Remembrance Day Reflections: Juliane Okot Bitek

Posted: November 11, 2013 Filed under: 7 GUEST EDITORS, English, Juliane Okot Bitek Comments Off on Remembrance Day Reflections: Juliane Okot BitekZP Guest Editor – Juliane Okot Bitek

Forgetting and Remembrance Day

.

I used to think that Remembrance Day was restricted to soldiers lost in the wars that Canada was involved in. I used to wish that I could remember my brother on Remembrance Day, in a public way, as one of a family who had lost one of its brightest and as one of a community which had lost hundreds and thousands of men and women in the various wars that were fought in my homeland of Uganda. I wanted desperately to claim Remembrance Day for us, because we too had lost a great love and a great life. But I thought it was an imposition, so I wore red poppies like everyone else and reflected on the Canadian dead and listened to speeches about how the veterans had fought for our freedom and how we owe them the comforts of our lives.

I heard my brother call out to me on a sunny morning, just after a high school assembly as me and my friends made our way to class. I looked about. I didn’t see. My brother called out again. It was an urgent call, loud. I turned around, asked one of my friends if she’d heard my name being called. No, she said. She didn’t hear anything. A couple of days later, I was picked up from school and taken home. My brother had been shot.

My brother, Keny, was an officer in the Uganda National Liberation Army, the post-Idi Amin government army. Story was that he was in Fort Portal, a town in western Uganda, and that officers did not usually fight on the frontline. Story was that my brother and other officers were on the frontline, fighting the guerrillas that would eventually make up the current government of Yoweri Museveni. Story was that my brother was shot in that battle, and that he wasn’t the only one. The weekend of Keny’s funeral, there were eight other funerals for eight others killed from the same region – the Acholi region of northern Uganda. It was a sunny day, no evidence of rain for days to come; it was hot. The kind of day that evoked memories of my brother walking with his wife and toddler to his hut during the funeral rites of my father, scant months before. There was a gun salute, I think, with the solemnity befitting an officer. And it wasn’t a grey day, it wasn’t November. The ache from losing my brother would remain just under my skin for years.

I wanted to be a soldier once. When the Canadian military would set up a booth seeking to attract students from the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. I’d pick up a brochure, take the fridge magnet or the pen they offered, the type that came with sticky notes at the other side. I wanted the chance to join the army and make it as high up as my brother might have done.

Remembrance Day in Canada is usually celebrated with wreaths and the marching of proud veterans who are often shuffling along with age and carried along with pride. Black and white film clips from the First and Second World Wars, Korea; video clips from Afghanistan. News channels often focus on the celebration of our soldiers’ efforts at the local cenotaph where a solemn declaration, carved in stone, is ignored for most of the year. Often it’s raining – a grey day, a grey month, a grey time for families who think of November 11th as a national marker for those they loved and lost, and for those who never returned whole.

Sometime after my brother Keny‘s funeral, I returned to school and tried to melt back into normal. The deaths of my brother and father in such quick succession would’ve been hard to ignore but Ugandans have weathered loss for so long and we know how to pick up, keep moving, keep smiling, keep going. Our English teacher gave us a composition exercise in which we were to write a story that ended with lines from the title of Kenyan poet, Jared Angira’s poem, “No Coffin, No Grave”. We had to write a story that was true, from our own experience, no less. What came pouring out of me was the story of losing my brother. I wrote about my sister-in-law who had gone to identify his body, and I could hear her wracked in pain as she narrated her experience. I wrote about how she identified my brother by a bracelet that she had given him. How it was that he had to be buried quickly, how it had to be a closed coffin affair. And how it was that we never had the chance to say goodbye – not really.

Keny had come to visit me in school the term before. He had come in full military regalia. He stood up when he saw me – and saluted. I saluted back – and giggled. He wanted to know how I was, if there was anyone bothering me. And if there was, I was to promise that he’d take care of it. You know how big brothers are – bragging, seemingly full of themselves. He told me not to worry about anything, that I’d be alright. Perhaps Keny had come to say goodbye, and I didn’t know – I did not know that.

There are families for whom Remembrance Day is Every Day or most days. National gratitude doesn’t and cannot match personal grief and it’s hard to argue with a public show of support and the recognition of soldiers. Often we hear phrases about how our soldiers fought for our freedom. That gives me pause: from whom do Canadian soldiers wrest our freedom? How do they do that? What do we do, for example, with the images we’ve seen from Elsipogtog just last month?

When Canada joined the war effort in Afghanistan in 2002, a professor in the English department at the University of British Columbia started to keep count of the losses. Canadians would never let fifty soldiers die over there. But fifty came and went. The faces and names on the professor’s door grew. If it got to a hundred, surely Canadians would be up in arms. A hundred soldiers died, and more; Remembrance Day was commemorated like all the other ones. A hundred and fifty eight Canadian soldiers died in Afghanistan and there was no uproar here, just another solemn Remembrance Day on November 11th.

Soldiers die, their families hurt. Soldiers live with terribly injured bodies, their families hurt. Soldiers get so badly scarred psychically that it should give us pause to think about what it means to maintain an army, to have young people sign up for duty. And then we think about them once a year – with so much solemnity and pomp. But some soldiers go it alone…

Months, years later, I would think about my brother Keny and how useless his advice had been. I worried – and he wasn’t there. I hurt, and people hurt me – and he wasn’t there. He wasn’t there to take care of the nastiness that we had to go through. He wasn’t there when my grade-school teacher returned with our marked composition papers on the “No Coffin, No Grave” theme and insisted that there was one paper that she wanted to read out – and it was mine. She held it up as an example of what not to write. After she’d read it to the class, she turned to me and asked me how it was I could lie like that, to make up such a story. And that I should be ashamed of myself, she admonished me. She told me to leave the classroom and, as I walked out in shame, the tears that threatened to choke me, I willed them to stay back; I was not going to cry.

Keny wasn’t there when I turned thirty three, his age when he died.

I think about the loss of lives of young men and women who sign up for military duty to defend their country, to fight for the rights of others, to invade other nations or to assist in reclaiming Life after disasters like Typhoon Haiyan in The Philippines – which struck land on November 7th and 8th. This is hard and dangerous work, and sometimes it’s awfulwork that returns with evidence of our armed men and women engaging in shameful acts such as the 1993 hazing of Shidane Arone in Somalia. And look at the evidence provided by the recent deconstruction of the Black Blouse Girl photo which shows that there was rape before the Massacre at My Lai. How can we continue to maintain an institution that drives our men and women to such depths, then we commemorate the wars that led them to their deaths? How then can we forget so fast, so completely?

Last summer, I had the privilege of visiting with my nephew, Keny’s son. I was going to be seeing him for the very first time since I left home in 1988. I took the train from Vancouver to Eugene, Oregon, and had dinner with him and his fiancée. My nephew grew up without his father and has no idea whose spectre walks beside him. He feels like Keny, sounds like him. He even called me waya – aunt – butthere was no urgency in his voice, not like the one I’d heard almost three decades ago one morning after assembly. We talked about all kinds of things, but nothing about the gaping absence between us. Time had collapsed to have us meet and know each other, but not enough to have my brother back.

Remembrance Day is packed full of history and valour – Canada has lost many brave women and men to the nastiness that is war. This country, and other countries which have lost brave men and women, can step up to count themselves as courageous and freedom- loving, but when are we going to be inspired by the enormity of loss to seek a future in which there are no more wars and no more losses to war? The list of dead Canadian soldiers no longer hangs on that professor’s door – but we remember what hurts, some of us do.

Addendum: In fact, that list of soldiers‘ names on the door of the professor in the English Department is still there. I have visited his office several times since I graduated in 2009, but I stopped seeing. By his own admittance, the list needs to be updated but still, it says something to me that forgetting is an active process and possibly it begins by stopping seeing what’s in front of us. I’m grateful to Professor Zeitlin for reminding me that peace is a worthwhile pursuit and it begins with the intention to see, to remember and to question what it is we must never forget.

Addendum: In fact, that list of soldiers‘ names on the door of the professor in the English Department is still there. I have visited his office several times since I graduated in 2009, but I stopped seeing. By his own admittance, the list needs to be updated but still, it says something to me that forgetting is an active process and possibly it begins by stopping seeing what’s in front of us. I’m grateful to Professor Zeitlin for reminding me that peace is a worthwhile pursuit and it begins with the intention to see, to remember and to question what it is we must never forget.

. . . . .

Poems for Remembrance Day: El Salvador’s Civil War

Posted: November 11, 2013 Filed under: English, Spanish | Tags: Remembrance Day poems Comments Off on Poems for Remembrance Day: El Salvador’s Civil War Families looking for “Disappeared” relatives in The Book of the Missing at the Human Rights Commission Office in San Salvador_early 1980s_photograph © Eli Reed

Families looking for “Disappeared” relatives in The Book of the Missing at the Human Rights Commission Office in San Salvador_early 1980s_photograph © Eli Reed

.

Carolyn Forché (born 1950, Detroit, Michigan, U.S.A.)

“The Colonel”

.

What you have heard is true. I was in his house. His wife carried

a tray of coffee and sugar. His daughter filed her nails, his son went

out for the night. There were daily papers, pet dogs, a pistol on the

cushion beside him. The moon swung bare on its black cord over

the house. On the television was a cop show. It was in English.

Broken bottles were embedded in the walls around the house to

scoop the kneecaps from a man’s legs or cut his hands to lace. On

the windows there were gratings like those in liquor stores. We had

dinner, rack of lamb, good wine, a gold bell was on the table for

calling the maid. The maid brought green mangoes, salt, a type of

bread. I was asked how I enjoyed the country. There was a brief

commercial in Spanish. His wife took everything away. There was

some talk then of how difficult it had become to govern. The parrot

said hello on the terrace. The colonel told it to shut up, and pushed

himself from the table. My friend said to me with his eyes: say

nothing. The colonel returned with a sack used to bring groceries

home. He spilled many human ears on the table. They were like

dried peach halves. There is no other way to say this. He took one

of them in his hands, shook it in our faces, dropped it into a water

glass. It came alive there. I am tired of fooling around he said. As

for the rights of anyone, tell your people they can go fuck them-

selves. He swept the ears to the floor with his arm and held the last

of his wine in the air. Something for your poetry, no? he said. Some

of the ears on the floor caught this scrap of his voice. Some of the

ears on the floor were pressed to the ground.

May 1978

. . .

Carolyn Forché (nacida en 1950, Detroit, Michigan, EE.UU.)

“El Coronel”

.

Lo que has oído es verdad. Estuve en su casa. Su mujer llevaba

una bandeja con café y azúcar. Su hija se limaba las uñas, su

hijo salió esa noche. Había periódicos, perritos, una pistola

sobre el cojín a su lado. La luna se mecía desnuda con su

cuerda negra encima de la casa. En la televisión daban un

programa policíaco. Era en inglés. Había botellas rotas

empotradas en la cerca que rodeaba la casa para arrancar las

rodilleras de un hombre o cortar sus manos en pedazos. En

las ventanas, rejas como las de las tiendas de licores. Cenamos

cordero a la parrilla, un buen vino; una campanilla de oro estaba

sobre la mesa para llamar a la criada. Ella nos trajo mangos

verdes, sal, un pan especial. Me preguntaron si me gustaba el

país. Hubo un breve anuncio en español. Su mejor se lo llevó

todo. Luego se habló sobre lo difícil que ahora resultaba

gobernar. El loro dijo “hola” en la terraza. El coronel le dijo

que se callara, y se levantó pesadamente de la mesa. Mi amigo

me dijo con sus ojos: no digas nada. El coronel volvió con

una bolsa de las que se usan para traer comestibles a casa.

Esparció muchas orejas humanas sobre la mesa. Eran como

orejones dulces partidos en dos. No hay otra manera de decirlo.

Cogió una en sus manos, la sacudió en nuestra presencia, y la

dejó caer en un vaso de agua. Allí revivió. Estoy hasta las

narices de tonterías, dijo. En cuanto a los derechos humanos,

dile a tu gente que se joda. Con su brazo tiró todas las orejas

al suelo y levantó en el aire el resto de su vino. Algo para tu

poesía, ¿no?, me dijo. Algunas orejas del suelo recogieron este

retazo de su voz. Algunas orejas del suelo fueron aplastadas

contra la tierra.

Mayo de 1978

.

Traducción del inglés: Noël Valis

. . .

Jaime Suárez Quemain (Salvadorean poet and journalist, 1949-1980)

“A Collective Shot”

.

In my country, sir,

men carry a padlock

on their mouths,

only when alone do they meditate,

shout and protest

because fear, sir,

is the gag

and the subtle padlock you control.

In my country, sir,

(I say mine because I want it to be mine)

even on the fence posts

you can see the longing

…they divide it, they rent it, they mortgage it,

they torture it, they kill it, they imprison it,

the newspapers declare there is total freedom, but

it’s only in the saying, sir, you know what I mean.

And it’s my country,

with its streets, its shadows, its volcanos,

its high-rises – dens of thieves –

whose children succeeded in escaping Malthus,

it’s my country, with its poets, its dreams and its roses.

And my country, sir,

is nearly a cadaver, a solitary phantom of the night,

and it agonizes,

and you, sire,

so impassive.

.

Translation from Spanish: Wilfredo Castaño

.

National Policemen using an ice-cream vendor as a shield during a skirmish with demonstrators_San Salvador_early 1980s_photograph © Etienne Montes

National Policemen using an ice-cream vendor as a shield during a skirmish with demonstrators_San Salvador_early 1980s_photograph © Etienne Montes

Arrest of an autorepair mechanic for failure to carry an ID card_San Salvador_early 1980s_photograph copyright John Hoagland

Arrest of an autorepair mechanic for failure to carry an ID card_San Salvador_early 1980s_photograph copyright John Hoagland

.

Jaime Suárez Quemain (poeta y periodista salvadoreño, 1949-1980)

“Un Disparo Colectivo”

.

En mi país, señor,

los hombres llevan un candado

en la boca,

sólo a solas

meditan, vociferan y protestan,

porque el miedo, señor,

es la mordaza

y el candado sutil que usted maneja.

En mi país, señor,

– digo mío porque lo quiero mío –

hasta en los postes

se mira la nostalgia,

lo parcelan, lo alquilan, lo hipotecan,

lo torturan, lo matan, lo encarcelan;

la prensa dice

que hay libertad completa,

es un decir, señor, usted lo sabe.

Y es así mi país,

con sus calles, sus sombras, sus volcanes,

sus grandes edificios – albergues de tahures –

sus niños que lograron

escapársele a Malthus,

sus poetas, sus sueños y sus rosas.

Y mi país, señor,

casi cadáver,

solitario fantasma de la noche,

agoniza… y usted:

tan impasible.

. . .

Alfonso Quijada Urías (Salvadorean poet, born 1940)

“Chronicle”

.

The dead man’s mother is buying flowers,

the village is lovely, yellow flowers bloom on the hills;

the day seems happy, though it’s really very sad,

nothing moves without God’s will.

And the police are buying flowers, which they’ll send

to the dead man’s mother,

and a humble righteous man sends a note of condolence

for the death of the man they killed.

The sun keeps shining on the hills,

then a man playing the saddest music feels sorry to be there

among those men much deader than the dead man himself

who is swallowing with his open eyes the flowering hills,

the village and the walls, where once he wrote: long lib liberti.

.

(1983)

.

Translation from Spanish: Barbara Paschke

. . .

Alfonso Quijada Urías (poeta salvadoreño, nacido 1940)

“Crónica”

.

La madre del muerto compra flores,

el pueble es bello, en los cerros crecen las flores amarillas;

parece un día alegre aunque realmente es muy triste,

nada se mueve sin la voluntad de Dios.

También los policías compran flores que mandaran a

la madre del muerto,

también un hombre bajito de conciencia manda

una nota en la que se conduele

por la muerte del muerto que mataron.

El sol sigue brillando sobre los cerros.

Entonces un hombre que toca la música mas triste

se conduele de estar allí

entre esos hombres mucho más muertos que el mismo muerto

que va tragando con sus ojos abiertos los cerros florecidos,

el pueblo y sus paredes, donde escribió una tarde: biva la libertá.

.

(1983)

A Salvadorean government soldier with his automatic rifle and a sleeping toddler, after an anti-guerrilla manoeuvre in Cabañas province, El Salvador_May 1984

A Salvadorean government soldier with his automatic rifle and a sleeping toddler, after an anti-guerrilla manoeuvre in Cabañas province, El Salvador_May 1984

.

El Salvador, at the advent of the 20th century, was governed by presidents drawn from its oligarchical families; these had a cozy yet volatile relationship with the nation’s military. In the last decades of the 19th century, mass production at fincas (plantations) of coffee beans for export as the main cash crop was already being emphasized through forced elimination of communal land ownings belonging to campesinos (peasant farmers). In fact, a rural police force was created in 1912 to keep displaced campesinos in line. Social activist Farabundo Martí (1893-1932), one of the founders of the Communist Party of Central America, spearheaded a peasant uprising in 1932 which resulted in 30,000 deaths by the military – La Matanza (“The Slaughter”), as it came to be known. Decades of repression followed, then a coup d’état in1979 plus the 1980 assassination of human-rights advocate, Salvadorean Archbishop Oscar Romero, triggered a brutal civil war that lasted more than a decade. In the U.S.A., the newly elected President, Ronald Reagan, was determined to limit what he perceived as Communist and/or Leftist influence in Central America following the popular insurrection that overthrew the Somoza dictatorship in neighbouring Nicaragua, so the U.S. administration supported the Salvadorean junta with military and economic aid throughout the 1980s. During this time, death squads associated with the military terrorized civilians, sometimes massacring hundreds of people at a time, as at El Mozote * in December of 1981. All told, the war cost the lives of 75,000 civilian noncombatants – this, in a country of a mere 5.5 million people (1992 estimate.).

In the U.S.A. the general population was divided about Washington’s deepening engagement in El Salvador. University student committees and humanitarian church groups coalesced around the issue. While there were major demonstrations in U.S. cities protesting its government’s policies in the tiny Central American country – 1981 saw rallies in several U.S.cities, and one that grouped in front of the Pentagon in May that year had 20,000 participants calling for Solidarity with the People of El Salvador – the continued violence against el pueblo salvadoreño and the U.S. foreign policies that enabled it – made the unfolding “story” of the Salvadorean civil war of the 1980s one of the central parables of the Cold War era. Then, unexpectedly, in 1989, it was a crime truly capturing international attention – the murder by Salvadorean government forces of six Jesuit priests, along with their housekeeper and her daughter – that began to set in motion the wheels of peace. A United Nations Truth Commission investigated and this gradually led to a UN-brokered peace agreement, signed at Chapultepec Castle in México City in 1992. Today, there are free elections in El Salvador, and both sides of the conflict have been integrated into the political process. Yet the economy remains unstable—about 20 percent-dependent upon remittances sent home by Salvadoreans working in the U.S.A. and other countries.

.

* El Mozote, a hamlet in the mountainous Morazán region of El Salvador, was the scene of an orgy of killing by the Salvadorean Army’s Atlacatl Battalion (trained by the U.S.military) which had arrived in the vicinity searching for guerrillas of the FMLM (Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front). Campesinos had gathered in El Mozote seeking a safe haven. The Atlacatl forced everyone into the village square, where they separated the men from the women. The men were interrogated, tortured, then executed. The women and girls were rapedthen machine-gunned down. Children had their throats slit then their bodies were hung from trees. Every building – and numerous piles of bodies – were set ablaze. The entire civilian population of El Mozote and its peripheral farms was eliminated. Author Mark Hertsgaard, in his book On Bended Knee – a study of the media and the Reagan administration – wrote of the significance of the first New York Times and Washington Post reports (January 1982) of the massacre: “What made the El Mozote/Morazán massacre stories so threatening was that they repudiated the fundamental moral claim that undergirded U.S. policy. They suggested that what the United States was supporting in Central America was not democracy but repression. They therefore threatened to shift the political debate from means to ends, from how best to combat the supposed Communist threat—send US troops or merely US aid?—to why the U.S.A. was backing state terrorism in the first place.”

. . . . .

Poems for Remembrance Day: Siegfried Sassoon / El soldado sincero – y amargo: la poesía de Siegfried Sassoon

Posted: November 11, 2013 Filed under: English, Siegfried Sassoon, Spanish | Tags: Remembrance Day poems Comments Off on Poems for Remembrance Day: Siegfried Sassoon / El soldado sincero – y amargo: la poesía de Siegfried Sassoon.

Siegfried Sassoon (United Kingdom, 1886-1967) is best remembered for his angry and compassionate poems of the First World War (1914-1918). The sentimentality and jingoism of many War poets is entirely absent in Sassoon‘s poetic voice. His is a voice of intense feeling combined with cynicism. He wrote of the horror and brutality of trench warfare and contemptuously satirized generals, politicians, and churchmen for their incompetence and blind support of the War.

.

Siegfried Sassoon’s Declaration against The War (July 1917)

“I am making this statement as an act of wilful defiance of military authority, because I believe that the War is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it. I am a soldier, convinced that I am acting on behalf of soldiers. I believe that this War, on which I entered as a war of defence and liberation, has now become a war of aggression and conquest. I believe that the purpose for which I and my fellow soldiers entered upon this war should have been so clearly stated as to have made it impossible to change them, and that, had this been done, the objects which actuated us would now be attainable by negotiation. I have seen and endured the sufferings of the troops, and I can no longer be a party to prolong these sufferings for ends which I believe to be evil and unjust. I am not protesting against the conduct of the war, but against the political errors and insincerities for which the fighting men are being sacrificed. On behalf of those who are suffering now I make this protest against the deception which is being practised on them; also I believe that I may help to destroy the callous complacency with which the majority of those at home regard the contrivance of agonies which they do not, and which they have not, sufficient imagination to realize.”

. . .

Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967)

“Suicide in the trenches”

.

I knew a simple soldier boy

Who grinned at life in empty joy,

Slept soundly through the lonesome dark,

And whistled early with the lark.

.

In winter trenches, cowed and glum,

With crumps and lice and lack of rum,

He put a bullet through his brain.

No one spoke of him again.

.

You smug-faced crowds with kindling eye

Who cheer when soldier lads march by,

Sneak home and pray you’ll never know

The hell where youth and laughter go.

. . .

“Suicidio en las trincheras”

.

Conocí a un soldado raso

que sonreía a la vida con alegría hueca,

dormía profundamente en la oscuridad solitaria

y silbaba temprano con la alondra.

En trincheras invernales, intimidado y triste,

con bombas y piojos y ron ausente,

se metió una bala en la sien.

Nadie volvió a hablar de él.

Vosotros, masas ceñudas de ojos incendiados

que vitoreáis cuando desfilan los soldados,

id a casa y rezad para no saber jamás

el infIerno al que la juventud y la risa van.

. . .

“Attack”

.

At dawn the ridge emerges massed and dun

In the wild purple of the glow’ring sun,

Smouldering through spouts of drifting smoke that shroud

The menacing scarred slope; and, one by one,

Tanks creep and topple forward to the wire.

The barrage roars and lifts. Then, clumsily bowed

With bombs and guns and shovels and battle-gear,

Men jostle and climb to, meet the bristling fire.

Lines of grey, muttering faces, masked with fear,

They leave their trenches, going over the top,

While time ticks blank and busy on their wrists,

And hope, with furtive eyes and grappling fists,

Flounders in mud. O Jesus, make it stop!

. . .

“Ataque”

.

Surge al alba enorme y parda la colina

en el salvaje sol púrpura de frente fruncida

ardiendo a través de columnas de humo a la deriva

envolviendo

la amenazadora pendiente arrasada; y, uno a uno,

los tanques se arrastran y vuelcan la alambrada.

La descarga ruge y se eleva. Después, torpemente agachados

con bombas y fusiles y palas y uniforme completo,

los hombres empujan y escalan para unirse al encrespado

fuego.

Filas de rostros grises, murmurantes, máscaras de miedo,

abandonan sus trincheras, pasando por la cima,

mientras el tiempo pasa en blanco apresurado en sus

muñecas

y aguardan, con ojos furtivos y puños cerrados,

luchando por flotar en el barro. ¡Oh Dios, haz que pare!

. . .

“The Investiture”

.

God with a Roll of Honour in His hand

Sits welcoming the heroes who have died,

While sorrowless angels ranked on either side

Stand easy in Elysium’s meadow-land.

Then you come shyly through the garden gate,

Wearing a blood-soaked bandage on your head;

And God says something kind because you’re dead,

And homesick, discontented with your fate.

.

If I were there we’d snowball Death with skulls;

Or ride away to hunt in Devil’s Wood

With ghosts of puppies that we walked of old.

But you’re alone; and solitude annuls

Our earthly jokes; and strangely wise and good

You roam forlorn along the streets of gold.

. . .

“La investidura”

.

Con una lista de caídos en Su mano, Dios

se sienta dando la bienvenida a los héroes que han muerto

mientras ángeles sin pena se alinean a cada lado

tranquilos en pie en los prados Elíseos.

Entonces, tú llegas tímido al jardín a través de las puertas

luciendo un vendaje empapado en sangre en la cabeza

y Dios dice algo amable porque estás muerto

y añoras tu casa, descontento con tu destino.

Si yo estuviera allí, lanzaríamos calaveras como bolas de

nieve a la muerte

o nos fugaríamos para cazar en el Bosque del Diablo

con fantasmas de cachorros que antaño paseamos.

Pero estás solo y la soledad anula

nuestras bromas terrenas; y extrañamente sabio y bueno

vagas desamparado por calles de oro.

. . .

From: Counter-Attack and Other Poems (1918)

Spanish translations © Eva Gallud Jurado (Salamanca, 2011)

De: Contraataque y otros poemas(1918)

Traducciones de Eva Gallud Jurado – derechos de autor (Salamanca, 2011)

. . . . .

Andre Bagoo / Tomorrow Please God: poems from the premiere issue of Douen Islands

Posted: November 5, 2013 Filed under: Andre Bagoo, English Comments Off on Andre Bagoo / Tomorrow Please God: poems from the premiere issue of Douen IslandsShip of Theseus

.

I have to see your face

if am not going to stare.

.

How do we know for sure

a dead body is really there?

.

Call all you wed by my surname

so that when I die, we breathe

.

in your body, in your new lover

and then, later, his new lover

.

his and his. In this way

our marriage lasts forever.

Father of the Nation

.

My life should grow longer

With each moment you live

We, strange twins, each

Approaching middle-age

Through reversed ends

.

Assuming I will live tomorrow

I can time my midlife crisis

My life chained to yours

Our wrong-footed estimates

Leave one set of footprints

. . .

Dragon Boat

.

I will put my bucket down

Over my head

And turn it into straw, spin

Bark into gold.

Our ways always hold.

We cup love with tightness.

We know enough of currency

To know.

When you see me

You always say,

“Excuse me, you from China?”

You’ve nearly understood.

Our ways are old

Our bodies, our own.

We don’t take back

What we never gave.

. . .

These poems are taken from Douen Islands, a poetry e-book produced in collaboration by poet Andre Bagoo, graphic designer Kriston Chen, artists Brianna McCarthy and Rodell Warner, and sitarist Sharda Patasar.

Read more here: douenislands.tumblr.com

And get involved here: douenislands@gmail.com

. . . . .

Poem for Beginning Anew: “Zamzam” by Doyali Farah Islam

Posted: November 4, 2013 Filed under: Doyali Farah Islam, English | Tags: Muharram, New Year Comments Off on Poem for Beginning Anew: “Zamzam” by Doyali Farah IslamDoyali Farah Islam

“Zamzam”

.

Zamzam was found

under a heap of dung,

where the blood of rites

fertilized stone.

.

… Zamzam … was found …

under a heap of dung.

.

it was ‘Abd al-Muttalib

who decided which to cherish.

.

it wasn’t just springwater,

but his decision

that was the freshness.

.

… this ground we unmuck

called listening heart

carves deep the shallowest

cup.

.

somewhere breathes its breath

from between your two breasts.

.

(no need to divine

perfect locations;

approximations are enough.)

.

… out in the plain open, I was searching for a particular thing,

and a thousand hidden

wellsprings of treasure

passed me by.

.

Hajar runs between two hills, desperate to find what quenches thirst.

.

then she gives up going back and forth in the desert of fear,

and Ishmael’s heel strikes water.

. . .

Poet’s notes on “Zamzam”:

Zamzam:

The Well of Zamzam was in use from the time of Ishmael and Hajar’s story (explained below), until it was filled with the treasures of pilgrimage offerings by the Jurhumites who controlled Mecca (Lings 4). The Jurhumites covered the well with sand, and the water source was largely forgotten (Lings 5). Many years later, ‘Abd al-Muttalib, sleeping near the Ka‘bah, heard the Divine command, “Dig Zamzam!” (Lings 10). The well was recovered, and it still serves Muslim pilgrims on Hajj.

‘Abd al-Muttalib:

While the “heap” element in the poem is hyperbolic, Muhammad’s grandfather, ‘Abd al-Muttalib, did re-locate the spring of Zamzam near the Ka‘bah at the site upon which he found dung, an ant’s nest, as well as blood from ritual sacrifices performed by the Quraysh (Lings 10-11).

Hajar and Ishmael:

Hajar (Biblical: Hagar), the second wife of Abraham, after Sarah, was alone in the desert with her baby, Ishmael. Desperate to find water, she ran between two hillocks – now called Safā and Marwah – so that she could view the desert from better vantage points. After seven tries with no sight of a caravan, she gave up and sat down. A well sprang up where Ishmael’s heel touched the ground (Lings 2-3). This well became the Well of Zamzam.

.

Reference: Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources by Martin Lings (Inner Traditions/Bear & Co.) © 1983, 1991, 2006, originally published in the UK by George Allen & Unwin © 1983.

. . .

“Zamzam” is taken from Doyali Farah Islam’s 2011 collection, Yūsuf and the Lotus Flower, published by Buschek Books in Ottawa, Canada.

Doyali Farah Islam is the first-place winner of Contemporary Verse 2’s 35th Anniversary Contest, and her poems have appeared in Grain Magazine (38.2), amongst other places. Born to Bangladeshi parents, Islam grew up in Toronto and spent four years abroad in London, England. As to her true dwelling place, she can only offer: “I am borrowed breath. / if you too are borrowed, / we meet in the home of our breather.” Islam holds a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature and Equity Studies from the University of Toronto (Victoria College).

.

Image: Water – a photograph by Laboni Islam

. . . . .

All Souls Day and Dorothy Parker: “You might as well live.”

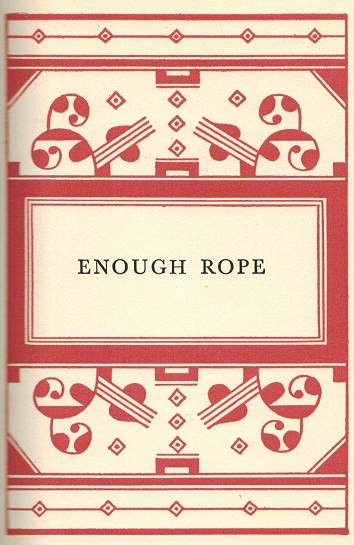

Posted: November 2, 2013 Filed under: Dorothy Parker, English Comments Off on All Souls Day and Dorothy Parker: “You might as well live.” ZP_Frontispiece for Dorothy Parker’s Enough Rope_1926_taken from her 1936 collected poems entitled Not so deep as a well

ZP_Frontispiece for Dorothy Parker’s Enough Rope_1926_taken from her 1936 collected poems entitled Not so deep as a well

.

In 1914, 21-year-old Dorothy Parker was hired by Vogue magazine in New York as an editorial assistant. By 1918 she was a staff writer for Vanity Fair where she began penning play reviews in place of an on-holiday P.G. Wodehouse.

The way she wrote – how to describe it? This was something new: cute as a button, sharp as a tack; the driest gin with a drop of grenadine syrup. After two years the editor fired her for offending a bigwig producer (Broadway impresario Flo Ziegfeld), but she had already made a name for herself as a “fast woman” – fast with words, that is. Throughout the 1920s she would contribute several hundred poems and numerous columns to Life, McCall’s, Vogue, The New Republic, and The New Yorker (where she was one of that magazine’s earliest contributors when it began publishing in 1925.) Whatever her snappy, clever, seemingly off-the-cuff social commentaries projected – whether in theatre / book reviews or luncheon quips as a “member” of The Algonquin Round Table – Dorothy Parker’s poetry dealt much in love’s loss or love’s rejection; melancholy and sorrow; the appealing thought of one’s own Death.

ZP_a young Dorothy Parker_around 1918

ZP_a young Dorothy Parker_around 1918

Parker is a poet who’s just right to feature on All Souls Day. Indeed, she made the magnetic appeal of Death plain in her book titles: Death and Taxes, Laments for the Living, and Here Lies. We celebrate her peculiarly morbid liveliness with words, a liveliness she displayed even when she was really really down and joked – seriously – as only she could – about suicide. Quoted in Vanity Fair in 1925, Parker proposed that her epitaph be: “Excuse my dust.” Mistress of self-deprecation or being on the attack; vulnerable and wistful or hard as nails; Parker was such things. This made her – still makes her today – a complex ‘read’. But she’s worth it.

.

Born in 1893 to a German-Jewish father and a mother of Scottish descent who died when Dorothy was four years old, Parker (her married name from her first husband, a Wall-Street stockbroker, in 1917) – referred to her stepmother, whom her father married in 1900, as “the housekeeper” – early evidence of that wise-crack wit. Her father died in 1913, and by then Parker was already earning a living playing piano at a dance studio…and beginning to work on her verse.

.

Parker in the next two decades wrote a handful of incisive, bittersweet short stories – “Big Blonde” won the 1929 O. Henry Award – and her literary reputation rests on those pieces as much as on her poetry. In 1928 she divorced from her first husband then had a series of affairs, one of which resulted in an abortion and a suicide attempt (among several over the years). Of that amour and pregnancy she remarked: “How like me to put all my eggs into one bastard.”

.

But even by the time she reached middle age she remained insecure about her literary abilities. And upon her death in 1967 – of a heart attack, not suicide – she was living in an apartment-hotel in Manhattan and was – in truth – “forgotten but not gone.” In a 1956 interview in The Paris Review she stated: “There’s a hell of a distance between wise-cracking and wit. Wit has truth in it; wise-cracking is simply calisthenics with words.” For this was one of her gnawing worries: was she just a wise-cracker and not a true wit? In fact, she was both – and in the New York of the 1920s – at least until the Wall Street “crash” of 1929 – there was room for the two; the wise-cracker got more press, though. One of her best poems combines both wise-crack and wit, in the right balance – perhaps something only she could do.

“Résumé”

.

Razors pain you;

Rivers are damp;

Acids stain you;

And drugs cause cramp.

Guns aren’t lawful;

Nooses give;

Gas smells awful;

You might as well live.

. . .

“Résumé” is from Parker’s first volume of poetry entitled Enough Rope (published 1926). The following poems are also taken from that collection:

.

“The Small Hours”

.

No more my little song comes back;

And now of nights I lay

My head on down, to watch the black

And wait the unfailing grey.

.

Oh, sad are winter nights, and slow;

And sad’s a song that’s dumb;

And sad it is to lie and know

Another dawn will come.

. . .

“The Trifler”

.

Death’s the lover that I’d be taking;

Wild and fickle and fierce is he.

Small’s his care if my heart be breaking –

Gay young Death would have none of me.

.

Hear them clack of my haste to greet him!

No one other my mouth had kissed.

I had dressed me in silk to meet him –

False young Death would not hold the tryst.

.

Slow’s the blood that was quick and stormy,

Smooth and cold is the bridal bed;

I must wait till he whistles for me –

Proud young Death would not turn his head.

.

I must wait till my breast is wilted,

I must wait till my back is bowed,

I must rock in the corner, jilted –

Death went galloping down the road.

.

Gone’s my heart with a trifling rover.

Fine he was in the game he played –

Kissed, and promised, and threw me over,

And rode away with a prettier maid.

. . .

“A very short Song”

.

Once, when I was young and true,

Someone left me sad –

Broke my brittle heart in two;

And that is very bad.

.

Love is for unlucky folk,

Love is but a curse.

Once there was a heart I broke;

And that, I think, is worse.

. . .

“Light of Love”

.

Joy stayed with me a night –

Young and free and fair –

And in the morning light

He left me there.

.

Then Sorrow came to stay,

And lay upon my breast;

He walked with me in the day,

And knew me best.

.

I’ll never be a bride,

Nor yet celibate,

So I’m living now with Pride –

A cold bedmate.

.

He must not hear nor see,

Nor could he forgive

That Sorrow still visits me

Each day I live.

. . .

“Somebody’s Song”

.

This is what I vow:

He shall have my heart to keep;

Sweetly will we stir and sleep,

All the years, as now.

Swift the measured sands may run;

Love like this is never done;

He and I are wedded one:

This is what I vow.

.

This is what I pray:

Keep him by me tenderly;

Keep him sweet in pride of me,

Ever and a day;

Keep me from the old distress;

Let me, for our happiness,

Be the one to love the less:

This is what I pray.

.

This is what I know:

Lovers’ oaths are thin as rain;

Love’s a harbinger of pain –

Would it were not so!

Ever is my heart a-thirst,

Ever is my love accurst;

He is neither last nor first:

This is what I know.

. . .

“The New Love”

.

If it shine or if it rain,

Little will I care or know.

Days, like drops upon a pane,

Slip and join and go.

.

At my door’s another lad;

Here’s his flower in my hair.

If he see me pale and sad,

Will he see me fair?

.

I sit looking at the floor.

Little will I think or say

If he seek another door;

Even if he stay.

. . .

“I shall come back”

.

I shall come back without fanfaronade

Of wailing wind and graveyard panoply;

But, trembling, slip from cool Eternity –

A mild and most bewildered little shade.

I shall not make sepulchral midnight raid,

But softly come where I had longed to be

In April twilight’s unsung melody,

And I, not you, shall be the one afraid.

.

Strange, that from lovely dreamings of the dead

I shall come back to you, who hurt me most.

You may not feel my hand upon your head,

I’ll be so new and inexpert a ghost.

Perhaps you will not know that I am near –

And that will break my ghostly heart, my dear.

. . .

“Chant for Dark Hours”

.

Some men, some men

Cannot pass a

Book shop.

(Lady, make your mind up, and wait your life away.)

.

Some men, some men

Cannot pass a

Crap game.

(He said he’d come at moonrise, and here’s another day!)

.

Some men, some men

Cannot pass a

Woman.

(Wait about, and hang about, and that’s the way it goes.)

.

Some men, some men

Cannot pass a

Golf course.

(Read a book, and sew a seam, and slumber if you can.)

.

Some men, some men

Cannot pass a

Haberdasher’s.

(All your life you wait around for some damn man!)

. . .

“Unfortunate Coincidence”

.

By the time you swear you’re his,

Shivering and sighing,

And he vows his passion is

Infinite, undying –

Lady, make note of this:

One of you is lying.

. . .

“Inventory”

.

Four be the things I am wiser to know:

Idleness, sorrow, a friend, and a foe.

.

Four be the things I’d been better without:

Love, curiosity, freckles, and doubt.

.

Three be the things I shall never attain:

Envy, content, and sufficient champagne.

.

Three be the things I shall have till I die:

Laughter and hope and a sock in the eye.

. . .

“Philosophy”

.

If I should labour through daylight and dark,

Consecrate, valorous, serious, true,

Then on the world I may blazon my mark;

And what if I don’t, and what if I do?

. . .

“Men”

.

They hail you as their morning star

Because you are the way you are.

If you return the sentiment,

They’ll try to make you different;

And once they have you, safe and sound,

They want to change you all around.

Your moods and ways they put a curse on;

They’d make of you another person.

They cannot let you go your gait;

They influence and educate.

They’d alter all that they admired.

They make me sick, they make me tired.

. . .

“General Review of the Sex Situation”

.

Woman wants monogamy;

Man delights in novelty.

Love is woman’s moon and sun;

Man has other forms of fun.

Woman lives but in her lord;

Count to ten, and man is bored.

With this the gist and sum of it,

What earthly good can come of it?

. . .

The following poems are taken from Parker’s volume Death and Taxes (published 1931):

.

“Requiescat”

.

Tonight my love is sleeping cold

Where none may see and none shall pass.

The daisies quicken in the mold,

And richer fares the meadow grass.

.

The warding cypress pleads the skies,

The mound goes level in the rain.

My love all cold and silent lies –

Pray God it will not rise again!

. . .

“The Lady’s Reward”

.

Lady, lady, never start

Conversation toward your heart;

Keep your pretty words serene;

Never murmur what you mean.

Show yourself, by word and look,

Swift and shallow as a brook.

Be as cool and quick to go

As a drop of April snow;

Be as delicate and gay

As a cherry flower in May.

Lady, lady, never speak

Of the tears that burn your cheek –

She will never win him, whose

Words had shown she feared to lose.

Be you wise and never sad,

You will get your lovely lad.

Never serious be, nor true,

And your wish will come to you –

And if that makes you happy, kid,

You’ll be the first it ever did.

. . .

“Coda” (from Parker’s 1928 volume Sunset Gun)

.

There’s little in taking or giving,

There’s little in water or wine;

This living, this living, this living

Was never a project of mine.

Oh, hard is the struggle, and sparse is

The gain of the one at the top,

For art is a form of catharsis,

And love is a permanent flop,

And work is the province of cattle,

And rest’s for a clam in a shell,

So I’m thinking of throwing the battle –

Would you kindly direct me to Hell?

. . . . .

All Souls Day: “November Rose”, “Autumn Breeze” and “On My Child – Who Died Early” / Allerseelen gedichte: Stefan George, Friedrich Rückert, Rosa Maria Assing

Posted: November 2, 2013 Filed under: English, German | Tags: All Souls Day poems Comments Off on All Souls Day: “November Rose”, “Autumn Breeze” and “On My Child – Who Died Early” / Allerseelen gedichte: Stefan George, Friedrich Rückert, Rosa Maria AssingStefan George (1868-1933)

“November Rose”

.

Tell me, wan rose there,

Why do you continue in such a dreary place?

The autumn is already sinking on the lever of time

November clouds are already drawing towards the mountains

Why do you continue alone, pale rose?

The last of your companions and sisters

Fell dead and petalless to the ground yesterday

And lies interred in its mother’s womb…

Ah, don’t admonish me for hurrying!

I’ll wait a short while yet.

I stand on the grave of a youth:

He of many hopes and charms

How did he die? Why? God only knows!

Before I fade, before I wane

I yet want to adorn

His fresh grave

On the day of death.

. . .

Stefan George

“Novemberrose”

.

Sag mir blasse Rose dort

Was stehst du noch an so trübem ort?

Schon senkt sich der herbst am zeitenhebel

Schon zieht an den bergen novembernebel.

Was bleibst du allein noch blasse rose?

Die letzte deiner gefährten und schwestern

Fiel tot und zerblättert zur erde gestern

Und liegt begraben im mutterschoosse…

Ach mahne mich nicht dass ich mich beeile!

Ich warte noch eine kleine weile.

Auf eines jünglings grab ich stehe:

Er vieler hoffnung und entzücken

Wie starb er? Warum? Gott es wissen mag!

Eh ich verwelke eh ich vergehe

Will ich sein frisches grab

noch schmücken

Am totentag.

. . .

Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866)

“Autumn Breeze”

.

Heart, already so old and yet not wise,

Do you hope from day to day,

That what the blossoming Spring didn’t bring you

Will yet come to you in Fall!

.

The sportive wind doesn’t leave the bush alone,

Always flattering, always caressing.

Its breath unfurls the roses in the morning

And strews the roses in the evening.

.

The sportive wind doesn’t leave the bush alone

Until it strips it bare.

Everything, Heart, that we loved and lyricized

Is a wind and a breath.

. . .

Friedrich Rückert

“Herbsthauch”

.

Herz, nun so alt und noch immer nicht klug,

Hoffst du von Tagen zu Tagen,

Was dir der blühende Frühling nicht trug,

Werde der Herbst dir noch tragen!

.

Läßt doch der spielende Wind nicht vom Strauch,

Immer zu schmeicheln, zu kosen.

Rosen entfaltet am Morgen sein Hauch,

Abends verstreut er die Rosen.

.

Läßt doch der spielende Wind nicht vom Strauch,

Bis er ihn völlig gelichtet.

Alles, o Herz, ist ein Wind und ein Hauch,

Was wir geliebt und gedichtet.

. . .

Rosa Maria Assing (1783-1840)

“On My Child – Who Died Early”

.

We watched, entranced, as a pure little flame

Rose up between us out of the fire of our love

In the life of our sweet beloved child;

And for us the most joyful celebration began!

.

The flame daily lit our way towards new

And sweeter pleasures, and with joyous trembling

We united in the dearest pursuit of the heart,

To care for what was most precious to us.

.

Then death came treading with heavy steps;

The flame that lit our lives so brilliantly

Was extinguished into our deepest trembling.

.

Then life seemed cold and dark to us,

Our faces and eyes were wet with tears;

We shuddered, deeply sunken in grief.

. . .

Already spring breezes are blowing gently again,

And the sweet fragrance of the violets is wafting,

The wind plays with fresh grass and foliage,

And I hear the nightingale lifting her song.

.

So many other things are being and growing,

Everything pushes towards light and life;

But, ah, my tender child can only wilt,

It shall never see another springtime.

.

Not spring breezes, not violets, nightingales,

Nor whatever other pleasures the spring brings,

None of these shall come into your life,

.

For you were devoured so soon by the dark grave!

And for me, as I languish in sorrow over you,

Nothing blooms in spring but my deep woe!

.

(1818)

. . .

Rosa Maria Assing

“Auf mein früh gestorbenes Kind”

.

Wir sahn entzückt aus unsrer Liebe Feuer

Sich zwischen uns ein Flämmchen rein erheben

In des geliebten süßen Kindes Leben;

Und uns begann des höchsten Glückes Feier!

.

Die Flamme glänzte uns zu täglich neuer

Und süßrer Freude, und mit frohem Beben

Vereinten wir des Herzens liebstes Streben,

Zu pflegen was uns über alles theuer.

.

Da kam mit schwerem Tritt der Tod gegangen;

Die Flamme, die so herrlich uns geleuchtet,

Die löschte er zu unserm tiefsten Beben.

.

Nun scheinet kalt und dunkel uns das Leben,

Mit Thränen ist Gesicht und Aug’ befeuchtet;

Wir stehn erschüttert, tief vom Schmerz befangen.

. . .

Schon wehen wieder Frühlingslüfte lind,

Und Veilchen lassen süßen Duft entschweben,

Mit jungem Gras und Laube spielt der Wind,

Auch hör’ ich Nachtigall ihr Lied erheben.

.

So viel auch Wesen und Gewüchse sind,

Es dränget alles sich zum Licht und Leben;

Nur welken mußte, ach, mein zartes Kind,

Es sollte keinen Frühling je erleben!

.

Nicht Frühlingsluft, nicht Veilchen, Nachtigallen,

Und was noch sonst der Frühling Süßes bringt,

Nichts davon sollte in dein leben fallen,

.

Da dich so früh das dunkle Grab verschlingt!

Und mir, die ich in Schmerz um dich vergehe,

Blüht nichts im Frühling als mein tiefes Wehe!

.

(1818)

. . .

Translations from the German © Aaron Swan

. . .

Images:

Rosa Maria Assing_Landschaft mit Quellgöttinnen_a silhouette scene_paper cutout_made by the poet in 1830

Rosa Maria Assing_Märchenlandschan mit Altan_a silhouette scene_paper cutout_made by the poet in 1830

. . . . .

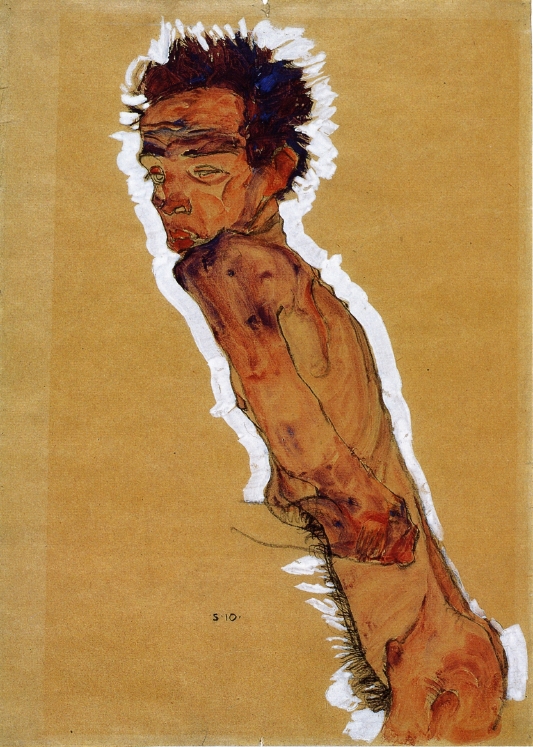

Egon Schiele: Ich bin Mensch, ich liebe / Den Tod und Liebe / Das Leben. “I am a Human Being – I love Death and Love – They are alive.”

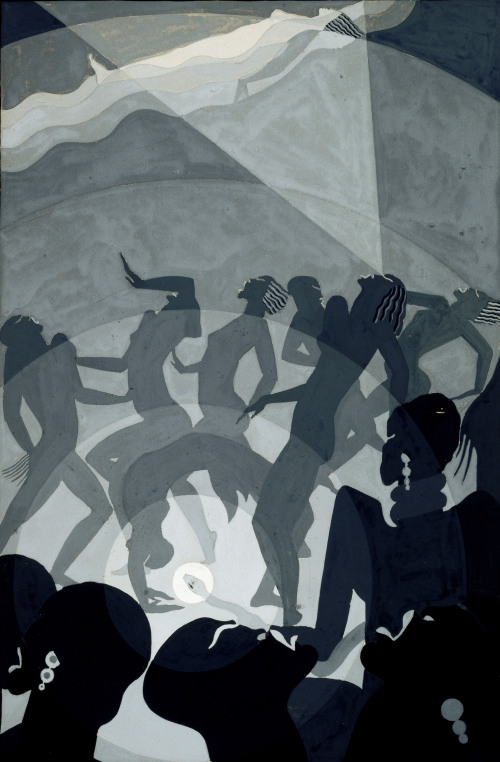

Posted: October 31, 2013 Filed under: A FEW FAVOURITES / UNA MUESTRA DE FAVORITOS, Egon Schiele, English, German | Tags: German Expressionist poets Comments Off on Egon Schiele: Ich bin Mensch, ich liebe / Den Tod und Liebe / Das Leben. “I am a Human Being – I love Death and Love – They are alive.” ZP_Egon Schiele_Selfportrait_Male nude in profile, facing left_1910

ZP_Egon Schiele_Selfportrait_Male nude in profile, facing left_1910

.

Strange Austrian “wunderkind” Egon Schiele was the son of a railroad station-master in Tulln and a mother from Krumau in Bohemia (Czechoslovakia). Schiele began to draw at the age of 18 months, and was disturbingly precocious when it came to early explorations of his own sexuality. Schiele’s paintings and drawings are always – unmistakably – his, and the artist died on this day (October 31st) in 1918, at the age of 28. One of the many millions who succumbed to the ineptly-named “Spanish Flu” pandemic which began in January 1918 – before the end of what was then known as The Great War – and lasted until December 1920 – Schiele’s art had had, even before the War, so much of Death about it – and yet also of Eros, and of Love. One of the artist’s own poems – and he did write a handful of them to accompany several canvases – states simply: Ich bin Mensch, ich liebe / Den Tod und Liebe / Das Leben. “I am a human being – I love Death and Love – they are alive.” Schiele’s wife Edith, six months pregnant, died of the “Spanish Flu” on October 28th, 1918, and Schiele, himself already extremely ill, made several sketches of her as she lay dying. He was gone just three days later.

.

Translators Will Stone and Anthony Vivis wrote, in an issue of The London Magazine: “In one of his untitled poems Schiele talks of a bird where ‘a thousand greens are reflected in its eyes’. That this was written by an artist of Schiele’s calibre infuses the image with added significance. Who but he could know the shade created by a thousand greens and hold it long enough to record? What matters is not literally that a thousand greens reflect in the bird’s eye, but the possibility that they could. The green of the eye is so overwhelming that in his determination to see truth above all else the precocious poet-artist has glutted himself with a thousand variations within a single colour. While admitting the impossibility of capturing the reality of nature – like a translator faced with a text which appears to defy intra-linguistic interpretation – Schiele takes up the challenge nevertheless. It is a microcosm of the artistic calling: proceeding with creation and conceding defeat at the same moment. The sense of precariousness, the constant wavering of the boundary between lucidity and excruciation, is perhaps why Schiele’s paintings score so deeply into us even today [April 2012].”

.

The Viennese, bourgeois-art-appreciating public had found Schiele’s un-pretty style and colour palette – often there were grey-green hues for skin, as if the living were putrefying – and his candid, awkward-limbed sexuality / unflattering poses / the angst *of his nudes – difficult to look upon. Yet he was really a proto–Expressionist who was leading the way for Expressionism** – that most powerful German artistic movement of the first quarter of the 20th century. Schiele’s influences were Vincent Van Gogh, “Art-Nouveau”, and Gustav Klimt – all from his boyhood – but it’s the poets, not visual artists, of the decade from 1910 forward, that explored – like Schiele was doing – similar discomfiting emotional and psychological “territories”. And so, we have placed a selection of their verses alongside poems of and images of paintings and drawings by Egon Schiele.

.

* Angst is a great-sounding word. It reached German – and English – via the Danish language and an 1844 treatise by the philosopher Kierkegaard. Angst means Existential anxiety or fear.

** German Expressionism – a definition from Ruth J. Owen:

“A Modernist mode, mainly in the second decade of the 20th century; perspective of angst and absurdity; disturbing visions of downfall and decay; pathological world of the crippled and insane, and images of the city and war. ‘Aufbruch’ (an awakening or departure from) becomes ubiquitous – a new era; dislocated colour, shrill tone; the grotesque, deathliness and dissolution.”

. . .

Egon Schiele (1890-1918)

“Ein Selbstbild” / “Self-Portrait” (1910)

.

Ich bin für mich und die, denen

Die durstige Trunksucht nach

Freisein bei mir alles schenkt,

und auch für alle, weil alle

ich auch Liebe, – Liebe

.

Ich bin von vornehmsten

Der Vornehmste

Und von Rückgebern

Der Rückgebigste

.

Ich bin Mensch, ich liebe

Den Tod und Liebe

Das Leben.

. . .

Egon Schiele

“Sensation”

.

High vast winds turned my spine to ice

and I was forced to squint.

On a scratchy wall I saw

the entire world

with all its valleys, mountains and lakes,

with all the animals running around

shadows of trees and the patches of sun

reminded me of clouds.

I strode upon the earth

and had no sense of my limbs

I felt so light.

. . .

“Empfindung”

.

Hohe Grosswinde machten kalt mein Rückgrat

und da schielte ich.

Auf einer krätzigen Mauer sah ich

die ganze Welt

mit allen Tälern und Bergen und Seen,

mit all den Tieren, die da umliefen –

Die Schatten der Bäume und die Sonnenflecken erinnerten

mich an die Wolken.

Auf der Erde schritt ich

und spürte meine Glieder nicht,

so leicht war mir.

. . .

Egon Schiele

“Music while drowning”

.

In no time the black river yoked all my strength

I saw the lesser waters great

and the soft banks steep and high.

.

Twisting I fought

and heard the waters within me,

the fine, beautiful black waters –

then I breathed golden strength once more.

The river ran rigid and more strongly.

. . .

“Musik beim ertrinken”

.

In Momenten jochte der schwarze Fluss meine ganzen Kräfte.

Ich sah die kleinen Wasser gross

Und die sanften Ufer steil und hoch.

.

Drehend rang ich

und hörte die Wasser in mir,

die guten, schönen Shwarzwasser –

Dann atmete ich wieder goldene Kraft.

Der Strom strömte starr und stärker.

.

Egon Schiele’s poems: translations from the German © Will Stone and Anthony Vivis

. . .

Else Lasker-Schüler (1869-1945)

“Oh, let me leave this world”

.

Then you will cry for me.

Copper beeches pour fire

On my warlike dreams.

Through dark underbrush

I crawl,

Through ditches and water.

Wild breakers beat

My heart incessantly;

The enemy within.

Oh let me leave this world!

But even from far away

I’d wander – a flickering light –

Around God’s grave.

. . .

“O ich möcht aus der Welt”

.

Dann weinst du um mich.

Blutbuchen schüren

Meine Träume kriegerisch.

Durch finster Gestrüpp

Muß ich

Und Gräben und Wasser.

Immer schlägt wilde Welle

An mein Herz;

Innerer Feind.

O ich möchte aus der Welt!

Aber auch fern von ihr

Irr ich, ein Flackerlicht

Um Gottes Grab.

. . .

. . .

|

Gottfried Benn (1886-1956) D-Zug Braun wie Kognak. Braun wie Laub. Rotbraun. Malaiengelb. |

Gottfried Benn Express Train Brown as cognac. Brown as leaves. Red-brown. Malayan yellow. . (1912) Translation from the German © Michael Hamburger |

|

Gottfried Benn Vor Einem Kornfeld Vor einem Kornfeld sagte einer: |

Gottfried Benn Before a Cornfield Before a cornfield he said: . (1913) Translation from the German © SuperVert |

.

Georg Heym (1887-1912)

“Umbra vitae”

.

Die Menschen stehen vorwärts in den Straßen

Und sehen auf die großen Himmelszeichen,

Wo die Kometen mit den Feuernasen

Um die gezackten Türme drohend schleichen.

Und alle Dächer sind voll Sternedeuter,

Die in den Himmel stecken große Röhren.

Und Zaubrer, wachsend aus den Bodenlöchern,

In Dunkel schräg, die einen Stern beschwören.

Krankheit und Mißwachs durch die Tore kriechen

In schwarzen Tüchern. Und die Betten tragen

Das Wälzen und das Jammern vieler Siechen,

und welche rennen mit den Totenschragen.

Selbstmörder gehen nachts in großen Horden,

Die suchen vor sich ihr verlornes Wesen,

Gebückt in Süd und West, und Ost und Norden,

Den Staub zerfegend mit den Armen-Besen.

Sie sind wie Staub, der hält noch eine Weile,

Die Haare fallen schon auf ihren Wegen,

Sie springen, daß sie sterben, nun in Eile,

Und sind mit totem Haupt im Feld gelegen.

Noch manchmal zappelnd. Und der Felder Tiere

Stehn um sie blind, und stoßen mit dem Horne

In ihren Bauch. Sie strecken alle viere

Begraben unter Salbei und dem Dorne.

Das Jahr ist tot und leer von seinen Winden,

Das wie ein Mantel hängt voll Wassertriefen,

Und ewig Wetter, die sich klagend winden

Aus Tiefen wolkig wieder zu den Tiefen.

Die Meere aber stocken. In den Wogen

Die Schiffe hängen modernd und verdrossen,

Zerstreut, und keine Strömung wird gezogen

Und aller Himmel Höfe sind verschlossen.

Die Bäume wechseln nicht die Zeiten

Und bleiben ewig tot in ihrem Ende

Und über die verfallnen Wege spreiten

Sie hölzern ihre langen Finger-Hände.

Wer stirbt, der setzt sich auf, sich zu erheben,

Und eben hat er noch ein Wort gesprochen.

Auf einmal ist er fort. Wo ist sein Leben?

Und seine Augen sind wie Glas zerbrochen.

Schatten sind viele. Trübe und verborgen.

Und Träume, die an stummen Türen schleifen,

Und der erwacht, bedrückt von andern Morgen,

Muß schweren Schlaf von grauen Lidern streifen.

. . .

Georg Heym

“Umbra vitae” (The Shadow of Life)

.

The people stand forward in the streets

They stare at the great signs in the heavens

Where comets with their fiery trails

Creep threateningly about the serrated towers.

And all the roofs are filled with stargazers

Sticking their great tubes into the skies

And magicians springing up from the earthworks

Tilting in the darkness, conjuring the one star.

Sickness and perversion creep through the gates

In black gowns. And the beds bear

The tossing and the moans of much wasting

They run with the buckling of death.

The suicides go in great nocturnal hordes

They search before themselves for their lost essence

Bent over in the South and West and the East and North

They dust using their arms as brooms.

They are like dust, holding out for a while

The hair falling out as they move on their way,

They leap, conscious of death, now in haste,

And are buried head-first in the field.

Yet occasionally they twitch still. The animals of the field

Blindly stand around them, poking with their horn

In the stomach. They lie on all fours

Buried under sage and thorn.

The year is dead and emptied of its winds

That hang like a coat covered with drops of water

And eternal weather, which bemoaning turns

From cloudy depth again to the depths.

But the seas stagnate. The ships hang

Rotting and querulous in the waves,

Scattered, no current draws them

And the courts of all heavens are sealed.

The trees fail in their seasonal change

Locked in their deadly finality

And over the decaying path they spread

Their wooden long-fingered hands.

He who dies undertakes to rise again,

Indeed he just spoke a word.

And suddenly he is gone. Where is his life?

And his eyes are like shattered glass.

Many are shadows. Grim and hidden.

And dreams which slip by mute doors,

And who awaken, depressed by other mornings,

Must wipe heavy sleep from greyed lids.

.

(1912)

.

Heym translation © Scott Horton

. . . . .

ZP_Egon Schiele_photographed at the age of 24 by Anton Josef Trcka_1914

ZP_Egon Schiele_photographed at the age of 24 by Anton Josef Trcka_1914

.

Images (paintings and drawings) featured here:

Egon Schiele_Selfportrait_Male nude in profile, facing left_1910

Egon Schiele_Selfportrait with arm twisted above head_1910

Egon Schiele_Reclining male nude_1911

Egon Schiele_Composition with three male figures_Selfportrait_1911

Egon Schiele_Male nude with a red loincloth_1914

Egon Schiele_Sitzender weiblicher Akt_Female nude sitting_1914

Egon Schiele_Death and the Maiden_1915

Egon Schiele_Sitzende frau mit hochgezogenem knie_The model was – possibly – Wally Neuzil (1894 – 1917). Neuzil was a former model for Gustav Klimt and she became Schiele’s model / muse / lover before his marriage to Edith Harms.

Egon Schiele_Reclining woman with green stockings_Adele Harms_1917

Egon Schiele_Embrace_Lovers II_1917

Egon Schiele_Edith sterbend_Edith dying_October 28th 1918_the last drawing by Schiele

. . . . .

Alicia Claudia González Maveroff: “Verdun”

Posted: October 21, 2013 Filed under: Alicia Claudia González Maveroff, English, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Alicia Claudia González Maveroff: “Verdun”Alicia Claudia González Maveroff

“Verdun”

.

And now that I’m going, now that I depart,

now that autumn will be my spring;

yes, now that I’m going, I know that for always

I will carry within me

this river, and this autumn red

in the pupil of my eye.

Well, now that I go, knowing that

tomorrow I journey through another river,

perhaps seeking that “bonanza” of calm

that rivers just don’t have because

they “walk fast – and keep moving…”;

in my soul the memory remains –

of the river, road, bridge;

those autumn colours – red, yellow –

painted among the trees.

I had already loved before, long before,

many landscapes, blue skies, other trees…

But – here today –

I loved this river, this bridge and this road;

these trees – red and yellow –

painted by autumn.

.

(Toronto, Canada, 21-10-2011)

. . .

“Verdun”

.

Y ahora que me voy, ahora que parto,

ahora que el otoño será mi primavera,

ahora que me voy, sé que por siempre,

seguro llevaré este río en mi memoria

y el rojo del otoño en mis pupilas.

Bien, ahora que me voy, sabiendo

que caminaré mañana en otro río,

tal vez lo haga buscando yo “la calma”

que el agua de los ríos no la tiene,

porque “caminan fuerte y siempre pasan”.

Más quedan en mi alma, los recuerdos,

el río, el camino, el puente

el rojo y amarillo del otoño,

pintado entre los árboles.

Yo ya había amado antes:

amé muchos paisajes, hace tiempo,

amé cielos celestes y otros árboles…

Pero hoy aquí, yo amé:

este rió, este puente, este camino

y estos árboles de rojo y amarillo

pintados en otoño…

.

(Toronto, Canadá, 21-10-2011)

. . .

Preguntamos al poeta: Que es el significado del título del poema?

Y ella nos dijo:

Te comento que el poema se llama “Verdun” por el barrio de Montréal, Québec. Allí viví cuando visité Canadá y me enamoré de este país. El poema lo escribí en Toronto, mientras paseaba, para dejárselo a la amiga que visité. Esta es la historia de porque el nombre. Caminábamos cerca del río San Lorenzo, en Verdun, mirando el río, pasábamos por un puente rojo y gris y los árboles otoñales estaban pintados de rojo y amarillo, como describo en el poema. En el final del mismo dice “…yo ya había amado antes: amé muchos paisajes hace tiempo, amé cielos celestes y otros árboles…”

Aquí hago referencia a otro sitio, en la otra punta del mapa; hablo de otro río – el “Bug” en Polonia, donde he estado muchas veces (es uno de “mis sitios en el mundo” – y tengo algunos otros en mi corazón.) Allí también caminaba junto al río, en la campiña polaca, cerca de hermosos bosques y con bellos cielos, casas campesinas con techos negros de paja (algo bellisímo), diferente para mí que vivo en Buenos Aires, en el “Fin del Mundo” (como dice el Papa Francisco.) Pero ya entonces mis amigos polacos me decían que yo venia “del fin del mundo”, aunque al estar allí en Polonia, yo en broma les decía que yo estaba visitando “el fin del mundo…” Te confieso que no he encontrado el fin del mundo, por más que recorro no logro hallarlo. Curiosamente, el nombre de este río polaco que llega desde Rusia a Polonia quiere decir Dios, tal vez sea Él quien me lleve por estos lugares…¿? Lo cierto es que son lugares que están en mí por lo que he podido experimentar…

. . .

We asked the poet to talk about the name of her poem – Verdun. Here’s what Alicia told us:

“Verdun is after the Montreal borough of the same name. I lived there when I visited Canada – and fell in love with the country. The poem itself I wrote in Toronto, while passing through, to leave for the friend I’d visited. … So, in Montreal (Verdun) we were walking alongside the St. Lawrence River and we passed by a red and grey bridge, and there were autumn trees with leaves all yellow and red. After seeing this there came into my mind these words: “I had already loved before, long before, many landscapes, blue skies, other trees…” I was thinking then of another place, another point, on the map, and another river – the River “Bug” in Poland. I’ve been there many times – it’s one of my special places in this world – and I have a few others, too, in my heart. So I was walking along the “Bug”, in the Polish countryside, close to lovely woods, and a pretty sky overhead, and the rural houses with their black straw roofs – something so beautiful – and quite different for someone like me who lives in Buenos Aires (at “the End of the Earth”, as Pope Francis says.) I confess that I’ve yet to encounter “the End of the Earth”; as much as I’ve traversed the globe I haven’t attained such a feat! Oddly, the name of that Polish river – “Bug” – that flows between Russia and Poland – is supposed to mean “God”…and maybe it’s He who carries me to all these various places…? One thing’s certain: these places are “within me”, too, and I’ve been able to experiment with them…”

. . .

Translations from Spanish into English: Alexander Best