Gregory Porter: “Somos pintados sobre un lienzo ” / “Painted on canvases”

Posted: August 14, 2013 Filed under: English, Gregory Porter, Spanish, Translator's Whimsy: Song Lyrics / Extravagancia del traductor: Letras de canciones traducidas por Alexander Best, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Gregory Porter: “Somos pintados sobre un lienzo ” / “Painted on canvases” ZP_Romare Bearden (1911-1988)_Morning of the Rooster_1980

ZP_Romare Bearden (1911-1988)_Morning of the Rooster_1980

.

Gregory Porter (Cantante/compositor de jazz, nacido en 1971, EE.UU.)

“Somos pintados sobre un lienzo ”

.

Somos como niños

Somos pintados sobre un lienzo

logrando los tonos mientras pasamos

Empezamos con el “gesso”

puesto con pinteles por la gente que conocemos

Sea esmerado con la técnica mientras avanza

Se aleja para admirar mi vista

¿Puedo usar los colores que yo elijo?

¿Tengo algo que decir sobre lo que usted usa?

¿Puedo conseguir colores verde y colores azul?

.

Somos hechos del pigmento de pintura que se aplica

Nuestras historias son dichos por nuestros tonos

Como Motley y Bearden

Estos maestros de la paz, de la vida,

Hay capas de colores, del tiempo

Se aleja para admirar mi vista

¿Puedo usar los colores que yo elijo?

¿Tengo algo que decir sobre lo que usted usa?

¿Puedo conseguir unos verde y unos azul?

.

Somos como niños

Somos pintados sobre una gama de lienzos…

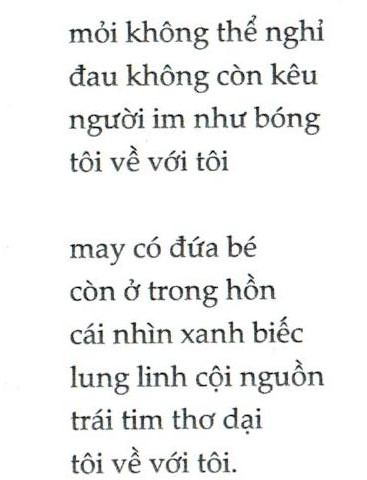

ZP_Archibald John Motley (1891-1981)_Self Portrait_1933

ZP_Archibald John Motley (1891-1981)_Self Portrait_1933

.

Gregory Porter (born 1971, American jazz vocalist/songwriter)

“Painted on canvases”

.

We are like children

we’re painted on canvases

picking up shades as we go

We start off with “gesso”

brushed on by people we know

Watch your technique as you go

Step back and admire my view

Can I use the colours I choose?

Do I have some say what you use?

Can I get some greens and some blues?

.

We’re made by the pigment of paint that is put upon

Our stories are told by our hues

Like Motley and Bearden

these masters of peace and life

layers of colours and time

Step back and admire my view

Can I use the colours I choose?

Do I have some say what you use?

Can I get some greens and some blues?

.

We are like children

We’re painted on canvases…

. . . . .

Maria Bethânia canta letras de Carlos Bahr & Adriana Calcanhotto / Maria Bethânia sings lyrics by Carlos Bahr & Adriana Calcanhotto

Posted: August 13, 2013 Filed under: English, Portuguese, Spanish, Translator's Whimsy: Song Lyrics / Extravagancia del traductor: Letras de canciones traducidas por Alexander Best, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Maria Bethânia canta letras de Carlos Bahr & Adriana Calcanhotto / Maria Bethânia sings lyrics by Carlos Bahr & Adriana Calcanhotto ZP_Maria Bethânia (born 1946), shown here at the age of 21, is a Brazilian singer and sister of Caetano Veloso

ZP_Maria Bethânia (born 1946), shown here at the age of 21, is a Brazilian singer and sister of Caetano Veloso

.

“Sin” / “Pecado”

Composer / Compositor: Carlos Bahr (Tango lyricist / Letrista de tango, 1902-1984, Buenos Aires, Argentina), with / con: Armando Pontier & Enrique Francini

As sung by / Cantada por: Maria Bethânia (from her album / de su álbum Pássaro Proibido, 1976)

.

I know not

whether this is forbidden;

if there’ll be forgiveness;

or if I’ll be carried to the brink of the abyss.

All that I know:

This is Love.

.

I know not

whether this Love is a sin;

if punishment awaits;

or if it disrespects all the decent laws

of humankind and of God.

.

All that I know: it’s a Love which stuns my Life

like a whirlwind; and

that I crawl, yes crawl, straight to your arms

in a blind passion.

.

And This is stronger than I am, than my Life,

my beliefs, my sense of duty.

It’s even stronger within me than

the fear of God.

.

Though it may be sin – how I want you,

yes, I want you all the same.

And even if everyone denies me that right,

I will seize hold of this Love.

. . .

Yo no sé

Si es prohibido

Si no tiene perdón

Si me lleva al abismo

Sólo se que es amor

.

Yo no sé

Si este amor es pecado

Si tiene castigo

Si es faltar a las leyes honradas

Del hombre y de Dios

.

Sólo sé que me aturde la vida

Como un torbellino

Que me arrastra y me arrastra a tus brazos

En ciega pasión

.

Es más fuerte que yo que mi vida

Mi credo y mi sino

Es más fuerte que todo el respeto

Y el temor a Dios

.

Aunque sea pecado te quiero

Te quiero lo mismo

Aunque todo me niegue el derecho

Me aferro a este amor.

. . .

“After having you” / “Depois de ter você ”

Composer / Composição: Adriana Calcanhotto (born in / nascida em 1965, Porto Alegre, Brasil)

As sung by / Cantada por: Maria Bethânia (from her album / em seu álbum Maricotinha, 2001)

.

After having you,

What reason is there to think of time,

how many hours have passed or remain?

If it’s night or if it’s warm out,

If we’re in summertime;

If the sun will show its face or not?

Or even what reason might a song like this serve?

After knowing you

– Poets? what’s the use of them?

Or of Gods – What purpose Doubts?

– Almond trees along the streets,

even the very streets themselves –

After having had You?

. . .

Depois de ter você,

Para que querer saber que horas são?

Se é noite ou faz calor,

Se estamos no verão,

Se o sol virá ou não,

Ou pra que é que serve uma canção como essa?

Depois de ter você, poetas para quê?

Os deuses, as dúvidas,

Para que amendoeiras pelas ruas?

Para que servem as ruas?

Depois de ter você.

. . .

Traducción/interpretación en inglés / Translation-interpretation from Spanish into English: Alexander Best

Tradução/interpretação em inglês / Translation-interpretation from Portuguese into English: Alexander Best

. . .

. . . . .

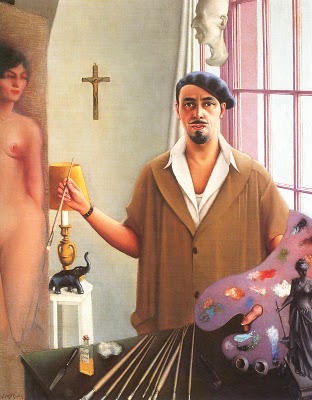

¿Eva, La Culpable? / Was IT All Eve’s Fault?

Posted: July 28, 2013 Filed under: English, Eva La Culpable...Was It All Eve's Fault?, Jee Leong Koh, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on ¿Eva, La Culpable? / Was IT All Eve’s Fault? ZP_El Adán reconsiderado…¡Piense en él dos veces!_Adam reconsidered…Give him a second thought!

ZP_El Adán reconsiderado…¡Piense en él dos veces!_Adam reconsidered…Give him a second thought!

.

“No Eva…Solo era una cantidad excesiva del Amor, su Culpa.”

(Aemilia Lanyer, poetisa inglés, 1569 – 1645, en su obra Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum: La Apología de Eva por La Mujer, 1611)

.

Jee Leong Koh

“Eva, La Culpable”

.

Aunque se ha ido del jardín, no se para de amarles…

Dios le convenció cuando sacó rápidamente de su manga planetaría

un ramo de luz. Miraron pasar el desfile de animales.

Le contó el chiste sobre el Arqueópterix, y se dio cuenta de

las plumas y las garras brutales – un poema – el primero de su tipo.

En una playa, alzado del océano con un grito, él entró en ella;

y ella, en olas onduladas, notó que el amor une y separa.

.

El serpiente fue un tipo más callado. Llegaba durante el otoño al caer la tarde,

viniendo a través de la hierba alta, y apenas sus pasos dividió las briznas.

Cada vez él le mostró una vereda diferente. Mientras que vagaban,

hablaron de la belleza de la luz golpeando en el árbol abedul;

el comportamiento raro de las hormigas; la manera más justa de

partir en dos una manzana.

Cuando apareció Adán, el serpiente se rindió a la felicidad la mujer Eva.

.

…Porque ella era feliz cuando encontró a Adán bajo del árbol de la Vida

– y aún está feliz – y Adán permanece como Adán: inarticulado, hombre de mala ortografía;

su cuerpo estando centrado precariamente en sus pies; firme en su mente que

Eva es la mujer pristina y que él es el hombre original. Necesitó a ella

y por eso rasguñó en el suelo – y creyó en el cuento de la costilla.

Eva necesitó a la necesidad de Adán – algo tan diferente de Dios y el Serpiente,

Y después de éso ella se encontró a sí misma afuera del jardín.

. . .

“Not Eve, whose Fault was only too much Love.”

(Aemilia Lanyer, English poetess, 1569 – 1645, in Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum: Eve’s Apologie in Defence of Women, 1611)

.

Jee Leong Koh

“Eve’s Fault”

.

Though she has left the garden, she does not stop loving them.

God won her when he whipped out from his planetary sleeve

a bouquet of light. They watched the parade of animals pass.

He told her the joke about the Archaeopteryx, and she noted

the feathers and the killing claws, a poem, the first of its kind.

On a beach, raised from the ocean with a shout, he entered her

and she realized, in rolling waves, that love joins and separates.

.

The snake was a quieter fellow. He came in the fall evenings

through the long grass, his steps barely parting the blades.

Each time he showed her a different path. As they wandered,

they talked about the beauty of the light striking the birch,

the odd behavior of the ants, the fairest way to split an apple.

When Adam appeared, the serpent gave her up to happiness.

.

For happy she was when she met Adam under the tree of life,

still is, and Adam is still Adam, inarticulate, a terrible speller,

his body precariously balanced on his feet, his mind made up

that she is the first woman and he the first man. He needed

her and so scratched down and believed the story of the rib.

She needed Adam’s need, so different from God and the snake

– and that was when she discovered herself outside the garden.

. . . . .

Jee Leong Koh nació en Singapur y vive en Nueva York. Es profesor, también autor de cuatro poemarios.

Jee Leong Koh was born in Singapore and now lives in New York City where he is a teacher.

He is the author of four poetry collections: Payday Loans, Equal to the Earth, Seven Studies for a Self Portrait and The Pillow Book.

. . .

Traducción en español / Translation into Spanish: Alexander Best

. . . . .

Alootook Ipellie: Artist, Writer, Dreamer !

Posted: April 11, 2013 Filed under: Alootook Ipellie, English, Writer-Artist-Dreamer: Alootook Ipellie Comments Off on Alootook Ipellie: Artist, Writer, Dreamer !

ZP_The agony and the ecstasy_illustration for a short story in Arctic Dreams and Nightmares_Alootook Ipellie, 1993

Alootook Ipellie (1951-2007)

“It Was Not ‘Jajai-ja-jiijaaa‘ Anymore – But ‘Amen’”

.

It was in the guise of the Holy Spirit

That they swooped down on the tundra

Single-minded and determined

To change forever the face

Of ancient Spirituals

These lawless missionaries from places unknown

Became part of the landscape

Which was once the most sacred tomb

Of lives lived long ago

The last connection to the ancient Spirits

Of the most sacred land

Would be slowly severed

Never again to be sensed

Never again to be felt

Never again to be seen

Never again to be heard

Never again to be experienced

Sadness supreme for the ancient culture

Jubilation in the hearts of the converters

Where was justice to be found?

They said it was in salvation

From eternal fire

In life after death

And unto everlasting Life in Heaven

A simple life lived

On the sacred land was no more

The psalm book now replaced

The sacred songs of shamans

The Lord’s Prayer now ruled

Over the haunting chant of revival

It was not ‘Jajai-ja-jiijaaa’ anymore

But-

‘Amen’

. . .

“How noisy they seem”

.

I saw a picture today, in the pages of a book.

It spoke of many memories of when I was still a child:

Snow covered the ground,

And the rocky hills were cold and gray with frost.

The sun was shining from the west,

And the shadows were dark against the whiteness of the

Hardened snow.

.

My body felt a chill

Looking at two Inuit boys playing with their sleigh,

For the fur of their hoods was frosted under their chins,

From their breathing.

In the distance, I could see at least three dog teams going away,

But I didn’t know where they were going,

For it was only a photo.

I thought to myself that they were probably going hunting,

To where they would surely find some seals basking on the ice.

Seeing these things made me feel good inside,

And I was happy that I could still see the hidden beauty of the land,

And know the feeling of silence.

. . .

“Walking Both Sides of an Invisible Border”

.

It is never easy

Walking with an invisible border

Separating my left and right foot

I feel like an illegitimate child

Forsaken by my parents

At least I can claim innocence

Since I did not ask to come

Into this world

Walking on both sides of this

Invisible border

Each and everyday

And for the rest of my life

Is like having been

Sentenced to a torture chamber

Without having committed a crime

Understanding the history of humanity

I am not the least surprised

This is happening to me

A non-entity

During this population explosion

In a minuscule world

I did not ask to be born an Inuk

Nor did I ask to be forced

To learn an alien culture

With its alien language

But I lucked out on fate

Which I am unable to undo

I have resorted to fancy dancing

In order to survive each day

No wonder I have earned

The dubious reputation of being

The world’s premier choreographer

Of distinctive dance steps

That allow me to avoid

Potential personal paranoia

On both sides of this invisible border

Sometimes the border becomes so wide

That I am unable to take another step

My feet being too far apart

When my crotch begins to tear

I am forced to invent

A brand new dance step

The premier choreographer

Saving the day once more

Destiny acted itself out

Deciding for me where I would come from

And what I would become

So I am left to fend for myself

Walking in two different worlds

Trying my best to make sense

Of two opposing cultures

Which are unable to integrate

Lest they swallow one another whole

Each and everyday

Is a fighting day

A war of raw nerves

And to show for my efforts

I have a fair share of wins and losses

When will all this end

This senseless battle

Between my left and right foot

When will the invisible border

Cease to be.

.

(1996)

. . . . .

Alootook Ipellie

“Self-Portrait: Inverse Ten Commandments” (1993)

.

I woke up snuggled in the warmth of a caribou-skin blanket during a vicious storm. The wind was howling like a mad dog, whistling whenever it hit a chink in my igloo. I was exhausted from a long, hard day of sledding with my dogteam on one of the roughest terrains I had yet encountered on this particular trip.

.

I tried going back to sleep, but the wind kept waking me as it got stronger and even louder. I resigned myself to just lying there in the moonless night, eyes open, looking into the dense darkness. I felt as if I was inside a black hole somewhere in the universe. It didn’t seem to make any difference whether my eyes were opened or closed.

.

The pitch darkness and the whistling wind began playing games with my equilibrium. I seemed to be going in and out of consciousness, not knowing whether I was still wide awake or had gone back to sleep. I also felt weightless, as if I had been sucked in by a whirlwind vortex.

.

My conscious mind failed me when an image of a man’s face appeared in front of me. What was I to make of his stony stare – his piercing eyes coloured like a snowy owl’s, and bloodshot, like that of a walrus?

.

He drew his clenched fists in front of me. Then, one by one, starting with the thumbs, he spread out his fingers. Each finger and thumb revealed a tiny, agonized face, with protruding eyes moving snake-like, slithering in and out of their sockets! Their tongues wagged like tails, trying to say something, but only mumbled, since they were sticking too far out of their mouths to be legible. The pitch of their collective squeal became higher and higher and I had to cover my ears to prevent my eardrums from being punctured. When the high pitched squeal became unbearable, I screamed like a tortured man.

.

I reached out frantically with both hands to muffle the squalid mouths. Just moments before I grabbed them, they faded into thin air, reappearing immediately when I drew my hands back.

.

Then there was perfect silence.

I looked at the face, studying its features more closely, trying to figure out who it was. To my astonishment, I realized the face was that of a man I knew well. The devilish face, with its eyes planted upside down, was really some form of an incarnation of myself! This realization threw me into a psychological spin.

.

What did this all mean? Did the positioning of his eyes indicate my devilish image saw everything upside down? Why the panic-stricken faces on the tips of his thumbs and fingers? Why were they in such fits of agony? Had I indeed arrived at Hell’s front door and Satan had answered my call?

.

The crimson sheen reflecting from his jet-black hair convinced me I had arrived at the birthplace of all human fears. His satanic eyes were so intense that I could not look away from them even though I tried. They pulled my mind into a hypnotic state. After some moments, communicating through telepathy, the image began telling me horrific tales of unfortunate souls experiencing apocalyptic terror in Hell’s Garden of Nede.

.

The only way I could deal with this supernatural experience was to fight to retain my sanity, as fear began overwhelming me. I knew it would be impossible for me to return to the natural, physical world if I did not fight back.

.

This experience made my memory flash back to the priestly eyes of our local minister of Christianity. He had told us how all human beings, after their physical death, were bound by the doctrine of the Christian Church that they would be sent to either Heaven or Hell. The so-called Christian minister had led me to believe that if I retained my good-humoured personality toward all mankind, I would be assured a place in God’s Heaven. But here I was, literally shrivelling in front of an image of myself as Satan incarnate!

.

I couldn’t quite believe what my mind telepathically heard next from this devilish man. As it turned out, the ten squalid heads represented the Inverse Ten Commandments in Hell’s Garden of Nede. To reinforce this, the little mouths immediately began squealing acidic shrills. They finally managed to make sense with the motion of their wagging tongues. Two words sprang out thrice from ten mouths in unison: “Thou Shalt! Thou Shalt! Thou Shalt!” I could not believe I was hearing those two words. Why was I the object of Satan’s wrath? Had I been condemned to Hell’s Hole?

.

My mind flashed back to the solemn interior of our local church once more where these words had been spoken by the minister: “God made man in His own image.” In which case, the Satan could also have made man in his own image. So I was almost sure that I was face to face with my own image as the Satan of Hell!

.

“Welcome, welcome, welcome,” the image said, his hands reaching for mine. “Welcome to the Garden of Nede.”

.

I found his greeting repulsive, more so when he wrapped his squalid fingertips around my hands. The slithering eyes retreated into their sockets, closing their eyelids. The wagging tongues began slurping and licking my hands like hungry tundra wolves. I pulled my hands away as hard as I could but wasn’t able to budge them.

.

The rapid motion of their sharp tongues cut through my skin. The cruelty inflicted on me was unbearable! Blood was splattering all over my face and body. I screamed in dire pain. As if by divine intervention, I instinctively looked down between the legs of my Satanic image. I bolted my right knee upward as hard as I could muster toward his triple bulge. My human missile hit its target, instantly freeing my hands. In the same violent moment, the image of myself as the Satan of Hell’s Garden of Nede disappeared into thin air. Only a wispy odour of burned flesh remained.

.

Pitch darkness once again descended all around. Total silence. Calm. Then, peace of mind…

.

Some days later, when I had arrived back in my camp, I was able to analyze what I had experienced that night. As it turned out, my soul had gone through time and space to visit the dark side of myself as the Satan incarnate. My soul had gone out to scout my safe passage to the cosmos. The only way any soul is freed is for it to get rid of its Satan incarnate at the doorstep of Hell’s Garden of Nede. If my soul had not done what it did, it would have remained mired in Hell’s Garden of Nede for an eternity after my physical death. This was a revelation that I did not quite know how to deal with. But it was an essential element of my successful passage to the cosmos as a soul and therefore, the secret to my happiness in afterlife!

When Inuk illustrator and writer Alootook Ipellie died of heart attack at the age of 56 in 2007 he had only just unveiled a series of new drawings at an Ottawa exhibition – this, after a decade of artistic silence. Paul Gessell of The Ottawa Citizen wrote: “Ipellie’s technical skills are unbeatable. His content ranges from playfully innocent to devilishly searing. These pen-and-ink drawings, although often minimal, carry a wallop.”

Born in 1951 to Napatchie and Joanassie at a nomadic hunting camp on Baffin Island, Ipellie’s family moved to Frobisher Bay (later Iqaluit) when Alootook was a little boy. As an adult the shy and thoughtful Ipellie lived in Ottawa for most of his life, and that was where he completed high school in the late 1960s. Although he enrolled in a lithography course at West Baffin Co-op, he dropped out of it in 1972 and took a job as both typist and translator for Inuit Today magazine. He also began to do one-box cartoons for the magazine, commenting on social issues with a wry humour that Inuit readers appreciated. He would wear many hats at Inuit Today, eventually becoming editor. In the early 1990s he drew a popular comic called “Nuna and Vut” for Nunatsiaq newspaper where he also penned a column called “Ipellie’s Shadow”.

Not one to travel – although he did plan to return to Nunavut in 2008, having grown tired of southern life – still, Ipellie had ventured as far as Germany and Australia to tour with his pen-and-ink drawings which were slowly gaining recognition – slowly very slowly, because the art collectors’ preference continues to be for the beautiful bird images of Kenojuak Ashevak (bless her!) over those of Annie Pootoogook – where the here-and-now ‘real-ness’ factor is paramount.

A poet and short-story writer as well, Ipellie explored a vividly creative imagination in his 1993 story-book with illustrations: Arctic Dreams and Nightmares.

In the preface he wrote: “This is a story of an Inuk who has been dead for a thousand years and who then recalls the events of his former life through the eyes of his living soul. It’s also a story about a powerful shaman who learned his shamanic trade as an ordinary Inuk. He was determined to overcome his personal weaknesses, first by dealing with his own mind and, then, with the forces out of his reach or control.”

In Arctic Dreams and Nightmares bawdy humour and frank descriptions of sex and violence give Ipellie’s stories much in common with the Inuit people’s stories from olden times. Ipellie writes of his main character’s encounter with his Satanic other self; of his crucifixion, too, complete with hungry wolves; of Sedna, the Inuit Mother of Sea Beasts’ sexual frustration and how shamans came up with a plan to help satisfy Her so that she would release walrus and seal once again for the starving ice fishermen and their families; a hermaphrodite shaman who is executed via harpoon plus bow-and-arrow; and a sealskin blanket-toss game for the purpose of throwing a man all the way up to ‘heaven’.

Alootook Ipellie’s perspective on his life as an Inuk was this:

“In some ways, I think I am fortunate to have been part and parcel of an era when cultural change pointed its ugly head to so many Inuit who eventually became victims of this transitional change. It is to our credit that, as a distinct culture, we have kept our eyes and intuition on both sides of the cultural tide, aspiring, as always, to win the battle as well as the war. Today, we are still mired in the battle but the war is finally ending.”

.

We thank John Thompson of the Iqaluit weekly Nunatsiaq News for biographical details of Alootook Ipellie’s life.

. . . . .

Mi’kmaw I am: Poems of Rita Joe + We are the Dreamers

Posted: April 11, 2013 Filed under: English, Mi'kmaq / Míkmawísimk, Mi'kmaw I am: Poems of Rita Joe + We are the Dreamers, Rita Joe Comments Off on Mi’kmaw I am: Poems of Rita Joe + We are the DreamersRita Joe

(Mi’kmaw poet, 1932-2007, Whycocomagh, Nova Scotia, Canada)

.

“A Mi’kmaw Cure-All for Ingrown Toenail”

.

I have a comical story for ingrown toenail

I want to share with everybody.

The person I love and admire is a friend.

This is her cure-all for an elderly problem.

She bought rubber boots one size larger

And put salted water above the toe

Then wore the boots all day.

When evening came they cut easy,

The ingrown problem much better.

I laughed when I heard the story.

It is because I have the same tender distress

So might try the Mi’kmaw cure-all.

The boots are there, just add the salted water

And laugh away the pesky sore.

I’m even thinking of bottling for later use.

. . .

“Street Names”

.

In Eskasoni there were never any street names, just name areas.

There was Qam’sipuk (Across The River),

74th Street now, you guess why the name.

Apamuek, central part of Eskasoni, the home of Apamu.

New York Corner, never knew the reason for the name.

There is Gabriel Street, the church Gabriel Centre.

Espise’k, Very Deep Water.

Beach Road, naturally the beach road.

Mickey’s Lane. There must be a Mickey there.

Spencer’s Lane, Spencer lives there, why not Arlene? His wife.

Cremo’s Lane, the last name of many people.

Crane Cove Road, the location of Crane Cove Fisheries.

Pine Lane, a beautiful spot, like everywhere else in Eskasoni.

Silverwood Lane, the place of silverwood.

George Street, bet you can’t guess who lives there.

Denny’s Lane, the last name of many Dennys.

Paul’s Lane, there are many Pauls, Poqqatla’naq.

Johnson Place, many Johnsons.

Morris Lane, guess who?

Horseshoe Drive, considering no horses in Eskasoni.

Beacon Hill, elegant place name,

I used to work at Beacon Hill Hospital in Boston.

Mountain Road,

A’nslm Road, my son-in-law Tom Sylliboy, daughter,

three grandchildren live there,

and Lisa Marie, their poodle.

Apamuekewawti, near where I live, come visit.

. . .

“Ankita’si (I think)”

.

A thought is to catch an idea

Between two minds.

Swinging to and fro

From English to Native,

Which one will I create, fulfill

Which one to roll along until arriving

To settle, still.

.

I know, my mind says to me

I know, try Mi’kmaw…

Ankite’tm

Na kelu’lk we’jitu (I find beauty)

Ankite’tm

Me’ we’jitutes (I will find more)

Ankita’si me’ (I think some more)

.

We’jitu na!*

.

*We’jitu na! – I find!

. . .

“Plawej and L’nui’site’w” (Partridge and Indian-Speaking Priest)

.

Once there was an Indian-speaking priest

Who learned Mi’kmaw from his flock.

He spoke the language the best he knew how

But sometimes got stuck.

They called him L’nui’site’w out of respect to him

And loving the man, he meant a lot to them.

At specific times he heard their confessions

They followed the rules, walking to the little church.

A widow woman was strolling through the village

On her way there, when one hunter gave her a day-old plawej

She took the partridge, putting it inside her coat

Thanking the couple, going her way.

At confession, the priest asked, “What is the smell?”

In Mi’kmaw she said, “My plawej.”

He gave blessing and sent her on her way.

The next day he gave a long sermon, ending with the words

“Keep up the good lives you are leading,

but wash your plawejk.”

The women giggled, he never knew why.

To this day there is a saying, they laugh and cry.

Whatever you do, wherever you go,

Always wash your plawejk.

. . .

“I Washed His Feet”

.

In early morning she burst into my kitchen. “I got something to

tell you, I was disrespectful to him,” she said. “Who were you

disrespectful to?” I asked. “Se’sus*,” she said. I was overwhelmed

by her statement. Caroline is my second youngest.

How in the world can one be disrespectful to someone we

never see? It was in a dream, there were three knocks on the

door. I opened the door, “Oh my God you’re here.” He came in

but stood against the wall. “I do not want to track dirt on your

floor,” he said. I told him not to mind the floor but come in, that

tea and lu’sknikn (bannock) will be ready in a moment. He ate and

thanked me… But then he asked if I would wash his feet, he

looked kind and normal, but a bit tired. In the dream, she said, I

took an old t-shirt and wet it with warm water and washed his

feet, carefully cleaning them, especially between his toes. I

wiped them off and put his sandals back on. After I was finished

I put the TV on, he leaned forward looking at the television.

His hair fell forward, he pushed it away from his face. I

removed a tendril away from his eye. “I am tired of my hair,”

he said. “Why don’t you wear a ponytail or have it braided?”

He said all right but asked me to teach him how to braid. I

stood beside him and touched his soft hair and saw a tear in

his eye, using my pinky finger to wipe the tear away. He smiled

gently. I then showed him how to braid his hair, guiding his

hands on how it was done. He caught on real easy. He was

happy. He thanked me for everything. You are welcome any

time you want to visit. He smiled as he walked out. He is just

showing us he is around at any time, even in 1997.

I was honoured to hear the story firsthand.

.

* Se’sus – Jesus

. . .

“Apiksiktuaqn (To forgive, be forgiven)”

.

A friend of mine in Eskasoni Reservation

Entered the woods and fasted for eight days.

I awaited the eight days to see him

I wanted to know what he learned from the sune’wit.

To my mind this is the ultimate for a cause

Learning the ways, an open door, derive.

At the time he did it, it was for

The people, the oncoming pow-wow

The journey to know, rationalize, spiritual growth.

When he drew near, a feeling like a parent on me

He was my son, I wanted to listen.

He talked fast, at times with a rush of words

As if to relate all, but sadness took over.

I hugged him and said, “Don’t talk if it is too sad.”

The spell was broken, he could say no more.

The one thing I heard him say, “Apiksiktuaqn nuta’ykw”,

For months it stayed on my mind.

Now it may go away as I write

Because this is the past, the present, the future.

.

I wish this would happen to all of us

Unity then will be the world over

My friend carried a message

Let us listen.

.

sune’wit – to fast, abstain from food

Apiksiktuaqn nuta’ykw – To forgive, be forgiven.

.

All of the above poems – from Rita Joe’s 1999 collection We are the Dreamers,

(published by Breton Books, Wreck Cove, Nova Scotia)

. . . . .

The following is a selection from the 26 numbered poems of Poems of Rita Joe

(published in 1978 by Abanaki Press, Halifax, Nova Scotia)

.

6

.

Wen net ki’l?

Pipanimit nuji-kina’muet ta’n jipalk.

Netakei, aq i’-naqawey;

Koqoey?

.

Ktikik nuji-kina’masultite’wk kimelmultijik.

Na epas’si, taqawajitutm,

Aq elui’tmasi

Na na’kwek.

.

Espi-kjijiteketes,

Ma’jipajita’siw.

Espitutmikewey kina’matneweyiktuk eyk,

Aq kinua’tuates pa’ qlaiwaqnn ni’n nikmaq.

.

Who are you?

Question from a teacher feared.

Blushing, I stammered

What?

.

Other students tittered.

I sat down forlorn, dejected,

And made a vow

That day

.

To be great in all learnings,

No more uncertain.

My pride lives in my education,

And I will relate wonders to my people.

. . .

10

.

Ai! Mu knu’kwaqnn,

Mu nuji-wi’kikaqnn,

Mu weskitaqawikasinukul kisna

mikekni-napuikasinukul

Kekinua’tuenukul wlakue’l

pa’qalaiwaqnn.

.

Ta’n teluji-mtua’lukwi’tij nuji-

kina’mua’tijik a.

.

Ke’ kwilmi’tij,

Maqamikewe’l wisunn,

Apaqte’l wisunn,

Sipu’l;

Mukk kas’tu mikuite’tmaqnmk

Ula knu’kwaqnn.

.

Ki’ welaptimikl

Kmtne’l samqwann nisitk,

Kesikawitkl sipu’l.

Ula na kis-napui’kmu’kl

Mikuite’tmaqanminaq.

Nuji-kina’masultioq,

we’jitutoqsip ta’n kisite’tmekl

Wisunn aq ta’n pa’-qi-klu’lk,

Tepqatmi’tij L’nu weja’tekemk

weji-nsituita’timk.

.

Aye! no monuments,

No literature,

No scrolls or canvas-drawn pictures

Relate the wonders of our yesterday.

.

How frustrated the searchings

of the educators.

.

Let them find

Land names,

Titles of seas,

Rivers;

Wipe them not from memory.

These are our monuments.

.

Breathtaking views –

Waterfalls on a mountain,

Fast flowing rivers.

These are our sketches

Committed to our memory.

Scholars, you will find our art

In names and scenery,

Betrothed to the Indian

since time began.

. . .

14

.

Kiknu na ula maqmikew

Ta’n asoqmisk wju’sn kmtnji’jl

Aq wastewik maqmikew

Aq tekik wju’sn.

.

Kesatm na telite’tm L’nueymk,

Paqlite’tm, mu kelninukw koqoey;

Aq ankamkik kloqoejk

Wejkwakitmui’tij klusuaqn.

Nemitaq ekil na tepknuset tekik wsiskw

Elapekismatl wta’piml samqwan-iktuk.

.

Teli-ankamkuk

Nkutey nike’ kinu tepknuset

Wej-wskwijnuulti’kw,

Pawikuti’kw,

Tujiw keska’ykw, tujiw apaji-ne’ita’ykw

Kutey nike’ mu pessipketenukek

iapjiweyey.

.

Mimajuaqnminu siawiaq

Mi’soqo kikisu’a’ti’kw aq nestuo’lti’kw.

Na nuku’ kaqiaq.

Mu na nuku’eimukkw,

Pasik naqtimu’k

L’nu’ qamiksuti ta’n mu nepknukw.

.

Our home is in this country

Across the windswept hills

With snow on fields.

The cold air.

.

I like to think of our native life,

Curious, free;

And look at the stars

Sending icy messages.

My eyes see the cold face of the moon

Cast his net over the bay.

.

It seems

We are like the moon –

Born,

Grow slowly,

Then fade away, to reappear again

In a never-ending cycle.

.

Our lives go on

Until we are old and wise.

Then end.

We are no more,

Except we leave

A heritage that never dies.

. . .

19

.

Klusuaqnn mu nuku’ nuta’nukul

Tetpaqi-nsitasin.

Mimkwatasik koqoey wettaqne’wasik

L’nueyey iktuk ta’n keska’q

Mu a’tukwaqn eytnukw klusuaqney

panaknutk pewatmikewey

Ta’n teli-kjijituekip seyeimik

.

Espe’k L’nu’qamiksuti,

Kelo’tmuinamitt ajipjitasuti.

Apoqnmui kwilm nsituowey

Ewikasik ntinink,

Apoqnmui kaqma’si;

Pitoqsi aq melkiknay.

.

Mi’kmaw na ni’n;

Mukk skmatmu piluey koqoey wja’tuin.

.

Words no longer need

Clear meanings.

Hidden things proceed from a lost legacy.

No tale in words bares our desire, hunger,

The freedom we have known.

.

A heritage of honour

Sustains our hopes.

Help me search the meaning

Written in my life,

Help me stand again

Tall and mighty.

.

Mi’kmaw I am;

Expect nothing else from me.

Rita Joe, born Rita Bernard in 1932, was a poet, a writer, and a human rights activist. Born in Whycocomagh, Nova Scotia, Canada, she was raised in foster homes after being orphaned in 1942. She was educated at Shubenacadie Residential School where she learned English – and that experience was also the impetus for writing a good number of her poems. (“I Lost My Talk” is about having her Mi’kmaq language denied at school.) While identity-erasure was part of her Canadian upbringing, still she managed in her writing – and in her direct, in-person activism – to promote compassion and cooperation between Peoples. Rita married Frank Joe in 1954 and together they raised ten children at their home in The Eskasoni First Nation, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. It was in her thirties, in the 1960s, that Joe began to write poetry so as to counteract the negative images of Native peoples found in the books that her children read. The Poems of Rita Joe, from 1978, was the first published book of Mi’kmaq poetry by a Mi’kmaw author. Rita Joe died in 2007, at the age of 75, after struggling with Parkinson’s Disease. Her daughters found a revision of her last poem “October Song” on her typewriter. The poem reads: “On the day I am blue, I go again to the wood where the tree is swaying, arms touching you like a friend, and the sound of the wind so alone like I am; whispers here, whispers there, come and just be my friend.”

. . . . .

Pauline Johnson / “Tekahionwake”: “Let her be natural”

Posted: April 11, 2013 Filed under: English, Pauline Johnson, Pauline Johnson's "Flint & Feather" Comments Off on Pauline Johnson / “Tekahionwake”: “Let her be natural”

ZP_E. Pauline Johnson gathered together her complete poems, though others have since been discovered, for publication in 1912, the year before her death. In her Author’s Forward to Flint and Feather she writes: This collection of verse I have named Flint and Feather because of the association of ideas. Flint suggests the Red man’s weapons of war, it is the arrow tip, the heart-quality of mine own people, let it therefore apply to those poems that touch upon Indian life and love. The lyrical verse herein is as a Skyward floating feather, Sailing on summer air. And yet that feather may be the eagle plume that crests the head of a warrior chief; so both flint and feather bear the hall-mark of my Mohawk blood._Book jacket shown here is from a 1930s edition of Flint and Feather.

Pauline Johnson / “Tekahionwake”

(1861 – 1913, born at Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation, Ontario, Canada)

.

“The Cattle Thief”

.

They were coming across the prairie, they were

galloping hard and fast;

For the eyes of those desperate riders had sighted

their man at last –

Sighted him off to Eastward, where the Cree

encampment lay,

Where the cotton woods fringed the river, miles and

miles away.

Mistake him? Never! Mistake him? the famous

Eagle Chief!

That terror to all the settlers, that desperate Cattle

Thief –

That monstrous, fearless Indian, who lorded it over

the plain,

Who thieved and raided, and scouted, who rode like

a hurricane!

But they’ve tracked him across the prairie; they’ve

followed him hard and fast;

For those desperate English settlers have sighted

their man at last.

.

Up they wheeled to the tepees, all their British

blood aflame,

Bent on bullets and bloodshed, bent on bringing

down their game;

But they searched in vain for the Cattle Thief: that

lion had left his lair,

And they cursed like a troop of demons – for the women

alone were there.

“The sneaking Indian coward,” they hissed; “he

hides while yet he can;

He’ll come in the night for cattle, but he’s scared

to face a man.”

“Never!” and up from the cotton woods rang the

voice of Eagle Chief;

And right out into the open stepped, unarmed, the

Cattle Thief.

Was that the game they had coveted? Scarce fifty

years had rolled

Over that fleshless, hungry frame, starved to the

bone and old;

Over that wrinkled, tawny skin, unfed by the

warmth of blood.

Over those hungry, hollow eyes that glared for the

sight of food.

.

He turned, like a hunted lion: “I know not fear,”

said he;

And the words outleapt from his shrunken lips in

the language of the Cree.

“I’ll fight you, white-skins, one by one, till I

kill you all,” he said;

But the threat was scarcely uttered, ere a dozen

balls of lead

Whizzed through the air about him like a shower

of metal rain,

And the gaunt old Indian Cattle Thief dropped

dead on the open plain.

And that band of cursing settlers gave one

triumphant yell,

And rushed like a pack of demons on the body that

writhed and fell.

“Cut the fiend up into inches, throw his carcass

on the plain;

Let the wolves eat the cursed Indian, he’d have

treated us the same.”

A dozen hands responded, a dozen knives gleamed

high,

But the first stroke was arrested by a woman’s

strange, wild cry.

And out into the open, with a courage past

belief,

She dashed, and spread her blanket o’er the corpse

of the Cattle Thief;

And the words outleapt from her shrunken lips in

the language of the Cree,

“If you mean to touch that body, you must cut

your way through me.”

And that band of cursing settlers dropped

backward one by one,

For they knew that an Indian woman roused, was

a woman to let alone.

And then she raved in a frenzy that they scarcely

understood,

Raved of the wrongs she had suffered since her

earliest babyhood:

“Stand back, stand back, you white-skins, touch

that dead man to your shame;

You have stolen my father’s spirit, but his body I

only claim.

You have killed him, but you shall not dare to

touch him now he’s dead.

You have cursed, and called him a Cattle Thief,

though you robbed him first of bread –

Robbed him and robbed my people – look there, at

that shrunken face,

Starved with a hollow hunger, we owe to you and

your race.

What have you left to us of land, what have you

left of game,

What have you brought but evil, and curses since

you came?

How have you paid us for our game? how paid us

for our land?

By a book, to save our souls from the sins you

brought in your other hand.

Go back with your new religion, we never have

understood

Your robbing an Indian’s body, and mocking his

soul with food.

Go back with your new religion, and find – if find

you can –

The honest man you have ever made from out a

starving man.

You say your cattle are not ours, your meat is not

our meat;

When you pay for the land you live in, we’ll pay

for the meat we eat.

Give back our land and our country, give back our

herds of game;

Give back the furs and the forests that were ours

before you came;

Give back the peace and the plenty. Then come

with your new belief,

And blame, if you dare, the hunger that drove him to

be a thief.”

. . .

“A Cry from an Indian Wife” (1885)

.

My forest brave, my Red-skin love, farewell;

We may not meet to-morrow; who can tell

What mighty ills befall our little band,

Or what you’ll suffer from the white man’s hand?

Here is your knife! I thought ’twas sheathed for aye.

No roaming bison calls for it to-day;

No hide of prairie cattle will it maim;

The plains are bare, it seeks a nobler game:

‘Twill drink the life-blood of a soldier host.

Go; rise and strike, no matter what the cost.

Yet stay. Revolt not at the Union Jack,

Nor raise Thy hand against this stripling pack

Of white-faced warriors, marching West to quell

Our fallen tribe that rises to rebel.

They all are young and beautiful and good;

Curse to the war that drinks their harmless blood.

Curse to the fate that brought them from the East

To be our chiefs – to make our nation least

That breathes the air of this vast continent.

Still their new rule and council is well meant.

They but forget we Indians owned the land

From ocean unto ocean; that they stand

Upon a soil that centuries agone

Was our sole kingdom and our right alone.

They never think how they would feel to-day,

If some great nation came from far away,

Wresting their country from their hapless braves,

Giving what they gave us – but wars and graves.

Then go and strike for liberty and life,

And bring back honour to your Indian wife.

Your wife? Ah, what of that, who cares for me?

Who pities my poor love and agony?

What white-robed priest prays for your safety here,

As prayer is said for every volunteer

That swells the ranks that Canada sends out?

Who prays for vict’ry for the Indian scout?

Who prays for our poor nation lying low?

None – therefore take your tomahawk and go.

My heart may break and burn into its core,

But I am strong to bid you go to war.

Yet stay, my heart is not the only one

That grieves the loss of husband and of son;

Think of the mothers o’er the inland seas;

Think of the pale-faced maiden on her knees;

One pleads her God to guard some sweet-faced child

That marches on toward the North-West wild.

The other prays to shield her love from harm,

To strengthen his young, proud uplifted arm.

Ah, how her white face quivers thus to think,

Your tomahawk his life’s best blood will drink.

She never thinks of my wild aching breast,

Nor prays for your dark face and eagle crest

Endangered by a thousand rifle balls,

My heart the target if my warrior falls.

O! coward self I hesitate no more;

Go forth, and win the glories of the war.

Go forth, nor bend to greed of white men’s hands,

By right, by birth we Indians own these lands,

Though starved, crushed, plundered, lies our nation low…

Perhaps the white man’s God has willed it so.

.

Editor’s note: “the war” referred to in Johnson’s poem is The NorthWest Rebellion (or NorthWest Resistance) of 1885, led by Louis Riel.

. . .

“The Wolf”

.

Like a grey shadow lurking in the light,

He ventures forth along the edge of night;

With silent foot he scouts the coulie’s rim

And scents the carrion awaiting him.

His savage eyeballs lurid with a flare

Seen but in unfed beasts which leave their lair

To wrangle with their fellows for a meal

Of bones ill-covered. Sets he forth to steal,

To search and snarl and forage hungrily;

A worthless prairie vagabond is he.

Luckless the settler’s heifer which astray

Falls to his fangs and violence a prey;

Useless her blatant calling when his teeth

Are fast upon her quivering flank–beneath

His fell voracity she falls and dies

With inarticulate and piteous cries,

Unheard, unheeded in the barren waste,

To be devoured with savage greed and haste.

Up the horizon once again he prowls

And far across its desolation howls;

Sneaking and satisfied his lair he gains

And leaves her bones to bleach upon the plains.

. . .

“The Indian Corn Planter”

.

He needs must leave the trapping and the chase,

For mating game his arrows ne’er despoil,

And from the hunter’s heaven turn his face,

To wring some promise from the dormant soil.

.

He needs must leave the lodge that wintered him,

The enervating fires, the blanket bed–

The women’s dulcet voices, for the grim

Realities of labouring for bread.

.

So goes he forth beneath the planter’s moon

With sack of seed that pledges large increase,

His simple pagan faith knows night and noon,

Heat, cold, seedtime and harvest shall not cease.

.

And yielding to his needs, this honest sod,

Brown as the hand that tills it, moist with rain,

Teeming with ripe fulfilment, true as God,

With fostering richness, mothers every grain.

. . .

Emily Pauline Johnson (1861 – 1913) took on the Mohawk-language name Tekahionwake (meaning “double life”) around the time, as a young adult, she became aware of her ability not only as a woman who was writing poetry but also as a performer. Words such as transgressive and performativity – belovéd of academics in the 21st century – were words she mightn’t have known yet she “enacted” their meanings – and without the cadre of professionals to chatter about “who she really was”. And who was she – really? Well, she was complex – in some ways uncategorizable. A young woman who helped to support her widowed mother (her father, Brantford Six Nations Chief George Henry Martin Johnson (Onwanonsyshon) died in 1884) via the publication of her sentimental-exotic yet oddly-truthful poems; whose attachment to her father’s Native-ness was deeply felt during the onset of the Erasure Period chapter in First-Nations history in that New Nation – Canada. Pauline Johnson was mixed-race – Mohawk father of chieftain lineage, mother (Emily Susana Howells), a kind of English “rose” in a young British-colonial country. Enamoured of The Song of Hiawatha, and of Wacousta – Pauline was yet entranced by and deeply listened to the Native oral histories of John Smoke Johnson, her paternal grandfather. This was Pauline Johnson.

From about 1892 until 1909, Johnson, aided by impresario Frank Yeigh, toured as “The Mohawk Princess”, orating passionate poem-recitals while decked out in a mish-mashed Native costume which presented to Late-Victorian and Edwardian-era audiences a glamorous spectacle of Indian-ness. In the July/August 2012 issue of the Canadian magazine The Walrus, Emily Landau writes: “…and although her (Johnson’s) branding played into the stereotypes, her stories broke (the audiences) down.” Poems such as “The Indian Thief” and “A Cry from an Indian Wife” (both featured here) gave Native women a voice – using Victorian melodrama to present brief morality tales where what the Native woman says is right. Landau remarks that Johnson performed with “a mix of poise and campy histrionics. In a trademark flourish, she (would) shed the buckskin during intermission, returning in a staid silk evening gown and pumps, eliciting gasps from spectators as they marveled at the transformation. The two modes of dress served as an external manifestation of Johnson’s own dual identity: her (other) name, Tekahionwake, meant “double life” in Mohawk.”

Landau continues: “In an 1892 essay entitled “A Strong Race Opinion: On the Indian Girl in Modern Fiction,” Johnson called out white writers for their generic, latently racist depictions of Native femininity. Without fail, she says, the Indian girl, always named Winona or some such, has no tribal specificity, merely serving as a self-sacrificing, mentally unhinged outlet for the white hero’s magnanimity. Johnson entreated writers to give their “Indian girl” characters the same dignity and distinction as they did their white characters. “Let the Indian girl in fiction develop from the ‘dog-like,’ ‘fawn-like,’ ‘deer-footed,’ ‘fire-eyed,’ ‘crouching,’ ‘submissive’ book heroine into something of the quiet, sweet womanly woman if she is wild, or the everyday, natural, laughing girl she is if cultivated and educated; let her be natural,” she wrote, “even if the author is not competent to give her tribal characteristics.”

In her own act, Johnson drew from the dominant white theatrical modes. Melodrama, the most popular form in the late nineteenth century, was characterized by an excess of spectacle, histrionic gestures, and amplified emotions. With her over-the-top theatrics, she was a hit with crowds hungry for sentiment. One of her most popular stories, “A Red Girl’s Reasoning,” tells of a young half-Indian woman who leaves her husband after he refuses to recognize the legitimacy of her nation’s rituals; another heroine, the half-Cree Esther of “As It Was in the Beginning,” kills her faithless white lover.”

Johnson stopped touring in 1909. She had developed breast cancer, and worsening health led to early retirement. Settling in Vancouver, she still wrote – adapting stories as told to her by her friend, Squamish Chief Joseph Capilano. Johnson died in 1913; a monument – and her ashes – are in Vancouver’s Stanley Park.

And – we quote Landau again: “…Enterprising as she was, Johnson was also an idealist. Her proud biracial identity, within which her Aboriginal and European selves peacefully coexisted, constituted an anomaly in an era when race was considered a fixed trait. The unified persona she presented onstage, nurtured in her childhood and reflected in her writings, represented more than just an amplified, campy theatrical ruse: it was a vision of what she imagined for Canada. Surveying Canada’s beaming multiculturalism today, flawed as it may be, Johnson seems like quite an oracle.”

.

We wish to thank editor Emily Landau of Toronto Life for her critical analysis of the career of Pauline Johnson.

. . . . .

“Bright Horizon” by Ahmad Shamlu احمد شاملو

Posted: March 29, 2013 Filed under: Bright Horizon by Ahmad Shamlu, English, Farsi / Persian | Tags: Easter poems Comments Off on “Bright Horizon” by Ahmad Shamlu احمد شاملواحمد شاملو

Ahmad Shamlu (1925-2000, Tehran, Iran)

Ahmad Shamlu (1925-2000, Tehran, Iran)

“Bright Horizon”

.

Bright horizon

Some day we will find our doves

Kindness will take Beauty by the hand

.

That day – the least song will be a kiss

and every human being be brother to

every other human being

.

That day – house doors will not be shut

Locks will be but legends

And the Heart be enough for Living

.

The day – that the meaning of all speech is loving

so one won’t have to search for meaning down to the last word

The day – that the melody of every word be Life

and I won’t be suffering to find the right rhythm for every last poem

.

That day – when every lip is a song

and the least song will be a kiss

That day – when you come – when you’ll come forever –

and Kindness be equal to Beauty

.

The day – that we toss seeds to the doves…

and I await that day

even if upon that day I myself no longer be.

. . . . .

We are grateful to Hassan H. Faramarz for the Persian-to-English translation of “Bright Horizon”.

Poemas para El Día Internacional de la Mujer: una poetisa anishinaabe que deseamos honrar: Joanna Shawana / Poems for International Women’s Day: an Anishinaabe poet we wish to honour: Joanna Shawana

Posted: March 8, 2013 Filed under: English, Joanna Shawana, Joanna Shawana: poetisa anishinaabe/Anishinaabe poet, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: Poemas para El Día Internacional de la Mujer, Poems for International Women's Day Comments Off on Poemas para El Día Internacional de la Mujer: una poetisa anishinaabe que deseamos honrar: Joanna Shawana / Poems for International Women’s Day: an Anishinaabe poet we wish to honour: Joanna Shawana

ZP_Manitoulin Island artist Daphne Odjig_Echoes of the Past_Daphne Odjig_Pintora indígena de la Isla de Manitoulin_Ecos del Pasado

Joanna Shawana / Niimkiigiihikgad-Kwe

(Anishinaabe poet from Wikwemikong, of the Ojibwe-Odawa First Nations Peoples, Mnidoo Mnis/Manitoulin Island, Ontario)

“Grandmother Moon”

.

During this cold dark night

Grandmother Moon sits high

Above the sky

.

Our Grandmother

Surrounded with stars

Emphasizing the life of the universe

.

As the night comes to end

Our Grandmother Moon slowly fades

Over the horizon

.

To greet Grandfather Sun

To greet him

As the new day begins

.

Grandmother Moon will rise again

She will shine and guide me on my path

As I walk on this journey.

. . .

Joanna Shawana / Niimkiigiihikgad-Kwe

(Poetisa anishinaabe de Wikwemikong, Mnidoo Mnis/Isla de Manitoulin, Ontario, Canadá)

“La Luna – Mi Abuela”

.

Durante esta noche fría y oscura

La Luna Mi Abuela se sienta

Alta en el cielo

.

Nuestra Abuela

Está rodeada de estrellas

Que hacen hincapié en la vida del universo

.

Como cierra la noche

Lentamente Nuestra Abuela La Luna destiñe

Encima del horizonte

.

Para dar la bienvenida al Abuelo El Sol

Para saludarle

Como comienza el nuevo día

.

Ella saldrá de nuevo, La Luna-Abuela,

Brillará y me guiará en mi camino

Como ando en este paso.

. . .

“All I Ask”

.

My fellow woman

My sisters

I am weak

I am hurt

All I ask of you is

Please

Hear what I have to say

Hear what I have to share

I am not here

To be looked down

I am not here

To be judged

For what had happened to me

All I ask of you is

Please

Hear what I have to share

My fellow women

My sisters

Listen to my words

See the pain in my eyes

All I ask of you is

Please

Hear what I have to say

Hear what I have to share

Help me

To get through my pain

Help me

To understand what is happening

Help me

To be a better person

So please

Hear what I have to say

Hear what I have to share.

. . .

“Todo lo que te pido…”

.

Mi compañera

Mis hermanas

Soy débil

Estoy dolida

Todo lo que te pido es

Por favor, escucha lo que tengo que decir

Escucha lo que tengo que compartirte

No estoy aquí

Para ser mirada por ustedes por encima del hombro

No estoy aquí

Para ser juzgada de

Lo que me había pasado

Todo lo que les pido es

Por favor, escuchen lo que tengo que compartirles,

Mis compañeras, mis hermanas,

Escuchen mis palabras

Vean el dolor en mis ojos

Todo lo que les pido es

Por favor,

Escuchen lo que tengo que decir

Escuchen lo que tengo que compartirles

Ayúdame a

Superar mi sufrimiento

Ayúdenme a

Comprender lo que pasa

Ayúdenme a

Ser una mejor persona

– Entonces,

Por favor,

Escucha lo que tengo que decirte,

Escuchen lo que tengo que compartir con ustedes…

. . .

“Hidden”

.

Hidden secrets

Hidden feelings

Hidden thoughts

.

Why do people need to hide

Their secrets

Their feelings and thoughts?

.

What are people afraid of?

Afraid of their own secrets

Afraid of their own feelings and thoughts

.

How can one person reveal?

To reveal their secrets

To reveal their feelings and thoughts

.

There is no reason to hide their secrets

There is no reason to hide their feelings

There is no reason to hide their thoughts.

. . .

“Escondido”

.

Secretos escondidos

Sentimientos escondidos

Pensamientos escondidos

.

¿Por qué la gente necesita ocultar algo?

Ocultar sus secretos, sus sentimientos y sus pensamientos

.

¿De qué tiene miedo la gente?

Tiene miedo de sus propios secretos,

Tiene miedo de sus corazonadas y sus ideas

.

¿Cómo revele una persona?

A revelar sus secretos

A revelar sus pensamientos

.

No hay razón para ser una tumba

No hay razón para engañarse a sí mismo sus sentimientos

No hay razón para esconder sus pensamientos.

. . .

“Wandering Spirit”

.

This wandering spirit of mine

Wanders off to the world of the unknown

The unknown of today and tomorrow

.

This wandering spirit of mine

Waits to hear your voice

Waits to listen for what will be said

.

This wandering spirit of mine

– Help me to discover the unknown

– Help me to understand

What the unknown needs to offer

.

Help this wandering spirit

That wanders off to the world of the unknown

That wonders what the future holds

.

This wandering spirit of mine

– Help me find peace and harmony

– Help me find tranquillity in life.

. . .

“Espíritu vagabundo”

.

Mi espíritu vagabundo

Se aleja al mundo de lo desconocido

Lo desconocido de hoy, de mañana

.

Este espíritu mío errante

Está aguardando tu voz

Está aguardando por lo que diremos

.

Espíritu mío, espíritu vagabundo

– Ayúdame a descubrir lo desconocido

– Ayúdame a entender

Lo que lo desconocido necesita ofrecerme

.

Ayúda a este espíritu errante

Que se aleja al mundo de lo desconocido

Y que se pregunta lo que va a contener el futuro

.

Este espíritu mío, mi espíritu andante

– Ayúdame a encontrar la paz y la armonía

– Ayúdame a encontrar la tranquilidad en la vida.

“Walk with Me”

.

Come and walk with me

On this path

Which I am walking on

.

We might slip and fall

To the cycle

That we once lived in

.

Let us

Help each other to understand

What we have been through

.

Let us walk together

Come and hold my hand

Hold it tight and never let go

.

Come and walk with me

Let us find what our future holds for us

Let us walk together on this path.

. . .

“Camina conmigo”

.

Ven – camina conmigo

A lo largo de este camino

Donde estoy caminando

.

Resbalemos y caigamos

Al ciclo

Que estaba nuestra vida

.

Ayudémonos a comprender,

La una a la otra,

Lo que salimos adelante, lo que sobrevivimos

.

Caminemos juntos,

Ven – toma mi mano –

Agárrate bien – nunca suéltame la mano

.

Ven – camina conmigo

Busquemos lo que habrá para nosotros en el futuro

Caminemos juntos en este camino.

. . .

Joanna Shawana moved down to Toronto in 1988. She began writing in 1994. A single parent, and now a grandmother, she has worked for an agency providing services to Native people in the city – Anishnawbe Health Toronto. Her bio. from her book of poems Voice of an Eagle states: A Catholic upbringing clashed with Native heritage teachings, which confused her path. However, through the years she gained more knowledge from her Native elders and began to clearly understand what it meant to be Nishnawbe Kwe (Native Woman). Thus, her journey in stabilizing her identity began… Joanna writes: ” When I look back and see what I have left behind, inside I cry for the little girl who witnessed that life, the teenager who was abused, and the woman who almost gave in, but I know now that my inner strength will never allow me to leave my path. Healing is a continuous part of life and it will be so until the day comes that the Creators call me. So as you travel along your path, remember – do not give in or give up! ”

.

Joanna Shawana fue víctima de mucho maltrato durante su juventud, también como una mujer joven. Desde 1988 ha vivido en la ciudad de Toronto donde trabaja con la agencia indígena Fortaleza de Anishnawbe Toronto. Dice: ” La curación es una parte continua de la vida y ésa será hasta que el día que me llamarán los Creadores. Entonces, mientras viajas en tu camino, recuerda – ¡no te des por vencido y no dejes de intentar! ”

.

Translations into Spanish / Traducciones en español: Alexander Best

. . . . .

Ngày Quốc tế Phụ nữ : Thơ Việt Nam / Poems for International Women’s Day : Vietnamese Voices : “I have crushed my dreams and turned them into a life…”

Posted: March 8, 2013 Filed under: English, Ngày Quốc tế Phụ nữ : Thơ Việt Nam / Poems for International Women's Day : Vietnamese Voices, Vietnamese | Tags: Poems for International Women's Day Comments Off on Ngày Quốc tế Phụ nữ : Thơ Việt Nam / Poems for International Women’s Day : Vietnamese Voices : “I have crushed my dreams and turned them into a life…”Dieu Nhan (Buddhist nun, 1041-1113)

“Birth, Old Age, Sickness, Death”

.

Birth, old age, sickness, death

Are commonplace and natural.

Should we seek relief from one,

Another will surely consume us.

Blind are those praying to Buddha,

Duped are those praying in Zen.

Pray not in Zen or to Buddha,

Speak not. Linger with silence.

.

(translation: Huu Ngoc, Lady Borton)

Dam Phuong (1881-1947)

“Flood Relief” (around 1928)

.

Harsh winds and the relentless rains drown

Districts that were once Thanh Hoa towns,

Swirling them down river, the water brown.

Warn the world: Silence is a stand,

.

Silence without opening your heart and hand.

Labourers reach out in crises of need,

Women with their gentleness take a lead,

Only then do the palace chiefs heed.

.

From this time on, we understand “kindness”,

Everyone joining in to ease public distress,

Those from humble trades with help appear,

Women draw on friends far and near.

.

(translation: Lady Borton)

Mong Tuyet (1914-2007)

“The price of rice in Tràng An” (1945)

(for Van Muoi, clerk at a flower shop in Tri Duc Garden)

.

I hear the price of rice in Trang An is high.

Starving for food, thirsting for life-saving rain,

Our friends and family in the centre and the north

Are desperately hoping rice will be sent from Dong Nai.

.

Grief dazes our nation’s artists.

You encouraged me to study poetry,

You want to release the ink of my poetic spirit.

Lost in a literary forest, I was building a road out.

.

I carried your books back home.

The people awaiting rice are in agony.

Sister, with my poor skills, how can I help?

You’d answer:

“I’ll sell literature, you sell flowers.”

.

(translation: Xuan Oanh, Lady Borton)

Tràng An is an old name for the city of HaNoi.

An important railway route and main road lay destroyed at the end of WWII,

hence rice did not reach enough people.

In Viet Nam, two million people had died of starvation by the end of the war.

.

Tran Thi My Hanh (born 1945)

“The road repair team at Jade Beauty Mountain” (1968)

.

Jade Beauty Mountain at Van River

Deserted at mid-day, buzzes with heat.

The mountain looks like a beautiful girl

Reclining, her eyes searching the azure sky.

.

Clouds like friends surround the Beauty.

Below are women workers from a road team,

Their youth and strength breaking a new trail,

Their hands skilled with hoes and quick with guns.

.

Pity the road circling the mountain,

Bomb craters slashing into bomb craters,

Olive trees, oak trees blackened with resin,

The birds scattered, ripped from their flocks,

Every rock on Beauty Mountain cringing in pain,

The earth tumbling down into the lowland paddies,

Night after night as the Beauty Mountain lies awake.

The women repairing the road are uneasy;

With torches, they search their way forward.

For them, a bite of dried bread is a delicious treat.

.

The green jackets that arrived yesterday

Were completely mended today (it was nothing).

Despite beating sun, pouring rain and bitter smoke,

The chop chop of hoes lifts skyward until after midnight.

.

The battlefield is here – The Front is here,

We fight the enemy for every inch of this road,

We shovel, shovel rock that smells of the mountain,

Our blood and sweat blending with the mountain’s basalt.

.

I hear the startling horns of passing trucks,

Feel my blood and the road’s blood pulse as one.

We, women with hearts as pure and dazzling as jade,

Stretch in a silhouette along the ridge of Beauty Mountain.

.

(translation: Lady Borton)

Jade Beauty Mountain is in northern Viet Nam’s Red River Delta. Route 1 is nearby,

and this major north-south road served as supply route during the U.S.–VietNam War.

Route 1 was bombed often by American planes.

Ha Phuong (born 1950)

“A meal by a stream” (1971)

.

A platoon of twelve

Four mess kits of cold rice

A packet of jerky

Wild vegetables from the forest

A minute to rest by a stream.

The fire hisses, as if urging the soup to boil –

.

With no dining table,

Some stand, some sit.

The steep mountain pass has quickened our hunger,

We hastily spread a leaf to make a small tray;

A mouthful of dry rice

When you’re hungry is delectable.

.

Jokes, teasing, the crisp sound of laughter,

A mess kit of cold rice, a few minutes’ pause.

“There’s still salt. The rice is tasty…”

The sound of laughter

The sound of laughter spreads.

.

Our unit’s meal is strangely joyful:

We’re far from our parents

But share the love of comrades.

On the Trail these days as we fight the Americans,

Our forest meals are delicious feasts.

.

(translation: Lady Borton)

Thuy Bac (1937-1996)

“Thread of Longing, Thread of Love” (1977)

.

Truong Son East

Truong Son West

.

On one side, sun burns

On the other, rain circles

.

I extend my hand

I open my hand

.

Impossible

To cover you

.

Pull this thread of love

To splice a roof

.

Pull this thread of longing

To weave a blue dome

.

Bend the Eastern Range

To cover you from the rain

.

Bend the Western Range

To spread a cool shadow

.

Canopy the sky with love

Of purest blue

.

I bend everything

Toward you.

.

(translation: Le Phuong, Wendy Erd)

The Ho Chi Minh Trail – a series of old mountain paths used for supply routes

by the North VietNamese during the U.S.–VietNam War –

passed through Truong Son (the Long Mountains).

.

Doan Ngoc Thu (born 1967)

“The city in the afternoon rain” (1992)

The city in the afternoon rain:

A beggar sits singing

A song from the war.

.

The city in the afternoon rain:

Roaming children

Vie for the bubbles they blow

And for fallen almonds.

.

The city in the afternoon rain:

Near a small roadside inn,

Cigarette ashes eddy with a burnt match

And a return ticket filled with nostalgia.

.

The city in the afternoon rain:

Suddenly I run into you,

You’re just as before – proud and harsh.

You step silently through the rain

To the beggar’s side

And weep –

At the song echoing the time of war.

.

(translation: Xuan Oanh, Lady Borton)

The war referred to is the U.S.–VietNam War.

. . .

. . .

Tran Mong Tu (born 1943)

“Lonely Cat” (1980)

.

The cat sprawls in the yard

Lonely, playing with sunlight.

Inside the window

Lonely, I’m watching him.

.

On grass green as jade,

Alone, his white back spins.

Sun shimmers down, drop by drop

The cat turns round my sadness.

.

I see myself in the glass,

A dim shadow, its outline vague:

The gate to marriage shut tight,

Imprisoning me so gently.

.

The cat has his corner of grass,

I, my dim pane.

We two, so small.

Our loneliness uncontained.

.

Dear cat in the sun,

Assuage my sadness.

My ancient homeland, my former lover,

Still soak my soul.

.

(translation: Le Phuong, Wendy Erd)

Tran Thi Khanh Hoi (born 1957)

“The Pregnant Woman” (1990)

She came to me,

Her eyes like the waves of a river in flood,

Her voice choking

At its source, then gushing like a waterfall,

Her breasts throbbing with milk about to flow,

Her unborn child kicking at my side.

In a few days, birth will release

The child’s hands and feet, its wails and cries,

But right now the mother sits waiting in weariness,

Like an arid field as the rising flood approaches its limit.

.

Angry at her husband, who won’t stop drinking,

She’s been pregnant throughout a season of hard labour.

Fears about her ill-treated baby

Have aged her,

Have left her fearful

Of the wealthy screaming for the money owed them,

Unmoved by the pain of a worried

Woman who is pregnant.

.

She came to me,

Seeking consolation, protection, sympathy.

What could I say when we can’t stop the inevitable?

The time is soon for this pregnant woman.

I swim through waves of silt from the flood,

Tonight –

.

(translation: Xuan Oanh, Lady Borton)

. . .

. . .

Huong Nghiem (born 1945)

“I don’t know” (1991)

.

Thinking of

The endless Universe,

I am suddenly aware:

The sun is very small.

Thinking of

Endless love,

I realize:

I am limited by you.

Instead of letting my own ego expand,

I am absorbed

In scrubbing

Your shirt collar clean.

But to what end

I don’t know.

.

(translation: Nguyen Quang Thieu, Lady Borton)

Le Thu (born 1940)

“My Poem” (1990)

.

I want you to be the ocean

Never ending, forever strange.

But I fear your heart may run too deep

For me to reach its limits.

.

I want you to be a river

Depositing rich soil on its banks.

But I fear the river’s length;

When does flowing water return?

.

I want to hear your words in a vow

To be sure you are mine forever.

But I fear flying high unfettered;

Yet how can I bind your wings?

.

I want you to be the moon,

Full on the fifteenth of the lunar month,

But I fear the next days’ waning;

Would our love also fade with the season?

.

So! You should be a poem

Gently entering my heart.

Then, our love forever young

Can be compassionate and complete!

.

(translation: Xuan Oanh, Lady Borton)

Nguyen Bao Chan (born 1969)

“For my father” (1995)

.

Looking at your hands

I see the lines

Splitting into the future and an exhausting past

I see also the sky of my youth,

How I drifted in dreams, following the moon and stars.

Father,

Time has rushed on

I have crushed my dreams and turned them into a life

I have held the broken pieces of your life in these frail hands

I have ground the shards to bluntness, ground them some more,

In order to live, love, and protect myself.

If ever I’m inattentive to you, broken

And reduced to pieces,

I know you will pick up the shards

Even though they cut your hands and give you pain.

.

(translation: Lady Borton)

Y Nhi (born 1944)

“Longing” (1998)

To leave

like a boat pulling away from a dock at dawn

while waves touch the sandbar, saying goodbye

.

Like a still-green leaf torn from a branch

leaving only a slight break in the wood

.

Like a deep purple orchid

gradually fading and

then one day closing off like an old cocoon

.

To leave

like a radiant china vase displayed on a brightly lit shelf,

as the vase starts to crack

.

Like a lovely poem ripped from a newspaper

first sad

then elated

as it flies off like a butterfly in late summer

.

Like an engagement ring

slipping off a finger

and hiding itself among pebbles

.

To leave

like a woman walking away from her love.

.