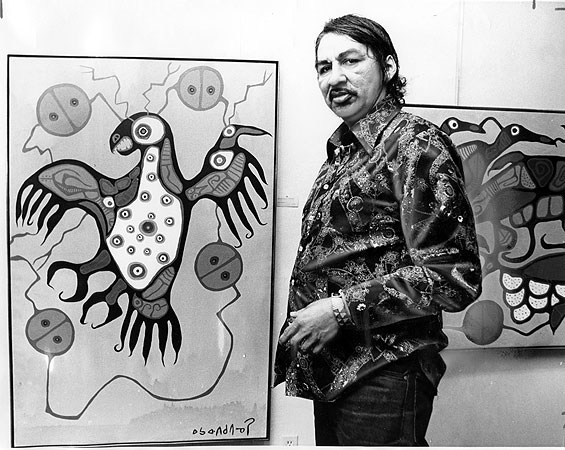

Norval Morrisseau – Shaman-Artist: Armand Garnet Ruffo’s “Man Changing into Thunderbird (Transmigration), 1977”

Posted: October 14, 2013 Filed under: Armand Garnet Ruffo, English | Tags: Norval Morrisseau Comments Off on Norval Morrisseau – Shaman-Artist: Armand Garnet Ruffo’s “Man Changing into Thunderbird (Transmigration), 1977”ZP_Norval Morrisseau_Man Changing into Thunderbird_1977_panel 1 of 6

.

“I am a Shaman-Artist. My paintings are icons. That is to say: they are images which help focus on spiritual powers generated by traditional beliefs and wisdom.” (Norval Morrisseau)

.

In the course of writing Man Changing Into Thunderbird, a book about the life of the acclaimed Ojibway artist Norval Morrisseau, I found that his art moved me in such a manner that a natural and spontaneous response to it was to write poetry. Initially, I thought that I would write a few ekphrastic poems based on some of the paintings that I admired most and I thought gave insight into the artist. And because the poems are based on specific paintings, which for the most part are dated, I also figured that the inclusion of the poems would provide a time frame that would help ground potential readers. However, as I learned more about Morrisseau’s life and immersed myself in the paintings, more poems appeared. What did these paintings mean to him, and what do they mean to us, the viewers? My plan was to include all the poems in the one book, but as the poems increased I realized that due to length there were far too many to include them all. I also realized that I had a complete book of poetry. The Thunderbird Poems includes all the poems that I wrote during this period of study and contemplation on the art of Norval Morrisseau. The piece below, “Man Changing Into Thunderbird (Transmigration), 1977”, is excerpted from The Thunderbird Poems.

.

Armand Garnet Ruffo

. . .

Norval Morrisseau said that for the longest time he dreamed of doing something great. In 1976 he joins the Eckankar “new age” movement in an attempt to stop drinking, and moves to Winnipeg. While there he plunges into a six panel painting with complete confidence that speaks to his genius.

Man Changing Into Thunderbird (Transmigration), 1977

Though he has had no idea how to squeeze the essence of the story onto canvas from the first time he hears it he wants to paint it. But how to go about it? The question haunts him, dangles in front of him, gets caught in the dream-catcher web of a spider, escapes through a hole in the night sky and slides down a path of owl feathers into the world of myth and creation.

.

The story says there were seven brothers. One day

the youngest Wahbi Ahmik

went hunting and met a beautiful woman

named Nimkey Banasik.

They fell in love at first sight

and the young warrior took her home to his wigwam

where they lived as man and wife

and were happy.

All the brothers cherished her except one

Ahsin, the oldest,

Who felt only hatred for her.

.

The idea grows inside him the way a butterfly grows inside a chrysalis. Except it is not about a butterfly, it is about a thunderbird and, more, about a whole way of being, about perception and belief. When it finally cracks open, or rather he cracks it open, the idea is so large he knows instinctively it will be one of his most important paintings. Not junk commercialism done for a quick buck. Not twenty paintings pinned to a clothesline, jumping between them like a jackrabbit. Not another set of nesting loons or another multi-coloured trout. Not something he can paint in a half-closed eyelid stupor. This time his eyes are wide open and burning with possibility as though giant talons were digging into his memory and stirring imagination. As though they were clamped onto his shoulder muscles with the steady beat of locomotive wings and were lifting him high above the ground.

.

One day Wahbi Ahmik returned from hunting

and discovered the campfire near his wigwam

stained in blood.

Panic stricken he rushed to his wife

but discovered her gone.

Knowing what his brother Ahsin felt for her

he stormed into his tent

And demanded to know what had happened.

I see a trail of blood leading into the forest.

What have you done?

.

By this time he is again showing at Pollock Gallery in Toronto but hardly under Jack Pollock’s tutelage, their relationship strained by their personalities. His home in Red Lake is now far behind him, and he is lapping up the good life like a saucer of cream. Though it isn’t cream he is drinking. By this time his art little more than a means to an end, more commerce than calling. He will sell it to buy the basics like cigarettes and groceries (though he eats little for a man his size), shoes or a shirt when he needs it. Though more often than not he simply trades for whatever he wants: a week’s rent in a flop house, a bottle, a meal, an English Derby plate, a Spode teapot, a blowjob, a fuck, everything and anything. The moment: the only thing that matters.

.

Ahsin was not afraid of his younger brother’s anger.

You brought this woman Nimkey Banasik to our village.

We were all happy together before she came.

Now she is gone for good.

When you left this morning I sent our other brothers away

to be alone with her.

Then I saw her cooking for you

and I got out my sharpest arrow

which found its mark in her hip.

I would have chased her down and killed her

if not for the roar of thunder

that filled the sky

and frightened me.

.

As for Pollock he is still smarting from the Kenora court case a couple of years earlier when he was sued for stealing several of Morrisseau’s paintings. (Though he knows it wasn’t instigated by the artist himself, and after it was over Morrisseau gave him a big bear hug like he was cheering for Pollock all along.) Furthermore, by this time Pollock’s gallery and personal life are in shambles, his blatant honesty and vanity making him persona non-gratis in what he calls Toronto’s bitchy art scene. His own life of flirting with excess, his hot and horny appetite for cocaine and sex scarring his body and mind. (So honest and vain Pollock admits it all in a book printed in England where nobody knows him personally, admits that if he were to drop dead tomorrow the single most important thing he would be remembered for is the discovery of Norval Morrisseau. “Damn it,” he says, as though reading a crystal ball, knowing it as the truth.)

.

Oh Ahsin! my foolish brother, cried Wahbi Ahmik.

Even though I am mad enough kill you

I pity you.

Did it not ever cross your mind who Nimkey Banasik was?

You must know her name means Thunderbird Woman.

I would have told you

if not for your blind hatred.

I would have also told you

she had six sisters.

Can you not imagine the power our children would have had?

What it would have meant for all of us.

For this woman was a Thunderbird

in human form.

And now it is too late.

.

To say that Morrisseau is Pollock’s cash cow and he is only in it for the money would not be fair unless one put it in perspective and said that Morrisseau is everybody’s cash cow. (For this reason he is never alone.) No, safe to say there is something more between them. For Morrisseau their initial meeting is no accident. There is no room for accidents, or luck for that matter, in his belief system.

.

I am leaving to never return until I find this woman

Wahbi Ahmik said, as he turned his back on his brother

and followed the blood trail

that led far into the great forest.

For many moons he traveled until he came to a huge mountain

that reached over the clouds and beyond.

And he began to climb higher and higher

Until the earth disappeared and he reached the summit.

And there before him on a blanket of cloud

stood a towering teepee

shooting forth

lightning

and thunder

across the sky.

.

To be sure, whatever their frailties, together they are magnificent. It is as if together they walk on clouds. Pollock reads Morrisseau’s mind like a cup of tea leaves and reminds him of his purpose and stature, prodding and coaxing to get the best out of him.

.

From the majestic edifice came the laughter of women

which suddenly stopped.

For they felt his presence.

Then the teepee flap opened and there stood Nimkey Banasik

looking more beautiful than ever.

With concern she asked why he had follow her.

Because you are my life, he answered.

She smiled upon hearing his words

And beckoned him forward.

Come inside, she said,

And we will give you the power

to walk on clouds.

.

Pollock knows the painter can handle scale, which he proved in My Four Wives and Some of My Friends, both of them an impressive 109.8 cm x 332.7 cm. What he doesn’t know is that Morrisseau has also done sets of paintings, diptyches, like Merman and Merwoman, and has played with perspective in The Gift where he divided the canvas into two panes. The problem is that Morrisseau is living in Winnipeg, and this makes it nearly impossible for Pollock to keep track of him. He knows the artist is up to his old tricks of selling his work to the first person that approaches him with a few dollars rather than go through the trouble of bundling up the work and sending it off. The temptation of a quick money fix has always been one of his greatest failings. “Something the bastards are quick to seize upon,” Pollock says. The challenge is therefore not to keep him painting, which he does naturally, but to make sure he sends what he does to the gallery.

.

Inside the wigwam were seated two old thunderbirds

in human form.

Light radiated from their eyes

Suggesting a presence full of power and wisdom.

Immediately they saw Wahbi Ahmik’s hunger

and offered him food.

In an instant a roar of deafening thunder erupted

As they stretched out their arms and changed into thunderbirds

and flew away

To return with a big horned snake with two heads and three tails.

They offered it to Wahbi Ahmik to eat

but he quickly turned away from writhing mass of flesh.

The next morning they again asked him if he needed food.

and the thunderbirds returned with a black snake sturgeon

and later with a cat-like demigod.

And Wahbi Ahmik grew weaker

and weaker.

.

Pollock flies back and forth between Toronto and Winnipeg, making sure that Morrisseau is not going astray, and takes whatever paintings the artist has finished. Bob Checkwitch of Great Grassland Graphics is also working with the painter during this time doing a series of prints and helps to keep him in check. Through meetings, telephone calls and letters Morrisseau and Pollock discuss the concept for Man Changing Into Thunderbird and after much discussion Morrisseau decides to translate the story into a series of panels. Like Pollock, Morrisseau knows this will be his greatest work to date.

.

Finally the old woman who feared that Wahbi Ahmik was starving

told her daughter to take him

to her great medicine uncle

Southern Thunderbird

whom she knew would have strong medicine for the human.

They laid Wahbi Ahmik on a blanket of cloud

softer than rabbit fur and wrapped him gently

so that he would not see.

And with the thunder suddenly erupting

Wahbi Ahmik felt his nest of cloud move.

After what seemed like a mere moment

They stopped

and his wife Nimkey Banasik

removed the cloud from around him .

And there in front of Wahbi Ahmik

perched on a cloud

stood a great medicine lodge.

.

Three weeks before the opening, which is scheduled for August 10that 2:00 pm, Pollock receives four panels, but he can see that the series is incomplete. Another two weeks pass and he starts to become anxious. He telephones Winnipeg and Morrisseau assures him that he will bring them to Toronto with him. Pollock warns him that he needs time to prepare the paintings. They have to be stretched and framed. Again Morrisseau tells him not to worry.

.

Nimkey Banasik looked around him and saw many lodges

the homes of many different kinds of thunderbirds

All in human form.

Entering the great medicine lodge

Nimkey Banasik brought her uncle greeting from her mother

And beseeched him for help.

My mother said that you would have medicine for my husband

so that he may eat as we do

And perhaps even become one of us.

The old thunderbird stood in silence pondering the love between them

and the consequences

of such an action.

Let it be known that if this human takes my medicine

He will never return to earth

but will become a thunderbird forever.

Then the medicine thunderbird took two small blue medicine eggs

mixed them together

And advised Wahbi Ahmik to drink it.

.

On Friday, August 9th Morrisseau saunters into the gallery about lunchtime. Under his arm is the roll that Pollock is expecting. Everyone breaks off installing the show and gathers around to see the last few panels. Morrisseau grins as he unrolls two blank canvasses. As Pollock tells it, he is stunned. It’s the last straw, and he barks and growls at the artist who calmly assures him that the pictures will be finished in time for the show. Pollock exclaims that the other panels are still at the framer’s and he won’t be able to use them for reference. No problem, Morrisseau says, unmoved by the calamity that Pollock foresees.

.

The moment the potion entered Wahbi Ahmik

he felt a strange power surge throughout his body.

Looking at his hands and feet he saw

they were no longer human

but of the claws and wings of a thunderbird.

With the next drink the change was complete.

He was now a thunderbird.

His human form, the wigwams, the great medicine lodge

All disappeared.

Everyone was now a thunderbird

inhabiting the realm of thunderbirds.

And so Wahbi Ahmik and Nimkey Banasik

thanked Southern Thunderbird

and flew home together

where Wahbi Ahmik feasted

on thunderbird food

and lived out his life with this beloved wife Nimkey Banasik.

.

Morrisseau purchases ten brushes and twenty tubes of paint from Daniel’s Art Supplies up the street from his hotel. For the life of him Pollock cannot fathom how he is going to execute the paintings, how he can possibly carry in his head the complete chromatic palette of the first four panels. As he is leaving the room Morrisseau tells him to come back at one o’clock in the morning and he’ll have the paintings ready for him. Not knowing what to expect, Pollock returns at the exact hour. Morrisseau swings open the door to his room, and there they are laid out on the floor. He has finished the series with two more panels. The moment Pollock sees them it becomes clear to him that the artist has not only successfully recreated the colours of the first four panels, but he has somehow managed to keep in his head both their composition and scale. They are exactly like the originals. He is stunned. With the canvasses still wet, Pollock carries them back to the gallery in his outstretched arms and takes them for framing the moment they are dry. The show opens on time with Morrisseau touching up the new panels with daps of paint on the tip of his right index finger. Within one hour the complete set of six panels is sold. Everyone who is witness to the work is awestruck.

.

And the people who remained below

in the world of humans

generation upon generation

remember Wahbi Ahmik

as the Man Who Changed

Into

A Thunderbird.

. . . . .

.

ZP_Norval Morrisseau_Man Changing into Thunderbird_1977_panel 6 of 6

ZP_Norval Morrisseau_Man Changing into Thunderbird_1977_panel 6 of 6

.

Norval Morrisseau is considered by art historians, critics and curators alike as one of the most innovative artists of the 20th century. Among his awards and honours were the Order of Canada and the Aboriginal Achievement Award. Referred to as the “Picasso of the North” by the French press, he was the only Canadian painter invited to France to celebrate the bi-centennial of the French Revolution in 1989. A self-taught painter, Norval Morrisseau came to the attention of the Canadian art scene in 1962 with his first solo and break-through exhibition at Pollock Gallery in Toronto. This sold-out show announced the arrival of an artist like no other in the history of Canadian art. In the first ever review of his work, Globe and Mail art critic Pearl McCarthy declared him a “genius.” Born in 1932 in the isolated Ojibway community of Sand Point in northwestern Ontario, and having lived a tumultuous life of extreme highs and lows, Norval Morrisseau died in Toronto in 2007.

Drawing initially on the iconography of traditional First Nations sources, in particular the sacred birch-bark scrolls and the pictographs (prehistoric ‘rock art’) of the Algonquin-speaking peoples, Morrisseau went on to incorporate a wide array of contemporary influences in his art, ranging from the techniques of modernist painters and the imagery of comic books and magazines, to ‘new age’ philosophy. Continually evolving as a painter, he quickly eschewed the label “primitive artist”, becoming renowned for his daring experiments with imagery, scale, and colour. Following on the heels of Morrisseau’s success, a younger generation of painters, both Native and non-Native, followed in his style, becoming known as the “Woodland School of Painters,” the only indigenous school of painting to emerge in Canada.

.

ZP_Norval Morrisseau’s name written in Ojibwe syllabics

ZP_Norval Morrisseau’s name written in Ojibwe syllabics

ZP_Norval Morrisseau in 1977_photograph by Dick Loek_Toronto Star newspaper

ZP_Norval Morrisseau in 1977_photograph by Dick Loek_Toronto Star newspaper

.

Armand Garnet Ruffo draws on his Ojibway heritage for much of his writing. Born in Chapleau, northern Ontario, with roots to the Sagamok Ojibway First Nation and the Chapleau Fox Lake Cree First Nation, he currently lives in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, and teaches in the Department of English at Carleton University. His works include Grey Owl: the Mystery of Archie Belaney (Coteau Books) and At Geronimo’s Grave(Coteau Books). His poetry, fiction and non-fiction continue to be published widely. In 2009, he co-authored “Indigenous Writing: Poetry and Prose” for The Cambridge History of Canadian Literature, and, in 2013, he co-edited An Anthology of Canadian Native Literature in English for Oxford University Press. In 2010, his feature film “A Windigo Tale” won Best Picture at the 35th American Indian Film Festival in San Francisco.

The Thunderbird Poems will be published by Insomniac Press in 2014.

. . . . .

Jaime Sabines: “Message to Rosario Castellanos” / “Recado a Rosario Castellanos”

Posted: October 8, 2013 Filed under: English, Jaime Sabines, Spanish Comments Off on Jaime Sabines: “Message to Rosario Castellanos” / “Recado a Rosario Castellanos”Jaime Sabines (Chiapas, 1926 – México City, 1999)

“Message to Rosario Castellanos”

(Translation from Spanish into English: Paul Claudel and St.John Perse)

.

Only a fool could devote a whole life to solitude and love.

Only a fool could die by touching a lamp,

if a lighted lamp,

a lamp wasted in the daytime is what you were.

Double fool for being helpless, defenceless,

for going on offering your basket of fruit to the trees,

your water to the spring,

your heat to the desert,

your wings to the birds.

Double fool, double Chayito*, mother twice over,

to your son and to yourself.

Orphan and alone, as in the novels,

coming on like a tiger, little mouse,

hiding behind your smile,

wearing transparent armour,

quilts of velvet and of words,

over your shivering nakedness.

.

How I love you, Chayo*, how I hate to think

of them dragging your body – as I’m told they did.

Where did they leave your soul?

Can’t they scrape it off the lamp,

get it up off the floor with a broom?

Don’t they have brooms at the Embassy?

How I hate to think, I tell you, of them taking you,

laying you out, fixing you up, handling you,

dishonouring you with the funeral honours.

(Don’t give me any of that

Distinguished Persons fucking stuff!)

I hate to think of it, Chayito!

And this is all? Sure it’s all. All there is.

At least they said some good things in The Excelsior*

and I’m sure there were some who cried.

They’re going to devote supplements to you,

poems better than this one, essays, commentaries

– how famous you are, all of a sudden!

Next time we talk

I’ll tell you the rest.

.

I’m not angry now.

It’s very hot in Sinaloa.

I’m going down to have a drink at the pool.

.

*Chayito / Chayo – nicknames for the name Rosario i.e. Little Rosary/Rosa/Rosie

*El Excélsior – a México City daily newspaper

. . .

“Recado a Rosario Castellanos”

.

Sólo una tonta podía dedicar su vida a la soledad

y al amor.

Sólo una tonta podía morirse al tocar una lámpara,

si lámpara encendida,

desperdiciada lámpara de día eras tú.

Retonta por desvalida, por inerme,

por estar ofreciendo tu canasta de frutas a los árboles,

tu agua al manantial,

tu calor al desierto,

tus alas a los pájaros.

Retonta, re-Chayito, remadre de tu hijo y de ti misma.

Huérfana y sola como en las novelas,

presumiendo de tigre, ratoncito,

no dejándote ver por tu sonrisa,

poniéndote corazas transparentes,

colchas de terciopelo y de palabras

sobre tu desnudez estremecida.

.

¡Como te quiero, Chayo, como duele

pensar que traen tu cuerpo! – así se dice –

(¿Dónde dejaron tu alma? ¿ No es posible

rasparla de la lámpara,

recogerla del piso con una escoba?

¿Qué, no tiene escobas la Embajada?)

¡Cómo duele, te digo, que te traigan,

te pongan, te coloquen, te manejen,

te lleven de honra en honra funerarias!

(¡No me vayan a hacer a mi esa cosa

de los Hombres Ilustres, con una chingada!)

¡Como duele, Chayito!

¿Y esto es todo? ¡ Claro que es todo, es todo!

Lo bueno es que hablan bien en el Excélsior

y estoy seguro de que algunos lloran,

te van a dedicar tus suplementos,

poemas mejores que éste, estudios, glosas,

¡qué gran publicidad tienes ahora!

La próxima vez que platiquemos

te diré todo el resto.

.

Ya no estoy enojado.

Hace mucho calor en Sinaloa.

Voy a irme a la alberca a echarme un trago.

. . .

Rosario Castellanos – poet, author, essayist – was born into a “Ladino” (Hispanicized Mestizo) landowning family in Chiapas. From her mid-teens onward she lived in México City, where she would gradually become one of the so-called “Generation of 1950” – post-War writers of Latin America. Throughout her life – cut short by a freak domestic electrical accident involving a lamp while she was leaving her bath in Tel Aviv – where she had been posted as Mexican ambassador – she wrote with passion and precision about what now we would call “cultural and gender oppression”. Her 1962 novel Oficio de Tinieblas(The Book of Lamentations in its English translation) is an empathetic yet trenchant imagining of the conflicts between Tzotzil Mayans and “Ladinos” leading up to agrarian reform in her ancestral Chiapas. Castellanos is important today for opening the doors to a Mexican Feminist world-view through her frank and insightful poetry, novels, and newspaper essays.

. . .

Rosario Castellanos – poeta y novelista – nació en la Ciudad de México en 1925. Su infancia y parte de su adolescencia la vivió en Comitán y en San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas.

Dedicó una parte de su obra y de sus energías a la defensa de los derechos de las mujeres, labor por la que es recordada como uno de los símbolos del feminismo latinoamericano. A nivel personal, su propia vida estuvo marcada por un matrimonio infeliz y depresiones múltiples que la llevaron en más de una ocasión a ser ingresada.

Su obra incluye la novela Oficio de Tinieblas (1962) – trata de reforma agraria y tensiones sociales entre los tzotziles y los ladinos en el campo de Chiapas – también el poemario Poesía no eres tú (1972).

En 1971, Castellanos fue nombrada embajadora de México en Israel, desempeñándose como catedrática en la Universidad Hebrea de Jerusalén, además de su labor de diplomática. Falleció en Tel Aviv en agosto de 1974 – a consecuencia de una descarga eléctrica provocada por una lámpara cuando acudía a contestar el teléfono al salir de bañarse. Sus restos fueron trasladados a La Rotonda de los Hombres Ilustres (ahora La Rotonda de las Personas Ilustres) en la Ciudad de México.

. . . . .

Jaime Sabines: “Before the ice of silence descends on my tongue…” / “Antes de que caiga sobre mi lengua el hielo del silencio…”

Posted: October 8, 2013 Filed under: English, Jaime Sabines, Spanish Comments Off on Jaime Sabines: “Before the ice of silence descends on my tongue…” / “Antes de que caiga sobre mi lengua el hielo del silencio…”Jaime Sabines (Born in Chiapas, 1926 – died in México City, 1999)

. . .

“On Hope”

.

Occupy yourselves here with hope.

The joy of the day that’s coming

buds in your eyes like a new light.

But that day that’s coming isn’t going to come: this is it.

. . .

“De la esperanza”

.

Entreteneos aquí con la esperanza.

Es júbilo del día que vendrá

os germina en los ojos como una luz reciente.

Pero ese día que vendrá no ha de venir: es éste.

. . .

“On Illusion”

.

On the tablet of my heart you wrote:

Desire.

And I walked for days and days,

mad and scented and dejected.

.

“De la ilusión”

.

Escribiste en la tabla de mi corazón:

Desea.

Y yo anduve días y días,

loco, aromado, y triste.

. . .

“On Death”

.

Bury it.

There are many silent men under the earth

who will take care of it.

Don’t leave it here.

Bury it.

“De la muerte”

.

Enterradla.

Hay muchos hombres quietos, bajo tierra,

que han de cuidarla.

No la dejéis aquí –

Enterradla.

. . .

“On Myth”

.

My mother told me that I cried in her womb.

They said to her: he’ll be lucky.

.

Someone spoke to me all the days of my life

into my ear, slowly, taking their time.

Said to me: live, live, live!

It was Death.

.

“Del mito”

.

Mi madre me contó que yo lloré en su vientre.

A ella le dijeron: tendrá suerte.

.

Alguien me habló todos los días de mi vida

al oído, despacio, lentamente.

Me dijo: ¡vive, vive, vive!

Era la Muerte.

. . .

If I were going to die in a moment, I would write these words of wisdom: tree of bread and honey, rhubarb, coca-cola, zonite, swastika. And then I would start to cry.

.

You can start to cry even at the word “excused” if you want to cry.

.

And this is how it is with me now. I’m ready to give up even my fingernails, to take out my eyes and squeeze them like lemons over the cup of coffee.

(“Let’s have a cup of coffee with eye peel, My Heart”).

.

Before the ice of silence descends on my tongue, before my throat splits and my heart keels over like a leather sack, I want to tell you, My Life, how grateful I am for this stupendous liver that let me eat all your roses on the day when I got into your hidden garden without anyone seeing me.

.

I remember it. I filled my heart with diamonds – they are fallen stars that have aged in the dust of the earth – and it kept jingling like a tambourine when I laughed. The only thing that really annoys me is that I could have been born sooner and I didn’t do it.

.

Don’t put love into my hands like a dead bird.

Si hubiera de morir dentro de unos instantes, escribiría estas sabias palabras: árbol del pan y de la miel, ruibarbo, coca-cola, zonite, cruz gamada. Y me echaría a llorar.

.

Uno puede llorar hasta con la palabra “excusado” si tiene ganas de llorar.

.

Y esto es lo que hoy me pasa. Estoy dispuesto a perder hasta las uñas, a sacarme los ojos y a exprimirlos como limones sobre la taza de café.

(“Te convido a una taza de café con cascaritas de ojo, corazón mío”).

.

Antes de que caiga sobre mi lengua el hielo del silencio, antes de que se raje mi garganta y mi corazón se desplome como una bolsa de cuero, quiero decirte, vida mía, lo agradecido que estoy, por este higado estupendo que me dejó comer todas tus rosas, el día que entré a tu jardín oculto sin que nadie me viera.

.

Lo recuerdo. Me llené el corazón de diamantes – que son estrellas caídas y envejecidas en el polvo de la tierra – y lo anduve sonando como una sonaja mientras reía. No tengo otro rencor que el que tengo, y eso porque pude nacer antes y no lo hiciste.

.

No pongas el amor en mis manos como un pájaro muerto.

I take pleasure in the way the rain beats its wings on the back of the floating city.

.

The dust comes down. The air is left clean, crossed by leaves of odour, by birds of coolness, by dreams. The sky receives the city that is being born.

.

Streetcars, buses, trucks, people on bicycles and on foot, carts of all colours, street-vendors, bakers, pots of tamales, grilles of baked bananas, balls flying between one child and another: the streets swell, the sounds of voices multiply in the last light of the day hung up to dry.

.

They come out like ants after the rain, to pick up the crumb of the sky, the little straw of eternity to take away to their dark houses, with cuttlefish hanging from the roofs, with weaving spiders under the beds, and with one familiar ghost, at least, in back of some door.

.

Thanks be to you, Mother of the Black Clouds, who have so whitened the face of the afternoon and have helped us to go on loving life.

. . .

Me gustan los aletazos de la lluvia sobre los lomos de la ciudad flotante.

.

Desciende del polvo. El aire queda limpio, atravesado de hojas de olor, de pájaros de frescura, de sueños. El cielo recibe a la ciudad naciente.

.

Tranvías, autobuses, camiones, gentes en bicicleta y a pie, carritos de colores, vendedores ambulantes, panaderos, ollas de tamales, parrillas de plátanos horneados, pelotas de un niño al otro: crecen las calles, se multiplican los rumores en las últimas luces del día puesto a secar.

.

Salen, como las hormigas después de la lluvia, a recoger la migas del cielo, la pajita de la eternidad que han de llevarse a sus casas sombrías, con pulpos colgando del techo, con arañas tejedoras debajo de la cama, y con un fantasma familiar, cuando menos, detrás de alguna puerta.

.

Gracias te son dadas, Madre de las Nubes Negras, que has puesto tan blanca la cara de la tarde y que nos has ayudado a seguir amando la vida.

. . .

Before long you will offer these pages to people you don’t know as though you were holding out a handful of grass that you had cut.

.

Proud and depressed of your achievement you will come back and fling yourself into your favourite corner.

.

You call yourself a poet because you don’t have enough modesty to remain silent.

.

Good luck to you, thief, with what you’re stealing from your suffering – and your loves! Let’s see what sort of image you make out of the pieces of your shadow you pick up.

. . .

Dentro de poco vas a ofrecer estas páginas a los desconocidos como si extendieras en la mano un manojo de hierbas que tú cortaste.

.

Ufano y acongojado de tu proeza, regresarás a echarte al rincón preferido.

.

Dices que eres poeta porque no tienes el pudor necesario del silencio.

.

¡Bien te vaya, ladrón, con lo que le robas a tu dolor y a tus amores! ¡A ver qué imagen haces de ti mismo con los pedazos que recoges de tu sombra!

.

You have what I look for, what I long for, what I love – you have it.

The fist of my heart is beating, calling.

I thank the stories for you.

I thank your mother and your father and death who has not seen you.

I thank the air for you.

You are elegant as wheat,

delicate as the outline of your body.

I have never loved a slender woman

but you have made my hands fall in love,

you moored my desire,

you caught my eyes like two fish.

And for this I am at your door, waiting.

. . .

Tú tienes lo que busco, lo que deseo, lo que amo – tú lo tienes.

El puño de mi corazón está golpeando, llamando.

Te agradezco a lo cuentos,

doy gracias a tu madre y a tu padre,

y a lo muerte que no te ha visto.

Te agradezco al aire.

Eres esbelta como el trigo,

frágil como la línea du tu cuerpo.

Nunca he amado a mujer delgada

pero tú has enamorado mis manos,

ataste mi deseo,

cogiste mis ojos como dos peces.

Por eso estoy a tu puerta, esperando.

. . .

From: Selected Poems of Jaime Sabines: Pieces of Shadow

Translations from Spanish into English © W.S. Merwin (1995)

.

. . .

Jaime Sabines (1926-1999) was born in Tuxtla Gutiérrez in the state of Chiapas, México.

At 19 he moved to México City, studying Medicine for three years, then switching to Philosophy and Literature at UNAM (University of México). He published eight volumes of poetry, including Horal (1950), Tarumba (1956), and Maltiempo (1972), receiving the Xavier Villaurrutia Award for the latter. He was granted the Chiapas Prize in 1959 and the National Literature Award in 1983. He also served as a congressman for Chiapas. Octavio Paz called Sabines one of the handful of poets that comprised the beginning of Modern Latin-American Poetry. For such poets the aim of the poem was not – as before – to invent, rather to explore. In a 1970s interview Sabines observed: “No subject matter can be forced upon the poet. He must be a witness to his times. Must discover reality and recreate it. He should speak of that which he lives and experiences. I feel that a poet must first of all be authentic; I mean by this that there must be a correspondence between his personal world and the world that surrounds him. If you have a mystical inclination – why not write about it? If you live alone and are afflicted by your solitude – why not speak about it, if it is yours? Poetry must bear witness to our everyday lives.”

.

La obra de Jaime Sabines (1926-1999) representa, dentro de la poesía mexicana contemporánea, una isla que se vincula con la realidad a través de puentes inexorables: la muerte, la inquietud social, la angustia por la existencia, la presencia o la ausencia de Dios y – fundamentalmente – el amor. El amor es – en un poema de Sabines – no sólo un sentimiento sino también una herramienta – un clave personal – para comunicarse no sólo con la mujer sino con el mundo. Sabines fue el más notable precursor de la poesía coloquial en América Latina. (Mario Benedetti, 2007)

. . . . .

Les femmes-poètes africaines “griotent” de la Poésie, de l’Amour, du Néant – et de la Jupe / African women poets sing, proclaim, and advise about Poetry, about Love, The Void – and Skirts

Posted: October 1, 2013 Filed under: English, French | Tags: Femmes-Poètes Africaines Comments Off on Les femmes-poètes africaines “griotent” de la Poésie, de l’Amour, du Néant – et de la Jupe / African women poets sing, proclaim, and advise about Poetry, about Love, The Void – and Skirts ZP_Werewere Liking reciting at the Festival Internacional de Poesía de Medellín in Colombia_2011

ZP_Werewere Liking reciting at the Festival Internacional de Poesía de Medellín in Colombia_2011

.

Assamala Amoi (born 1960, Paris / Abidjan, Ivory Coast)

“If you could”

.

If you could leave when work was done

Like the sun at the end of its day;

If you could arrive like the day and the night

At an hour chosen by the seasons;

If you could hear the farewells like the tree

Listens to the song of the migrating bird

– who would dread departures, returns and death?

. . .

“Si on pouvait”

.

Si on pouvait s’en aller à la fin de son ouvrage

Comme le soleil au terme de sa course;

Si on pouvait arriver comme le jour et la nuit

A l’heure choisie par les saisons;

Si on pouvait entendre les adieux comme l’arbre

Ecoute le chant de l’oiseau qui le quitte

Qui craindrait les départs, les retours et la mort?

. . .

Dominique Aguessy (born 1937, Benin)

“The poem seeks its own way”

.

The poem seeks its own way

Nestled in the parchment’s heart

Elegantly inscribed

By a sure and decided hand

While ideas wait to be set free

By the force of the poet

Expecting she will intercede

Bringing them alive

Without an excess of prejudice

Will she choose simplicity,

Or more exuberance, more spontaneity

Or still more circumspection?

From the madness of colours

To the vertigo of flavours

From the combinations of archipelagos

Drafting the sensual structures

The sap of the words sows images

Multiple trials bear witness

Disclosing the singular essence

Of eternal idle wandering.

. . .

“Le poème poursuit son chemin”

.

Le poème poursuit son chemin

Niché au coeur du parchemin

Elégamment buriné

D’une main ferme et décidée

Tandis que les idées

Attendent d’être délivrées

Par la vertu de l’aède

Espèrent qu’il intercède

Les amène à la vie

Sans trop de parti pris

Optera-t-il pour la simplicité,

Davantage d’exubérance, de spontanéité

Ou plus encore de retenue?

De la folie des couleurs

Au vertige des saveurs

Des combinaisons d’archipels

Ebauchent des structures sensuelles

La sève des mots ensemence les images

De multiples essais rendent témoignage

Dévoile l’essence originelle

De vagabondages sempiternels.

. . .

“When sudden passion comes”

.

When sudden passion comes

There is no age of reason

There is no future to protect

There are no inquisitors to mislead.

.

Who dares to touch it is stung

Who comes near it is consumed

Who speaks of it becomes ignorant

Who says nothing is reborn.

. . .

“Quand survient la passion”

.

Quand survient la passion

Il n’est pas d’âge de raison

Ni de futur à préserver

D’inquisiteurs à déjouer

.

Qui s’y frotte s’y pique

Qui s’en approche s’y consume

Qui en disserte l’ignore

Qui se tait en renaît.

. . .

Fatou Ndiaye Sow (1956-2004, Senegal)

“On the Threshold of Nothingness”

.

In this vampire world,

Here I am filled with my exile.

Let me rediscover

The Original Baobab

Where the Ancestor sleeps

In the deep murmur

Of his original solitude.

Let my eyes gleam

With a myriad of suns,

Voyaging across time and space without shores

And dissolving into faith the cries of anguish

And fishing for glimmers of hope

In the purple horizon of dusk

To ennoble rapacious humanity

Executioner or victim

In search of a distant star

Distant

Hidden behind doors of silence

Inside the Universe of hope

Let me decipher

At the foot of the Original Baobab

The message of my cowrie shells

Where I read

That every epoch lives its drama

Every people their suffering

But that before the doors of Nothingness

Each one PAUSES and THINKS.

. . .

“Au seuil du néant”

.

Dans ce monde vampire,

Me voilà remplie de mon exil.

Laissez-moi redécouvrir

Le Baobab Originel

Où dort l’Aïeul

Dans la rumeur profonde

De sa solitude première.

Laissez mon oeil éclaté

De myriades de soleils,

Voyager dans l’espace-temps sans rivages

Et dissoudre dans la foi les râles de l’angoisse,

Et pêcher des éclats d’espoir

Dans l’horizon pourpre du couchant

Pour ennoblir le rapace humain

Bourreau ou victime

A la recherche d’une étoile lointaine

Lointaine

Cachée aux portes du silence.

Dans l’Univers de l’espérance

Laissez-moi déchiffrer

Au pied du Baobab Originel

Le message de mes cauris,

Où je lis

Que chaque époque vit son drame

Chaque peuple ses souffrances

Mais qu’aux portes du Néant

Chacun S’ARRÊTE et PENSE.

. . .

Clémentine Nzuji (born 1944, Tshofa, Zaïre/Democratic Republic of Congo)

“It’s not my fault…”

.

It’s not my fault

If no one understands me

If I must

Express myself in

An absurd language

.

The trees also

and the winds

the flowers

and the waters

Express themselves in their own way

Strange to human beings

.

Take me as a tree

as wind

as flower

or as water

If you want to understand me.

. . .

“Ce n’est pas ma faute…”

.

Ce n’est pas ma faute

Si personne ne me comprend

Si j’ai

Pour m’exprimer

Un langage absurde

.

Les arbres aussi

les vents

les fleurs

et les eaux

S’expriment à leur manière

Etrange pour les humains

.

Prenez-moi pour arbre

pour vent

pour fleur

ou pour eau

Si vous voulez me comprendre.

. . .

Hortense Mayaba (born 1959, Djougou, Benin)

“When Life Ends”

.

A life ends

Another begins

We are the descendents

Of our dead

Each family keeps their own

Every being keeps their lineage

Our sleep makes them live again

In us they are reborn each night

Wearing our tattered clothes

Moving with our limbs

Walking often in our shadows

Drunk with our desires

And vanishing with our waking

When Life Ends!

. . .

“Quand la vie s’éteint”

.

Une vie s’éteint

Une autre renaît

Nous sommes les descendants

De nos morts

Chaque famille conserve les siens

Chaque être conserve sa lignée

Notre sommeil les fait revivre

Ils renaissent chaque nuit en nous

S’habillent de nos guenilles

Se mouvant de nos membres

Marchant souvent dans nos ombres

S’enivrant de nos désirs

Et s’évanouissant en nos réveils.

Quand la vie s’éteint!

. . .

“The Great Eye of the Good Lord”

.

I tried to find

Where the moon came from,

That princess

The colour of silver

.

I wanted to understand

Where the moon went,

That princess

Who lights up the sky

.

I tried to discover

Who commands the moon,

That princess

Of Africa’s nights

.

At last I understood

What the moon was,

That princess of the sky –

She is the Great Eye of the Good Lord.

. . .

“Le gros oeil du Bon Dieu”

.

J’ai cherché à savoir

D’où venait la lune,

Cette princesse

Couleur d’argent

.

J’ai voulu comprendre

Où allait la lune,

Cette princesse

Qui illumine le ciel

.

J’ai tenté de découvrir

Qui commandait à la lune,

Cette princesse

Des nuits d’Afrique

.

J’ai enfin compris

Ce qu’était la lune,

Cette princesse du ciel –

C’est le gros oeil du Bon Dieu.

. . .

Werewere Liking (born 1950, Cameroon)

“To Be Able”

.

There are words like a balm

They sweeten and leave a taste of mint

There are gazes like the wool of a lamb

They enfold and warm like a caress

There are smiles like full moons

They enlighten with intimacy

.

To be able!

Able to look

Able to discover

Able to predict

Able to feel

And be happy!

.

There are intoxicating promiscuities

And soft touches like caresses of sunlight

Furtive and discrete and exciting

They leave a taste of anticipation!

.

To be able

Able to feel

And be happy!

.

There are alarming caresses

That leave one on guard

And there are names that foretell fate

And phrases like decrees.

.

To be able to discover

To be able

And be happy!

.

There are faces like proverbs

Enigmatic and symbolic

They call up wisdom

Because life is the future

And the future is you

.

Ah, to be able

Able to predict

And be happy!

.

There are marvelous beauties

Present and numerous there

Under the nose there before our eyes

.

To be able

Ah, able to look

Yes, able to see

Because to see is to understand

That love

That happiness

Is as true

And as near

As your being here.

. . .

“Pouvoir”

.

Il est des mots comme des baumes

Ils adoucissent et laissent un goût de menthe

Il est des regards comme de la laine d’agneau

Ils enveloppent et réchauffent dans la caresse

Il est des sourires comme des pleines lunes

Ils illuminent avec intimité

.

Pouvoir!

Pouvoir regarder

Pouvoir déceler

Pouvoir deviner

Pouvoir sentir

Et être heureux!

.

Il est des promiscuités enivrantes

Et des frôlements comme des caresses de soleil

Furtives et discrètes et excitantes

Elles laissent un goût d’attente!

.

Pouvoir

Pouvoir sentir

Et être heureux!

.

Il est des caresses alarmantes

Qui laissent sur le qui-vive!

Il est des noms qui augurent du destin

Et des phrases comme des décrets.

.

Pouvoir déceler

Pouvoir

Et être heureux!

.

Il est des visages comme des proverbes

Enigmatiques et symboliques

Ils appellent à la sagesse

Parce que la vie c’est l’avenir

Et que l’avenir c’est toi

.

Ah, pouvoir

Pouvoir deviner

Et être heureux!

.

Il est beautés merveilleuses

Présentes et nombreuses là

Sur le nez là sous nos yeux

.

Pouvoir

Ah, pouvoir regarder

Oui pouvoir voir

Car voir c’est comprendre

Que l’amour

Que le bonheur

C’est aussi vrai

Et aussi près

Que tu es là.

. . .

Monique Ilboudo (born 1959, Burkina Faso)

“Skirts”

.

I don’t like skirts

Not short ones

Not long ones

Not straight ones

Not pleated ones

.

I don’t like skirts

The short ones show me

The long ones slow me

The straight ones smother me

The pleated ones oppress me

.

I don’t like skirts

Pretty or ugly

Red or green

Short or long

Straight or pleated

.

I don’t like skirts

Except if they’re culottes…

But the long pleated skirt

That’s the worst of all!

I don’t like skirts.

“Les jupes”

.

J’aime pas les jupes

Ni les courtes

Ni les longues

Ni les droites

Ni les plissées

.

J’aime pas les jupes

Les courtes m’exhibent

Les longues m’entravent

Les droites m’étouffent

Les plissées m’encombrent

.

J’aime pas les jupes

Belles ou laides

Rouges ou vertes

Courtes ou longues

Droites ou plissées

.

J’aime pas les jupes

Sauf si elles sont culottes…

Mais la jupe-longue-plissée

C’est la pire de toutes!

J’aime pas les jupes.

. . .

Nafissatou Dia Diouf (born 1973, Senegal)

“Tell Me…”

.

If what you have to say

Is not as beautiful as silence

Then, say nothing

Because nothing is more beautiful

Than your mouth half-open

On a hanging word

.

Tell me the unspeakable

Tell me the unname-able

Tell me with words

That will melt into nothingness

As soon as you speak them

.

Tell me what is on the other side of the mirror

Behind your eyes without silvering

Tell me your life, tell me your dreams

Tell me your grief and also your hopes

And I will live them with you

.

In the world of silence and rustling silk

Of velvet gazes and quilted caresses

Now, everything has been said

Or almost

So hussssssssh……

. . .

“Dis-moi…”

.

Si ce que tu as à dire

N’est pas aussi beau que le silence

Alors, tais-toi

Car il n’y a rien de plus beau

Que ta bouche entrouverte

Sur une parole arrêtée

.

Dis-moi l’indicible

Dis-moi l’innommable

Dis-le moi avec les mots

Qui se fondront dans le vide

Aussitôt prononcés

.

Dis-moi ce qu’il y a de l’autre côté du miroir

Derrière tes yeux sans tain

Dis-moi ta vie, dis-moi tes rêves

Dis-moi tes peines et tes espoirs aussi

Et je les vivrai avec toi

.

Dans un monde de silence et de soie crissante

De regards veloutés et de caresses ouatées

A présent, tout a été dit

Ou presque

Alors chuuuuuuuut……

. . . . .

Traductions en anglais / Translations from French into English – droit d’auteur © Professeure Janis A. Mayes. Tous les poèmes – droit de chaque auteur © the respective poetesses

. . . . .

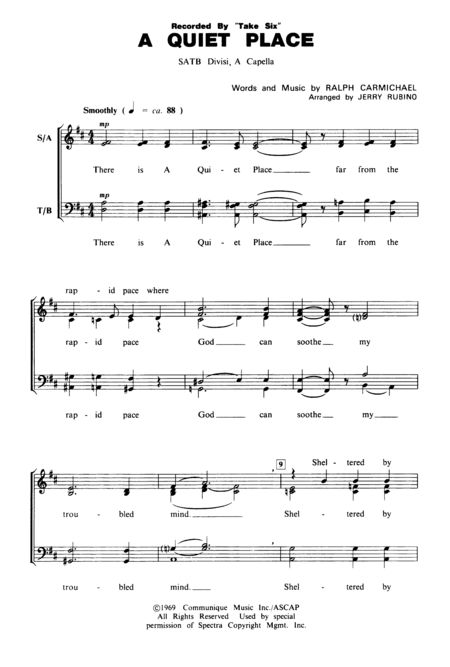

Ralph Carmichael: “Un lugar tranquilo” / “A Quiet Place”

Posted: October 1, 2013 Filed under: English, Ralph Carmichael, Spanish, Translator's Whimsy: Song Lyrics / Extravagancia del traductor: Letras de canciones traducidas por Alexander Best, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Ralph Carmichael: “Un lugar tranquilo” / “A Quiet Place”.

Ralph Carmichael (Compositor góspel, nacido 1927)

“Un lugar tranquilo”

.

Hay un lugar tranquilo

lejos del paso raudo

donde Dios puede calmar mi mente afligida.

Guardado por árbol y flor,

está allí que dejo atrás mis penas

durante la hora quieta con Él.

.

En un jardín pequeño

o alta montaña,

Encuentro allí

una nueva fortaleza

y mucho ánimo.

.

Y luego salgo de ese lugar sereno

bien listo para enfrentar un nuevo día

con amor por toda la raza humana.

. . .

Ralph Carmichael es un compositor de canciones ‘pop’ / cristianas contemporáneas.

Su canción “A Quiet Place” (“Un lugar tranquilo”) fue adaptada por un cantautor góspel estadounidense, Mervyn Warren, con su grupo “a capela” cristiano, Take 6, organizado en la Universidad Adventista Oakwood, de Huntsville, Alabama, EE.UU., durante los años 80. El arreglo musical de Señor Warren – hecho para seis voces en 1988 – es exquisitamente dulce y sensitivo. Éste no es el sonido tradicional de la música góspel, sino algo afinado y jazzístico.

Escuche la canción (versión original en inglés) en este videoclip del Festival de Jazz de Vitoria-Gasteiz (País Vasco, 1997):

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SH2orpg6ww4

. . .

Ralph Carmichael (born 1927)

“A Quiet Place” (1969)

.

There is a quiet place

far from the rapid pace

where God can soothe my troubled mind.

.

Sheltered by tree and flower

there in my quiet hour with Him

my cares are left behind.

.

Whether a garden small

or on a mountain tall

new strength and courage there I find.

.

And then from that quiet place

I go prepared to face a new day

with love for all mankind.

. . .

Ralph Carmichael is a composer and arranger of both pop music and contemporary Christian songs.

From 1962 to 1964 he arranged music for Nat King Cole, including Cole’s final hit, “L-O-V-E”.

“A Quiet Place” dates from 1969.

Mervyn Warren and Claude McKnight arranged a number of Christian songs – both traditional and “new” – for their six-part-harmony “barbershop”-style Gospel vocal sextet, Take 6.

Take 6 was formed at the Seventh-Day-Adventist college, Oakwood University, in Huntsville, Alabama in the early 1980s.

Mervyn Warren – most especially – is responsible for the exquisitely tender or playful harmonies that characterize Take 6’s unique sound. His 1988 arrangement of “A Quiet Place” is a good example of his genius as arranger. Astonishingly, Warren’s magnificent arrangements were never published or transcribed – all members learned their harmonies “in the moment” – through many hours of vocal jamming and experiment. Warren later left the group because the revelation of his homosexuality put him at cross-purposes with the Seventh-Day-Adventist credo.

Listen to Take 6 perform “A Quiet Place” (Mervyn Warren’s arrangement) on the following YouTube clip from a 1997 concert in Spain at the Festival de Jazz de Vitoria Gasteiz – their unusual Gospel sound is belovéd of Jazz aficionados, too!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SH2orpg6ww4

. . . . .

“Problematic”: Jay Bernard on poems, performance, problem-solving

Posted: August 31, 2013 Filed under: 7 GUEST EDITORS, English, Jay Bernard Comments Off on “Problematic”: Jay Bernard on poems, performance, problem-solving“Problematic”: Zócalo Poets Guest Editor Jay Bernard on poems, performance, problem-solving:

.

Poetry is a form of problem solving. There are poems and performances I return to often because they speak to – but do not necessarily solve – problems I enjoy. These problems are usually on the merry-go-round that is the relationship between society and art, and some of the pieces I mention below exemplify the kinds of problems I think about. How to speak. How to sound authentic. How to speak so you are understood. The art of incantation.

.

So let’s start with a light take on a heavy subject. Every few months I watch Tamarin Norwood (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jjMvde0GJBk) read at an event called Minimum Security Prison Poetry, then spend a few hours admiring her website. It’s a great fusion of academia and playfulness. But listen to her voice. The facetious use of arch-formalism, the repetition, the nature of the repetition, the element of the absurd. It’s the conventional voice for this style of poetry. If she was a spoken word poet, she’d gravitate towards the American slam formula in which you start with slow declarative sentences, then speed up. But sometimes the convention works. Norwood’s piece is an example, as is another favourite: Kai Davis’s Fuck I Look Like (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hGdYAK2sLjA) There’s a bit of a contradiction when she says “You say gargantuan, I say big as shit”, then goes on to criticise another student for not using big words, but her performance is a seamless combination between the voice she’d actually use in an argument and that uniquely American oratory style. She affirms my suspicions that some social problems don’t need answers, they need to be cussed out.

.

But what about the voice in other cultures? In 2012 I visited Angelica Mesiti’s Citizens Band, showing at ACCA in Melbourne. It featured four musicians with unique talents, but the one that impressed was the Mongolian throat singer. Later research yielded dozens of varieties, including the Tuvan version here at Ubuweb’s ethnopoetics page (http://www.ubu.com/ethno/soundings/tuva.html). When I taught myself to do it (you can too) the idea of the technique as a “conduit” of poetry really moved me. How else is it possible to speak? What else can our voices do? And what kind of wordless poem is created?

.

Speaking of wordlessness: Ng Yi Sheng’s performance of Singapore’s national pledge is a performance I don’t have a video for, but I wanted to include it because it’s a remarkable piece of mockery and exaggeration. Imagine: a slight, smiling man dressed as an air hostess gets up and places a pencil in his mouth. He then spends the next five minutes waving his hands around like a dictator, as he shouts lines from the national pledge to a marching rhythm. JUSTICE! JUSTICE! SOCIETY! The pencil makes him dribble. His movements exhaust him. This poem, when performed in front of Singaporean ministers, got him blacklisted. But as someone who has always been contemptuous of nationalism, I recall this performance as a great union of politics and performance. Conclusion: the more humourless the target of the joke, the better the joke.

.

Sometimes the joke is hard to get. Tongues Untied (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tWuPLxMBjM8), a 1989 film by Marlon Riggs, is the nuanced pursuit of a unified sexual/racial aesthetic. His voice, his desire to be seen as he is – dark-skinned, black, American – is complicated by his sexuality; it leads him into the white world, makes him vulnerable – neither this nor that. Yet like Norwood, there’s a lightness to his touch, and I admire the unity of his vision. Why does two identities imply a split? Why isn’t the person doubled or squared? It’s a problem that Riggs sets to song, and I return to this long, cinematic poem every year.

.

What Riggs also touches on is the yearning to say as an adult what you needed to hear as a young person; and sometimes that thing can be said not in words, but in the simple combination of *that* person, *that* voice, *that* context. Which is why Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha (http://vimeo.com/11997033) in conversation with Ellery Russian about queer crip sexuality is one of my favourite videos. The humanity in what they are saying is simple and elegant, and the same could be said generally of Samarasinha’s poetry. She writes a lot about her father’s past and how it was a mystery she had to become queer to solve. Sometimes I want the voice that wrote the poems to talk simply, humanely and intelligently about the world at large, and that is what she does here.

. . . . .

ZP Editor’s Note: To read poems by Jay Bernard, click on April 2012 and hers are right at the top.

Classic Kaiso: “Bass Man” by The Mighty Shadow

Posted: August 31, 2013 Filed under: English, English: Trinidadian, Winston Anthony Bailey Comments Off on Classic Kaiso: “Bass Man” by The Mighty Shadow ZP_The Mighty Shadow_photograph by Abigail Hadeed

ZP_The Mighty Shadow_photograph by Abigail Hadeed

.

August 31st is Independence Day in Trinidad and Tobago, and, since “we” [here at Zócalo Poets] have a sentimental attachment to Kaiso, let “us” therefore share the lyrics to an old favourite – “Bassman” by The Mighty Shadow (Winston Anthony Bailey, born 1941, Belmont, Port of Spain) – which, back in 1974, was a strikingly original Calypso tune with a new sound and instrumental arrangement: bandy-leggéd rhythms + a bunny-hoppity bass-line.

Influenced by the style of The Mighty Spoiler (Theophilus Phillip, 1926-1960), who was a great exponent of humorous and imaginative Calypsos, Shadow has had a propensity for the eccentric and the eery. Often, he has worn dark clothing with a broad-brimmed hat and regal cape; and he has the most curious movements – including a minimalist approach – when it comes to his deportment while performing. Winning first and second places in the contest for Road March 1974 – with his songs “Bassman” and “Ah Come Out To Play” – released as a 7-inch 45rpm single vinyl record the same year – Shadow was the ‘new’ calypsonian to break the stranglehold on Road March Title held for eleven years by “biggies” Kitchener and Sparrow. While Shadow came very close to winning Calypso Monarch for 1974 – certainly he was the crowd favourite – the judges didn’t agree. He would be denied the crown several seasons over before deciding to just ignore that competition – well, for 17 years, at any rate. In 1993 he re-entered for Calypso Monarch and, though he was not to win, he would comment afterwards: “I never get no crown, but they can’t touch my music. The Shadow music sweet too bad.” However, in 2000, he did finally win the Monarch title – something he’d been deserving of for many years.

As regards his musical contribution to the Calypso genre, Shadow told the Trinidad newspaper, TnT Mirror, in 1989, that his claim to fame was in “moving the bottom of the music, and introducing changes in the bass lines…My music is characterized by a lot of energy, because of my emphasis on the foot drums and bass…” Among The Mighty Shadow‘s famous songs are: Obeah (1982), Ah Come Out Tuh Party (1983), If I Wine I Wine (1985), The Garden Want Water (1988), and Mr. Brown (1996).

ZP_A 12 year old boy and member of the Tamana Pioneers steel orchestra practises his bass drums_ Arima, Trinidad_ January 2013

ZP_A 12 year old boy and member of the Tamana Pioneers steel orchestra practises his bass drums_ Arima, Trinidad_ January 2013

. . .

Winston Anthony Bailey a.k.a. The Mighty Shadow

“Bass Man”

(Music and lyrics by Bailey / Arranger: Art de Coteau)

.

I was planning to forget Calypso

And go and plant peas in Tobago

But I am afraid ah cyah make de grade.

Cuz every night I lie down in mih bed

Ah hearing a Bassman in mih head

.

Ah don’t know how dis t’ing get inside me

But e-ve-ry morning, he drivin’ me crazy

Like he takin’ me head for a pan-yard

Morning and evening, like dis fella gone mad.

Pim pom – an’ if ah don’t want to sing

Pim pom – well, he start to do he t’ing

I don’t want to – but ah have to sing

Pim pom – an’ if ah don’t want to dance

Pim pom – he does have me in a trance

I don’t want to – but ah have to prance to his:

pom pom pidi pom, pom, pom pom pidi pom, pom…

.

One night I said to de Bassman

Give me your identification

He said “Is me – Farrell –

Your Bassman from hell.

Yuh tell me you singing Calypso

An’ ah come up to pull some notes for you.”

.

Ah don’t know how dis t’ing get inside me

But e-ve-ry morning, he drivin’ me crazy

Like he takin’ me head for a pan-yard

Morning and evening, like dis fella gone mad.

Pim pom – an’ if ah don’t want to sing

Pim pom – well, he start to pull he string

I don’t want to – but ah have to sing

Pim pom – an’ if ah don’t want to dance

Pim pom – he does have me in a trance

I don’t want to – but ah have to prance to his:

pom pom pidi pom, pom, pom pom pidi pom, pom…

.

I went and ah tell Dr Lee Yeung

That I want a brain operation

A man in meh head

I want him to dead

He said it’s my imagination

But I know ah hearin’ de Bassman…

Ah don’t know how dis t’ing get inside me

But e-ve-ry morning, he drivin’ me crazy

Like he takin’ me head for a pan-yard

Morning and evening, like dis fella gone mad.

Pim pom – etcetera…..

. . . . .

Véronique Tadjo: “Cocodrilo” / “Crocodile”

Posted: August 27, 2013 Filed under: English, French, Spanish, Véronique Tadjo, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Véronique Tadjo: “Cocodrilo” / “Crocodile”

Véronique Tadjo (nacido en 1955, Paris/Abidjan, Costa de Marfil)

“Cocodrilo”

.

No es la vida fácil ser un cocodrilo

especialmente si no quiere ser un cocodrilo

El coco que usted puede ver – en la página opuesta* –

no es feliz en su

piel de coco

Era su preferencia

ser diferente

Habría preferido

llamar la atención de

Los niños

y jugar con ellos

Platicar con sus padres

Dar paseos

por la aldea

Excepto, excepto, excepto…

.

Cada vez que sale del agua

Los pescadores

tiran lanzas

Los niños

huyen

Las muchachas

abandonan sus jarros

.

Su vida es

una vida

de soledad y de la pena

Vida sin cuate y sin cariño,

sin ningún lugar a visitar

.

En todas partes – Desconocidos

.

Ese cocodrilo

Vegetariano

Un cocodrilo

y bueno para nada

Un cocodrilo

que se siente un

Horror sagrado de la sangre

.

Por favor:

Escríbale,

Escríbale a:

Cocodrilo Amable,

Caleta número 3,

Cuenca del Rio Níger.

.

*La versión original en francés presenta un dibujo hecho por Señora Tadjo.

.

Traducción en español: Alexander Best

. . .

Véronique Tadjo (née en 1955, Paris/Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire)

“Crocodile”

.

Ce n’est pas facile d’être un crocodile

Surtout si on na’a pas envie

D’être un crocodile

Celui que vous voyez

Sur la page opposée

N’est pas bien

Dans sa peau

De croco

il aurait aimé

Etre different

Il aurait aimé

Attirer

Les enfants

Jouer

Avec eux

Converser

avec les parents

Se balader

Dans

Le village

Mais, mais, mais

.

Quand il sort

De l’eau

Les pêcheurs

Lancent des sagaies

Les gamins

Détalent

Les jeunes filles

Abandonnent leurs canaris

.

Sa vie

Est une vie

De solitude

Et de tristesse

.

Sans ami

Sans caresse

Nulle part

Où aller

.

Partout –

Etranger

.

Un crocodile

Crocodile

Végétarien

Et bon à rien

Qui a

Une sainte horreur

Du sang

.

S’il vous plaît

Ecrivez,

Ecrivez à:

Gentil Crocodile,

Baie Numéro 3,

Fleuve Niger.

. . .

Véronique Tadjo (born 1955, Paris/Abidjan, Ivory Coast)

“Crocodile”

.

It’s not easy to be a crocodile

Especially if you don’t want

To be a crocodile

The one you see

On the opposite page*

Is not happy

in his croc’s

Skin

He would have liked

To be different

He would have liked

To attract

Children

Play

with them

Talk

With their parents

Walk around

in the village

But, but, but

.

When he comes out

Of the water

Fisherman

Throw spears

Children

Take off

Young girls

Abandon their water jugs

.

His life

Is a life

Of solitude

And sadness

.

Without a friend

Without affection

Nowhere

To go

.

Everywhere

Strangers

.

A Crocodile

Vegetarian

Crocodile

And good for nothing

Who has

A holy horror

Of blood

.

Please

Write,

Write to:

Nice Crocodile,

Bay Number 3,

Niger River.

.

*The original French-language version of this poem featured a drawing by Tadjo herself of a crocodile.

. . . . .

Irene Rutherford McLeod: “Perro solitário” / “Lone Dog”

Posted: August 27, 2013 Filed under: English, Irene Rutherford McLeod, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Irene Rutherford McLeod: “Perro solitário” / “Lone Dog” ZP_Perro solitário_Las Playitas_Cuatro Ciénegas_Coahuila_México_fotógrafo Hector Garza

ZP_Perro solitário_Las Playitas_Cuatro Ciénegas_Coahuila_México_fotógrafo Hector Garza

.

Irene Rutherford McLeod (1891-1968)

“Perro solitário”

.

Soy un perro magro, un perro agudo – salvaje y solitário;

Un perro alborotador y firme, estoy cazando yo solo;

Un perro malo – y me cabreo – provocando a los tontos borregos;

Me gusta sentirme y aullar a la luna – para evitar que los almas gordas duerman.

.

Nunca ser un cachorro del regazo o lamer los pies sucios,

Un perrito dócil, elegante, arrastrándome por mi carne,

Ni la alfombrilla del hogar ni el plato bien llenado,

Sino puertas cerradas, piedras afiladas – y golpes, patadas: el odio.

.

Ningunos otros perros – para mí – corriendo hombro a hombro,

Algunos han corrido un rato corto – pero ningunos pueden durar.

El camino solo es mío – ¡Ah! – la senda ardua me parece bien:

¡Viento furioso, estrellas indómitas, el hambre de la búsqueda!

. . .

Irene Rutherford McLeod (1891-1968)

“Lone Dog”

.

I’m a lean dog, a keen dog, a wild dog, and lone;

I’m a rough dog, a tough dog, hunting on my own;

I’m a bad dog, a mad dog, teasing silly sheep;

I love to sit and bay the moon, to keep fat souls from sleep.

.

I’ll never be a lap dog, licking dirty feet,

A sleek dog, a meek dog, cringing for my meat,

Not for me the fireside, the well-filled plate,

But shut door, and sharp stone, and cuff and kick and hate.

.

Not for me the other dogs, running by my side,

Some have run a short while, but none of them would bide.

O mine is still the lone trail, the hard trail, the best –

Wide wind, and wild stars, and hunger of the quest!

.

Traducción del inglés al español / Translation from English into Spanish: Alexander Best

. . . . .

“Quien nace chicharra, muere cantando.”: ¡Las cigarras torontonienses hacen un gran zumbido! / “He who is born a cicada will die singing.”: Torontonian cicadas are right now making a big noise!

Posted: August 25, 2013 Filed under: English, Ernesto Cardenal, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on “Quien nace chicharra, muere cantando.”: ¡Las cigarras torontonienses hacen un gran zumbido! / “He who is born a cicada will die singing.”: Torontonian cicadas are right now making a big noise! ZP_Cicada from Borneo_© photographer Alex Hyde

ZP_Cicada from Borneo_© photographer Alex Hyde