in life.

Mama, it has been raining cats and dogs up

here. Well, that is all so I will close.

You son baby

Respectably as ever,

Joe

. . .

“Motto”

.

I play it cool

And dig all jive.

That’s the reason

I stay alive.

.

My motto,

As I live and learn,

Is:

Dig And Be Dug

In Return.

. . . . .

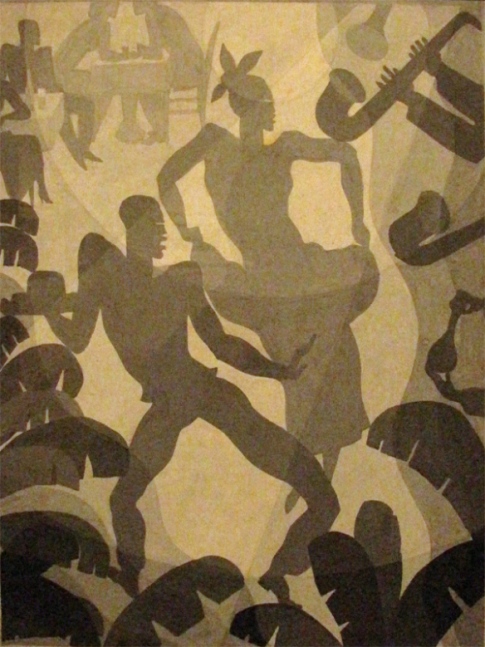

From Hughes’ introduction to his 1951 collection “Montage of a Dream Deferred”:

“In terms of current Afro-American popular music and the sources from which it has progressed – jazz, ragtime, swing, blues, boogie-woogie, and be-bop – this poem on contemporary Harlem, like be-bop, is marked by conflicting changes, sudden nuances, sharp and impudent interjections, broken rhythms, and passages sometimes in the manner of the jam session, sometimes the popular song, punctuated by the riffs, runs, breaks, and distortions of the music of a community in transition.”

Editor’s note:

Langston Hughes’ poems “Theme for English B” and “Advice” – both of which were included in his publication of “Montage of a Dream Deferred” – are featured in separate Hughes’ posts on Zócalo Poets.

. . . . .

“Montage of a Dream Deferred”- from The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes, edited by Arnold Rampersad, with David Roessel, 1994

All poems © The Estate of Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes: “Tarea para el segundo curso de inglés” / “Theme for English B”, translated into Spanish by Óscar Paúl Castro

Posted: February 1, 2013 Filed under: English, Langston Hughes, Spanish | Tags: Black History Month poems Comments Off on Langston Hughes: “Tarea para el segundo curso de inglés” / “Theme for English B”, translated into Spanish by Óscar Paúl CastroLangston Hughes (1 febrero 1902 – 1967)

“Tarea para el segundo curso de inglés”

.

El profesor nos dijo:

Pueden irse a casa.

Esta noche escribirán una página:

que lo que escriban venga de ustedes,

así expresarán algo auténtico.

.

Me pregunto si es así de simple.

Tengo veintidós años, soy de color, nací en Winston-Salem.

Ahí asistí a la escuela, después en Durham, después aquí.

La Universidad está sobre la colina, dominando Harlem.

Soy el único estudiante de color en la clase.

Las escaleras que descienden por la colina desembocan en Harlem:

después de atravesar un parque, cruzar la calle san Nicolás,

la Octava Avenida, la Séptima, llego hasta el edificio “Y”

― la YMCA de Harlem Branch ― donde tomo el elevador,

entro en mi cuarto, me siento y escribo esta página:

.

Para ti no debe ser fácil poder identificar lo que es auténtico, tampoco lo es

para mí a esta edad: veintidós años. Supongo, sin embargo, que en todo

lo que siento, veo y escucho, Harlem, te escucho a ti:

te escucho, me escuchas; tú y yo ―juntos― estamos en esta página.

(También escucho a Nueva York) ¿Quién eres―Quién soy?

Bien: me gusta comer, dormir, beber, estar enamorado.

Me gusta trabajar, leer, me gusta aprender, e intentar comprender el sentido de la vida.

Quisiera una pipa como regalo de Navidad,

quizás unos discos: Bessie, bebop, o Bach.

Supongo que el hecho de ser negro no significa que me gusten

cosas distintas a las que les gustan a personas de otras razas.

¿En esta página que escribo se notará mi color?

Ciertamente ―siendo lo que soy― no será una página en blanco.

Y sin embargo

será parte de usted, maestro.

Usted es blanco,

y aun así es parte de mí, como yo soy parte de usted.

Eso significa ser americano.

Quizá usted no quiera ser parte de mí a veces.

Y en ocasiones yo no quiero ser parte de usted.

Pero, indudablemente, ambos somos parte del otro.

Yo aprendo de usted,

y supongo que usted aprende de mí:

aun cuando usted es mayor ―y blanco―

y, de alguna forma, más libre.

.

Está es mi tarea del Segundo Curso de Inglés.

(1951)

. . .

Langston Hughes (born February 1st 1902, died 1967)

“Theme for English B”

.

The instructor said,

Go home and write

a page tonight.

And let that page come out of you –

Then, it will be true.

.

I wonder if it’s that simple?

I am twenty-two, coloured, born in Winston-Salem.

I went to school there, then Durham, then here

to this college on the hill above Harlem.

I am the only coloured student in my class.

The steps from the hill lead down into Harlem

through a park, then I cross St. Nicholas,

Eighth Avenue, Seventh, and I come to the Y,

the Harlem Branch Y, where I take the elevator

up to my room, sit down, and write this page:

.

It’s not easy to know what is true for you or me

at twenty-two, my age. But I guess I’m what

I feel and see and hear, Harlem, I hear you:

hear you, hear me – we two – you, me, talk on this page.

(I hear New York too.) Me – who?

Well, I like to eat, sleep, drink, and be in love.

I like to work, read, learn, and understand life.

I like a pipe for a Christmas present,

or records – Bessie, bop, or Bach.

I guess being coloured doesn’t make me not like

the same things other folks like who are other races.

So will my page be coloured that I write?

Being me, it will not be white.

But it will be

a part of you, instructor.

You are white –

yet a part of me, as I am a part of you.

That’s American.

Sometimes perhaps you don’t want to be a part of me.

Nor do I often want to be a part of you.

But we are, that’s true!

As I learn from you,

I guess you learn from me –

although you’re older – and white –

and somewhat more free.

.

This is my page for English B.

(1951)

. . .

Traducción en español © Óscar Paúl Castro (nace 1979, Culiacán, México)

Óscar Paúl Castro, un poeta y traductor, es licenciado en Lengua y Literatura Hispánicas por la Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa.

. . . . .

Love poems, Blues poems – from The Harlem Renaissance

Posted: February 1, 2013 Filed under: English, English: Black Canadian / American, Langston Hughes, Love poems and Blues poems – from The Harlem Renaissance | Tags: Black History Month poems Comments Off on Love poems, Blues poems – from The Harlem RenaissanceLove poems, Blues poems – from The Harlem Renaissance:

Langston Hughes verses composed between 1924 and 1930:

. . .

“Subway Face”

.

That I have been looking

For you all my life

Does not matter to you.

You do not know.

.

You never knew.

Nor did I.

Now you take the Harlem train uptown;

I take a local down.

(1924)

. . .

“Poem (2)” (To F. S.)

.

I loved my friend.

He went away from me.

There’s nothing more to say.

The poem ends,

Soft as it began –

I loved my friend.

(1925)

. . .

“Better”

.

Better in the quiet night

To sit and cry alone

Than rest my head on another’s shoulder

After you have gone.

.

Better, in the brilliant day,

Filled with sun and noise,

To listen to no song at all

Than hear another voice.

. . .

“Poem (4)” (To the Black Beloved)

.

Ah,

My black one,

Thou art not beautiful

Yet thou hast

A loveliness

Surpassing beauty.

.

Oh,

My black one,

Thou art not good

Yet thou hast

A purity

Surpassing goodness.

.

Ah,

My black one,

Thou art not luminous

Yet an altar of jewels,

An altar of shimmering jewels,

Would pale in the light

Of thy darkness,

Pale in the light

Of thy nightness.

. . .

“The Ring”

.

Love is the master of the ring

And life a circus tent.

What is this silly song you sing?

Love is the master of the ring.

.

I am afraid!

Afraid of Love

And of Love’s bitter whip!

Afraid,

Afraid of Love

And Love’s sharp, stinging whip.

.

What is this silly song you sing?

Love is the master of the ring.

(1926)

. . .

“Ma Man”

.

When ma man looks at me

He knocks me off ma feet.

When ma man looks at me

He knocks me off ma feet.

He’s got those ‘lectric-shockin’ eyes an’

De way he shocks me sho is sweet.

.

He kin play a banjo.

Lordy, he kin plunk, plunk, plunk.

He kin play a banjo.

I mean plunk, plunk…plunk, plunk.

He plays good when he’s sober

An’ better, better, better when he’s drunk.

.

Eagle-rockin’,

Daddy, eagle-rock with me.

Eagle rockin’,

Come an’ eagle-rock with me.

Honey baby,

Eagle-rockish as I kin be!

. . .

“Lament over Love”

.

I hope my child’ll

Never love a man.

I say I hope my child’ll

Never love a man.

Love can hurt you

Mo’n anything else can.

.

I’m goin’ down to the river

An’ I ain’t goin’ there to swim;

Down to the river,

Ain’t goin’ there to swim.

My true love’s left me

And I’m goin’ there to think about him.

.

Love is like whiskey,

Love is like red, red wine.

Love is like whiskey,

Like sweet red wine.

If you want to be happy

You got to love all the time.

.

I’m goin’ up in a tower

Tall as a tree is tall,

Up in a tower

Tall as a tree is tall.

Gonna think about my man –

And let my fool-self fall.

(1926)

. . .

“Dressed Up”

.

I had ma clothes cleaned

Just like new.

I put ’em on but

I still feels blue.

.

I bought a new hat,

Sho is fine,

But I wish I had back that

Old gal o’ mine.

.

I got new shoes –

They don’t hurt ma feet,

But I ain’t got nobody

For to call me sweet.

. . .

“To a Little Lover-Lass, Dead”

.

She

Who searched for lovers

In the night

Has gone the quiet way

Into the still,

Dark land of death

Beyond the rim of day.

.

Now like a little lonely waif

She walks

An endless street

And gives her kiss to nothingness.

Would God his lips were sweet!

. . .

“Harlem Night Song”

.

Come,

Let us roam the night together

Singing.

.

I love you.

Across

The Harlem roof-tops

Moon is shining.

Night sky is blue.

Stars are great drops

Of golden dew.

.

Down the street

A band is playing.

.

I love you.

.

Come,

Let us roam the night together

Singing.

. . .

“Passing Love”

.

Because you are to me a song

I must not sing you over-long.

.

Because you are to me a prayer

I cannot say you everywhere.

.

Because you are to me a rose –

You will not stay when summer goes.

(1927)

. . .

“Desire”

.

Desire to us

Was like a double death,

Swift dying

Of our mingled breath,

Evaporation

Of an unknown strange perfume

Between us quickly

In a naked

Room.

. . .

“Dreamer”

.

I take my dreams

And make of them a bronze vase,

And a wide round fountain

With a beautiful statue in its centre,

And a song with a broken heart,

And I ask you:

Do you understand my dreams?

Sometimes you say you do

And sometimes you say you don’t.

Either way

It doesn’t matter.

I continue to dream.

(1927)

. . .

“Lover’s Return”

.

My old time daddy

Came back home last night.

His face was pale and

His eyes didn’t look just right.

.

He says, “Mary, I’m

Comin’ home to you –

So sick and lonesome

I don’t know what to do.”

.

Oh, men treats women

Just like a pair o’ shoes –

You kicks ’em round and

Does ’em like you choose.

.

I looked at my daddy –

Lawd! and I wanted to cry.

He looked so thin –

Lawd! that I wanted to cry.

But the devil told me:

Damn a lover

Come home to die!

(1928)

. . .

“Hurt”

.

Who cares

About the hurt in your heart?

.

Make a song like this

for a jazz band to play:

Nobody cares.

Nobody cares.

Make a song like that

From your lips.

Nobody cares.

. . .

“Spring for Lovers”

.

Desire weaves its fantasy of dreams,

And all the world becomes a garden close

In which we wander, you and I together,

Believing in the symbol of the rose,

Believing only in the heart’s bright flower –

Forgetting – flowers wither in an hour.

(1930)

. . .

“Rent-Party Shout: For a Lady Dancer”

.

Whip it to a jelly!

Too bad Jim!

Mamie’s got ma man –

An’ I can’t find him.

Shake that thing! O!

Shake it slow!

That man I love is

Mean an’ low.

Pistol an’ razor!

Razor an’ gun!

If I sees man man he’d

Better run –

For I’ll shoot him in de shoulder,

Else I’ll cut him down,

Cause I knows I can find him

When he’s in de ground –

Then can’t no other women

Have him layin’ round.

So play it, Mr. Nappy!

Yo’ music’s fine!

I’m gonna kill that

Man o’ mine!

(1930)

. . . . .

In the manner of all great poets Langston Hughes (February 1st, 1902 – 1967) wrote love poems (and love-blues poems), using the voices and perspectives of both Man and Woman. In addition to such art, Hughes’ homosexuality, real though undisclosed during his lifetime, probably was responsible for the subtle and highly-original poet’s voice he employed for three of the poems included here: Subway Face, Poem (2), and Desire. Hughes was among a wealth of black migrants born in The South or the Mid-West who gravitated toward Harlem in New York City from about 1920 onward. Along with Countee Cullen, Zora Neale Hurston, Wallace Thurman and many others, Hughes became part of The Harlem Renaissance, that great-gorgeous fresh-flowering of Black-American culture.

. . . . .

Johnson, Fauset, Bennett: Black Blossoms of the 1920s

Posted: February 1, 2013 Filed under: English, Georgia Douglas Johnson, Gwendolyn Bennett, Helene Johnson, Jessie Redmon Fauset | Tags: Black History Month poems, Black-American women poets of the 1920s Comments Off on Johnson, Fauset, Bennett: Black Blossoms of the 1920s

ZP_Gwendolyn Bennett at her typewriter. She contributed to the academic journal Opportunity, had a story included in the infamous one-issue Fire! and her 1924 poem To Usward was “a rallying cry to the New Negro”.

Georgia Douglas Johnson (1880-1966) “Black Woman” (1922) . Don’t knock at the door, little child, I cannot let you in, You know not what a world this is Of cruelty and sin. Wait in the still eternity Until I come to you, The world is cruel, cruel, child, I cannot let you in! . Don’t knock at my heart, little one, I cannot bear the pain Of turning deaf-ear to your call Time and time again! You do not know the monster men Inhabiting the earth, Be still, be still, my precious child, I must not give you birth! . . . Georgia Douglas Johnson “Common Dust” .

And who shall separate the dust

What later we shall be:

Whose keen discerning eye will scan

And solve the mystery?

.

The high, the low, the rich, the poor,

The black, the white, the red,

And all the chromatique between,

Of whom shall it be said:

.

Here lies the dust of Africa;

Here are the sons of Rome;

Here lies the one unlabelled,

The world at large his home!

.

Can one then separate the dust?

Will mankind lie apart,

When life has settled back again

The same as from the start?

. . .

Jessie Redmon Fauset (1882-1961) “La Vie C'est La Vie” (1922) . On summer afternoons I sit Quiescent by you in the park And idly watch the sunbeams gild And tint the ash-trees' bark. . Or else I watch the squirrels frisk And chaffer in the grassy lane; And all the while I mark your voice Breaking with love and pain. . I know a woman who would give Her chance of heaven to take my place; To see the love-light in your eyes, The love-glow on your face! . And there's a man whose lightest word Can set my chilly blood afire; Fulfillment of his least behest Defines my life’s desire. . But he will none of me, nor I Of you. Nor you of her. 'Tis said The world is full of jests like these.— I wish that I were dead. . . .

Jessie Redmon Fauset

“Oriflamme”

.

“I can remember when I was a little young girl, how my old mammy would sit out of doors in the evenings and look up at the stars and groan,

and I would say, ‘Mammy, what makes you groan so?’ And she would say, ‘I am groaning to think of my poor children;

they do not know where I be and I don’t know where they be. I look up at the stars and they look up at the stars!’”

—Sojourner Truth (1797-1883)

. I think I see her sitting bowed and black, Stricken and seared with slavery's mortal scars, Reft of her children, lonely, anguished, yet Still looking at the stars. . Symbolic mother, we thy myriad sons, Pounding our stubborn hearts on Freedom's bars, Clutching our birthright, fight with faces set, Still visioning the stars! . . . Gwendolyn Bennett (1902-1981) “Hatred” (1926) . I shall hate you Like a dart of singing steel Shot through still air At even-tide, Or solemnly As pines are sober When they stand etched Against the sky. Hating you shall be a game Played with cool hands And slim fingers. Your heart will yearn For the lonely splendor Of the pine tree While rekindled fires In my eyes Shall wound you like swift arrows. Memory will lay its hands Upon your breast And you will understand My hatred. . . . Gwendolyn Bennett “Fantasy” (1927) . I sailed in my dreams to the Land of Night Where you were the dusk-eyed queen, And there in the pallor of moon-veiled light The loveliest things were seen ... . A slim-necked peacock sauntered there In a garden of lavender hues, And you were strange with your purple hair As you sat in your amethyst chair With your feet in your hyacinth shoes. . Oh, the moon gave a bluish light Through the trees in the land of dreams and night. I stood behind a bush of yellow-green And whistled a song to the dark-haired queen... . . .

Helene Johnson (1906-1995) was just that much younger than the other women poets,

and a letting-go of the conventions of 19th-century “romantic” verse form and literary style

plus an embracing of colloquial speech and Jazz rhythm is evident in the following poem, “Bottled”, which she wrote at the age of 21.

.

Helene Johnson

“Bottled” (1927)

.

Upstairs on the third floor

Of the 135th Street Library

In Harlem, I saw a little

Bottle of sand, brown sand,

Just like the kids make pies

Out of down on the beach.

But the label said: “This

Sand was taken from the Sahara desert.”

Imagine that! The Sahara desert!

Some bozo’s been all the way to Africa to get some sand.

And yesterday on Seventh Avenue

I saw a darky dressed to kill

In yellow gloves and swallowtail coat

And swirling at him. Me too,

At first, till I saw his face

When he stopped to hear a

Organ grinder grind out some jazz.

Boy! You should a seen that darky’s face!

It just shone. Gee, he was happy!

And he began to dance. No

Charleston or Black Bottom for him.

No sir. He danced just as dignified

And slow. No, not slow either.

Dignified and proud! You couldn’t

Call it slow, not with all the

Cuttin’ up he did. You would a died to see him.

The crowd kept yellin’ but he didn’t hear,

Just kept on dancin’ and twirlin’ that cane

And yellin’ out loud every once in a while.

I know the crowd thought he was coo-coo.

But say, I was where I could see his face,

.

And somehow, I could see him dancin’ in a jungle,

A real honest-to cripe jungle, and he wouldn’t leave on them

Trick clothes-those yaller shoes and yaller gloves

And swallowtail coat. He wouldn’t have on nothing.

And he wouldn’t be carrying no cane.

He’d be carrying a spear with a sharp fine point

Like the bayonets we had “over there.”

And the end of it would be dipped in some kind of

Hoo-doo poison. And he’d be dancin’ black and naked and

.

Gleaming.

And He’d have rings in his ears and on his nose

And bracelets and necklaces of elephants teeth.

Gee, I bet he’d be beautiful then all right.

No one would laugh at him then, I bet.

Say! That man that took that sand from the Sahara desert

And put it in a little bottle on a shelf in the library,

That’s what they done to this shine, ain’t it? Bottled him.

Trick shoes, trick coat, trick cane, trick everything-all glass-

But inside –

Gee, that poor shine!

ZP_Regina Anderson 1901-1993, Librarian at the 135th Street Harlem branch of the New York Public Library, playwright, and midwife to The Harlem Renaissance

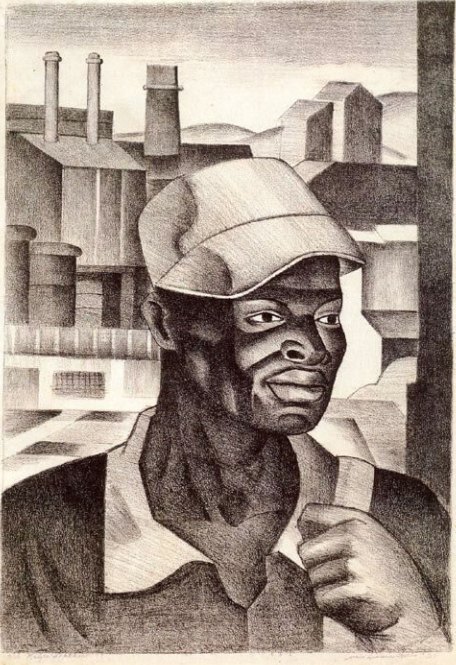

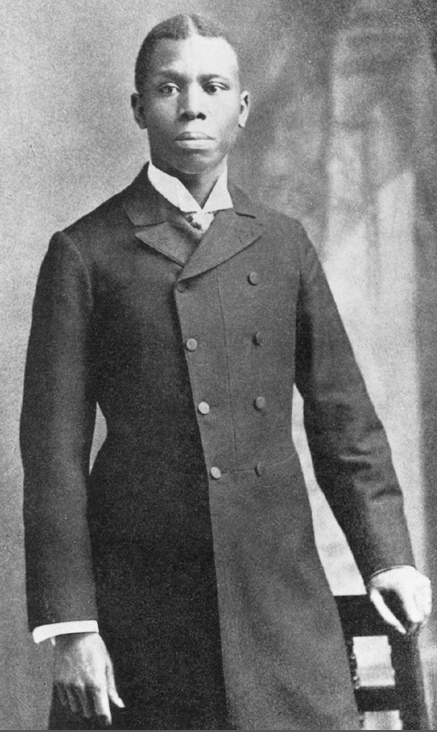

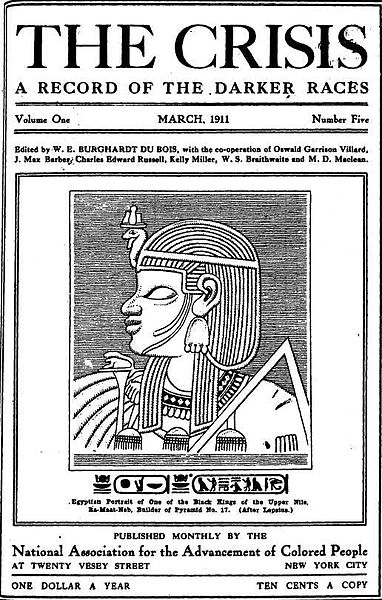

W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963) was a sociologist and civil-rights activist. He co-founded The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1909, and its monthly current-affairs journal, The Crisis – A Record of the Darker Races, which included poems, reviews and essays, was published from 1910 onward. Du Bois, as the editor of The Crisis, stated: “The object of this publication is to set forth those facts and arguments which show the danger of race prejudice, particularly as manifested today toward colored people. It takes its name from the fact that the editors believe that this is a critical time in the history of the advancement of men. Finally, its editorial page will stand for the rights of men, irrespective of color or race, for the highest ideals of American democracy, and for reasonable but earnest and persistent attempts to gain these rights and realize these ideals.”

Zócalo Poets will return February 2013 / Zócalo Poets…Volveremos en febrero de 2013

Posted: December 31, 2012 Filed under: English, Jakuren, Japanese, Oliver Herford, Yosano Hiroshi, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Zócalo Poets will return February 2013 / Zócalo Poets…Volveremos en febrero de 2013¿Eres poeta o poetisa?

¡Mándanos tus poemas – en cualquier idioma!

Are you a poet or poetess?

Send us your poems – in any language!

zocalopoets@hotmail.com

.

.

与謝野 鉄幹 / Yosano Hiroshi (1873-1935)

.

yama fukami /deep in the mountains /en lo profundo de la cordillera

haru to mo shiranu / beyond the knowledge of spring /

más allá del conocimiento de la primavera

matsu no to ni / on a pine bough door /sobre una puerta de ramas de pino

taedae kakaru / there are faintly suspended / hay, delicadamente suspendidos,

yuki no tamamizu / beads of liquid snow / gotas de nieve líquida.

. . .

Oliver Herford (1863-1935)

“I heard a bird sing”

.

I heard a bird sing

In the dark of December.

A magical thing

And sweet to remember.

.

“We are nearer to Spring

Than we were in September,”

I heard a bird sing

In the dark of December.

. . .

“Oí un pájaro, cantante pájaro” (Oliver Herford, 1863-1935)

.

Oí un pájaro, cantante pájaro,

En l’ oscuridad de diciembre

– algo mágico, esa voz, y

Dulce en mi recuerdo.

.

“Estamos más cerca de la primavera

Que estuvimos en septiembre.”

Oí un pájaro, cantante pájaro,

En la luz tenue, diciembre.

. . .

藤原定長 / Jakuren (1139-1202)

.

kaze wa kiyoshi / the breeze is fresh / fresca, la brisa,

tsuki wa sayakeshi / the moon is bright; / brillante, la luna;

iza tomoni / come, we shall dance till dawn, / ven, bailaremos hasta el alba,

odori akasan / and say farewell to age… / y a la vejez diremos Adiós.

oi no nagori ni…

.

Translations of ‘tanka’ poems by Yosano Hiroshi and Jakuren from Japanese © Michael Haldane

Translations into Spanish / Traducciones al español: Alexander Best

. . . . .

“Just enough snow to make you look carefully at familiar streets”: the Haiku of Richard Wright

Posted: December 27, 2012 Filed under: English, Richard Wright | Tags: Haiku written in English Comments Off on “Just enough snow to make you look carefully at familiar streets”: the Haiku of Richard Wright.

Just enough snow

To make you look carefully

At familiar streets.

.

On winter mornings

The candle shows faint markings

Of the teeth of rats.

.

In the falling snow

A laughing boy holds out his palms

Until they are white.

.

The snowball I threw

Was caught in a net of flakes

And wafted away.

.

.

A freezing morning:

I left a bit of my skin

On the broomstick handle.

.

The Christmas season:

A whore is painting her lips

Larger than they are.

.

.

Standing patiently

The horse grants the snowflakes

A home on his back.

.

In the falling snow

the thick wool of the sheep

gives off a faint vapour.

.

Entering my town

In a fall of heavy snow

I feel a stranger.

.

In this rented room

One more winter stands outside

My dirty windowpane.

.

.

The call of a bird

sends a solid cake of snow

sliding off the roof.

.

I slept so long and sound,

but I did not know why until

I saw the snow outside.

.

The smell of sunny snow

is swelling the icy air –

the world grows bigger.

.

The cold is so sharp

that the shadow of the house

bites into the snow.

.

What do they tell you

each night, O winter moon,

before they roll you out?

.

Burning out its time

And timing its own burning,

One lovely candle.

. . .

Richard Nathaniel Wright (born Roxie, Mississippi,1908, died Paris, 1960) was a rigorous Black-American short-story writer, novelist, essayist, and lecturer. He joined the Communist Party USA in 1933 and was Harlem editor for the newspaper “Daily Worker”. Intensely racial themes were pervasive in his work and famous books such as Uncle Tom’s Children (1938), Native Son (1940) and Black Boy (1945) were sometimes criticized for their portrayal of violence – yet, as the 1960s’ voices of Black Power would phrase it – a generation later – he was just “telling it like it is.”

.

Wright discovered Haiku around 1958 and began to write obsessively in this Japanese form using what was becoming the standard “shape” in English: 5 syllables, 7 syllables, 5 syllables, in three separate lines, and with the final line adding an element of surprise – delicate or otherwise. One of Haiku’s objectives is, to paraphrase Matsuo Bashō, a 17th-century Japanese poet: In a haiku poem, if you reveal 70 to 80 percent of the subject – that’s good – but if you show only 50 to 60 percent, then the reader or listener will never tire of that particular poem.

What do you think – does Wright succeed?

.

The 4 Seasons are themes in Haiku; here we have presented a palmful of Wright’s Winter haiku. Wright was frequently bedridden during the last year of his life and his daughter Julia has said that her father’s haiku were “self-developed antidotes against illness, and that breaking down words into syllables matched the shortness of his breath.” She also added: her father was striving “to spin these poems of light out of the gathering darkness.”

We are grateful to poet Ty Hadman for these quotations from Wright’s daughter, Julia.

. . .

The above haiku were selected from the volume Richard Wright: Haiku, This Other World, published posthumously, in 1998, after a collection of several thousand Haiku composed by Wright was ‘ found ‘ in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Yale University.

. . . . .

Kwanzaa yenu iwe na heri! Harambee! / Happy Kwanzaa – Let’s all pull together!

Posted: December 26, 2012 Filed under: English, Swahili | Tags: Kwanzaa poems Comments Off on Kwanzaa yenu iwe na heri! Harambee! / Happy Kwanzaa – Let’s all pull together!.

Vickie M. Oliver-Lawson

“Remembering the Seven Principles of Kwanzaa”

.

First fruits is what the name Kwanzaa means

It’s celebrated everywhere by kings and queens

Based on seven principles that still exist

If you check out this rhyme, you’ll get the gist

.

Umoja, a Swahili name for unity

Is the goal we strive for across this country

Kujichagulia means self-determination

We define ourselves, a strong creation.

Ujima or collective work and responsibility

Is how we build and maintain our own community

For if my people have a problem, then so do I

So let’s work through it together with our heads held high.

.

Ujamaa meaning cooperative economics is nothing new

We support and run our own stores and other businesses, too

Nia is purpose, us developing our potential

As we build our community strong to the Nth exponential

Kuumba is the creative force which lies within our call

As we leave our community much better for all

As a people, let’s move forward by extending our hand

For Imani is the faith to believe that we can.

.

These seven principles help to make our nation strong

If you live to these ideals, you can’t go wrong

But you must first determine your own mentality

And believe in yourself as you want you to be

And no matter how far, work hard to reach your goal

As we stand, as a people, heads up, fearless and bold.

.

Ms. Vickie M. Oliver-Lawson is a retired public school administrator, wife, and mother from Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.A. She is the author of several books, including “Vocal Moments”, “In the Quilting Tradition” and “Timeless Influences” (2009). She contributes to the Examiner news website.

. . .

Journalist Will Jones writes:

“ Kwanzaa was created as an Afrocentric holiday in 1966 by the black-militant history professor Maulana Karenga, and was intended to be a secular cultural celebration rooted in notions of African pride and community empowerment, rather than in any long-standing religious tradition like Christmas or Hanukkah. And in its very nature, Kwanzaa seems as appealing to many as it is appalling to others. It certainly presumes a level of self-awareness and racial identity that some can find off-putting. But at the same time, many who celebrate Kwanzaa or in tandem with Christmas say the holiday is less about being counter to any other mainstream holiday, and more of a vehicle to celebrate African-American culture and a shared heritage.

Kwanzaa, which means “first fruits” in Swahili, revolves around seven core principles, each celebrated on one day of the week-long observance, with simple, often homemade gifts and feasts. Each day a red, black or green candle is lit in a Kinara in honour of each of the seven principles: Umoja, unity; Kujichagulia, self-determination; Ujima, collective work and responsibility; Ujamaa, cooperative economics; Nia, purpose; Kuumba, creativity; and Imani, faith. ”

Kwanzaa, beginning always on December 26th, lasts seven days, being completed on January 1st.

. . . . .