Poem for Beginning Anew: “Zamzam” by Doyali Farah Islam

Posted: November 4, 2013 Filed under: Doyali Farah Islam, English | Tags: Muharram, New Year Comments Off on Poem for Beginning Anew: “Zamzam” by Doyali Farah IslamDoyali Farah Islam

“Zamzam”

.

Zamzam was found

under a heap of dung,

where the blood of rites

fertilized stone.

.

… Zamzam … was found …

under a heap of dung.

.

it was ‘Abd al-Muttalib

who decided which to cherish.

.

it wasn’t just springwater,

but his decision

that was the freshness.

.

… this ground we unmuck

called listening heart

carves deep the shallowest

cup.

.

somewhere breathes its breath

from between your two breasts.

.

(no need to divine

perfect locations;

approximations are enough.)

.

… out in the plain open, I was searching for a particular thing,

and a thousand hidden

wellsprings of treasure

passed me by.

.

Hajar runs between two hills, desperate to find what quenches thirst.

.

then she gives up going back and forth in the desert of fear,

and Ishmael’s heel strikes water.

. . .

Poet’s notes on “Zamzam”:

Zamzam:

The Well of Zamzam was in use from the time of Ishmael and Hajar’s story (explained below), until it was filled with the treasures of pilgrimage offerings by the Jurhumites who controlled Mecca (Lings 4). The Jurhumites covered the well with sand, and the water source was largely forgotten (Lings 5). Many years later, ‘Abd al-Muttalib, sleeping near the Ka‘bah, heard the Divine command, “Dig Zamzam!” (Lings 10). The well was recovered, and it still serves Muslim pilgrims on Hajj.

‘Abd al-Muttalib:

While the “heap” element in the poem is hyperbolic, Muhammad’s grandfather, ‘Abd al-Muttalib, did re-locate the spring of Zamzam near the Ka‘bah at the site upon which he found dung, an ant’s nest, as well as blood from ritual sacrifices performed by the Quraysh (Lings 10-11).

Hajar and Ishmael:

Hajar (Biblical: Hagar), the second wife of Abraham, after Sarah, was alone in the desert with her baby, Ishmael. Desperate to find water, she ran between two hillocks – now called Safā and Marwah – so that she could view the desert from better vantage points. After seven tries with no sight of a caravan, she gave up and sat down. A well sprang up where Ishmael’s heel touched the ground (Lings 2-3). This well became the Well of Zamzam.

.

Reference: Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources by Martin Lings (Inner Traditions/Bear & Co.) © 1983, 1991, 2006, originally published in the UK by George Allen & Unwin © 1983.

. . .

“Zamzam” is taken from Doyali Farah Islam’s 2011 collection, Yūsuf and the Lotus Flower, published by Buschek Books in Ottawa, Canada.

Doyali Farah Islam is the first-place winner of Contemporary Verse 2’s 35th Anniversary Contest, and her poems have appeared in Grain Magazine (38.2), amongst other places. Born to Bangladeshi parents, Islam grew up in Toronto and spent four years abroad in London, England. As to her true dwelling place, she can only offer: “I am borrowed breath. / if you too are borrowed, / we meet in the home of our breather.” Islam holds a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature and Equity Studies from the University of Toronto (Victoria College).

.

Image: Water – a photograph by Laboni Islam

. . . . .

All Souls Day and Dorothy Parker: “You might as well live.”

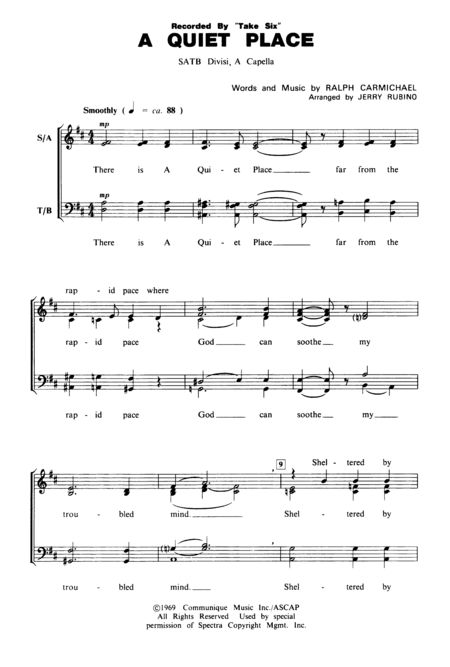

Posted: November 2, 2013 Filed under: Dorothy Parker, English Comments Off on All Souls Day and Dorothy Parker: “You might as well live.” ZP_Frontispiece for Dorothy Parker’s Enough Rope_1926_taken from her 1936 collected poems entitled Not so deep as a well

ZP_Frontispiece for Dorothy Parker’s Enough Rope_1926_taken from her 1936 collected poems entitled Not so deep as a well

.

In 1914, 21-year-old Dorothy Parker was hired by Vogue magazine in New York as an editorial assistant. By 1918 she was a staff writer for Vanity Fair where she began penning play reviews in place of an on-holiday P.G. Wodehouse.

The way she wrote – how to describe it? This was something new: cute as a button, sharp as a tack; the driest gin with a drop of grenadine syrup. After two years the editor fired her for offending a bigwig producer (Broadway impresario Flo Ziegfeld), but she had already made a name for herself as a “fast woman” – fast with words, that is. Throughout the 1920s she would contribute several hundred poems and numerous columns to Life, McCall’s, Vogue, The New Republic, and The New Yorker (where she was one of that magazine’s earliest contributors when it began publishing in 1925.) Whatever her snappy, clever, seemingly off-the-cuff social commentaries projected – whether in theatre / book reviews or luncheon quips as a “member” of The Algonquin Round Table – Dorothy Parker’s poetry dealt much in love’s loss or love’s rejection; melancholy and sorrow; the appealing thought of one’s own Death.

ZP_a young Dorothy Parker_around 1918

ZP_a young Dorothy Parker_around 1918

Parker is a poet who’s just right to feature on All Souls Day. Indeed, she made the magnetic appeal of Death plain in her book titles: Death and Taxes, Laments for the Living, and Here Lies. We celebrate her peculiarly morbid liveliness with words, a liveliness she displayed even when she was really really down and joked – seriously – as only she could – about suicide. Quoted in Vanity Fair in 1925, Parker proposed that her epitaph be: “Excuse my dust.” Mistress of self-deprecation or being on the attack; vulnerable and wistful or hard as nails; Parker was such things. This made her – still makes her today – a complex ‘read’. But she’s worth it.

.

Born in 1893 to a German-Jewish father and a mother of Scottish descent who died when Dorothy was four years old, Parker (her married name from her first husband, a Wall-Street stockbroker, in 1917) – referred to her stepmother, whom her father married in 1900, as “the housekeeper” – early evidence of that wise-crack wit. Her father died in 1913, and by then Parker was already earning a living playing piano at a dance studio…and beginning to work on her verse.

.

Parker in the next two decades wrote a handful of incisive, bittersweet short stories – “Big Blonde” won the 1929 O. Henry Award – and her literary reputation rests on those pieces as much as on her poetry. In 1928 she divorced from her first husband then had a series of affairs, one of which resulted in an abortion and a suicide attempt (among several over the years). Of that amour and pregnancy she remarked: “How like me to put all my eggs into one bastard.”

.

But even by the time she reached middle age she remained insecure about her literary abilities. And upon her death in 1967 – of a heart attack, not suicide – she was living in an apartment-hotel in Manhattan and was – in truth – “forgotten but not gone.” In a 1956 interview in The Paris Review she stated: “There’s a hell of a distance between wise-cracking and wit. Wit has truth in it; wise-cracking is simply calisthenics with words.” For this was one of her gnawing worries: was she just a wise-cracker and not a true wit? In fact, she was both – and in the New York of the 1920s – at least until the Wall Street “crash” of 1929 – there was room for the two; the wise-cracker got more press, though. One of her best poems combines both wise-crack and wit, in the right balance – perhaps something only she could do.

“Résumé”

.

Razors pain you;

Rivers are damp;

Acids stain you;

And drugs cause cramp.

Guns aren’t lawful;

Nooses give;

Gas smells awful;

You might as well live.

. . .

“Résumé” is from Parker’s first volume of poetry entitled Enough Rope (published 1926). The following poems are also taken from that collection:

.

“The Small Hours”

.

No more my little song comes back;

And now of nights I lay

My head on down, to watch the black

And wait the unfailing grey.

.

Oh, sad are winter nights, and slow;

And sad’s a song that’s dumb;

And sad it is to lie and know

Another dawn will come.

. . .

“The Trifler”

.

Death’s the lover that I’d be taking;

Wild and fickle and fierce is he.

Small’s his care if my heart be breaking –

Gay young Death would have none of me.

.

Hear them clack of my haste to greet him!

No one other my mouth had kissed.

I had dressed me in silk to meet him –

False young Death would not hold the tryst.

.

Slow’s the blood that was quick and stormy,

Smooth and cold is the bridal bed;

I must wait till he whistles for me –

Proud young Death would not turn his head.

.

I must wait till my breast is wilted,

I must wait till my back is bowed,

I must rock in the corner, jilted –

Death went galloping down the road.

.

Gone’s my heart with a trifling rover.

Fine he was in the game he played –

Kissed, and promised, and threw me over,

And rode away with a prettier maid.

. . .

“A very short Song”

.

Once, when I was young and true,

Someone left me sad –

Broke my brittle heart in two;

And that is very bad.

.

Love is for unlucky folk,

Love is but a curse.

Once there was a heart I broke;

And that, I think, is worse.

. . .

“Light of Love”

.

Joy stayed with me a night –

Young and free and fair –

And in the morning light

He left me there.

.

Then Sorrow came to stay,

And lay upon my breast;

He walked with me in the day,

And knew me best.

.

I’ll never be a bride,

Nor yet celibate,

So I’m living now with Pride –

A cold bedmate.

.

He must not hear nor see,

Nor could he forgive

That Sorrow still visits me

Each day I live.

. . .

“Somebody’s Song”

.

This is what I vow:

He shall have my heart to keep;

Sweetly will we stir and sleep,

All the years, as now.

Swift the measured sands may run;

Love like this is never done;

He and I are wedded one:

This is what I vow.

.

This is what I pray:

Keep him by me tenderly;

Keep him sweet in pride of me,

Ever and a day;

Keep me from the old distress;

Let me, for our happiness,

Be the one to love the less:

This is what I pray.

.

This is what I know:

Lovers’ oaths are thin as rain;

Love’s a harbinger of pain –

Would it were not so!

Ever is my heart a-thirst,

Ever is my love accurst;

He is neither last nor first:

This is what I know.

. . .

“The New Love”

.

If it shine or if it rain,

Little will I care or know.

Days, like drops upon a pane,

Slip and join and go.

.

At my door’s another lad;

Here’s his flower in my hair.

If he see me pale and sad,

Will he see me fair?

.

I sit looking at the floor.

Little will I think or say

If he seek another door;

Even if he stay.

. . .

“I shall come back”

.

I shall come back without fanfaronade

Of wailing wind and graveyard panoply;

But, trembling, slip from cool Eternity –

A mild and most bewildered little shade.

I shall not make sepulchral midnight raid,

But softly come where I had longed to be

In April twilight’s unsung melody,

And I, not you, shall be the one afraid.

.

Strange, that from lovely dreamings of the dead

I shall come back to you, who hurt me most.

You may not feel my hand upon your head,

I’ll be so new and inexpert a ghost.

Perhaps you will not know that I am near –

And that will break my ghostly heart, my dear.

. . .

“Chant for Dark Hours”

.

Some men, some men

Cannot pass a

Book shop.

(Lady, make your mind up, and wait your life away.)

.

Some men, some men

Cannot pass a

Crap game.

(He said he’d come at moonrise, and here’s another day!)

.

Some men, some men

Cannot pass a

Woman.

(Wait about, and hang about, and that’s the way it goes.)

.

Some men, some men

Cannot pass a

Golf course.

(Read a book, and sew a seam, and slumber if you can.)

.

Some men, some men

Cannot pass a

Haberdasher’s.

(All your life you wait around for some damn man!)

. . .

“Unfortunate Coincidence”

.

By the time you swear you’re his,

Shivering and sighing,

And he vows his passion is

Infinite, undying –

Lady, make note of this:

One of you is lying.

. . .

“Inventory”

.

Four be the things I am wiser to know:

Idleness, sorrow, a friend, and a foe.

.

Four be the things I’d been better without:

Love, curiosity, freckles, and doubt.

.

Three be the things I shall never attain:

Envy, content, and sufficient champagne.

.

Three be the things I shall have till I die:

Laughter and hope and a sock in the eye.

. . .

“Philosophy”

.

If I should labour through daylight and dark,

Consecrate, valorous, serious, true,

Then on the world I may blazon my mark;

And what if I don’t, and what if I do?

. . .

“Men”

.

They hail you as their morning star

Because you are the way you are.

If you return the sentiment,

They’ll try to make you different;

And once they have you, safe and sound,

They want to change you all around.

Your moods and ways they put a curse on;

They’d make of you another person.

They cannot let you go your gait;

They influence and educate.

They’d alter all that they admired.

They make me sick, they make me tired.

. . .

“General Review of the Sex Situation”

.

Woman wants monogamy;

Man delights in novelty.

Love is woman’s moon and sun;

Man has other forms of fun.

Woman lives but in her lord;

Count to ten, and man is bored.

With this the gist and sum of it,

What earthly good can come of it?

. . .

The following poems are taken from Parker’s volume Death and Taxes (published 1931):

.

“Requiescat”

.

Tonight my love is sleeping cold

Where none may see and none shall pass.

The daisies quicken in the mold,

And richer fares the meadow grass.

.

The warding cypress pleads the skies,

The mound goes level in the rain.

My love all cold and silent lies –

Pray God it will not rise again!

. . .

“The Lady’s Reward”

.

Lady, lady, never start

Conversation toward your heart;

Keep your pretty words serene;

Never murmur what you mean.

Show yourself, by word and look,

Swift and shallow as a brook.

Be as cool and quick to go

As a drop of April snow;

Be as delicate and gay

As a cherry flower in May.

Lady, lady, never speak

Of the tears that burn your cheek –

She will never win him, whose

Words had shown she feared to lose.

Be you wise and never sad,

You will get your lovely lad.

Never serious be, nor true,

And your wish will come to you –

And if that makes you happy, kid,

You’ll be the first it ever did.

. . .

“Coda” (from Parker’s 1928 volume Sunset Gun)

.

There’s little in taking or giving,

There’s little in water or wine;

This living, this living, this living

Was never a project of mine.

Oh, hard is the struggle, and sparse is

The gain of the one at the top,

For art is a form of catharsis,

And love is a permanent flop,

And work is the province of cattle,

And rest’s for a clam in a shell,

So I’m thinking of throwing the battle –

Would you kindly direct me to Hell?

. . . . .

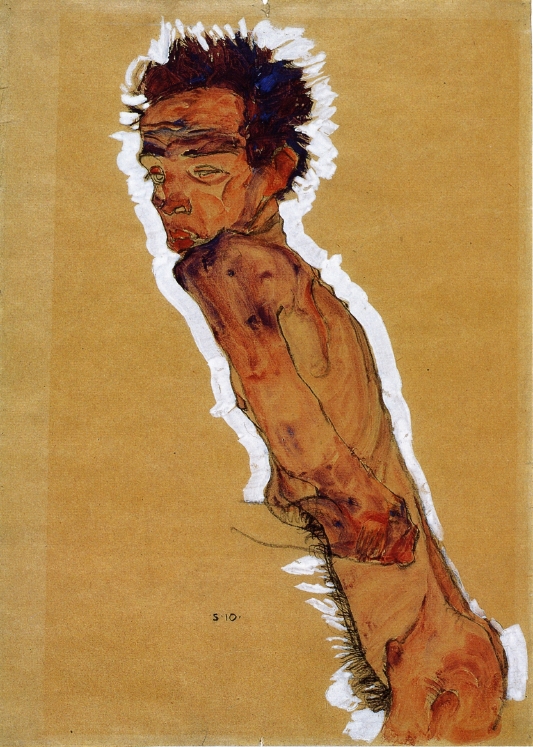

Egon Schiele: Ich bin Mensch, ich liebe / Den Tod und Liebe / Das Leben. “I am a Human Being – I love Death and Love – They are alive.”

Posted: October 31, 2013 Filed under: A FEW FAVOURITES / UNA MUESTRA DE FAVORITOS, Egon Schiele, English, German | Tags: German Expressionist poets Comments Off on Egon Schiele: Ich bin Mensch, ich liebe / Den Tod und Liebe / Das Leben. “I am a Human Being – I love Death and Love – They are alive.” ZP_Egon Schiele_Selfportrait_Male nude in profile, facing left_1910

ZP_Egon Schiele_Selfportrait_Male nude in profile, facing left_1910

.

Strange Austrian “wunderkind” Egon Schiele was the son of a railroad station-master in Tulln and a mother from Krumau in Bohemia (Czechoslovakia). Schiele began to draw at the age of 18 months, and was disturbingly precocious when it came to early explorations of his own sexuality. Schiele’s paintings and drawings are always – unmistakably – his, and the artist died on this day (October 31st) in 1918, at the age of 28. One of the many millions who succumbed to the ineptly-named “Spanish Flu” pandemic which began in January 1918 – before the end of what was then known as The Great War – and lasted until December 1920 – Schiele’s art had had, even before the War, so much of Death about it – and yet also of Eros, and of Love. One of the artist’s own poems – and he did write a handful of them to accompany several canvases – states simply: Ich bin Mensch, ich liebe / Den Tod und Liebe / Das Leben. “I am a human being – I love Death and Love – they are alive.” Schiele’s wife Edith, six months pregnant, died of the “Spanish Flu” on October 28th, 1918, and Schiele, himself already extremely ill, made several sketches of her as she lay dying. He was gone just three days later.

.

Translators Will Stone and Anthony Vivis wrote, in an issue of The London Magazine: “In one of his untitled poems Schiele talks of a bird where ‘a thousand greens are reflected in its eyes’. That this was written by an artist of Schiele’s calibre infuses the image with added significance. Who but he could know the shade created by a thousand greens and hold it long enough to record? What matters is not literally that a thousand greens reflect in the bird’s eye, but the possibility that they could. The green of the eye is so overwhelming that in his determination to see truth above all else the precocious poet-artist has glutted himself with a thousand variations within a single colour. While admitting the impossibility of capturing the reality of nature – like a translator faced with a text which appears to defy intra-linguistic interpretation – Schiele takes up the challenge nevertheless. It is a microcosm of the artistic calling: proceeding with creation and conceding defeat at the same moment. The sense of precariousness, the constant wavering of the boundary between lucidity and excruciation, is perhaps why Schiele’s paintings score so deeply into us even today [April 2012].”

.

The Viennese, bourgeois-art-appreciating public had found Schiele’s un-pretty style and colour palette – often there were grey-green hues for skin, as if the living were putrefying – and his candid, awkward-limbed sexuality / unflattering poses / the angst *of his nudes – difficult to look upon. Yet he was really a proto–Expressionist who was leading the way for Expressionism** – that most powerful German artistic movement of the first quarter of the 20th century. Schiele’s influences were Vincent Van Gogh, “Art-Nouveau”, and Gustav Klimt – all from his boyhood – but it’s the poets, not visual artists, of the decade from 1910 forward, that explored – like Schiele was doing – similar discomfiting emotional and psychological “territories”. And so, we have placed a selection of their verses alongside poems of and images of paintings and drawings by Egon Schiele.

.

* Angst is a great-sounding word. It reached German – and English – via the Danish language and an 1844 treatise by the philosopher Kierkegaard. Angst means Existential anxiety or fear.

** German Expressionism – a definition from Ruth J. Owen:

“A Modernist mode, mainly in the second decade of the 20th century; perspective of angst and absurdity; disturbing visions of downfall and decay; pathological world of the crippled and insane, and images of the city and war. ‘Aufbruch’ (an awakening or departure from) becomes ubiquitous – a new era; dislocated colour, shrill tone; the grotesque, deathliness and dissolution.”

. . .

Egon Schiele (1890-1918)

“Ein Selbstbild” / “Self-Portrait” (1910)

.

Ich bin für mich und die, denen

Die durstige Trunksucht nach

Freisein bei mir alles schenkt,

und auch für alle, weil alle

ich auch Liebe, – Liebe

.

Ich bin von vornehmsten

Der Vornehmste

Und von Rückgebern

Der Rückgebigste

.

Ich bin Mensch, ich liebe

Den Tod und Liebe

Das Leben.

. . .

Egon Schiele

“Sensation”

.

High vast winds turned my spine to ice

and I was forced to squint.

On a scratchy wall I saw

the entire world

with all its valleys, mountains and lakes,

with all the animals running around

shadows of trees and the patches of sun

reminded me of clouds.

I strode upon the earth

and had no sense of my limbs

I felt so light.

. . .

“Empfindung”

.

Hohe Grosswinde machten kalt mein Rückgrat

und da schielte ich.

Auf einer krätzigen Mauer sah ich

die ganze Welt

mit allen Tälern und Bergen und Seen,

mit all den Tieren, die da umliefen –

Die Schatten der Bäume und die Sonnenflecken erinnerten

mich an die Wolken.

Auf der Erde schritt ich

und spürte meine Glieder nicht,

so leicht war mir.

. . .

Egon Schiele

“Music while drowning”

.

In no time the black river yoked all my strength

I saw the lesser waters great

and the soft banks steep and high.

.

Twisting I fought

and heard the waters within me,

the fine, beautiful black waters –

then I breathed golden strength once more.

The river ran rigid and more strongly.

. . .

“Musik beim ertrinken”

.

In Momenten jochte der schwarze Fluss meine ganzen Kräfte.

Ich sah die kleinen Wasser gross

Und die sanften Ufer steil und hoch.

.

Drehend rang ich

und hörte die Wasser in mir,

die guten, schönen Shwarzwasser –

Dann atmete ich wieder goldene Kraft.

Der Strom strömte starr und stärker.

.

Egon Schiele’s poems: translations from the German © Will Stone and Anthony Vivis

. . .

Else Lasker-Schüler (1869-1945)

“Oh, let me leave this world”

.

Then you will cry for me.

Copper beeches pour fire

On my warlike dreams.

Through dark underbrush

I crawl,

Through ditches and water.

Wild breakers beat

My heart incessantly;

The enemy within.

Oh let me leave this world!

But even from far away

I’d wander – a flickering light –

Around God’s grave.

. . .

“O ich möcht aus der Welt”

.

Dann weinst du um mich.

Blutbuchen schüren

Meine Träume kriegerisch.

Durch finster Gestrüpp

Muß ich

Und Gräben und Wasser.

Immer schlägt wilde Welle

An mein Herz;

Innerer Feind.

O ich möchte aus der Welt!

Aber auch fern von ihr

Irr ich, ein Flackerlicht

Um Gottes Grab.

. . .

. . .

|

Gottfried Benn (1886-1956) D-Zug Braun wie Kognak. Braun wie Laub. Rotbraun. Malaiengelb. |

Gottfried Benn Express Train Brown as cognac. Brown as leaves. Red-brown. Malayan yellow. . (1912) Translation from the German © Michael Hamburger |

|

Gottfried Benn Vor Einem Kornfeld Vor einem Kornfeld sagte einer: |

Gottfried Benn Before a Cornfield Before a cornfield he said: . (1913) Translation from the German © SuperVert |

.

Georg Heym (1887-1912)

“Umbra vitae”

.

Die Menschen stehen vorwärts in den Straßen

Und sehen auf die großen Himmelszeichen,

Wo die Kometen mit den Feuernasen

Um die gezackten Türme drohend schleichen.

Und alle Dächer sind voll Sternedeuter,

Die in den Himmel stecken große Röhren.

Und Zaubrer, wachsend aus den Bodenlöchern,

In Dunkel schräg, die einen Stern beschwören.

Krankheit und Mißwachs durch die Tore kriechen

In schwarzen Tüchern. Und die Betten tragen

Das Wälzen und das Jammern vieler Siechen,

und welche rennen mit den Totenschragen.

Selbstmörder gehen nachts in großen Horden,

Die suchen vor sich ihr verlornes Wesen,

Gebückt in Süd und West, und Ost und Norden,

Den Staub zerfegend mit den Armen-Besen.

Sie sind wie Staub, der hält noch eine Weile,

Die Haare fallen schon auf ihren Wegen,

Sie springen, daß sie sterben, nun in Eile,

Und sind mit totem Haupt im Feld gelegen.

Noch manchmal zappelnd. Und der Felder Tiere

Stehn um sie blind, und stoßen mit dem Horne

In ihren Bauch. Sie strecken alle viere

Begraben unter Salbei und dem Dorne.

Das Jahr ist tot und leer von seinen Winden,

Das wie ein Mantel hängt voll Wassertriefen,

Und ewig Wetter, die sich klagend winden

Aus Tiefen wolkig wieder zu den Tiefen.

Die Meere aber stocken. In den Wogen

Die Schiffe hängen modernd und verdrossen,

Zerstreut, und keine Strömung wird gezogen

Und aller Himmel Höfe sind verschlossen.

Die Bäume wechseln nicht die Zeiten

Und bleiben ewig tot in ihrem Ende

Und über die verfallnen Wege spreiten

Sie hölzern ihre langen Finger-Hände.

Wer stirbt, der setzt sich auf, sich zu erheben,

Und eben hat er noch ein Wort gesprochen.

Auf einmal ist er fort. Wo ist sein Leben?

Und seine Augen sind wie Glas zerbrochen.

Schatten sind viele. Trübe und verborgen.

Und Träume, die an stummen Türen schleifen,

Und der erwacht, bedrückt von andern Morgen,

Muß schweren Schlaf von grauen Lidern streifen.

. . .

Georg Heym

“Umbra vitae” (The Shadow of Life)

.

The people stand forward in the streets

They stare at the great signs in the heavens

Where comets with their fiery trails

Creep threateningly about the serrated towers.

And all the roofs are filled with stargazers

Sticking their great tubes into the skies

And magicians springing up from the earthworks

Tilting in the darkness, conjuring the one star.

Sickness and perversion creep through the gates

In black gowns. And the beds bear

The tossing and the moans of much wasting

They run with the buckling of death.

The suicides go in great nocturnal hordes

They search before themselves for their lost essence

Bent over in the South and West and the East and North

They dust using their arms as brooms.

They are like dust, holding out for a while

The hair falling out as they move on their way,

They leap, conscious of death, now in haste,

And are buried head-first in the field.

Yet occasionally they twitch still. The animals of the field

Blindly stand around them, poking with their horn

In the stomach. They lie on all fours

Buried under sage and thorn.

The year is dead and emptied of its winds

That hang like a coat covered with drops of water

And eternal weather, which bemoaning turns

From cloudy depth again to the depths.

But the seas stagnate. The ships hang

Rotting and querulous in the waves,

Scattered, no current draws them

And the courts of all heavens are sealed.

The trees fail in their seasonal change

Locked in their deadly finality

And over the decaying path they spread

Their wooden long-fingered hands.

He who dies undertakes to rise again,

Indeed he just spoke a word.

And suddenly he is gone. Where is his life?

And his eyes are like shattered glass.

Many are shadows. Grim and hidden.

And dreams which slip by mute doors,

And who awaken, depressed by other mornings,

Must wipe heavy sleep from greyed lids.

.

(1912)

.

Heym translation © Scott Horton

. . . . .

ZP_Egon Schiele_photographed at the age of 24 by Anton Josef Trcka_1914

ZP_Egon Schiele_photographed at the age of 24 by Anton Josef Trcka_1914

.

Images (paintings and drawings) featured here:

Egon Schiele_Selfportrait_Male nude in profile, facing left_1910

Egon Schiele_Selfportrait with arm twisted above head_1910

Egon Schiele_Reclining male nude_1911

Egon Schiele_Composition with three male figures_Selfportrait_1911

Egon Schiele_Male nude with a red loincloth_1914

Egon Schiele_Sitzender weiblicher Akt_Female nude sitting_1914

Egon Schiele_Death and the Maiden_1915

Egon Schiele_Sitzende frau mit hochgezogenem knie_The model was – possibly – Wally Neuzil (1894 – 1917). Neuzil was a former model for Gustav Klimt and she became Schiele’s model / muse / lover before his marriage to Edith Harms.

Egon Schiele_Reclining woman with green stockings_Adele Harms_1917

Egon Schiele_Embrace_Lovers II_1917

Egon Schiele_Edith sterbend_Edith dying_October 28th 1918_the last drawing by Schiele

. . . . .

Alicia Claudia González Maveroff: “Verdun”

Posted: October 21, 2013 Filed under: Alicia Claudia González Maveroff, English, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Alicia Claudia González Maveroff: “Verdun”Alicia Claudia González Maveroff

“Verdun”

.

And now that I’m going, now that I depart,

now that autumn will be my spring;

yes, now that I’m going, I know that for always

I will carry within me

this river, and this autumn red

in the pupil of my eye.

Well, now that I go, knowing that

tomorrow I journey through another river,

perhaps seeking that “bonanza” of calm

that rivers just don’t have because

they “walk fast – and keep moving…”;

in my soul the memory remains –

of the river, road, bridge;

those autumn colours – red, yellow –

painted among the trees.

I had already loved before, long before,

many landscapes, blue skies, other trees…

But – here today –

I loved this river, this bridge and this road;

these trees – red and yellow –

painted by autumn.

.

(Toronto, Canada, 21-10-2011)

. . .

“Verdun”

.

Y ahora que me voy, ahora que parto,

ahora que el otoño será mi primavera,

ahora que me voy, sé que por siempre,

seguro llevaré este río en mi memoria

y el rojo del otoño en mis pupilas.

Bien, ahora que me voy, sabiendo

que caminaré mañana en otro río,

tal vez lo haga buscando yo “la calma”

que el agua de los ríos no la tiene,

porque “caminan fuerte y siempre pasan”.

Más quedan en mi alma, los recuerdos,

el río, el camino, el puente

el rojo y amarillo del otoño,

pintado entre los árboles.

Yo ya había amado antes:

amé muchos paisajes, hace tiempo,

amé cielos celestes y otros árboles…

Pero hoy aquí, yo amé:

este rió, este puente, este camino

y estos árboles de rojo y amarillo

pintados en otoño…

.

(Toronto, Canadá, 21-10-2011)

. . .

Preguntamos al poeta: Que es el significado del título del poema?

Y ella nos dijo:

Te comento que el poema se llama “Verdun” por el barrio de Montréal, Québec. Allí viví cuando visité Canadá y me enamoré de este país. El poema lo escribí en Toronto, mientras paseaba, para dejárselo a la amiga que visité. Esta es la historia de porque el nombre. Caminábamos cerca del río San Lorenzo, en Verdun, mirando el río, pasábamos por un puente rojo y gris y los árboles otoñales estaban pintados de rojo y amarillo, como describo en el poema. En el final del mismo dice “…yo ya había amado antes: amé muchos paisajes hace tiempo, amé cielos celestes y otros árboles…”

Aquí hago referencia a otro sitio, en la otra punta del mapa; hablo de otro río – el “Bug” en Polonia, donde he estado muchas veces (es uno de “mis sitios en el mundo” – y tengo algunos otros en mi corazón.) Allí también caminaba junto al río, en la campiña polaca, cerca de hermosos bosques y con bellos cielos, casas campesinas con techos negros de paja (algo bellisímo), diferente para mí que vivo en Buenos Aires, en el “Fin del Mundo” (como dice el Papa Francisco.) Pero ya entonces mis amigos polacos me decían que yo venia “del fin del mundo”, aunque al estar allí en Polonia, yo en broma les decía que yo estaba visitando “el fin del mundo…” Te confieso que no he encontrado el fin del mundo, por más que recorro no logro hallarlo. Curiosamente, el nombre de este río polaco que llega desde Rusia a Polonia quiere decir Dios, tal vez sea Él quien me lleve por estos lugares…¿? Lo cierto es que son lugares que están en mí por lo que he podido experimentar…

. . .

We asked the poet to talk about the name of her poem – Verdun. Here’s what Alicia told us:

“Verdun is after the Montreal borough of the same name. I lived there when I visited Canada – and fell in love with the country. The poem itself I wrote in Toronto, while passing through, to leave for the friend I’d visited. … So, in Montreal (Verdun) we were walking alongside the St. Lawrence River and we passed by a red and grey bridge, and there were autumn trees with leaves all yellow and red. After seeing this there came into my mind these words: “I had already loved before, long before, many landscapes, blue skies, other trees…” I was thinking then of another place, another point, on the map, and another river – the River “Bug” in Poland. I’ve been there many times – it’s one of my special places in this world – and I have a few others, too, in my heart. So I was walking along the “Bug”, in the Polish countryside, close to lovely woods, and a pretty sky overhead, and the rural houses with their black straw roofs – something so beautiful – and quite different for someone like me who lives in Buenos Aires (at “the End of the Earth”, as Pope Francis says.) I confess that I’ve yet to encounter “the End of the Earth”; as much as I’ve traversed the globe I haven’t attained such a feat! Oddly, the name of that Polish river – “Bug” – that flows between Russia and Poland – is supposed to mean “God”…and maybe it’s He who carries me to all these various places…? One thing’s certain: these places are “within me”, too, and I’ve been able to experiment with them…”

. . .

Translations from Spanish into English: Alexander Best

. . . . .

Jaime Sabines: “Message to Rosario Castellanos” / “Recado a Rosario Castellanos”

Posted: October 8, 2013 Filed under: English, Jaime Sabines, Spanish Comments Off on Jaime Sabines: “Message to Rosario Castellanos” / “Recado a Rosario Castellanos”Jaime Sabines (Chiapas, 1926 – México City, 1999)

“Message to Rosario Castellanos”

(Translation from Spanish into English: Paul Claudel and St.John Perse)

.

Only a fool could devote a whole life to solitude and love.

Only a fool could die by touching a lamp,

if a lighted lamp,

a lamp wasted in the daytime is what you were.

Double fool for being helpless, defenceless,

for going on offering your basket of fruit to the trees,

your water to the spring,

your heat to the desert,

your wings to the birds.

Double fool, double Chayito*, mother twice over,

to your son and to yourself.

Orphan and alone, as in the novels,

coming on like a tiger, little mouse,

hiding behind your smile,

wearing transparent armour,

quilts of velvet and of words,

over your shivering nakedness.

.

How I love you, Chayo*, how I hate to think

of them dragging your body – as I’m told they did.

Where did they leave your soul?

Can’t they scrape it off the lamp,

get it up off the floor with a broom?

Don’t they have brooms at the Embassy?

How I hate to think, I tell you, of them taking you,

laying you out, fixing you up, handling you,

dishonouring you with the funeral honours.

(Don’t give me any of that

Distinguished Persons fucking stuff!)

I hate to think of it, Chayito!

And this is all? Sure it’s all. All there is.

At least they said some good things in The Excelsior*

and I’m sure there were some who cried.

They’re going to devote supplements to you,

poems better than this one, essays, commentaries

– how famous you are, all of a sudden!

Next time we talk

I’ll tell you the rest.

.

I’m not angry now.

It’s very hot in Sinaloa.

I’m going down to have a drink at the pool.

.

*Chayito / Chayo – nicknames for the name Rosario i.e. Little Rosary/Rosa/Rosie

*El Excélsior – a México City daily newspaper

. . .

“Recado a Rosario Castellanos”

.

Sólo una tonta podía dedicar su vida a la soledad

y al amor.

Sólo una tonta podía morirse al tocar una lámpara,

si lámpara encendida,

desperdiciada lámpara de día eras tú.

Retonta por desvalida, por inerme,

por estar ofreciendo tu canasta de frutas a los árboles,

tu agua al manantial,

tu calor al desierto,

tus alas a los pájaros.

Retonta, re-Chayito, remadre de tu hijo y de ti misma.

Huérfana y sola como en las novelas,

presumiendo de tigre, ratoncito,

no dejándote ver por tu sonrisa,

poniéndote corazas transparentes,

colchas de terciopelo y de palabras

sobre tu desnudez estremecida.

.

¡Como te quiero, Chayo, como duele

pensar que traen tu cuerpo! – así se dice –

(¿Dónde dejaron tu alma? ¿ No es posible

rasparla de la lámpara,

recogerla del piso con una escoba?

¿Qué, no tiene escobas la Embajada?)

¡Cómo duele, te digo, que te traigan,

te pongan, te coloquen, te manejen,

te lleven de honra en honra funerarias!

(¡No me vayan a hacer a mi esa cosa

de los Hombres Ilustres, con una chingada!)

¡Como duele, Chayito!

¿Y esto es todo? ¡ Claro que es todo, es todo!

Lo bueno es que hablan bien en el Excélsior

y estoy seguro de que algunos lloran,

te van a dedicar tus suplementos,

poemas mejores que éste, estudios, glosas,

¡qué gran publicidad tienes ahora!

La próxima vez que platiquemos

te diré todo el resto.

.

Ya no estoy enojado.

Hace mucho calor en Sinaloa.

Voy a irme a la alberca a echarme un trago.

. . .

Rosario Castellanos – poet, author, essayist – was born into a “Ladino” (Hispanicized Mestizo) landowning family in Chiapas. From her mid-teens onward she lived in México City, where she would gradually become one of the so-called “Generation of 1950” – post-War writers of Latin America. Throughout her life – cut short by a freak domestic electrical accident involving a lamp while she was leaving her bath in Tel Aviv – where she had been posted as Mexican ambassador – she wrote with passion and precision about what now we would call “cultural and gender oppression”. Her 1962 novel Oficio de Tinieblas(The Book of Lamentations in its English translation) is an empathetic yet trenchant imagining of the conflicts between Tzotzil Mayans and “Ladinos” leading up to agrarian reform in her ancestral Chiapas. Castellanos is important today for opening the doors to a Mexican Feminist world-view through her frank and insightful poetry, novels, and newspaper essays.

. . .

Rosario Castellanos – poeta y novelista – nació en la Ciudad de México en 1925. Su infancia y parte de su adolescencia la vivió en Comitán y en San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas.

Dedicó una parte de su obra y de sus energías a la defensa de los derechos de las mujeres, labor por la que es recordada como uno de los símbolos del feminismo latinoamericano. A nivel personal, su propia vida estuvo marcada por un matrimonio infeliz y depresiones múltiples que la llevaron en más de una ocasión a ser ingresada.

Su obra incluye la novela Oficio de Tinieblas (1962) – trata de reforma agraria y tensiones sociales entre los tzotziles y los ladinos en el campo de Chiapas – también el poemario Poesía no eres tú (1972).

En 1971, Castellanos fue nombrada embajadora de México en Israel, desempeñándose como catedrática en la Universidad Hebrea de Jerusalén, además de su labor de diplomática. Falleció en Tel Aviv en agosto de 1974 – a consecuencia de una descarga eléctrica provocada por una lámpara cuando acudía a contestar el teléfono al salir de bañarse. Sus restos fueron trasladados a La Rotonda de los Hombres Ilustres (ahora La Rotonda de las Personas Ilustres) en la Ciudad de México.

. . . . .

Jaime Sabines: “Before the ice of silence descends on my tongue…” / “Antes de que caiga sobre mi lengua el hielo del silencio…”

Posted: October 8, 2013 Filed under: English, Jaime Sabines, Spanish Comments Off on Jaime Sabines: “Before the ice of silence descends on my tongue…” / “Antes de que caiga sobre mi lengua el hielo del silencio…”Jaime Sabines (Born in Chiapas, 1926 – died in México City, 1999)

. . .

“On Hope”

.

Occupy yourselves here with hope.

The joy of the day that’s coming

buds in your eyes like a new light.

But that day that’s coming isn’t going to come: this is it.

. . .

“De la esperanza”

.

Entreteneos aquí con la esperanza.

Es júbilo del día que vendrá

os germina en los ojos como una luz reciente.

Pero ese día que vendrá no ha de venir: es éste.

. . .

“On Illusion”

.

On the tablet of my heart you wrote:

Desire.

And I walked for days and days,

mad and scented and dejected.

.

“De la ilusión”

.

Escribiste en la tabla de mi corazón:

Desea.

Y yo anduve días y días,

loco, aromado, y triste.

. . .

“On Death”

.

Bury it.

There are many silent men under the earth

who will take care of it.

Don’t leave it here.

Bury it.

“De la muerte”

.

Enterradla.

Hay muchos hombres quietos, bajo tierra,

que han de cuidarla.

No la dejéis aquí –

Enterradla.

. . .

“On Myth”

.

My mother told me that I cried in her womb.

They said to her: he’ll be lucky.

.

Someone spoke to me all the days of my life

into my ear, slowly, taking their time.

Said to me: live, live, live!

It was Death.

.

“Del mito”

.

Mi madre me contó que yo lloré en su vientre.

A ella le dijeron: tendrá suerte.

.

Alguien me habló todos los días de mi vida

al oído, despacio, lentamente.

Me dijo: ¡vive, vive, vive!

Era la Muerte.

. . .

If I were going to die in a moment, I would write these words of wisdom: tree of bread and honey, rhubarb, coca-cola, zonite, swastika. And then I would start to cry.

.

You can start to cry even at the word “excused” if you want to cry.

.

And this is how it is with me now. I’m ready to give up even my fingernails, to take out my eyes and squeeze them like lemons over the cup of coffee.

(“Let’s have a cup of coffee with eye peel, My Heart”).

.

Before the ice of silence descends on my tongue, before my throat splits and my heart keels over like a leather sack, I want to tell you, My Life, how grateful I am for this stupendous liver that let me eat all your roses on the day when I got into your hidden garden without anyone seeing me.

.

I remember it. I filled my heart with diamonds – they are fallen stars that have aged in the dust of the earth – and it kept jingling like a tambourine when I laughed. The only thing that really annoys me is that I could have been born sooner and I didn’t do it.

.

Don’t put love into my hands like a dead bird.

Si hubiera de morir dentro de unos instantes, escribiría estas sabias palabras: árbol del pan y de la miel, ruibarbo, coca-cola, zonite, cruz gamada. Y me echaría a llorar.

.

Uno puede llorar hasta con la palabra “excusado” si tiene ganas de llorar.

.

Y esto es lo que hoy me pasa. Estoy dispuesto a perder hasta las uñas, a sacarme los ojos y a exprimirlos como limones sobre la taza de café.

(“Te convido a una taza de café con cascaritas de ojo, corazón mío”).

.

Antes de que caiga sobre mi lengua el hielo del silencio, antes de que se raje mi garganta y mi corazón se desplome como una bolsa de cuero, quiero decirte, vida mía, lo agradecido que estoy, por este higado estupendo que me dejó comer todas tus rosas, el día que entré a tu jardín oculto sin que nadie me viera.

.

Lo recuerdo. Me llené el corazón de diamantes – que son estrellas caídas y envejecidas en el polvo de la tierra – y lo anduve sonando como una sonaja mientras reía. No tengo otro rencor que el que tengo, y eso porque pude nacer antes y no lo hiciste.

.

No pongas el amor en mis manos como un pájaro muerto.

I take pleasure in the way the rain beats its wings on the back of the floating city.

.

The dust comes down. The air is left clean, crossed by leaves of odour, by birds of coolness, by dreams. The sky receives the city that is being born.

.

Streetcars, buses, trucks, people on bicycles and on foot, carts of all colours, street-vendors, bakers, pots of tamales, grilles of baked bananas, balls flying between one child and another: the streets swell, the sounds of voices multiply in the last light of the day hung up to dry.

.

They come out like ants after the rain, to pick up the crumb of the sky, the little straw of eternity to take away to their dark houses, with cuttlefish hanging from the roofs, with weaving spiders under the beds, and with one familiar ghost, at least, in back of some door.

.

Thanks be to you, Mother of the Black Clouds, who have so whitened the face of the afternoon and have helped us to go on loving life.

. . .

Me gustan los aletazos de la lluvia sobre los lomos de la ciudad flotante.

.

Desciende del polvo. El aire queda limpio, atravesado de hojas de olor, de pájaros de frescura, de sueños. El cielo recibe a la ciudad naciente.

.

Tranvías, autobuses, camiones, gentes en bicicleta y a pie, carritos de colores, vendedores ambulantes, panaderos, ollas de tamales, parrillas de plátanos horneados, pelotas de un niño al otro: crecen las calles, se multiplican los rumores en las últimas luces del día puesto a secar.

.

Salen, como las hormigas después de la lluvia, a recoger la migas del cielo, la pajita de la eternidad que han de llevarse a sus casas sombrías, con pulpos colgando del techo, con arañas tejedoras debajo de la cama, y con un fantasma familiar, cuando menos, detrás de alguna puerta.

.

Gracias te son dadas, Madre de las Nubes Negras, que has puesto tan blanca la cara de la tarde y que nos has ayudado a seguir amando la vida.

. . .

Before long you will offer these pages to people you don’t know as though you were holding out a handful of grass that you had cut.

.

Proud and depressed of your achievement you will come back and fling yourself into your favourite corner.

.

You call yourself a poet because you don’t have enough modesty to remain silent.

.

Good luck to you, thief, with what you’re stealing from your suffering – and your loves! Let’s see what sort of image you make out of the pieces of your shadow you pick up.

. . .

Dentro de poco vas a ofrecer estas páginas a los desconocidos como si extendieras en la mano un manojo de hierbas que tú cortaste.

.

Ufano y acongojado de tu proeza, regresarás a echarte al rincón preferido.

.

Dices que eres poeta porque no tienes el pudor necesario del silencio.

.

¡Bien te vaya, ladrón, con lo que le robas a tu dolor y a tus amores! ¡A ver qué imagen haces de ti mismo con los pedazos que recoges de tu sombra!

.

You have what I look for, what I long for, what I love – you have it.

The fist of my heart is beating, calling.

I thank the stories for you.

I thank your mother and your father and death who has not seen you.

I thank the air for you.

You are elegant as wheat,

delicate as the outline of your body.

I have never loved a slender woman

but you have made my hands fall in love,

you moored my desire,

you caught my eyes like two fish.

And for this I am at your door, waiting.

. . .

Tú tienes lo que busco, lo que deseo, lo que amo – tú lo tienes.

El puño de mi corazón está golpeando, llamando.

Te agradezco a lo cuentos,

doy gracias a tu madre y a tu padre,

y a lo muerte que no te ha visto.

Te agradezco al aire.

Eres esbelta como el trigo,

frágil como la línea du tu cuerpo.

Nunca he amado a mujer delgada

pero tú has enamorado mis manos,

ataste mi deseo,

cogiste mis ojos como dos peces.

Por eso estoy a tu puerta, esperando.

. . .

From: Selected Poems of Jaime Sabines: Pieces of Shadow

Translations from Spanish into English © W.S. Merwin (1995)

.

. . .

Jaime Sabines (1926-1999) was born in Tuxtla Gutiérrez in the state of Chiapas, México.

At 19 he moved to México City, studying Medicine for three years, then switching to Philosophy and Literature at UNAM (University of México). He published eight volumes of poetry, including Horal (1950), Tarumba (1956), and Maltiempo (1972), receiving the Xavier Villaurrutia Award for the latter. He was granted the Chiapas Prize in 1959 and the National Literature Award in 1983. He also served as a congressman for Chiapas. Octavio Paz called Sabines one of the handful of poets that comprised the beginning of Modern Latin-American Poetry. For such poets the aim of the poem was not – as before – to invent, rather to explore. In a 1970s interview Sabines observed: “No subject matter can be forced upon the poet. He must be a witness to his times. Must discover reality and recreate it. He should speak of that which he lives and experiences. I feel that a poet must first of all be authentic; I mean by this that there must be a correspondence between his personal world and the world that surrounds him. If you have a mystical inclination – why not write about it? If you live alone and are afflicted by your solitude – why not speak about it, if it is yours? Poetry must bear witness to our everyday lives.”

.

La obra de Jaime Sabines (1926-1999) representa, dentro de la poesía mexicana contemporánea, una isla que se vincula con la realidad a través de puentes inexorables: la muerte, la inquietud social, la angustia por la existencia, la presencia o la ausencia de Dios y – fundamentalmente – el amor. El amor es – en un poema de Sabines – no sólo un sentimiento sino también una herramienta – un clave personal – para comunicarse no sólo con la mujer sino con el mundo. Sabines fue el más notable precursor de la poesía coloquial en América Latina. (Mario Benedetti, 2007)

. . . . .

“Esta canção ardente”: “Quenguelequêze!” de Rui de Noronha

Posted: October 1, 2013 Filed under: Portuguese, Rui de Noronha | Tags: Poetas africanos Comments Off on “Esta canção ardente”: “Quenguelequêze!” de Rui de NoronhaRui de Noronha

(poeta e contista, Maputo, Moçambique, 1909 – 1943)

“Quenguelequêze!”

.

Durante o período de reclusão, que vai do nascimento à queda do cordão umbilical das crianças, o pai não pode entrar na palhota sob pretexto algum e ao amante da mãe de uma criança ilegítima é vedado, sob pena de a criança morrer, passar nesse período defronte da palhota. O período de reclusão, entre albumas famílias de barongas, é levado até ao aparecimento da primeira lua nova, dia de grande regozijo e em que a criança, depois de uma cerimónia especial denominada “iandlba”, aparece publicamente na aldeia, livre da poluição da mãe.

.

Quenguelequêze!… Quenguelequêze!…

Quenguelequêêêzeee

Quenguelequêêêzeee

.

Na tarde desse dia de janeiro

Um rude caminheiro

Chegara à aldeia fatigado

De um dia de jornada.

E acordado

Contara que descera à noite a velha estrada

Por onde outrora caminhara Guambe

E vento não achando a erva agora lambe

Desde o nascer do sol ao despontar de lua,

Areia dura e nua.

.

Depois bebera a água quente e suja

Onde o mulói pousou o seu cachimbo outrora,

Ouvira, caminhando, o canto da coruja

E quase ao pé do mar lhe surpreendera a aurora.

.

Quenguelequêze!… Quenguelequêze!…

Quenguelequêêêzeee

.

Pisara muito tempo uma vermelha areia,

E àquela dura hora à qual o sol apruma

Uma mulher lhe deu numa pequena aldeia

Um pouco de água e “fuma”.

.

guelequêêêzeee!…

.

Descera o vale. O sol quase cansado

Desenrolara esteiras

Que caíram silentes pelo prado

Cobrindo até distante as maçaleiras…

.

Quenguelequêêê…

.

Vinha pedir pousada

Ficava ainda distante o fim de sua jornada,

Lá muito para baixo, a terra onde os parentes

Tinham ido buscar os ouros reluzentes

Para comprar mulheres, pano e gado

E não tinham voltado…

.

Quenguelequêze! Quenguelequêêêze!…

Surgira a lua nova

E a grande nova

Quenguelequêze! ia de boca em boca

Numa alegria enorme, numa alegria louca,

Traçando os rostos de expressões estranhas

Atravessando o bosque, aldeias e montanhas,

Loucamente…

Perturbadoramente…

Danças fantásticas

Punham nos corpos vibrações elásticas,

Febris,

Ondeando ventres, troncos nus, quadris…

E ao som das palmas

Os homents cabriolando

Iam cantando

.

Medos de estranhas, vingativas almas,

Guerras antigas

Com destemidas ímpias inimigas

E obscenidades claras, descaradas,

Que as mulheres ouviam com risadas

Ateando mais e mais

O rítmico calor das danças sensuais.

.

Quenguelequêze!… Quenguelequêze!…

.

Uma mulher de quando em quando vinha

Coleava a espinha,

Gingava as ancas voluptuosamente

E posta diante do homem, frente a frente,

Punha-se a simular os conjugais segredos.

Nos arvoredos

la um murmúrio eólico

Que dava à cena, à luz da lua um quê diabólico…

Queeezeee… Quenguelequêêêzeee!…

.

Entanto uma mulher saíra sorrateira

Com outra mais velhinha,

Dirigira-se na sombra à montureira

Com uma criancinha.

Fazia escuro e havia ali um cheiro estranho

A cinzas ensopadas,

Sobras de peixe e fezes de rebanho

Misturadas…

O vento perpassando a cerca de caniço

Trazia para fora um ar abafadiço

Um ar de podridão…

E as mulheres entraram com um tição.

E enquanto a mais idosa

Pegava criança e a mostrava à lua

Dizendo-lhe: “Olha, é a tua”,

A outra erguendo a mão

.

Lançou direita à lua a acha luminosa

O estrepitar das palmas foi morrendo

A lua foi crescendo… foi crescendo

Lentamente…

Como se fora em branco e afofado leito

Deitaram a criança rebolando-a

Na cinza de monturo.

E de repente,

Quando chorou, a mãe arrebatando-a

Ali, na imunda podridão, no escuro

Lhe deu o peito

O pai então chegou,

Cercou-a de desvelos,

De manso a conduziu com [sic] os cotovelos

Depois tomou-a nos braços e cantou

Esta canção ardente:

Meu filho, eu estou contente.

Agora já não temo que ninguém

Mofe de ti na rua

E diga, quando errares, que tua mãe

Te não mostrou à lua.

Agora tens abertos os ouvidos

P’ra tudo compreender.

Teu peito afoitará impávido os rugidos

Das feras sem tremer.

Meu filho, eu estou contente

Tu és agora um ser inteligente.

E assim hás-de crescer, hás-de ser homem forte

Até que já cansado

Um dia muito velho

De filhos rodeado,

Sentindo já dobrar-se o teu joelho

Virá buscar-te a Morte…

Meu filho, eu estou contente.

Meu susto já lá vai.

.

Entanto o caminheiro olhou para a criança,

Olhou bem as feições, a estranha semelhança,

E foi-se embora.

Na aldeia, lentamente,

O estrepitar das palmas foi morrendo…

E a lua foi crescendo…

Foi crescendo…

Como um ai…

.

Quando rompeu ao outro dia a aurora

Ia já longe… muito longe… o verdadeiro pai…

. . .

António Rui de Noronha nasceu na então Lourenço Marques – atual Maputo – Moçambique, em 1909. Mestiço, de pai indiano, de origem brâmane, e de mãe negra, foi funcionário público (Serviço de Portos e Caminho de Ferro) e jornalista. O autor colaborou na imprensa escrita de Moçambique, notadamente em O Brado Africano, com apenas 17 anos de idade. Esta produção inicial, que se reduziram apenas a três contos, e que correspondem ainda a uma fase de afirmação literária, virá a ser prosseguida a partir de 1932, com uma intervenção mais activa na vida do jornal, chegando mesmo a integrar o seu corpo directivo.

Uma desilusão amorosa, causada pelo preconceito racial, fez, segundo os seus amigos, com que o escritor se deixasse morrer no hospital da capital de Moçambique, com 34 anos, em 1943.

Seu professor de Frances, Dr. Domingos Reis Costa reuniu, selecionou e revisou 60 poemas para a edição póstuma intitulada Sonetos (1946), editado pela tipografia Minerva Central.

Sua obra completa está reunida em Os meus versos, publicada em 2006, com organização, notas e comentários de Fátima Mendonça.

Rui de Noronha é considerado o precursor (mais jovem) da poesia moderna Moçambicana.

. . . . .

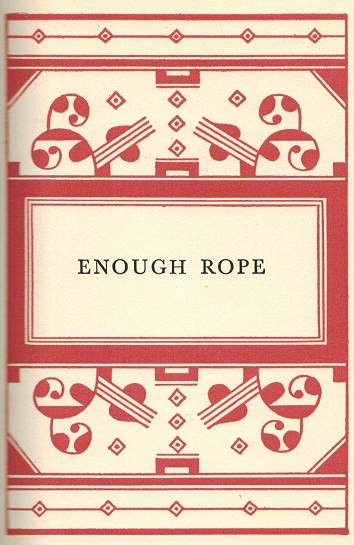

Ralph Carmichael: “Un lugar tranquilo” / “A Quiet Place”

Posted: October 1, 2013 Filed under: English, Ralph Carmichael, Spanish, Translator's Whimsy: Song Lyrics / Extravagancia del traductor: Letras de canciones traducidas por Alexander Best, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Ralph Carmichael: “Un lugar tranquilo” / “A Quiet Place”.

Ralph Carmichael (Compositor góspel, nacido 1927)

“Un lugar tranquilo”

.

Hay un lugar tranquilo

lejos del paso raudo

donde Dios puede calmar mi mente afligida.

Guardado por árbol y flor,

está allí que dejo atrás mis penas

durante la hora quieta con Él.

.

En un jardín pequeño

o alta montaña,

Encuentro allí

una nueva fortaleza

y mucho ánimo.

.

Y luego salgo de ese lugar sereno

bien listo para enfrentar un nuevo día

con amor por toda la raza humana.

. . .

Ralph Carmichael es un compositor de canciones ‘pop’ / cristianas contemporáneas.

Su canción “A Quiet Place” (“Un lugar tranquilo”) fue adaptada por un cantautor góspel estadounidense, Mervyn Warren, con su grupo “a capela” cristiano, Take 6, organizado en la Universidad Adventista Oakwood, de Huntsville, Alabama, EE.UU., durante los años 80. El arreglo musical de Señor Warren – hecho para seis voces en 1988 – es exquisitamente dulce y sensitivo. Éste no es el sonido tradicional de la música góspel, sino algo afinado y jazzístico.

Escuche la canción (versión original en inglés) en este videoclip del Festival de Jazz de Vitoria-Gasteiz (País Vasco, 1997):

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SH2orpg6ww4

. . .

Ralph Carmichael (born 1927)

“A Quiet Place” (1969)

.

There is a quiet place

far from the rapid pace

where God can soothe my troubled mind.

.

Sheltered by tree and flower

there in my quiet hour with Him

my cares are left behind.

.

Whether a garden small

or on a mountain tall

new strength and courage there I find.

.

And then from that quiet place

I go prepared to face a new day

with love for all mankind.

. . .

Ralph Carmichael is a composer and arranger of both pop music and contemporary Christian songs.

From 1962 to 1964 he arranged music for Nat King Cole, including Cole’s final hit, “L-O-V-E”.

“A Quiet Place” dates from 1969.

Mervyn Warren and Claude McKnight arranged a number of Christian songs – both traditional and “new” – for their six-part-harmony “barbershop”-style Gospel vocal sextet, Take 6.

Take 6 was formed at the Seventh-Day-Adventist college, Oakwood University, in Huntsville, Alabama in the early 1980s.

Mervyn Warren – most especially – is responsible for the exquisitely tender or playful harmonies that characterize Take 6’s unique sound. His 1988 arrangement of “A Quiet Place” is a good example of his genius as arranger. Astonishingly, Warren’s magnificent arrangements were never published or transcribed – all members learned their harmonies “in the moment” – through many hours of vocal jamming and experiment. Warren later left the group because the revelation of his homosexuality put him at cross-purposes with the Seventh-Day-Adventist credo.

Listen to Take 6 perform “A Quiet Place” (Mervyn Warren’s arrangement) on the following YouTube clip from a 1997 concert in Spain at the Festival de Jazz de Vitoria Gasteiz – their unusual Gospel sound is belovéd of Jazz aficionados, too!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SH2orpg6ww4

. . . . .

Classic Kaiso: “Bass Man” by The Mighty Shadow

Posted: August 31, 2013 Filed under: English, English: Trinidadian, Winston Anthony Bailey Comments Off on Classic Kaiso: “Bass Man” by The Mighty Shadow ZP_The Mighty Shadow_photograph by Abigail Hadeed

ZP_The Mighty Shadow_photograph by Abigail Hadeed

.

August 31st is Independence Day in Trinidad and Tobago, and, since “we” [here at Zócalo Poets] have a sentimental attachment to Kaiso, let “us” therefore share the lyrics to an old favourite – “Bassman” by The Mighty Shadow (Winston Anthony Bailey, born 1941, Belmont, Port of Spain) – which, back in 1974, was a strikingly original Calypso tune with a new sound and instrumental arrangement: bandy-leggéd rhythms + a bunny-hoppity bass-line.

Influenced by the style of The Mighty Spoiler (Theophilus Phillip, 1926-1960), who was a great exponent of humorous and imaginative Calypsos, Shadow has had a propensity for the eccentric and the eery. Often, he has worn dark clothing with a broad-brimmed hat and regal cape; and he has the most curious movements – including a minimalist approach – when it comes to his deportment while performing. Winning first and second places in the contest for Road March 1974 – with his songs “Bassman” and “Ah Come Out To Play” – released as a 7-inch 45rpm single vinyl record the same year – Shadow was the ‘new’ calypsonian to break the stranglehold on Road March Title held for eleven years by “biggies” Kitchener and Sparrow. While Shadow came very close to winning Calypso Monarch for 1974 – certainly he was the crowd favourite – the judges didn’t agree. He would be denied the crown several seasons over before deciding to just ignore that competition – well, for 17 years, at any rate. In 1993 he re-entered for Calypso Monarch and, though he was not to win, he would comment afterwards: “I never get no crown, but they can’t touch my music. The Shadow music sweet too bad.” However, in 2000, he did finally win the Monarch title – something he’d been deserving of for many years.

As regards his musical contribution to the Calypso genre, Shadow told the Trinidad newspaper, TnT Mirror, in 1989, that his claim to fame was in “moving the bottom of the music, and introducing changes in the bass lines…My music is characterized by a lot of energy, because of my emphasis on the foot drums and bass…” Among The Mighty Shadow‘s famous songs are: Obeah (1982), Ah Come Out Tuh Party (1983), If I Wine I Wine (1985), The Garden Want Water (1988), and Mr. Brown (1996).

ZP_A 12 year old boy and member of the Tamana Pioneers steel orchestra practises his bass drums_ Arima, Trinidad_ January 2013

ZP_A 12 year old boy and member of the Tamana Pioneers steel orchestra practises his bass drums_ Arima, Trinidad_ January 2013

. . .

Winston Anthony Bailey a.k.a. The Mighty Shadow

“Bass Man”

(Music and lyrics by Bailey / Arranger: Art de Coteau)

.

I was planning to forget Calypso

And go and plant peas in Tobago

But I am afraid ah cyah make de grade.

Cuz every night I lie down in mih bed

Ah hearing a Bassman in mih head

.

Ah don’t know how dis t’ing get inside me

But e-ve-ry morning, he drivin’ me crazy

Like he takin’ me head for a pan-yard

Morning and evening, like dis fella gone mad.

Pim pom – an’ if ah don’t want to sing

Pim pom – well, he start to do he t’ing

I don’t want to – but ah have to sing

Pim pom – an’ if ah don’t want to dance

Pim pom – he does have me in a trance

I don’t want to – but ah have to prance to his:

pom pom pidi pom, pom, pom pom pidi pom, pom…

.

One night I said to de Bassman

Give me your identification

He said “Is me – Farrell –

Your Bassman from hell.

Yuh tell me you singing Calypso

An’ ah come up to pull some notes for you.”

.

Ah don’t know how dis t’ing get inside me

But e-ve-ry morning, he drivin’ me crazy

Like he takin’ me head for a pan-yard

Morning and evening, like dis fella gone mad.

Pim pom – an’ if ah don’t want to sing

Pim pom – well, he start to pull he string

I don’t want to – but ah have to sing

Pim pom – an’ if ah don’t want to dance

Pim pom – he does have me in a trance

I don’t want to – but ah have to prance to his:

pom pom pidi pom, pom, pom pom pidi pom, pom…

.

I went and ah tell Dr Lee Yeung

That I want a brain operation

A man in meh head

I want him to dead

He said it’s my imagination

But I know ah hearin’ de Bassman…

Ah don’t know how dis t’ing get inside me

But e-ve-ry morning, he drivin’ me crazy

Like he takin’ me head for a pan-yard

Morning and evening, like dis fella gone mad.

Pim pom – etcetera…..

. . . . .

Véronique Tadjo: “Cocodrilo” / “Crocodile”

Posted: August 27, 2013 Filed under: English, French, Spanish, Véronique Tadjo, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Véronique Tadjo: “Cocodrilo” / “Crocodile”

Véronique Tadjo (nacido en 1955, Paris/Abidjan, Costa de Marfil)

“Cocodrilo”

.

No es la vida fácil ser un cocodrilo

especialmente si no quiere ser un cocodrilo

El coco que usted puede ver – en la página opuesta* –

no es feliz en su

piel de coco

Era su preferencia

ser diferente

Habría preferido

llamar la atención de

Los niños

y jugar con ellos

Platicar con sus padres

Dar paseos

por la aldea

Excepto, excepto, excepto…

.

Cada vez que sale del agua

Los pescadores

tiran lanzas

Los niños

huyen

Las muchachas

abandonan sus jarros

.

Su vida es

una vida

de soledad y de la pena

Vida sin cuate y sin cariño,

sin ningún lugar a visitar

.

En todas partes – Desconocidos

.

Ese cocodrilo

Vegetariano

Un cocodrilo

y bueno para nada

Un cocodrilo

que se siente un

Horror sagrado de la sangre

.

Por favor:

Escríbale,

Escríbale a:

Cocodrilo Amable,

Caleta número 3,

Cuenca del Rio Níger.

.

*La versión original en francés presenta un dibujo hecho por Señora Tadjo.

.

Traducción en español: Alexander Best

. . .

Véronique Tadjo (née en 1955, Paris/Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire)

“Crocodile”

.

Ce n’est pas facile d’être un crocodile

Surtout si on na’a pas envie

D’être un crocodile

Celui que vous voyez

Sur la page opposée

N’est pas bien

Dans sa peau

De croco

il aurait aimé

Etre different

Il aurait aimé

Attirer

Les enfants

Jouer

Avec eux

Converser

avec les parents

Se balader

Dans

Le village

Mais, mais, mais

.

Quand il sort

De l’eau

Les pêcheurs

Lancent des sagaies

Les gamins

Détalent

Les jeunes filles

Abandonnent leurs canaris

.

Sa vie

Est une vie

De solitude

Et de tristesse

.

Sans ami

Sans caresse

Nulle part

Où aller

.

Partout –

Etranger

.

Un crocodile

Crocodile

Végétarien

Et bon à rien

Qui a

Une sainte horreur

Du sang

.

S’il vous plaît

Ecrivez,

Ecrivez à:

Gentil Crocodile,

Baie Numéro 3,

Fleuve Niger.

. . .

Véronique Tadjo (born 1955, Paris/Abidjan, Ivory Coast)

“Crocodile”

.

It’s not easy to be a crocodile

Especially if you don’t want

To be a crocodile

The one you see

On the opposite page*

Is not happy

in his croc’s

Skin

He would have liked

To be different

He would have liked

To attract

Children

Play

with them

Talk

With their parents

Walk around

in the village

But, but, but

.

When he comes out

Of the water

Fisherman

Throw spears

Children

Take off

Young girls

Abandon their water jugs

.

His life

Is a life

Of solitude

And sadness

.

Without a friend

Without affection

Nowhere

To go

.

Everywhere

Strangers

.

A Crocodile

Vegetarian

Crocodile

And good for nothing

Who has

A holy horror

Of blood

.

Please

Write,

Write to:

Nice Crocodile,

Bay Number 3,

Niger River.

.

*The original French-language version of this poem featured a drawing by Tadjo herself of a crocodile.

. . . . .