Andre Bagoo: “I am the Archipelago”: Eric Roach and Black Identity

Posted: February 28, 2015 Filed under: 7 GUEST EDITORS, Andre Bagoo, English, Eric Merton Roach | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Andre Bagoo: “I am the Archipelago”: Eric Roach and Black Identity“I am the Archipelago”: Eric Roach and Black Identity

By Andre Bagoo

.

THOSE who know Eric Roach, know how the story ends. This year marks the centenary of the Trinidadian poet who was born in 1915 at Mount Pleasant, Tobago. He worked as a schoolteacher, civil servant and journalist, among other things. Along the way, he published in periodicals regularly. But in 1974, he wrote the poem ‘Finis’, drank insecticide, then swam out to sea at Quinam Bay. The first-ever collected edition of his poetry only appeared two decades after his death. In it, Ian McDonald describes Roach as, “one of the major West Indian poets”. He places Roach alongside Claude McKay, Derek Walcott, Louise Bennett, Martin Carter and Edward Kamau Brathwaite.

.

Too often is the discourse on Roach coloured by his story’s ending. We cannot ignore the facts of what occurred at Quinam Bay, yes, but sometimes they distract from the poet’s genuine achievements. Notwithstanding the emerging consensus on his stature, he is still best known for his ill-fated death. Yet the journey is sometimes more important than the destination.

.

In an introduction to the same collected edition of Roach’s poems published by Peepal Tree Press in 1992, critic Kenneth Ramchand states: “in the English-speaking Caribbean, is there anyone who had written as passionately about slavery and its devastations before ‘I am the Archipelago’ (1957) hit our colonised eardrums?” Ramchand notes that Roach was, “committed, as selflessly and as passionately as one can be, to the idea of a unique Caribbean civilisation taking shape out of the implosion of cultures and peoples in the region.” For Ramchand, “the ultimate justification of [Roach’s] art would be that it contributed to the making and understanding of this new, cross-cultural civilisation.” That cross-cultural civilisation is the one Walcott speaks of when he remarks:

.

Break a vase, and the love which reassembles the fragments is stronger than the love which took its symmetry for granted when it was whole….This gathering of broken pieces is the care and pain of the Antilles….Antillean art is this restoration of our shattered histories, our shards of vocabulary, our archipelago becoming a synonym for pieces broken off from the original continent.

.

This is really a call for the new breed of Caribbean poets, the breed that reverses colonialisation’s history of plunder. Just as our colonial overlords of the past have done, poets, now, are free to pillage from whichever continent they choose. This is not a process of retribution, but rather the restoration of the resilience of the human spirit itself amid the sea of history. It also asserts the reality of the fact that we are as much a part of world culture as anyone else and cannot be marginalised from it.

.

Roach – sometimes called the “Black Yeats”– was one in a long line of poets for whom imitation and allusion are, in fact, blatant acts of rebellion. He also saw himself as key to the process of forming a West Indian Federation, a political union which he felt required a new poetry. Though that union never came to pass, Roach’s work still serves to engage key aspects of Caribbean identity.

The narrative of Black identity, whatever that may be, has to some extent played on the idea of separate black and white races. It has also called for a rejection of “white” ideas and a return to African ideas. But these are uneasy dichotomies which paper over the realities of history over time, the mixing of races and the idea that race itself is an invention. At the same time, these categories ignore the complexity of colonisation. That process of colonisation saw states and peoples being exploited for economic resources and then, in the mid-20th century, abandoned by colonial motherlands under the pretence of liberation – even as strong economic subservience remains in place to this very day.

.

And this is why Roach remains relevant: he not only asserts that the English language is as much ours as theirs, but also sings of the true implications of history, a history sometimes obscured by neat narratives of “independence” and “emancipation”. This is why Roach is still alive.

. . .

I AM THE ARCHIPELAGO

.

I am the archipelago hope

Would mould into dominion; each hot green island

Buffeted, broken by the press of tides

And all the tales come mocking me

Out of the slave plantations where I grubbed

Yam and cane; where heat and hate sprawled down

Among the cane – my sister sired without

Love or law. In that gross bed was bred

The third estate of colour. And now

My language, history and my names are dead

And buried with my tribal soul. And now

I drown in the groundswell of poverty

No love will quell. I am the shanty town,

Banana, sugarcane and cotton man;

Economies are soldered with my sweat

Here, everywhere; in hate’s dominion;

In Congo, Kenya, in free, unfree America.

.

I herd in my divided skin

Under a monomaniac sullen sun

Disnomia deep in artery and marrow.

I burn the tropic texture from my hair;

Marry the mongrel woman or the white;

Let my black spinster sisters tend the church,

Earn meagre wages, mate illegally,

Breed secret bastards, murder them in womb;

Their fate is written in unwritten law,

The vogue of colour hardened into custom

In the tradition of the slave plantation.

The cock, the totem of his craft, his luck,

The obeahman infects me to my heart

Although I wear my Jesus on my breast

And burn a holy candle for my saint.

I am a shaker and a shouter and a myal man;

My voodoo passion swings sweet chariots low.

.

My manhood died on the imperial wheels

That bound and ground too many generations;

From pain and terror and ignominy

I cower in the island of my skin,

The hot unhappy jungle of my spirit

Broken by my haunting foe my fear,

The jackal after centuries of subjection.

But now the intellect must outrun time

Out of my lost, through all man’s future years,

Challenging Atalanta for my life,

To die or live a man in history,

My totem also on the human earth.

O drummers, fall to silence in my blood

You thrum against the moon; break up the rhetoric

Of these poems I must speak. O seas,

O Trades, drive wrath from destinations.

.

(1957)

. . .

Andre Bagoo is a Trinidadian poet and journalist, born in 1983. His second book of poems, BURN, is published by Shearsman Books. To read more ZP features by Andre Bagoo, click on his name under “Guest Editors” in the right-hand column.

. . . . .

Jackie Ormes: Torchy, Candy, Patty-Jo & Ginger!

Posted: February 28, 2015 Filed under: English | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Jackie Ormes: Torchy, Candy, Patty-Jo & Ginger!

Jackie Ormes (1911-1985), considered to be the first Black-American Woman cartoonist /syndicated comic-strip writer/illustrator, was born Zelda Mavin Jackson in Monongahela, Pennysylvania, just outside of Pittsburgh. She began her newspaper career as a proofreader for the Pittsburgh Courier, an African-American weekly that appeared every Saturday. .

Nancy Goldstein, author of an exceptionally-detailed 2008 biography of Ormes, states:

“In the United States at mid (20th) century – a time of few opportunities for women in general and even fewer for African-American women – Jackie Ormes blazed a trail as a popular cartoonist with the major Black newspapers of the day.” Her cartoon characters Torchy Brown (1937-38, 1950-54), Candy (1945), and the memorable duo of Patty-Jo and Ginger (Ginger a glamorous quasi-“pin-up” girl, and Patty-Jo her frank and accurate kid sister, 1945-56) delighted readers of the Pittsburgh Courier and the Chicago Defender.

“Torchy Brown in Dixie to Harlem” was a comic-strip telling the tale of a Mississippi teenager who finds fame and fortune as a singer and dancer at The Cotton Club. “Candy”, a single-panel comic, featured a wise-cracking housemaid. In the 11-year-running “Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger”, precocious child Patty-Jo “kept it real” (as only a child could) in her commentaries about a range of topics – racial segregation, U.S. Foreign policy, education reform, the atom bomb, McCarthy’s “Red” paranoia, etc., while her older “Sis”, Ginger, posed or strutted in mute mannequin glamour. Both Ginger, and the later Torchy Brown (of Torchy Brown in “Heartbeats”) presented gorgeous and fashionable Black women in an era when few such images were to be found. The final newspaper strip for “Heartbeats” in 1954 also hit home on themes of racism and environmental pollution.

Briefly, from 1947-1949, Ormes was contracted by a doll company to design a realistic Black girl doll (not a Mammy or Topsy stereotype), and she would become an avid doll collector in later life. Married happily for four and a half decades, she retired from cartooning in 1956 but continued to draw and paint still-lifes, portraits and murals. One of the founding directors of the DuSable Museum of African-American History in Chicago, she was deeply committed to her community.

But it is Jackie Ormes’ special populist-art contribution to American culture – her unique comics – that we remember today – during Black History Month 2015!

Ian Williams: “No hay un sinónimo para TI”

Posted: February 27, 2015 Filed under: Ian Williams, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Ian Williams: “No hay un sinónimo para TI”Ian Williams (nacido 1979)

Encuentros informales:

“Soy Sincero – y Tú? Hombre para Mujer – con Foto”

.

Mi ex devolvió a su ex,

entonces busco alguien – otra nueva persona,

alguna lista par diversión adulta, algo directo (según mi parecer):

ni cosas pervertidas, ni llaves en boles; ni cuero, ni juegos de actuación con “palabras cautelosas”.

No quiero palabrerío emocional, y aunque no eres mi “novia”, también no tienes que ser una zorra.

.

Echa un vistazo a mi foto abajo (pregúntame si querías un foto del rostro).

A mi no importa como pareces – soy serio; solo sé sincera.

Quiero buscar una mujer que:

no es autómata del correo-basura,

no es un precio,

no es un virus,

que no es mi ex,

no está hecha de silicona,

y que no es la tipa que eche un polvete con hombres al azar

– pero ella se da cuenta de quedar aquí en esta línea – leyendo, sí, aún leyendo…

. . .

Ecolalia *

.

Una vez que a uno le gana lo que quiere, pues a uno ya no más lo desea…

.

¿A uno ya no más lo desea a cual cosa?

A uno ya no más desea lo que deseaba.

.

Un hombre y una mujer quiere a una mujer y a un hombre

o

a un hombre y a una mujer

(dependiendo del hombre y de la mujer).

.

Una vez que a uno le gana lo que quiere – una vez,

pues a uno ya no más lo quiere solamente una vez,

y pues: a uno ya no más lo quiere – como mucho.

.

Sí pues no. ¿Sí y no? No.

Sí pues no pues sí – y siempre, después de sí

vendrá no. Nunca siempre es sí – pero siempre: no.

Conoce – siempre conoce – que:

después de sí vendrá no.

.

Deseamos lo que deseamos,

no lo que deseabamos…

. . .

* Ecolalia:

Ecolalia (en medecina) es una perturbación del lenguaje en la que el sujeto repite involuntariamente una palabra o frase que acaba de pronunciar otra persona en su presencia, a modo de eco. Es un trastorno del lenguaje caracterizado por la repetición semiautomática, compulsiva e iterativa de las palabras o frases emitidas por el interlocutor e imitando su entonación original.

. . .

La razón que nunca avancé más allá de la primera línea…

Y ahora tú me dices que lo sientes para decir —–

[una primera línea fracasada]

.

1.

Y bien, yo diría lo que dijo mi ex,

si no estuvo alfombrado

hace tiempo…durante los años 90.

1.

Perdoné a ella, a ti, a ella.

1.

¿Cuándo se volvió tú el pronombre correcto para ella?

No tengo nada decirte.

1.

Y tú – a mi. Y ella – a mi.

1.

Nada decir a ella.

Sigo trenzándonos en cuadriculados.

1.

No lloré durante la noche,

y no lloré ningún río a causa de ti. Ella.

¿A quién bromeamos, eh? Tú.

. . .

Los tres poemas arriba: del poemario Anuncios personales © 2012 Ian Williams

. . .

Excepto Tú

.

No diga:

No decimos cosas como __________ por aquí.

.

Aun con el mudo selectivo de estados cuadrados, zonas horarias,

y el tiempo entre nosotros, todavía no ro hacemos.

Nos ladeamos el teléfono a otra parte de la oreja,

llenamos la boca con esponja:

Que la pases bien esta noche

o

Muy bien, hasta otra…

pues colgamos el teléfono

por si acaso uno de nosotros no lo dice – o lo dice.

Un tarareo en la garganta, un trino, o nos aclaramos la voz

– Te amo

y

No lo digas.

.

Una vez mi abuela casi lo dijo…

Yo vi su cuello, y sus manos – trinando.

Mi abuelo había regresado de las colinas de Speyside,

durante el mediodía, llevando su sombrero, y ella le dijo:

Estoy contenta que has vuelto, seguro

– dicho formalmente,

como estuvo limpiando las palmas sobre los pliegues de su vestido.

.

Cuando el se murió,

los aldeanos tenían miedo que ella vagabundeara en las colinas

con el machete herrumbroso de su difunto,

y con faisanes atados en su vieja cintura,

dándole voces en un falsete agudo.

Nunca deambuló. O le descubrieron antes.

Ella nunca llamaba a él nada

sino Tú.

. . .

Terceto para TÚ

.

Hay un sinónimo para ti.

Y mil millones de nombres para los hombres como mi,

ningún para ti. Ningunos. Muy pocos.

No hay un sinónimo para TI.

Dice el tesauro: no hay una pareja. ¿Quieres decir “yogi”?

¿Puede qué use ti?

Ah no – hay ningún sinónimo para tú,

y mil millones de nombres para los hombres como yo.

. . .

Excepto Tú y Terceto para T\P

del poemario Conoces Quien Eres (You Know Who You Are) © Ian Williams 2010

. . .

Ian Williams, escritor y poeta, nació en 1979. Ganó su doctorado en Inglés de la Universidad de Toronto, y ahora (2014-2015) está enseñando a los estudiantes de la Universidad de Calgary en Alberta, Canadá. La Corporación Canadiense de Radiodifusión (CBC) le mencionó como “uno de los diez nuevos escritores canadienses prometedores”…

. . . . .

Kendel Hippolyte: Blues Rizado y Blues Cuerdo

Posted: February 27, 2015 Filed under: English, Kendel Hippolyte, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Kendel Hippolyte: Blues Rizado y Blues Cuerdo

Kendel Hippolyte (poeta de Santa Lucía, Caribe, nacido 1952)

Blues Rizado*

.

en la ciudad aquí afuera, me estoy ahogando en mi rarezas,

de un esfuerzo por quedarme auténtico…

la cabeza flotante, el cuerpo hundiendo,

mi cabeza va navegando pero estoy sumergiendo…

.

las mujeres venden ciruelas, los hombres venden barras de chocolate…

compra uno – o el otro – quizás los dos

pero cuídate con el comprando, porque algunos se pudren ya

– es valuable el dinero, y la putrfacción propaga tan fácilmente…

.

hacia arriba de los caminos cruzados, intercambio mi rostro

pero no hay nadie que lo compre – ¿y quién necesita un rostro?

me embolso mi cara y me maquillo con una inexpresiva,

muy tarde para las caras, y me pongo la vacía…

.

anoche, estaba oscuro como alquitrán, los faros se fundieron,

y ahora, por fin, conozco adonde voy…

estoy buscando a Kinky (“Rizado”) – ha cambiado su dirección, es el mismo lugar pero ha cambiado su dirección

.

vivo por el resto de mi miedo y estoy muriendo en mi “vivo”,

tengo que aprender como cantar desafinado,

me siento extraño, al primero, pero me sentiré de acuerdo, muy pronto,

tan pronto como puedo aprender esta canción, voy a sentirme bien.

. . .

* Rizado tiene aquí el sentido de pelo rizado o de la mente excéntrica/estrafalária. También es simplemente un apodo encantador.

. . .

Kendel Hippolyte

Kinky Blues

.

in the city out here, i’m drowning in my weird

from trying to stay real

head floating, body going under

head sailing, but i’m going under

.

the women sell plums, the men sell chocolate bars

buy one or the other or both

but watch your buying, some are rotten already

money is precious and rot spreads too easy

.

up at the crossroads, i’m selling my face

but no one’s buying – who needs a face

i pocket my face, put on a blank

too late for faces, i put on a blank

.

last night dark as asphalt, my headlight blew out

now i finally know where i’m going

looking for kinky, he’s changed his address

still the same place, but he’s changed his address

.

living out my afraid, i’m dying in my alive

i must learn to sing out of key

feels strange at first, but i’ll soon be alright

soon’s i learn this song, i’ll be alright.

. . .

Blues Cuerdo

.

Ah, he intentado ser cuerdo, sí, tan largo tiempo,

pues ahora estoy intentando a ver el beneficio

– me pregunto, me pregunto

.

Desde muchos años me he quedado quieto, agarrando,

y yo había debido pensado que: es lo correcto hacer

– ya no más, ya no más

.

Porque estoy perdiendo motivos para constreñir mi alma,

quizás debo ponerla en libertad, dejarme entregarme

por esta hambre (qué hambre)

.

¿Y supón que yo permito quedar libre el mismo, mi naturaleza?

¿Se desbocaría hacia una biblia? ¿una mujer? ¿un lazo de horca?

– me pregunto, me pregunto

.

¿Cielo azul? ¿Nube negra? ¿Triunfar o fracasar?

¿Cómo lo sabré? ¿Y cómo yo escogiere?

Oigo un trueno.

. . .

Del poemario Visión por la noche (Night Vision), lanzado por TriQuarterly Books © 2005 Kendel Hippolyte

. . .

Sane Blues

.

Oh i’ve tried for so long to be sane

And now i’m trying to see my gain

i wonder

i wonder

.

For years i’ve kept myself held tight

I must have thought that this was right

No longer

No longer

.

‘Cause i’m losing the reasons for holding it in

Perhaps i should let go, let my self give in

to this hunger

this hunger

.

Suppose i let that self run loose?

Would it run to a bible? A woman? A noose?

i wonder

i wonder

.

Blue sky? Black cloud? Win or lose?

How can i know? How do i choose?

.

i hear thunder.

. . .

From: Night Vision (TriQuarterly Books) © 2005 Kendel Hippolyte

. . . . .

Kendel Hippolyte: Snow as metaphor…

Posted: February 27, 2015 Filed under: English, Kendel Hippolyte Comments Off on Kendel Hippolyte: Snow as metaphor…Kendel Hippolyte

Snow

.

It’s snowing in our land.

The warmth evaporates, the cold settles

on hill and house, on friends we knew, on families.

A fallout from a cold war covers them

and they diminish, disappear into a blizzard.

Snow falls, a blitz of words.

News crackles in the air like frostbite,

a bland subtle obliteration hiding from us

the common ground.

.

Till even flesh and blood numb into snowmen,

caricatures formed with the precipitate from TV screens.

The flakes, the white lies, drift, bury the mindscape,

and we shape our effigies

– honkies, terrorists, reactionaries –

then smash them.

.

Snow in the tropics.

Lately we pass each other in a gorge,

fearful between its east and west walls.

We do not call out, we whisper, we dare not declare

that despite this, despite the chillblain hardening over our hearts,

we still are

what we have always been:

Man-Woman, looking for fruitful ground again.

.

We walk, the flakes fall, wintering the mind,

blurring a dimming memory of garden, shared fruit in warm air.

And we know

by our cold silence, our static fear,

trudging through drift and blur, hoping we’ll find our homes again,

we are becoming snow.

. . .

Kendel Hippolyte was born in Castries, Saint Lucia, in 1952. He has written a half dozen books of poetry, most recently Fault Lines, published by Peepal Tree Press in 2012. Fault Lines was awarded the OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature in 2013. Hippolyte has twice won the Minvielle and Chastanet Fine Arts Award for Literature, the premier arts award in Saint Lucia, and was awarded the St. Lucia Medal of Merit for his contribution to the arts. He has taught at St.Mary’s College in Vigie, and Sir Arthur Lewis College at the Morne. He co-founded the Lighthouse Theatre Company, where he is actively involved as both a playwright and director. Mr. Hippolyte is married to fellow St-Lucian poet and teacher Jane King.

. . .

Winter-cold and snow in the poems of Claude McKay:

https://zocalopoets.com/2012/02/08/claude-mckay-the-tropics-in-new-york/

. . . . .

Tanya Shirley, poeta jamaicana: dos poemas “confidenciales”

Posted: February 26, 2015 Filed under: English, Spanish, Tanya Shirley, ZP Translator: Alexander Best Comments Off on Tanya Shirley, poeta jamaicana: dos poemas “confidenciales”Tanya Shirley (poeta jamaicana)

Cáncer (parte 1)

.

Es algo duro, mirar el hedor en su cara

cuando sabemos que él no pertenece

en la caverna de una mujer que crió rosas

y que trajo un árbol de mango todo el camino hasta aquí – de Jamaica –

por los vecinos que no podían permitirles viajar.

.

Luna, trozo de la luna, hija de Señorita Iris (chismosa de la aldea)

y de Señor Zackariah (el granjero),

deberías haber decir No al hombre de piel demasiado morena

que te pidió la mano en Infierno y Matrimonio.

Pero no podemos culpar a él este residuo de lágrimas enrolladas

que se tumba – tumoroso – sobre tu páncreas.

De veras: Le amabas, también amabas a sus otros niños, de “afuera”…

.

Mientras desenrollamos la sábana manchada, tirándola de ti,

Sonríes; pasas tus dedos hacia el pelo gris “ahi abajo”,

y tuerces las mechas como cuentos para antes de dormir que te arropas.

Te levantamos, te extendemos, te limpiamos, te empolvamos.

Ahora, en tu limpio, nuevo pañal, empiezas a roncar…

. . .

Tanya Shirley (born 1976, Jamaica)

Cancer (Part 1)

.

It is hard staring stench in the face

when you know he doesn’t belong

in the cavern of a woman who reared roses

and brought a mango tree all the way from Jamaica

for the neighbours who couldn’t afford to travel.

.

Luna, slice of the moon, daughter of Miss Iris

the village gossip and Mass Zackariah the farmer,

you should have said ‘no’ to the blue-black man

who asked your hand in hell and marriage.

But we cannot blame him for this residue of balled-up tears

lying tumorous on your pancreas;

you loved him and his outside children.

.

As we roll the stained sheet from under you,

you smile, slide your fingers to the grey hairs down there,

twirl strands like stories tucking you in.

We lift and spread, wipe and powder.

In clean, new diapers, you snore off.

. . .

Tanya Shirley

Mi amiga cristiana

.

Ella me dice que renunciará el acto de sexo – haciendo el amor – por la Cuaresma.

Porque: después de lo que sufrió nuestro Salvador, bien – es, por lo menos, algo ella puede hacer para probar su fe.

.

Entonces, está rezando que tenga la fortaleza de ánimo para guardar asegurado – encerrado – sus piernas; y ésto solo es su motivo de rezar.

.

Pensaba que cuarenta días, ay, que largo tiempo sería,

pues me dijo que Dios entenderá – fijo – si ella solo puede ser férrea durante un mes (no más).

.

Entiende que el sexo antes del matrimonio es inmoral,

y yo le pregunté: ¿Qué pasará al fin de ese mes?

Yo, cuando me he puesto a régimen una semana, pues en los días que siguen tengo que comer todo el alimento que encuentro en frente de mí – ¡todo lo que pueda “integrar” dentro de mi boca!

.

(Santo cielo, Dios quiera que ella no abre sus piernas como yo abro mi boca…)

.

Me dijo que lo que importa es el único mes de sacrificio

que será escrito en El Gran Libro…

Y si todo va según su plan,

el pecado será anulado

a causa de su sacrificio durando ese mes.

.

Le digo:

¡Qué agradable es, que hay tanta flexibilidad en el cristianismo!

y también, que La Biblia es el buenísimo libro de poesía.

.

Lo odia el hecho de mi sarcasmo,

pero a la larga sentiré mucho orgullo en ella

– si su hombre bonbón no decide vestir su camisa roja…

.

La mera idea de él

– llevando su camisa roja –

obliga a mi amiga murmurar una oración mientras charlamos…

. . .

My Christian Friend

.

She says she’s going to give up sex for Lent,

because after what the Saviour went through,

it’s the very least she can do to prove her faith.

.

So now she’s praying for the strength

to keep her legs locked – and that’s all

she’s been praying for.

.

She thought forty days was too long

so she said God will understand

if she’s only strong for a month.

.

She knows sex before marriage is wrong,

so I ask her what will happen after the month.

After I’ve been on a diet for a week,

the following week I eat everything I find

that fits into my mouth.

.

God forbid if she opens her legs

the way I open my mouth.

.

She says it’s the one month sacrifice

that will be written down in the big book,

so if all this works according to her plan

then the sin itself will be cancelled out

by the one month sacrifice.

.

I tell her isn’t it nice that there’s flexibility

in Christianity, and the Bible is really just

a good book of poetry.

.

She says she hates when I’m sarcastic,

and I’ll be really proud of her in the end,

that is, she says, if her oh so sexy man

doesn’t wear his red shirt.

.

Just the thought of him in his red shirt

has her mumbling a prayer while we speak.

. . .

Tanya Shirley, nacida en 1976, es profesora de literaturas ingleses en la Universidad del Caribe (University of the West Indies), situada en Mona, Jamaica. Su primer poemario, Ella que duerme con huesos (She Who Sleeps With Bones) fue publicado en 2009, y su último, titulado El detallista de plumas (The Merchant of Feathers), fue lanzado este enero pasado (2015).

. . .

Tanya Shirley teaches Literatures in English at the University of the West Indies, Mona campus. She earned an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Maryland, USA. Her work has appeared in Small Axe and The Caribbean Writer, and she received an International Publication Prize from Atlanta Review in 2005. She is a Cave Canem Fellow and a past participant in Callaloo Creative Writing Workshops. Her debut collection, She Who Sleeps With Bones, was published in 2009, and The Merchant of Feathers has just come out (January 2015).

. . . . .

Esther Phillips: “How does the heart recover from the lives we’ve met and touched?”

Posted: February 25, 2015 Filed under: English, Esther Phillips Comments Off on Esther Phillips: “How does the heart recover from the lives we’ve met and touched?”Esther Phillips (Barbados, born 1950)

My Brother

.

A little boy ran down

the road with a roller,

his magic metal wand

striking mirrored

memories of you,

my brother.

.

How often did your

bare feet hammer

your frustration into

this hot tar, insistent

hands striking, every

lash echoing your own pain,

willing with furrowed brow

and glinting tears the roller

to go straight, for so might

your own stifled dreams

one day run straight and true?

.

What gadgets do you play with now,

brother?

Time machines? Computers?

Do you drive your high-

powered car with surer aim

down paved highways,

your eyes glinting blood and steel

so that I hardly know you?

.

For a moment now you’re pushing

your roller back down the road.

But as it swerves off-course,

I rescue it for you

I right it for you

I hand it back to you

and you smile at me.

. . .

Unwritten Poem

.

You never gave me time

to write your poem.

I needed time to know you:

the fledgling husband playing

his unaccustomed role,

no model given from the past;

.

your hip-hop scene, what lines

or rhythms hooked your soul

until you felt all that was earth

and heaven pulsed within this music;

what zeal, what rebel songs

ignited you, your manhood,

your secret passions into being.

.

When should I have written your poem?

The day of your wedding?

when you, handsome in tuxedo,

took her hand and swore

that you would love her always?

.

Would it have been the day

you placed my grandchild in my arms?

For in that very moment, my heart

would have soared upwards.

.

Or when we strolled the summer

morning in the woods, and laughed

at makeshift walking sticks,

cleared a few vines, picked

some wildflowers for my daughter,

talked of dirt-bikes, old relics,

nothing in particular;

just glad a woman and her son-in-law

could have no discord.

.

Should it have been the night

I stood behind your sleeping form

and prayed with all the fervour of my heart,

my right hand stretched towards you?

And deep in your unconscious sleep,

you stretched your right hand out

.

and held it still, suspended, under mine.

I did not speak for fear of waking you,

nor could you see me in the darkness

where I stood. I never will forget

the strange, transcendent moment.

.

But now you’re gone,

and all the hopes I cherished, prized,

will flourish in the gaze of someone else’s eyes.

How does the heart recover from the lives

we’ve met and touched? So little time,

so little time, yet loved so much.

. . .

From: The Stone Gatherer, published by Peepal Tree Press © Esther Phillips 2009

. . . . .

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Imaginary Portraits

Posted: February 23, 2015 Filed under: IMAGES Comments Off on Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Imaginary Portraits“Painting for me is the subject. The figures exist only through paint, through colour, line, tone and mark-making…..They don’t share our concerns or anxieties. They are somewhere else altogether.”

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye was born in London, England, in 1977; her parents had immigrated from Ghana. Her paintings, which appear to be single or group portraits, are, in fact, made up of fictitious characters: composites from her imagination, people who don’t really exist.

Yiadom-Boakye studied at Central Saint Martin’s School of Art (1996-97), Falmouth College of Art (1997-2000), and the Royal Academy Schools (2000-2003). She has exhibited widely – in London, New York City/Harlem, Lyons and Frankfurt.

. . .

Teju Cole on photographer Roy DeCarava: A True Picture of Black Skin

Posted: February 23, 2015 Filed under: English | Tags: Black History Month Comments Off on Teju Cole on photographer Roy DeCarava: A True Picture of Black SkinTeju Cole on photographer Roy DeCarava: A True Picture of Black Skin

(reprinted from The New York Times Magazine, February 18th, 2015)

.

What comes to mind when we think of photography and the civil rights movement? Direct, viscerally affecting images with familiar subjects: huge rallies, impassioned speakers, people carrying placards (“I Am a Man”), dogs and fire hoses turned on innocent protesters. These photos, as well as the portraits of national leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, are explicit about the subject at hand. They tell us what is happening and make a case for why things must change. Our present moment – 2015 – a time of vigorous demand for equal treatment, evokes those years of sadness and hope in Black American life and renews the relevance of those photos.

But there are other, less expected images from the civil rights years that are also worth thinking about: images that are forceful but less illustrative.

One such image left me short of breath the first time I saw it.

It’s of a young woman whose face is at once relaxed and intense. She is apparently in bright sunshine, but both her face and the rest of the picture give off a feeling of modulated darkness; we can see her beautiful features, but they are underlit somehow. Only later did I learn the picture’s title, “Mississippi Freedom Marcher, Washington, D.C., 1963” which helps explain the young woman’s serene and resolute expression. It is an expression suitable for the event she’s attending, the most famous civil rights march of them all. The title also confirms the sense that she’s standing in a great crowd, even though we see only half of one other person’s face (a boy’s, indistinct in the foreground) and, behind the young woman, the barest suggestion of two other bodies.

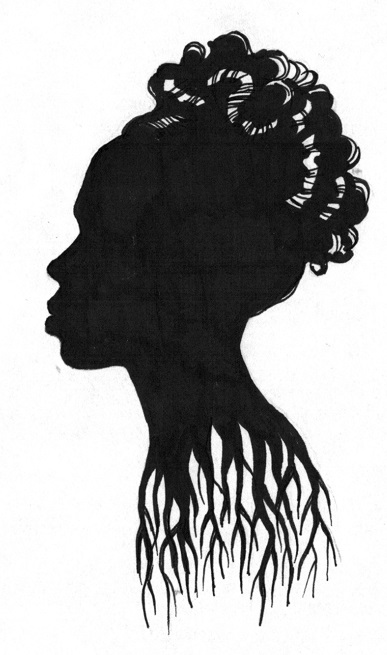

The picture was taken by Roy DeCarava (1919-2009), one of the most intriguing and poetic of American photographers. The power of this picture is in the loveliness of its dark areas. His work was, in fact, an exploration of just how much could be seen in the shadowed parts of a photograph, or how much could be imagined into those shadows. He resisted being too explicit in his work, a reticence that expresses itself in his choice of subjects as well as in the way he presented them.

.

DeCarava, a lifelong New Yorker, came of age in the generation after the Harlem Renaissance and took part in a flowering in the visual arts that followed that largely literary movement. By the time he died in 2009, at 89, he was celebrated for his melancholy and understated scenes, most of which were shot in New York City: streets, subways, jazz clubs, the interiors of houses, the people who lived in them. His pictures all share a visual grammar of decorous mystery: a woman in a bridal gown in the empty valley of a lot, a pair of silhouetted dancers reading each other’s bodies in a cavernous hall, a solitary hand and its cuff-linked wrist emerging from the midday gloom of a taxi window. DeCarava took photographs of white people tenderly but seldom. Black life was his greater love and steadier commitment. With his camera he tried to think through the peculiar challenge of shooting black subjects at a time when black appearance, in both senses (the way black people looked and the very presence of black people), was under question.

.

All technology arises out of specific social circumstances. In our time, as in previous generations, cameras and the mechanical tools of photography have rarely made it easy to photograph black skin. The dynamic range of film emulsions, for example, were generally calibrated for white skin and had limited sensitivity to brown, red or yellow skin tones. Light meters had similar limitations, with a tendency to underexpose dark skin. And for many years, beginning in the mid-1940s, the smaller film-developing units manufactured by Kodak came with Shirley cards, so-named after the white model who was featured on them and whose whiteness was marked on the cards as “normal.” Some of these instruments improved with time. In the age of digital photography, for instance, Shirley cards are hardly used anymore. But even now, there are reminders that photographic technology is neither value-free nor ethnically neutral. In 2009, the face-recognition technology on HP webcams had difficulty recognizing black faces, suggesting, again, that the process of calibration had favored lighter skin.

An artist tries to elicit from unfriendly tools the best they can manage. A black photographer of black skin can adjust his or her light meters; or make the necessary exposure compensations while shooting; or correct the image at the printing stage. These small adjustments would have been necessary for most photographers who worked with black subjects, from James Van Der Zee at the beginning of the century to DeCarava’s best-known contemporary, Gordon Parks, who was on the staff of Life magazine. Parks’s work, like DeCarava’s, was concerned with human dignity, specifically as it was expressed in black communities. Unlike DeCarava, and like most other photographers, he aimed for and achieved a certain clarity and technical finish in his photo essays. The highlights were high, the shadows were dark, the mid-tones well-judged. This was work without exaggeration; perhaps for this reason it sometimes lacked a smoldering fire even though it was never less than soulful.

DeCarava, on the other hand, insisted on finding a way into the inner life of his scenes. He worked without assistants and did his own developing, and almost all his work bore the mark of his idiosyncrasies. The chiaroscuro effects came from technical choices: a combination of underexposure, darkroom virtuosity and occasionally printing on soft paper. And yet there’s also a sense that he gave the pictures what they wanted, instead of imposing an agenda on them. In “Mississippi Freedom Marcher,” for example, even the whites of the shirts have been pulled down, into a range of soft, dreamy grays, so that the tonalities of the photograph agree with the young woman’s strong, quiet expression. This exploration of the possibilities of dark gray would be interesting in any photographer, but DeCarava did it time and again specifically as a photographer of black skin. Instead of trying to brighten blackness, he went against expectation and darkened it further. What is dark is neither blank nor empty. It is in fact full of wise light which, with patient seeing, can open out into glories.

This confidence in “playing in the dark” (to borrow a phrase of Toni Morrison’s) intensified the emotional content of DeCarava’s pictures. The viewer’s eye might at first protest, seeking more conventional contrasts, wanting more obvious lighting. But, gradually, there comes an acceptance of the photograph and its subtle implications: that there’s more there than we might think at first glance, but also that when we are looking at others, we might come to the understanding that they don’t have to give themselves up to us. They are allowed to stay in the shadows if they wish.

.

Thinking about DeCarava’s work in this way reminds me of the philosopher Édouard Glissant, who was born in Martinique, educated at the Sorbonne and profoundly involved in anticolonial movements of the ’50s and ’60s. One of Glissant’s main projects was an exploration of the word “opacity.” Glissant defined it as a right to not have to be understood on others’ terms, a right to be misunderstood if need be. The argument was rooted in linguistic considerations: It was a stance against certain expectations of transparency embedded in the French language. Glissant sought to defend the opacity, obscurity and inscrutability of Caribbean blacks and other marginalized peoples. External pressures insisted on everything being illuminated, simplified and explained. Glissant’s response: No. And this gentle refusal, this suggestion that there is another way, a deeper way, holds true for DeCarava, too.

DeCarava’s thoughtfulness and grace influenced a whole generation of black photographers, though few of them went on to work as consistently in the shadows as he did. But when I see luxuriantly crepuscular images like Eli Reed’s photograph of the Boys’ Choir of Tallahassee (2004), or those in Carrie Mae Weems’s “Kitchen Table Series” (1990), I see them as extensions of the DeCarava line. One of the most gifted cinematographers currently at work, Bradford Young, seems to have inherited DeCarava’s approach even more directly. Young shot Dee Rees’s “Pariah” (2011) and Andrew Dosunmu’s “Restless City” (2012) and “Mother of George” (2013), as well as Ava DuVernay’s “Selma” (2014). He works in color, and with moving rather than still images, but his visual language is cognate with DeCarava’s: Both are keeping faith with the power of shadows.

The leading actors in the films Young has shot are not only black but also tend to be dark-skinned: Danai Gurira as Adenike in “Mother of George,” for instance, and David Oyelowo as Martin Luther King Jr., in “Selma.” Under Young’s lenses, they become darker yet and serve as the brooding centers of these overwhelmingly beautiful films. Black skin, full of unexpected gradations of blue, purple or ocher, set a tone for the narrative: Adenike lost in thought on her wedding day, King on an evening telephone call to his wife or in discussion in a jail cell with other civil rights leaders. In a larger culture that tends to value black people for their abilities to jump, dance or otherwise entertain, these moments of inwardness open up a different space of encounter.

These images pose a challenge to another bias in mainstream culture: that to make something darker is to make it more dubious. There have been instances when a black face was darkened on the cover of a magazine or in a political ad to cast a literal pall of suspicion over it, just as there have been times when a black face was lightened after a photo shoot with the apparent goal of making it more appealing. What could a response to this form of contempt look like? One answer is in Young’s films, in which an intensified darkness makes the actors seem more private, more self-contained and at the same time more dramatic. In “Selma,” the effect is strengthened by the many scenes in which King and the other protagonists are filmed from behind or turned away from us. We are tuned into the eloquence of shoulders, and we hear what the hint of a profile or the fragment of a silhouette has to say.

I think of another photograph by Roy DeCarava that is similar to “Mississippi Freedom Marcher,” but this other photograph, “Five Men, 1964,” has quite a different mood. We see one man, on the left, who faces forward and takes up almost half the picture plane. His face is sober and tense, his expression that of someone whose mind is elsewhere. Behind him is a man in glasses. This second man’s face is in three-quarter profile and almost wholly visible except for where the first man’s shoulder covers his chin and jawline. Behind these are two others, whose faces are more than half concealed by the men in front of them. And finally there’s a small segment of a head at the bottom right of the photograph. The men’s varying heights could mean they are standing on steps. The heads are close together, and none seem to look in the same direction: The effect is like a sheet of studies made by a Renaissance master. In an interview DeCarava gave in 1990 in the magazine Callaloo, he said of this picture: “This moment occurred during a memorial service for the children killed in a church in Birmingham, Ala., in 1964. The photograph shows men coming out of the service at a church in Harlem.” He went on to say that the “men were coming out of the church with faces so serious and so intense that I responded, and the image was made.”

The adjectives that trail the work of DeCarava and Young as well as the philosophy of Glissant — opaque, dark, shadowed, obscure — are metaphorical when we apply them to language. But in photography, they are literal, and only after they are seen as physical facts do they become metaphorical again, visual stories about the hard-won, worth-keeping reticence of black life itself. These pictures make a case for how indirect images guarantee our sense of the human. It is as if the world, in its careless way, had been saying, “You people are simply too dark,” and these artists, intent on obliterating this absurd way of thinking, had quietly responded, “But you have no idea how dark we yet may be, nor what that darkness may contain.”

. . .

Teju Cole is a Nigerian-American writer whose two works of fiction, Open City and Every Day Is for the Thief, have been critically acclaimed and awarded several prizes, including the PEN/Hemingway Award. He is distinguished writer in residence at Bard College and the NYT magazine’s photography critic. A writer, art historian, and photographer, he was born in the US in 1975 to Nigerian parents, and raised in Nigeria. He currently lives in Brooklyn.

. . .