José Guadalupe Posada: the ‘calaveras’ of a Mexican master of social reportage and satire

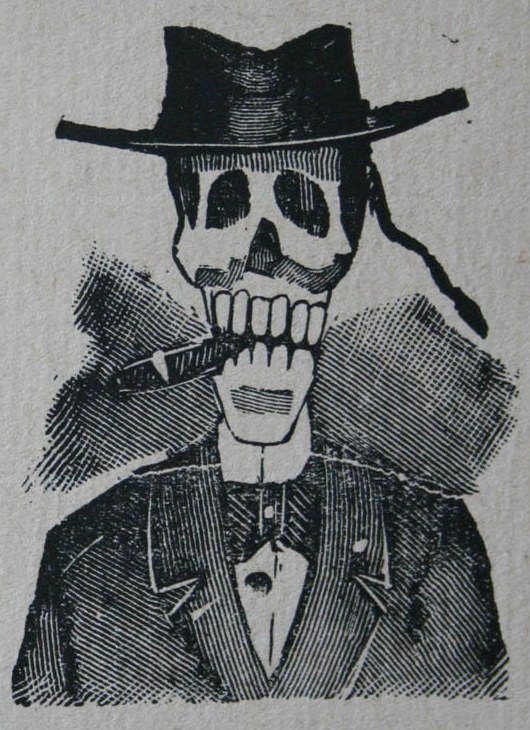

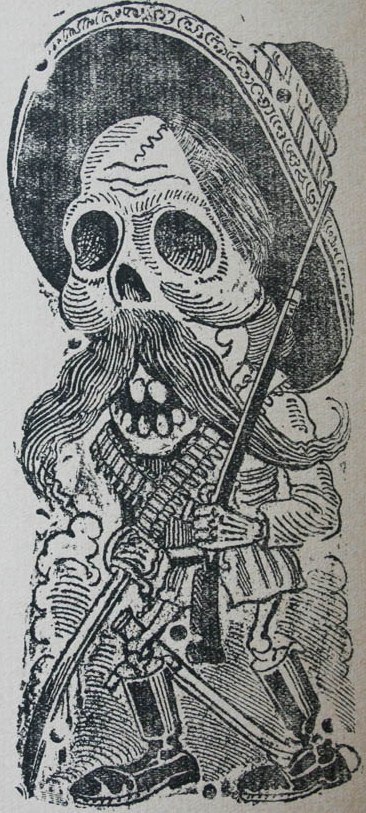

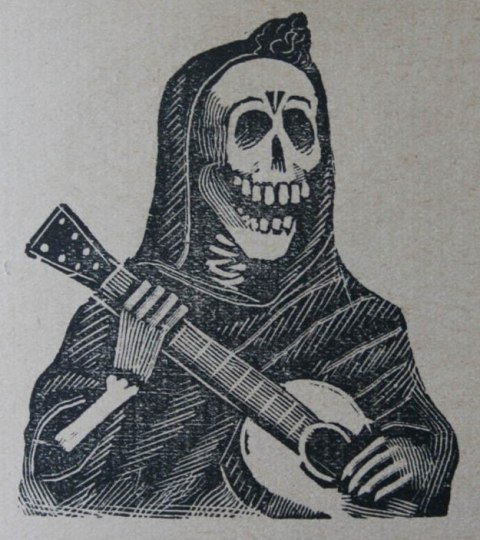

Posted: November 2, 2014 Filed under: Alexander Best, IMAGES, Retratos por José Guadalupe Posada | Tags: Day of the Dead (Mexico) Comments Off on José Guadalupe Posada: the ‘calaveras’ of a Mexican master of social reportage and satireThe etchings of José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913) demonstrated a worldview that was, and often still is, profoundly Mexican. A commercial illustrator who also printed political broadsides, Posada invented the ‘calavera’ portrait. Calavera means skull, and by extension, skeleton. Aspects of the nation’s Indigenous heritage (skulls and death-goddesses were central to Aztec and Maya cultures) plus its Spanish cultural inheritance (death-oriented monastic orders, the ‘dance of death’ and ‘memento mori’ traditions) combine in Posada’s rustic yet sophisticated prints to give us the flavour of the average Mexican’s stoical yet humorous appreciation of Death.

……….

A Sincere Tale for The Day of The Dead :

“ Lady Catrina goes for a stroll / Doña Catrina da un paseo ”

*

“¡ Santa Mictecacihuatl !

These Mandible Bone-nix (Manolo Blahniks) weren’t meant for

The Long Haul – certainly not worth the silver I shelled out for ’em ! ”

Thus spoke that elegant skeleton known as La Catrina.

And she clunked herself down at the stone curb, kicking off the

jade-encrusted, ocelot-fur-trimmed high-heel shoes.

“ Well, I haven’t been ‘bone-foot’ like this since I was an escuincle. ”

She chuckled to herself as she began rummaging through her Juicy handbag.

Extracting a shard of mirror, she held it up to her face – a calavera

with teardrop earrings grinned back at her. ¡Hola, Preciosa!

she said to herself with quiet pride. She adjusted her necklace of

cempasúchil blossoms and smoothed her yellow-white-red-and-black

designer-huipil.

*

Just then a lad and lassie crossed her path…

“ Yoo-hoo, Young Man, Young Woman !

Be dears, would you both, and escort an old dame

across La Plaza de la Existencia ! My feet are simply

worn down to the bone ! ”

*

“ Certainly, madam – but we’re new here…

Where is La Plaza de la Existencia ? ”

*

“ We’re just at the edge of it – El Zócalo ! ”

And La Catrina gestured beyond them where an

immense public square stretched far and wide.

She clasped their hands – the Young Man on her left,

the Young Woman on her right – and the trio set out

across a sea of cobbles…

*

By the time they reached the distant side of the Plaza the

Young Man and Young Woman had shared much with the

calaca vivaz – their hopes, fears, sadness and joy – their Lives.

*

The Woman by now had grown a long, luxurious

silver braid and The Man a thick, salt-and-pepper

beard. Both knew they’d lived fully – and were satisfied.

But my… – they were tired !

*

In the company of the strange and gregarious Catrina 5 minutes

to cross The Zócalo had taken 50 years…

*

“ Doña Catrina, here we are at your destination – will you be

alright now ? ”

*

“ Never felt better, Kids ! I always enjoy charming company

on a journey ! ” And she winked at them, even though she had

no eyeballs – just sockets. “ Join me for a caffè-latte? Or a café-pulque,

if you’re lactose-intolerant ! ”

*

“Thank you, no,” said the Man and Woman, in unison.

And both laughed heartily, breathed deeply, and sat down

at the curb.

*

When they looked up, Doña Catrina had clattered gaily out of sight.

And before their eyes the vast Zócalo became peopled with

scenes from their Lives.

The Man and Woman smiled, then sighed contentedly. And, side by side, they leaned closer together – and died.

* finis *

Alexander Best – November 2nd, 2011

……….

Glossary:

Mictecacihuatl – Aztec goddess of the AfterLife, and Keeper of The Bones

La Catrina – from La Calavera Catrina (The Elegant Lady-Skull),

a famous zinc etching by Mexican political cartoonist and print-maker

Jose Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913). Posada’s “calavera” prints depict

society from top to bottom – even the upper-class woman of wealth –

La Catrina – must embrace Death, just like everyone else…

She has since become a “character”,

invented and re-invented, for The Day of The Dead (Nov.2nd).

escuincle – little kid or street urchin

calavera – skull

¡Hola, Preciosa! – Hello, Gorgeous!

cempasúchil – marigold (the Day of The Dead flower)

huipil – blouse or dress, Mayan-style

El Zócalo – the main public square (plaza mayor) in Mexico City,

largest in The Americas

calaca vivaz – lively skeleton

pulque – a Mexican drink make from fermented

agave or maguey – looks somewhat like milk

……….

Claribel Alegría: And I dreamt that I was a tree / I love to handle leaves / A Letter to “Time” / Autumn

Posted: October 28, 2014 Filed under: Claribel Alegría, Claribel Alegría: And I dreamt that I was a tree, English, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Claribel Alegría: And I dreamt that I was a tree / I love to handle leaves / A Letter to “Time” / AutumnClaribel Alegría (Nicaragua / El Salvador, nacido 1924)

Y soñe que era un árbol – a Carole

(1981)

.

Y soñe que era un árbol

y que todas mis ramas

se cubrían de hojas

y me amaban los pájaros

y me amaban también

los forasteros

que buscaban mi sombra

y yo también amaba

mi follaje

y el viento me amaba

y los milanos

pero un día

empezaron las hojas

a pesarme

a cubrirme las tardes

a opacarme la luz

de las estrellas.

Toda mi savia

se diluía

en el bello ropaje

verdinegro

y oía quejarse a mi raíz

y padecía el tronco

y empecé a despojarme

a sacudirme

era preciso despojarse

de todo ese derroche

de hojas verdes.

Empecé a sacudirme

y las hojas caían.

Otra vez con más fuerza

y junto con las hojas que importaban apenas

caía una que yo amaba:

un hermano

un amigo

y cayeron también

sobre la tierra

todas mis ilusiones

más queridas

y cayeron mis dioses

y cayeron mis duendes

se iban encogiendo

se arrugaban

se volvían de pronto

amarillentos.

Apenas unas hojas

me quedaron:

cuatro o cinco

a lo sumo

quizá menos

y volví a sacudirme

con más saña

y esas no cayeron

como hélices de acero

resistían.

. . .

Claribel Alegría (Nicaragua / El Salvador, born 1924)

And I dreamt that I was a tree – To Carole

(1981)

.

And I dreamt that I was a tree

and all my branches – leafy –

were belovéd of the birds

– and of strangers seeking my shade.

And I too loved my canopy,

as did the wind – and the hawks.

But there came the day when

my leaves weighed heavily upon me,

they blocked out my afternoons

and the light of the stars.

My sap became diluted by

my gorgeous dark-green robe;

my roots were heard groaning

and the trunk of me, how it suffered;

and I began to dis-robe myself,

to shake loose;

I needed to be free of

that profusion of green leaves.

I really shook; and the leaves fell.

Again, more fiercely,

and more leaves fell – along with a certain one I loved:

a brother? friend?

And then there fell right to the ground all the illusions

most dear to me.

My gods fell, my charms, my animating spirits.

Dried up, wrinkled, completely yellowed.

I had hardly any leaves left, four or five at the very most;

and I shook again, in total fury.

The last of these leaves, no, they wouldn’t fall;

like steel helixes they clung to me.

. . .

Carta al Tiempo (1982)

.

Estimado señor:

Esta carta la escribo en mi cumpleaños.

Recibí su regalo. No me gusta.

Siempre y siempre lo mismo.

Cuando niña, impaciente lo esperaba;

me vestía de fiesta

y salía a la calle a pregonarlo.

No sea usted tenaz.

Todavía lo veo

jugando al ajedrez con el abuelo.

Fue perdiendo su brillo.

Y usted insistía

y no respetaba la humildad

de su carácter dulce,

y sus zapatos.

Después me cortejaba.

Era yo adolescente

y usted con ese rostro que no cambia.

Amigo de mi padre

para ganarme a mí.

Pobrecito del abuelo.

En su lecho de muerte

estaba usted presente,

esperando el final.

Un aire insospechado

flotaba entre los muebles.

Parecían mas blancas las paredes.

Y había alguién más,

usted le hacía señas.

Él le cerró los ojos al abuelo

y se detuvo un rato a contemplarme.

Le prohibo que vuelva.

Cada vez que lo veo

me recorre las vértebras el frío.

No me persiga más,

se lo suplico.

Hace años que amo a otro

y ya no me interesan sus ofrendas.

¿Por qué me espera siempre en las vitrinas,

en la boca del sueño,

bajo el cielo indeciso del domingo?

Sabe a cuarto cerrado su saludo.

Lo he visto el otro día con los niños.

Reconocí su traje:

el mismo tweed de entonces

cuando era yo estudiante

y usted amigo de mi padre.

Su ridículo traje de entretiempo.

No vuelva,

le repito.

No se detenga más en mi jardín.

Se asustarán los niños

y las hojas se caen:

las he visto.

¿De qué sirve todo esto?

Se va a reír un rato

con esa risa eterna

y seguirá sabiéndome al encuentro.

Los niños,

mi rostro,

las hojas,

todo extraviado en sus pupilas.

Ganará sin remedio.

Al comenzar mi carta lo sabía.

A Letter to “Time” (1982)

.

Dear Sir:

I am writing this letter to you on my birthday.

I received your gift – and I don’t like it.

Always, always it’s the same thing.

When I was a girl, impatiently I waited;

got all dressed up, and went out into the street

to proclaim it.

Don’t be stubborn.

I can still picture you playing chess with my grandfather,

and at first your appearances were few and far between,

but soon they were daily and

grandfather’s voice lost its sparkle.

And you insisted on such visits, without any respect for

the humbleness of his gentle soul – or his shoes.

Later on, you attempted to court me.

Of course I was still young – and you with your unchanging face:

a friend of my dad’s with an eye trained on me.

Oh, poor Grand-dad…And didn’t you hang around his deathbed

till the end came!

The very walls seemed to fade out, and there was a kind of

unpinpointable something or other floating among the rooms.

You were that someone who was making signs and wonders,

and Dad closed Grand-dad’s eyes – then paused to contemplate me.

I forbid you to return…

Every time I see you my spine goes stiff – stop pursuing me, I beg you.

It’s been years since I loved anyone else

but your gifts no longer interest me.

Why are you waiting for me, in shop windows,

in the mouth of my dreams,

beneath a vague Sunday sky?

Your greeting reminds me of the air in shut-up rooms.

The other day I saw you with some kids;

I recognized that tweed suit, from when I was a student and

you were my father’s friend – that ridiculous Autumn tweed suit!

I repeat: Don’t come back, don’t hang around my garden;

you’ll scare the children and the leaves will all drop (I’ve seen it happen.)

What’s the use in all of this?

You’ll laugh a little, with that forever-laugh of yours,

and you’ll keep popping up.

The kids, my face, the falling leaves…

we all go lost or missing – in your eyes.

There’s no remedy for any of this: you’ll win.

I knew that from the moment I put pencil to paper.

. . .

Otoño (1981)

.

Has entrado al otoño

me dijiste

y me sentí temblar

hoja encendida

que se aferra a su tallo

que se obstina

que es párpado amarillo

y luz de vela

danza de vida

y muerte

claridad suspendida

en el eterno instante

del presente.

. . .

Autumn (1981)

.

You told me:

You’ve entered your Autumn.

And I shudder,

a leaf aflame that clings to its stem,

obstinate,

a yellow eyelid,

the light of a candle,

a dance of both life and death,

Open-ness hanging

in that eternal instant of the present.

. . .

Me gusta palpar hojas (1997)

.

Más que libros

revistas

y periódicos

más que móviles labios

que repiten los libros,

las revistas,

los desastres,

me gusta palpar hojas

y sentir su frescura,

ver el mundo

a través de su luz tamizada

a través de sus verdes

y escuchar mi silencio

que madura

y titila en mis labios

y se rompe en mi lengua

y escuchar a la tierra

que respira

y la tierra es mi cuerpo

y yo soy el cuerpo

de la tierra

Claribel.

. . .

I love to handle leaves (1997)

.

More than books,

more than magazines or newspapers,

more even than moving lips that recite from books, magazines, disasters…

how I love to handle leaves

– to feel their freshness,

to see the world through their filtered light,

through their green-ness;

and to hear my own silence

maturing – a-twinkling – upon my lips,

breaking against my tongue;

and to listen to the earth breathing.

And the earth is my body,

and I am the body of a land called

Claribel.

. . .

Translations from Spanish to English: Alexander Best

. . . . .

नया साल मुबारक हो Poema para Diwali

Posted: October 23, 2014 Filed under: Alexander Best, Spanish Comments Off on नया साल मुबारक हो Poema para DiwaliPoema para Diwali

.

Abran las ventanas, abran las puertas

– ¡llega Diwali est’anochecer!

Ignorancia –¡esfúmate! – ¡Comprensión nacerá!

Ofrezcan gran Luz con lámparas de aceite,

y entonen el mantra que Laksmí entre.

Ganesha, también, veneramos este día,

y la exaltada Kali con su intensa manera.

Se desmaterializa Desesperanza y Esperanza se consolida;

y triunfa Bondad, no Mal.

Niños lanzan sus barcos-papel y flotan llamas en arroyos y charcos,

pues explotan petardos – un gozo ‘chamaco’ –

y todo que pasa celebra La Luz

esta noche de luna nueva.

Mis compañeras se apuntan Diwali

– aquí en Toronto, Canadá.

Merle y Kasturie; Suba, Nanthini

– de Trinidad y de Sri Lanka.

Mezclando comida, familia, amigos y diversión,

El Diwali – como Cinco de Mayo – es la fecha de reunión.

. . . . .

https://zocalopoets.com/category/poems/hindi/

Jorge Luis Borges: “Eternity” / “Eternidad” / “Ewigkeit”

Posted: October 15, 2014 Filed under: English, Jorge Luis Borges, Spanish Comments Off on Jorge Luis Borges: “Eternity” / “Eternidad” / “Ewigkeit”Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986, Argentina)

Ewigkeit (“Eternity”)

.

Let Spanish verse turn on my tongue, affirm

Once more in me what it has always said

Since Seneca in Latin: that true dread

Sentence that all is fodder for the worm.

Let it turn back with song to hail pale ash,

The calends of death, and the victory

Of that word-ruler queen whose footfalls smash

The banners of our empty vanity.

Not that. I’ll cravenly deny not one

Thing that has blessed my clay. I know of all

Things, one does not exist: oblivion.

That in eternity beyond recall

The precious things I’ve lost stay burning on:

That forge, that risen moon, that evening-fall.

. . .

Jorge Luis Borges

Ewigkeit (“Eternidad”)

.

Torne en mi boca el verso castellano

a decir lo que siempre está diciendo

desde el latín de Séneca: el horrendo

dictamen de que todo es del gusano.

Torne a cantar la pálida ceniza,

los fastos de la muerte y la victoria

de esa reina retórica que pisa

los estandartes de la vanagloria.

No así. Lo que mi barro ha bendecido

no lo voy a negar como un cobarde.

Sé que una cosa no hay. Es el olvido;

sé que en la eternidad perdura y arde

lo mucho y lo precioso que he perdido:

esa fragua, esa luna y esa tarde.

. . .

Ewigkeit es Eternidad en alemán.

Ewigkeit means Eternity in German.

. . .

Visit translator A.Z. Foreman’s Poems Found In Translation site:

http://poemsintranslation.blogspot.ca/

. . . . .

Two “Autumn” Poems: translations by A.Z. Foreman

Posted: October 15, 2014 Filed under: Dino Campana, English, German, Italian, Rainer Maria Rilke Comments Off on Two “Autumn” Poems: translations by A.Z. ForemanDino Campana (1885-1932, Italy)

Autumn Garden

.

Unto the ghostly garden, unto the laurels mute

Of the green garlands,

Unto the autumn land

– one last salute!

Out to the dried hillsides

Reddened hard in the terminal sun,

Confounded into grumbles,

Gruff life afar is crying:

Crying to the dying sun that sheds

A blood that dyes the flowerbeds.

A brass band plays

Ear-piercingly away; the river fades

Out amidst the gilded sands. In the quiet

The great white statues stand at the bridgehead

Turned; and what was once is now no more.

And from the depths of quiet, as if it were a chorus

Soft and splendorous

Yearns its way to the heights of my terrace.

And in an air of laurel,

In an air of laurel, languorous and blade-bare,

Among the statues immortal under sundown,

She appears to me – is there.

. . .

Dino Campana

Giardino Autunnale

.

Al giardino spettrale al lauro muto

De le verdi ghirlande

A la terra autunnale

Un ultimo saluto!

A l’aride pendici

Aspre arrossate nell’estremo sole

Confusa di rumori

Rauchi grida la lontana vita:

Grida al morente sole

Che insanguina le aiole.

S’intende una fanfara

Che straziante sale: il fiume spare

Ne le arene dorate: nel silenzio

Stanno le bianche statue a capo i ponti

Volte: e le cose già non sono più.

E dal fondo silenzio come un coro

Tenero e grandioso

Sorge ed anela in alto al mio balcone:

E in aroma d’alloro,

In aroma d’alloro acre languente,

Tra le statue immortali nel tramonto

Ella m’appar, presente.

. . .

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926, Bohemia-Austria-Germany)

Autumn Day

.

Lord: it is time. The summer days were grand.

Now set Thy shadows out across the sun-dials

And set the winds loose on the meadowland.

Bid the last fruits grow full upon the vine,

do them the good of two more southern days

then thrust them on to their fulfillment, chase

the final sweetness into bodied wine.

Whoever has no house yet will build none,

Whoever is alone will stay alone

And stay up, write long letters out, and go

Through avenues to wander on his own

Uneasily when leaves begin to blow.

. . .

Rainer Maria Rilke

Herbsttag

.

Herr: Es ist Zeit. Der Sommer war sehr groß.

Leg deinen Schatten auf die Sonnenuhren,

und auf den Fluren laß die Winde los.

Befiehl den letzten Früchten voll zu sein;

gieb ihnen noch zwei südlichere Tage,

dränge sie zur Vollendung hin und jage

die letzte Süße in den schweren Wein.

Wer jetzt kein Haus hat, baut sich keines mehr.

Wer jetzt allein ist, wird es lange bleiben,

wird wachen, lesen, lange Briefe schreiben

und wird in den Aleen hin und her

unruhig wandern, wenn die Blätter treiben.

. . .

Translations from the Italian and the German:

A. Z. Foreman

. . . . .

Poemas sobre la casa / la calle / la ciudad

Posted: October 10, 2014 Filed under: Anna Akhmatova, César Vallejo, Czeslaw Milosz, English, Héctor Pedro Blomberg, Konstantin Kavafis, Miguel Hernandez Gilabert, Octavio Paz, Spanish Comments Off on Poemas sobre la casa / la calle / la ciudadAna Ajmátova (1889-1966, Rusia)

Sótano del recuerdo

.

Es pura tontería que vivo entristecida

y que estoy por el recuerdo torturada.

No soy yo asidua invitada en su guarida

y allí me siento trastornada.

Cuando con el farol al sótano desciendo,

me parece que de nuevo un sordo hundimiento

retumba en la estrecha escalera empinada.

Humea el farol. Regresar no consigo

y sé que voy allí donde está el enemigo.

Y pediré benevolencia… pero allí ahora

todo está oscuro y callado. ¡Mi fiesta se acabó!

Hace treinta año se acompañaba a la señora,

hace treinta que el pícaro de viejo murió…

He llegado tarde. ¡Qué mala fortuna!

Ya no puedo lucirme en parte alguna,

pero rozo de las paredes las pinturas

y me caliento en la chimenea. ¡Qué maravilla!

a través del moho, la ceniza y la negrura

dos esmeraldas grises brillan

y el gato maulla. ¡Vamos a casa, criatura!

¿Pero dónde está mi casa y dónde mi cordura?

. . .

Héctor Pedro Blomberg (1889-1955, Argentina)

Las casas donde hemos vivido

.

¡Casas, donde vivimos

los días que se fueron para siempre!

Hoy hay rostros extraños,

se oyen vibrar desconocidas voces

y se escuchan los pasos de otras gentes

en las habitaciones donde un día,

enloquecidos de dolor, cerramos

las pupilas sin luz de nuestros muertos…

Ajenos corazones

laten bajo los techos familiares,

viven, lloran, esperan, sufren y aman,

lo mismo que nosotros

bajo la estrella roja de la vida.

Otras sombras divagan

por los patios de antaño;

otras lágrimas corren

detrás de los cristales,

cuando nieva la luna en la ventana;

el rumor de otros besos

ahuyentan nuestras sombras

en esas casas donde ayer vivimos.

Allí, en los aposentos olvidados,

donde bendijo Dios nuestros amores,

donde mecimos, trémulos, las cunas

y creímos morir junto a los féretros;

allí se ha quedado algo de nosotros,

de los días que huyeron para siempre;

amor, dolor, ensueño y esperanza,

recuerdo y juventud…

Nuestros ojos se nublan

cuando pasamos por las viejas casas

y las poblamos con las cosas muertas

que sólo viven en nosotros mismos. . .

Esos extraños rostros,

voces desconocidas,

esas vidas ajenas y lejanas…

¡Cómo nos hacen daño!

. . .

Miguel Hernandez Gilabert (1910-1942, España)

Poema No. 50

.

Mi casa contigo era

la habitación de la bóveda.

Dentro de mi casa entraba

por ti la luz victoriosa.

Mi casa va siendo un hoyo.

Yo no quisiera que toda

aquella luz se alejara

vencida, desde la alcoba.

Pero cuando llueve, siento

que las paredes se ahondan

y reverdecen los muebles,

rememorando las hojas.

Mi casa es una ciudad

con la puerta a la aurora,

otra más grande a la tarde,

y a la noche, inmensa, otra.

Mi casa es un ataúd,

bajo la lluvia redobla

y ahuyenta las golondrinas

que no la quisieron torva.

En mi casa falta un cuerpo.

Dos en nuestra casa sobran.

. . .

César Vallejo (1892-1938, Perú)

No vive ya nadie…

.

– No vive ya nadie en la casa – me dices; todos se han ido. La sala el dormitorio, el patio,

yacen despoblados. Nadie ya queda, pues que todos han partido.

Y yo te digo. Cuando alguien se va, alguien queda. El punto por donde pasó un hombre, ya no esta solo.

Unicamente está solo, de soledad humana, el lugar por donde ningún hombre ha pasado. Las casas nuevas

están mas muertas que las viejas, por que sus muros son de piedra o de acero, pero no de hombres. Una

casa viene al mundo, no cuando la acaban de edificar, sino cuando la empiezan a habitarla. Una casa vive

únicamente de hombres, como una tumba. Sólo que la casa se nutre de la vida del hombre, mientras que la

tumba se nutre de la muerte del hombre. Por eso la primera está de piie, mientras que la segunda está tendida.

Todos han partido de la casa, en realidad, pero todos se han quedado en verdad. Y no es el recuerdo de ellos lo que

queda, sino ellos mismos. Y no es tampoco que ellos queden en la casa, sino que continúan por la casa. Las funciones y

los actos se van de la casa en tren o en avión o a caballo, a pie o arrastrándose. Lo que continua en la casa es el

órgano, la gente en gerundio y en círculo. Los pasos se han ido, los besos, los perdones, los crímenes. Lo que continúa

en la casa es el pie, los labios, los ojos, el corazón. Las negaciones y las afirmaciones, el bien y el mal, se han

dispersado. Lo que continúa en la casa, es el sujeto del acto.

. . .

Czeslaw Milosz (1911-2004, Lituania/Polonia)

Pórtico

.

Bajo el pórtico de piedra esculpida

al sol entre claridad y sombra,

casi sereno. Pensando con alivio: esto permanecerá aquí

mientras, tan frágil, desaparezca el cuerpo

y de pronto no haya nadie.

palpando la porosidad del muro. Asombrado,

porque mi propio declina acepto tranquilo

aunque no debiera. ¿Qué hay entre tú y yo, tierra?

¿Qué tengo en común con tus paredes, donde las bestias taciturnas

pastaban antes del diluvio, sin levantar las cabezas?

¿Qué tengo en común con tu irrevocable renacer?

¿De dónde, pues, esta benévola melancolía?

¿Acaso porque es inútil la ira?

. . .

Octavio Paz (1914-1998, México)

La Calle

.

Es una calle larga y silenciosa.

Ando en tinieblas y tropiezo y caigo

y me levanto y piso con pies ciegos

las piedras mudas y las hojas secas

y alguien detrás de mí también las pisa:

si me detengo, se detiene;

si corro, corre. Vuelvo el rostro: nadie.

Todo está oscuro y sin salida,

y doy vueltas en esquinas

que dan siempre a la calle

donde nadie me espera ni me sigue,

donde yo sigo a un hombre que tropieza

y se levanta y dice al verme: nadie.

Constantino Cavafis (1863-1933, poeta griego-egipcio)

La Ciudad (1911)

.

Dijiste:

” Iré a otro país, veré otras playas;

buscaré una ciudad mejor que ésta.

Todos mis esfuerzos son fracasos

y mi corazón como muerto, está enterrado.

¿ por cuánto tiempo más estaré contemplando estos despojos?

A donde vuelvo la mirada,

veo sólo las negras ruinas de mi vida,

aquí donde tantos años pasé, destruí y perdí.”

No encontrarás otro país ni otras playas,

llevaras por doquier y a cuestas tu ciudad;

caminarás las mismas calles,

envejecerás en los mismos suburbios,

encanecerás en las mismas casas.

Siempre llegarás a esta ciudad;

no esperes otra,

no hay barco ni camino para ti.

Al arruinar tu vida en esta parte de la tierra,

la has destrozado en todo el universo.

. . . . .

John Brack y T.S. Eliot: pinturas + poemas

Posted: October 4, 2014 Filed under: English, Spanish, T. S. Eliot Comments Off on John Brack y T.S. Eliot: pinturas + poemasT.S. Eliot (poeta anglo-estadounidense, 1888-1965)

Preludios 1-4 (1917)

.

I

En los pasadizos, se establece la tarde del invierno

con olor a filete,

Las seis en punto.

Colillas de los días humeantes.

Y ahora un chaparrón

ventoso arremolina entre sus pies

los residuos mugrientos

de hojarasca marchita

y periódicos volados de solares vacíos.

Los chaparrones baten

persianas rotas, chimeneas,

y en la esquina de la calle

un solitario caballo de tiro piafa y bufa.

Y se encienden entonces las farolas.

II

La mañana recobra su conciencia

de los tenues y rancios

olores de cerveza que provienen

del serrín pisoteado en las calles

por todos esos pies

fangosos que se agolpan

en los madrugadores kioscos de café.

Con las otras mascaradas

que hace suyas el tiempo,

uno piensa en todas esas manos

que levantan persianas deslustradas

en un millar de cuartos de alquiler.

III

Arrojaste la manta de la cama,

te tumbaste de espaldas y esperaste,

adormilada, viste de qué modo la noche revelaba

el millar de sórdidas imágenes,

titilantes en el techo,

que constituían tu alma.

Y cuando el mundo entero volvió

y la luz se filtro sigilosa

por las contraventanas

y oíste a los gorriones en las cornisas,

tuviste una visión tal de la calle

que la calle difícilmente entiende;

sentada al borde de la cama, enrollaste

los bigudíes de tu pelo, o te masajeaste las plantas

amarillas de los pies

con las palmas sucias de tus manos.

IV

Su alma tensamente se alargaba

a través de los cielos

desvanecidos detrás de una manzana de edificios,

o bien con pies urgentes caminaba

a las cuatro, a las cinco y a las seis;

y cortos y cuadrados dedos

que rellenaban pipas de fumar,

periódicos vespertinos, y ojos

seguros de unas ciertas certidumbres,

la conciencia de una calle ennegrecida

impaciente por apropiarse del mundo,

Movido soy por quimeras que se enroscan

en torno a esas imágenes, y se adhieren a ellas:

la noción de algo infinitamente amable

que infinitamente sufre.

Pásate la mano por la boca, y ríe;

los mundos dan vueltas como ancianas mujeres

que recogen la leña en los derribos.

.

Traducción de Felipe Benítez Reyes

. . .

T.S. Eliot (Anglo-American poet, 1888-1965)

Preludes 1-4 (1917)

.

I

The winter evening settles down

With smell of steaks in passageways.

Six o’clock.

The burnt-out ends of smoky days.

And now a gusty shower wraps

The grimy scraps

Of withered leaves about your feet

And newspapers from vacant lots;

The showers beat

On broken blinds and chimneypots,

And at the corner of the street

A lonely cab-horse steams and stamps.

And then the lighting of the lamps.

II

The morning comes to consciousness

Of faint stale smells of beer

From the sawdust-trampled street

With all its muddy feet that press

To early coffee-stands.

With the other masquerades

That times resumes,

One thinks of all the hands

That are raising dingy shades

In a thousand furnished rooms.

III

You tossed a blanket from the bed

You lay upon your back, and waited;

You dozed, and watched the night revealing

The thousand sordid images

Of which your soul was constituted;

They flickered against the ceiling.

And when all the world came back

And the light crept up between the shutters

And you heard the sparrows in the gutters,

You had such a vision of the street

As the street hardly understands;

Sitting along the bed’s edge, where

You curled the papers from your hair,

Or clasped the yellow soles of feet

In the palms of both soiled hands.

IV

His soul stretched tight across the skies

That fade behind a city block,

Or trampled by insistent feet

At four and five and six o’clock;

And short square fingers stuffing pipes,

And evening newspapers, and eyes

Assured of certain certainties,

The conscience of a blackened street

Impatient to assume the world.

I am moved by fancies that are curled

Around these images, and cling:

The notion of some infinitely gentle

Infinitely suffering thing.

Wipe your hand across your mouth, and laugh;

The worlds revolve like ancient women

Gathering fuel in vacant lots.

. . .

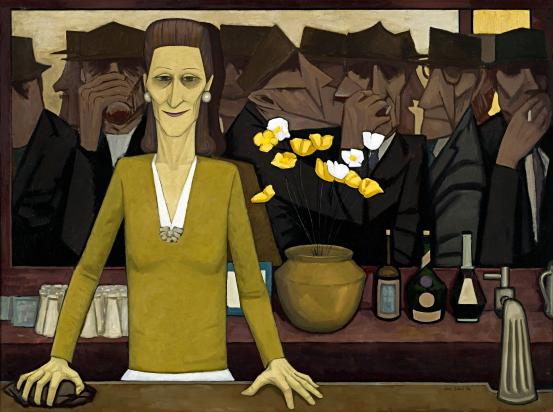

John Brack (1920-1999) fue un pintor australiano, nacido en Melbourne. Registró con sus pinturas de los años 50 “El Sueño australiano” – y lo mostró en la luz deprimante del invierno melbournense. Su grande fuente poética: Los Preludios de T.S. Eliot.

. . .

“Melburnian” Helen Bordeaux – from her Objects of Whimsy website, 2012:

“I’m not sure but when I was young I visited the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne and fell in love with a painting. I remember it being different from the other works. It was a streetscape holding a sea of faces. There was nothing pretty about the imagery; the faces of tobacco-stained complexions and haughty expressions were a dramatic contrast to the richly coloured landscape that surrounded it.

The painting was Collins St., 5 p.m., by John Brack (1920-1999).

Thirty years later I am living that painting – I live in Melbourne. Winter in Melbourne is just as Brack depicted: cold and grey, and there is a certain afternoon light unique to Melbourne that occurs when the sun shines behind thick grey clouds causing a tobacco-coloured hue to colour the sky and all that exists underneath it.

John Brack was a realist of the human condition, when post-War humans became the machine of industry, toiling fodder driving prosperity. How glad I am Brack documented these intriguing snapshots of ordinary life during the 1950s and 60s in Melbourne, Australia. This painting and other works of John Brack describe Melbourne’s character with imagery. They’re intriguing, with dark notes that keep a certain electric energy running through the streets and veins of those people who choose to live here !”

Editor’s note: We have paired Brack’s paintings with Eliot’s poems because Brack once said in an interview that his reading of The Preludes had been the poetic inspiration for him to paint Collins St., 5 p.m.

. . .

Melbourne Today…..