Inspired by Yeats: contemporary poets weigh in

Posted: March 17, 2016 Filed under: English, William Butler Yeats | Tags: Poems for Saint Patrick's Day Comments Off on Inspired by Yeats: contemporary poets weigh in.

William Butler Yeats (1865-1939)

Hound Voice

.

Because we love bare hills and stunted trees

And were the last to choose the settled ground,

Its boredom of the desk or of the spade, because

So many years companioned by a hound,

Our voices carry; and though slumber-bound,

Some few half wake and half renew their choice,

Give tongue, proclaim their hidden name: ‘Hound Voice.’

.

The women that I picked spoke sweet and low

And yet gave tongue. ‘Hound Voices’ were they all.

We picked each other from afar and knew

What hour of terror comes to test the soul,

And in that terror’s name obeyed the call,

And understood, what none have understood,

Those images that waken in the blood.

Some day we shall get up before the dawn

And find our ancient hounds before the door,

And wide awake know that the hunt is on;

Stumbling upon the blood-dark track once more,

Then stumbling to the kill beside the shore;

Then cleaning out and bandaging of wounds,

And chants of victory amid the encircling hounds.

. . .

Margaret Atwood (born 1939)

Because We Love Bare Hills and Stunted Trees

.

Because we love bare hills and stunted trees

we head north when we can,

past taiga, tundra, rocky shoreline, ice.

.

Where does it come from, this sparse taste

of ours? How long

did we roam this hardscape, learning by heart

all that we used to know:

turn skin fur side in,

partner with wolves, eat fat, hate waste,

carve spirit, respect the snow,

build and guard flame?

.

Everything once had a soul,

even this clam, this pebble.

Each had a secret name.

Everything listened.

Everything was real,

but didn’t always love you.

You needed to take care.

.

We long to go back there,

or so we like to feel

when it’s not too cold.

We long to pay that much attention.

But we’ve lost the knack;

also there’s other music.

All we hear in the wind’s plainsong

is the wind.

. . .

William Butler Yeats

Vacillation

.

I

Between extremities

Man runs his course;

A brand, or flaming breath.

Comes to destroy

All those antinomies

Of day and night;

The body calls it death,

The heart remorse.

But if these be right

What is joy?

II

A tree there is that from its topmost bough

Is half all glittering flame and half all green

Abounding foliage moistened with the dew;

And half is half and yet is all the scene;

And half and half consume what they renew,

And he that Attis’ image hangs between

That staring fury and the blind lush leaf

May know not what he knows, but knows not grief.

III

Get all the gold and silver that you can,

Satisfy ambition, animate

The trivial days and ram them with the sun,

And yet upon these maxims meditate:

All women dote upon an idle man

Although their children need a rich estate;

No man has ever lived that had enough

Of children’s gratitude or woman’s love.

.

No longer in Lethean foliage caught

Begin the preparation for your death

And from the fortieth winter by that thought

Test every work of intellect or faith,

And everything that your own hands have wrought

And call those works extravagance of breath

That are not suited for such men as come

proud, open-eyed and laughing to the tomb.

IV

My fiftieth year had come and gone,

I sat, a solitary man,

In a crowded London shop,

An open book and empty cup

On the marble table-top.

While on the shop and street I gazed

My body of a sudden blazed;

And twenty minutes more or less

It seemed, so great my happiness,

That I was blessed and could bless.

V

Although the summer Sunlight gild

Cloudy leafage of the sky,

Or wintry moonlight sink the field

In storm-scattered intricacy,

I cannot look thereon,

Responsibility so weighs me down.

.

Things said or done long years ago,

Or things I did not do or say

But thought that I might say or do,

Weigh me down, and not a day

But something is recalled,

My conscience or my vanity appalled.

VI

A rivery field spread out below,

An odour of the new-mown hay

In his nostrils, the great lord of Chou

Cried, casting off the mountain snow,

‘Let all things pass away.’

.

Wheels by milk-white asses drawn

Where Babylon or Nineveh

Rose; some conquer drew rein

And cried to battle-weary men,

‘Let all things pass away.’

.

From man’s blood-sodden heart are sprung

Those branches of the night and day

Where the gaudy moon is hung.

What’s the meaning of all song?

‘Let all things pass away.’

VII

The Soul. Seek out reality, leave things that seem.

The Heart. What, be a singer born and lack a theme?

The Soul. Isaiah’s coal, what more can man desire?

The Heart. Struck dumb in the simplicity of fire!

The Soul. Look on that fire, salvation walks within.

The Heart. What theme had Homer but original sin?

VIII

Must we part, Von Hugel, though much alike, for we

Accept the miracles of the saints and honour sanctity?

The body of Saint Teresa lies undecayed in tomb,

Bathed in miraculous oil, sweet odours from it come,

Healing from its lettered slab. Those self-same hands perchance

Eternalised the body of a modern saint that once

Had scooped out pharaoh’s mummy. I – though heart might find relief

Did I become a Christian man and choose for my belief

What seems most welcome in the tomb – play a pre-destined part.

Homer is my example and his unchristened heart.

The lion and the honeycomb, what has Scripture said?

So get you gone, Von Hugel, though with blessings on your head.

. . .

Harry Clifton (born 1952)

Chez Jeanette

.

My fiftieth year had come and gone.

I sat, a solitary man,

In a crowded London shop…

– W.B. Yeats

.

And so do I, past fifty now,

In the gilt and mirror-glass

Of Chez Jeanette’s immigrant bar.

Wine, cassis, an overflow

Spilt on the table – marble

Like Yeats’ but more of a mess.

.

Behind the bottles on the shelf

A real, a transcendental self

Is hiding. Great Master,

Tell me, as you sat with your cup,

And grace came down like interruption,

Did these flakes of ceiling plaster

.

Also drown in your dregs?

The fallen angels, broken spirits

Told like tea-leaves, disinherited,

Sold into Egypt? Child-wives, pregnant,

Hide the future, keep it dark.

Splinter-groups of young Turks

.

Stand at the counter, arguing.

And the saucers of small change

Accumulate. The minutes, the hours,

If grace or visitation

Ever enter . . . A prostitute,

Bottom of the range,

.

Her hangdog client, middle-aged,

Go next door, to the short-time hotel.

In the hour that God alone sees,

We are all anonymities,

No-one finds us, we cannot be paged

In Dante’s Heaven, Swedenborg’s Hell

.

Or the visions of William Yeats.

And whether the hour is early or late

Or out of time, I do not know.

But for now, it comes down to this –

The marble top, the wine, cassis,

And the finite afterglow.

. . .

William Butler Yeats

The Folly of Being Comforted

.

One that is ever kind said yesterday:

“Your well-belovéd’s hair has threads of grey,

And little shadows come about her eyes;

Time can but make it easier to be wise

Though now it seems impossible, and so

All that you need is patience.”

Heart cries, “No,

I have not a crumb of comfort, not a grain.

Time can but make her beauty over again:

Because of that great nobleness of hers

The fire that stirs about her, when she stirs,

Burns but more clearly. O she had not these ways

When all the wild Summer was in her gaze.”

Heart! O heart! if she’d but turn her head,

You’d know the folly of being comforted.

. . .

Rita Ann Higgins (born 1955)

The Bottom Lash

.

One that is ever kind said yesterday:

My dearest dear,

your temples are starting to resemble

the contents of our ash bucket

on a wet day.

.

What’s with your eyelashes?

They grow more sparse by the tic tock.

Are you biting them off

or having them bitten off,

like the lovers do during intimacy

in the Trobriand islands?

.

You have no bottom lashes at all.

Personally, I wouldn’t be seen out

without my bottom lash.

A bare bottom lash is tantamount

to social annihilation.

.

A word to the wise, my dearest dear,

the next time you lamp the hedger

you might ask him to clip clop

your inner and outer nostril hairs.

It’s not a good look for a woman.

.

By the by, doteling,

I’ve noticed the veins on your neck

are bulging like billio

when a male of the species

walks into the room.

Is that a natural phenomenon

or is it a practised technique?

Up or down you’ll get no accolades for it,

nor for the black pillows

under your balding eyes.

Apart from that, my dearest dear,

your beauty is second to none.

. . .

The above poems by Atwood, Clifton and Higgins, first appeared in The Irish Times (September 2015).

For other poems by W.B. Yeats (including translations into Spanish) click on the link:

https://zocalopoets.com/2012/03/17/poems-for-saint-patricks-day-love-and-the-poet-poemas-para-el-dia-de-san-patricio-amor-y-el-poeta/

. . . . .

Cinco poetas irlandeses: Cannon, Sheehan, Níc Aodha, Ní Chonchúir, Bergin

Posted: March 17, 2016 Filed under: A FEW FAVOURITES / UNA MUESTRA DE FAVORITOS, Cinco poetas irlandeses, English, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: Poetisas irlandesas Comments Off on Cinco poetas irlandeses: Cannon, Sheehan, Níc Aodha, Ní Chonchúir, BerginMoya Cannon (nac. 1956, Dunfanaghy, Condado de Donegal)

Olvidar los tulipanes

.

Hoy en la terraza

él está señalando con el bastón,

está preguntando:

¿Cuál es el nombre de esas flores?

Vacacionando en Dublín en los sesenta

ha comprado los cinco bulbos originales por una libra.

Los ha plantado, los ha fertilizado durante treinta y cinco años.

Los dividió, los almacenaba en el cobertizo sobre alambrada,

listos para plantar en hileras rectas

con sus corolas intensas de rojo y amarillo.

.

Tesoros transportados en galeones, tres siglos antes,

desde Turquía hasta Amsterdam.

Ahora es abril y ellos se balancean con el viento del condado Donegal,

encima de las hojas esbeltas de los claveles que todavía duermen.

.

Fue un hombre que cavaba surcos correctos y que recogió grosellas negras;

que enseñó a hileras de niños las partes de la oración, tiempos y declinaciones

debajo de un mapamundi de tela agrietada.

Y le encantaba enseñar el cuento de Marco Polo y de sus tíos que,

zarrapastrosos después de diez años de viaje,

volvían a casa pues rajaron el forro de sus chamarras

y se desparramaron los rubies de Catay.

.

Ahora, perdiendo primero los nombres,

él está de pie junto a su lecho de flores, preguntando:

¿Tú, cómo llamas a esas flores?

. . .

Moya Cannon (born 1956, Dunfanaghy, Co. Donegal)

Forgetting Tulips

.

Today, on the terrace, he points with his walking-stick and asks:

What do you call those flowers?

On holiday in Dublin in the sixties

he bought the original five bulbs for one pound.

He planted and manured them for thirty-five years.

He lifted them, divided them,

stored them on chicken wire in the shed,

ready for planting in a straight row,

high red and yellow cups–

.

treasure transported in galleons

from Turkey to Amsterdam, three centuries earlier.

In April they sway now, in a Donegal wind,

above the slim leaves of sleeping carnations.

.

A man who dug straight drills and picked blackcurrants;

who taught rows of children parts of speech,

tenses and declensions

under a cracked canvas map of the world–

who loved to teach the story

of Marco Polo and his uncles arriving home,

bedraggled after ten years journeying,

then slashing the linings of their coats

to spill out rubies from Cathay–

.

today, losing the nouns first,

he stands by his flower bed and asks:

What do you call those flowers?

. . .

Eileen Sheehan (nac. 1963, Scartaglin, Condado de Kerry)

Donde tú estás

.

Tú te tumbas en cualquiera cama,

te tumbas en el fondo, y el cojín acepta

el peso de tu cabeza,

el colchón recibiendo tu cuerpo como el invitado anhelado.

Te mueves durante el reposo

y las sábanas responden a tu giro;

las cobijas se adaptan y se amoldan a tu contorno.

El aire de la habitación toma el tiempo con tu respiración,

aceptando un desplazamiento mientras

yo rodeo las paredes de la ciudad que estás ‘soñando’.

.

Mis papeles

– están raídos y deshilachados al borde;

esa pintura que tengo de yo mismo – está nublándose,

manchada por la lluvia: mi cara está disolviendo enfrente de mí.

La noche te agarra en el sueño y estás aplacado por sus comodidades,

como las telas absorbiendo el sudor que despides.

Mis llantos van ignorados mientras estoy de pie por la verja,

implorando un acceso.

No hay nadie pedir ayuda mientras

te mudas una capa como te extiendes allí – roque;

mi solo testigo fiable.

.

(2009)

. . .

Eileen Sheehan (born 1963, Scartaglin, Co. Kerry)

Where you are

.

You lie down in whatever bed

you lie down in, the pillow accepting

the weight of your head, the mattress

receiving your body like a longed-for guest.

You move in your sleep and the sheets

react to your turnings, the blankets adjust,

shaping themselves to your outline.

The air

in the room keeps time with your breathing,

accepts being displaced while I circle the walls

of the city you dream.

My papers

are worn, frayed at the edges; that picture

I have of myself, clouding-over and spotted

with rain: my face is dissolving before me. The night

holds you in sleep, you are stilled by its comforts;

by the fabrics absorbing the sweat you expel.

My cries go unheeded as I stand at the gate,

pleading admittance. There is no one to turn to

as you shed a layer of your skin while you lie there,

dead to the world; my one reliable witness.

. . .

© 2009, Eileen Sheehan

. . .

Colette Níc Aodha (nac. 1967, Shrule, Condado de Mayo)

Ruinas

.

Buscando en los annales

por los acontecimientos que sucedieron

durante una época diferente;

recreando el Tiempo en las ruinas antiguas,

tocando la música de los ancianos,

pasos de baile de los ascendientes.

.

Anoche yo visité al lugar de mi padre

pero encontré la derrota de

una casa confeccionada de piel

mientras una otra ha estado dado forma

de abajo por sus huesos.

. . .

Colette Níc Aodha (born 1967, Shrule, Co. Mayo)

Ruins

.

Searching the annals

for events which took place

in a different era

Recreating time in old ruins

Playing ancient music

Dancing steps of our ancestors

Last night I visited my father’s place

but found a ruin of a house

crafted from skin

as another was shaped

below from his bone.

. . .

Nuala Ní Chonchúir (nac. 1970, Dublin)

Enojo

.

La luna está magullada esta noche.

Moreteada y hinchada está – pero

fanfarronea sobre nosotros

y jala júbilo a la rasca.

.

Luna de sebo, luna electrizante,

ella carga el cielo, y

es un foco descarado por encima de los árboles sazonados de escarcha.

.

Y aquí abajo, donde añoran nuestros ojos,

nos arrastramos a la iglesia en la plaza, y

hacemos las paces uno al otro – en el canto.

.

(2011)

. . .

Nuala Ní Chonchúir (born 1970, Dublin)

Anger

.

The moon is battered tonight, bruised and swollen,

but she swanks above us, bringing joy to the chill.

.

Tallow-moon, electric-moon, she shoulders the sky,

a brazen spotlight over trees salted with frost.

.

And down here, eyes aching, we creep to the church

on the square, make peace with each other in song.

. . .

from: The Juno Charm (2011)

. . .

Tara Bergin (nac. 1975, Dublin)

Bandera roja

.

Una vez uno de ellos me mostró cómo:

Giras esta mano (la derecha) para agarrar la culata.

Giras esta mano (la izquierda) para agarrar el cañon.

Tocó mi rodilla,

y oculté mi sorpresa;

pero ahora ha cambiado su canción.

.

36,37,38.9

.

Tengo fiebre, golondrina, estoy enferma.

Su bandera ondula roja,

la puedo oír desde mi ventana,

la escucho raída como un trapo rojo rasgado.

Ve por él, pajarito,

ve y diles ¡peligro! ¡peligro!

.

Lo llevaré como Vestido Dominical.

Lo llevaré cruzando el páramo

donde practican con sus pistolas.

.

38.9,37,36

.

Qué avergonzados estarán

de lastimar a una muchacha

joven y bonita como yo.

. . .

Tara Bergin (born 1975, Dublin)

Red Flag

.

Once one of them showed me how to:

You turn this (the right) hand to grasp the stock.

You turn this (the left) hand to grasp the barrel.

He touched my knee,

and I hid my surprise –

but now he’s changed his tune.

.

36,37,38.9

.

I’ve a fever, little sparrow, I am sick.

Their flag is flying red,

I can hear it from my window,

I hear it tattered like a torn red rag.

Go and get it, little bird,

go and tell them danger! danger!

.

I will wear it as my Sunday Dress.

I’ll wear it walking on the moor

where they practise with their guns.

.

38.9,37,36

.

How ashamed they’ll be

to hurt a young and pretty

girl like me.

. . .

Versiones en español del inglés por Alexander Best, excepto Bandera Rojo de Tara Bergin: traducido por Juana Adcock (nac. 1982, Monterrey, Mx.)

. . . . .

El Día Internacional de la Mujer: Poemas / International Women’s Day: Poems

Posted: March 5, 2016 Filed under: English, Fehmida Riaz, Halima Xudoyberdiyeva, Marge Piercy, Mina Loy, Qiu Jin, Spanish, Uzbek, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on El Día Internacional de la Mujer: Poemas / International Women’s Day: Poems. . .

Qiu Jin ( 秋瑾 1875-1907, Chinese revolutionary and poet)

Capping Rhymes With Sir Shih Ching From Sun’s Root Land

.

Don’t tell me women

are not the stuff of heroes –

I alone rode over the East Sea’s

winds for ten thousand leagues.

My poetic thoughts ever expand,

like a sail between ocean and heaven.

I dreamed of your three islands,

all gems, all dazzling with moonlight.

I grieve to think of the bronze camels,

guardians of China, lost in thorns.

Ashamed, I have done nothing;

not one victory to my name.

I simply make my war horse sweat.

Grieving over my native land

hurts my heart. So tell me:

how can I spend these days here?

A guest enjoying your spring winds?

. . .

Qiu Jin

Crimson Flooding into the River

(Translation from Mandarin: Michael A. Mikita III)

.

Just a short stay at the Capital

But it is already the mid-autumn festival

Chrysanthemums infect the landscape

Fall is making its mark

The infernal isolation has become unbearable here

All eight years of it make me long for my home

It is the bitter guile of them forcing us women into femininity

–We cannot win!

Despite our ability, men hold the highest rank

But while our hearts are pure, those of men are rank

My insides are afire in anger at such an outrage

How could vile men claim to know who I am?

Heroism is borne out of this kind of torment

To think that so putrid a society can provide no camaraderie

Brings me to tears!

. . .

Mina Loy (1882-1966, Anglo-American modernist poet)

Religious Instruction

.

This misalliance

follows the custom

for female children

to adhere to maternal practices

.

while the atheist father presides over

the prattle of the churchgoer

with ironical commentary from his arm-chair.

.

But by whichever

religious route

to brute

reality

our forebears speed us

.

there is often a pair

of idle adult

accomplices in duplicity

to impose upon their brood

.

an assumed acceptance

of the grace of God

defamed as human megalomania

.

seeding the Testament

with inconceivable chastisement,

.

and of Christ

who

come with his light

of toilless lilies

To say “fear

not, it is I”

wanting us to be fearful;

.

He who bowed the ocean tossed

with holy feet

which supposedly dead

.

are suspended over head

neatly crossed in anguish

wounded with red

varnish.

.

From these

slow-drying bloods of mysticism

mysteriously

the something-soul emerges

miserably,

.

and instinct (of economy)

in every race

for reconstructing débris

has planted an avenging face

in outer darkness.

…..

The lonely peering eye

of humanity

looked into the Néant

and turned away.

…..

Ova’s consciousness

impulsive to commit itself to justice

—to arise and walk

its innate straight way

out of the

accident of circumstance—

.

collects the levitate chattels

of its will and makes for the

magnetic horizon of liberty

with the soul’s foreverlasting

opposition

to disintegration.

.

So this child of Exodus

with her heritage of emigration

often

“sets out to seek her fortune”

in her turn

trusting to terms of literature

dodging the breeders’ determination

not to return “entities sent on consignment”

by their maker Nature

except in a condition

of moral

effacement;

Lest Paul and Peter

never

notice the creatures

ever had had Fathers

and Mothers.

.

They were disgraced in their duty

should such spirits

take an express passage

through the family bodies

to arrive at Eternity

as lovely as they originally

promised.

.

So on whatever days

she chose to “run away”

the very

street corners of Kilburn

close in upon Ova

to deliver her

into the hands of her procreators.

.

Oracle of civilization:

‘Thou shalt not live by dreams alone

but by every discomfort

that proceedeth out of

legislation’.

. . .

Mina Loy’s “Religious Instruction” from Lunar Baedeker and Times-Tables copyright The Jargon Society, 1958.

. . .

Mina Loy

No hay Vida o Muerte

.

No hay vida ni muerte,

sólo actividad.

Y en lo absoluto

no hay declive.

No hay amor ni deseo,

sólo la tendencia.

Quien quiera poseer

es una no entidad.

No hay primero ni último,

sólo igualdad.

Y quien quiera dominar

es uno más en la totalidad.

No hay espacio ni tiempo,

sólo intesidad.

Y las cosas dóciles

no tienen inmensidad.

.

Traducción del inglés: Michelle (de MujerPalabra)

. . .

Mina Loy

There is no Life or Death

.

There is no Life or Death

Only activity

And in the absolute

Is no declivity.

There is no Love or Lust

Only propensity

Who would possess

Is a nonentity.

There is no First or Last

Only equality

And who would rule

Joins the majority.

There is no Space or Time

Only intensity,

And tame things

Have no immensity.

. . .

Marge Piercy (nac.1936, EE.UU. / poeta, novelista, activista social)

Ser útil

.

Aquellos que yo amo mejor

se meten de cabeza en su trabajo

sin demorar en el bajío;

y nadan ahí fuera con brazadas seguras,

casi fuera de la vista.

Parecen ser nativos de eso elemento,

las cabezas negras lisas de focas

que rebotan como balones semi-sumergidos.

.

Me gustan los que se enjaezan: bueyes a una carreta pesada;

búfalos de agua que jalan con un temple masivo,

que tensan en el barro y la ciénaga para avanzar las cosas;

quienes que hacen lo que debe hacer, una y otra vez.

.

Quiero estar con la gente que se sumergir en la tarea;

que va en los sembríos para cosechar;

que trabaja en línea y que difunde los costales;

hombres y mujeres que no son generales del salón y desertores del deber

sino mueven en un ritmo común

cuando tiene que traer el alimento o necesita apagar el fuego.

.

La tarea del mundo es algo común, generalizado, como el barro.

Si hacemos una chapuza, embadurna las manos y se desmigaja al polvo.

Pero la cosa bien hecha

tiene la forma que complace, algo limpio, sencillo, evidente.

Ánforas griegos por el vino o el aceite,

y jarrones por el maíz del pueblo hopi,

están colocados en museos

– pero sabes que eran cosas hechas para utilizar.

El jarro llora por el agua a llevar

y la persona por el trabajo que es auténtico.

. . .

Del poemario Circles on the Water © 1982 / Traducción del inglés: Alexander Best

. . .

Marge Piercy (born 1936, American poet, novelist, social activist)

To be of use

.

The people I love the best

jump into work head first

without dallying in the shallows

and swim off with sure strokes almost out of sight.

They seem to become natives of that element,

the black sleek heads of seals

bouncing like half-submerged balls.

.

I love people who harness themselves, an ox to a heavy cart,

who pull like water buffalo, with massive patience,

who strain in the mud and the muck to move things forward,

who do what has to be done, again and again.

.

I want to be with people who submerge

in the task, who go into the fields to harvest

and work in a row and pass the bags along,

who are not parlour generals and field deserters

but move in a common rhythm

when the food must come in or the fire be put out.

.

The work of the world is common as mud.

Botched, it smears the hands, crumbles to dust.

But the thing worth doing well done

has a shape that satisfies, clean and evident.

Greek amphoras for wine or oil,

Hopi vases that held corn, are put in museums

but you know they were made to be used.

The pitcher cries for water to carry

and a person for work that is real.

. . .

Marge Piercy

Para las mujeres fuertes

.

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer esforzada.

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer que se sostiene de puntillas

y levanta unas pesas mientras intenta cantar Boris Godunov…

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer “manos a la obra”

limpiando el pozo negro de la historia.

Y mientras saca la porquería con la pala

habla de que no le importa llorar,

porque abre los conductos de los ojos…

Ni vomitar, porque estimula los músculos del estómago…

Y sigue dando paladas, con lágrimas en la nariz.

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer con una voz en la cabeza,

que le repite: “Te lo dije: sos fea, sos mala, sos tonta…

nadie más te va a querer nunca”.

“¿Por qué no eres femenina,

por qué no eres suave y discreta…

por qué no estás muerta…?“

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer empeñada

en hacer algo que los demás están empeñados en que no se haga.

Está empujando la tapa de plomo de un ataúd desde adentro.

Está intentando levantar con la cabeza la tapa de una alcantarilla.

Está intentando romper una pared de acero a cabezazos…

Le duele la cabeza.

La gente que espera a que haga el agujero,

le dice:”date prisa…¡eres tan fuerte…!”

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer que sangra por dentro.

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer que se hace a sí misma.

Fuerte cada mañana mientras se le sueltan los dientes

y la espalda la destroza.

“Cada niño, un diente…”, solían decir antes.

Y ahora “por cada batalla… una cicatriz”.

Una mujer fuerte es una masa de cicatrices

que duelen cuando llueve.

Y de heridas que sangran cuando se las golpea.

Y de recuerdos que se levantan por la noche

y recorren la casa de un lado a otro, calzando botas…

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer que ansía el amor

como si fuera oxígeno, para no ahogarse…

Una mujer fuerte es una mujer que ama con fuerza

y llora con fuerza…

Y se aterra con fuerza y tiene necesidades fuertes…

Una mujer fuerte es fuerte en palabras, en actos,

en conexión, en sentimientos…

No es fuerte como la piedra

sino como la loba amamantando a sus cachorros.

La fuerza no está en ella,

pero la representa como el viento llena una vela.

Lo que la conforta es que los demás la amen,

tanto por su fuerza como por la debilidad de la que ésta emana,

como el relámpago de la nube.

El relámpago deslumbra, llueve, las nubes se dispersan

Sólo permanece el agua de la conexión, fluyendo con nosotras.

Fuerte es lo que nos hacemos unas a otras.

Hasta que no seamos fuertes juntas

una mujer fuerte es una mujer fuertemente asustada…

. . .

Traducción del inglés: Desconocida/o

. . .

Marge Piercy

For strong women

.

A strong woman is a woman who is straining.

A strong woman is a woman standing

on tiptoe and lifting a barbell

while trying to sing Boris Godunov.

A strong woman is a woman at work

cleaning out the cesspool of the ages,

and while she shovels, she talks about

how she doesn’t mind crying, it opens

the ducts of the eyes, and throwing up

develops the stomach muscles, and

she goes on shoveling with tears

in her nose.

.

A strong woman is a woman in whose head

a voice is repeating: I told you so,

ugly, bad girl, bitch, nag, shrill, witch,

ballbuster, nobody will ever love you back,

why aren’t you feminine, why aren’t

you soft, why aren’t you quiet, why

aren’t you dead?

.

A strong woman is a woman determined

to do something others are determined

not be done. She is pushing up on the bottom

of a lead coffin lid. She is trying to raise

a manhole cover with her head, she is trying

to butt her way through a steel wall.

Her head hurts. People waiting for the hole

to be made say: hurry, you’re so strong.

.

A strong woman is a woman bleeding

inside. A strong woman is a woman making

herself strong every morning while her teeth

loosen and her back throbs. Every baby,

a tooth, midwives used to say, and now

every battle a scar. A strong woman

is a mass of scar tissue that aches

when it rains and wounds that bleed

when you bump them and memories that get up

in the night and pace in boots to and fro.

.

A strong woman is a woman who craves love

like oxygen or she turns blue choking.

A strong woman is a woman who loves

strongly and weeps strongly and is strongly

terrified and has strong needs. A strong woman is strong

in words, in action, in connection, in feeling;

she is not strong as a stone but as a wolf

suckling her young. Strength is not in her, but she

enacts it as the wind fills a sail.

.

What comforts her is others loving

her equally for the strength and for the weakness

from which it issues, lightning from a cloud.

Lightning stuns. In rain, the clouds disperse.

Only water of connection remains,

flowing through us. Strong is what we make

each other. Until we are all strong together,

a strong woman is a woman strongly afraid.

. . .

Fehmida Riaz (Pakistani poet who writes in Urdu / born 1946, Uttar Pradesh, India)

Come, Let us create a New Lexicon

.

Come let us create a new lexicon

Wherein is inserted before each word

Its meaning that we do not like

And let us swallow like bitter potion

The truth of a reality that is not ours

The water of life bursting forth from this stone

Takes a course not determined by us alone

We who are the dying light of a derelict garden

We who are filled with the wounded pride of self-delusion

We who have crossed the limits of self-praise

We who lick each of our wounds incessantly

We who spread the poisoned chalice all around

Carrying only hate for the other

On our dry lips only words of disdain for the other

We do not fill the abyss within ourselves

We do not see that which is true before our own eyes

We have not redeemed ourselves yesterday or today

For the sickness is so dear that we do not seek to be cured

But why should the many-hued new horizon

Remain to us distant and unattainable?

So why not make a new lexicon

If we emerge from this bleak abyss?

Only the first few footsteps are hard

The limitless expanses beckon us

To the dawning of a new day

We will breathe in the fresh air

Of the abundant valley that surrounds us

We will cleanse the grime of self-loathing from our faces.

To rise and fall is the game time plays

But the image reflected in the mirror of time

Includes our glory and our accomplishments

So let us raise our sight to friendship

And thus glimpse the beauty in every face

Of every visitor to this flower-filled garden

We will encounter ‘potentials’

A word in which you and me are equal

Before which we and they are the same

So come let us create a new lexicon!

. . .

Fehmida Riaz (Poetisa paquistaní, nac. 1946, Uttar Pradesh, India)

¡Ven, creemos un nuevo léxico!

.

¡Ven, creemos un nuevo léxico!

Uno donde el sentido de cada palabra

(que no nos gusta)

está insertado antes.

Y traguemos, como un veneno amargo,

la verdad de una realidad que no es nuestra.

El agua de vida que estalla de esta piedra

conduce un rumbo que nosotros solos no determinamos.

Nosotros – que son la luz murienda de un jardín decrépito;

nosotros – llenos del orgullo herido de nuestras ilusiones;

nosotros – que han superado los límites del autobombo;

nosotros – que lamen cada herida nuestra sin cesar;

nosotros – que hacen circular el cáliz envenenado,

nosotros – que llevan del uno al otro solo el odio,

y, sobre nuestras labias secas, nada más que palabras del desdén.

No llenamos el abismo en el interior;

no vemos con nuestros propios ojos lo que es auténtico en frente de nosotros;

no nos hemos redimido ayer o hoy;

porque nuestra enfermedad es tan preciada que no buscamos un tratamiento.

¿Pero por qué el horizonte de muchos tonos debe permanecernos como

remoto y inalcanzable?

.

Entonces, ¿Por qué no creamos un nuevo léxico?

Si resurgimos de este abismo austero,

solamente las primeras pisadas serán duras.

Las extensiones ilimitadas nos atraen al amanecer de un nuevo día.

Inhalaremos el aire fresco

del valle abundante que nos rodea.

Purificaremos de nuestras caras la mugre de aversión de uno mismo.

El vaivén, el auge y caída – son estos el juego que juega el Tiempo.

Pero la imagen que vemos en el espejo del Tiempo

incluye nuestra gloria también nuestros logros

– pues alcemos la mirada hasta la amistad,

por lo tanto entrever la belleza en cada rostro

de cada visitante en este jardín de muchas flores.

Nos encontraremos con ‘potenciales’,

una palabra en que tú y yo son equitativos;

una palabra en que nosotros y ellos son iguales.

Entonces,

¡Ven, creemos un nuevo léxico!

. . .

Traducción del inglés: Alexander Best

. . .

Fehmida Riaz

Chador and Char-Diwari

.

Sire! What use is this black chador to me?

A thousand mercies, why do you reward me with this?

.

I am not in mourning that I should wear this

To flag my grief to the world

I am not a disease that needs to be drowned in secret darkness

.

I am not a sinner nor a criminal

That I should stamp my forehead with its darkness

If you will not consider me too impudent

If you promise that you will spare my life

I beg to submit in all humility,

O Master of men!

In your highness’ fragrant chambers

lies a dead body—

Who knows how long it has been rotting?

It seeks pity from you

.

Sire, do be so kind

Do not give me this black chador—

With this black chador cover the shroudless body

lying in your chamber

.

For the stench that emanates from this body

Walks buffed and breathless in every alleyway

Bangs her head on every doorframe

Covering her nakedness

.

Listen to her heart-rending screams

Which raise strange spectres

That remain naked in spite of their chador.

Who are they ? You must know them, Sire.

.

Your highness must recognize them

These are the hand-maidens,

The hostages who are halal for the night.

With the breath of morning they become homeless

They are the slaves who are above

The half-share of inheritance for your

Highness’s off-spring.

.

These are the Bibis

Who wait to fulfill their vows of marriage

In turn, as they stand, row upon row

They are the maidens

On whose heads, when your highness laid a hand

of paternal affection,

The blood of their innocent youth stained the

whiteness of your beard with red.

In your fragrant chamber, tears of blood

life itself has shed

Where this carcass has lain

For long centuries, this body—

spectacle of the murder

of humanity.

.

Bring this show to an end now.

Sire, cover it up now—

Not I, but you need this chador now.

.

For my person is not merely a symbol of your lust:

Across the highways of life, sparkles my intelligence;

If a bead of sweat sparkles on the earth’s brow it is

my diligence.

.

These four walls, this chador I wish upon the

rotting carcass.

In the open air, her sails flapping, races ahead

my ship.

I am the companion of the New Adam

Who has earned my self-assured love.

. . .

Translation form Urdu: Rukhsana Ahmed

. . .

Halima Xudoyberdiyeva (born 1947, Boyovut, Uzbekistan)

Sacred Woman

(Translation from Uzbek: Johanna-Hypatia Cybeleia)

.

Your lovers have thrown flowers at your feet,

In solitude they have tasted honey from your lips,

And they have sold it to anyone at all,

You are sacred anyway, sacred woman.

.

First they came to fill your embrace, and told you to shine

You did not consent, woman, though people said the opposite

Unable to reach you, they turned their faces and called you bitter

You are sacred anyway, sacred woman.

.

You flutter your wings slowly and you lay your head down,

It’s been thousands of years, your eyes sparkle with tears,

A thousand and one criminals will hurt you with stones,

You are sacred anyway, sacred woman.

.

Though you come silently when summoned, though you come uselessly,

Though you come humbly to the drunken circle, though you come pleading to scoundrels,

Though you come oppressed to the scoundrels, though you come humbly,

You are sacred anyway, sacred woman.

.

In fact you’ll have amusements where you go,

Good and bad stories where you go,

You’ll have men like wild horses where you go,

You are sacred anyway, sacred woman.

.

Your silk-perfume body has the marks of stones,

Your bosom has the traces of heads that have leaned there,

You have the remnants of suns whose sun-fire has burned out,

You are sacred anyway, sacred woman.

. . .

Halima Xudoyberdiyeva

Water Flowing in Front of Me

.

To live in ease, to live in torment,

Not uselessly inclined away from you another sky,

My lifetime of hunting for hearts is over with,

There’s not even any thought of you going away.

.

Water flowing in front of me, my unappreciated water,

Enjoying myself for once in my life, I don’t feel relieved.

Ongoing sympathy, my secret water;

Until it dried up, I was not noticed.

.

I tell others don’t go away from me,

I go to find them in the dawn and evening time;

I offend others, telling them don’t show up;

I don’t even think anything about your going away.

.

I ran to others in cities, in towns,

You didn’t turn back or get sarcastic once.

Here I am, I’m the prey; here I am, I’ll go away,

Saying why didn’t you remind me once?

My mother, O my mother?!

. . .

Water Flowing in Front of Me in the original Uzbek:

.

Oldimdan Oqqan Suv

.

Yashamoq farog’at, yashamoq azob,

Bekorga egilmas Sizdan boshqa ko’k,

Ko’ngillarni ovlab umrim bo’pti sob,

Sizning ketishingiz xayolda ham yo’q.

.

Oldimdan oqqan suv, beqadr suvim,

Umrida bir yayrab, yozilmaganim.

Bor turishi shafqat, bori sir suvim,

To qurib qolguncha sezilmaganim.

.

Boshqalar yonimdan ketmasin debman,

Vaqt topib ularga boribman tong-kech,

Boshqalarga ozor yetmasin debman,

Sizga ham yetishin o’ylamabman hech.

.

Boshqalarga chopdim shahar, kentda man,

Bir qaytarib yo bir kesatmadingiz,

Manam g’animatman, manam ketaman,

Deb nechun bir bora eslatmadingiz?

Onam, onam-a?!

. . . . .

“A la Vida” / “Here’s to Life”: canción distintiva de Shirley Horn

Posted: February 29, 2016 Filed under: English, Spanish, Translator's Whimsy: Song Lyrics / Extravagancia del traductor: Letras de canciones traducidas por Alexander Best Comments Off on “A la Vida” / “Here’s to Life”: canción distintiva de Shirley HornA la Vida (letras: Phyllis Molinary / música: Artie Butler)

[canción distintiva de Shirley Horn (1934-2005)]

.

No tengo quejas ni arrepentimientos.

Aún creo en perseguir los sueños y hacer las apuestas.

Pero yo he aprendido ésto:

lo que tú das es todo que recibirás

– entonces dála una mejor vuelta en esta vida.

.

He tenido mi porción y he bebido más que bastante.

Y aunque estoy satisfecha, aún así tengo hambre de

ver lo que hay más adelante, más allá de la cresta de la colina

y hacerlo todo – de nuevo.

.

Pues, ¡a la Vida! y a todo el júbilo que nos jala.

Pues, ¡a la Vida! –– por los visionarios y sus sueños.

.

Raro es como vuela el Tiempo,

como el amor cambiará de hola acogedora hacia adiós triste;

como el amor te deja con los recuerdos que ya has memorizado

– para mantenerte caliente durante esos inviernos.

.

Mira, no hay “sí” en “ayer”,

¿Y quién comprende lo que lleve la mañana

– o lo que la mañana requise?

Pero siempre y cuando yo sea parte del juego pues quiero jugarlo

– por las risas, por la vida, y por el amor.

.

Entonces…¡a la Vida! y a todo el gozo que nos jala.

Sí, ¡a la Vida! –– por los soñadores y sus visiones.

Que soportares las tormentas, y

que mejorare todo lo que ya es bueno.

A la Vida… al Amor…

y…¡a ti!

. . .

Here’s to Life (lyrics by Phyllis Molinary / music by Artie Butler)

[as sung by Shirley Horn (1934-2005)]

.

No complaints and no regrets,

I still believe in chasing dreams and placing bets.

But I have learned that all you give is all you get;

So give it all you got.

.

I had my share, I drank my fill; and even though

I’m satisfied––I’m hungry still

To see what’s down another road, beyond the hill––

And do it all again.

.

So here’s to Life and all the joy it brings.

Here’s to Life––for dreamers and their dreams.

.

Funny how the time just flies,

How love can go from warm hellos to sad goodbyes,

And leave you with the memories you’ve memorized

To keep your winters warm.

For there’s no ‘yes’ in yesterday; and who knows what tomorrow brings or takes away? As long as I’m still in the game I want to play

For laughs, for life, for love.

.

So here’s to Life and every joy it brings.

Here’s to Life––for dreamers and their dreams.

.

May all your storms be weathered,

And may all that’s good get better.

Here’s to life, here’s to love, here’s to you.

.

May all your storms be weathered,

And may all that’s good get better.

Here’s to life, here’s to love, here’s to you!

. . .

Interpretación por Shirley Horn:

https://youtu.be/UTv3TONfTTQ

. . . . .

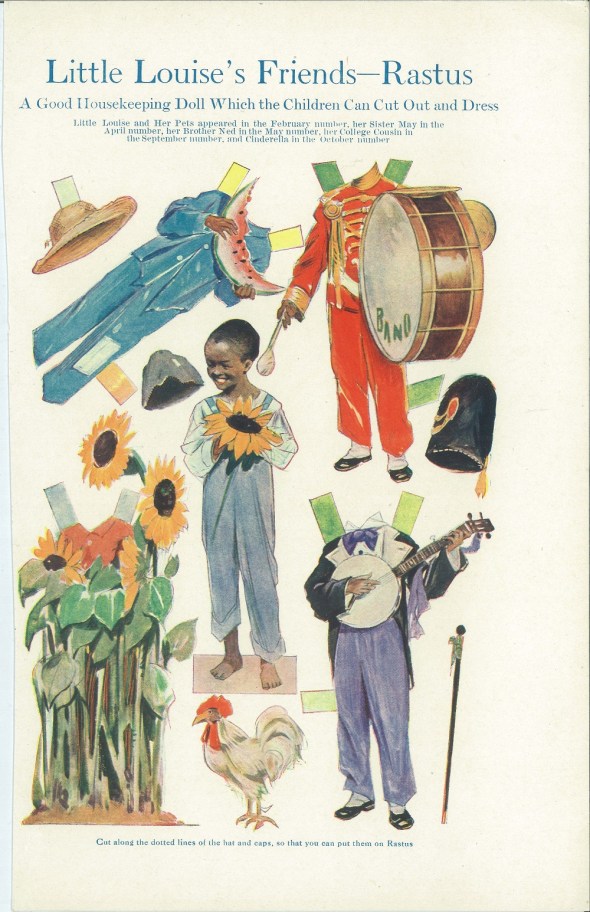

“As dearly as possible”: the Life of Ida B. Wells + poems by Lucille Clifton and Sterling A. Brown

Posted: February 29, 2016 Filed under: English, Lucille Clifton, Sterling A. Brown | Tags: Black History Month poems Comments Off on “As dearly as possible”: the Life of Ida B. Wells + poems by Lucille Clifton and Sterling A. Brown. . .

. . .

IDA B. WELLS (African-American journalist / civil-rights activist, 1862-1931)

.

Born to slave parents in Holly Springs, Mississippi in 1862, Ida Bell Wells grew up to become a gutsy journalist and a pioneer civil-rights activist who launched a virtual one-woman crusade against the vicious practice of Lynching (a murderous mob action taken by Whites in the decades following Emancipation as a form of intimidation and social control mainly of newly-free Blacks). In her early 20s, after asserting her place in but being forcibly removed from a railway car, Wells went on to co-own and write for a Memphis newspaper, The Free Speech, and to write passionate editorials which resulted in both death threats made upon her plus an act of arson that destroyed the business.

.

In school the young Ida favoured reading Shakespeare and The Bible, but at the age of 16 both of her parents died during a yellow-fever epidemic, leaving Ida to care for her six younger siblings. She obtained a teaching position at a rural school which paid her $25 per month. Later on, while her brothers remained in Holly Springs to train as carpenter’s apprentices, she moved with her sisters to her aunt’s home near Memphis, Tennessee. She began to teach in Shelby County, and also to attend Fisk University to broaden her teaching skills. It was in May of 1884 that the discriminatory railway-car incident occurred, and some time after that the name “Iola” began to appear in print in black publications as the author of articles about race and politics in the South. Miss Wells had been using the pseudonym for less than a year when, in 1887, she attended the National Afro-American Press Convention and was named the most prominent correspondent for the American black press.

.

Miss Wells did not shy away from controversy when she wrote for Free Speech. An anonymous article she penned was critical of Memphis’s separate but not-so-equal schools. She described rundown buildings and teachers who had received little more education than their students. Such revelations irked members of the local Board of Education. They also took issue with her claim that a member of the all-white board was having an affair with a black teacher. The ensuing uproar cost Wells her teaching job.

.

Yet she was now prepared to focus more fully on the newspaper and what its very name – Free Speech – entailed. She gradually earned enough to purchase a half-share of Free Speech, and while her partner, J.L. Fleming, handled business matters, Miss Wells handled the editorial and subscription departments, and under her leadership circulation increased from 1,500 to 4,000. Readers continued to rely on Free Speech to tackle controversial subjects, even when that meant speaking out against blacks as well as whites — even when it meant challenging the widely-accepted practice of Lynching.

.

When word reached Miss Wells that her friend Tom Moss, the father of her goddaughter, had been lynched, she learned a great deal more about the horrific practice than she could’ve imagined. Until that time, Wells, like most other people, knew that there were usually two reasons why a black man was lynched: he was accused of raping a white woman, or he was accused of killing a white man. Yet Moss’s “crime” was that he successfully competed with a white grocer, and for this reason he and his partners were murdered. Wells now understood that lynchings were not being used to weed out criminals but to enforce the ugly values of White Supremacy. So, in a series of scathing editorials in Free Speech, she urged Memphis’ black populace to boycott the city’s new streetcar line and to pack up their belongings and move out West if they could manage it.

.

African Americans heeded Wells’ pleas and began leaving Memphis by the hundreds. Two pastors of large black churches took their entire congregations to Oklahoma, and others soon followed. Those who stayed behind boycotted white businesses, creating financial hardships for commercial establishments as well as for the public transportation system. The city’s papers attempted to dissuade blacks from leaving by reporting on the hostile American Indians and dangerous diseases awaiting them out West. To counter their claims, Wells spent three weeks traveling in Oklahoma and published a firsthand account of the actual conditions. She was fast becoming a target for angry white men and women, so she was advised by her friends to ease up on her editorials. Instead, though, she decided to carry a pistol. In later years she was to recall: “[I had] already determined to sell my life as dearly as possible if attacked. I felt if I could take one lyncher with me, that might even up the score a little bit.”

.

After the murders of Moss and his partners, Wells spent some months investigating other lynchings across the South. Traveling from Texas to Virginia, she interviewed both whites and blacks in order to discern truth from rumour. Margaret Truman has written in her book Women of Courage: “To call this dangerous work is an understatement. Imagine a lone black woman in a small town in Alabama or Mississippi, asking questions that no one wanted to answer about a crime that half the whites in the town might’ve committed.” Miss Wells was to learn that rape was far from being the only crime lodged against victims of lynch mobs. Indeed, men had been lynched for “being saucy.”

.

In May of 1892, an article appeared in Free Speech stating that “nobody in this section believes the old thread-bare lie that Negro men assault white women. If Southern white men are not careful they will over-reach themselves and a conclusion will be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.” Many white citizens of Memphis did not appreciate the implication that some of their women might prefer the company of black men, and the editor of one Memphis newspaper declared that the “black wretch who had written that foul lie should be tied to a stake at the corner of Main and Madison Streets, a pair of tailor’s shears used on him, and he should then be burned at the stake.”

.

Wells, en route to New York City and unaware of the impact of her latest anonymous editorial, did not discover its fallout until reaching her destination. Fellow journalist T. Thomas Fortune, editor of the New York Age, informed her that a mob of white men had marched into the Free Speech offices, demolished the printing press, and set fire to the building. Fleming, Wells’s partner, had escaped just before the attack and was in hiding. The angry group had promised that both editors would be lynched if they ever again set foot again in Memphis. Wells received telegrams and letters from friends begging her not to return. They told her that there were instructions to kill her on sight.

.

And so, Miss Wells remained in New York and accepted a job from Fortune at the New York Age. Among the first stories she wrote for the newspaper was a front-page spread detailing names, dates, and locations of several dozen lynchings. In some cases, the lynchers were prominent members of society who could have easily gone through proper legal channels had there been actual evidence of their victims’ guilt.

.

That particular issue of the Age sold 10,000 copies, yet it reached a predominantly black audience — not the northern white progressives Wells knew she needed to move to action if she wanted to stop the brutalities of Lynching. In 1893, therefore, she embarked upon a speaking tour of the British Isles and Europe, and it was in those overseas nations that she found white people who were more receptive to her activist concerns. Via this circuitous route, Miss Wells’ message – with the help of various newspaper editors and organizations such as the London-based Anti-Lynching Committee and the Society of Brotherhood of Man – made its way back to the United States. Some American newspaper editorials continued to attack Wells, referring to her as “the slanderous and nasty-minded mulattress.” And she faced the opposition of both conservative whites and upper-class blacks who feared any threat to the security of their positions.

.

“Home” after her overseas speaking tour, Wells moved to Chicago in 1893 or 1894, and began working for The Conservator, a black newspaper founded and edited by a lawyer named Ferdinand Barnett. When blacks were excluded from participating in the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (held in Chicago), she teamed up with Barnett and Frederick Douglass to compile a booklet entitled “The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not Represented in the World’s Columbian Exposition.” Thousands of copies of it were distributed during the fair. Miss Wells also published A Red Record, which recounted three years’ worth of American lynchings, and in order to avoid any charges of bias, she gathered all of her data from white-published sources, primarily the Chicago Tribune.

.

In 1895, at the age of 33, Miss Wells married Barnett, who shared her passion for civil rights. They remained in Chicago, and Mrs. Wells-Barnett divided her time between raising four children and working on various causes: the anti-lynching crusade; establishing kindergartens in the black district of Chicago; and – with reformer Jane Addams – protesting successfully against a plan to segregate the city’s schools.

.

Ida Wells-Barnett – now a wife and mother – kept on speaking out against discrimination…

She denounced the restriction of blacks to the backs of buses and theatre balconies, plus their exclusion from organizations such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). In 1909, Wells-Barnett attended the conference of “radical” activists that led to the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Perhaps not surprisingly – given her feisty and energetic character – she resigned not long afterwards, frustrated that the organization was not committed enough to militant action. Some years earlier, she had quit the Afro-American Council in protest against Booker T. Washington and his policy of “accommodation”.

.

In the last decades of her passionate life, Wells-Barnett devoted most of her time and energy to various civic and political activities in Chicago. From 1913 until 1916, for instance, she worked as an adult probation officer. She also remained busy with club work and founded the first African-American women’s suffrage organization. She even ran for state senator in the 1930 elections, though she was easily defeated.

.

Imagine if Ida Wells-Barnett had been able to see into the future?

She might then have seen how much she influenced the civil-rights movement of the 1960s – and a new era in race relations – with her own battles against discrimination all those decades earlier. Ida Wells-Barnett died of kidney disease in 1931 at the age of sixty-nine. But she is remembered here and now in the 21st century as a courageous pioneer for truth and justice – and as an African-American woman of whom we should all be proud.

. . .

The above biographical essay and commentary has been edited for length. It first appeared in Americans Who Tell The Truth: Models of Courageous Citizenship © The Gale Group

. . .

Lynching as a subject for poetry: two examples from poets Lucille Clifton and Sterling Allen Brown:

.

. . .

Lucille Clifton (1936-2010)

The Photograph: A Lynching

.

Is it the cut glass

of their eyes

looking up toward

the new gnarled branch

of the black man

hanging from a tree?

.

Is it the white milk pleated

collar of the woman

smiling toward the camera,

her fingers loose around

a christian cross drooping

against her breast?

.

Is it all of us

captured by history into an

accurate album? Will we be

required to view it together

under a gathering sky?

. . .

Sterling A. Brown (1901-1989)

Let Us Suppose

.

Let us suppose him differently placed

In wider fields than these bounded by bayous

And the fringes of moss-hung trees

Over which, in lazy spirals, the carancros [carrion crows] soar and dip.

.

Let us suppose these horizons pushed farther,

So that his eager mind,

His restless senses, his swift eyes,

Could glean more than the sheaves he stored

Time and time again:

Let us suppose him far away from here.

.

Or let us, keeping him here, suppose him

More submissive, less ready for the torrent of hot Cajan speech,

The clenched fist, the flushed face,

The proud scorn and the spurting anger;

Let us suppose him with his hat crumpled in his hand,

The proper slant to his neck, the eyes abashed,

Let us suppose his tender respect for his honour

Calloused, his debt to himself outlawed.

.

Let us suppose him what he could never be.

.

Let us suppose him less thrifty

Less the hustler from early morning until first dark,

Let us suppose his corn weedy,

His cotton rusty, scantily fruited, and his fat mules poor.

His cane a sickly yellow

Like his white neighbour’s.

.

Let us suppose his burnt brick colour,

His shining hair thrown back from his forehead,

His stalwart shoulders, his lean hips,

His gently fused patois of Cajan, Indian, African,

Let us suppose these less the dragnet

To her, who might have been less lonesome

Less driven by Louisiana heat, by lone flat days,

And less hungry.

.

Let us suppose his full-throated laugh

Less repulsive to the crabbed husband,

Let us suppose his swinging strides

Less of an insult to the half-alive scarecrow

Of the neighbouring fields:

Let us suppose him less fermenting to hate.

.

Let us suppose that there had been

In this tiny forgotten parish, among these lost bayous,

No imperative need

Of preserving unsullied,

Anglo-Saxon mastery.

.

Let us suppose –

Oh, let us suppose him alive.

. . .

“Let Us Suppose” was first published in the September 1935 issue of Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life.

. . . . .

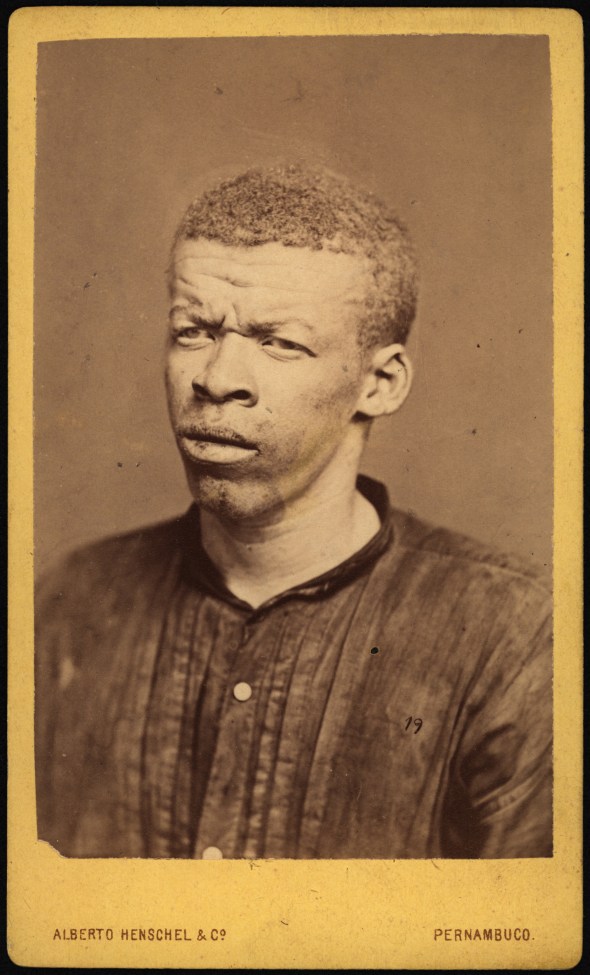

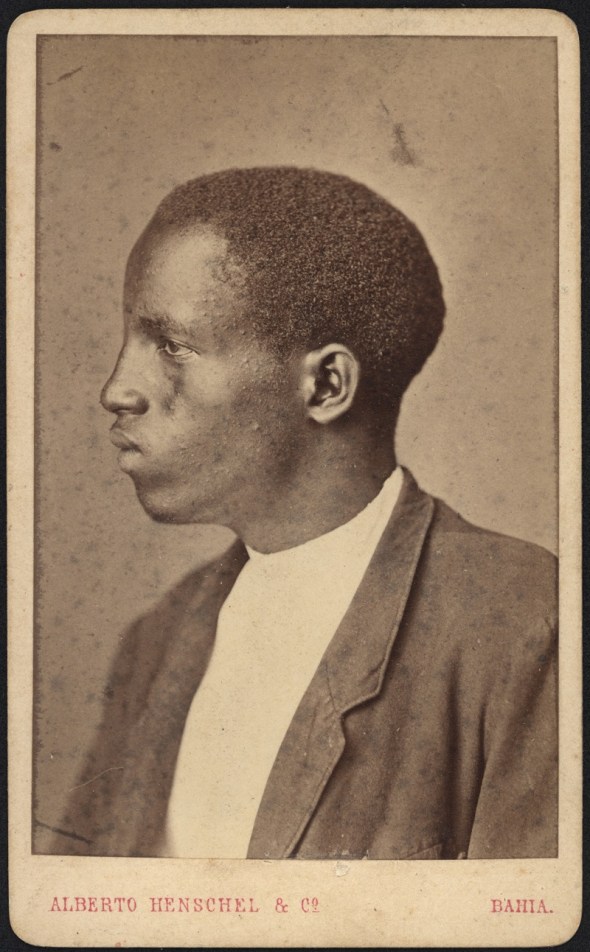

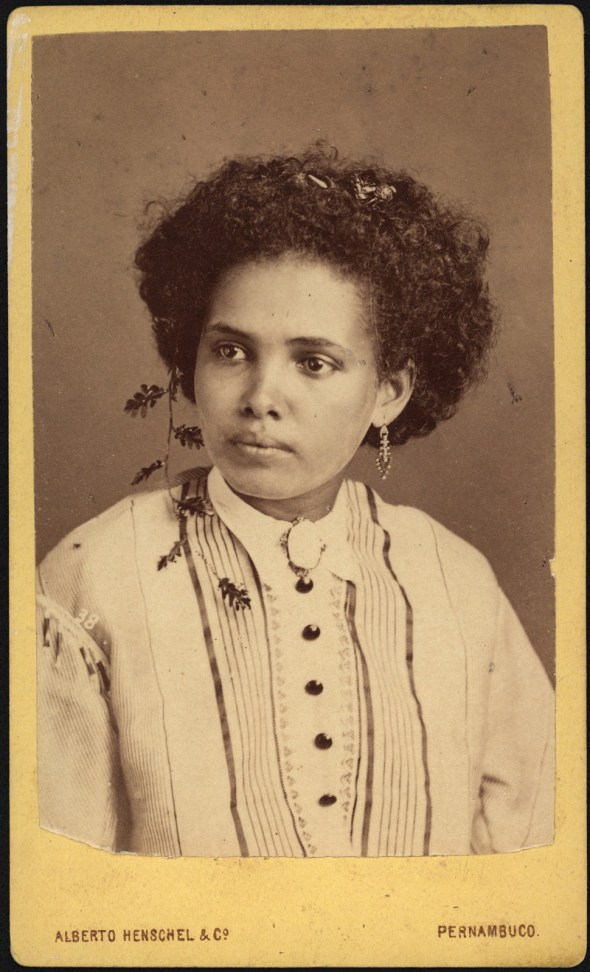

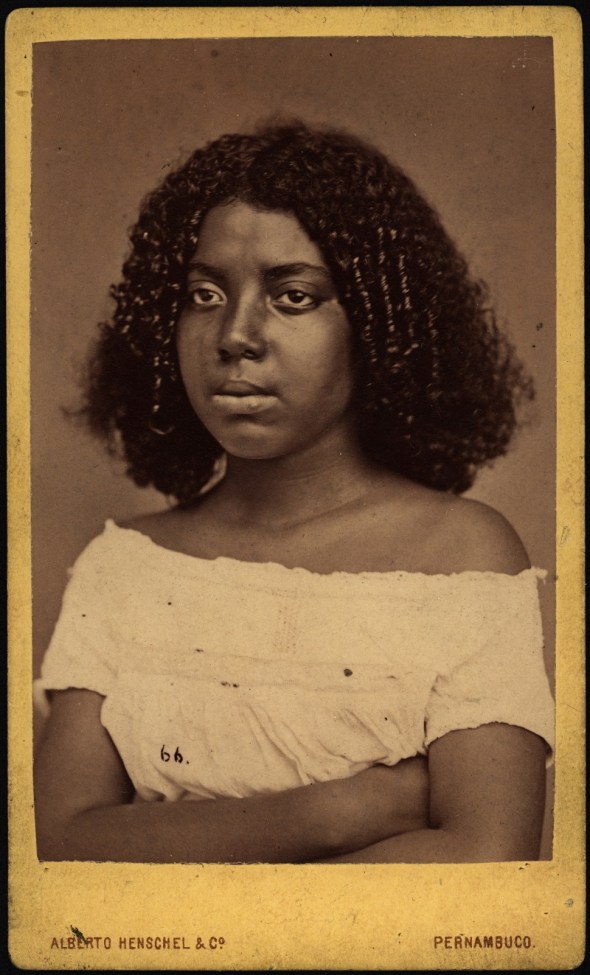

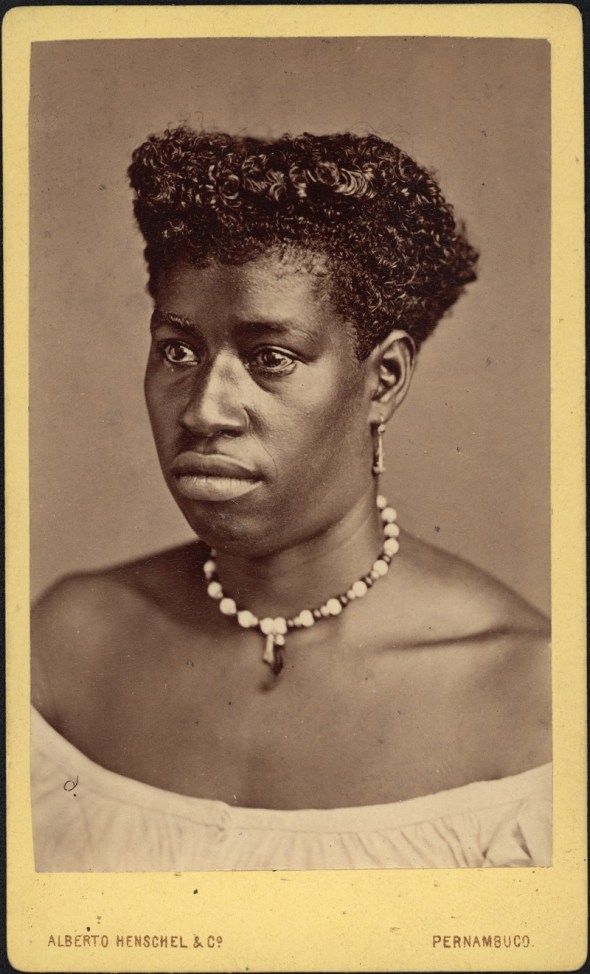

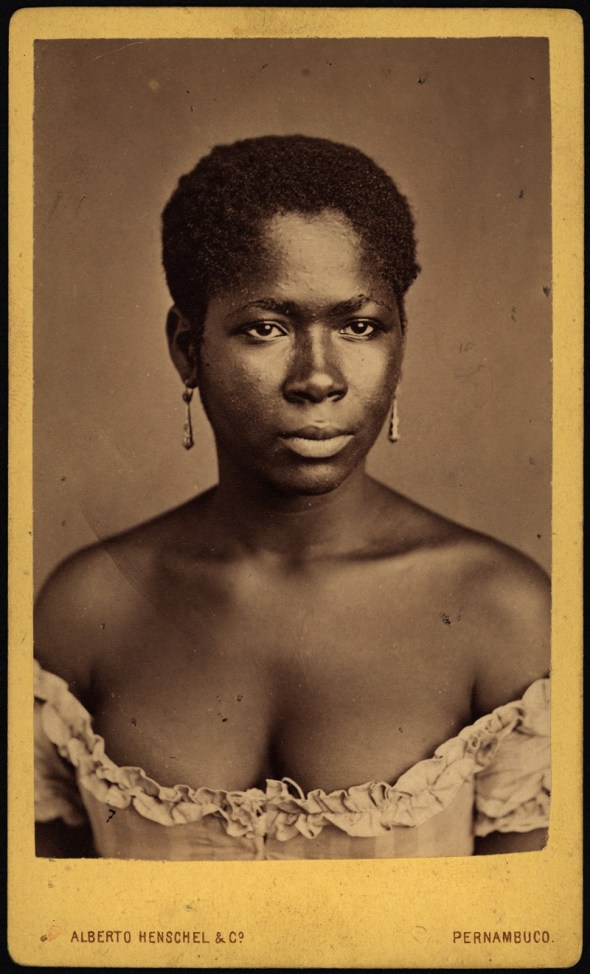

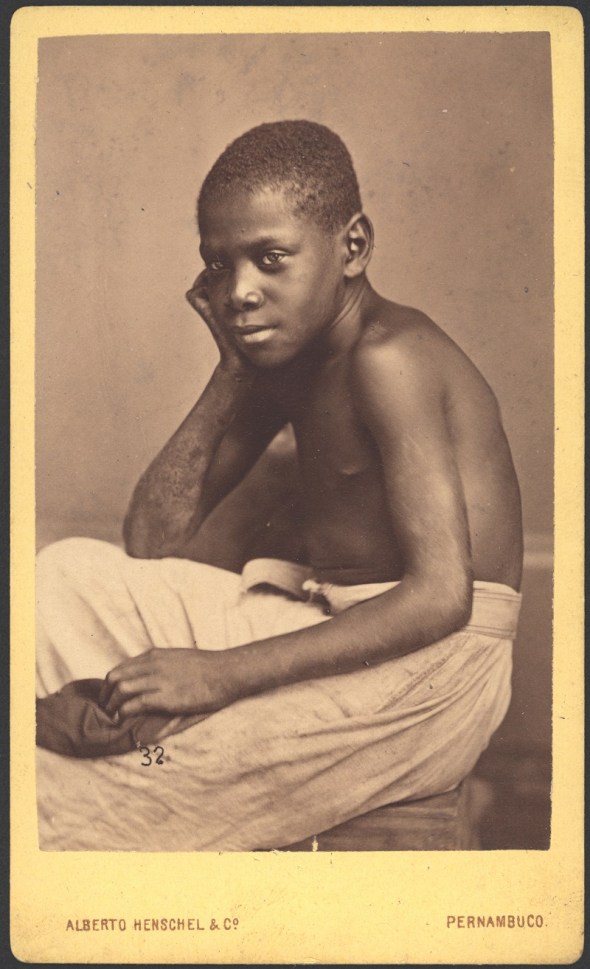

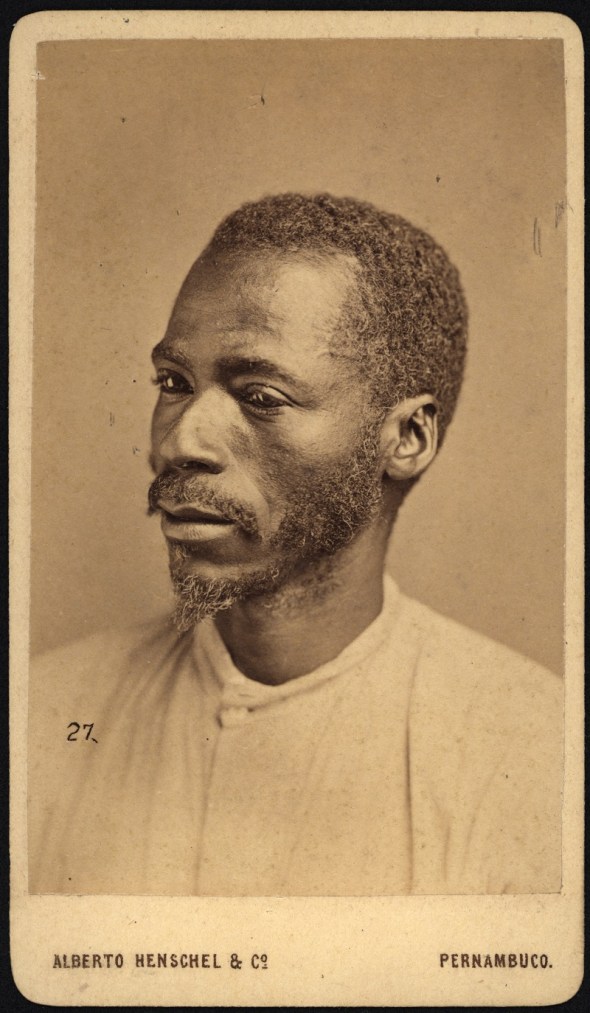

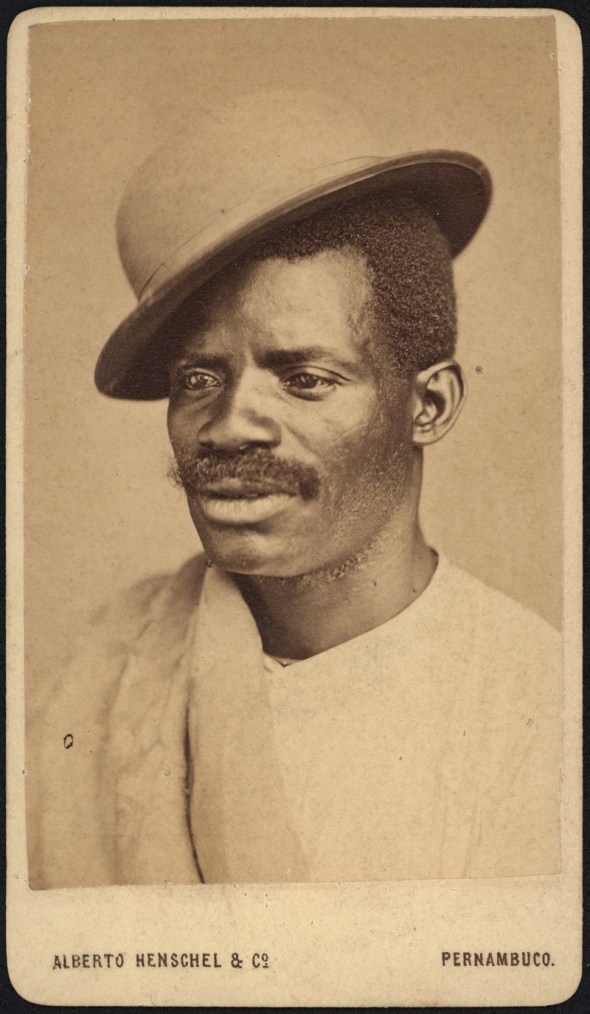

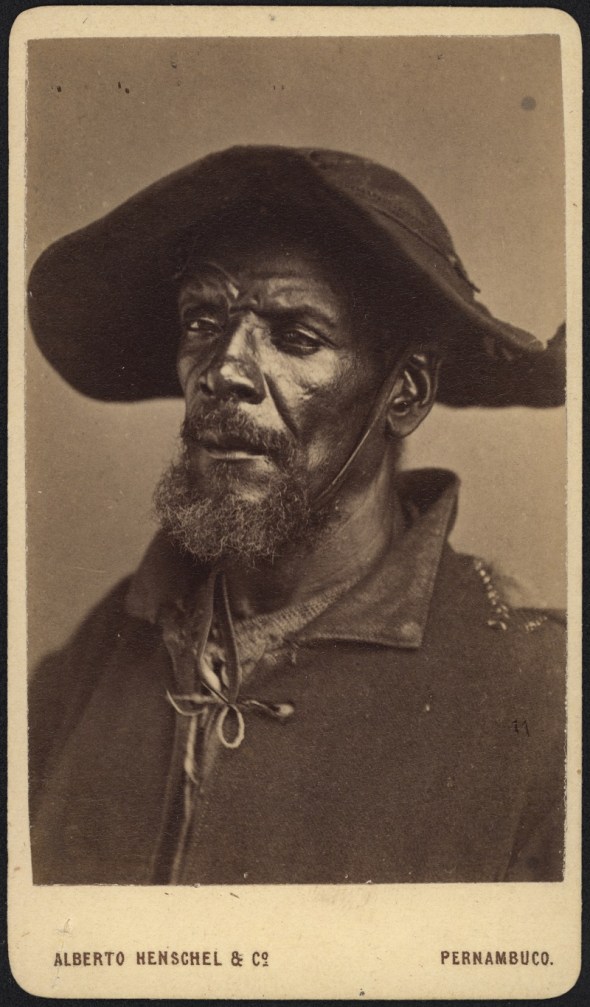

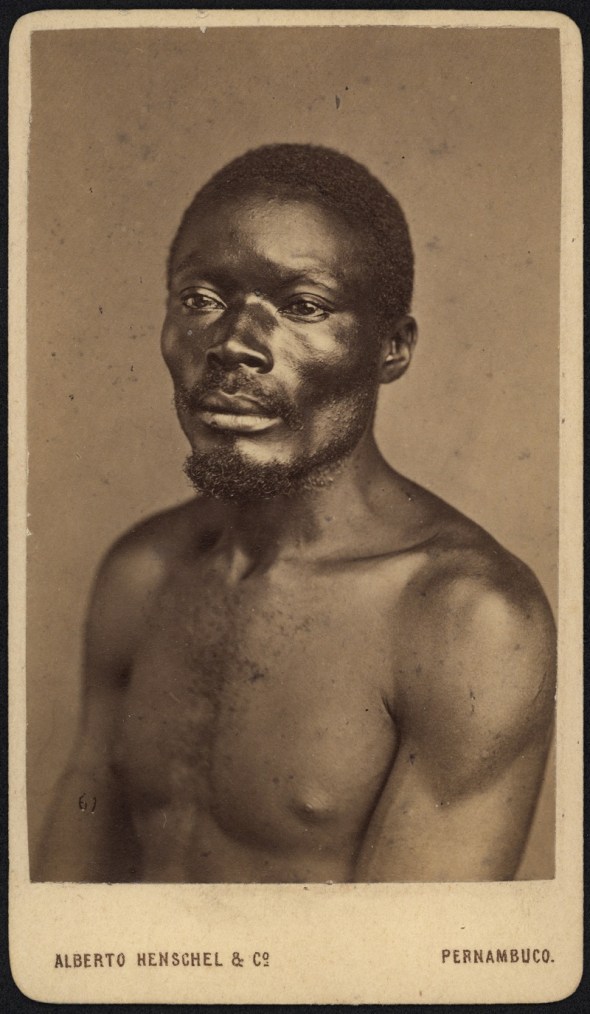

Alberto Henschel: 19th-century Brazilian photographer: Tipos negros / Black Types

Posted: February 25, 2016 Filed under: English, IMAGES, Portuguese | Tags: Black History Month photographs Comments Off on Alberto Henschel: 19th-century Brazilian photographer: Tipos negros / Black TypesAlberto Henschel (1827-1882) was a German-born Brazilian photographer from Berlin. An energetic, enterprising businessman, he established photography studios in the cities of Pernambuco, Bahia, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. While known as both a landscape photographer and, for some time Photographo da Casa Imperial (Photographer of the Royal House) during the reign of Pedro II, his main legacy has been his visual record of the social classes of Brazil. His portraits were often produced in the ‘carte de visite’ format, and included the nobility, wealthy tradesmen, the middle class and, most interestingly, Brazil’s black people – whether slaves or freemen/women. These portraits were taken during the decades before the Lei Áurea, the slavery-abolition law of 1888.

.

Alberto Henschel (Berlim, 1827 – Rio de Janeiro, 1882) foi um fotógrafo teuto-brasileiro, considerado o mais diligente empresário da fotografia no Brasil do século XIX. Sua principal contribuição à história

da fotografia no Brasil foi o registro fotográfico de todos os extratos sociais do Brasil oitocentista: retratos, geralmente no padrão carte-de-visite, foram tirados da nobreza, dos ricos comerciantes, da classe média e, mas certamente, dos negros – tantos livres como escravos (em um período ainda anterior à Lei Áurea.

.

. . . . .

Brazilian Women Poets (Cadernos Negros / “Black Notebooks”, 1997): new translations from the Portuguese: Rufino, da Silva, Evaristo, Ribeiro, Vieira, Alves, Fátima, Tadeu

Posted: February 25, 2016 Filed under: A FEW FAVOURITES / UNA MUESTRA DE FAVORITOS, Brazilian women poets: new translations, English, Portuguese | Tags: Black History Month poems, Brazilian women poets Comments Off on Brazilian Women Poets (Cadernos Negros / “Black Notebooks”, 1997): new translations from the Portuguese: Rufino, da Silva, Evaristo, Ribeiro, Vieira, Alves, Fátima, Tadeu.

Alzira Rufino (born 1949, Santos, São Paulo state)

POLICE REPORT

.

The black woman is not stopped

by this brutish thing

by this lukewarm discrimination

your strength is a secret

show your speech through your pores

your scream will echo in the city

they weed your dignity

as poisonous weeds

they hurt you with arrows commended

they experiment on you

your négritude – Blackness –

disturbs,

your whirlpool of forces drowns all around it

they don’t want your presence

they cross your name with absence

come, black woman,

be, black woman,

see, black woman –

after the storm

. . .

BOLETIM DE OCORRÊNCIAS

.

Mulher negra não para

por essa coisa bruta

por essa discriminação morna

tua força ainda é segredo

mostra tua fala nos poros

o grito ecoará na cidade

capinam como mato venenoso

a tua dignidade

ferem-te com flechas encomendadas

te fazem alvo de experiências

tua negritude

incomoda

teu redemoinho de forças afoga

não querem a tua presença

riscam teu nome com ausência

mulher negra, chega,

mulher negra, seja,

mulher negra, veja,

depois do temporal

. . .

Ana Célia da Silva (born in Salvador da Bahia)

JOE

(To my father)

.

Down the street

there goes Joe,

sad and tired

Joe’s the people

Joe is Joe

An urn-less fakir

A stage-less actor

A nameless acrobat

There goes Joe

No present

No future

And any past he gets

he tries to forget

At times he cries

He rarely laughs

He always thinks

he’ll leave

as a sad inheritance

for the future

the tightrope

the shack

the empty casserole

and a bread-less family

. . .

ZÉ

(Para meu pai)

.

Descendo a rua

lá vai o Zé,

triste e cansado

ele é o povo

ele é o Zé.

Faquir sem urna,

ator sem palco,

acrobata anônimo,

lá vai o Zé.

Não tem presente,

Não tem futuro,

se tem passado

tenta esquecer.

Às vezes chora,

bem pouco ri,

vive pensando

que vai deixar

de triste herança

para o futuro,

a corda bamba,

o barracão

marmita vazia

e família sem pão.

. . .

Conceição Evaristo (born 1946, Belo Horizonte)

IN WRITING…

.

In writing hunger

With empty-palmed hands

when the hole-stomach

expels famished desires

there is, in this demented movement

the dream-hoping

for any leftovers.

.

In writing cold

with the tip of my bones

caring in my body the tremor

of pain and shelterless-ness

there is, in this tense movement

the warmth-hoping

for any miserable little vest.

.

In writing pain,

alone,

searching for the resonance

of another in me

there is in this constant movement

the illusion-hoping

for our doubled consonance.

.

In writing life

fading and swimming

on departure’s test tube

there is, in this useless movement

the treacherous-hoping

for catching Time

and caressing eternity.

. . .

AO ESCREVER…

.

Ao escrever a fome

com as palmas das mão vazias

quando o buraco-estômago

expele famélicos desejos

há neste demente movimento

o sonho-esperança

de alguma migalha alimento.

.

Ao escrever o frio

com a ponta de meus ossos

e tendo no corpo o tremor

da dor e do desabrigo,

há neste tenso movimento

o calor-esperança

de alguma mísera veste.

.

Ao escrever a dor,

sozinha,

buscando a ressonância

de outro em mim

há neste constante movimento

a ilusão-esperaça

da dupla sonância nossa.

.

Ao escrever a vida

no tubo de ensaio da partida

esmaecida nadando,

há neste inútil movimento

a enganosa-esperança

de laçar o tempo

e afagar o eterno.

. . .

Esmeralda Ribeiro (born 1958, São Paulo)

LOVE’S ENIGMA

.

There is an island

There is ivory

There is an archipelago in me

.

I’m the same actress rehearsing

every day

the same love case

lived by a whisker.

.

Inside me

solitude dressed as a Harlequin

.

I’m that one that although full of bruises

makes her body like cinnamon

perfumed grass

for her negro to sleep

.

Inside me

Illusions drawn with Indian ink

.

I am that woman

trying to wake up sleeping beauties

but, inside, I am a princess

in profound lethargy.

.

Inside me

a warrior’s strength dressed in satin.

.

I am that one who at night

hides as a chameleon

eye’s pearly drops

in warm passion.

.

Inside me

lives at last the enigma of love.

.

I am that one which no verb translates

before the loneliness and the pain,

that one with insane behaviours

That’s me – the eternal

Mary Joanne.

. . .

ENIGMA DO AMOR

.

Há uma ilha

há marfim

há tristes arquipélagos em mim.

.

Sou a mesma atriz que ensaia

todos os dias

o mesmo caso de amor

vivido por um triz.

.

Dentro de mim

solidão vestida de Arlequim.

.

Sou aquela cheia de hematomas,

mas que faz do corpo relva

com aroma de canela

pro seu negro dormir.

.

Dentro de mim

ilusões traçadas à nanquim.

.

Sou aquela mulher

tentando despertar belas adormecidas

mas, no íntimo, sou a princesa

em profunda letargia.

.

Dentro de mim

força guerreira vestida de cetim.

Sou aquela que à noite

esconde como camaleão

gotas de pérolas d’olho

na cálida paixão.

.

Dentro de mim

enfim mora o enigma do amor.

.

Sou aquela que nenhum verbo traduz

diante da solidão e da dor

aquela que tem atitudes insanas

Esta sou eu, a eterna

Maria Joana.

.

Lia Vieira (born 1958, Rio de Janeiro)

EAGERNESS

.

In the memory blinks

images of remote times

and recent things

The air is heavy

always has been

There’s hunger in the world outside

There’s no eating.

There’s tiredness in the world here inside

There is big fear

something frightful

As if nothing might

ever sprout again.

There’s something deformed here inside

Madness that explodes

about to crash / soul made of glass

Maybe is the answer I’m waiting for

Maybe is my ego

egocentric, egotistic, which

– throbbing –

is eager for love.

. . .

ÂNSIA

.

Pisca a memória

imagens de tempos remotos

e também de coisas recentes.

O ar está pesado

tem estado

No mundo lá for a há fome.

Não se come.

No mundo cá dentro há cansaço.

Há um medo grande

uma coisa de susto.

Como se fosse acontecer

não brotar nunca mais.

Há algo disforme cá dentro.

Loucura que explode

prestes a estilhaçar / alma de vidro.

Talvez seja a resposta que espero…

Talvez seja apenas meu ego,

egocêntrico, egoísta, que,

latejante …

deseja amor.

. . .

Miriam Alves (born 1952, São Paulo)

INNER LANDSCAPE

.

The night breeds chords

the joyful star turns into a moon

a dream’s sonata rolls along the asphalt

.

A sleeping sky confuses itself

the sun shines over it with

a middle-of-the-night smile

dew splashes on the roofs

.

The sky’s face muddles

half nights, half days

a dawn rises

a playful child is born

wrapped in dawn’s early hours

.

Wake up, day!

There’s eagerness for hope!

. . .

PAISAGEM INTERIOR

.

A madrugada respira acordes

estrela brincalhona enluará

sonata dum sonho rola asfalto

.

O céu todo em sono confunde-se

o sol ilumina-o com

um sorriso madrugada

respinga orvalho nos telhados

.

A face do céu confunde-se

meio em noites, meio em dias

desponta uma autora

nasce uma criança brincalhona

toda envolta em madrugada.

.

Acorda dia!

há fome de esperança!

. . .

Sônia Fátima (born 1951, Araraquara, São Paulo state)

THE IT

.

The night brought me it:

I don’t know if I call it

I don’t know if I contradict it

or if I just don’t care about

the Benedict

. . .

O DITO

.

A noite trouxe-me isto:

não sei se ligo para o dito

não sei se desdigo o dito

ou simplesmente não ligo

para o Benê-dito

. . .

Teresinha Tadeu (born in São Paulo)

STILTS

.

The dirty water grabs you

quietly, falsely, and you don’t even scream

You mix your innocence

with crab feces and mud

.

And you sleep precociously

holding your toy.

Gliding over the water

under the stilts.

.

The sun comes and goes

and doesn’t dry you out

in its foamy sheets

You’re one less to share the bread!

. . .

PALAFITAS

.

A água insalubre te recolhe

quieta, falsa, e tu nem gritas.

Misturas tua alvura

com fezes caranguejo e lama.

.

E dormes precocemente

segurando teu brinquedo.

Deslizando sob as águas

debaixo das palafitas.

.

O sol se vem e se vai

e não te enxuga

no lençol de espumas.

És menos um, na partilha do pão!

. . .

Other Black Brazilian poets featured in Cadernos Negros…

https://zocalopoets.com/2014/06/

. . . . .

“The Road Before Us”: Gay Black Poets from a generation ago

Posted: February 23, 2016 Filed under: English, The Road Before Us: Gay Black Poets from a generation ago | Tags: Assotto Saint, Black History Month poems Comments Off on “The Road Before Us”: Gay Black Poets from a generation agoPreface to The Road Before Us: 100 Gay Black Poets (1991)

.

The Road Before Us could have taken a far different path. As its editor and co-publisher, what I wanted foremost was a collection that would provide one more stepping-stone on the road to gay black poetical empowerment. Too often this has been the road not taken.

.

Each poet in this volume is represented by one poem…..

I relish this mixture of styles, which are as wide-ranging as our concerns. The myths, metaphors, and mundaneness of our gay black community, like those of any other community, broaden and deepen everyone’s knowledge of what it is to be human.

.

Most of the poets in this anthology have never appeared in a book before…..

It is my dream that all these fine young writers will keep penning poetry, polishing their craft, and juicing up a literally dying art.

.

The title The Road Before Us is borrowed from a line in the poem “Hejira” that the late Redvers JeanMarie wrote about our friendship. He dedicated it to me. I cherish it. It is anthologized here. The choice of “gay black poets” rather than “black gay poets” was a personal one. I originally used the working subtitle Gay African-American Poets – to which some contributors strongly objected because they were not born in the United States and, moreover, have not chosen to naturalize as American citizens (as I have).

.

Afrocentrists in our community have chosen the term “black gay” to identify themselves. As they insist, black comes first. Interracialists in our community have chosen the term “gay black” to identify themselves. As they insist, gay comes first. Both groups’ self-descriptions are ironically erroneous. It’s not which word comes first that matters, but rather the grammatical context in which those words are used – either as an adjective or as a noun. An adjective is a modifier of a noun. The former is dependent upon the latter.

.

I have never labeled myself either Afrocentrist or interracialist. From reading or seeing my theatre pieces, many might characterize me as an Afrocentrist; but others might immediately characterize me as an interracialist because I have loved and lived with a white man for the past eleven years.

.

Although I make no excuses or apologies for the racially bold statements in my writings, I also owe no one any justification of my “till-death-do-us-part” interracialist relationship. While the black gay vs. gay black debate rages on, in much-needed constructive dialogue, we’d best ponder, as L. Lloyd Jordan did at the conclusion of his essay “Black Gay vs. Gay Black”(BLK, June 1990): “Who are gay blacks and black gays? Halves of a whole. Brothers.”

.

Furthermore, I consider my sexuality a preference. Most of us have an inclination to bisexuality that we don’t acknowledge or act upon. I am very proud of my gayness – which is not to be confused with homosexuality.

.

In the preface to his book Gay Spirit, Mark Thompson explains this distinction clearly: “Gay implies a social identity and consciousness actively chosen, while homosexual refers to a specific form of sexuality. A person may be homosexual, but that does not necessarily imply that he or she would be gay.”

I declare that a person may be gay – but not necessarily homosexual.

.

Colour – and it is much more than skin pigmentation – is not a preference. The same has not to this day been scientifically demonstrated regarding our gayness, which is so much more than sexual orientation. It’s hard to imagine that any writer in this anthology would ever want to change either his colour or his gayness, given a choice.

.

I realize that these views add fuel to the “fire and brimstone” pronouncements of those in far-right politics who argue that we lesbians and gays could change to “normal” if we wanted to.

.