Jane Kenyon: Al solsticio de invierno / At the winter solstice

Posted: December 21, 2014 Filed under: English, Jane Kenyon, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Jane Kenyon: Al solsticio de invierno / At the winter solsticeJane Kenyon

Al solsticio de invierno

.

Los pinos parecen negros en la media-luz del alba.

Quietud…

Mientras dormíamos, una pulgada de nieve simplificó el campo.

Hoy, entre todos los días, el sol no brillará más que es meramente necesario.

.

Anoche, dentro la iglesia del pueblito, los niños

– pastores y sabios –

empujaron cerca el pesebre, en obedencia, deseando solo que pasa el tiempo.

La niña vestido como María se estremecía – agachándose sobre el heno acre;

y – como la Madre del Cristo – se preguntaba por que ella estaba La Elegida.

.

Después del cuadro vivo: un alboroto de tarjetas, regalos y dulces navideños…

Algunos se quedaron para despejar de los bancos los fragmentos y cintas vividas;

también para levantar a su sitio tradicional el púlpito.

.

Cuando abrí la biblia centenaria por leer el cuento de Luca sobre la Epifania,

polvo negro de la encuadernación cayó sobre mis manos – y el mantel.

. . .

Jane Kenyon

At the winter solstice

.

The pines look black in the half-

light of dawn. Stillness…

While we slept an inch of new snow

simplified the field. Today of all days

the sun will shine no more

than is strictly necessary.

.

At the village church last night

the boys – shepherds and wisemen –

pressed close to the manger in obedience,

wishing only for time to pass;

but the girl dressed as Mary trembled

as she leaned over the pungent hay,

and like the mother of Christ

wondered why she had been chosen.

.

After the pageant, a ruckus of cards,

presents, and homemade Christmas sweets.

A few of us stayed to clear the bright

scraps and ribbons from the pews,

and lift the pulpit back into place.

.

When I opened the hundred-year-old Bible

to Luke’s account of the Epiphany

black dust from the binding rubbed off

on my hands, and on the altar cloth.

.

1990

. . .

Otros poemas por Jane Kenyon:

https://zocalopoets.com/2014/11/20/jane-kenyon-poemas-intimos-sobre-un-esposo/

.

https://zocalopoets.com/2014/11/20/winter-arrives-three-poems-by-jane-kenyon/

. . . . .

Claude McKay: The Flame Heart

Posted: December 21, 2014 Filed under: Claude McKay, English Comments Off on Claude McKay: The Flame HeartClaude McKay (Jamaica/U.S.A., 1889-1948)

The Flame Heart

.

SO much have I forgotten in ten years,

So much in ten brief years! I have forgot

What time the purple apples come to juice,

And what month brings the shy forget-me-not.

I have forgot the special, startling season

Of the pimento’s flowering and fruiting;

What time of year the ground doves brown the fields

And fill the noonday with their curious fluting.

I have forgotten much, but still remember

The poinsettia’s red, blood-red in warm December.

.

I still recall the honey-fever grass,

But cannot recollect the high days when

We rooted them out of the ping-wing path

To stop the mad bees in the rabbit pen.

I often try to think in what sweet month

The languid painted ladies used to dapple

The yellow by-road mazing from the main,

Sweet with the golden threads of the rose-apple.

I have forgotten–strange–but quite remember

The poinsettia’s red, blood-red in warm December.

.

What weeks, what months, what time of the mild year

We cheated school to have our fling at tops?

What days our wine-thrilled bodies pulsed with joy

Feasting upon blackberries in the copse?

Oh some I know! I have embalmed the days

Even the sacred moments when we played,

All innocent of passion, uncorrupt,

At noon and evening in the flame-heart’s shade.

We were so happy, happy, I remember,

Beneath the poinsettia’s red in warm December.

. . . . .

Pro-Sex Poems of Love and Desire: Lenore, Nikki, Olga, Maxine

Posted: December 10, 2014 Filed under: English, Lenore Kandel, Maxine Kumin Comments Off on Pro-Sex Poems of Love and Desire: Lenore, Nikki, Olga, MaxineExcerpts from Antoinette May’s 1967 interview with Lenore Kandel in Les Gals magazine, Summer 1967 issue, volume 2, number 3:

Late last year (1966) Lenore and her poetic description of the love act [using the word FUCK (ZP editor)] made headlines.

Lenore’s new book, published by Grove Press, is called, “Word Alchemy”.

“Word” is a four letter word, but hardly controversial. Alchemy might be more promising. With this in mind Les Gals editor Antoinette May climbed the three steep winding flights of stairs to Lenore’s apartment situated above a North Beach laundry.

The rooms that Lenore shares with her husband are musty, dusty and dark. “I don’t worry about inanimate things,” she explained unnecessarily. Once the latent housewife in Antoinette overcame the desire to tidy up, she became aware of the casual comfort of the place. Indian hangings and tapestries dominated the decor which definitely inclined one to recline for repose or anything else. The place had a definite lived-in, loved-in look that seemed pleasant and appropriate.

Lenore’s “Love Book” provoked numerous individuals (including the San Francisco pornography squad) not so much because of its subject matter, but, rather, by its choice of words.

Many people took offence when they found words heretofore confined to sidewalks and school desks suddenly appearing in printed books. Their outrage resulted in a lengthy court trial and the conviction of three booksellers. Lenore herself was not on trial, although everyone, including the judge, had difficulty remembering the fact.

LES GALS: Was shock appeal what it’s all about?

LENORE: Certainly not. I used that particular verb [FUCK (ZP editor)] because our English vocabulary is very limited. To intercourse with love just doesn’t sound right . Fornicate and copulate seem so medical.

LES GALS: Yes, but the verb you chose is an offence to a vast number of people.

LENORE: That’s because a word with a beautiful meaning—for two bodies to join through passion and love—has become aggressive. It’s a put-down word now, not a love word.

LES GALS: But don’t you think that by using the word so freely in your book, you’ll detract even more from its very special power and intimacy?

LENORE: No, if everyone used it appropriately—as a love word—it would be heard less.

. . .

LES GALS: Were you surprised by the guilty verdict?

LENORE: I was surprised that it was unanimous. It’s frightening. Police censorship is disrespectful to people. People should be allowed to make up their own minds. For some reason it’s okay to to sell black garter magazines that depict sex as something to snigger over. The movie ads—no matter how vulgar—are allowed as well, because they’re admittedly ‘bad’. Where I got in trouble was in saying that sex and the spirit are both beautiful parts of nature and equally divine. I don’t think there has been a trial since Salem where the words blasphemy or sacrilege have been used.

LES GALS: In the introduction to your new book –“Word Alchemy”– you are quoted as saying your favourite word is “yes”. Do you believe in sex for sex’s sake”?

LENORE: Sexuality with someone you love is far more than a physical act—but that doesn’t mean I’m putting down the physical act. I just want something more than that.

LES GALS: One witness for the defence said that reading your book would help married couples perform the love act better. Do you believe this?

LENORE: Not necessarily perform better, but I do think it could help them communicate better. Married people have so many hassles because they can’t communicate. It’s a terrible thing that two people who should be closest to each other often aren’t. So many men get this good girl-bad girl hangup. They have certain desires that they should express to their wives but instead they fulfill themselves with someone else. This is wrong and unnecessary.

. . .

LES GALS: If you had children would you allow them to read “The Love Book”?

LENORE: I think the important thing is to tell the truth. If children grow up in the environment where truth is a part of life they won’t have dirty minds. There’s certainly nothing harmful in my book, but an honest parent might say to a very small child, “This is a book you’ll understand and enjoy when you are older.” Children mature at different levels. It really depends on the individual. I think it’s a strange thing in our culture that death and torture are acceptable—children can see it everywhere they look—yet the love and tenderness between a man and a woman is something to conceal and feel guilty about. I think this must be very confusing to children.

Lenore Kandel (1932-2009)

Invocation for Mitreya (from the collection Word Alchemy, 1967)

.

To invoke the divinity in man with the mutual gift of love

with love as animate and bright as death

the alchemical transfiguration of two separate entities

into one efflorescent deity made manifest in radiant human flesh

our bodies whirling through cosmos, the kiss of heartbeats

the subtle cognizance of hand for hand, and tongue for tongue

the warm moist fabric of the body opening into star-shot rose

flowers

the dewy cock effulgent as it bursts the star

sweet cunt-mouth of world serpent Ouroboros girding the

universe

as it takes its own eternal cock, and cock and cunt united

join the circle

moving through realms of flesh made fantasy and fantasy made

flesh

love as a force that melts the skin so that our bodies join

one cell at a time

until there is nothing left but the radiant universe

the meteors of light flaming through wordless skies

until there is nothing left but the smell of love

but the taste of love, but the fact of love

until love lies dreaming in the crotch of god. . . .

. . .

Nikki Giovanni (born 1943)

Seduction

.

one day

you gonna walk in this house

and i’m gonna have a long African

gown

you’ll sit down and say “The Black…”

and i’m gonna take one arm out

then you – not noticing me at all – wil say “What about this brother…”

and i’m going to be slipping it over my head

and you’ll rap on about “The Revolution…”

while i rest your hand against my stomach

you’ll go on – as you always do – saying

“I just can’t dig…”

while i’m moving your hand up and down

and i’ll be taking your dashiki off

then you’ll say “What we really need…”

and taking your shorts off

the you’ll notice

your state of undress

and knowing you you’ll just say

“Nikki,

isn’t this counterrevolutionary?”

. . .

Olga Broumas (born 1949)

She Loves (1977)

.

Deep prolonged entry with the strong pink cock

the sit-ups it evokes from her, arms fast

on the climbing invisible rope to the sky,

clasping and unclasping the cosmic lorus *

Inside, the long breaths of lung and cunt

swell the vocal cords and a rasp a song

loud sudden overdrive into disintegrate,

spinal melt, video hologram in the belly.

Her tits are luminous and sway to the rhythm

and I grab them and exaggerate their orbs.

Shoulders above like loaves of heaven,

nutmeg-flecked, exuding light like violet diodes

closing circuit where the wall, its fuse box,

so stolidly stood. No room for fantasy.

We watch ourselves transform the past

with such disinterested fascination,

the only attitude that does not stall

the song by an outburst of consciousness

and still lets consciousness, loved and incurable

voyeur, peek in. I tap. I slap. I knee, thump, bellyroll.

Her song is hoarse and is taking me,

incoherent familiar path to that self we are all

cortical cells of. Every o in her body

beelines for her throat, locked on

a rising ski-lift up the mountain, no

grass, no mountaintop, no snow.

White belly folding, muscular as milk.

Pas de deux, pas de chat, spotlight

on the key of G, clef du roman, tour de force letting,

like the sunlight lets a sleeve worn against wind, go.

.

* umbilical cord

. . .

Maxine Kumin (1925-2014)

Together (1970)

.

The water closing

over us and the

going down is all.

Gills are given.

We convert in a

town of broken hulls

and green doubloons.

O you dead pirates

hear us! There is

no salvage. All

you know is the colour

of warm caramel. All

is salt. See how

our eyes have migrated

to the uphill side?

Now we are new round

mouths and no spines

letting the water cover.

It happens over

and over, me in

your body and you

in mine.

. . .

Maxine Kumin

After Love (1970)

.

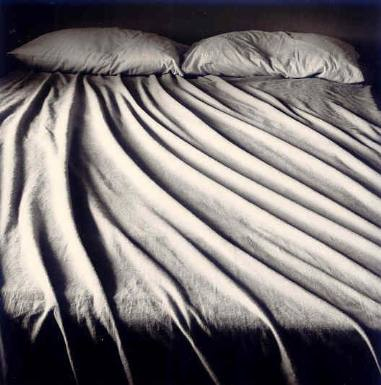

Afterward, the compromise.

Bodies resume their boundaries.

These legs, for instance, mine.

Your arms take you back in.

Spoons of our fingers, lips

admit their ownership.

The bedding yawns, a door

blows aimlessly ajar

and overhead, a plane

singsongs coming down.

Nothing is changed, except

there was a moment when

the wolf, the mongering wolf

who stands outside the self

lay lightly down, and slept.

. . .

Maxine Kumin

Looking back on my Eighty-First Year (2008)

.

How did we get to be old ladies—

my grandmother’s job—when we

were the long-leggèd girls?

— Hilma Wolitzer

.

Instead of marrying the day after graduation,

in spite of freezing on my father’s arm as

here comes the bride struck up,

saying, I’m not sure I want to do this,

I should have taken that fellowship

to the University of Grenoble to examine

the original manuscript

of Stendhal’s unfinished Lucien Leuwen,

I, who had never been west of the Mississippi,

should have crossed the ocean

in third class on the Cunard White Star,

the war just over, the Second World War

when Kilroy was here, that innocent graffito,

two eyes and a nose draped over

a fence line. How could I go?

Passion had locked us together.

Sixty years my lover,

he says he would have waited.

He says he would have sat

where the steamship docked

till the last of the pursers

decamped, and I rushed back

littering the runway with carbon paper . . .

Why didn’t I go? It was fated.

Marriage dizzied us. Hand over hand,

flesh against flesh for the final haul,

we tugged our lifeline through limestone and sand,

lover and long-leggèd girl.

. . .

For more poems click on the following links:

“And Don’t Think I Won’t Be Waiting”: Love poems by Audre Lorde

https://zocalopoets.com/category/poets-poetas/pat-parker/

Pro-Sex Poems of Love and Desire: Herrick and St.Vincent Millay

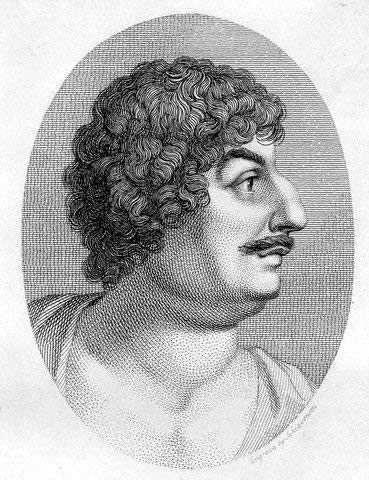

Posted: December 9, 2014 Filed under: Edna St.Vincent Millay, English, Robert Herrick Comments Off on Pro-Sex Poems of Love and Desire: Herrick and St.Vincent MillayRobert Herrick (1591-1674)

Love Lightly Pleased

.

Let fair or foul my mistress be,

Or low, or tall, she pleaseth me;

Or let her walk, or stand, or sit,

The posture her’s, I’m pleased with it;

Or let her tongue be still, or stir

Graceful is every thing from her;

Or let her grant, or else deny,

My love will fit each history.

. . .

Delight in Disorder

.

A sweet disorder in the dress

Kindles in clothes a wantonness;

A lawn about the shoulders thrown

Into a fine distraction;

An erring lace, which here and there

Enthrals the crimson stomacher;

A cuff neglectful, and thereby

Ribbons to flow confusedly;

A winning wave, deserving note,

In the tempestuous petticoat;

A careless shoe-string, in whose tie

I see a wild civility;–

Do more bewitch me, than when art

Is too precise in every part.

. . .

Upon the Nipples of Julia’s Breast

.

Have ye beheld (with much delight)

A red rose peeping through a white?

Or else a cherry (double graced)

Within a lily? Centre placed?

Or ever marked the pretty beam

A strawberry shows half drowned in cream?

Or seen rich rubies blushing through

A pure smooth pearl, and orient too?

So like to this, nay all the rest,

Is each neat niplet of her breast.

. . .

A Hymn to Love

.

I will confess

With cheerfulness,

Love is a thing so likes me,

That, let her lay

On me all day,

I’ll kiss the hand that strikes me.

.

I will not, I,

Now blubb’ring cry,

It, ah! too late repents me

That I did fall

To love at all–

Since love so much contents me.

.

No, no, I’ll be

In fetters free;

While others they sit wringing

Their hands for pain,

I’ll entertain

The wounds of love with singing.

.

With flowers and wine,

And cakes divine,

To strike me I will tempt thee;

Which done, no more

I’ll come before

Thee and thine altars empty.

Edna St.Vincent Millay (1892-1950)

I, being born a woman and distressed (1923)

.

I, being born a woman and distressed

By all the needs and notions of my kind,

Am urged by your propinquity to find

Your person fair, and feel a certain zest

To bear your body’s weight upon my breast:

So subtly is the fume of life designed,

To clarify the pulse and cloud the mind,

And leave me once again undone, possessed.

Think not for this, however, the poor treason

Of my stout blood against my staggering brain,

I shall remember you with love, or season

My scorn with pity, — let me make it plain:

I find this frenzy insufficient reason

For conversation when we meet again.

. . .

What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why (1923)

.

What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why,

I have forgotten, and what arms have lain

Under my head till morning; but the rain

Is full of ghosts tonight, that tap and sigh

Upon the glass and listen for reply,

And in my heart there stirs a quiet pain

For unremembered lads that not again

Will turn to me at midnight with a cry.

Thus in the winter stands the lonely tree,

Nor knows what birds have vanished one by one,

Yet knows its boughs more silent than before:

I cannot say what loves have come and gone,

I only know that summer sang in me

A little while, that in me sings no more.

. . .

I, too, beneath your moon, Almighty Sex (1939)

.

I too beneath your moon, almighty Sex,

Go forth at nightfall crying like a cat,

Leaving the lofty tower I laboured at

For birds to foul and boys and girls to vex

With tittering chalk; and you, and the long necks

Of neighbours sitting where their mothers sat

Are well aware of shadowy this and that

In me, that’s neither noble nor complex.

Such as I am, however, I have brought

To what it is, this tower; it is my own;

Though it was reared To Beauty, it was wrought

From what I had to build with: honest bone

Is there, and anguish; pride; and burning thought;

And lust is there, and nights not spent alone.

. . . . .

Pro-Sex Poems of Love and Desire: the exquisite verse of Constantine P. Cavafy

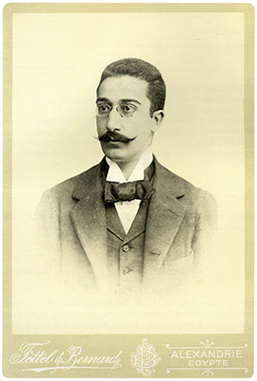

Posted: December 5, 2014 Filed under: English, Greek, Konstantin Kavafis Comments Off on Pro-Sex Poems of Love and Desire: the exquisite verse of Constantine P. CavafyC.P. Cavafy (Greek poet from Alexandria, Egypt: 1863-1933)

Body, Remember

.

Body, remember not only how much you were loved,

not only the beds you lay on,

but also those desires that glowed openly

in eyes that looked at you,

trembled for you in the voices—

only some chance obstacle frustrated them.

Now that it’s all finally in the past,

it seems almost as if you gave yourself

to those desires too—how they glowed,

remember, in eyes that looked at you,

remember, body, how they trembled for you in those voices.

.

Body, Remember – in the original Greek:

Θυμήσου, Σώμα…

.

Σώμα, θυμήσου όχι μόνο το πόσο αγαπήθηκες,

όχι μονάχα τα κρεββάτια όπου πλάγιασες,

αλλά κ’ εκείνες τες επιθυμίες που για σένα

γυάλιζαν μες στα μάτια φανερά,

κ’ ετρέμανε μες στην φωνή — και κάποιο

τυχαίον εμπόδιο τες ματαίωσε.

Τώρα που είναι όλα πια μέσα στο παρελθόν,

μοιάζει σχεδόν και στες επιθυμίες

εκείνες σαν να δόθηκες — πώς γυάλιζαν,

θυμήσου, μες στα μάτια που σε κύτταζαν·

πώς έτρεμαν μες στην φωνή, για σε, θυμήσου, σώμα.

. . .

He had come there to read…

.

He had come there to read. Two or three books lie open,

books by historians, by poets.

But he read for barely ten minutes,

then gave it up, falling half asleep on the sofa.

He’s completely devoted to books—

but he’s twenty-three, and very good-looking;

and this afternoon Eros entered

his ideal flesh, his lips.

An erotic warmth entered

his completely lovely flesh—

with no ridiculous shame about the form the pleasure took….

.

In the original Greek:

Ήλθε για να διαβάσει —

.

Ήλθε για να διαβάσει. Είν’ ανοιχτά

δυο, τρία βιβλία· ιστορικοί και ποιηταί.

Μα μόλις διάβασε δέκα λεπτά,

και τα παραίτησε. Στον καναπέ

μισοκοιμάται. Aνήκει πλήρως στα βιβλία —

αλλ’ είναι είκοσι τριώ ετών, κ’ είν’ έμορφος πολύ·

και σήμερα το απόγευμα πέρασ’ ο έρως

στην ιδεώδη σάρκα του, στα χείλη.

Στη σάρκα του που είναι όλο καλλονή

η θέρμη πέρασεν η ερωτική·

χωρίς αστείαν αιδώ για την μορφή της απολαύσεως …..

. . .

He asked about the quality

.

He left the office where he’d taken up

a trivial, poorly paid job

(eight pounds a month, including bonuses)—

left at the end of the dreary work

that kept him bent all afternoon,

came out at seven and walked off slowly,

idling his way down the street. Good-looking;

and interesting: showing as he did that he’d reached

his full sensual capacity.

He’d turned twenty-nine the month before.

He idled his way down the main street

and the poor side-streets that led to his home.

Passing in front of a small shop

that sold cheap and flimsy things for workers,

he saw a face inside there, saw a figure

that compelled him to go in, and he pretended

he wanted to look at some colored handkerchiefs.

He asked about the quality of the handkerchiefs

and how much they cost, his voice choking,

almost silenced by desire.

And the answers came back the same way,

distracted, the voice hushed,

offering hidden consent.

They kept on talking about the merchandise—but

the only purpose: that their hands might touch

over the handkerchiefs, that their faces, their lips,

might move close together as though by chance—

a moment’s meeting of limb against limb.

Quickly, secretly, so the shopowner sitting at the back

wouldn’t realize what was going on.

.

Ρωτούσε για την ποιότητα—

.

Aπ’ το γραφείον όπου είχε προσληφθεί

σε θέσι ασήμαντη και φθηνοπληρωμένη

(ώς οκτώ λίρες το μηνιάτικό του: με τα τυχερά)

βγήκε σαν τέλεψεν η έρημη δουλειά

που όλο το απόγευμα ήταν σκυμένος:

βγήκεν η ώρα επτά, και περπατούσε αργά

και χάζευε στον δρόμο.— Έμορφος·

κ’ ενδιαφέρων: έτσι που έδειχνε φθασμένος

στην πλήρη του αισθησιακήν απόδοσι.

Τα είκοσι εννιά, τον περασμένο μήνα τα είχε κλείσει.

Εχάζευε στον δρόμο, και στες πτωχικές

παρόδους που οδηγούσαν προς την κατοικία του.

Περνώντας εμπρός σ’ ένα μαγαζί μικρό

όπου πουλιούνταν κάτι πράγματα

ψεύτικα και φθηνά για εργατικούς,

είδ’ εκεί μέσα ένα πρόσωπο, είδε μια μορφή

όπου τον έσπρωξαν και εισήλθε, και ζητούσε

τάχα να δει χρωματιστά μαντήλια.

Pωτούσε για την ποιότητα των μαντηλιών

και τι κοστίζουν με φωνή πνιγμένη,

σχεδόν σβυσμένη απ’ την επιθυμία.

Κι ανάλογα ήλθαν η απαντήσεις,

αφηρημένες, με φωνή χαμηλωμένη,

με υπολανθάνουσα συναίνεσι.

Όλο και κάτι έλεγαν για την πραγμάτεια — αλλά

μόνος σκοπός: τα χέρια των ν’ αγγίζουν

επάνω απ’ τα μαντήλια· να πλησιάζουν

τα πρόσωπα, τα χείλη σαν τυχαίως·

μια στιγμιαία στα μέλη επαφή.

Γρήγορα και κρυφά, για να μη νοιώσει

ο καταστηματάρχης που στο βάθος κάθονταν.

. . .

Days of 1896

.

He became completely degraded. His erotic tendency,

condemned and strictly forbidden

(but innate for all that), was the cause of it:

society was totally prudish.

He gradually lost what little money he had,

then his social standing, then his reputation.

Nearly thirty, he had never worked a full year—

at least not at a legitimate job.

Sometimes he earned enough to get by

acting the go-between in deals considered shameful.

He ended up the type likely to compromise you thoroughly

if you were seen around with him often.

But this isn’t the whole story—that would not be fair.

The memory of his beauty deserves better.

There is another angle; seen from that

he appears attractive, appears

a simple, genuine child of love,

without hesitation putting,

above his honor and reputation,

the pure sensuality of his pure flesh.

Above his reputation? But society,

prudish and stupid, had it wrong.

.

Μέρες του 1896

.

Εξευτελίσθη πλήρως. Μια ερωτική ροπή του

λίαν απαγορευμένη και περιφρονημένη

(έμφυτη μολοντούτο) υπήρξεν η αιτία:

ήταν η κοινωνία σεμνότυφη πολύ.

Έχασε βαθμηδόν το λιγοστό του χρήμα·

κατόπι τη σειρά, και την υπόληψί του.

Πλησίαζε τα τριάντα χωρίς ποτέ έναν χρόνο

να βγάλει σε δουλειά, τουλάχιστον γνωστή.

Ενίοτε τα έξοδά του τα κέρδιζεν από

μεσολαβήσεις που θεωρούνται ντροπιασμένες.

Κατήντησ’ ένας τύπος που αν σ’ έβλεπαν μαζύ του

συχνά, ήταν πιθανόν μεγάλως να εκτεθείς.

Aλλ’ όχι μόνον τούτα. Δεν θάτανε σωστό.

Aξίζει παραπάνω της εμορφιάς του η μνήμη.

Μια άποψις άλλη υπάρχει που αν ιδωθεί από αυτήν

φαντάζει, συμπαθής· φαντάζει, απλό και γνήσιο

του έρωτος παιδί, που άνω απ’ την τιμή,

και την υπόληψί του έθεσε ανεξετάστως

της καθαρής σαρκός του την καθαρή ηδονή.

Aπ’ την υπόληψί του; Μα η κοινωνία που ήταν

σεμνότυφη πολύ συσχέτιζε κουτά.

. . .

Comes to rest

.

It must have been one o’clock at night

or half past one.

A corner in the wine-shop

behind the wooden partition:

except for the two of us the place completely empty.

An oil lamp barely gave it light.

The waiter, on duty all day, was sleeping by the door.

No one could see us. But anyway,

we were already so aroused

we’d become incapable of caution.

Our clothes half opened—we weren’t wearing much:

a divine July was ablaze.

Delight of flesh between

those half-opened clothes;

quick baring of flesh—the vision of it

that has crossed twenty-six years

and comes to rest now in this poetry.

.

Να μείνει

.

Η ώρα μια την νύχτα θάτανε,

ή μιάμισυ.

Σε μια γωνιά του καπηλειού·

πίσω απ’ το ξύλινο το χώρισμα.

Εκτός ημών των δυο το μαγαζί όλως διόλου άδειο.

Μια λάμπα πετρελαίου μόλις το φώτιζε.

Κοιμούντανε, στην πόρτα, ο αγρυπνισμένος υπηρέτης.

Δεν θα μας έβλεπε κανείς. Μα κιόλας

είχαμεν εξαφθεί τόσο πολύ,

που γίναμε ακατάλληλοι για προφυλάξεις.

Τα ενδύματα μισοανοίχθηκαν — πολλά δεν ήσαν

γιατί επύρωνε θείος Ιούλιος μήνας.

Σάρκας απόλαυσις ανάμεσα

στα μισοανοιγμένα ενδύματα·

γρήγορο σάρκας γύμνωμα — που το ίνδαλμά του

είκοσι έξι χρόνους διάβηκε· και τώρα ήλθε

να μείνει μες στην ποίησιν αυτή.

. . .

One night

.

The room was cheap and sordid,

hidden above the suspect taverna.

From the window you could see the alley,

dirty and narrow. From below

came the voices of workmen

playing cards, enjoying themselves.

And there on that common, humble bed

I had love’s body, had those intoxicating lips,

red and sensual,

red lips of such intoxication

that now as I write, after so many years,

in my lonely house, I’m drunk with passion again.

.

Μια Νύχτα

.

Η κάμαρα ήταν πτωχική και πρόστυχη,

κρυμένη επάνω από την ύποπτη ταβέρνα.

Aπ’ το παράθυρο φαίνονταν το σοκάκι,

το ακάθαρτο και το στενό. Aπό κάτω

ήρχονταν η φωνές κάτι εργατών

που έπαιζαν χαρτιά και που γλεντούσαν.

Κ’ εκεί στο λαϊκό, το ταπεινό κρεββάτι

είχα το σώμα του έρωτος, είχα τα χείλη

τα ηδονικά και ρόδινα της μέθης —

τα ρόδινα μιας τέτοιας μέθης, που και τώρα

που γράφω, έπειτ’ από τόσα χρόνια!,

μες στο μονήρες σπίτι μου, μεθώ ξανά.

. . .

When they come alive

.

Try to keep them, poet,

those erotic visions of yours,

however few of them there are that can be stilled.

Put them, half-hidden, in your lines.

Try to hold them, poet,

when they come alive in your mind

at night or in the brightness of noon.

.

Όταν Διεγείρονται

.

Προσπάθησε να τα φυλάξεις, ποιητή,

όσο κι αν είναι λίγα αυτά που σταματιούνται.

Του ερωτισμού σου τα οράματα.

Βάλ’ τα, μισοκρυμένα, μες στες φράσεις σου.

Προσπάθησε να τα κρατήσεις, ποιητή,

όταν διεγείρονται μες στο μυαλό σου,

την νύχτα ή μες στην λάμψι του μεσημεριού.

. . . . .

All of the above poems:

from: C.P. Cavafy, Collected Poems. Translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard. Edited by George Savidis. Revised Edition. Princeton University Press, 1992

. . . . .

Pro-Sex Poems of Love and Desire: Brainard, Shepherd, Smith, Liu and Teare

Posted: December 2, 2014 Filed under: English, Joe Brainard, Reginald Shepherd Comments Off on Pro-Sex Poems of Love and Desire: Brainard, Shepherd, Smith, Liu and TeareJoe Brainard (Arkansas/Oklahoma/New York City, 1942-1994)

Sex (written in 1969)

.

I like sex best when it’s fast and fun. Or slow and beautiful. Beautiful, of course can be fun too. And fun, beautiful. I like warm necks. And the smalls of backs. I’m not sure if that’s the right word: small. What I mean is the part of the back that goes in the most. Just before your bottom comes out. I like navels. I like under-arms. I don’t care for feet especially, or legs. I like faces. Eyes and lips and ears. I think that what I like most about sex is just touching. Skin is so alive. I like cold clean sheets. I like breasts and nipples. What I’m a sucker for most is a round full bottom. I really don’t like that word bottom. I think underwear is sexy. I like hair on heads, but hair on the body I can take it or leave it. Skinny builds don’t turn me on as much as normal builds. Probably because I’m skinny myself. I have a weak spot for blonds. I like to fuck sometimes but I don’t like to be fucked. What I really like is just a good plain blow-job. It’s rhythm that makes me come the best. I don’t think that, in bed, I take a masculine role or a feminine role. I guess I must be somewhere in between, or both. Sex-wise I’m not very adventurous. I am sure that there are a lot of things I like that I don’t know I like yet. I hope so. So—now you have some idea of what I like in bed.

. . .

Part of the so-called “New York School” of artists, dancers, musicians and poets, Joe Brainard died of AIDS-induced pneumonia in 1994.

Reginald Shepherd (1963-2008), a gay, African-American poet, wrote the following commentary in February 2008:

“[At a recent poetry conference poet Randall Mann asked] a provocative question about why so many contemporary gay male poets avoid writing about sex…..a question I’ve asked myself about my own work, which is full of desire – but not much actual sex. I replied that for a lot of socially and financially comfortable gay men, they are born insiders and then this thing happens to them that pushes them from the centre to the margins, and they then spend a great deal of energy trying to get back home to the centre by asserting how safe and normal and respectable they are, with their good taste and their well-groomed dogs, and how they just want to be like everybody else – which most of them are, except for the alcoholism and the crystal meth addictions – (sorry, bitchy comment). I remember someone at a meeting of the mostly undergraduate gay student group during my brief sojourn as a PhD student at Harvard saying that gays weren’t any more artistic and sensitive than anyone else. I responded, ‘Yes, and that’s the problem.’

Gays may have inalienable rights which they insist on – good luck with that. But one thing they apparently don’t have anymore…is Sex, since fucking, blowjobs, rimjobs, and even handjobs, are what disgusts straights to have to think about…..

I’d like to marry my partner (if only to have access to his health insurance, which I sure need, what with my HIV and my chemotherapy, and my slew of other medical problems). I’d like to have a kid (kids in the plural would be too much to handle). I’d even like a dog, though we’d have to fix the back fences first. But I am definitely not like everybody else, nor do I wish to be. As Alan Parsons Project sang, “I wouldn’t wanna be like you.” I’m not even like all the other boys!”

. . .

Reginald Shepherd (Bronx, New York, 1963-2008)

Under the Milky Way

.

Some stars, brightest early, falter

and fade, while some increase in magnitude

throughout the night. Sometimes

fistfuls of scattered light croon

through my star-spattered sleep; sometimes

the stars are silent. Sometimes the soul loses control

of Plato’s horses swimming viscous air: the sensual,

the beauty merely intellectual. Sometimes

not. Some nights I can see Gemini,

white shadows Gemini leaves. I’m lying

with my hands here in my pants, hard

for you but to no end. I’m rummaging

this rumpled bed where we last fucked

looking for clues to you, a print

of dried semen or an invisible “I love you”

in Vaseline. I wanted to take your picture

as you lay spread open, white briefs bunched at

your ankles, but what can cameras

keep? Your portrait’s burned into my retina

upside-down. Buoyed above the tedium

of the working week’s routine, sometimes

obscured by clouds, it’s a glittering prize

for the swiftest, the fairest, well hung

in the desiring sky. Your body,

I mean. I think of your body

as a museum of careless gestures:

the way you light a cigarette or turn

a sticking doorknob, the way you shake your head

at something you’ve just read. Impulses

chase themselves through a closed circuit,

the expenditure of energy unavailable for work:

I call it desire, or just unsated hunger.

Your body is too far above me to read

by its light: I walked right into two blue eyes

and drowned myself, can’t remember

if you pulled me out. Here I am

washed ashore, your summer skin

sees right through me. I’m leading myself

by the hand again somewhere I’ve been

too many times, I’m floating on mercury

toward you in a tissue-paper boat and you’re

looking away. Here I come.

. . .

Shepherd then goes on to quote poet Aaron Smith:

“Recently at a gay publishing party a friend told me that he wants his new book to be about something other than cock because that’s all that gay men write about. While everyone around him nodded in agreement, I was thinking: Can you please tell me which poets are currently writing about cock? Because those are the poets I want to read! I couldn’t help but sense an undercurrent of conservatism in his statement – as if gay sex has no place in the pristine rooms of contemporary poetry, a sense that we have already done that. I wonder—this early in the 21st century—is there really nothing else we can say about the gay erotic?…..And I caution poets against listening to the voices that say we’ve heard enough about sex (or about discrimination or about “coming out” or about AIDS)…”

. . .

Aaron Smith

Boston

.

I’ve been meaning to tell

you how the sky is pink

here sometimes like the roof

of a mouth that’s about to chomp

down on the crooked steel teeth

of the city,

I remember the desperate

things we did

and that I stumble

down sidewalks listening

to the buzz of street lamps

at dusk and the crush

of leaves on the pavement,

Without you here I’m viciously lonely

and I can’t remember

the last time I felt holy,

the last time I offered

myself as sanctuary

.

I watched two men

press hard into

each other, their bodies

caught in the club’s

bass drum swell,

and I couldn’t remember

when I knew I’d never

be beautiful, but it must

have been quick

and subtle, the way

the holy ghost can pass

in and out of a room.

I want so desperately

to be finished with desire,

the rushing wind, the still

small voice.

. . .

From Blue on Blue Ground © 2005 Aaron Smith

. . .

Aaron Smith

The Bar Closes (But You Don’t Want to Go Home)

.

While the man you love bites stories

into someone else’s back, there’s a flicker

in your eye only seen in late-night

.

television (the heroine stretching her face, half-

grin, half-cry), all you’ve done wrong

clarified in a liquidy theme song.

.

You say, the only party is my party, the only

death worth dying is the disastrous one.

If everything was black and white,

darling, the world would look more

like an afterlife, certain and grand

and unexplainable. But even the shoreline

against the city tonight is indecisive,

jagged and rocky the way desire used to be

before you knew enough to know it was desire.

. . .

Aaron Smith is the poetry editor for Bloom Literary Journal (“Queer Fiction, Art, Poetry & More”).

. . .

Timothy Liu (born 1965, San José, California)

Almost There

.

Hard to imagine getting

anywhere near another semi-

nude encounter down this concrete

slab of interstate, the two of us

all thumbs—

white-throated swifts mating mid-flight

instead of buckets of

crispy wings thrown down

hoi polloi—

an army of mouths

eager to feed

left without any lasting sustenance.

Best get down on all fours.

Ease our noses past

rear-end collisions wrapped around

guardrails shaking loose their bolts

while unseen choirs jacked on

airwaves go on preaching

loud and clear to every

last pair of unrepentant ears—

.

(2011)

. . .

Timothy Liu

Holding Pattern

.

Intermittent wet under

cloud cover, dry

where you are. All day

this rain without

you—so many planes

above the cloud line

carrying strangers

either closer or

farther away from

one another while

you and I remain

grounded. Are we

moving anyway

towards something

finer than what the day

might bring or is this

an illusion, a stay

against everything

unforeseen—tiny bottles

clinking as the carts

make their way down

the narrow aisle

no matter what

class we find ourselves

seated in, your voice

the captain’s voice

even if the masks

do not inflate

and there’s no one

here to help me

put mine on first—

my head cradled

between your knees.

.

(2014)

. . .

Timothy Liu

Hard Evidence

.

A room walled-in by books where the hours withdraw.

At the foot of an unmade bed a bird of paradise.

Motel carpet melted where an iron had been.

His attention anchored to a late night “glory hole”.

Of janitorial carts no heaviness like theirs.

Desire seen cavorting with the yes inside the no.

A soul kiss swimming solo in an open wound.

The self as church where the whores now gather in.

.

(1999)

. . .

Timothy Liu is an American poet and the editor of Word of Mouth: An Anthology of Gay American Poetry. A graduate of Brigham Young University and the University of Houston, Liu is a Professor of English at William Paterson University in Wayne, New Jersey. His journals and papers are in the Berg Collection archives of the New York City Public Library.

. . .

Brian Teare (born 1974, Tuscaloosa, Alabama)

Eden Incunabulum

.

“As his unlikeness fitted mine”—

so his luciferous kiss, ecliptic : me pinned beneath lips bitten as under weight of prayer, Ave—but no common vocative, no paradise above, and we not beholden to a name, not to a local god banking fever blaze his seasonal malady of flowers—nor to demi-urge nor the lapsarian system’s glittering, how later we spoke between us of sacred and profane as if the numinous could bring death—the only system—to bear burn outside him and hang its glister wisdom and singe in the viridian wilt. Lilt, to break salt in that sugar where skin was no choice and sanguine, not blameless, though, Ave, I loved our words for want beginning liquor, squander sip and fizz : fuck, ferment I loved and bluebottles tippling windfall rot, bruises’ wicked wine gone vinegar beneath the taut brief glaze of wings, but it was not yet nameable, what we later called disease : script brought us by the trick snake’s fakey Beelzebubbery. In the dirt with his dictionary skin, tight skein of syllables knit by un- numbered undulating clicking ribs, the snake slunk and stung and spelled the dust with his tongue and tail and was nothing, a black forked lisp in the subfusc grass hued blue as the blue sky tipped its lip to ocean horizon and filled, hugest amphora, and sank, evening, Ave, I will tell you now I loved it all. That in his hot body there was something similar to the idea of heat which was in my mind, that when we alembic, lay together, we bequeathed the white fixed earth beneath ardent water and a season’s kept blood, and I not a rib of his, not further hurt in his marrow—for the idea of death was in him, the only system—and we lay together in the field that was not yet page, not begun with A—, not alpha nor apple, not Ave, not yet because what we knew was the least of it then. It was difficult to sleep with the love of words gone gospel between my thighs where nightly he’d jack the pulpit, Ave Corpus, Ave Numen, gnosis and throb unalphabetical, I will tell you I loved it all, fastest brushfires and dryburns his body’s doublecross, garden lost to loss, incurable season : wilt, lilt : singe, our song. And the snake, lumen skin of alphabets, rubbing his stomach in the dust until his tin eyes filled with milk, his slack skin flickered and split and new black sinew out of the slough dead lettered vellum legless crept and let fall wept whisper, hiss, paperhush : with the skin language left behind I bind time to memorial : Book of Our Garden Hours, illuminated bloom : Here a gilt script singe sings of heat split in its leaves, and the bee gives suck to the book : Ave Incunabulum, love’s first work : Ave, In Memoriam— [ J—05/1999 ]

.

Incunabulum: a book printed at an early date (esp. before 1501)

“As his unlikeness fitted mine”—from Tennyson’s In Memoriam

. . . . .

Jane Kenyon: Poemas sobre el Invierno

Posted: November 25, 2014 Filed under: English, Jane Kenyon, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Jane Kenyon: Poemas sobre el InviernoJane Kenyon (1947-1995)

Poemas sobre el Invierno / Poems about Winter

. . .

Indolencia durante un invierno temprano

.

Llega una carta de unos amigos –

¡Déjenlos divorciarse, todos,

pues casarse de nuevo y volver a divorciarse!

Perdóname si me quede frito…

.

Yo debería avivar el fogón de leña,

ojalá que lo había hecho la hora pasada.

La casa se volverá frío como la piedra.

¡Fabuloso – no tendrá que hacer el balance con mi chequera!

.

Hay un amontonamiento precario de correo sin respuesta

y el gato lo derrumba cuando viene por verme.

.

Y quedo aquí, en mi silla,

enterrado bajo los escombros

de matrimonios fallidos,

formularios para renovar suscripciones de revistas,

cuentas,

amistades caducadas…

.

Es el sol que provoca esta clase de consideración.

Parte del cielo más y más temprano cada día, y se va en algún lugar,

como un marido preocupado,

o como una esposa melancólica.

. . .

Indolence in early winter

.

A letter arrives from friends…

Let them all divorce, remarry

and divorce again!

Forgive me if I doze off in my chair.

.

I should have stoked the stove

an hour ago. The house

will go cold as stone. Wonderful!

I won’t have to go on

balancing my chequebook.

.

Unanswered mail piles up

in drifts, precarious,

and the cat sets everything sliding

when she comes to see me.

.

I am still here in my chair,

buried under the rubble

of failed marriages, magazine

subscription renewal forms, bills,

lapsed friendships…

.

This kind of thinking is caused

by the sun. It leaves the sky earlier

every day, and goes off somewhere,

like a troubled husband,

or like a melancholy wife.

. . .

Mientras estuvimos discutiendo

.

Cayó la primera nieve – o debería decir:

Voló oblicuamente y parecía como

la casa se movía descuidadamente por el espacio.

.

Las lágrimas salpicaron como abalorios en tu pulóver.

Pues, para unos largos momentos, no hablaste.

Ningún placer en las tazas de té que hice distraídamente a las cuatro.

.

El cielo se oscureció. Oí el arribo del periódico y salí.

La luna oteaba entre nubes disintegrandos.

Dije en voz alta:

“Mira, hemos hecho daño.”

. . .

While we were arguing

.

The first snow fell – or should I say

it flew slantwise, so it seemed

to be the house

that moved so heedlessly through space.

.

Tears splashed and beaded on your sweater.

Then for long moments you did not speak.

No pleasure in the cups of tea I made

distractedly at four.

.

The sky grew dark. I heard the paper come

and went out. The moon looked down

between disintegrating clouds. I said

aloud: “You see, we have done harm.”

. . .

La nieve y una mañana oscura

.

Cae sobre el topillo del campo que empujar con el hocico

en alguna parte de las malas hierbas;

cae en el ojo abierto del estanque.

Y hace venir tarde el correo.

.

El trepador hace espirales de frente/abajo en el árbol.

.

Estoy adormilada y benigna en la oscuridad.

No hay nada que quiero…

. . .

Dark morning: Snow

.

It falls on the vole, nosing somewhere

through weeds, and on the open

eye of the pond. It makes the mail

come late.

.

The nuthatch spirals head first

down the tree.

.

I’m sleepy and benign in the dark.

There’s nothing I want…

. . .

Invierno seco

.

Tan poco de nieve…

La hierba del campo es como

un pensamiento terrible que

nunca desapareció completamente…

. . .

Dry winter

.

So little snow that the grass in the field

like a terrible thought

has never entirely disappeared…

. . . . .

Jane Kenyon: poemas íntimos sobre un esposo

Posted: November 20, 2014 Filed under: English, Jane Kenyon, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Jane Kenyon: poemas íntimos sobre un esposoJane Kenyon (1947-1995, poeta/traductor estadounidense)

. . .

The First Eight Days of the Beard

.

1. A page of exclamation points

2. A class of cadets at attention

3. A school of eels

4. Standing commuters

5. A bed of nails for the swami

6. Flagpoles of unknown countries

7. Centipedes resting on their laurels

8. The toenails of the face

. . .

Los Primeros Días de la Barba Incipiente

.

1. Una página de puntos de exclamación

.

2. Una clase de cadetes en posición de firmes

.

3. Una escuela de anguilas

.

4. Viajeros suburbanos en pie en la tren

.

5. Un lecho de clavos para un swami

.

6. Mástiles de paises desconocidos

.

7. Ciempieses descansando en sus laureles

.

8. Las uñas del pie de la cara

. . .

The Socks

.

While you were away

I matched your socks

and rolled them into balls.

Then I filled your drawer with

tight dark fists.

. . .

Los Calcetines

.

Mientras estabas fuera

emparejé tus calcetines

y los rodé en pelotas.

Pues llené tu cajón con

puños morenos apretados.

. . .

The Shirt

.

The shirt touches his neck

and smooths over his back.

It slides down his sides.

It even goes down below his belt

– down into his pants.

Lucky shirt.

. . .

La Camisa

.

La camisa toca su cuello

y alisa sobre su espalda.

Se desliza sus costados,

aun descende abajo de la cintura

– dentro de sus pantalones.

¡Qué camisa afortunada!

. . .

Alone for a week

.

I washed a load of clothes

and hung them out to dry.

Then I went up to town

and busied myself all day.

The sleeve of your best shirt

rose ceremonious

when I drove in; our night-

clothes twined and untwined in

a little gust of wind.

.