Mi’kmaw I am: Poems of Rita Joe + We are the Dreamers

Posted: April 11, 2013 Filed under: English, Mi'kmaq / Míkmawísimk, Mi'kmaw I am: Poems of Rita Joe + We are the Dreamers, Rita Joe Comments Off on Mi’kmaw I am: Poems of Rita Joe + We are the DreamersRita Joe

(Mi’kmaw poet, 1932-2007, Whycocomagh, Nova Scotia, Canada)

.

“A Mi’kmaw Cure-All for Ingrown Toenail”

.

I have a comical story for ingrown toenail

I want to share with everybody.

The person I love and admire is a friend.

This is her cure-all for an elderly problem.

She bought rubber boots one size larger

And put salted water above the toe

Then wore the boots all day.

When evening came they cut easy,

The ingrown problem much better.

I laughed when I heard the story.

It is because I have the same tender distress

So might try the Mi’kmaw cure-all.

The boots are there, just add the salted water

And laugh away the pesky sore.

I’m even thinking of bottling for later use.

. . .

“Street Names”

.

In Eskasoni there were never any street names, just name areas.

There was Qam’sipuk (Across The River),

74th Street now, you guess why the name.

Apamuek, central part of Eskasoni, the home of Apamu.

New York Corner, never knew the reason for the name.

There is Gabriel Street, the church Gabriel Centre.

Espise’k, Very Deep Water.

Beach Road, naturally the beach road.

Mickey’s Lane. There must be a Mickey there.

Spencer’s Lane, Spencer lives there, why not Arlene? His wife.

Cremo’s Lane, the last name of many people.

Crane Cove Road, the location of Crane Cove Fisheries.

Pine Lane, a beautiful spot, like everywhere else in Eskasoni.

Silverwood Lane, the place of silverwood.

George Street, bet you can’t guess who lives there.

Denny’s Lane, the last name of many Dennys.

Paul’s Lane, there are many Pauls, Poqqatla’naq.

Johnson Place, many Johnsons.

Morris Lane, guess who?

Horseshoe Drive, considering no horses in Eskasoni.

Beacon Hill, elegant place name,

I used to work at Beacon Hill Hospital in Boston.

Mountain Road,

A’nslm Road, my son-in-law Tom Sylliboy, daughter,

three grandchildren live there,

and Lisa Marie, their poodle.

Apamuekewawti, near where I live, come visit.

. . .

“Ankita’si (I think)”

.

A thought is to catch an idea

Between two minds.

Swinging to and fro

From English to Native,

Which one will I create, fulfill

Which one to roll along until arriving

To settle, still.

.

I know, my mind says to me

I know, try Mi’kmaw…

Ankite’tm

Na kelu’lk we’jitu (I find beauty)

Ankite’tm

Me’ we’jitutes (I will find more)

Ankita’si me’ (I think some more)

.

We’jitu na!*

.

*We’jitu na! – I find!

. . .

“Plawej and L’nui’site’w” (Partridge and Indian-Speaking Priest)

.

Once there was an Indian-speaking priest

Who learned Mi’kmaw from his flock.

He spoke the language the best he knew how

But sometimes got stuck.

They called him L’nui’site’w out of respect to him

And loving the man, he meant a lot to them.

At specific times he heard their confessions

They followed the rules, walking to the little church.

A widow woman was strolling through the village

On her way there, when one hunter gave her a day-old plawej

She took the partridge, putting it inside her coat

Thanking the couple, going her way.

At confession, the priest asked, “What is the smell?”

In Mi’kmaw she said, “My plawej.”

He gave blessing and sent her on her way.

The next day he gave a long sermon, ending with the words

“Keep up the good lives you are leading,

but wash your plawejk.”

The women giggled, he never knew why.

To this day there is a saying, they laugh and cry.

Whatever you do, wherever you go,

Always wash your plawejk.

. . .

“I Washed His Feet”

.

In early morning she burst into my kitchen. “I got something to

tell you, I was disrespectful to him,” she said. “Who were you

disrespectful to?” I asked. “Se’sus*,” she said. I was overwhelmed

by her statement. Caroline is my second youngest.

How in the world can one be disrespectful to someone we

never see? It was in a dream, there were three knocks on the

door. I opened the door, “Oh my God you’re here.” He came in

but stood against the wall. “I do not want to track dirt on your

floor,” he said. I told him not to mind the floor but come in, that

tea and lu’sknikn (bannock) will be ready in a moment. He ate and

thanked me… But then he asked if I would wash his feet, he

looked kind and normal, but a bit tired. In the dream, she said, I

took an old t-shirt and wet it with warm water and washed his

feet, carefully cleaning them, especially between his toes. I

wiped them off and put his sandals back on. After I was finished

I put the TV on, he leaned forward looking at the television.

His hair fell forward, he pushed it away from his face. I

removed a tendril away from his eye. “I am tired of my hair,”

he said. “Why don’t you wear a ponytail or have it braided?”

He said all right but asked me to teach him how to braid. I

stood beside him and touched his soft hair and saw a tear in

his eye, using my pinky finger to wipe the tear away. He smiled

gently. I then showed him how to braid his hair, guiding his

hands on how it was done. He caught on real easy. He was

happy. He thanked me for everything. You are welcome any

time you want to visit. He smiled as he walked out. He is just

showing us he is around at any time, even in 1997.

I was honoured to hear the story firsthand.

.

* Se’sus – Jesus

. . .

“Apiksiktuaqn (To forgive, be forgiven)”

.

A friend of mine in Eskasoni Reservation

Entered the woods and fasted for eight days.

I awaited the eight days to see him

I wanted to know what he learned from the sune’wit.

To my mind this is the ultimate for a cause

Learning the ways, an open door, derive.

At the time he did it, it was for

The people, the oncoming pow-wow

The journey to know, rationalize, spiritual growth.

When he drew near, a feeling like a parent on me

He was my son, I wanted to listen.

He talked fast, at times with a rush of words

As if to relate all, but sadness took over.

I hugged him and said, “Don’t talk if it is too sad.”

The spell was broken, he could say no more.

The one thing I heard him say, “Apiksiktuaqn nuta’ykw”,

For months it stayed on my mind.

Now it may go away as I write

Because this is the past, the present, the future.

.

I wish this would happen to all of us

Unity then will be the world over

My friend carried a message

Let us listen.

.

sune’wit – to fast, abstain from food

Apiksiktuaqn nuta’ykw – To forgive, be forgiven.

.

All of the above poems – from Rita Joe’s 1999 collection We are the Dreamers,

(published by Breton Books, Wreck Cove, Nova Scotia)

. . . . .

The following is a selection from the 26 numbered poems of Poems of Rita Joe

(published in 1978 by Abanaki Press, Halifax, Nova Scotia)

.

6

.

Wen net ki’l?

Pipanimit nuji-kina’muet ta’n jipalk.

Netakei, aq i’-naqawey;

Koqoey?

.

Ktikik nuji-kina’masultite’wk kimelmultijik.

Na epas’si, taqawajitutm,

Aq elui’tmasi

Na na’kwek.

.

Espi-kjijiteketes,

Ma’jipajita’siw.

Espitutmikewey kina’matneweyiktuk eyk,

Aq kinua’tuates pa’ qlaiwaqnn ni’n nikmaq.

.

Who are you?

Question from a teacher feared.

Blushing, I stammered

What?

.

Other students tittered.

I sat down forlorn, dejected,

And made a vow

That day

.

To be great in all learnings,

No more uncertain.

My pride lives in my education,

And I will relate wonders to my people.

. . .

10

.

Ai! Mu knu’kwaqnn,

Mu nuji-wi’kikaqnn,

Mu weskitaqawikasinukul kisna

mikekni-napuikasinukul

Kekinua’tuenukul wlakue’l

pa’qalaiwaqnn.

.

Ta’n teluji-mtua’lukwi’tij nuji-

kina’mua’tijik a.

.

Ke’ kwilmi’tij,

Maqamikewe’l wisunn,

Apaqte’l wisunn,

Sipu’l;

Mukk kas’tu mikuite’tmaqnmk

Ula knu’kwaqnn.

.

Ki’ welaptimikl

Kmtne’l samqwann nisitk,

Kesikawitkl sipu’l.

Ula na kis-napui’kmu’kl

Mikuite’tmaqanminaq.

Nuji-kina’masultioq,

we’jitutoqsip ta’n kisite’tmekl

Wisunn aq ta’n pa’-qi-klu’lk,

Tepqatmi’tij L’nu weja’tekemk

weji-nsituita’timk.

.

Aye! no monuments,

No literature,

No scrolls or canvas-drawn pictures

Relate the wonders of our yesterday.

.

How frustrated the searchings

of the educators.

.

Let them find

Land names,

Titles of seas,

Rivers;

Wipe them not from memory.

These are our monuments.

.

Breathtaking views –

Waterfalls on a mountain,

Fast flowing rivers.

These are our sketches

Committed to our memory.

Scholars, you will find our art

In names and scenery,

Betrothed to the Indian

since time began.

. . .

14

.

Kiknu na ula maqmikew

Ta’n asoqmisk wju’sn kmtnji’jl

Aq wastewik maqmikew

Aq tekik wju’sn.

.

Kesatm na telite’tm L’nueymk,

Paqlite’tm, mu kelninukw koqoey;

Aq ankamkik kloqoejk

Wejkwakitmui’tij klusuaqn.

Nemitaq ekil na tepknuset tekik wsiskw

Elapekismatl wta’piml samqwan-iktuk.

.

Teli-ankamkuk

Nkutey nike’ kinu tepknuset

Wej-wskwijnuulti’kw,

Pawikuti’kw,

Tujiw keska’ykw, tujiw apaji-ne’ita’ykw

Kutey nike’ mu pessipketenukek

iapjiweyey.

.

Mimajuaqnminu siawiaq

Mi’soqo kikisu’a’ti’kw aq nestuo’lti’kw.

Na nuku’ kaqiaq.

Mu na nuku’eimukkw,

Pasik naqtimu’k

L’nu’ qamiksuti ta’n mu nepknukw.

.

Our home is in this country

Across the windswept hills

With snow on fields.

The cold air.

.

I like to think of our native life,

Curious, free;

And look at the stars

Sending icy messages.

My eyes see the cold face of the moon

Cast his net over the bay.

.

It seems

We are like the moon –

Born,

Grow slowly,

Then fade away, to reappear again

In a never-ending cycle.

.

Our lives go on

Until we are old and wise.

Then end.

We are no more,

Except we leave

A heritage that never dies.

. . .

19

.

Klusuaqnn mu nuku’ nuta’nukul

Tetpaqi-nsitasin.

Mimkwatasik koqoey wettaqne’wasik

L’nueyey iktuk ta’n keska’q

Mu a’tukwaqn eytnukw klusuaqney

panaknutk pewatmikewey

Ta’n teli-kjijituekip seyeimik

.

Espe’k L’nu’qamiksuti,

Kelo’tmuinamitt ajipjitasuti.

Apoqnmui kwilm nsituowey

Ewikasik ntinink,

Apoqnmui kaqma’si;

Pitoqsi aq melkiknay.

.

Mi’kmaw na ni’n;

Mukk skmatmu piluey koqoey wja’tuin.

.

Words no longer need

Clear meanings.

Hidden things proceed from a lost legacy.

No tale in words bares our desire, hunger,

The freedom we have known.

.

A heritage of honour

Sustains our hopes.

Help me search the meaning

Written in my life,

Help me stand again

Tall and mighty.

.

Mi’kmaw I am;

Expect nothing else from me.

Rita Joe, born Rita Bernard in 1932, was a poet, a writer, and a human rights activist. Born in Whycocomagh, Nova Scotia, Canada, she was raised in foster homes after being orphaned in 1942. She was educated at Shubenacadie Residential School where she learned English – and that experience was also the impetus for writing a good number of her poems. (“I Lost My Talk” is about having her Mi’kmaq language denied at school.) While identity-erasure was part of her Canadian upbringing, still she managed in her writing – and in her direct, in-person activism – to promote compassion and cooperation between Peoples. Rita married Frank Joe in 1954 and together they raised ten children at their home in The Eskasoni First Nation, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. It was in her thirties, in the 1960s, that Joe began to write poetry so as to counteract the negative images of Native peoples found in the books that her children read. The Poems of Rita Joe, from 1978, was the first published book of Mi’kmaq poetry by a Mi’kmaw author. Rita Joe died in 2007, at the age of 75, after struggling with Parkinson’s Disease. Her daughters found a revision of her last poem “October Song” on her typewriter. The poem reads: “On the day I am blue, I go again to the wood where the tree is swaying, arms touching you like a friend, and the sound of the wind so alone like I am; whispers here, whispers there, come and just be my friend.”

. . . . .

Pauline Johnson / “Tekahionwake”: “Let her be natural”

Posted: April 11, 2013 Filed under: English, Pauline Johnson, Pauline Johnson's "Flint & Feather" Comments Off on Pauline Johnson / “Tekahionwake”: “Let her be natural”

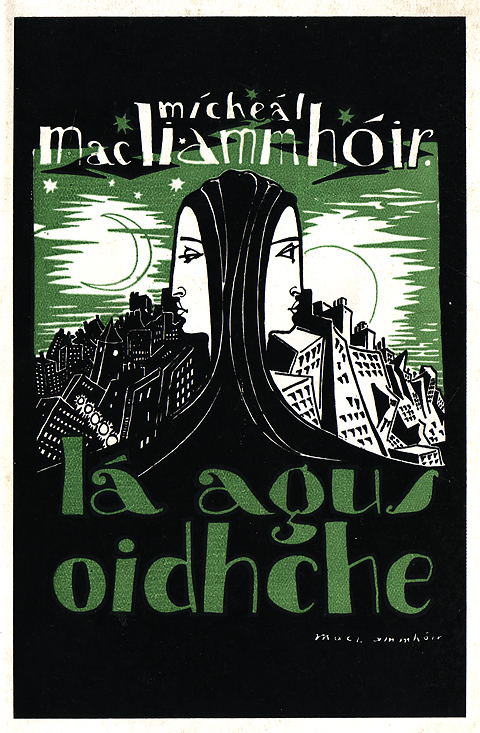

ZP_E. Pauline Johnson gathered together her complete poems, though others have since been discovered, for publication in 1912, the year before her death. In her Author’s Forward to Flint and Feather she writes: This collection of verse I have named Flint and Feather because of the association of ideas. Flint suggests the Red man’s weapons of war, it is the arrow tip, the heart-quality of mine own people, let it therefore apply to those poems that touch upon Indian life and love. The lyrical verse herein is as a Skyward floating feather, Sailing on summer air. And yet that feather may be the eagle plume that crests the head of a warrior chief; so both flint and feather bear the hall-mark of my Mohawk blood._Book jacket shown here is from a 1930s edition of Flint and Feather.

Pauline Johnson / “Tekahionwake”

(1861 – 1913, born at Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation, Ontario, Canada)

.

“The Cattle Thief”

.

They were coming across the prairie, they were

galloping hard and fast;

For the eyes of those desperate riders had sighted

their man at last –

Sighted him off to Eastward, where the Cree

encampment lay,

Where the cotton woods fringed the river, miles and

miles away.

Mistake him? Never! Mistake him? the famous

Eagle Chief!

That terror to all the settlers, that desperate Cattle

Thief –

That monstrous, fearless Indian, who lorded it over

the plain,

Who thieved and raided, and scouted, who rode like

a hurricane!

But they’ve tracked him across the prairie; they’ve

followed him hard and fast;

For those desperate English settlers have sighted

their man at last.

.

Up they wheeled to the tepees, all their British

blood aflame,

Bent on bullets and bloodshed, bent on bringing

down their game;

But they searched in vain for the Cattle Thief: that

lion had left his lair,

And they cursed like a troop of demons – for the women

alone were there.

“The sneaking Indian coward,” they hissed; “he

hides while yet he can;

He’ll come in the night for cattle, but he’s scared

to face a man.”

“Never!” and up from the cotton woods rang the

voice of Eagle Chief;

And right out into the open stepped, unarmed, the

Cattle Thief.

Was that the game they had coveted? Scarce fifty

years had rolled

Over that fleshless, hungry frame, starved to the

bone and old;

Over that wrinkled, tawny skin, unfed by the

warmth of blood.

Over those hungry, hollow eyes that glared for the

sight of food.

.

He turned, like a hunted lion: “I know not fear,”

said he;

And the words outleapt from his shrunken lips in

the language of the Cree.

“I’ll fight you, white-skins, one by one, till I

kill you all,” he said;

But the threat was scarcely uttered, ere a dozen

balls of lead

Whizzed through the air about him like a shower

of metal rain,

And the gaunt old Indian Cattle Thief dropped

dead on the open plain.

And that band of cursing settlers gave one

triumphant yell,

And rushed like a pack of demons on the body that

writhed and fell.

“Cut the fiend up into inches, throw his carcass

on the plain;

Let the wolves eat the cursed Indian, he’d have

treated us the same.”

A dozen hands responded, a dozen knives gleamed

high,

But the first stroke was arrested by a woman’s

strange, wild cry.

And out into the open, with a courage past

belief,

She dashed, and spread her blanket o’er the corpse

of the Cattle Thief;

And the words outleapt from her shrunken lips in

the language of the Cree,

“If you mean to touch that body, you must cut

your way through me.”

And that band of cursing settlers dropped

backward one by one,

For they knew that an Indian woman roused, was

a woman to let alone.

And then she raved in a frenzy that they scarcely

understood,

Raved of the wrongs she had suffered since her

earliest babyhood:

“Stand back, stand back, you white-skins, touch

that dead man to your shame;

You have stolen my father’s spirit, but his body I

only claim.

You have killed him, but you shall not dare to

touch him now he’s dead.

You have cursed, and called him a Cattle Thief,

though you robbed him first of bread –

Robbed him and robbed my people – look there, at

that shrunken face,

Starved with a hollow hunger, we owe to you and

your race.

What have you left to us of land, what have you

left of game,

What have you brought but evil, and curses since

you came?

How have you paid us for our game? how paid us

for our land?

By a book, to save our souls from the sins you

brought in your other hand.

Go back with your new religion, we never have

understood

Your robbing an Indian’s body, and mocking his

soul with food.

Go back with your new religion, and find – if find

you can –

The honest man you have ever made from out a

starving man.

You say your cattle are not ours, your meat is not

our meat;

When you pay for the land you live in, we’ll pay

for the meat we eat.

Give back our land and our country, give back our

herds of game;

Give back the furs and the forests that were ours

before you came;

Give back the peace and the plenty. Then come

with your new belief,

And blame, if you dare, the hunger that drove him to

be a thief.”

. . .

“A Cry from an Indian Wife” (1885)

.

My forest brave, my Red-skin love, farewell;

We may not meet to-morrow; who can tell

What mighty ills befall our little band,

Or what you’ll suffer from the white man’s hand?

Here is your knife! I thought ’twas sheathed for aye.

No roaming bison calls for it to-day;

No hide of prairie cattle will it maim;

The plains are bare, it seeks a nobler game:

‘Twill drink the life-blood of a soldier host.

Go; rise and strike, no matter what the cost.

Yet stay. Revolt not at the Union Jack,

Nor raise Thy hand against this stripling pack

Of white-faced warriors, marching West to quell

Our fallen tribe that rises to rebel.

They all are young and beautiful and good;

Curse to the war that drinks their harmless blood.

Curse to the fate that brought them from the East

To be our chiefs – to make our nation least

That breathes the air of this vast continent.

Still their new rule and council is well meant.

They but forget we Indians owned the land

From ocean unto ocean; that they stand

Upon a soil that centuries agone

Was our sole kingdom and our right alone.

They never think how they would feel to-day,

If some great nation came from far away,

Wresting their country from their hapless braves,

Giving what they gave us – but wars and graves.

Then go and strike for liberty and life,

And bring back honour to your Indian wife.

Your wife? Ah, what of that, who cares for me?

Who pities my poor love and agony?

What white-robed priest prays for your safety here,

As prayer is said for every volunteer

That swells the ranks that Canada sends out?

Who prays for vict’ry for the Indian scout?

Who prays for our poor nation lying low?

None – therefore take your tomahawk and go.

My heart may break and burn into its core,

But I am strong to bid you go to war.

Yet stay, my heart is not the only one

That grieves the loss of husband and of son;

Think of the mothers o’er the inland seas;

Think of the pale-faced maiden on her knees;

One pleads her God to guard some sweet-faced child

That marches on toward the North-West wild.

The other prays to shield her love from harm,

To strengthen his young, proud uplifted arm.

Ah, how her white face quivers thus to think,

Your tomahawk his life’s best blood will drink.

She never thinks of my wild aching breast,

Nor prays for your dark face and eagle crest

Endangered by a thousand rifle balls,

My heart the target if my warrior falls.

O! coward self I hesitate no more;

Go forth, and win the glories of the war.

Go forth, nor bend to greed of white men’s hands,

By right, by birth we Indians own these lands,

Though starved, crushed, plundered, lies our nation low…

Perhaps the white man’s God has willed it so.

.

Editor’s note: “the war” referred to in Johnson’s poem is The NorthWest Rebellion (or NorthWest Resistance) of 1885, led by Louis Riel.

. . .

“The Wolf”

.

Like a grey shadow lurking in the light,

He ventures forth along the edge of night;

With silent foot he scouts the coulie’s rim

And scents the carrion awaiting him.

His savage eyeballs lurid with a flare

Seen but in unfed beasts which leave their lair

To wrangle with their fellows for a meal

Of bones ill-covered. Sets he forth to steal,

To search and snarl and forage hungrily;

A worthless prairie vagabond is he.

Luckless the settler’s heifer which astray

Falls to his fangs and violence a prey;

Useless her blatant calling when his teeth

Are fast upon her quivering flank–beneath

His fell voracity she falls and dies

With inarticulate and piteous cries,

Unheard, unheeded in the barren waste,

To be devoured with savage greed and haste.

Up the horizon once again he prowls

And far across its desolation howls;

Sneaking and satisfied his lair he gains

And leaves her bones to bleach upon the plains.

. . .

“The Indian Corn Planter”

.

He needs must leave the trapping and the chase,

For mating game his arrows ne’er despoil,

And from the hunter’s heaven turn his face,

To wring some promise from the dormant soil.

.

He needs must leave the lodge that wintered him,

The enervating fires, the blanket bed–

The women’s dulcet voices, for the grim

Realities of labouring for bread.

.

So goes he forth beneath the planter’s moon

With sack of seed that pledges large increase,

His simple pagan faith knows night and noon,

Heat, cold, seedtime and harvest shall not cease.

.

And yielding to his needs, this honest sod,

Brown as the hand that tills it, moist with rain,

Teeming with ripe fulfilment, true as God,

With fostering richness, mothers every grain.

. . .

Emily Pauline Johnson (1861 – 1913) took on the Mohawk-language name Tekahionwake (meaning “double life”) around the time, as a young adult, she became aware of her ability not only as a woman who was writing poetry but also as a performer. Words such as transgressive and performativity – belovéd of academics in the 21st century – were words she mightn’t have known yet she “enacted” their meanings – and without the cadre of professionals to chatter about “who she really was”. And who was she – really? Well, she was complex – in some ways uncategorizable. A young woman who helped to support her widowed mother (her father, Brantford Six Nations Chief George Henry Martin Johnson (Onwanonsyshon) died in 1884) via the publication of her sentimental-exotic yet oddly-truthful poems; whose attachment to her father’s Native-ness was deeply felt during the onset of the Erasure Period chapter in First-Nations history in that New Nation – Canada. Pauline Johnson was mixed-race – Mohawk father of chieftain lineage, mother (Emily Susana Howells), a kind of English “rose” in a young British-colonial country. Enamoured of The Song of Hiawatha, and of Wacousta – Pauline was yet entranced by and deeply listened to the Native oral histories of John Smoke Johnson, her paternal grandfather. This was Pauline Johnson.

From about 1892 until 1909, Johnson, aided by impresario Frank Yeigh, toured as “The Mohawk Princess”, orating passionate poem-recitals while decked out in a mish-mashed Native costume which presented to Late-Victorian and Edwardian-era audiences a glamorous spectacle of Indian-ness. In the July/August 2012 issue of the Canadian magazine The Walrus, Emily Landau writes: “…and although her (Johnson’s) branding played into the stereotypes, her stories broke (the audiences) down.” Poems such as “The Indian Thief” and “A Cry from an Indian Wife” (both featured here) gave Native women a voice – using Victorian melodrama to present brief morality tales where what the Native woman says is right. Landau remarks that Johnson performed with “a mix of poise and campy histrionics. In a trademark flourish, she (would) shed the buckskin during intermission, returning in a staid silk evening gown and pumps, eliciting gasps from spectators as they marveled at the transformation. The two modes of dress served as an external manifestation of Johnson’s own dual identity: her (other) name, Tekahionwake, meant “double life” in Mohawk.”

Landau continues: “In an 1892 essay entitled “A Strong Race Opinion: On the Indian Girl in Modern Fiction,” Johnson called out white writers for their generic, latently racist depictions of Native femininity. Without fail, she says, the Indian girl, always named Winona or some such, has no tribal specificity, merely serving as a self-sacrificing, mentally unhinged outlet for the white hero’s magnanimity. Johnson entreated writers to give their “Indian girl” characters the same dignity and distinction as they did their white characters. “Let the Indian girl in fiction develop from the ‘dog-like,’ ‘fawn-like,’ ‘deer-footed,’ ‘fire-eyed,’ ‘crouching,’ ‘submissive’ book heroine into something of the quiet, sweet womanly woman if she is wild, or the everyday, natural, laughing girl she is if cultivated and educated; let her be natural,” she wrote, “even if the author is not competent to give her tribal characteristics.”

In her own act, Johnson drew from the dominant white theatrical modes. Melodrama, the most popular form in the late nineteenth century, was characterized by an excess of spectacle, histrionic gestures, and amplified emotions. With her over-the-top theatrics, she was a hit with crowds hungry for sentiment. One of her most popular stories, “A Red Girl’s Reasoning,” tells of a young half-Indian woman who leaves her husband after he refuses to recognize the legitimacy of her nation’s rituals; another heroine, the half-Cree Esther of “As It Was in the Beginning,” kills her faithless white lover.”

Johnson stopped touring in 1909. She had developed breast cancer, and worsening health led to early retirement. Settling in Vancouver, she still wrote – adapting stories as told to her by her friend, Squamish Chief Joseph Capilano. Johnson died in 1913; a monument – and her ashes – are in Vancouver’s Stanley Park.

And – we quote Landau again: “…Enterprising as she was, Johnson was also an idealist. Her proud biracial identity, within which her Aboriginal and European selves peacefully coexisted, constituted an anomaly in an era when race was considered a fixed trait. The unified persona she presented onstage, nurtured in her childhood and reflected in her writings, represented more than just an amplified, campy theatrical ruse: it was a vision of what she imagined for Canada. Surveying Canada’s beaming multiculturalism today, flawed as it may be, Johnson seems like quite an oracle.”

.

We wish to thank editor Emily Landau of Toronto Life for her critical analysis of the career of Pauline Johnson.

. . . . .

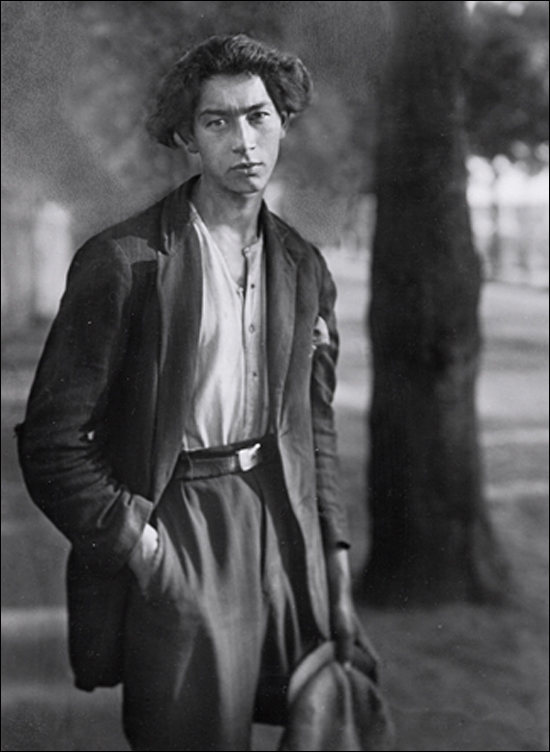

“Bright Horizon” by Ahmad Shamlu احمد شاملو

Posted: March 29, 2013 Filed under: Bright Horizon by Ahmad Shamlu, English, Farsi / Persian | Tags: Easter poems Comments Off on “Bright Horizon” by Ahmad Shamlu احمد شاملواحمد شاملو

Ahmad Shamlu (1925-2000, Tehran, Iran)

Ahmad Shamlu (1925-2000, Tehran, Iran)

“Bright Horizon”

.

Bright horizon

Some day we will find our doves

Kindness will take Beauty by the hand

.

That day – the least song will be a kiss

and every human being be brother to

every other human being

.

That day – house doors will not be shut

Locks will be but legends

And the Heart be enough for Living

.

The day – that the meaning of all speech is loving

so one won’t have to search for meaning down to the last word

The day – that the melody of every word be Life

and I won’t be suffering to find the right rhythm for every last poem

.

That day – when every lip is a song

and the least song will be a kiss

That day – when you come – when you’ll come forever –

and Kindness be equal to Beauty

.

The day – that we toss seeds to the doves…

and I await that day

even if upon that day I myself no longer be.

. . . . .

We are grateful to Hassan H. Faramarz for the Persian-to-English translation of “Bright Horizon”.

What did Jesus mean by: “Blessed are the poor in spirit for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” ? A Poet’s Interpretation…

Posted: March 29, 2013 Filed under: Alice Walker, English | Tags: Easter poems Comments Off on What did Jesus mean by: “Blessed are the poor in spirit for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” ? A Poet’s Interpretation…Alice Walker (born 1944, Eatonton, Georgia, U.S.A.)

“Blessed are the poor in spirit (for theirs is the kingdom of heaven)”

.

Did you ever understand this?

If my spirit was poor, how could I enter heaven?

Was I depressed?

Understanding editing,

I see how a comma, removed or inserted

with careful plan,

can change everything.

I was reminded of this

when a poor young man

in Tunisia

desperate to live

and humiliated for trying

set himself ablaze;

I felt uncomfortably warm

as if scalded by his shame.

I do not have to sell vegetables from a cart as he did

or live in narrow rooms too small for spacious thought;

and, at this late date,

I do not worry that someone will

remove every single opportunity

for me to thrive.

Still, I am connected to, inseparable from,

this young man.

Blessed are the poor, in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven – Jesus.

(Commas restored).

Jesus was, as usual, talking about solidarity: about how we join with

others

and, in spirit, feel the world, and suffering, the same as them.

This is the kingdom of owning the other as self, the self as other;

that transforms grief into

peace and delight.

I, and you, might enter the heaven

of right here

through this door.

In this spirit, knowing we are blessed,

we might remain poor.

.

© 2011, Alice Walker

.

“Blessed are the poor in spirit for theirs is the kingdom of heaven”

is quoted from the Book of Matthew, Chapter 5, verse 3, in The Bible.

. . .

Alice Walker is a Pulitzer-Prize-winning novelist, short-story writer, poet and activist. Earlier this month Walker was interviewed for The Observer Magazine by Alex Clark. Walker told her:

“In each of us, there is a little voice that knows exactly which way to go. And I learned very early to listen to it…”

. . .

Photographs:

Ethiopia, 1985 – Sebastião Salgado

Tulelake, California, 1930s – Family on the road – Dorothea Lange

Germany, 1930 – Gypsy man – August Sander

Germany, late 1920s – Beggar – August Sander

Russia, around 1920 – Beggar with lyra – Nikolai Svischev-Paola

Oklahoma, U.S.A., 1914 – Old couple, sharecroppers – photographer unknown

Al-Ma’arri: the poet as religious sceptic

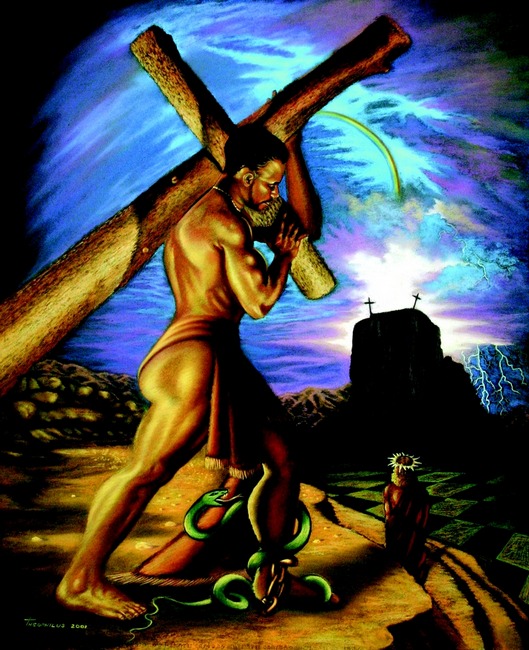

Posted: March 29, 2013 Filed under: Al-Ma'arri, English Comments Off on Al-Ma’arri: the poet as religious sceptic “Champion of the World”, a painting by Brian Whelan, 2011. Jesus to the left, Beelzebub on the right, and God-the-Referee – centre!

“Champion of the World”, a painting by Brian Whelan, 2011. Jesus to the left, Beelzebub on the right, and God-the-Referee – centre!

.

Al-Ma’arri (Ma’arri, Syria, 973-1058)

.

Whenever man from speech refrains, his foes are few,

Even though he’s stricken down by fortune and falls low.

Silently the flea sips up its fill of human blood,

Thus making less the heinousness of its sin:

It follows not the way parched mosquitoes go,

Trumpeting with high-trilled note, you smarting all the while.

If an insolent man thrusts a sword of speech against you,

Oppose him with your patience, so you may break its edge.

…..

The body, which gives you during life a form,

Is but your vase: be not deceived, my soul!

Cheap is the bowl for storing honey in,

But precious for the contents of the bowl.

…..

We laugh, but inept is our laughter,

We should weep, and weep sore,

Who are shattered like glass and thereafter

Remolded no more.

…..

Two fates still hold us fast,

A future and a past;

Two vessels’ vast embrace

Surrounds us—time and space.

And when we ask what end

Our Maker did intend,

Some answering voice is heard

That utters no plain word.

…..

You said, “A wise one created us”;

That may be true, we would agree.

“Outside of time and space,” you postulated.

Then why not say at once that you

Propound a mystery immense

Which tells us of our lack of sense?

…..

They all err—Muslims, Jews,

Christians, and Zoroastrians:

Humanity follows two world-wide sects:

One, man intelligent without religion,

The second, religious without intellect.

…..

So, too, the creeds of man: the one prevails

Until the other comes; and this one fails

When that one triumphs; ah, the lonesome world

Will always want the latest fairy tales.

…..

There was a time when I was fain to guess

The riddles of our life, when I would soar

Against the cruel secrets of the door,

So that I fell to deeper loneliness.

.

(Translation from Arabic: Henry Baerlein, 1909)

…..

Live well! Be wary of this life, I say;

Do not o’erload yourself with righteousness.

Behold! the sword we polish in excess,

We gradually polish it away.

.

(Translation from Arabic: Henry Baerlein, 1909)

…..

What is religion? A maid kept close that no eye may view her;

The price of her wedding gifts and dowry baffles the wooer.

Of all the goodly doctrine that I from the pulpit heard

My heart has never accepted so much as a single word.

…..

Traditions come from the past, of high import if they be true;

Ah, but weak is the chain of those who warrant their truth.

Consult thy reason and let perdition take others all:

Of all the conference Reason best will counsel and guide.

A little doubt is better than total credulity.

. . .

Translations* from Arabic into English: Reynold Alleyne Nicholson (1868-1945)

*Except for two poems translated by Henry Baerlein

. . .

Al-Ma’arri (973-1058), whose full name was Abū al-ʿAlāʾ al-Maʿarrī, (in Arabic: أبو العلاء أحمد بن عبد الله بن سليمان التنوخي المعري ) was born in Ma’arra, Syria. He was a poet of common sense, a rationalist, a reasonable sceptic – and yet a pious man, too. Are his poems heretical? To some, yes. Yet he wrote his Truth. Not until the Enlightenment in the 18th century would such confident scepticism in Western thought arise again among poets and writers. Al-Ma’arri’s sarcasm was egalitarian; Judaism, Christianity, and his own Islam all got from him a good tongue-lashing. Reason he valued – above “tradition” or “revelation”. Al-Ma’arri’s writings put us in mind of Xenophanes of Colophon, Lucretius, and the Cārvāka philosophers of India – all of whom were sharp minds that pierced beyond received Wisdom.

. . .

“Yo cumplo mi encuentro con La Vida” / “I keep Life’s rendezvous”: Poemas para Viernes Santo / Good Friday poems: Countee Cullen

Posted: March 29, 2013 Filed under: Countee Cullen, English, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: Black poets, Good Friday poems, Poemas para Viernes Santo, Poetas negros Comments Off on “Yo cumplo mi encuentro con La Vida” / “I keep Life’s rendezvous”: Poemas para Viernes Santo / Good Friday poems: Countee Cullen

Countee Cullen (Poeta negro del “Renacimiento de Harlem”, E.E.U.U., 1903-1946)

“Habla Simón de Cirene”

.

Nunca me habló ninguna palabra

pero me llamó por mi nombre;

No me habló por señas,

y aún entendí y vine.

.

Al princípio dije, “No cargaré

sobre mi espalda Su cruz;

Sólo procura colocarla allá

porque es negra mi piel.”

.

Pero Él moría por un sueño,

Y Él estuvo muy dócil,

Y en Sus ojos hubo un resplandor

que los hombres viajarán lejos para buscar.

.

Él – el mismo – ganó mi piedad;

Yo hice solamente por Cristo

Lo que todo el Imperio romano no pudo forjar en mí

con moretón de látigo o de piedra.

. . .

Countee Cullen (1903-1946)

“Simon the Cyrenian Speaks”

.

He never spoke a word to me,

And yet He called my name;

He never gave a sign to me,

And yet I knew and came.

At first I said, “I will not bear

His cross upon my back;

He only seeks to place it there

Because my skin is black.”

But He was dying for a dream,

And He was very meek,

And in His eyes there shone a gleam

Men journey far to seek.

It was Himself my pity bought;

I did for Christ alone

What all of Rome could not have wrought

With bruise of lash or stone.

.

Luke 23:26

“And as they led Him away, they laid hold upon one Simon, a Cyrenian, coming out of the country,

and on him they laid the cross, that he might bear it after Jesus”.

. . .

“Tengo un encuentro con La Vida”

.

Tengo un encuentro con La Vida,

durante los días que pasen,

antes de que pasen como un bólido mi juventud y mi fuerza de mente,

antes de que las dulces voces se vuelvan mudas.

.

Tengo un ‘rendez-vous’ con Esta Vida.

cuando canturrean los primeros heraldos de la Primavera.

Por seguro hay gente que gritaría que sea tanto mejor

coronar los días con reposo en vez de

enfrentar el camino, el viento, la lluvia

– para poner oídos al llamado profundo.

.

No tengo miedo ni de la lluvia, del viento, ni del camino abierto,

pero aún tengo, ay, tan mucho miedo, también,

por temor de que La Muerte me conozca y me requiera antes de que

yo cumpla mi ‘rendez-vous’ con La Vida.

. . .

“I have a rendezvous with Life”

.

I have a rendezvous with Life,

In days I hope will come,

Ere youth has sped, and strength of mind,

Ere voices sweet grow dumb.

I have a rendezvous with Life,

When Spring’s first heralds hum.

Sure some would cry it’s better far

To crown their days with sleep

Than face the road, the wind and rain,

To heed the calling deep.

Though wet nor blow nor space I fear,

Yet fear I deeply, too,

Lest Death should meet and claim me ere

I keep Life’s rendezvous.

. . .

Countee Cullen produced most of his famous poems between 1923 and 1929; he was at the top of his form from the end of his teens through his 20s – very early for a good poet.

His poems “Heritage”, “Yet Do I Marvel”, “The Ballad of the Brown Girl”, and “The Black Christ” are classics of The Harlem Renaissance. We feature here two of Cullen’s lesser-known poems

– including Spanish translations.

. . . . .

Traducciones del inglés al español: Alexander Best

“The Last Supper or: From now on, the worms speak for him” / “La Última Cena”

Posted: March 29, 2013 Filed under: English, Mario Meléndez, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on “The Last Supper or: From now on, the worms speak for him” / “La Última Cena”Mario Meléndez (nace/born 1971, Chile)

“La Última Cena” / “The Last Supper or: From now on, the worms speak for him”

.

Y el gusano mordió mi cuerpo

y dando gracias

lo repartió entre los suyos diciendo

“Hermanos

éste es el cuerpo de un poeta

tomad y comed todos de él

pero hacedlo con respeto

cuidad de no dañar sus cabellos

o sus ojos o sus labios

los guardaremos como reliquia

y cobraremos entrada por verlos”.

.

And the worm bit into my body

and, giving thanks,

divided it among his brethren, saying:

“Brothers,

this is the body of a poet

– take it, eat all of it,

but do this with respect,

careful not to harm the hair upon his head,

or his eyes, or his lips

– we will keep those as sacred relics

and we’ll charge an entry fee for people to see them.”

.

Mientras esto ocurría

algunos arreglaban las flores

otros medían la hondura de la fosa

y los más osados insultaban a los deudos

o simplemente dormían a la sombra de un espino.

.

While this was going on

some were arranging flowers,

others were gauging the depth of the grave,

and the boldest ones were busy offending the relatives and mourners

– or merely sleeping ‘neath the shade of a hawthorn tree.

.

Pero una vez acabado el banquete

el mismo gusano tomó mi sangre

y dando gracias también

la repartió entre los suyos diciendo

“Hermanos

ésta es la sangre de un poeta

sangre que será entregada a vosotros

para el regocijo de vuestras almas

bebamos todos hasta caer borrachos

y recuerden

el último en quedar de pie

reunirá los restos del difunto”.

.

But once the banquet was finished

the same worm drank my blood

and, also giving thanks,

shared my blood among the rest of those present,

saying:

“Brothers,

this is the blood of a poet,

blood consecrated for you

for the sake of your souls’ rejoicing

– drink all of it until you fall down drunk,

that you may remember:

in high heaven it’s a stubborn fact –

you will be reunited with the remains of the deceased.”

.

Y el último en quedar de pie

no solamente reunió los restos del difunto

los ojos, los labios, los cabellos

y una parte apreciable del estómago

y los muslos que no fueron devorados

junto con las ropas

y uno que otro objeto de valor

sino que además escribió con sangre

con la misma sangre derramada

escribió sobre la lápida

“Aquí yace Mario Meléndez

un poeta

las palabras no vinieron a despedirlo

desde ahora los gusanos hablaremos por él”.

.

And the last-gasp fact…

not only was it the ‘joining-together’ of all of them

with the remains of the deceased –

his eyes, his lips, the hair upon his head,

an appreciable part of his stomach,

the thighs which were not devoured,

together with his clothing

and one or another item of value –

but that, moreover,

it was written in blood – that same spilt blood –

he wrote upon his own headstone:

“Here lies Mario Meléndez, a poet.

Words never came to bid him farewell,

and from now on,

the worms speak for him.”

.

Traducción/interpretación en inglés: Alexander Best

. . .

Mario Meléndez studied journalism at La República University in Santiago, Chile. In 1993 – the bicentennial of Linares – he won that city’s Municipal Prize for Literature. In 2003, in Rome, he was made an honorary member of the Academy of European Culture, after speaking at the First International Gathering for Amnesty and Solidarity of The People. In 2005 he won the Harvest International Prize for best poem in Spanish from the University of California Polytechnic.

Alan Clark: “Guerrero and Heart’s Blood” / “Guerrero y Sangre del Corazón”

Posted: March 19, 2013 Filed under: Alan Clark, English, Spanish Comments Off on Alan Clark: “Guerrero and Heart’s Blood” / “Guerrero y Sangre del Corazón”Un extracto en cinco voces – de “Guerrero y Sangre del Corazón” por Alan Clark:

.

Guerrero habla:

“Yo soy Gonzalo Guerrero, Capitán al servicio de Nachancán, Señor de Chetumal. Casado. Un padre. Cortado y cubierto de cicatrices y decorado con tintes. Un guerrero conocido entre mi gente como “hombre valiente”.

Yo no soy aquel que fui. En Palos, donde nací, mi anterior familia vive todavia, a menos que haya habido una plaga o una guerra. Mi padre y mi madre quizás vivan aún. Pero lo dudo.

Había un árbol alto junto a la vieja casa, al que mi hermano Rodrigo y yo solíamos atar una soga, que dejábamos caer al suelo, luego trepábamos hasta lo más delgado del tronco y -pas!- soltábamos la cuerda y volábamos en el cielo cálido y azul entre el estruendo de las hojas. Les hacíamos jugarretas.

A nuestras hermanas, las espíabamos cuando se bañaban, y detestábamos la escuela y al cura de la iglesia, que nos pegaba en el nombre de Dios.

Ahora estoy muy lejos de todo eso. Soy algo así como un noble, y jefe en tiempo de guerra. Ahora escucho mensajes en el humo de papeles ensangrentados que los sacerdotes encienden en la cima de los templos, papeles empapados en la sangre de sus propios miembros desgarrados. A veces la sangre es mía. Me toca oficiar cuando se hace un sacrificio, y sentir como los cielos y la tierra cambian y se estremecen y se reconstruyen a sí mismos con el advenimiento de la más suprema de las ofrendas sagradas. Como un pequeño trozo del esclavo, del niño, o del cautivo, que quizás yo mismo haya sometido con estas manos. Su terror anticipa el temblor aún mayor del mundo una vez que hayamos cortado y ofrendado y ungido. Me tomó mucho tiempo vencer mi propio terror y repulsión.

El gran Señor Nachancán, quien me tomó luego que escapé de su espantoso vecino y enemigo, vió en mi lo que quizás yo nunca hubiese visto por mi mismo. Me dijo que de una sola mirada, cuando fui llevado ante él, consumido y cubierto con mis andrajos de esclavo, supo mi lugar en los cielo, a pesar de mi apariencia. Incluyendo mi negra barba crecida y despareja.

. . .

Habla Nachancán:

“Ja. Las noticias sobre los extranjeros habían llegado a mí aún antes de que desembarcaran. Mis mensajeros esparcieron las nuevas. Lo recuerdo bien. Conejo Dos pidió las jaulas y los postes. Kinich Ek quería a las dos mujeres. Le dimos una. Le arrancaron el corazón antes de terminar el día, como a los otros tres. Yo tomé una, para que ayudara a mi esposa y para interrogarla. Hace ya un año que murió. Mi mujer es muy dura con sus esclavos. Pero los alimenta bien.

Eran un grupo raro. Les arrancamos sus andrajos impregnados de sal para ver si eran humanos, como nosotros. Nuestros magos y sacerdotes los atormentaban y les lanzaron hechizos de humo. Eran hombres, pero blancos y peludos. Y hablaban un idioma que no pudimos entender, y temblaban en el calor, implorándonos por señas que les diéramos agua y comida. Los pusimos en jaulas para que engordaran. No sabían mal, cocidos con chiles. Nada mal…

Sólo quise uno para mí. Fue primero con Conejo, que es cruel y estúpido, hasta que un día huyó y vino a mí. Desde el primer momento vi en él a alguien de provecho, alguien para nosotros. Mi lengua se adelantó a mi voluntad: dénmelo.

.

Habla Nachancán:

Extraño pocas cosas. Mi naturaleza es afable como esta sonrisa que ven. Y la risa siempre a flor de labios – lo que a veces ha hecho pensar a mis enemigos que estoy loco…sus cabezas no sonríen desde donde nos miran, sobre los escalones del templo. Pronto sus ceños fruncidos desaparecerán. Y entonces las moscas se reirán para mí.

Cuando llegó, el extranjero Guerrero, noté que su presencia alteraba mucho a mi hija, Mucuy, que le lanzó una mirada de odio, y luego le ignoró. Cuando llegó la siguiente oportunidad de sangrarme, pedí a los dioses que me dieran su respaldo. Las serpientes no dicen más que lo necesario.

. . .

Aguilar habla:

¿Y dónde está la maldita gloria para el que va a morir? Esta noche se van a llevar a uno de mis pupilos a la piedra. Su nombre es Pop Che. Durante semanas he estado llevándole agua y comida. Pero no quería comer. ¿Puede alguien culparlo? Y, oh Dios, sólo es un muchachito. Un granjero que un día se puso su camisa de algodón, desenpolvó su lanza, se puso algunas plumas en el pelo –y dejó a su mujer, a sus hijos, y a su anciana madre, para ir a pelear contra Nachancán y los soldados perdidos de Guerrero. Y ahora está aquí con nosotros. Todo mi coraje es inútil. ¿Y qué han logrado todas mis plegarias por él? Le darán la bebida, lo pintarán, y…

.

Pero ¡ay!, la sangre de mi corazón se va con él. Qué puedo hacer más que seguir rezando y llevarle más agua. ¿Decirle que el dios que ni siquiera acepta lo espera en los cielos para tomarlo en sus brazos celestiales? Ya vienen. Los tambores han comenzado a sonar. Ay, ese sonido me llega como si me golpeasen a mí. Estoy asqueado y harto de todo.

.

Aguilar habla:

No es tan malo ser esclavo. No es tan malo estar vestido con harapos desechados, ser pateado e insultado y golpeado hasta morir por gente perdida en supersticiones. Y admite que hay cierto arte en lo que hacen, y a veces gran belleza en sus vestidos tejidos, y en sus vasijas de barro pintado. Inclusive en el brillante decorado de las piedras y del oro con los que se adornan, y con los que a veces se perforan grotescamente. Sus canciones y cantos, el embrujo de los tambores y las flautas, las trompetas y las caracolas. No soy ciego ni sordo a estas cosas. ¡Pero sus dioses me consternan, representan el horror del deseo de sangre del demonio, y en el momento del sacrificio quisiera aullar, conjurar la venganza de Dios para que desmenuzara hasta hacerlos polvo estos templos blanqueados de cal y manchados de sangre! Dios salve nuestras almas.

. . .

Alicia habla:

¡Gonzalo! ¡Gonzalo! Los viejos ojos de tu madre están puestos en ti. Dondequiera que estés, estos ojos te acompañan. Hoy me puse a quemar algunas ramas del viejo árbol que da las naranjas que tanto te gustaban. Esas ramas ya están viejas y secas porque hace ya tanto que te fuiste. ¿Para siempre? Y porque tu padre ha muerto. Murió la muerte rápida y fea de la plaga –su lengua estaba negra y gruesa, se ahogaba- y no podía decir tu nombre. Tu hermano y tus hermanas están bien. Eres tío de una horda de niños.

Gonzalo. Por el amor que te tengo, te entiendo y te veo, dondequiera que estés. En las cavernas de tu corazón, en el poder de tus brazos y de tu mente, siempre me he maravillado. Tal como ahora que sueño y te veo. Y no me preocupo, sólo te extraño. ¿Será que te has ido para siempre de tu hogar, de nosotros? En donde tu padre te engendró de la pasión por su madre, que te trajo con alegría y dolor, mi primer hijo. Mi amor por ti, buen hijo errante, jamás ha mermado, ni lo hará jamás, aún después de nuestra muerte terrenal. Y ahora, para verte, sólo me queda esperar ese día, porque estos viejos ojos ya no lo ven todo.

Con esta vieja mano alzo una naranja al sol, y huelo en el humo que se levanta de las viejas ramas de tu árbol favorito, el sabor de la fruta que aún perdura en él. Y con las cenizas que queden, abonaré mi jardín en tu nombre. Buen hijo.

. . .

Mucuy habla:

Acerca tuyo, esposo mío, déjame hablar. Tu fértil esposa ha yacido despierta junto a ti muchas noches, sintiéndose feliz y afortunada. Que al principio no podía entender. Tu eras un extraño, y –casi- parecías un animal. Tu cuerpo enfermo y pálido, tus mejillas cubiertas de pelo, y tu hablar rápido y extraño, me descorazonaba. Cuando me miraste por primera vez, me estremecí y sentí que gritaba por dentro, así que le pedí a mi madre que me explicara porque me causabas tanta confusión, que me dijera qué y quién eras, un hombre que daba tan mala impresión en todo. Si bien uno del que mi padre se expresó como si fuese su propio hijo. Pero finalmente el amor se reveló en mi corazón. Y te encontré esperándome como el sol cuando llueve, y crecí, y aprendí que nuestras caricias arrojaban una luz secreta mientras la luna aguardaba en su oscuro mundo para brillar sobre lo que surgiera. En ti encuentro, dentro de mis más ardientes deseos y mi famoso carácter, toda la suavidad y el peligro que toda mujer anhela, y escuché tus palabras que vagaban como los inseguros pasos de la niñez hacia mí, y temblé al sentir como te arrimabas a mí como las aguas del mar de Cozumel, que llegan a azotar día y noche, como el temblor de mis nervios mientras me preparo a mi festín de ti, con mis lenguas y dientes deseando tu sabor.

.

Así he llegado a conocerte, y de ello nació esta mujer fuerte, que en su pasión nutre la vida de toda su gente… porque antes sólo era buena para esperar, hasta que el mar te arrojó de quien sabe donde, más allá de donde los soles salen para alumbrar los días. Tu viniste de algún otro lugar, de donde te enviaron los dioses y las diosas.

.

Mucuy habla de su intimidad con Guerrero:

Ay, tu lengua tropezando y enredándose con la mía, pareciera haberse convertido en aquella con la que naciste. Te veo caminar entre los hombres, algunos de ellos hermanos míos, los mejores hijos de Nachancán y de la madre que tengo la bendición de poder ver

todos los días, y veo que tú eres uno de nosotros tanto como es posible, y por eso perdono tan fácilmente tus cuestionamientos, tus sueños, mi apetito nocturno, para ayudar a revelarte, mientras los años se desenredan en nuestros cuerpos acostados, o caminando entrelazados tal como nuestros espíritus lo están, y entender tus necesidades antes que tú mismo. Hemos susurrado mucho más allá del tiempo en que los pájaros se van a dormir acurrucándose en sus alas, sobre el misterio de cómo llegamos a ser uno.

.

Mucuy habla sobre la necesidad de que Guerrero participe en los sacrificios:

¿Acaso no soy, querido esposo, padre de mi hija e hijos, también tu maestra en las cosas que tanto te hacen temblar? Al fin ascenderás las escaleras del templo, y te infligirás las heridas que sangren y alimenten los fuegos de lo que verás, las cosas que ves tú mucho más claramente que yo, que te digo: mi tierno y sobrecogedor hombre –¡ve con papá Nachancán y con Pool, y los demás, esta noche, y sé un hombre! Nadie espera que puedas saber qué tanto dependen de ti este ritual y esta vida, aunque me hayas dicho que va contra tu formación. Sé valiente, mi querido esposo, y conoce la sangre que se derramará sobre ti; saboréala si puedes. El muchacho nació para esto. Su corazón fue medido desde el comienzo del mundo –para esto. El dios cuyos días han vuelto a llegar, ha hablado, y mantiene unidas las piedras sobre las que reposa –para esto. Espera que nuestros ojos se glorifiquen en estas muertes –por él. Para que nosotros en él lo veamos y honremos.

.

Traducción del inglés al español: Lisa Primus

. . .

Gonzalo Guerrero (1470-1536) fue un marino español y uno de los primeros europeos que vivió en el seno de una sociedad indígena. Murió luchando contra los conquistadores españoles. Guerrero es un personaje porfiado porque se aculturó al punto de ser un jefe maya durante la conquista de Yucatán. En México se refieren a él como Padre del Mestizaje. Presentamos aquí la obra del escritor y pintor Alan Clark – “Guerrero and Heart’s Blood /Guerrero y Sangre del Corazón” (Henning Bartsch, México, D. F., 1999) con la traducción de Lisa Primus.

An excerpt in five voices – from “Guerrero and Heart’s Blood” by Alan Clark:

.

Guerrero speaks:

I am Gonzalo Guerrero, Captain in the service of Nachancan, Lord of Chektumal. Married. A father. Cut and scarred and decorated with inks. A warrior, who is known among my people as a “brave man”.

.

I am no more what I used to be. In Palos, where I was born, my old family still lives. Unless there’s been a plague, or a war. My father and mother may still be alive, my brothers and sisters who I played with, and tormented. Maybe nothing has changed. Maybe everything. But I doubt that.

.

There was tall tree by our old house, my brother Rodrigo and I would tie a rope to, then pull it down to the ground, climb onto its thin trunk, and snap! Let the rope go and fly into the hot blue air in a clamor of leaves. We played tricks on our sisters, spied on them in their baths when we were all older. And hated the fathers of the church, who beat us in the name of God.

.

Now I’m far away from all of that. I am a kind of lord myself, and a chief in time of war. Now I harken to the messages in the smoke of blood stained papers the priests ignite on the temple tops. Papers drenched in their own blood, from their own shredded members. Sometimes the blood is my own. I am in attendance when a sacrifice is made, and feel the earth and the skies change and quiver and recast themselves at the advent of this most supreme offering. I eat some small piece of the slave or the child or the captive I myself, with these same hands, may have subdued. Their terror anticipates the wide world’s trembling when we have cut and offered and anointed. It took a long time to get past my own terror and revulsion.

.

The great Lord Nachancan, who took me in after I had escaped from his horrific neighbor and enemy, saw in me what I had perhaps would never have seen, myself. He told me that from one look, as I was brought before him, worn out, in my slave’s rags, he knew my place in the heavens and was undeceived by my appearance otherwise. Even by my ragged, black beard.

. . .

Nachancan speaks:

Ha. The word about the strangers was in my ear before they landed. My messengers had run with the news. I remember it well. Two Rabbit called for the cages and the long poles. Kinich Ek wanted the two women. We gave him one. Her heart was out before the day ended. The other I took to help my wife, and to question. It was only a year ago she died. My wife works her slaves very hard. But feeds them well.

.

They were a strange crew. We stripped them of their salty rags to see if they were human, like ourselves. Our priest and magician poked them all over and spelled them with smokes. They were men, but white and hairy, and spoke in a tongue we didn’t understand. They shivered in the heat, begging us by signs for food and drink. We put them into the cages. They did not taste too bad, cooked with chilies. Not too bad…

.

Only one I wanted for myself. He went first to Rabbit, who is stupid and cruel, until the day he ran to me. From the first, I saw him as someone of use, someone for us. My tongue spoke out ahead of me: Give me him.

.

There is little I miss. My nature is this smile you see, and the laughter that brims in my blood. Which has sometimes made my enemies think I am a fool. Their heads don’t smile from where they stare out on the temple steps. Soon enough their sagging frowns are gone, and then the buzzards make a laughing sign to me.

.

When he came, the stranger, Guerrero, I could see the sight of him upset too much my daughter, Mucuy. She glowered and shot an arrow from her eyes, and then would look no more. When I next bled myself, I asked the gods to second me in what I’d seen. The serpent speaks no more than we can know.

. . .

Aguilar speaks:

And where is the glory for the one who’s going to die? They’re taking a ward of mine up to the stone tonight. His name is Pop Che. For weeks I’ve brought him his food and water. But he won’t eat. Can you blame him? And, O God, he’s only a little man, a farmer who put on his cotton shirt one day, and dusted off his spear, left his wife and his children, and old mother, to go fight against Nachancan and the lost Guerrero’s soldiers.

.

And now he’s here with us. All my raging is useless. What have my prayers for him accomplished? They’ll give him the drink, paint him and feather him, and then….

.

But O! my heart’s blood goes with him. What else can I do? Tell him that the God he doesn’t even want, is waiting in heaven to hold him in his heavenly arms?

.

Here they come. The drums have started. Ah! That sound pounds into me as if it was me they were striking. I am sick and weak with everything.

.

It is not so bad, to be a slave. It is not so bad to be dressed in rags, to be kicked and insulted and worked almost to death by people lost in their superstitions. I will even admit there’s a certain art in what they do, and sometimes great beauty in their woven cloths, in their painted earthenwares. Even in the glittering ornateness of the stones and gold with which they adorn themselves. And are sometimes pierced to grotesqueness by!

.

I am not blind and deaf to these things. But their gods dismay me, are the horror of the Devil’s own wish for blood. And at the moment of sacrifice, I want to howl! and call God’s vengeance down to crumble to dust these whitewashed and bloodstained temples. God save all our souls…

. . .

Alicia speaks:

Gonzalo. Gonzalo. Your mother’s eyes are on you. Wherever you are, these eyes are on you. Today I’m burning some branches from the old tree that bears the fruit, the oranges you love, branches old and dry now because you’ve been gone so long. Forever?

.

Your father is dead. He died the fast and ugly death of plague, and couldn’t even speak your name. Your brothers and sister are well. You are now the uncle to a horde of growing kin.

.

Gonzalo. In my love for you, I understand and see you, wherever you may be. Of the passions of your heart, of the power of your arms and mind, I have always been in wonderment. This is no less so this hour I dream and see you. O, and I do not worry, but only miss you so! Forever gone from us and this, your home? Where your father seeded you in passion with his wife, who bore you happily in pain. My first born child.

.

My love for you, good son and wanderer, has never ceased, nor will it ever, even beyond our earthly dying. And now I only wait to see you then, because these old eyes cannot see everything they wish to.

.

With this hand I lift an orange to the sun, and smell in the smoke that rises from the worn out branches of your favorite tree, the savor of the fruit that lived within. And with the ashes left, will feed my garden in your name. Good son.

. . .

Mucuy speaks:

About you, my husband, let me speak. Your fertile wife has lain awake beside you many nights, and felt a wonder at her fortune. Which at first she could not feel. You were a stranger, almost, it seemed, a beast. Your body was sick and pale, your cheeks filled with hair, your strange, fast words dismaying me. When you first looked at me, I shivered and grew shrill, and asked my mother to explain the confusions you provoked, to tell me who and what you were, a man so alrogether wrong. But one of whom my father spoke as if you were a son.

.

But then my love unclouded in my heart. I found you waiting there for me like sun and summer rain. And I grew, and knew our touches cast in secret lightness while the moon was waiting in her darkest world to shine on what would be.

.

I found in you, inside my fiercest wish and famous temper, all my softness, and the danger any woman wants. And listened to your words, which wandered like the hesitating steps of childhood toward me, and trembled for the way you washed against me, like the waters of the sea off Cozumel, coming in to thunder day and night, like the trembling of my nerves as I’m edging toward my feast of you, whose taste my tongues and teeth desire.

.

Like this, I’ve come to know you, and out of this become the woman who is strong, and in her passion feeds the life of all her people. Because before, I was only great in waiting – when you washed ashore from nowhere, from somewhere out beyond where all the suns rise up to gleam awake the days. From somewhere else you came, the goddesses and gods had sent you.

.

And O, your stumbling tongue in tangling with my own, has since become as if it was the one you hatched with. I watch you walk among the men, some of them my brothers, the strongest sons of Nachancan, and the mother who I live in blessedness to see each day, and know that you are one of us as much as you can be, your dreams my nightly appetite to help explain to you, as the years unravel in our bodies lying down, or walking braided as our spirits are, and understand your needs before you do yourself. We’ve whispered long past the hour the birds have gone to sleep inside their wings, about the mystery of why we came to be as one.

.

Mucuy speaks about his need to attend the sacrifices:

Am I not, dear husband, father of my daughter and sons, also yet your teacher in the things that make you tremble so? At last! To climb the temple steps and prick upon yourself the wound that bleeds, and feeds the fire of what you’ll see there, the things you see so much more than I!

.

Who say to you, my tender, overwhelming man: Go to, with father Nachancan, and Pool, and the others on this night and be a man! No one expects that you can know how much this ritual, how much this life depends on you, you have told me goes against your way. Be brave, my darling husband, and know the blood that will spatter onto you, and taste it if you can. The boy is born for this. His heart is measured since the world began, for this. The God whose day has come around again, has spoken, and commands the stones themselves he rests upon, to worship him.

. . . . .

Alan Clark writes:

Gonzalo Guerrero (1470-1536) was a sailor from Palos de la Frontera, Spain, and was shipwrecked around 1511 while sailing from Panama to Santo Domingo with a dozen or so others. They drifted for a couple of weeks before Caribbean currents brought them to the shores of what is now the State of Quintana Roo in modern-day México where they were captured by Maya people and put into cages. Eight years later when Hernán Córtes arrived at Kùutsmil (Cozumel ) to begin what would be the Conquest of México, there were only two from this shipwreck still alive – Guerrero, and a priest named Jerónimo de Aguilar. Guerrero was by this time married with children, the first mestizos in México, and was a chief in time of war for the Maya lord Nachancán. Aguilar was a slave living in another city state.

.

I’ve attempted, through Guerrero’s wife, Mucuy – and through Nachancán, Aguilar, Guerrero’s mother in Spain (whom I’ve called Alicia), and of course through Guerrero himself – to give both the inner and outer picture/story of this man, a people, and the times in which they lived.

.

Guerrero and Heart’s Blood was published in 1999 by Henning Bartsch, México City. Although I never had the theatre in mind when I was writing it, Guerrero has had a variety of stagings in both the U.S.A. and México. Heart’s Blood is an accompanying story, told by Aguilar, and was performed in both Spanish and English in México as an adapted monologue by Alejandro Reza, with a score for cello by Vincent Carver Luke. The translation into Spanish is by Lisa Primus. My painting, on the cover of the original book, is called “Blood and Stone”.

. . . . .

Poems for Saint Patrick’s Day: favourites of “me Ma”

Posted: March 17, 2013 Filed under: Eavan Boland, English | Tags: Poems for Saint Patrick's Day Comments Off on Poems for Saint Patrick’s Day: favourites of “me Ma”

ZP_Eileen Thompson in 1948, not long after her arrival in Toronto from Belfast, Northern Ireland_Now in her 80s she is an avid reader – still – and she has chosen the two poems we feature here.

“Donal Og” / “Young Donald”

(from an old Irish Gaelic ballad, probably composed in the 10th century)

Translation by Augusta, Lady Gregory (1852-1932)

.

It is late last night the dog was speaking of you;

the snipe was speaking of you in her deep marsh.

It is you are the lonely bird through the woods;

and that you may be without a mate until you find me.

.

You promised me, and you said a lie to me,

that you would be before me where the sheep are flocked;

I gave a whistle and three hundred cries to you,

and I found nothing there but a bleating lamb.

.

You promised me a thing that was hard for you,

a ship of gold under a silver mast;

twelve towns with a market in all of them,

and a fine white court by the side of the sea.

.

You promised me a thing that is not possible,

that you would give me gloves of the skin of a fish;

that you would give me shoes of the skin of a bird;

and a suit of the dearest silk in Ireland.

.

When I go by myself to the Well of Loneliness,

I sit down and I go through my trouble;

when I see the world and do not see my boy,

he that has an amber shade in his hair.

.

It was on that Sunday I gave my love to you;

the Sunday that is last before Easter Sunday.

And myself on my knees reading the Passion;

and my two eyes giving love to you for ever.

.

My mother said to me not to be talking with you today,

or tomorrow, or on the Sunday;

it was a bad time she took for telling me that;

it was shutting the door after the house was robbed.

.

My heart is as black as the blackness of the sloe,

or as the black coal that is on the smith’s forge;

or as the sole of a shoe left in white halls;

it was you that put that darkness over my life.

.

You have taken the east from me; you have taken the west from me;

you have taken what is before me and what is behind me;

you have taken the moon, you have taken the sun from me;

and my fear is great that you have taken God from me!

Eavan Boland (born 1944, Dublin)

“Quarantine”

.

In the worst hour of the worst season

of the worst year of a whole people

a man set out from the workhouse with his wife.

He was walking – they were both walking – north.

.

She was sick with famine fever and could not keep up.

He lifted her and put her on his back.

He walked like that west and west and north.

Until at nightfall under freezing stars they arrived.

.

In the morning they were both found dead.

Of cold. Of hunger. Of the toxins of a whole history.

But her feet were held against his breastbone.

The last heat of his flesh was his last gift to her.

.

Let no love poem ever come to this threshold.

There is no place here for the inexact

praise of the easy graces and sensuality of the body.

There is only time for this merciless inventory:

.

Their death together in the winter of 1847.

Also what they suffered. How they lived.

And what there is between a man and woman.

And in which darkness it can best be proved.

. . . . .

ZP_The Jubilant Man, a sculpture by Rowan Gillespie at Ireland Park in Toronto_The Irish Potato Famine, known as An Gorta Mór or The Great Hunger, occurred between 1845 and 1852. 30,000 forced-out or fleeing Irish arrived in Toronto during 1847 alone – their numbers being greater than the actual population of Toronto at the time.

Poems for Saint Patrick’s Day: Jenkinson, Davitt, Ó Searcaigh, Ní Dhomhnaill

Posted: March 17, 2013 Filed under: English, Irish | Tags: Poems for Saint Patrick's Day Comments Off on Poems for Saint Patrick’s Day: Jenkinson, Davitt, Ó Searcaigh, Ní DhomhnaillBiddy Jenkinson (born 1949)

“Cruit Dhubhrois”

.

Bruith do laidhre im théada ceoil

ag corraíl fós, a chruitire,

clingeadh nóna ar crith go fóill

im chéis is an oíche ag ceiliúradh.

.

Oíche thláith, gan siolla aeir,

a ghabhann chuici sinechrith

mo shreangán nó go dtéann falsaer

grá mar rithí ceoil faoin mbith,

.

Go gcroitheann criogar a thiompán,

go gcnagann cosa briosca míl,

go sioscann fionnadh liath leamhain,

go bpleancann damhán téada a lín.

.

Is tá mo chroí mar fhuaimnitheoir

do chuisleoirí na cruinne cé

ón uair gur dhein mé fairsing ann

don raidhse tuilteach againn féin.

.

Nuair a leagann damhán géag

go bog ar théada rite a líne

léimeann mo théada féin chun ceoil

á ngléasadh féin dod láimhseáil chruinn.

. . .

“The Harp of Dubhros”

.

Harper, hot your fingers still

stirring me on every string,

look, the night has climbed the hill

yet your noon-day strummings ring.

.

Balmy night bereft of air

slowly take the murmur-strain!

All that is, was ever there,

fugued to fullness and love’s reign.

.

Until the cricket’s drumming rasp,

and insect leg of silver gut,

grey moth-fur emits a gasp,

on music’s web the spider-strut!

.

A sounding box within my chest

for busy buskers everywhere,

for every decibel compressed

recurring in the brightening air.

.

When the spider tests his weave

sweetly on each glistening line:

all my harp-strings leap and heave

– knowing that the tuning’s fine.

.

Translation from Irish © Gabriel Rosenstock

. . .

Michael Davitt (1950 – 2005)

“An Sceimhlitheoir”

.

Tá na coiscéimeanna tar éis filleadh arís.

B’fhada a gcosa gan lúth gan

fuaim.

.

Seo trasna mo bhrollaigh iad

is ní féidir liom

corraí;

.

stadann tamall is amharcann siar

thar a ngualainn is deargann

toitín.

.

Táimid i gcúlsráid dhorcha gan lampa

is cloisim an té ar leis

iad

.

is nuair a dhírím air féachaint cé atá ann

níl éinne

ann

.

ach a choiscéimeanna

ar comhchéim le mo

chroí.

. . .

“The Terrorist”

.

The footsteps have returned again.

The feet for so long still

and silent.

.

Here they go across my breast

and I cannot

resist;

.

they stop for a while, glance

over the shoulder, light

a cigarette.

.

We are in an unlit backstreet

and I can hear who

they belong to

.

and when I focus to make him out

I see there is

no one

.

but his footsteps

keeping step with my

heart.

.

Translation from Irish: Michael Davitt / Philip Casey

. . .

Cathal Ó Searcaigh (born 1956)

“I gCeann Mo Thrí Bliana A Bhí Mé”

(do Anraí Mac Giolla Chomhaill)

.

“Sin clábar! Clábar cáidheach,

a chuilcigh,” a dúirt m’athair go bagrach

agus mé ag slupairt go súgach

i ndíobhóg os cionn an bhóthair.

“Amach leat as do chuid clábair

sula ndéanfar tú a chonáil!”

.

Ach choinnigh mé ag spágáil agus ag splaiseáil

agus ag scairtigh le lúcháir:

“Clábar! Clábar! Seo mo chuid clábair!”

Cé nár chiallaigh an focal faic i mo mheabhair

go dtí gur mhothaigh mé i mo bhuataisí glugar

agus trí gach uile líbín de mo cheirteacha

creathanna fuachta na tuisceana.

.

A chlábar na cinniúna, bháigh tú mo chnámha.

. . .

“When I was three”

(for Anraí Mac Giolla Chomhaill)

.

“That’s muck! Filthy muck, you little scamp,”

my father was so severe in speech

while I was messing happily

in my mud-trench by the road.

“Out with you from that muck

before you freeze to death!”

.

But I continued shuffling, having fun,

all the time screaming with delight:

“Muck! Muck! It’s my own muck!”

But the word was nothing in my innocence

until I felt the squelch of wellies

and, through the dripping of wet clothes,

the shivering knowledge of water.

.

Ah! Muck of destiny, you drenched my bones!

.

Translation from Irish © Thomas Mc Carthy

. . .

Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill (born 1952)

“Ceist na Teangan”

.

Cuirim mo dhóchas ar snámh

i mbáidín teangan

faoi mar a leagfá naíonán

i gcliabhán

a bheadh fite fuaite

de dhuilleoga feileastraim

is bitiúman agus pic

bheith cuimilte lena thóin

.

ansan é a leagadh síos

i measc na ngiolcach

is coigeal na mban sí

le taobh na habhann,