Alexander Best: “Notes on Normal”

Posted: March 11, 2013 Filed under: Alexander Best, English Comments Off on Alexander Best: “Notes on Normal”Alexander Best

“Notes on Normal”

.

The investment advertisement spoke of “smart risk”.

The sign on the bottled-water truck read: “Taste you can trust.”

At the townhouse complex, little notices

skewered the golf-green grass. They gave the date and time of

spraying and when the lawn would be “safe” again.

.

An office worker took two puffs of her cigarette then

tossed it onto the granite slab; it was back to the salt mines.

Two beggars stood nearby.

It didn’t get ugly over the “Hollywood butt”;

another one would be along in awhile.

. . .

Last night I awoke; it was slow and easy.

Down the hall, my neighbour picked out chords on his guitar.

The sound wasn’t loud; the house was unusually quiet.

3 a.m. Oh, but he hit the right notes!

I lay there and listened.

Then the music stopped.

.

My mind went this way and that. Those years returned, and

I knew there was no playing with the facts:

how ignorant I’d been — aggressive and stupid. And hadn’t it

gone on — and on.

Sleep came again, and took me.

. . .

Finally, he died.

Yes, he was old, but he’d been old for two-and-a-half decades,

since the age of forty-five.

The florid beard, silver in the black, had

given him a weight; and he’d been listened to, the difficult

so-and-so.

.

His Uncle. The only man left of that small,

snuffed-or-petered-out generation.

And these past five years, the beard gone, his face was

crunched and unintelligible.

.

What a waste.

So much could’ve happened that didn’t.

Yet so much had happened that had to.

And though he felt regret — fibrous and stony — he felt also

the uselessness of regrets.

.

That tightly-wound, far-flung bunch, their story was told.

And the estranged pair of them — Uncle and him —

they were one and complete.

. . .

I told someone off the other day, really laid it on thick.

She’d been burying me in bullshit for quite some time.

Who doesn’t she despise in our society?

.

Now I’m doubtful. I feel guilt. Was I perhaps too…

— no, I didn’t go far enough.

. . .

Oh privileged people —

when you extract head from navel, the

muffled hums and haws will become

well-spoken excuses.

.

Shut up and get on with it.

I expect more of thee!

. . .

Smug. It defines him.

Orthodoxy in all the obvious opinions; a crass certitude;

Hypocrisy.

And in one so young!

.

Facts. What he does with them is…

terrifying.

.

But now I say to myself:

Fool. Look around.

This is the only world he knows.

. . .

He was mistaken.

He’d thought it sensible to share so much — to be ‘modern’ —

with the old dear / battleaxe who’d given him Life.

But he didn’t know when to stop.

And now they are both of them

undignified.

.

How does one repair such damage?

.

Learning to be silent,

this will be hard work.

But the birds, cat and dog; the piano.

Maybe a ginger beer — she likes that —

in the backyard, when the hot days come.

It can be enough.

. . .

The funeral was a brisk affair; the woman’s decline had been

gradual, her death no surprise. Still, the hour was a solemn one.

He was the brother of someone who’d known the deceased,

a stranger in a small congregation, all of whom appeared to

be familiars. But afterward, he observed how

people departed in two distinct groups which had little or

nothing to say to one another.

.

His sister — the “someone who’d known the deceased” — was,

in truth, a very important person — mourner — in the pews.

But only the dead woman had known that.

.

Two square-looking, thirty-something women

— they’d sat in the front row —

attempted to pick him up as he

walked away from the cut-stone chapel.

One called him “distinguished”; the other, “hot”.

The coffin was carried down the steps, and

dayglo arrows marked the route to the grave.

It was a cold, early-spring afternoon.

. . .

The dream startled me awake.

I had to walk around, move myself here and there.

Downstairs, I put the kettle on.

.

First I was hunched over, then I was on the attack.

A door, off its hinges, was my shield, then my weapon.

There was no ground yet we weren’t falling.

There was no sky yet we kept breathing.

There was no room for us, in fact,

yet we had ample space for a struggle.

And who was we?

.

(2004)

. . . . .

Les Tendresses pour Yonge Street ( Tokens of Affection for Yonge Street )

Posted: March 10, 2013 Filed under: Alexander Best, English Comments Off on Les Tendresses pour Yonge Street ( Tokens of Affection for Yonge Street )

ZP_Corner of Yonge and Dundas, Toronto, 1972, looking south_The buildings on the right side were all demolished to make way for construction of The Eaton Centre which opened in 1977.

Alexander Best

LES TENDRESSES POUR YONGE STREET #1

( TOKENS OF AFFECTION FOR YONGE STREET…..)

.

Playoffs had begun; things were looking up for The Leafs…

Ten young guys, walking south to Carlton Street. Jock-ish

In their jerseys, ballcaps, space-age sneakers.

Cases of beer: treasure borne on shoulders and heads.

.

The creature of them halted in front of a shop-window: leopard-bikinis and

Lacey things. Big noise from the boys, sports-monkey-like.

.

Two teenage girls appeared on the sidewalk, slowing down, unsure.

(Awkward experiment: elegant hair, in the style of Marie-Antoinette, combined

with denim ensembles, ‘racing stripes’ down the sides of their pant-legs.)

.

The guys turned from window-display toward the girls, emitting a lusty

Oh Yeah!

One of the girls (shy one) couldn’t help but grin, showing

Microchip-circuitry of railroad-tracks; her mouth was a mess. The boys

Paused — taking in this ruination of her face — glanced among themselves,

Then voiced an even huge-r Oh Yeeaahhh of instinctual approval.

.

Girl’s friend rummaged for an itzy-bitzy disposable camera, held it out, simply

Aimed it at the mass of boys, and clicked.

Females, a-giggle, clumped north in their trendy ‘big-foot’ shoes. The

Manimal continued its way down the street.

. . .

LES TENDRESSES POUR YONGE STREET #2

“Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto.” / “I am a human being, I consider nothing that is human alien to me.”

(Publius Terentius Afer a.k.a. Terence – Roman playwright, 195–159 BCE)

.

I waited for the streetcar, in Monday’s midnight mist.

Cabbie pulled up, East-African guy, insisted I get in.

No money, I told him. Shift was over, he said. “You and I, we go in the

Same direction,” he assured me. Small as a boy, he was confident like a man.

.

Inside the car, passing the famous hockey-arena…

“Do you know this is a ‘gay area’ where you are standing on the corner?”

“Oh, really?” my mild response.

.

Left hand on the steering-wheel, he extended his right and placed the tips of his

Slim fingers on the vulnerable spot where my neck joins my breastbone.

“Let me see you” — his tone was oddly reverential.

.

I unbuttoned my shirt. He ran his hand over my chest and stomach.

“Ah,” he said gravely, “I am touching you, beautiful forest!”

The car skirted a grove of highrise apartment blocks, swinging onto the bridge that

Leads to a more sky-wide part of the city.

.

He patted my zipper: “Show me this one.”

He held my sex; it changed size. Chain of lights moved north, another south, on the

Riverside-highway below us. He considered me, in the palm of his hand:

“Alabaster plus two jewels,” he said. “ — but not so hard!” he added, joy flashing in his

Eyes. Our road lay arrow-straight, and luck – the traffic was serene.

.

I began to touch him, at the navel-gap in his shirt.

“No. This cannot. I am married.” — he spoke in a hush.

“Maybe I’m married, too,” I said. “You are wearing no ring,” he observed.

“True.” And I touched him again.

.

“Please do not,” he said firmly. Then, with a radiant smile showing teeth of

Stained ivory: “You will make us an accident…We must not have such a

Tragic romance!”

He refreshed me with these words. The car smelled of fake pine; radio-voice

Rhapsodized about a computer.

.

He caressed my thigh with his free hand. I told him my name; he, his; the

Bible came into it. When I was let out, he tapped a

Farewell-flourish on the car-horn.

.

A poet wrote: “It is only the sacred things that are worth touching.”

Thank you, stranger of the City, for revealing my body as sacred again.

In touching it you touched my soul.

ZP_Xaviera Hollander, the so-called Happy Hooker_She lived in Toronto during the mid-1970s and her liberated, guilt-free approach to sex was exactly what Toronto the Good needed_The Yonge Street Strip, mainly between Gerrard and Dundas, was the most honest zone in the city – a place of risqué fun and sleaze. Some of those qualities of random adventure and weird spontaneity still existed on the Yonge Street of the late 1990s – and the poet hopes he has captured a little of that in these three poems…

LES TENDRESSES POUR YONGE STREET #3

.

It was along by the Zanzibar Tavern…

Delivery van struck a man. Soft-hard sound, and he

Flipped through the air as if juggled.

.

Magnificent. People spun ’round.

He wasn’t out-cold; dusted himself off, embarrassed.

He began to walk; straightaway teetered, fell

Crumpled against a newspaper box.

Blood on his neck; humanity gawked.

.

An efficient person called the hospital on his pocket-phone.

The van-driver was sorry, impatient.

.

An old man and woman — he reedy, she petite — approached the

Injured one: “What is your name, dear?” said the woman, bending.

“What is my name? — What is my name?!?”

“Don’t, now…you’ve had a shock,” she said.

.

The man’s accent was distinctive; words in the shape of fear.

He’d’ve hailed from a dozen lands — to be precise.

.

The woman gestured for her mate to lean down with his good ear:

“He can stay with us…The children are gone — they needn’t know.”

Her husband’s eyebrows went up; held themselves aloft; settled down.

“Yes…I don’t see why not.”

.

The nameless fellow was arranged into the ambulance by two delicate,

Burly attendants. The couple was helped in next; one guy taking the

Old lady’s patent-leather handbag, the other the

Old gentleman’s cane.

.

(1999 – 2000)

Alexander Best: “The Soul in darkness”: 12 poems

Posted: March 10, 2013 Filed under: Alexander Best, English Comments Off on Alexander Best: “The Soul in darkness”: 12 poemsAlexander Best

“The Soul in darkness”

.

He’s destroyed his health — that much is plain.

A cough that never really leaves,

those hollows under his eyes.

Oh, it wasn’t any one thing he did…

but it all adds up.

.

Many of his habits were simple.

Taking his tea and a smoke by the window

while the sun rose, after a night of prowling.

He’d bring coffee to homeless guys with

winning, tooth-fractured smiles.

He’d talk to cats in the laneways; crouched down,

scratched them under their chins.

When money was scarce, still he managed

to buy drinks for charming strangers whose charm vanished

once they asked if he could lend them sixty bucks…

.

It was no one thing, true,

yet it all added up.

Life diminished him,

no matter what.

. . .

Each day brought some small joy or other.

What people called boredom

he called freedom to roam.

He listened to the water rush along the gutter toward the grate

— it was full of energy and romance.

At night when it rained,

he heard the wet wheels of traffic going this way or that

while he lay in his bed.

The city-hall tower was many blocks away,

but once in a while he heard the bell striking the hour,

and it pleased him.

He thought to himself:

this must be what it’s like to live forever.

. . .

They started out as friends.

Nearly always, it was good times.

Each trusted him whom he didn’t know.

By the end, they’d hurt one another a lot.

Accidental hurts? It was hard to tell

— but they hit their mark.

By the time it was really over, they’d become strangers

of the type that make up the faceless throng.

. . .

The number of times I’ve looked on people with desire.

Turning a corner. In a streetcar, an elevator.

At the cinema, courthouse.

In a glance, I’ve given myself to hundreds, and

I’ve taken thousands.

. . .

A beggar asked for change. I rummaged in my pockets.

He took a good look at me, in my old wool greatcoat;

declared: A blank cheque’ll do.

I smiled, gave him a two-dollar coin.

Noisily my awful boots squish-squished as I

strode up the street.

We both chuckled.

. . .

Nothing is clear to me.

Even the cloudless sky.

Every wall is a mirror.

So many years have passed that

some things are easier — time is thoughtful.

But nothing is clear.

. . .

The thought of living without him was unbearable.

And yet, that’s just what they’d been doing, for years.

Out of solitude came a knowledge he felt with his whole body:

their love was for all time.

Everywhere he went, he walked with a light step.

. . .

I waited. On the bench

by the massive oak tree.

Noone came.

I stayed too long,

my feet were like lead going home.

But memory calls.

I must go back.

. . .

The one dearest to him was ill.

Said his head throbbed, like it was his heart

— a loud beating,

outside his body.

He knew what that was like.

. . .

He went out on a limb — the old oak tree.

He sighed. Looked at the rope held coiled in his hand.

A nighthawk squawked.

That’s the wisdom I needed, he whispered aloud.

He lowered himself to the ground, with care

— didn’t want to sprain an ankle.

. . .

In the darkness of his room,

one after another, he strikes wooden matches,

leans each one against the inside of a small copper pot.

They spark, then swell to a crisp. And he says to himself:

Lovely they are, their whole life long.

. . .

Meal done, now’s the hour; some light in the sky still,

and man-made glows begin to warm each room.

Ahh,

spirit’s gone to my belly

— words don’t come…and that’s that.

.

Poem, shall we lie down, you and I?

And write ourselves tomorrow?

. . .

Editor’s note:

I wrote these poems in 2003 during the years when I went from one temporary job to the next, and was numb from emotional distress in my personal life. I seemed only to “camp” wherever I was living; I moved nine times between 1999 to 2010. Putting furniture out on the street, I would find what I needed for my next room on another curb. Everyone has crises in his or her life and we respond variously – with adequate action or with the inertia and blah mechanisms of Depression. I believe that this sequence of poems reflects – in its pensive, wistful, and “world-weary” tone – the influence of Constantine Cavafy (Konstantin Kavafis) whose poems in translation I was discovering at the time. These poems wrote themselves; my pen moved across the page of its own accord. The gift of composing Poetry has meant my survival; I am most grateful for that.

. . . . .

Poemas para El Día Internacional de la Mujer: una poetisa anishinaabe que deseamos honrar: Joanna Shawana / Poems for International Women’s Day: an Anishinaabe poet we wish to honour: Joanna Shawana

Posted: March 8, 2013 Filed under: English, Joanna Shawana, Joanna Shawana: poetisa anishinaabe/Anishinaabe poet, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: Poemas para El Día Internacional de la Mujer, Poems for International Women's Day Comments Off on Poemas para El Día Internacional de la Mujer: una poetisa anishinaabe que deseamos honrar: Joanna Shawana / Poems for International Women’s Day: an Anishinaabe poet we wish to honour: Joanna Shawana

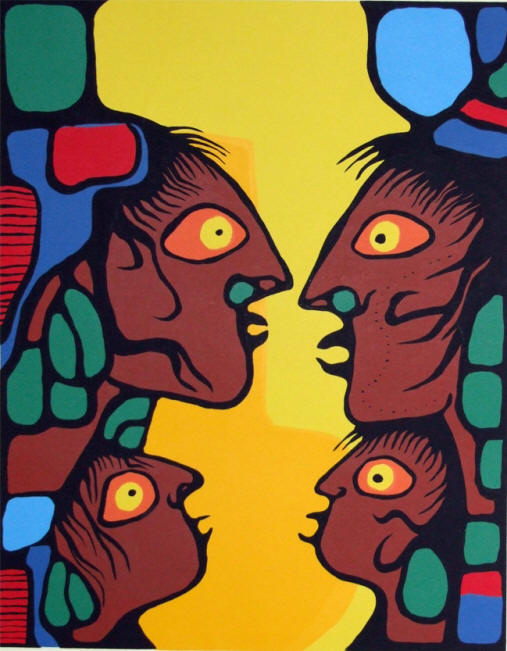

ZP_Manitoulin Island artist Daphne Odjig_Echoes of the Past_Daphne Odjig_Pintora indígena de la Isla de Manitoulin_Ecos del Pasado

Joanna Shawana / Niimkiigiihikgad-Kwe

(Anishinaabe poet from Wikwemikong, of the Ojibwe-Odawa First Nations Peoples, Mnidoo Mnis/Manitoulin Island, Ontario)

“Grandmother Moon”

.

During this cold dark night

Grandmother Moon sits high

Above the sky

.

Our Grandmother

Surrounded with stars

Emphasizing the life of the universe

.

As the night comes to end

Our Grandmother Moon slowly fades

Over the horizon

.

To greet Grandfather Sun

To greet him

As the new day begins

.

Grandmother Moon will rise again

She will shine and guide me on my path

As I walk on this journey.

. . .

Joanna Shawana / Niimkiigiihikgad-Kwe

(Poetisa anishinaabe de Wikwemikong, Mnidoo Mnis/Isla de Manitoulin, Ontario, Canadá)

“La Luna – Mi Abuela”

.

Durante esta noche fría y oscura

La Luna Mi Abuela se sienta

Alta en el cielo

.

Nuestra Abuela

Está rodeada de estrellas

Que hacen hincapié en la vida del universo

.

Como cierra la noche

Lentamente Nuestra Abuela La Luna destiñe

Encima del horizonte

.

Para dar la bienvenida al Abuelo El Sol

Para saludarle

Como comienza el nuevo día

.

Ella saldrá de nuevo, La Luna-Abuela,

Brillará y me guiará en mi camino

Como ando en este paso.

. . .

“All I Ask”

.

My fellow woman

My sisters

I am weak

I am hurt

All I ask of you is

Please

Hear what I have to say

Hear what I have to share

I am not here

To be looked down

I am not here

To be judged

For what had happened to me

All I ask of you is

Please

Hear what I have to share

My fellow women

My sisters

Listen to my words

See the pain in my eyes

All I ask of you is

Please

Hear what I have to say

Hear what I have to share

Help me

To get through my pain

Help me

To understand what is happening

Help me

To be a better person

So please

Hear what I have to say

Hear what I have to share.

. . .

“Todo lo que te pido…”

.

Mi compañera

Mis hermanas

Soy débil

Estoy dolida

Todo lo que te pido es

Por favor, escucha lo que tengo que decir

Escucha lo que tengo que compartirte

No estoy aquí

Para ser mirada por ustedes por encima del hombro

No estoy aquí

Para ser juzgada de

Lo que me había pasado

Todo lo que les pido es

Por favor, escuchen lo que tengo que compartirles,

Mis compañeras, mis hermanas,

Escuchen mis palabras

Vean el dolor en mis ojos

Todo lo que les pido es

Por favor,

Escuchen lo que tengo que decir

Escuchen lo que tengo que compartirles

Ayúdame a

Superar mi sufrimiento

Ayúdenme a

Comprender lo que pasa

Ayúdenme a

Ser una mejor persona

– Entonces,

Por favor,

Escucha lo que tengo que decirte,

Escuchen lo que tengo que compartir con ustedes…

. . .

“Hidden”

.

Hidden secrets

Hidden feelings

Hidden thoughts

.

Why do people need to hide

Their secrets

Their feelings and thoughts?

.

What are people afraid of?

Afraid of their own secrets

Afraid of their own feelings and thoughts

.

How can one person reveal?

To reveal their secrets

To reveal their feelings and thoughts

.

There is no reason to hide their secrets

There is no reason to hide their feelings

There is no reason to hide their thoughts.

. . .

“Escondido”

.

Secretos escondidos

Sentimientos escondidos

Pensamientos escondidos

.

¿Por qué la gente necesita ocultar algo?

Ocultar sus secretos, sus sentimientos y sus pensamientos

.

¿De qué tiene miedo la gente?

Tiene miedo de sus propios secretos,

Tiene miedo de sus corazonadas y sus ideas

.

¿Cómo revele una persona?

A revelar sus secretos

A revelar sus pensamientos

.

No hay razón para ser una tumba

No hay razón para engañarse a sí mismo sus sentimientos

No hay razón para esconder sus pensamientos.

. . .

“Wandering Spirit”

.

This wandering spirit of mine

Wanders off to the world of the unknown

The unknown of today and tomorrow

.

This wandering spirit of mine

Waits to hear your voice

Waits to listen for what will be said

.

This wandering spirit of mine

– Help me to discover the unknown

– Help me to understand

What the unknown needs to offer

.

Help this wandering spirit

That wanders off to the world of the unknown

That wonders what the future holds

.

This wandering spirit of mine

– Help me find peace and harmony

– Help me find tranquillity in life.

. . .

“Espíritu vagabundo”

.

Mi espíritu vagabundo

Se aleja al mundo de lo desconocido

Lo desconocido de hoy, de mañana

.

Este espíritu mío errante

Está aguardando tu voz

Está aguardando por lo que diremos

.

Espíritu mío, espíritu vagabundo

– Ayúdame a descubrir lo desconocido

– Ayúdame a entender

Lo que lo desconocido necesita ofrecerme

.

Ayúda a este espíritu errante

Que se aleja al mundo de lo desconocido

Y que se pregunta lo que va a contener el futuro

.

Este espíritu mío, mi espíritu andante

– Ayúdame a encontrar la paz y la armonía

– Ayúdame a encontrar la tranquilidad en la vida.

“Walk with Me”

.

Come and walk with me

On this path

Which I am walking on

.

We might slip and fall

To the cycle

That we once lived in

.

Let us

Help each other to understand

What we have been through

.

Let us walk together

Come and hold my hand

Hold it tight and never let go

.

Come and walk with me

Let us find what our future holds for us

Let us walk together on this path.

. . .

“Camina conmigo”

.

Ven – camina conmigo

A lo largo de este camino

Donde estoy caminando

.

Resbalemos y caigamos

Al ciclo

Que estaba nuestra vida

.

Ayudémonos a comprender,

La una a la otra,

Lo que salimos adelante, lo que sobrevivimos

.

Caminemos juntos,

Ven – toma mi mano –

Agárrate bien – nunca suéltame la mano

.

Ven – camina conmigo

Busquemos lo que habrá para nosotros en el futuro

Caminemos juntos en este camino.

. . .

Joanna Shawana moved down to Toronto in 1988. She began writing in 1994. A single parent, and now a grandmother, she has worked for an agency providing services to Native people in the city – Anishnawbe Health Toronto. Her bio. from her book of poems Voice of an Eagle states: A Catholic upbringing clashed with Native heritage teachings, which confused her path. However, through the years she gained more knowledge from her Native elders and began to clearly understand what it meant to be Nishnawbe Kwe (Native Woman). Thus, her journey in stabilizing her identity began… Joanna writes: ” When I look back and see what I have left behind, inside I cry for the little girl who witnessed that life, the teenager who was abused, and the woman who almost gave in, but I know now that my inner strength will never allow me to leave my path. Healing is a continuous part of life and it will be so until the day comes that the Creators call me. So as you travel along your path, remember – do not give in or give up! ”

.

Joanna Shawana fue víctima de mucho maltrato durante su juventud, también como una mujer joven. Desde 1988 ha vivido en la ciudad de Toronto donde trabaja con la agencia indígena Fortaleza de Anishnawbe Toronto. Dice: ” La curación es una parte continua de la vida y ésa será hasta que el día que me llamarán los Creadores. Entonces, mientras viajas en tu camino, recuerda – ¡no te des por vencido y no dejes de intentar! ”

.

Translations into Spanish / Traducciones en español: Alexander Best

. . . . .

Ngày Quốc tế Phụ nữ : Thơ Việt Nam / Poems for International Women’s Day : Vietnamese Voices : “I have crushed my dreams and turned them into a life…”

Posted: March 8, 2013 Filed under: English, Ngày Quốc tế Phụ nữ : Thơ Việt Nam / Poems for International Women's Day : Vietnamese Voices, Vietnamese | Tags: Poems for International Women's Day Comments Off on Ngày Quốc tế Phụ nữ : Thơ Việt Nam / Poems for International Women’s Day : Vietnamese Voices : “I have crushed my dreams and turned them into a life…”Dieu Nhan (Buddhist nun, 1041-1113)

“Birth, Old Age, Sickness, Death”

.

Birth, old age, sickness, death

Are commonplace and natural.

Should we seek relief from one,

Another will surely consume us.

Blind are those praying to Buddha,

Duped are those praying in Zen.

Pray not in Zen or to Buddha,

Speak not. Linger with silence.

.

(translation: Huu Ngoc, Lady Borton)

Dam Phuong (1881-1947)

“Flood Relief” (around 1928)

.

Harsh winds and the relentless rains drown

Districts that were once Thanh Hoa towns,

Swirling them down river, the water brown.

Warn the world: Silence is a stand,

.

Silence without opening your heart and hand.

Labourers reach out in crises of need,

Women with their gentleness take a lead,

Only then do the palace chiefs heed.

.

From this time on, we understand “kindness”,

Everyone joining in to ease public distress,

Those from humble trades with help appear,

Women draw on friends far and near.

.

(translation: Lady Borton)

Mong Tuyet (1914-2007)

“The price of rice in Tràng An” (1945)

(for Van Muoi, clerk at a flower shop in Tri Duc Garden)

.

I hear the price of rice in Trang An is high.

Starving for food, thirsting for life-saving rain,

Our friends and family in the centre and the north

Are desperately hoping rice will be sent from Dong Nai.

.

Grief dazes our nation’s artists.

You encouraged me to study poetry,

You want to release the ink of my poetic spirit.

Lost in a literary forest, I was building a road out.

.

I carried your books back home.

The people awaiting rice are in agony.

Sister, with my poor skills, how can I help?

You’d answer:

“I’ll sell literature, you sell flowers.”

.

(translation: Xuan Oanh, Lady Borton)

Tràng An is an old name for the city of HaNoi.

An important railway route and main road lay destroyed at the end of WWII,

hence rice did not reach enough people.

In Viet Nam, two million people had died of starvation by the end of the war.

.

Tran Thi My Hanh (born 1945)

“The road repair team at Jade Beauty Mountain” (1968)

.

Jade Beauty Mountain at Van River

Deserted at mid-day, buzzes with heat.

The mountain looks like a beautiful girl

Reclining, her eyes searching the azure sky.

.

Clouds like friends surround the Beauty.

Below are women workers from a road team,

Their youth and strength breaking a new trail,

Their hands skilled with hoes and quick with guns.

.

Pity the road circling the mountain,

Bomb craters slashing into bomb craters,

Olive trees, oak trees blackened with resin,

The birds scattered, ripped from their flocks,

Every rock on Beauty Mountain cringing in pain,

The earth tumbling down into the lowland paddies,

Night after night as the Beauty Mountain lies awake.

The women repairing the road are uneasy;

With torches, they search their way forward.

For them, a bite of dried bread is a delicious treat.

.

The green jackets that arrived yesterday

Were completely mended today (it was nothing).

Despite beating sun, pouring rain and bitter smoke,

The chop chop of hoes lifts skyward until after midnight.

.

The battlefield is here – The Front is here,

We fight the enemy for every inch of this road,

We shovel, shovel rock that smells of the mountain,

Our blood and sweat blending with the mountain’s basalt.

.

I hear the startling horns of passing trucks,

Feel my blood and the road’s blood pulse as one.

We, women with hearts as pure and dazzling as jade,

Stretch in a silhouette along the ridge of Beauty Mountain.

.

(translation: Lady Borton)

Jade Beauty Mountain is in northern Viet Nam’s Red River Delta. Route 1 is nearby,

and this major north-south road served as supply route during the U.S.–VietNam War.

Route 1 was bombed often by American planes.

Ha Phuong (born 1950)

“A meal by a stream” (1971)

.

A platoon of twelve

Four mess kits of cold rice

A packet of jerky

Wild vegetables from the forest

A minute to rest by a stream.

The fire hisses, as if urging the soup to boil –

.

With no dining table,

Some stand, some sit.

The steep mountain pass has quickened our hunger,

We hastily spread a leaf to make a small tray;

A mouthful of dry rice

When you’re hungry is delectable.

.

Jokes, teasing, the crisp sound of laughter,

A mess kit of cold rice, a few minutes’ pause.

“There’s still salt. The rice is tasty…”

The sound of laughter

The sound of laughter spreads.

.

Our unit’s meal is strangely joyful:

We’re far from our parents

But share the love of comrades.

On the Trail these days as we fight the Americans,

Our forest meals are delicious feasts.

.

(translation: Lady Borton)

Thuy Bac (1937-1996)

“Thread of Longing, Thread of Love” (1977)

.

Truong Son East

Truong Son West

.

On one side, sun burns

On the other, rain circles

.

I extend my hand

I open my hand

.

Impossible

To cover you

.

Pull this thread of love

To splice a roof

.

Pull this thread of longing

To weave a blue dome

.

Bend the Eastern Range

To cover you from the rain

.

Bend the Western Range

To spread a cool shadow

.

Canopy the sky with love

Of purest blue

.

I bend everything

Toward you.

.

(translation: Le Phuong, Wendy Erd)

The Ho Chi Minh Trail – a series of old mountain paths used for supply routes

by the North VietNamese during the U.S.–VietNam War –

passed through Truong Son (the Long Mountains).

.

Doan Ngoc Thu (born 1967)

“The city in the afternoon rain” (1992)

The city in the afternoon rain:

A beggar sits singing

A song from the war.

.

The city in the afternoon rain:

Roaming children

Vie for the bubbles they blow

And for fallen almonds.

.

The city in the afternoon rain:

Near a small roadside inn,

Cigarette ashes eddy with a burnt match

And a return ticket filled with nostalgia.

.

The city in the afternoon rain:

Suddenly I run into you,

You’re just as before – proud and harsh.

You step silently through the rain

To the beggar’s side

And weep –

At the song echoing the time of war.

.

(translation: Xuan Oanh, Lady Borton)

The war referred to is the U.S.–VietNam War.

. . .

. . .

Tran Mong Tu (born 1943)

“Lonely Cat” (1980)

.

The cat sprawls in the yard

Lonely, playing with sunlight.

Inside the window

Lonely, I’m watching him.

.

On grass green as jade,

Alone, his white back spins.

Sun shimmers down, drop by drop

The cat turns round my sadness.

.

I see myself in the glass,

A dim shadow, its outline vague:

The gate to marriage shut tight,

Imprisoning me so gently.

.

The cat has his corner of grass,

I, my dim pane.

We two, so small.

Our loneliness uncontained.

.

Dear cat in the sun,

Assuage my sadness.

My ancient homeland, my former lover,

Still soak my soul.

.

(translation: Le Phuong, Wendy Erd)

Tran Thi Khanh Hoi (born 1957)

“The Pregnant Woman” (1990)

She came to me,

Her eyes like the waves of a river in flood,

Her voice choking

At its source, then gushing like a waterfall,

Her breasts throbbing with milk about to flow,

Her unborn child kicking at my side.

In a few days, birth will release

The child’s hands and feet, its wails and cries,

But right now the mother sits waiting in weariness,

Like an arid field as the rising flood approaches its limit.

.

Angry at her husband, who won’t stop drinking,

She’s been pregnant throughout a season of hard labour.

Fears about her ill-treated baby

Have aged her,

Have left her fearful

Of the wealthy screaming for the money owed them,

Unmoved by the pain of a worried

Woman who is pregnant.

.

She came to me,

Seeking consolation, protection, sympathy.

What could I say when we can’t stop the inevitable?

The time is soon for this pregnant woman.

I swim through waves of silt from the flood,

Tonight –

.

(translation: Xuan Oanh, Lady Borton)

. . .

. . .

Huong Nghiem (born 1945)

“I don’t know” (1991)

.

Thinking of

The endless Universe,

I am suddenly aware:

The sun is very small.

Thinking of

Endless love,

I realize:

I am limited by you.

Instead of letting my own ego expand,

I am absorbed

In scrubbing

Your shirt collar clean.

But to what end

I don’t know.

.

(translation: Nguyen Quang Thieu, Lady Borton)

Le Thu (born 1940)

“My Poem” (1990)

.

I want you to be the ocean

Never ending, forever strange.

But I fear your heart may run too deep

For me to reach its limits.

.

I want you to be a river

Depositing rich soil on its banks.

But I fear the river’s length;

When does flowing water return?

.

I want to hear your words in a vow

To be sure you are mine forever.

But I fear flying high unfettered;

Yet how can I bind your wings?

.

I want you to be the moon,

Full on the fifteenth of the lunar month,

But I fear the next days’ waning;

Would our love also fade with the season?

.

So! You should be a poem

Gently entering my heart.

Then, our love forever young

Can be compassionate and complete!

.

(translation: Xuan Oanh, Lady Borton)

Nguyen Bao Chan (born 1969)

“For my father” (1995)

.

Looking at your hands

I see the lines

Splitting into the future and an exhausting past

I see also the sky of my youth,

How I drifted in dreams, following the moon and stars.

Father,

Time has rushed on

I have crushed my dreams and turned them into a life

I have held the broken pieces of your life in these frail hands

I have ground the shards to bluntness, ground them some more,

In order to live, love, and protect myself.

If ever I’m inattentive to you, broken

And reduced to pieces,

I know you will pick up the shards

Even though they cut your hands and give you pain.

.

(translation: Lady Borton)

Y Nhi (born 1944)

“Longing” (1998)

To leave

like a boat pulling away from a dock at dawn

while waves touch the sandbar, saying goodbye

.

Like a still-green leaf torn from a branch

leaving only a slight break in the wood

.

Like a deep purple orchid

gradually fading and

then one day closing off like an old cocoon

.

To leave

like a radiant china vase displayed on a brightly lit shelf,

as the vase starts to crack

.

Like a lovely poem ripped from a newspaper

first sad

then elated

as it flies off like a butterfly in late summer

.

Like an engagement ring

slipping off a finger

and hiding itself among pebbles

.

To leave

like a woman walking away from her love.

.

(translation: Thuy Dinh, Martha Collins)

. . .

. . .

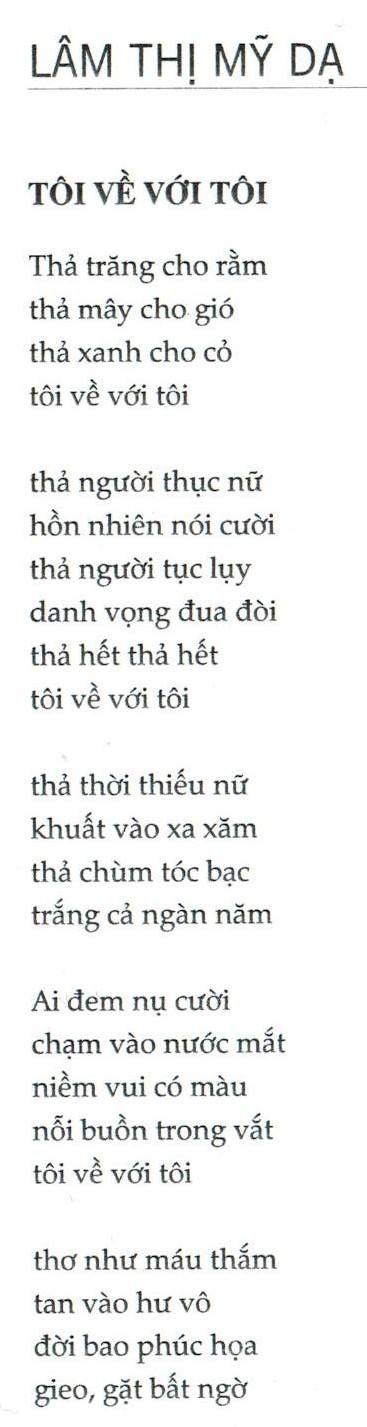

Lam Thi My Da (born 1949)

“I return to myself” (2004)

.

Free the moon for its fullness,

Free the clouds for the wind,

Free the colour green for the grass.

I return to myself.

.

Free the gentle girls

To be unaffected;

Free people from suffering,

From competing for fame,

Free them all, free them all.

I return to myself.

.

Free teenage girls

From hiding away,

Free grey hair

To be white forever.

.

Everyone carries a smile

To chase away tears.

Joy has colours,

Sorrow is transparent.

I return to myself.

.

Poetry is the scarlet of blood

Seeping into the voice.

Life has untold blessings and disasters;

We sow, then unexpectedly reap.

.

The weary can never rest,

The pained can no longer cry,

The silent ones are like shadows.

I return to myself.

.

Luckily, a small child

Remains inside the soul,

Her gaze fresh,

Shimmering at the roots,

Her heart still naive.

I return to myself.

.

(translation: Xuan Oanh, Lady Borton)

. . . . .

All of the above translations from Vietnamese into English are the copyright © of the following translators:

Huu Ngoc, Lady Borton, Le Phuong, Martha Collins, Nguyen Quang Thieu, Thuy Dinh, Wendy Erd, and Xuan Oanh.

This compilation of poems is the copyright © of editors Nguyen Thi Minh Ha, Nguyen Thi Thanh Binh, and Lady Borton.

. . . . .

कबीर “The Songs of Kabir”: translations by Rabindranath Tagore and Robert Bly

Posted: February 28, 2013 Filed under: English, Kabir Comments Off on कबीर “The Songs of Kabir”: translations by Rabindranath Tagore and Robert Bly

“The Kabir Book: Forty-Four of the Ecstatic Poems of Kabir” (1977) – versions by Robert Bly, based on Rabindranath Tagore’s “The Songs of Kabir” (1915).

.

“The Songs of Kabir” (published in 1915) translated by Rabindranath Tagore, assisted by Evelyn Underhill, from Bengali versions of the original Kabir Hindi-language poems.

.

In the selection that follows, Bly’s versions of Kabir are first, followed by Tagore’s. The first-verse quotations – which appear between the Bly and the Tagore – and each with a Roman numeral then a number, refer to Tagore’s source for his Kabir poems – that is, Santiniketana: Kabir by Sri Kshitimohan Sen, in 4 parts, Brahmacharyasrama, Bolpur, published in 1910-1911.

. . .

Friend, hope for the Guest while you are alive.

Jump into experience while you are alive.

Think…and think…while you are alive.

What you call “salvation” belongs to the time before death.

.

If you don’t break your ropes while you’re alive,

do you think

ghosts will do it after?

.

The idea that the soul will join with the ecstatic

just because the body is rotten –

that is all fantasy.

What is found now is found then.

If you find nothing now,

you will simply end up with an apartment in the City of Death.

If you make love with the divine now, in the next life

you will have the face of satisfied desire.

.

So plunge into the truth, find out who the Teacher is,

believe in the Great Sound!

Kabir says this:

When the Guest is being searched for,

it is the intensity of the longing for the Guest that

does all the work.

Look at me, and you will see a slave of that intensity.

.

I. 57. sâdho bhâî, jîval hî karo âs’â

.

O Friend! hope for Him whilst you live, know whilst you live,

understand whilst you live: for in life deliverance abides.

If your bonds be not broken whilst living, what hope of deliverance in death?

It is but an empty dream, that the soul shall have union with Him

because it has passed from the body:

If He is found now, He is found then,

If not, we do but go to dwell in the City of Death.

If you have union now, you shall have it hereafter.

Bathe in the truth, know the true Guru, have faith in the true Name!

Kabîr says: “It is the Spirit of the quest which helps;

I am the slave of this Spirit of the quest.”

. . .

Friend, please tell me what I can do about this world I hold to,

and keep spinning out!

I gave up sewn clothes, and wore a robe,

but I noticed one day the cloth was well woven.

So I bought some burlap, but I still

throw it elegantly over my shoulder.

I pulled back my sexual longings,

and now I discover that I’m angry a lot.

I gave up rage, and now I notice

that I am greedy all day.

I worked hard at dissolving my greed,

and now I am proud of myself.

When the mind wants to break its link with the world

it still holds on to one thing.

Kabir says:

Listen, my friend,

there are very few that find the path!

.

I. 63. avadhû, mâyâ tajî na jây

.

Tell me, Brother, how can I renounce Maya?

When I gave up the tying of ribbons, still I tied my garment about me:

When I gave up tying my garment, still I covered my body in its folds.

So, when I give up passion, I see that anger remains;

And when I renounce anger, greed is with me still;

And when greed is vanquished, pride and vainglory remain;

When the mind is detached and casts Maya away, still it clings to the letter.

Kabîr says,

“Listen to me, dear Sadhu! the true path is rarely found.”

. . .

I played for ten years with the girls my own age,

but now I am suddenly in fear.

I am on the way up some stairs – they are high.

Yet I have to give up my fears

if I want to take part in this love.

.

I have to let go the protective clothes

and meet him with the whole length of my body.

My eyes will have to be the love-candles this time.

Kabir says:

Men and women in love will understand this poem.

If what you feel for the Holy One is not desire,

then what’s the use of dressing with such care,

and spending so much time making your eyelids dark?

.

I. 131. nis’ din khelat rahî sakhiyân sang

.

I played day and night with my comrades, and now I am greatly afraid.

So high is my Lord’s palace, my heart trembles to mount its stairs:

yet I must not be shy, if I would enjoy His love.

My heart must cleave to my Lover; I must withdraw my veil,

and meet Him with all my body:

Mine eyes must perform the ceremony of the lamps of love.

Kabîr says:

“Listen to me, friend: he understands who loves.

If you feel not love’s longing for your Beloved One,

it is vain to adorn your body, vain to put unguent on your eyelids.”

. . .

I have been thinking of the difference

between water

and the waves on it.

Rising, water’s still water, falling back,

it is water, will you give me a hint

how to tell them apart?

.

Because someone has made up the word

“wave”, do I have to distinguish it

from water?

.

There is a Secret One inside us;

the planets in all the galaxies

pass through his hands like beads.

.

That is a string of beads one should look at with

luminous eyes.

.

II. 56. dariyâ kî lahar dariyâo hai jî

.

The river and its waves are one

surf: where is the difference between the river and its waves?

When the wave rises, it is the water; and when it falls, it is the same water again.

Tell me, Sir, where is the distinction?

Because it has been named as wave, shall it no longer be considered as water?

.

Within the Supreme Brahma, the worlds are being told like beads:

Look upon that rosary with the eyes of wisdom.

. . .

What has death and a thick body dances before

what has no thick body and no death.

The trumpet says: “I am you.”

The spiritual master arrives and bows down to the

beginning student.

Try to live to see this!

.

II. 85. nirgun âge sargun nâcai

.

Before the Unconditioned, the Conditioned dances:

“Thou and I are one!” this trumpet proclaims.

The Guru comes, and bows down before the disciple:

This is the greatest of wonders.

. . .

Why should I flail about with words, when love

has made the space inside me full of light?

I know the diamond is wrapped in this cloth, so why

should I open it all the time and look?

When the pan was empty, it flew up; now that it’s

full, why bother weighing it?

.

The swan has flown to the mountain lake!

Why bother with ditches and holes anymore?

The Holy One lives inside you –

why open your other eyes at all?

.

Kabir will tell you the truth: Listen, brother!

The Guest, who makes my eyes so bright,

has made love with me.

.

II. 105. man mast huâ tab kyon bole

.

Where is the need of words, when love has made drunken the heart?

I have wrapped the diamond in my cloak; why open it again and again?

When its load was light, the pan of the balance went up: now it is full,

where is the need for weighing?

The swan has taken its flight to the lake beyond the mountains;

why should it search for the pools and ditches anymore?

Your Lord dwells within you: why need your outward eyes be opened?

Kabîr says: “Listen, my brother! my Lord, who ravishes my eyes,

has united Himself with me.”

Cuando se forman carámbanos en el tejaroz llega pronto la Primavera. When icicles form at the eaves Spring can’t be far off…Toronto, February 28th, 2013

Friend, wake up!

Why do you go on sleeping?

The night is over – do you want to lose the day the same way?

Other women who managed to get up early have

already found an elephant or a jewel…

So much was lost already while you slept…

And that was so unnecessary!

.

The one who loves you understood, but you did not.

You forgot to make a place in your bed next to you.

Instead you spent your life playing.

In your twenties you did not grow

because you did not know who your Lord was.

Wake up! Wake up!

There’s no-one in your bed –

He left you during the long night.

.

Kabir says: The only woman awake is the woman who has heard the flute!

.

II. 126. jâg piyârî, ab kân sowai

.

O Friend, awake, and sleep no more!

The night is over and gone, would you lose your day also?

Others, who have wakened, have received jewels;

O foolish woman! you have lost all whilst you slept.

Your lover is wise, and you are foolish, O woman!

You never prepared the bed of your husband:

O mad one! you passed your time in silly play.

Your youth was passed in vain, for you did not know your Lord;

Wake, wake! See! your bed is empty: He left you in the night.

Kabîr says:

“Only she wakes, whose heart is pierced with the arrow of His music.”

. . .

Knowing nothing shuts the iron gates; the new love opens them.

The sound of the gates opening wakes the beautiful woman asleep.

Kabir says:

Fantastic! Don’t let a chance like this go by!

.

I. 50. bhram kâ tâlâ lagâ mahal re

.

The lock of error shuts the gate, open it with the key of love:

Thus, by opening the door, thou shalt wake the Belovéd.

Kabîr says:

“O brother! do not pass by such good fortune as this.”

. . .

There is nothing but water in the holy pools.

I know – I have been swimming in them.

All the gods sculpted of wood or ivory can’t say a word.

I know – I have been crying out to them.

The Sacred Books of the East are nothing but words.

I looked through their covers one day sideways.

What Kabir talks of is only what he has lived through.

If you have not lived through something – it is not true.

.

I. 79. tîrath men to sab pânî hai

.

There is nothing but water at the holy bathing places;

and I know that they are useless,

for I have bathed in them.

The images are all lifeless, they cannot speak; I know,

for I have cried aloud to them.

The Purana and the Koran are mere words;

lifting up the curtain, I have seen.

Kabîr gives utterance to the words of experience;

and he knows very well that all other things are untrue.

. . .

When my friend is away from me, I am depressed;

nothing in the daylight delights me,

sleep at night gives no rest –

who can I tell about this?

.

The night is dark, and long…hours go by…

because I am alone, I sit up suddenly,

fear goes through me…

.

Kabir says:

Listen, my friend,

there is one thing in the world that satisfies,

and that is a meeting with the Guest.

.

I. 130. sâîn vin dard kareje hoy

.

When I am parted from my Belovéd, my heart is full of misery:

I have no comfort in the day, I have no sleep in the night.

To whom shall I tell my sorrow?

The night is dark; the hours slip by.

Because my Lord is absent, I start up and tremble with fear.

Kabîr says: “Listen, my friend! there is no other satisfaction,

save in the encounter with the Belovéd.”

. . .

The spiritual athlete often changes the colour of his clothes,

and his mind remains grey and loveless.

.

He sits inside a shrine room all day,

so that the Guest has to go outdoors and praise the rocks.

.

Or he drills holes in his ears, his beard grows enormous and matted –

people mistake him for a goat…

He goes out into wilderness areas, strangles his impulses,

and makes himself neither male nor female…

.

He shaves his skull, puts his robe in an orange vat,

reads the Bhagavad-Gita –

and becomes a terrific talker.

.

Kabir says:

Actually, you are going in a hearse to the country of death –

bound hand and foot!

.

I. 20. man na rangâye

.

The Yogi dyes his garments, instead of dyeing his mind in the colours of love:

He sits within the temple of the Lord, leaving Brahma to worship a stone.

He pierces holes in his ears, he has a great beard and matted locks, he looks like a goat:

He goes forth into the wilderness, killing all his desires, and turns himself into an eunuch:

He shaves his head and dyes his garments; he reads the Gîtâ and becomes a mighty talker.

Kabîr says: “You are going to the doors of death, bound hand and foot!”

. . .

I don’t know what sort of a God we have been talking about.

.

The caller calls in a loud voice to the Holy One at dusk.

Why? Surely the Holy One is not deaf.

He hears the delicate anklets that ring on the feet of

an insect as it walks.

.

Go over and over your beads, paint weird designs on your forehead,

wear your hair matted, long, and ostentatious,

but when deep inside you there is a loaded gun,

how can you have God?

.

I. 9. nâ jâne sâhab kaisâ hai

.

I do not know what manner of God is mine.

The Mullah cries aloud to Him: and why? Is your Lord deaf? The

subtle anklets that ring on the feet of an insect when it moves

are heard of Him.

Tell your beads, paint your forehead with the mark of your God,

and wear matted locks long and showy: but a deadly weapon is in

your heart, and how shall you have God?

. . .

The Holy One disguised as an old person in a cheap hotel

goes out to ask for carfare.

But I never seem to catch sight of him.

If I did, what would I ask him for?

He has already experienced what is missing in my life.

Kabir says:

I belong to this old person.

Now let the events about to come – come!

.

III. 89. mor phakîrwâ mângi jây

.

The Beggar goes a-begging, but

I could not even catch sight of Him:

And what shall I beg of the Beggar He gives without my asking.

Kabîr says: “I am His own: now let that befall which may befall!”

. . .

The Guest is inside you, and also inside me;

you know the sprout is hidden inside the seed.

We are all struggling; none of us has gone far.

Let your arrogance go, and look around inside.

.

The blue sky opens out farther and farther,

the daily sense of failure goes away,

the damage I have done to myself fades,

a million suns come forward with light,

when I sit firmly in that world.

.

I hear bells ringing that no-one has shaken,

inside “love” there is more joy than we know of,

rain pours down, although the sky is clear of clouds,

there are whole rivers of light.

The universe is shot through in all parts by a single sort of love.

how hard it is to feel that joy in all our four bodies!

.

Those who hope to be reasonable about it fail.

The arrogance of reason has separated us from that love.

With the word “reason” you already feel miles away.

.

How lucky Kabir is, that surrounded by all this joy

he sings inside his own little boat.

His poems amount to one soul meeting another.

These songs are about forgetting dying and loss.

They rise above both coming in and going out.

.

II. 90. sâhab ham men, sâhab tum men

.

The Lord is in me, the Lord is in you, as life is in every seed.

O servant! put false pride away, and seek for Him within you.

A million suns are ablaze with light,

The sea of blue spreads in the sky,

The fever of life is stilled, and all stains are washed away;

when I sit in the midst of that world.

Hark to the unstruck bells and drums! Take your delight in love!

Rains pour down without water, and the rivers are streams of light.

One Love it is that pervades the whole world, few there are who

know it fully:

They are blind who hope to see it by the light of reason, that

reason which is the cause of separation–

The House of Reason is very far away!

How blessed is Kabîr, that amidst this great joy he sings within

his own vessel.

It is the music of the meeting of soul with soul;

It is the music of the forgetting of sorrows;

It is the music that transcends all coming in and all going

forth.

. . .

The small ruby everyone wants has fallen out on the road.

Some think it is east of us, others – west of us.

Some say, “among primitive earth rocks:, others – “in the deep waters.”

Kabir’s instinct told him it was inside, and what it was worth,

And he wrapped it up carefully in his heart cloth.

.

III. 26. tor hîrâ hirâilwâ kîcad men

.

The jewel is lost in the mud, and all are seeking for it;

Some look for it in the east, and some in the west;

some in the water and some amongst stones.

But the servant Kabîr has appraised it at its true value,

and has wrapped it with care in the end of the mantle of his heart.

. . . . . . . . . .

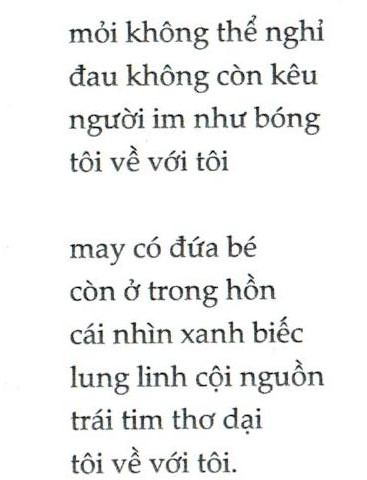

“Even amidst fierce flames the golden lotus can be planted”: Sylvia Plath and “Daddy” on Valentine’s Day

Posted: February 14, 2013 Filed under: English, Spanish, Sylvia Plath Comments Off on “Even amidst fierce flames the golden lotus can be planted”: Sylvia Plath and “Daddy” on Valentine’s Day“Even amidst fierce flames the golden lotus can be planted.”

(Inscription on Sylvia Plath’s headstone)

.

It’s fifty years since her suicide, February 11th, 1963, at the age of 30, and Boston, Massachusetts-born Sylvia Plath’s confessional poem “Daddy” remains powerful still. It’s easy to forget – now that we’ve experienced a generation of much soul-baring in society (and of really really private stuff) in tell-all autobiographies, Oprah Winfrey interviews, etc., that what Plath was doing here was rare in Anglo-American poetry – where decorum and a certain “cool” or at least emotionally-neutral treatment of the subject of the poem predominated. In its way “Daddy” is a kind of turbulent, definitely heart-felt Valentine letter from a daughter to a father. (And some scholars have suggested that the anger in the poem is also directed at Plath’s poet-husband, Ted Hughes, who was brazen about carrying on an affair when the couple had two infant children.) It was while staying at the Yaddo artists’ retreat in New York State in 1959 that Plath had learned “to be true to my own weirdnesses”. Yet a poem such as “Daddy” – drawn from such deeply personal material (the death of her German father, his emotional repression, her angry love for him) – would not come till just before the young poetess – depressed and suicide-prone from her early 20s onward – finally “did it”. Plath’s use of Holocaust imagery combined with nursery-rhyme poem-metre makes “Daddy” a jolting poem for any first-time reader.

. . .

La poetisa estadounidense Sylvia Plath se suicidó hace cincuenta años. Su poema “Papi” permanece como buen ejemplo de su poesía confesional. Casi es una carta apasionada, del amor y enojo, una carta de Valentín muy rara para su padre alemán que ya había muerto. (Y aunque Plath escriba de su padre como si fuera un Nazi – él no fue un Nazi.) En 1982 Plath fue la primera poeta en ganar el premio Pulitzer póstumo (por Poemas Completos, publicado después de su muerte).

.

Sylvia Plath (1932 – 11 de febrero, 1963)

“Papi”

.

Ya no, ya no,

ya no me sirves, zapato negro,

en el cual he vivido como un pie

durante treinta años, pobre y blanca,

sin atreverme apenas a respirar o hacer achís.

.

Papi: he tenido que matarte.

Te moriste antes de que me diera tiempo…

Pesado como el mármol, bolsa llena de Dios,

lívida estatua con un dedo del pie gris,

del tamaño de una foca de San Francisco.

.

Y la cabeza en el Atlántico extravagante

en que se vierte el verde legumbre sobre el azul

en aguas del hermoso Nauset.

Solía rezar para recuperarte.

Ach, du.

.

En la lengua alemana, en la localidad polaca

apisonada por el rodillo

de guerras y más guerras.

Pero el nombre del pueblo es corriente.

Mi amigo polaco

.

dice que hay una o dos docenas.

De modo que nunca supe distinguir dónde

pusiste tu pie, tus raíces:

nunca me pude dirigir a ti.

La lengua se me pegaba a la mandíbula.

.

Se me pegaba a un cepo de alambre de púas.

Ich, ich, ich, ich,

apenas lograba hablar:

Creía verte en todos los alemanes.

Y el lenguaje obsceno,

.

una locomotora, una locomotora

que me apartaba con desdén, como a un judío.

Judío que va hacia Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen.

Empecé a hablar como los judíos.

Creo que podría ser judía yo misma.

.

Las nieves del Tirol, la clara cerveza de Viena,

no son ni muy puras ni muy auténticas.

Con mi abuela gitana y mi suerte rara

y mis naipes de Tarot, y mis naipes de Tarot,

podría ser algo judía.

Siempre te tuve miedo,

con tu Luftwaffe, tu jerga pomposa

y tu recortado bigote

y tus ojos arios, azul brillante.

Hombre-panzer, hombre-panzer: oh Tú…

.

No Dios, sino un esvástica

tan negra, que por ella no hay cielo que se abra paso.

Cada mujer adora a un fascista,

con la bota en la cara; el bruto,

el bruto corazón de un bruto como tú.

.

Estás de pie junto a la pizarra, papi,

en el retrato tuyo que tengo,

un hoyo en la barbilla en lugar de en el pie,

pero no por ello menos diablo, no menos

el hombre negro que

.

me partió de un mordisco el bonito corazón en dos.

Tenía yo diez años cuando te enterraron.

A los veinte traté de morir

para volver, volver, volver a ti.

Supuse que con los huesos bastaría.

Pero me sacaron de la tumba,

y me recompusieron con pegamento.

Y entonces supe lo que había que hacer.

.

Saqué de ti un modelo,

un hombre de negro con aire de Meinkampf,

.

e inclinación al potro y al garrote.

Y dije sí quiero, sí quiero.

De modo, papi, que por fin he terminado.

El teléfono negro está desconectado de raíz,

las voces no logran que críe lombrices.

.

Si ya he matado a un hombre, que sean dos:

el vampiro que dijo ser tú

y me estuvo bebiendo la sangre durante un año,

siete años, si quieres saberlo.

Ya puedes descansar, papi.

.

Hay una estaca en tu negro y grasiento corazón,

y a la gente del pueblo nunca le gustaste.

Bailan y patalean encima de ti.

Siempre supieron que eras tú.

Papi, papi, hijo de puta, estoy acabada.

Sylvia Plath (1932 – February 11th, 1963)

“Daddy”

.

You do not do, you do not do

Any more, black shoe

In which I have lived like a foot

For thirty years, poor and white,

Barely daring to breathe or A-choo.

.

Daddy, I have had to kill you.

You died before I had time—

Marble-heavy, a bag full of God,

Ghastly statue with one gray toe

Big as a Frisco seal

.

And a head in the freakish Atlantic

Where it pours bean green over blue

In the waters off the beautiful Nauset.

I used to pray to recover you.

Ach, du.

.

In the German tongue, in the Polish town

Scraped flat by the roller

Of wars, wars, wars.

But the name of the town is common.

My Polack friend

.

Says there are a dozen or two.

So I never could tell where you

Put your foot, your root,

I never could talk to you.

The tongue stuck in my jaw.

.

It stuck in a barb wire snare.

Ich, ich, ich, ich,

I could hardly speak.

I thought every German was you.

And the language obscene

.

An engine, an engine,

Chuffing me off like a Jew.

A Jew to Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen.

I began to talk like a Jew.

I think I may well be a Jew.

.

The snows of the Tyrol, the clear beer of Vienna

Are not very pure or true.

With my gypsy ancestress and my weird luck

And my Taroc pack

I may be a bit of a Jew.

.

I have always been scared of you,

With your Luftwaffe, your gobbledygoo.

And your neat mustache

And your Aryan eye, bright blue.

Panzer-man, panzer-man, O You –

.

Not God but a swastika

So black no sky could squeak through.

Every woman adores a Fascist,

The boot in the face, the brute

Brute heart of a brute like you.

.

You stand at the blackboard, daddy,

In the picture I have of you,

A cleft in your chin instead of your foot

But no less a devil for that, no not

Any less the black man who

.

Bit my pretty red heart in two.

I was ten when they buried you.

At twenty I tried to die

And get back, back, back to you.

I thought even the bones would do.

.

But they pulled me out of the sack,

And they stuck me together with glue.

And then I knew what to do.

I made a model of you,

A man in black with a Meinkampf look

.

And a love of the rack and the screw.

And I said I do, I do.

So daddy, I’m finally through.

The black telephone’s off at the root,

The voices just can’t worm through.

.

If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two –

The vampire who said he was you

And drank my blood for a year,

Seven years, if you want to know.

Daddy, you can lie back now.

.

There’s a stake in your fat black heart

And the villagers never liked you.

They are dancing and stamping on you.

They always knew it was you.

Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.

. . . . .

“Orfeu Negro” and the origins of Samba + Wilson Batista’s “Kerchief around my neck” and Noel Rosa’s “Idle youth”

Posted: February 8, 2013 Filed under: English, Noel Rosa, Orfeu Negro and the origins of Samba + Wilson Batista's “Kerchief around my neck” and Noel Rosa's “Idle youth”, Portuguese, Wilson Batista | Tags: Black History Month photographs Comments Off on “Orfeu Negro” and the origins of Samba + Wilson Batista’s “Kerchief around my neck” and Noel Rosa’s “Idle youth”

ZP_Breno Mello, 1931 – 2008, as Orpheus in the 1959 Marcel Camus film, Orfeu Negro_Mello was a soccer player whom Camus chanced to meet on the street in Rio de Janeiro. Camus decided to cast the non-actor as the lead in the film. Mello turned out to be exactly right for the role of the star-crossed Everyman enchanted by tricky Fate – his Love is stalked by Death.

- ZP_Marpessa Dawn, American-born actress of Black and Filipino heritage who played Eurydice opposite Breno Mello as Orpheus in the 1959 film Orfeu Negro. She is seen here in a photograph taken at the 1959 Cannes Film Festival. Dawn would later have a bizarre role as Mama Communa in the often-censored or banned 1974 Canadian film by European director Dusan Makavejev – Sweet Movie. A long way from her role in Orfeu Negro…yet she brought something of her beautiful wholesomeness even to the disturbing scenarios of Sweet Movie. Marpessa Dawn died in 2008 at the age of 74 in Paris.

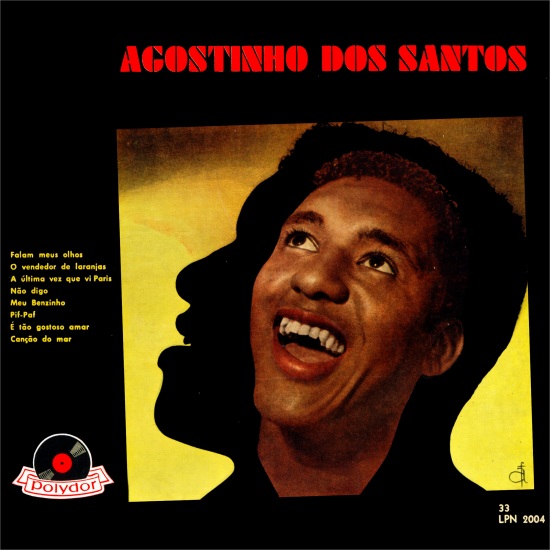

ZP_a 1956 record album by Agostinho Dos Santos who sang the now internationally famous songs from the 1959 film Orfeu Negro_ A Felicidade and Manhã de Carnaval

Orfeu Negro (Black Orpheus), a 1959 film in Portuguese with subtitles, was directed by Marcel Camus in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Set at Carnaval time, it featured a mainly Black cast and told a modern Brazilian version of the Greek legend of Orpheus and Eurydice. The Morro da Babilônia “favela” (Babylon Hill “slum”) was used for filming many scenes. Orfeu Negro is a nearly perfect film. Exuberant and pensive, charming and mysterious, it is an engrossing story of doomed Lovers accompanied by the exquisitely-intimate singing of Agostinho Dos Santos of Luiz Bonfá’s songs in the then-nascent bossa nova style. And add to all that the “crazy Life force” pulse of Samba at night in the streets…

Samba – the word – is derived via Portuguese from the West-African Bantu word “semba”, which means “invoke the spirit of the ancestors”. Originating in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil, by the 1920s the Samba sound was emerging with usually a 2/4 tempo, the use of choruses with hand-claps plus declaratory verses, and much of it in batucada rhythm which included African-influenced percussion such as tamborim, repinique, cuica, pandeiro and reco-reco adding many layers to the music. The “voice” of the cavaquinho (which is like a ukulele) provided a pleasing contrast and a non-stop little wooden whistle, the apito, made the urgent breath of human beings palpable.

In the late 1920s in the Rio favela of Mangueira – among others – there began one of the earliest “samba schools”, initiating the transformation of Rio de Janeiro’s Carnaval (which had existed on and off since the 18th century but which was neither a large city-wide event nor one with a strong Black Brazilian influence). In the 21st century, of course, Carnaval in Rio de Janeiro has become the most massive festival in the world; in 2011, for example, close to 5 million people took part, with more than 400,000 of them being foreign visitors. But back in the 1920s…the original Mangueira cordões or cords (also known as blocos or blocks) consisted of groups of masked participants, all men, who were led down the street by a “teacher” blowing an apito whistle. Following them was a mobile orchestra of percussion. In the years that followed the Carnaval procession expanded to include 1. the participation of women 2. floats 3. a theme 4. a mestre-sala (master of ceremonies) and a porta-bandeira (flag-bearer).

Notable early composers and singers of Samba (sambistas) included Pixinguinha, Cartola, Ataulfo Alves and Jamelão among men and Clementina de Jesus, Carmelita Madriaga, Dona Ivone Lara and Jovelina Pérola Negra among women. But this is just the beginning of a long list…

The “fathers” of Samba were Rio musicians but the “mothers” of Samba were the Tias Baianas or the Aunties from Salvador da Bahia (a smaller though culturally rich city further up the Atlantic Coast). Hilária Batista de Almeida, also known as Tia Ciata (1854-1924), was born in Bahia but lived in Rio de Janeiro from the 1870s onward. Involved in persecuted “roots” rituals, she became a Mãe Pequena or Little Mother – Iyakekerê in the Yoruba language – one type of venerated priestess in the Afro-Brazilian religion, Candomblé. The Bahia African rhythms that were crucial to her ceremonies at Rua Visconde de Itaúna, number 177, were incorporated into their compositions by musicians such as Pixinguinha and Donga who were used to playing the maxixe (a 19th-century tango-like dance still popular in Rio in the early 20th century). That musical fusion was the birth of samba carioca – the early Samba sound of Rio. Pelo Telefone (“Over the Telephone”), from 1917, the humorous lyrics of which concern a gambling house (casa de jogo do bicho) and someone waiting for a telephone call tipping him off that the police are about to carry out a raid, is considered the first true Samba song.

ZP_Os Oito Batutas_The Eight Batons or Eight Cool Guys_around 1920. These Rio musicians had played maxixes and choros for bourgeois theatre-goers in the lobby at intermissions. They began to add ragtime and foxtrot numbers, the latest American imports. But in their spare time, under the influence of the Afro-Brazilian Tias Baianas, they were already synthesizing a new music, the Samba carioca…

As in Trinidad with “rival” Calypsonians and in Mexico with musical “duels” between Cantantes de Ranchera, so in Brazil there were Samba compositions in which musicians responded to one another. It was during the 1930s that White Brazilian composers began to absorb the Samba and alter its lyrical content…and gradually the special sound of Rio’s favelas (via Bahia) became the national music of Brazil…We are grateful to Bryan McCann for the following translations of two vintage Samba lyrics from Portuguese into English.

.

Wilson Batista (Black sambista, 1913 – 1968)

“Kerchief around my neck” (1933)

.

My hat tilted to the side

Wood-soled shoe dragging

Kerchief around my neck

Razor in my pocket

I swagger around

I provoke and challenge

I am proud

To be such a vagabond

.

I know they talk

About this conduct of mine

I see those who work

Living in misery

I’m a vagabond

Because I had the inclination

I remember, as a child I wrote samba songs

(Don’t mess with me, I want to see who’s right… )

My hat tilted to the side

Wood-soled shoe dragging

Kerchief around my neck

Razor in my pocket

I swagger around

I provoke and challenge

I am proud

To be such a vagabond

.

And they play

And you sing

And I don’t give in!

. . .

Wilson Batista

“Lenço no pescoço”

.

Meu chapéu do lado

Tamanco arrastando

Lenço no pescoço

Navalha no bolso

Eu passo gingando

Provoco e desafio

Eu tenho orgulho

Em ser tão vadio

.

Sei que eles falam

Deste meu proceder

Eu vejo quem trabalha

Andar no miserê

Eu sou vadio

Porque tive inclinação

Eu me lembro, era criança

Tirava samba-canção

(Comigo não, eu quero ver quem tem razão…)

.

E eles tocam

E você canta

E eu não dou!

. . .

A response-Samba to Batista’s…

Noel Rosa (White sambista, 1910 – 1937)

“Idle Youth” (1933)

.

Stop dragging your wood-soled shoe

Because a wood-soled shoe was never a sandal

Take that kerchief off your neck

Buy dress shoes and a tie

Throw out that razor

It just gets in your way

With your hat cocked, you slipped up

I want you to escape from the police

Making a samba-song

I already gave you paper and a pencil

“Arrange” a love and a guitar

Malandro is a defeatist word

What it does is take away

All the value of sambistas

I propose, to the civilized people,

To call you not a malandro

But rather an idle youth.

.

Malandro in Brazil meant: rogue, scoundrel, street-wise swindler

. . .

Noel Rosa

“Rapaz folgado”

Deixa de arrastar o teu tamanco

Pois tamanco nunca foi sandália

E tira do pescoço o lenço branco

Compra sapato e gravata

Joga fora esta navalha que te atrapalha

Com chapéu do lado deste rata

Da polícia quero que escapes

Fazendo um samba-canção

Já te dei papel e lápis

Arranja um amor e um violão

Malandro é palavra derrotista

Que só serve pra tirar

Todo o valor do sambista

Proponho ao povo civilizado

Não te chamar de malandro

E sim de rapaz folgado.

ZP_Irmandade da Boa Morte_Sisterhood of the Good Death_women devotees of Candomblé in contemporary Bahia_photo by Jill Ann Siegel

For those who observe Lent…just a reminder: next week, February 13th, is Ash Wednesday.

–But up until then … … !

And so, tonight, Friday February 8th, the mayor of Rio will hand over “the keys to the city” to Rei Momo, King Momo (from the Greek Momus – the god of satire and mockery) a.k.a. The Lord of Misrule and Revelry. A symbolic act signifying that the largest party in the world is about to begin. Enjoy!

. . . . .

“Mind is your only ruler – sovereign”: Marcus Garvey and Bob Marley: “Emancípense de la esclavitud mental; nadie más que nosotros puede liberar nuestras mentes.”

Posted: February 6, 2013 Filed under: Bob Marley, Emancípense de la esclavitud mental: Marcus Garvey + Bob Marley y su Canción de Redención, English, Spanish | Tags: Black History Month poems Comments Off on “Mind is your only ruler – sovereign”: Marcus Garvey and Bob Marley: “Emancípense de la esclavitud mental; nadie más que nosotros puede liberar nuestras mentes.”

ZP_Marcus Garvey, 1887 – 1940_Jamaican orator, Black Nationalist and promoter of Pan-Africanism in the Diaspora

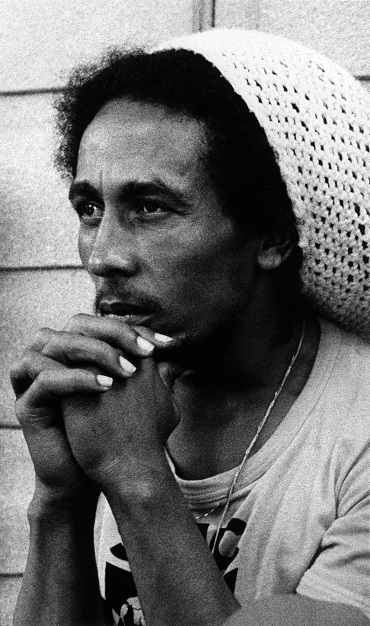

“Redemption Song”, from Bob Marley and The Wailers final studio album (1980), was unlike anything Marley had recorded previously. There is no reggae in in it, rather it is a kind of folksong / spiritual and just him singing with an acoustic guitar. The exhortation to “emancipate yourselves from mental slavery, none but ourselves can free our minds” was taken directly from a famous speech that fellow Jamaican and Pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey gave in Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1937. Garvey published the speech in his Black Man magazine. He had said: “We are going to emancipate ourselves from mental slavery because whilst others might free the body, none but ourselves can free the mind. Mind is your only ruler, sovereign. The man who is not able to develop and use his mind is bound to be the slave of the other man who uses his mind…” Bob Marley was born on this day, February 6th, in 1945. He developed cancer in 1977 but for three years did not seek treatment because of his Rastafarian beliefs; was the illness perhaps Jah’s will? He died in 1981, at the age of 36.

At Marley’s funeral Jamaican Prime Minister Edward Seaga eulogized him thus: “His voice was an omnipresent cry in our electronic world. His sharp features, majestic looks, and prancing style a vivid etching on the landscape of our minds. Bob Marley was never seen. He was “an experience” – which left an indelible imprint with each encounter. Such a man cannot be erased from the mind. He is part of the collective consciousness of the nation.”

.

Robert Nesta ‘Bob’ Marley

“Redemption Song”

.