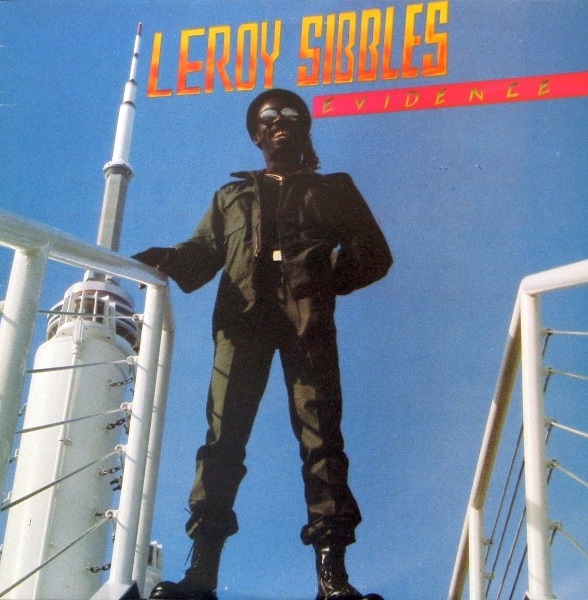

Toronto Reggae History Project: 1972-1987

Posted: February 10, 2015 Filed under: IMAGES | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Toronto Reggae History Project: 1972-1987 Visit Reggae Toronto at

Visit Reggae Toronto at

http://reggaetoronto.com/

Cumpleaños de Bob Marley: “400 años” y “Tontos tercos”

Posted: February 6, 2015 Filed under: Bob Marley, English, Spanish | Tags: Black History Month, El Mes de la Historia Afroamericana Comments Off on Cumpleaños de Bob Marley: “400 años” y “Tontos tercos”400 años, una canción de Peter Tosh, del album “Catch a Fire” (“Coge un Fuego”), grabado en 1973 por Bob Marley & The Wailers (“Los Plañideros”):

. . .

400 years, 400 years, 400 years…Wo-o-o-o,

And it’s the same philosophy.

I’ve said it’s four hundred years, 400 years, 400 years…Wo-o-o-o,

Look, how long!

And the people they still can’t see.

Why do they fight against the poor youth of today?

And without these youths, they would be gone, all gone astray.

.

Come on, let’s make a move, make a move, make a move…Wo-o-o-o,

I can see time, the time has come.

And if a-fools don’t see, fools don’t see, fools don’t see…Wo-o-o-o,

I can’t save the youth.

But the youth is gonna be strong!

So, won’t you come with me?

I’ll take you to a land of liberty

Where we can live – yes, live a good, good life,

And be free.

.

Look how long! (400 years, 400 years, 400 years…)

Way too long! (Wo-o-o-o…)

That’s the reason my people, my people can’t see.

Said: it’s four hundred long years (400 years, 400 years. Wo-o-o-o)

Give me patience – and it’s the same philosophy.

.

It’s been 400 years, 400 years, 400 years…

Wait so long! Wo-o-o-o,

How long?

400 long, long years…

. . .

400 años, 400 años, y seguimos teniendo la misma filosofía…

Yo he dicho que es 400 años, 400 años, y todavía la gente no ve más allá…

¿Por qué luchar contra los pobres jóvenes de hoy?

Sin ellos hoy estarían todos yendo por el mal camino…

Vamos, movámonos, la hora ha llegado, y aunque los tontos no lo ven como salvar a la juventud – pero ellos son fuertes…

Entonces, ¿por qué no vienes conmigo? Te llevaré a un lugar – la tierra de la libertad – donde podremos vivir bien y ser libres…

Mira – tan largo – 400 años, 400 años, tanto tiempo que no pueden ver más allá…

400 años, 400 años…Dame paciencia…la misma filosofía…

Hemos atravesado 400 años – hemos esperado tanto tiempo…largos años…

. . .

La frase 400 años hace referencia al principio del comercio de la esclavitud africana (durante el siglo XVI.) El primero ingenio azucarero jamaicano fue fundado en Sevilla La Nueva (cerca de Bahía Santa Ana) por los Españoles durante su periodo colonizador (1509–1655) en “Santiago” (el primero nombre castellano para Jamaica). En hecho, es la mayoría de Jamaicanos que son descendientes de esos esclavos…

Para leer otras letras de Bob Marley & The Wailers que se tratan de liberarse de las formas diversas de la esclavitud, cliquea en el enlace:

https://zocalopoets.com/2013/02/06/mind-is-your-only-ruler-sovereign-marcus-garvey-and-bob-marley-emancipense-de-la-esclavitud-mental-nadie-mas-que-nosotros-puede-liberar-nuestras-mentes/

. . . . .

Stiff-necked Fools (1980/1983)

.

Stiff-necked fools, you think you are cool

To deny me for simplicity.

Yes, you have gone for so long

With your love for vanity now.

Yes, you have got the wrong interpretation

Mixed up with vain imagination.

.

So take Jah Sun, and Jah Moon,

And Jah Rain, and Jah Stars,

And forever, yes, erase your fantasy, yeah!

.

The lips of the righteous teach many,

But fools die for want of wisdom.

The rich man’s wealth is in his city;

The righteous’ wealth is in his Holy Place.

So take Jah Sun, and Jah Moon,

And Jah Rain, and Jah Stars,

And forever, yes, erase your fantasy, yeah!

Destruction of the poor is in their poverty;

Destruction of the soul is vanity, yeah!

.

So stiff-necked fools, you think you are cool

To deny me for simplicity, yeah!

Yes, you have gone, gone for so long

With your love for vanity now.

.

But I don’t wanna rule ya!

I don’t wanna fool ya!

I don’t wanna school ya,

Things you might never know about!

.

Yes, you have got the wrong interpretation

Mixed up with vain imagination…

Stiff-necked fools, you think you are cool

To deny me for, ooh-ooh, simplicity!

. . .

Stiff-necked Fools: Marley has used phrases from The Bible in this song, particularly Proverbs 10, verses 15 and 21.

The Battle of Adwa fought in 1896 was the climactic confrontation of the First Italo-Ethiopian War, and it secured Ethiopian sovereignty. Painting from the collection of the Tropenmuseum in The Netherlands_Una representación de la victoria etíope contra los italianos en la Batalla de Adwa (1896).

El imperio de Etiopía quedó independiente durante la era de dominio européo en África; este hecho histórico fue de suma importancia al nacimiento de un movimiento afro-caribeño cuasi-bíblico: el Rastafarianismo. Robert Nesta Marley permanece el “Rasta” más famoso mundial.

Tontos tercos

.

Tontos tercos, piensan que son ‘cool’

para negarme la simplicidad.

Sí, tu te has ido por largo tiempo

Con tu amor por vanidad ahora.

Sí, tu tienes mala interpretación

Mezclada con vana imaginación.

.

Así que toma el Sol de Jah, la Luna de Jah y la Lluvia de Jah, las Estrellas de Jah,

Y para siempre, sí, borra tu fantasía, yeah-yeah.

.

Los labios del justo enseñan a muchos,

Pero los necios mueren por falta de entendimiento.

La riqueza del hombre rico está en su ciudad;

La riqueza de los justos está en su santo lugar.

.

Así que toma el Sol de Jah, la Luna de Jah y la Lluvia de Jah, las Estrellas de Jah,

Y para siempre, sí, borra tu fantasía, yeah-yeah.

La destrucción de los pobres esta en su pobreza;

¡La destrucción del alma es la vanidad, sí!

.

Entonces, tontos tercos, piensan que son ‘cool’

Para negarme la simplicidad, yeah-yeah.

Sí, tu te has ido por largo tiempo

Con tu amor por vanidad ahora.

¡Pero yo no quiero ya las reglas!

¡No quiero ser tonto ya!

Yo no quiero ya la escuela:

Cosas tuyas..¡puede ser que nunca sepamos de ellas!

.

Sí, tienen mala interpretación

Mezclada con vana imaginación…

Tontos tercos, ¡piensan que son ‘cool’

Para negar a mí, ooh-ooh, la simplicidad!

. . .

Marley utiliza unas frases biblicas en sus letras aqui: por ejemplo, Proverbios 10, versos 15 y 21.

. . .

Bob Marley & The Wailers: “Stiff-necked Fools” / “Tontos tercos” fue grabado en 1980 y lanzado póstumamente, en 1983. Puede oír el sonido frágil de la voz de Marley, porque sufría del cáncer que pronto le mataría…

http://youtu.be/0sBrvhMeGlw

.

Retrato en lo alto por Bruce Patrick Jones: Silueta de Robert Nesta Marley (1945-1981)

. . . . .

Jamaica Omnibus Services: “The Rhymes of Jolly Joseph” / Las Rimas de José “El Jovial”

Posted: February 6, 2015 Filed under: English | Tags: Black History Month, El Mes de la Historia Afroamericana Comments Off on Jamaica Omnibus Services: “The Rhymes of Jolly Joseph” / Las Rimas de José “El Jovial”

A vintage Jamaica Omnibus ticket_dimensions 1.5 inches by 2.5 inches_au verso is printed Courtesy Makes Life Smooth. The fare price, printed in pounds sterling, denotes a 1960s ticket, before the switch to a Jamaican dollar currency.

Bruce Patrick Jones remembers the Jamaica Omnibus Services: “The Rhymes of Jolly Joseph”

. . .

I remember, I remember,

The house where I was born,

The little window where the sun

Came peeping in at morn…

.

So begins Thomas Hood’s poem of memories.

In the 1960s, poetry was an essential inclusion in Jamaican Secondary School education. Simple, rhyming poems have always been the most accessible and sweetest examples of what remains, for me, a mysterious and enigmatic art form. Couplets, with their natural sing-song sway, easily pull a reader into their world, guiding them to the more complex forms of poetic writing.

A bus ride on a recent visit home to Jamaica jolted back a memory from my early teen years. Back then, the Jamaica Omnibus Service (JOS) was essential to the transportation of the citizens of Kingston. Advertising promotion affectionately named the bus line “Jolly Joseph”, and each vehicle was operated by a driver, usually male, and a conductor or conductress, almost always female. As riders entered the bus by a rear side door and paid their fares, the conductor would issue the appropriate ticket for the requested journey. Tickets were rectangular, printed in black on light card of various colours. On one side was the fare price and on the other, rhyming couplets with a variety of messages to aid the rider. Of these, two came clearly back to mind:

.

To stop the bus hold out your hand,

The driver then will understand.

.

And, to address easy loading:

.

If at the stop you form a queue,

We’ll all get on, including you.

.

The latter was great on over-promise, as the exploding population of Kingston began to put a heavy burden on infrastructure in those days.

I’ve thought hard and long trying to remember the other rhymes, and dream that one day I might find an old JOS ticket doing duty as a bookmark or hidden away in a drawer, ready to help me make the leap to Keats and Wordsworth.

. . .

. . . . .

Bruce Patrick Jones: Recuerdos del Servicio de Autobuses Jamaicanos (JOS)

.

Las Rimas de José “El Jovial”

.

“Recuerdo, recuerdo, la casa donde yo nací,

y la pequeña ventana donde llega con su miradita el sol,

cada mañana…”

Y bien inicia Thomas Hood su poema de memorias…

.

Durante los años 1960, la poesía era una inclusión esencial por la educación secundaria jamaicana.

Simples coplas rimadas siempre han sidos los ejemplos más dulces – y alcanzables – de lo que queda, para mí, una forma de arte tan misteriosa y enigmática. Coplas, con su bamboleo y sonsonete natural, atraen en su mundo el lector, guiándole hacia la poesía más compleja.

.

Un aventón en autobus durante una visita reciente a mi país natal me impresionó un recuerdo de mi adolescencia. En esos años del décado 1960, El Servicio de Autobuses Jamaicanos (JOS) era un sistema esencial en la vida de los ciudadanos de Kingston (la capital).

Anuncios dieron al autobus el apodo José “El Jovial”, y cada vehículo tuvo un conductor manejando y una conductora – casi siempre una conductora – que expedía los billetes apropriados por el viaje pedido. Los billetes eran rectangulares, de tarjeta liviana de varios colores, imprimido con tinta. En un lado apareció el precio y en el otro: coplas rimadas. Puedo recordar dos ejemplos:

.

Para detener el bus – estira la mano,

El conductor – pues – va entenderlo.

.

Y una rima que trata sobre el tema del abordaje fácil:

.

Si en la parada hacemos la cola,

Vamos avanzar – todos – cada en fila.

.

La segunda fue pesado con una promesa casi imposible, a causa de la población explotando de Kingston durante esa era; la infraestructura de la ciudad se volvía muy cargada.

.

Yo he reflexionado mucho sobre estas “poemitas”, y es mi sueño que descubriré, algún día, un billete viejo de JOS que está sirviendo como marcalibros – o escondiendo en un cajón – ¡listo para ayudarme saltar al mundo de Keats y Wordsworth!

Bruce Patrick Jones es un artista gráfico, nacido en Jamaica en 1949. Ha vivido en Toronto, Canadá, desde 1971. / Bruce Patrick Jones is a Jamaican-born graphic artist who has lived in Toronto, Canada, since 1971.

. . . . .

Marcus Garvey: “Those Who Know”

Posted: February 6, 2015 Filed under: English, Marcus Garvey | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Marcus Garvey: “Those Who Know” Marcus Mosiah Garvey (1887-1940, born Saint Ann’s, Jamaica) was a Black Renaissance Man: energetic, intense, full of creative ideas – and “all over the map”. A political leader, prosyletizer, journalist, publisher, and all-round entrepreneur, he was most especially a passionate, moralizing orator.

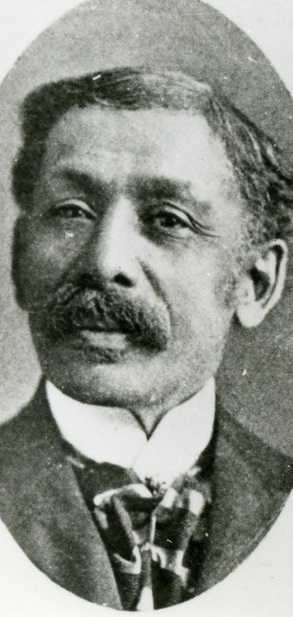

Marcus Mosiah Garvey (1887-1940, born Saint Ann’s, Jamaica) was a Black Renaissance Man: energetic, intense, full of creative ideas – and “all over the map”. A political leader, prosyletizer, journalist, publisher, and all-round entrepreneur, he was most especially a passionate, moralizing orator.

Dusé Mohamed Ali (1866-1945), the Egyptian-Sudanese founder of the African Times and Orient Review (in London in 1912) was one of Garvey’s mentors during the Jamaican’s time in England; Garvey’s pan-African and Black Nationalist thrust owed much to Ali’s example.

Though Garvey found himself on the wrong side of the NAACP’s W.E.B. DuBois (calling DuBois’ mulatto-ness “a monstrosity” ) and on the right side of Edward Young Clarke (Imperial Wizard of the KKK) – “repatriation” of “Africans” from the U.S.A. “back to” Liberia being the agreed goal – still, Garvey’s legacy has been much more solid than the sometimes madcap careenings of his tumultuous life.

However one perceives, weighs, accepts or judge’s this complex thinker’s worldview, Garvey nevertheless gives good advice to all of us in the following poem…

. . .

Marcus Mosiah Garvey (1887-1940)

“Those Who Know”

.

You may not know, and that is all

That causes you to fail in life;

All men should know, and thus not fall

The victims of the heartless strife.

Know what? Know what is right and wrong,

Know just the things that daily count,

That go to make all life a song,

And cause the wise to climb the mount.

.

To make man know, is task, indeed,

For some are prone to waste all time:

It’s only few who see the need

To probe and probe, then climb and climb.

The midnight light, the daily grind,

Are tasks that count for real success

In life of those not left behind,

Whom Nature chooses then to bless.

.

The failing men you meet each day,

Who curse their fate, and damn the rest,

Are just the sleeping ones who play

While others work to reach the best.

All life must be a useful plan,

That calls for daily, serious work –

The work that wrings the best from man –

The work that cowards often shirk.

.

All honour to the men who know,

By seeking after Nature’s truths.

In wisdom they shall ever grow,

While others hum the awful ‘blues’.

Go now and search for what there is –

The knowledge of the Universe.

Make it yours, as the other, his;

And be as good, but not the worse.

. . . . .

Image: Bruce Patrick Jones: Silhouette of Marcus Garvey

Maya Angelou: “La vida no me asusta…” / “Life doesn’t frighten me”

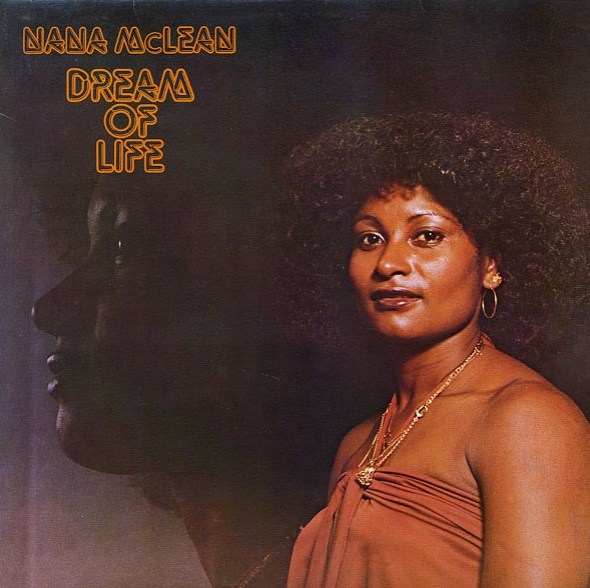

Posted: February 5, 2015 Filed under: English, Maya Angelou, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: Black History Month, Jean-Michel Basquiat Comments Off on Maya Angelou: “La vida no me asusta…” / “Life doesn’t frighten me”Maya Angelou (born Marguerite Annie Johnson, 1928-2014)

Life doesn’t frighten me (1993)

.

Shadows on the wall, noises down the hall,

Life doesn’t frighten me at all.

Bad dogs barking loud, big ghosts in a cloud,

That doesn’t frighten me at all.

.

Mean old Mother Goose, lions on the loose,

They don’t frighten me at all.

Dragons breathing flame on my counterpane,

That doesn’t frighten me at all.

.

– I go Boo, make them shoo,

I make fun, a-waaay they run!

I won’t cry, so they fly,

I just smile, and they go wild!

Life doesn’t frighten me at all.

.

Tough guys in a fight, all alone at night,

Life doesn’t frighten me at all.

Panthers in the park, strangers in the dark,

No, they don’t frighten me at all.

.

That new classroom where

Boys all pull my hair,

They don’t frighten me – at all.

Kissy little girls

With their hair in curls,

They don’t frighten me – at all.

.

Don’t show me frogs and snakes

And listen for my screams

– IF I’m afraid at all,

It’s ONLY in my dreams…

.

I have got a magic charm that I keep up my sleeve,

I can walk the ocean floor and never have to breath.

Life doesn’t frighten me – not at all – not at all,

Life doesn’t frighten me at all.

. . .

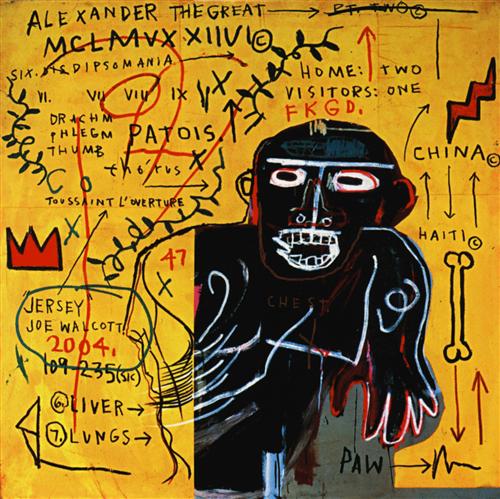

“Life doesn’t frighten me”, Maya Angelou’s children’s poem paired posthumously with paintings by Jean-Michel Basquiat, was published in 1993 by Stewart, Tabori & Chang press (editor Sara Jane Boyers).

Maya Angelou (1928-2014)

“La vida no me asusta…”

.

Sombras en la pared, ruidos abajo el corredor,

no, esta vida no me da miedo – ni una pizca.

Perros malos que ladran tan altos, fantasmas en una nube

– no, esos no me asustan, para nada.

.

La infame Mamá Ganso, y leones cuando están sueltos,

no me dan miedo, sí – no me dan miedo.

Dragones que respiran la llama…sobre mi ventanilla,

no, esto no me asusta – ni una pizca.

Digo: ¡Bu! Y los ahuyento.

Los burlo de ellos ¡y huyen!

No voy a llorar, ¡pues se echan a volar!

Solo sonrío – ¡y se vuelven locos!

La vida no me da miedo, de veras.

.

Matones en una pelea, solitaria en la noche,

La vida no me asusta – ni una pizca.

Panteras en el parque, desconocidos en la oscuridad,

no, ellos no me dan miedo, ah no.

.

Esa nueva aula donde los chicos jalan mi cabello,

Ellos no me dan miedo – ni una pizca.

Chicas cursis con su pelo chino,

no, ellas no me asustan, para nada.

.

No me mostras ranas y culebras

– pues esperar mis gritos…

SI yo tenga miedo – quizás –

SOLO exista en mis sueños…

.

Poseo un amuleto mágico que guardo en la manga,

Puedo caminar por el suelo marino y nunca no tengo que respirar.

Esta vida no me da miedo – ni una pizca – para nada,

no, la vida no me asusta, ah no.

. . .

“La vida no me asusta” es un poema de Maya Angelou escrito para niños, y emparejado póstumamente con unas pinturas de Jean-Michel Basquiat (“la estrella fugaz” del mundo-arte en los años 80). Fue publicado en 1993 por Stewart, Tabori & Chang (editor: Sara Jane Boyers).

. . . . .

Jean-Michel Basquiat: Now’s The Time…

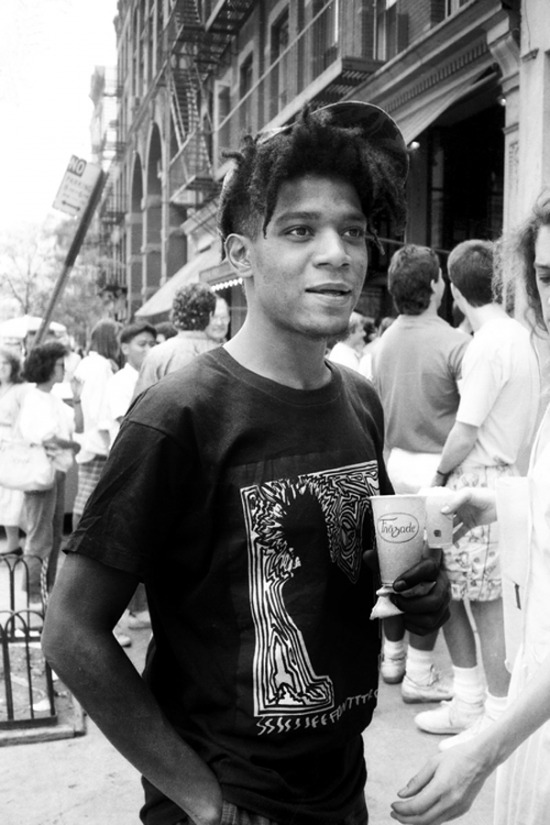

Posted: February 5, 2015 Filed under: English | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Jean-Michel Basquiat: Now’s The Time…In conjunction with a retrospective exhibition opening this week at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Canada…

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) was a “shooting-star” phenomenon of the New York City art scene during the 1980s. In less than a decade he zoomed from teenage magic-marker-on-walls graffiti punk – from 1977 to 1980 – under the name SAMO © (Same Old Shit Copyright) with fellow high-schoolers Al Diaz, Shannon Dawson, and Matt Kelly – to major Manhattan trendy. The enigmatic poetic thoughts and slogans of SAMO found their way onto Basquiat’s canvases, and his SAMO “tagging” years in SoHo and Lower Manhattan can be viewed as a kind of early advertisement for himself as an Artist.

.

One of three children born to Gérard Basquiat, from Haiti, and Matilde Andrades, Brooklyn-born but of Puerto-Rican descent, Jean-Michel’s home life was unstable, his mother being institutionalized from the time he was 11 years old, and his father banishing him from about the age of 15 after he dropped out of school following Grade 10. However, his mother’s gift to him of a copy of Gray’s Anatomy, the 1858 illustrated encylopaedia of the human body, before he was ten years old, planted in him the seed of ambition for future artistic expression.

.

The late 1970s-early 1980s New York City confluence of street culture with art, via the emerging rap (later “hip-hop”) and graffiti scenes, plus his interest in a “serious” art career, helped to position Basquiat for stardom; he was, in fact, in the right place at the right time.

.

Keith Haring, two and a half years older, would take the NYC graffiti phenomenon in a whole other Street Meets the PopArt World direction during the 1980s, whereas Basquiat aimed for a more painterly self-expression, fashioning a synthesis of Primitivism and Neo-Expressionism on canvas initiated through his graffiti and “tagging” origins.

.

In February of 1985, Basquiat appeared on the cover of The New York Times Magazine in a feature titled “New Art, New Money: The Marketing of an American Artist”.

.

http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/08/09/specials/basquiat-mag.html

.

He was both successful and very “Now” by then, yet his growing appetite for heroin use was beginning to interfere with his friendships and professional obligations. Though he did attempt to kick his heroin habit, he ultimately died of an overdose in his Great Jones Street studio in August of 1988. He was 27 years old.

At the artist’s funeral, rap/hiphop pioneer Fab Five Freddy read the following poem:

“Genius Child” by Langston Hughes

.

This is a song for the genius child,

Sing it softly, for the song is wild.

Sing it softly as ever you can,

Lest the song get out of hand.

Nobody loves a genius child,

Can you love an eagle,

Tame or wild?

Can you love an eagle,

Wild or tame?

Can you love a monster

Of frightening name?

Nobody loves a genius child.

Kill him – and let his soul run wild.

.

.

Of Basquiat’s worldview, artist Lydia Lee has said:

“Like a DJ, he adeptly reworked the clichéd language of gesture, freedom, and angst in Neo-Expressionism, and redirected Pop Art’s strategy of appropriation, in order to produce a body of work that at times celebrated Black culture and history, yet also revealed its complexity and contradictions.”

.

In 2005, Marc Mayer, a curator and art historian, wrote of Basquiat the artist:

“Basquiat speaks articulately while dodging the full impact of clarity like a matador. We can read his pictures without strenuous effort—the words, the images, the colours and the construction—but we cannot quite fathom the point they belabour. Keeping us in this state of half-knowing, of mystery-within-familiarity, had been the core technique of his brand of communication since his adolescent days as a graffiti poet with SAMO©. To enjoy them, we are not meant to analyze the pictures too carefully. Quantifying the encyclopedic breadth of his research certainly results in an interesting inventory, but the sum cannot adequately explain his pictures, which require an effort outside the purview of iconography… He painted a calculated incoherence, calibrating the mystery of what such apparently meaning-laden pictures might ultimately mean.”

. . .

ZP Editor’s Note:

Basquiat’s painting Defacement: The Death of Michael Stewart, references the 1983 beating-into-unconsciousness-then-cardiac-arrest-after-two-weeks-in-a-coma death of a 25-year-old Black graffiti artist (born in Brooklyn in 1958). Though Stewart had resisted arrest for illegal spray-painting, it was significant that he was unarmed, yet eleven White police officers had participated in his “take-down”. An all-White jury later acquitted them.

Recent “racial” happenings indicate – unfortunately – that Basquiat’s painting Defacement still resonates powerfully; occurrences in Ferguson, Ohio, and Staten Island, New York City, both in 2014, are prime examples.

Between 1970 and 2000, the racial demographics of Ferguson, Ohio, shifted dramatically: from 99 percent White to approximately 45 percent White; from 1 percent Black to approximately 52 percent Black. Yet the Ferguson Police Department’s force has remained overwhelmingly White.

In August of 2014, 18-year-old Michael Brown, who was Black, was fatally shot by a White Ferguson police officer, and the use of lethal force was roundly felt to be unwarranted. Looting and riots – yet also peaceful demonstrations – followed, but in November 2014 the police officer responsible was not indicted in the shooting death of the teen. Brown’s death, and the chain of events that followed, have brought to international attention the simmering resentments and inequalities that persist in some American towns and cities.

In July 2014, on Staten Island in New York City, Eric Garner, a Black man, had also died – as a result of a choke-hold around his neck – from a White police officer. Illegally selling cigarettes, yet Garner too was unarmed, and he did not resist arrest; in fact he raised his hands in the air to show that he carried no weapon. Still, he was tackled to the ground, face down, and choke-held. Garner, obese and asthmatic, died. This death was ruled a homicide – yet the impulse by a White police officer to use excessive force on a Black person remains a heated topic, and has sparked a range of national discussions in the U.S.A.

. . . . .

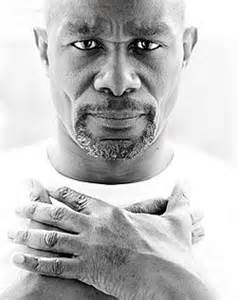

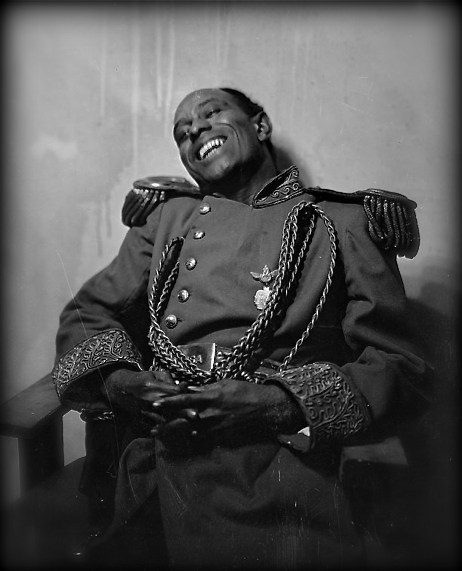

John Douglas Thompson as Joe Mott in Eugene O’Neill’s “The Iceman Cometh”

Posted: February 4, 2015 Filed under: English | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on John Douglas Thompson as Joe Mott in Eugene O’Neill’s “The Iceman Cometh”

Paul Robeson (1898-1976), photographed about 1924, at the time he was starring in Eugene ONeill’s All God’s Chillun Got Wings

Q & A with John Douglas Thompson, who plays Joe Mott in Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh…

An interview by J. Kelly Nestruck, in Toronto’s The Globe & Mail newspaper, February 3rd, 2015:

. . .

The Goodman Theatre’s 2012 production of The Iceman Cometh had one of the most exceptional ensembles in recent stage history. Stratford Festival regulars Brian Dennehy and Stephen Ouimette performed alongside Tony-winner Nathan Lane in director Robert Falls’ painterly production of Eugene O’Neill’s classic 1939 drama about alcoholics chasing pipe dreams in a New York saloon.

.

Less well known to Canadians is their co-star John Douglas Thompson – even though the 51-year-old stage actor grew up on this side of the border. Thompson was stunning as Joe Mott, a former gambling-house operator “whose gentle good humour masks a volcanic rage at a life warped by racism,” according to New York Times critic Charles Isherwood.

In advance of the Iceman remount at the prestigious Brooklyn Academy of Music this month, The Globe and Mail’s theatre critic spoke over the phone with Thompson – who, according to The New Yorker, is “regarded by some as the best classical actor in America.”

.

J. Kelly Nestruck:

I went to Chicago three years ago because I wanted to see Ouimette, Lane and Dennehy. I didn’t know you – and I just loved your Joe Mott. Then I looked you up on Wikipedia and it said you were “Canadian-American”.

.

John Douglas Thompson:

Well, I was born in Bath, England, to Jamaican parents, and we moved, when I was a little boy, to Canada. I lived in Montreal from the age of two to 12, then moved to the U.S. So a lot of people say I’m Canadian-American. I’m more Jamaican-American, though I’ve settled on African-American.

.

Did that time in Montreal have an impact on you at all?

.

I have a lot of fond memories of living in Montreal – and the Montreal Canadiens. I was a big, big hockey fan – and my brother and I played a lot of hockey. My mom would always take us to the Stanley Cup parades: Yvan Cournoyer, Ken Dryden.…

.

The Times’s Ben Brantley has called you “one of the most compelling classical stage actors of his generation” – and scholar James Shapiro called you “the best American actor in Shakespeare, hands down.” I was hoping you might say Canada played a role in that.

.

I’ve got to come up to Canada and do some Shakespeare… I’ve had some inquiries from the people at Stratford. The only complication has been my schedule. I hear such great things about that company from Brian Dennehy. And I was in a production of Julius Caesar with Colm Feore (and some guy named Denzel Washington!) on Broadway – and he spoke highly of it too.

.

I thought this Iceman ensemble was extraordinary; I was gripped for the full 4 1/2 hours. Are you glad to have a second chance to play this character in this company?

.

It’s great to get a second opportunity to explore these amazing characters – who all had some kind of relationship with O’Neill. I did a lot of research into Joe Mott – and the real guy was Joe Smith [O’Neill’s roommate and drinking buddy] … I’m always conscious when I’m working on Joe Mott to pay homage to Smith.

.

I read somewhere that O’Neill modeled both Brutus Jones in the 1920s’ The Emperor Jones and Joe Mott on Smith. You’ve played both roles now.

.

The Emperor Jones had the first African-American lead role on the American stage – and I’d venture to say perhaps on the world stage. O’Neill wrote this black character – the protagonist of a play – that was not going to be played by a white man in “blackface”. It was a huge statement. Many of the white actors of the Provincetown Players [MacDougal Street in NYC] wanted to do it because it’s such a great role. And O’Neill said no: It has to be a black actor.

Charles Sidney Gilpin (1878 – 1930), seen in this photograph as Brutus Jones in the 1920 premiere of Eugene ONeill’s The Emperor Jones

.

O’Neill had black characters in his early one-act plays that were maybe one-dimensional or superficial or stereotypical. Then he wrote these major characters – Brutus Jones and Joe Mott. Do you see a progression?

.

Each of these characters from Brutus Jones to Jim Harris [in 1924’s All God’s Chillun Got Wings] to Joe Mott are all advancements on one another. I think someone from the outside looking in, without having done the research, might say these aren’t really strong black characters. If you look further, you find O’Neill had a great deal of respect for these characters that he wrote and was really looking to integrate American theatre. Nobody else was writing black characters at the time, certainly of the size and scope and complexity … Joe Mott to me is like an August Wilson character.

.

It’s still hard to find white playwrights today who will incorporate significant black characters – though now there’s that whole conversation about whether it’s their story to tell.

.

The time that O’Neill did it, it was such a bold move – now, you’re right, we have this argument: Who’s writing this character, who has the “agency” to write these characters? I know in New York, there’s a lot of new, younger black playwrights writing these characters and saying these characters are the terrain of black writers. But I think that any writer with sensitivity, empathy and understanding of humanity can write these characters, certainly as O’Neill has proved.

The Iceman Cometh is at BAM in Brooklyn, N.Y., from Feb. 5th to March 15th, 2015.

. . . . .

William Peyton Hubbard: Toronto’s first Black alderman

Posted: February 2, 2015 Filed under: English | Tags: Black History Month: Toronto Comments Off on William Peyton Hubbard: Toronto’s first Black aldermanZP reprints today an article by Kevin Plummer, a civic historian for “Torontoist” on-line, dating from February 2009:

.

Last year, a local resident discovered that the historical plaque near 660 Broadview Avenue—erected thirty years ago by the Toronto Historical Board to honour William Peyton Hubbard, Toronto’s first Black municipal politician—was damaged. He returned the pieces to Heritage Toronto, who unveiled a replacement marker this week for students at Montcrest School. Over the years, Hubbard has been commemorated in public ceremony, newspaper retrospectives, a biography, and now a second historical plaque.

.

Hubbard’s story offers insight into the ways the lives of prominent citizens can become entangled with the politics of commemoration; and there is a common narrative shared among them all…

William Peyton Hubbard was born in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, in 1842.

The Canadian-born son of a Virginian freed slave, Hubbard worked for sixteen years as a cake baker after graduating from the Toronto Model School. He then became a cab driver. As he was driving one wintry night, he saved another cab from plummeting into the Don River. A friendship blossomed between Hubbard and the grateful occupant of that cab – it was newspaperman George Brown. Brown encouraged him to seek elected office at the age of 51, and though Hubbard was narrowly defeated in the municipal election of 1893, still he had made a strong impression with the public and the press. In 1894, he was elected alderman – his first of fourteen consecutive (and fifteen total) terms in office. Over the course of his career, Hubbard served also on the Board of Control from 1898, and even as acting mayor on more than one occasion.

City of Toronto Archives_photograph from July of 1898_On the roof of Old_then the New_City Hall at Queen and Bay_William Peyton Hubbard is third from right in the bottom row.

Now, in the 21st century, there is always pressure exerted for public commemorations. As Thomas Symons, chair of the Canadian Historic Sites and Monuments Board back in 1997, said: “Heritage is…the aspirations of the people who made it, and, one might add, the aspirations of the people who have chosen to preserve it.” Often this becomes an act that celebrates more than engaging critiques or controversies surrounding historical questions. Looking at a few instances of public commemoration of William Peyton Hubbard—each of which highlights different points of emphasis—we can see how each reveals, or obscures, various aspects of his character; and so we gain a fuller picture of the man.

.

The November 1913 retirement ceremony for William Peyton Hubbard’s life in politics was suitably grandiose. A portrait of Hubbard, painted by W.A. Sherwood, was unveiled. It now hangs in the office of a senior policy advisor – after years on the wall of City Hall’s Committee Room One. With mayors and aldermen past and present in attendance, speeches praised Hubbard’s many political achievements. A conservative, Hubbard brought passion and a keen business sense to public life. As a reformer, he also fought against corruption in government departments, and against the misconduct of government officials.

Although he was quiet and calm in private, Hubbard was a powerful public speaker, whom colleagues dubbed the “Cicero of the Council.” While he attacked anyone verbally – colleagues included – who was guilty of misconduct, Hubbard always did his research to ensure that the evidence supported his accusations. An outspoken nature, and frank honesty—which made for good newspaper copy, too — ensured that Hubbard developed a positive relationship with the press, and this lasted his entire life.

In 1898 he was appointed to the Board of Control, a powerful four-member cabinet that advised the mayor and monitored municipal spending. His pressures for democratic reforms were partly responsible for getting that body elected by citizens at large rather than being appointed by city councillors. For his efforts, Hubbard was re-elected to the Board of Control until 1908 by ever-increasing electoral margins—even topping the polls with 15,035 votes in 1906. He also served on a wide variety of commissions and committees, and assumed leadership roles in the Union of Canadian Municipalities and the Ontario Municipal Association.

.

Hubbard’s long-time stance in favour of municipal ownership of utilities thrust him to the forefront of one of the biggest (and bitterest) debates of the early twentieth century: whether hydro-electric power ought to be developed and operated by private interests or under public control. Working with Adam Beck and the Ontario Hydro-Electric Power Commission, Hubbard eventually secured the legislation necessary to allow Toronto to operate a public electrical grid. Ironically, his tireless efforts towards this cause took him away from his other aldermanic duties, leading to his electoral defeat in 1908. Adam Beck, later knighted for his part in promoting public electric power, even made a surprise appearance at Hubbard’s retirement celebration in 1913—for Hubbard had returned to office in 1913 before retiring to attend to his ailing wife. Beck praised Hubbard as indispensable to the success of the new publicly-owned electric power system.

.

In recalling Hubbard’s achievements in public office up until retirement, newspaper accounts made no mention at all of his race.

This is odd, because readers were certainly well aware of Hubbard’s skin colour, and newspapers hadn’t shied away from it previously. In fact, on occasions when they disagreed with his politics, newspapers sometimes exaggerated his racial features. On other occasions, the press pointed to Hubbard’s success as evidence that racial prejudice was not a problem in forward-thinking Toronto. In 1913, journalistic blindness to this context downplaying why Hubbard achieving what he did when he did is all the more remarkable.

.

Although genuine concern for Toronto’s Black community existed in in the city, that sentiment could also be paternalistic. As York University’s Dr. Wilson Head has said: Blacks “were seen as people who belonged here, but not to be gotten too close to.” In Hubbard’s time, Toronto’s pioneer Black population hardly constituted an economic or political force. The population of this community—concentrated in Ward Three—was tiny, and had little to offer to potential political allies as a voting bloc, according to Keith S. Henry in Black Politics in Toronto Since World War I (published in 1981). On the other hand, a sparse population meant that this community was not seen as threatening to the dominant social order. Hubbard was therefore deftly able to chart his own individual course through the social politics of the day, buoyed by his father’s philosophy of Self-Improvement. He cultivated connections to the social establishment during his youth at the highly respected Toronto Model School, and through his life-long attendance at St. George’s Anglican Church on John Street. And so, for most of his career, Hubbard represented Ward Four—not Ward Three as one might expect—which was inhabited by an affluent (and almost exclusively white) population of professionals and intellectuals. Reports of his 1913 retirement therefore obscure Hubbard’s agility in surmounting the inequities of the age faced by the larger Black community.

.

By the time Hubbard was commemorated with a historical plaque in 1979, a number of newspaper articles had re-interpreted his story through the prism of Multiculturalism. The plaque’s text re-assessed him as “a champion of the rights of various minorities.” Lorraine Hubbard, then-VP of the Ontario Black History Society, argued that as “somebody who was quite visible from the norm,” Hubbard “got involved in issues that no-one else had touched before, issues that no-one else would go near because they were afraid that these were unpopular at the time.” Hubbard’s forty-year involvement with the House of Industry charity certainly attests to his social conscience, but there are only a handful of occasions on record when he actively pressed for minority rights in the council chambers. In placing such emphasis on this aspect of Hubbard’s life, the 1979 plaque and Against All Odds (1986)—the biography written by Stephen L. Hubbard, his great-great-grandson—do not place Hubbard into the broader critical context of Black politics in Toronto.

.

In a review of Hubbard’s biography for the Canadian Historical Review in December 1988, historian James W. St. G. Walker notes that Hubbard “saw himself as an able and respected municipal politician, not as a representative of, or an example to, the Black community.” Despite being a member of Black community organizations such as the Home Service Association and the Musical and Literary Society of Toronto, Hubbard rarely spoke about race, even in private correspondence.

Walker continues: “Hubbard himself never confronted the intriguing contradiction between his personal acceptance and the limitations imposed on most Canadian Blacks.” In a rare instance of such reflection, he noted to his close friend, (and the first Canadian-born Black doctor), Dr. Anderson Ruffin Abbott (1837-1913): “I have always felt that I am a representative of a race hitherto despised, but, given fair opportunity, would be able to command esteem.”

Author Henry recounts in detail how the demographics of Toronto’s Black community changed substantially after the First World War, with a large influx of immigrants from the British West Indies, plus migrant workers from the United States. Even the most skilled and educated of this growing population found themselves locked out of professional careers. With a different experience and political perspective, the newer arrivals, according to Henry, were critical of the traditional, native-born Old Line families. Hubbard and Abbott, it was thought, were too conservative. Writing in A History of Blacks in Canada (1981), Walker adds that even when Hubbard was serving as acting mayor, Toronto Blacks were barred from many restaurants and hotels.

.

These critical perspectives take not an ounce away from Hubbard’s many achievements.

But, given how outspoken he was about countless other political issues, his silence on matters of race is all the more deafening. It adds texture to his character, and to our historical understanding of him. Hubbard’s case also illustrates how public commemorations – especially those erected to mark a “first” pioneer who did not always act as we imagine he should have acted – can place our own present-day burdens on those who defined themselves according to their own personal principles, convictions, and foibles. As celebrations of our past, plaques—like the one unveiled this week near the grand house at 660 Broadview where Hubbard resided until his death on April 13, 1935—play an essential role. They connect us to the past by illuminating the characters or events our streets, parks, and community centres are named for. But since they are not intended to give the whole story, they can act only as a jumping off point, enticing us to explore further, and to try to fill in the blank spaces, contradictions, and controversies of our city’s history.

. . . . .

Nicomedes Santa Cruz: “Congo”

Posted: February 1, 2015 Filed under: Nicomedes Santa Cruz, Spanish | Tags: El Mes de la Historia Afroamericana Comments Off on Nicomedes Santa Cruz: “Congo”Nicomedes Santa Cruz (1925-1992, poeta afroperuano)

Congo (para Patrice Lumumba)

.

Mi madre parió un negrito

al divorciarse de su hombre,

es congo, congo, conguito,

Y Congo tiene por nombre.

.

Todos piden que camine

y lo parieron ayer.

Otros, que se elimine

sin acabar de nacer…

.

¡Ay Congo,

Yo sí me opongo!

.

El mundo te mira absorto

por tu nacimiento obscuro.

Te consideran aborto

por tu gatear inseguro.

.

¡Ay Congo,

Cuánto rezongo!

.

Yo he visto blancos nacer

en condiciones iguales,

y sus tropiezos de ayer

se consideran normales.

.

Mi Congo, congolesito

que Congo tiene por nombre,

hoy día es sólo un negrito

mañana será un gran hombre:

A las Montañas Mitumba

llegará su altiva frente,

Y el caudaloso Luaba

Tendrá en sanguíneo torrente.

.

¡Sí Congo,

Y no supongo!

.

África ha sido la madre

que pariera en un camastro

Al niño Congo, sin padre,

Que no desea padastro.

.

¡África, tierra sin frío,

madre de mi obscuridad;

cada amanecer ansío,

cada amanecer ansío,

cada amanecer ansío

tu completa libertad!

. . . . .

Other poems by Nicomedes Santa Cruz / Otros poemas por Nicomedes Santa Cruz: https://zocalopoets.com/2012/02/12/nicomedes-santa-cruz-black-rhythms-of-peru-ritmos-negros-del-peru/

.

Bruce Patrick Jones: Silueta de La Mujer como El Árbol con Raíces

Donald Willard Moore and the Negro Citizenship Association: Changing Canada’s immigration policy for the better

Posted: February 1, 2015 Filed under: English | Tags: Black History Month in Canada Comments Off on Donald Willard Moore and the Negro Citizenship Association: Changing Canada’s immigration policy for the better

Railway clips from the Grand Trunk Railroad / Canadian National Railroad line between Quebec and Ontario, the tracks that brought Donald Willard Moore from Montreal to Toronto…

Donald Willard Moore and the Negro Citizenship Association

. . .

Excerpt from the Negro Citizenship Association’s 1954 brief to Canada’s Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration:

The Immigration Act since 1923 seems to have been purposely written and revised to deny equal immigration status to those areas of the Commonwealth where coloured peoples constitute a large part of the population. This is done by creating a rigid definition of British Subject: ‘British subjects by birth or by naturalization in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand or the Union of South Africa and citizens of Ireland.’ This definition excludes from the category of ‘British subject’ those who are in all other senses British subjects, but who come from such areas as the British West Indies, Bermuda, British Guiana, Ceylon, India, Pakistan, Africa, etc…Our delegation claims this definition of British subject is discriminatory and dangerous.

.

Donald Willard Moore (1891-1994) was a community leader and civil-rights activist who fought to change Canada’s exclusionary immigration laws.

Moore was born at Lodge Hill in St. Michael’s Parish, Barbados, in November of 1891. His parents were Charles Alexander Moore, a cabinetmaker and member of the Barbados Harbour Police Force, and Ruth Elizabeth Moore.

.

At the age of 21, Moore left his family and emigrated to the U.S.A., but soon left New York City for Montreal. He found work with the Canadian Pacific Railway as a sleeping car porter and his job brought him to Toronto. Moore earned enough to enrol in The Dominion Business College at 357 College Street, where he completed the courses necessary to allow him to register in the dentistry programme at Dalhousie University in Halifax in 1918.

.

A lengthy bout of tuberculosis brought an end to Moore’s formal education and his hopes of becoming a dentist. In need of money, he took a job as a tailor, a trade he had learned in Barbados. In 1920, Moore began working at Occidental Cleaners and Dyers, located at 318 Spadina Avenue between St. Patrick Street (now Dundas Street West) and St. Andrew Street. Eventually he was able to purchase the business.

Moore’s store was a gathering place for the West Indian community. It was there that the Toronto branch of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association was established, as well as the West Indian and Progressive Association and the West Indian Trading Association. Moore would continue to operate his business in various locations until his retirement in 1975.

.

In 1951, Moore founded what came to be known as the Negro Citizenship Association, a social and humanitarian organization with the motto “Dedicated to the promotion of a better Canadian citizen.” The association’s aim was to challenge the systematic denial of black West Indians seeking legal entry into Canada, and to bring an end to the incarceration of individuals who were awaiting either deportation or decisions on deportation order appeals.

.

In April of 1954 Moore led a delegation to Ottawa, which included 34 representatives from the Negro Citizenship Association as well as unions, labour councils, and community organizations. They presented a brief to Canada’s Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, Walter E. Harris.

The brief drew public attention to Canada’s discriminatory immigration laws, which were denying equal immigration status to non-white British subjects, described the impact of those laws, and made specific recommendations for change.

1954 photograph of Negro Citizenship Association Reception Tea_Donald Moore is in the back row third in from the right.