El Día del Aborigen Americano – en inglés: Michelle Obama / April 19th: The Day of The Indian of The Americas: A speech by Michelle Obama

Posted: April 19, 2015 Filed under: English Comments Off on El Día del Aborigen Americano – en inglés: Michelle Obama / April 19th: The Day of The Indian of The Americas: A speech by Michelle ObamaPrepared Remarks by First Lady Michelle Obama for The White House Convening on Creating Opportunity for Native Youth [edited for length]:

Washington, D.C., U.S.A.

April 8th, 2015

.

Good morning, everyone, and welcome to the White House. We are so thrilled to have you here today for our “Generation Indigenous” convening…

.

And as for T.C…there really are no words to express how proud I am of this young man, and how impressed I am by his courage, determination and maturity. Barack and I were blown away by T.C. and by the other young people we met when we visited T.C.’s tribe, the Standing Rock Sioux Nation, last June. And I want to start off today by telling you a little bit about that visit…

It began when we arrived in North Dakota, and as we left the airport where we’d landed, we looked around, and all we could see was flat, empty land. There were almost no signs of typical community life, no police stations, no community or business centers, no malls, no doctor’s offices, no churches, just flat, empty land.

Eventually, we pulled up to a little community with a cluster of houses, a few buildings, and a tiny school – and that was the town of Cannon Ball, North Dakota, which is part of the Standing Rock Sioux Nation. And at that school a small group of young people gathered in a classroom, anxiously but quietly waiting to meet with the President and the First Lady.

These teens were the best and brightest – hand-selected for this meeting – and after we all introduced ourselves, they shared their stories.

One young woman was in foster care because of substance abuse in her household. She talked about how hard it was to be separated from her five siblings. One young man had spent his high school years homeless, crashing on the sofa of his friends, even for a period living in the local community center. Another young man had gotten himself into college, but when he got there, he had trouble choosing the right classes; he realized that he’d never been taught how to properly write an essay; and when family problems arose back home, he struggled to balance all the stress and eventually had to drop out.

And just about every kid in that room had lost at least one friend or family member to drug or alcohol-related problems, or to preventable illnesses like heart disease, or to suicide. In fact, two of the girls went back and forth for several minutes trying to remember how many students in their freshman class had committed suicide – the number was either four or five…this is out of a class of 70.

Just sit with that for a minute: four or five kids out of a class of 70, taking their own lives.

So these are the challenges these kids are facing. This is the landscape of their lives.

But somehow – and this is what truly blew us away – somehow, in the face of all this hardship and all these tragedies, these kids haven’t given up. They are still fighting to find a way forward, for themselves and for their community.

After losing her classmates to suicide, one young woman started volunteering at a youth program to help other kids who were struggling. One young man told us that when his family was struggling he fended for himself for years, sleeping on friends’ couches until he was old enough to become a firefighter.

And that young man who had to leave college? Well, when he got back home, he discovered that his family problems were worse than he had thought. He found that his stepmother was on drugs and his four younger brothers were wandering the streets alone in the middle of the night. So, at the age of 19, he stepped in and took over – and now, he’s back in college while raising four children all by himself.

And then there’s T.C.

He was the last young person to speak that day, and after telling us his story – how he was raised by a single father, how he’s lost so many people he loves, how his family struggles to get by – he then said to my husband “I know you face a lot as President of the United States, and I want to sing an encouragement song for all of us to keep going.”

After everything these young people had endured, T.C. wanted to sing a song for us.

So if you have any doubt about the urgency or the value of investing in this community, I want you to just think about T.C. and all those other young people I met in Standing Rock, North and South Dakota. I want you to think about both the magnitude of their struggles and the deep reservoirs of strength and resilience that they draw on every day to face those struggles.

And, most of all, I want you to remember that supporting these young people isn’t just a nice thing to do, and it isn’t just a smart investment in their future, it is a solemn obligation that we as a nation have incurred.

You see, we need to be very clear about where the challenges in this community first started…

Folks in Indian Country didn’t just wake up one day with addiction problems. Poverty and violence didn’t just randomly happen to this community. These issues are the result of a long history of systematic discrimination and abuse.

Let me offer just a few examples from our past, starting with how, back in 1830, we passed a law removing Native Americans from their homes and forcibly re-locating them to barren lands out west. The Trail of Tears was part of this process. Then we began separating children from their families and sending them to boarding schools designed to strip them of all traces of their culture, language and history. And then our government started issuing what were known as “Civilization Regulations” – regulations that outlawed Indian religions, ceremonies and practices – so we literally made their culture illegal.

Given this history, we shouldn’t be surprised at the challenges that kids in Indian Country are facing today. And we should never forget that we played a role in this. Make no mistake about it – we own this.

And we can’t just invest a million here and a million there, or come up with some five-year or ten-year plan, and think we’re going to make a real impact. This is truly about nation-building, and it will require fresh thinking and a massive infusion of resources over generations. That’s right, not just years – but generations.

But remember: we are talking about a small group of young people, so while the investment needs to be deep, this challenge is not overwhelming, especially given everything we have to work with. I mean, given what these folks have endured, the fact that their culture has survived at all is nothing short of a miracle.

And, like many of you, I have witnessed the power of that culture…

I saw it at the Pow Wow that my husband and I attended during our visit to Standing Rock. And with each stomping foot – with each song, each dance – I could feel the heartbeat that is still pounding away in Indian Country. And I could feel it in the energy and ambition of those young people who are so hungry for any chance to learn, any chance to broaden their horizons.

We all need to work together to invest deeply – and for the long-term – in these young people, both those who are living in their tribal communities (like T.C.), and those living in urban areas across this country. These kids have so much promise – and we need to ensure that they have every tool, every opportunity they need to fulfill that promise.

I want to thank you for coming here today to learn more about “Generation Indigenous” and how you can help. And I look forward to seeing the extraordinary impact that all of you all will have in the years ahead.

Thank you so much – and God bless.

. . .

http://genindigenous.com/

.

. . . . .

A Sioux Prayer (1887)

(Translation into English: Chief Yellow Lark)

.

Oh Great Spirit, whose voice I hear in the winds,

whose breath gives life to the world,

Hear me!

I come to you as one of your many children;

I am small and weak;

I need your strength and wisdom.

.

May I walk in beauty.

Make my eyes ever behold the red and purple sunset.

Make my hands respect the things you have made,

and that my ears be sharp to your voice.

Make me wise so that I may know the things you have taught your children:

the lessons you have written in every leaf and rock.

.

Make me strong; not to be superior to my brothers, but to fight my greatest enemy: myself.

Make me ever ready to come to you with straight eyes,

So that when life fades as the fading sunset,

May my spirit come to you without shame.

. . .

Biographical information about Yellow Lark from Agathos Dorea (David Hunnicutt):

“Yellow Lark, a Lakota Sioux Chief, wrote the lamentation [prayer, above] in the midst of severe persecution by U.S. 7th Cavalry soldiers during the division and segregation of the indigenous tribes who were, at that time, inhabiting the southwestern portion of what is now South Dakota. Unable to come to a peaceful resolution, the years-long ordeal ended with the epic massacre that took place at Wounded Knee (1890) where three hundred Lakota Sioux men, women and children were executed by U.S. soldiers when they refused to be relocated to the Pine Ridge Reservation.

Yellow Lark’s lament was a divine plea to let peace and understanding prevail – even in the midst of severe persecution. Peaceful until the end, Chief Yellow Lark remains an iconic figure among the Lakota Sioux peoples to this very day.

Sadly, Wounded Knee still remains in the midst of the storm. With the average family income hovering near $12,000 annually, and an unemployment rate exceeding 80%, Wounded Knee is located in the poorest county in the United States of America.”

. . .

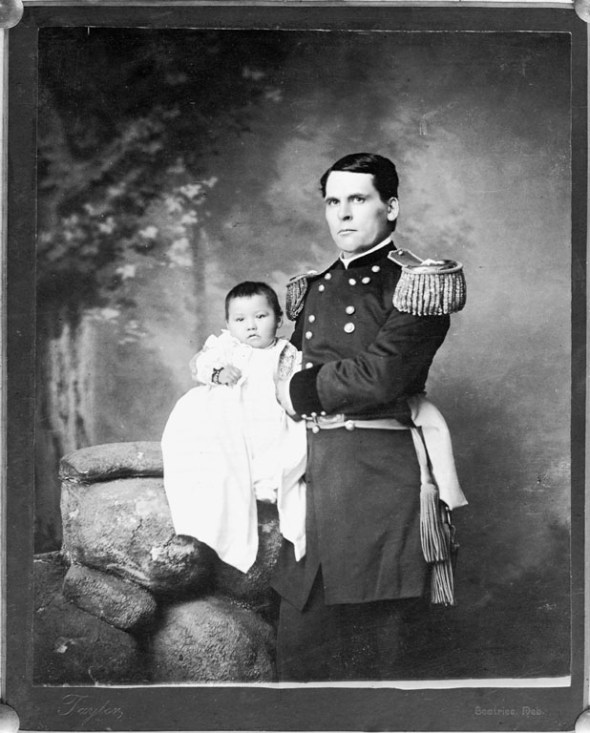

1891 Portrait of General L.W. Colby of Nebraska State Troops, holding baby girl Zintkala Nuni (Little Lost Bird), found on the Wounded Knee battlefield_This photograph is part of the long official history of the sentimentalization of Native genocide in the U.S.A.

. . .

Other songs/poems featured at ZP:

.

El Día del Indio Americano: unos poemas en guaraní y una reflexión sobre el lenguaje paraguayo

. . . . .