Rita Bouvier: Nakamowin’sa kahkiyaw ay’sînôwak kici / Wordsongs for all human beings

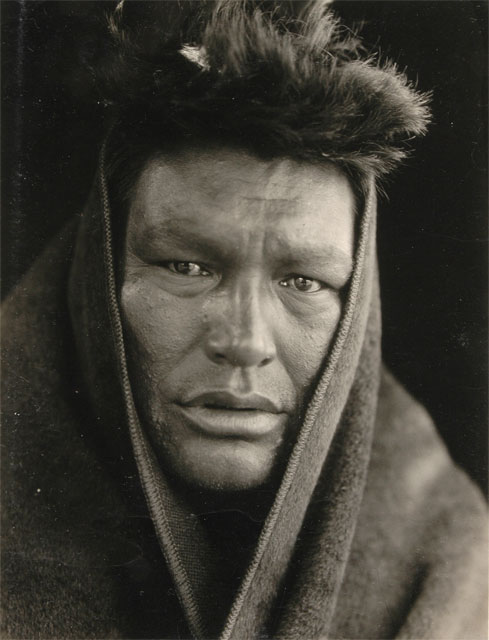

Posted: June 1, 2013 Filed under: Cree, English, Rita Bouvier Comments Off on Rita Bouvier: Nakamowin’sa kahkiyaw ay’sînôwak kici / Wordsongs for all human beings Gabriel Dumont, Métis Leader, photographed by Orlando Scott Goff, around 1886-1888

Gabriel Dumont, Métis Leader, photographed by Orlando Scott Goff, around 1886-1888

.

Rita Bouvier ( Île-à-la-Crosse (Sakittawak), Saskatchewan )

that was a long time ago, and here we are today

.

that was a long time ago

and here we are today

.

listen, listen

the heart of the land beats

.

our children curious

as all children are

will ask the right questions

.

why does a nation take up arms

in a battle knowing it will lose?

knowing it will lose

.

listen, listen

the heart of the land beats

.

when the long night turns to day

remember, hope is the morning

a songbird’s prayer

. . .

I am created

(for my father, Emile)

.

I am created by a natural bond

between a man and a woman,

but this one, is forever two.

one is white, the Other, red.

a polarity of being, absorbed

as one. I am nature with clarity.

.

against my body, white rejects red

and red rejects white. instinctively,

I have learned to love – I have learned to live

though the politics of polarity

is never far away. still, I am

waiting, waiting.

. . .

a spider tale

.

behind the shed

in the tall yellow grass

a cardboard box

is my make-believe home

no one can see me

but I can see

all

their comings

and goings

my auntie Albertine

is washing clothes today

and needs the power

of my long arms

and lanky legs

to haul pails and pails

of water from the lake

.

I watch

as she searches for me

mumbles something about

kihtimigan – that lazy one

walks back inside the house

and out again

calling my name

.

when I appear

out of nowhere

she looks relieved to see me

“nitânis, tânitê oma î kîtotîyin?”

“my daughter, where in the world have you been?”

I tell her –

I was here all along

.

what I don’t tell her is

that I have been spinning tales

trying to understand

the possibility of…

myself as a spider

all legs

travelling here and there

with disturbing speed

my preoccupation with food

my home a web

so intricate and fragile

yet strong as sinew

.

today I remembered

not as sure footed

as I would like to be

someone calling my name

I lost my footing

falling, falling

. . .

we say we want it all

.

we fight amongst ourselves

jealous, one of us is standing.

.

there are no celebrations

for brave deeds among the chaos, instead

.

we joing the banner call for rights

forgetting an idea from the past –

.

responsibility. we join the march

for freedom, forgetting an idea

.

from the past – peace keeping.

we say we want, want it all

.

a piece of the action we know destroys

our home – our relations with each other

.

we are mired so deep, drowning

in our own thinking, thinking

.

we too could have it all, if only…

if only we could see ourselves

Louis Riel’s two children, Jean-Louis and Angélique, ages 6 and 5, photographed at Steele and Wings studio in Winnipeg, 1888

Louis Riel’s two children, Jean-Louis and Angélique, ages 6 and 5, photographed at Steele and Wings studio in Winnipeg, 1888

.

Riel is dead, and I am alive

.

I listen passively while strangers

claim monopoly of the truth.

one claims Riel is hero

while the other insists Riel was mad.

.

I can feel a tension rising, a sterile talk

presenting the life of a living people,

sometime in eighteen eighty five.

now, some time in nineteen ninety five

.

a celebration of some odd sort.

I want to scream. listen you idiots,

Riel is dead! and I am alive!

instead, I sit there mute and voiceless.

.

the truth unravelling, as academics

parade their lines, and cultural imperialists

wave their flags. this time the gatling gun

is academic discourse, followed

.

by a weak response of political rhetoric.

all mumbo-jumbo for a past that is

irreconcilable. this much I know

when I remember – I remember

.

my mother – her hands tender, to touch

my grandmother – her eyes, blue, the sky

my great grandmother – a story, a star gazer

who could read plants, animals and the sky.

. . .

that’s three for you

.

a young man came to me one day wanting

to understand me – the distance between

separate worlds, his and mine, his and mine.

surely, he begged, we could forsake the past

for the future, yours and mine, yours and mine.

.

I listened intently trying to find

the right words to say, to reassure him

my intentions, telling my story – the same.

I told him perhaps the past remembered

holds our future, yours and mine, yours and mine.

.

I wish it was easy to forget

as it is writing this poem for you.

I wish I could believe, I wish we could

break this damn cycle of separate worlds.

I wish I wish I wish. that’s three for you.

. . .

last night at Lydia’s

.

Celtic toe-tapping fiddle

Red River jigging rhythm

runs in my veins

a surge like lightning

.

that testosterone

in the mix tonight.

ohhhh, it feels good

to be alive

.

plaid shirted, tight blue jeans

good-looking, knows it kind-a-man

you hurt my eyes

.

pony-tailed, dark skinned

women in arm kind-a-man

your hurt my eyes

.

rugged, canoe-paddling

handsome kind-a-man

you hurt my eyes

.

muscle busting, v-necked

silver buckled kind-a-man

you hurt my eyes

.

cool leathered, scotch-sipping

drinking kind-a-man

you hurt my eyes

.

quiet wire-rimmed

spectacled kind-a-man

you hurt my eyes

.

you – you – you –

holding my hand kind-a-man

ohhhh, you hurt my eyes

Shane Yellowbird_Cree country-music singer from Alberta

Shane Yellowbird_Cree country-music singer from Alberta

.

hand on hand

.

we made a pact but you were only three.

I was so much older I should have known

better. I promised then to take care of you

as long as my hands were bigger than yours.

.

in return, you promised to take care of

me, when your hands would grow bigger than mine.

today, you came to me wanting to measure

your hand against mine; I said, go away

.

your hands growing way, way too fast for me.

just then, a thick fog descended across

the street. you ran into it curious

unafraid, unaware you were disappearing

.

with every step you took. I ran after you

trying as best as I could to hold on

with you in sight, letting go at each step.

hand on hand we made a pact, you were three.

. . .

wordsongs of a warrior

.

what is poetry? how do I explain

this affliction to my mother

in the language she understands,

words strung together, woven

pieces of memory, naming

and telling the truth in a way

that dances, swings and sways

.

why the subject of my poetry

is sometimes difficult to deliver

why my subjects are terrorized

even controversial, why

the subjects are the essence

of my own being – close to the bone.

.

nakamowin’sa wordsongs

kahkiyaw ay’sînôwak kici for all human beings

ta sohkihtama kipimâsonaw to give strength on this journey

kitahtawî ayis êkwa one of these days, for sure now

kam’skâtonanaw we will find each other

. . .

when the silence breaks

.

I am a reluctant speaker

violence not just a physical thing.

.

words are one thing

I can hold them in my hand

later embroider them

like you do fine silk

on white deer hide

if I want.

but dead silence

that’s another matter

there is nothing to hold on to

like the falling

before you awaken.

.

I imagine it this way, simply

kitahtawî êkwa

one of these days now

when the silence breaks

the deer will stop in their tracks

pausing eyes wide

the wolverine will roll over and over

on the hillside, and

you will hear my voice

as if for the first time

distant and then melodic

and you will recognize it

as your very own.

kitahtawî êkwa

. . .

a ritual for goodbye

(in memory of Albertine)

.

walking the shoreline

this crisp spring morning

in our matching

red-line rubber boots

my cousin and I

are reminiscing

the days gone by

.

I remember first

one early spring

the water so low

we could get

from one island

to the next

our clothes piled high

over our heads

.

she remembers then

no human debris

like there is now

just the odd

piece of driftwood

she reminded me

we wondered then

where it came from

a guessing game

.

walking the shoreline

this crisp spring morning

our walk is certain

clinging close

to what we know best

this shoreline, this bond,

we don’t speak of the fact

that our aunt is dying

. . .

earthly matters

.

when I came to your grave site

late last fall, a chill in the air,

I was feeling sorry for myself.

I came looking for a sign

one might say it was –

guidance on earthly matters.

.

lifting my face skyward

I found nothing but blue sky.

I searched the horizon,

it was then I discovered

a la Bouleau in the distance.

I smiled, recalling

that walk we took

through the new cemetery

on a break from city life.

you didn’t want to be buried

near the saints anyway,

roped in, in a chain-link fence.

you were pointing out,

as if it were a daily business

family plots here and there.

best of all, you claimed

you had selected the ideal plot

for yourself and your family,

a la Bouleau in the distance.

. . .

All poems © Rita Bouvier – from her Thistledown Press collection entitled Papîyâhtak. In the Cree language Papîyâhtak means: to act in a thoughtful way, a respectful way, a joyful way, a balanced way.

.

Rita Bouvier is a journeyer who searches along the way. Her poems are unafraid to take chances; they are complex in emotion, unsparing in intellect. Papîyâhtak includes a number of poems written for actors in The Batoche Musical which was conceived and developed by a theatre and writers’ collective and performed at Back to Batoche Days in Batoche, Saskatchewan. The poem That was a long time ago, and we are here today was inspired by an essay written by South African anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko.

. . .

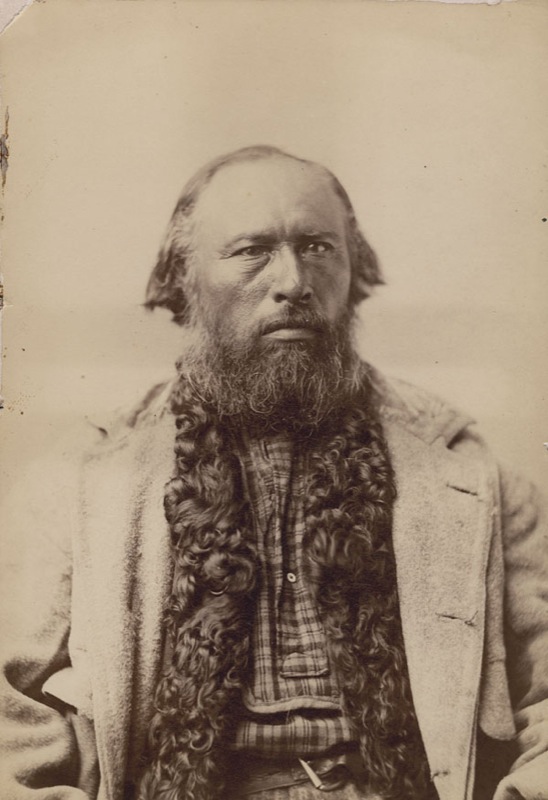

Gabriel Dumont (1837 – 1906) was a leader of the Métis people in what is now the province of Saskatchewan. It was Dumont who brought the exiled Louis Riel (1844 – 1885) back to Canada to pressure Canadian authorities to recognize the Métis as a Nation. Sharpshooter with a rifle, Dumont was Riel’s chief right-hand man and he led the Métis forces in the North-West Resistance (or Rebellion – as Ottawa-centric history books described it) of 1885.

Louis Riel was one of the towering Hero figures of Canadian history. For more on Riel – and a letter/poem he wrote to Sir John A. Macdonald, his ideological opposite – (along with a letter/poem addressed to Macdonald by contemporary Métis poet Marilyn Dumont) – click the following ZP link for January 11th, 2012:

https://zocalopoets.com/category/poets-poetas/marilyn-dumont/

. . . . .

Hydro-Electricity and Eeyou Istchee (The People’s Land): a Cree poet’s perspective

Posted: June 1, 2013 Filed under: English, Margaret Sam-Cromarty Comments Off on Hydro-Electricity and Eeyou Istchee (The People’s Land): a Cree poet’s perspective A segment of the massive James Bay hydroelectric project in Québec_ photograph © David Maisel

A segment of the massive James Bay hydroelectric project in Québec_ photograph © David Maisel

.

Margaret Sam-Cromarty (born 1936, Fort George Island, James Bay, Québec)

“Rivers”

.

Tears are like rivers;

they never stop flowing.

Rivers are like tears;

they become dry.

. . .

“Sphagnum Moss (Baby Moss)”

.

By my door she stood,

an old bag in her hand.

The bag she held

was full of moss from the land.

.

She asked me: Do you need

fresh moss for baby?

Yes, I said,

it keeps the baby dry.

.

She smiled, If you want

I will get more for you.

Knowing her skill,

I nod my head.

.

She goes early to the wet swamps

to find and pick moss

for a little baby.

.

She never wears gloves,

her hands red from cold.

She loves

gathering the soft moss.

.

She chooses a spot

where the sun shines a lot.

The wet cold moss has to dry

before she brings some to me.

.

Over the years I never used

anything so soft and fine

for a baby’s behind

as the moss she brought with a smile.

. . .

“A Cree Child”

.

On the east coast of James Bay

both governments didn’t care.

Other matters were more important

than a Cree child

who sometimes had little to eat.

.

There was no dancing,

no feasting,

in this, the height of the Depression.

The Indians had a passion –

hunting and following

the fur-bearing animals.

.

But the price of furs

was at its lowest.

The Crees did their best

to feed and clothe themselves.

.

In the early days

Crees’ lives

meant the Hudson Bay Company

traders who sometimes denied

Indians credit.

.

The church played a part,

an important role,

saw the suicidal conditions,

decided it best to save souls.

.

I recall small steps

in the cold Northern snow,

a sweet life taken,

a little boy with no shoes.

.

Deeply moved, I weep.

He was my brother.

The now-derelict ferry to Fort George Island just off the Chisasibi Road_near James Bay in Québec

The now-derelict ferry to Fort George Island just off the Chisasibi Road_near James Bay in Québec

.

“Memories of Fort George

and of Alice who lived there until her death”

.

My memories of Fort George

are warm and sad.

Down by the river banks

cooled by gentle breezes

from the open bay

the elders sit on the tall grass

playing checkers all day.

.

Someone shouts, “I see the ship”.

Mr. Duncan, the storekeeper,

is down by the Hudson Bay dock.

Game forgotten, they watch

as John the Native navigator

safely guides the supply ship.

.

Navigation by John and other Crees

was needed by captains.

There were no light beacons

to mark the dangerous

sandbars and rock.

Fort George Island never

joined the mainland.

.

The excitement reached the teepees

surrounding the grounds

of the Hudson Bay store.

Women and children rush to the river,

the smell of smoke in their clothing,

to welcome the supply ship.

.

Another big event –

the long midsummer’s eve service.

The Native catechists

in white robes against the crimson sunset,

the women in bright shawls,

the men in their best clothes,

babies with happy smiles.

.

My memories of a hunt

of the coastal people:

a big seal, a white whale.

Someone shouted, “We share –

bring your pots and pans.”

No money changes hands.

The same sharing if someone

kills a black bear

among the inland people.

.

My fondest memory

is of a lovely lady.

Her baked bannock – so good.

I see her sitting in her smoke teepee,

around her the sweet smell

of many spruce boughs.

. . .

“James Bay”

.

James Bay, my home,

is closer than the moon,

its regions so bare,

aloof and remote.

.

Hudson Bay flows

to James Bay,

both beautiful,

wild and free.

.

The rugged coasts

of James Bay and Hudson Bay,

their charm

meets my eyes.

.

The sights and sounds

of James Bay.

They wrap around me,

giving me peace.

. . .

“Black Island”

.

I love your high cliffs,

your rocky shores,

the sounds of surf

and the shadows of a midsummer’s eve.

.

I love your coves,

the strong winds

causing high tides

and heavy fog.

.

I love the smell of seaweed

on your beaches, and driftwood,

the hot breezes from the south

causing low tides, bringing sinking mud.

.

I love the rumble of thunder

far away,

lightning zig-zags across the sky,

creatures seeking shelter.

.

I love to hear the wild ducks

feeding in the marshes,

the white gulls hovering,

the heat wave shimmering.

.

I love the islands

in James Bay:

Governor’s Island, Fort George Island,

Grassy Island and Ship Island.

. . .

“Steel Towers”

.

One cold day

I stood on the shores of James Bay.

The sun shone bright, the sky blue.

I wanted to find a clue.

.

Why, among the spruce and pine

rows of steel towers stood in line.

They were out of place,

near and Indian camp.

.

Looking for white birds’ tracks,

instead as I turn my back

Tracks of bulldozers meet my sight –

Ruining the landscape in the fading light.

.

Against the sky and beyond

stand stark steel towers.

In this harsh land of ice and snow

these steel towers are colder than forty below.

.

We Cree live in harmony

on this beautiful land.

In a land where no man had trod,

in the fresh snow I read

.

Signs of upheaval of black earth.

Bulldozers making roads

and steel towers standing tall.

. . .

“Promises”

(for the many who committed suicide in Chisasibi)

.

I am alone.

I feel so lost.

I am not in need

of material things.

.

I am confused.

Looking at myself

I abuse

love and understanding.

.

Stay with me, for my sake.

Despair I have.

No one hears

my pleas.

.

We lived in fancy houses –

no more outhouses.

The leaders of my people

made promises and promises.

.

I love to learn,

to assure myself

I have a reason

to save my soul.

.

In shame I suffer.

Nobody to ease my hurt.

I found myself afraid,

the problems too great.

. . .

“Life”

.

In this time

of steel

and of speed,

we need

poetry.

Like a friend

warm and true

shedding a tear.

See it hang,

roll down,

feel things unseen.

Drawn

to things we see,

like the setting sun

of breathtaking colours.

A new dawn:

in its blue-shadow world

things move so fast.

.

Now moving faster and faster.

. . .

Margaret Sam-Cromarty, Cree mother, grandmother, and poet, was among about 5,000 Native people whose villages and hunting lands were flooded as part of the province of Québec’s huge hydro-electricity projects involving many rivers which drain into James Bay (the lower portion of Hudson Bay). Damming, river diversion, the creation of huge reservoirs – all of this has reconfigured the surrounding landscape – submerging vast tracts of Boreal forest (black spruce and bogs, mainly) under water, and making mercury contamination a health issue (fish and drinking water). Caribou migration, waterfowl habitat, salmon spawning – all have been affected adversely. The massive water-energy-harnessing infrastructure building-boom began in 1971 (with the construction of the first permanent road into the “taiga” landscape, the James Bay Road) and continues into 2013. It has included the La Grande Project (which saw the elimination of Sam-Cromarty’s birthplace-island, Fort George Island, as a habitable place – and the relocation of Cree villagers from FGI and neighbouring settlements to the government-planned town of Chisasibi in 1981); and the Great Whale Project – a lightning rod for environmental political activism in the early 1990s – which saw Cree Grand Chief Matthew Coon Come garner favourable publicity as he “canoed” to New York City – from Hudson Bay to the Hudson River – and New York State (the #1 hydroelectric energy client of Hydro-Québec) decided not to sign yet another energy agreement with the province. But North America’s appetite for Energy does not lessen; the Eastmain and Sarcelle generating stations have since been built, and 70% of the Rupert River was diverted in 2009-2010. In this latest phase Québec has signed a cooperation agreement over environmental regulations and impact with the Grand Council of the Crees representing 18,000 Crees living on or near present – and future – Hydro Project lands. One thing is for sure by now, and the poet knows it: You cannot go Home again – only in dreams and poems.

. . . . .

Nous connaissons le secret de la petite épinette / We know the secret of the little spruce: poèmes d’une Aînée Crie / poems of a Cree Elder

Posted: June 1, 2013 Filed under: English, French, Margaret Sam-Cromarty Comments Off on Nous connaissons le secret de la petite épinette / We know the secret of the little spruce: poèmes d’une Aînée Crie / poems of a Cree Elder.

Margaret Sam-Cromarty (née à l’île Fort George, La baie James, Québec, 1936)

“Un étranger très élégant”

.

Un jour, dans un village nordique,

tout le monde se préparait

en vue du départ

pour la chasse printanière.

Vers le début de la soirée,

les enfants en train de jouer ont commencé à crier:

“Nous voyons venir un étranger.

Il est bien habillé.”

.

En effet, l’étranger était saisissant.

Personne ne semblait le connaître.

Les jeunes filles tournaient autour de lui…

les mouches aussi.

.

On l’invita à l’intérieur de la tente.

La chaleur du feu de camp

mit l’étranger mal à l’aise.

Tout le monde se demandait pourquoi.

.

Souriant aux jeunes filles,

il sortit prendre l’air.

Une mauvaise odeur flottait derrière lui

et les mouches lui bourdonnaient tout autour.

.

Les jeunes filles voulaient qu’il reste

mais il est parti comme il était venu.

Bientôt il disparut,

laissant les jeunes filles à leur tristesse.

.

L’une d’entre elles suivit ses traces

qui la menèrent à un tas de fumier.

La chaleur avait fait fondre l’étranger.

Les mouches bourdonnaient et chantaient:

“Merde et vielles guenilles,

merde et vielles guenilles,

s’étaient changées en homme!”

. . .

“The Handsome Stranger”

.

Once in a northern village

people were making ready

to move away

for the spring hunt.

.

Now it was towards evening

when children at play began to shout

“We see a stranger coming.

He is smartly dressed.”

Indeed the stranger was striking.

No one seemed to know him.

The young girls hung around him.

So did the flies.

.

He was invited inside the tent.

The heat from the campfire

made the stranger uncomfortable.

Everyone wondered why.

.

Smiling at the girls

he went outside for the air.

The stranger left a wave of smell

and buzzing flies behind.

.

The young girls wanted him to stay

but he left the way he came.

Soon he disappeared,

leaving the girls sad.

.

One of them followed his tracks

until they led to manure.

He had melted from the heat.

Flies buzzing around sang:

“Shit and old rags,

shit and old rags,

turned himself into a man.”

. . .

“Un garçon”

.

Des cheveux noirs comme du jais

qu’il avait de naissance,

Des yeux noirs

qui brillaient d’un amour chaleureux.

.

De mains fines,

de bonnes mains de musicien.

Ce garçon a découvert

que grandir était douloureux.

.

Il préférait attraper des grenouilles,

taquiner sa soeur,

serrer ses bras

autour de sa mère.

.

Il a grandi,

aussi grand qu’un arbre.

Une personne gentille,

ce garçon qui est le mien!

. . .

“Boy”

.

His jet black hair

he had from birth

His dark eyes

flashed loving warmth

.

His fine shaped hands

right for a musician

This boy who found

Growing up a pain

.

He’d rather catch frogs

tease his sister

Throw his arms

around his mother

.

He has grown

tall as a tree

A gentle person

this boy of mine

. . .

“Une fille”

.

Une fille aux yeux noirs et brillants,

au sourire doux et timide,

à la peau fine cuivrée,

qui n’a pas besoin du soleil d’été.

.

Elle avait

de longs cheveux d’ébène.

Plusieurs étaient d’accord:

elle était belle.

.

C’était le vent.

C’était le ciel.

C’était ma fille…

Mary.

. . .

“Girl”

.

A girl her dark eyes bright

Her smile shy and sweet

Her fine copper skin

needs no summer sun

.

She was blessed

with long raven hair

many agreed

she was fair

.

She was wind

She was sky

She was my daughter

Mary

. . .

“Maman”

.

Une mère

passe à travers

les rejets, les dépressions,

la solitude et les critiques.

.

C’est une femme courageuse

douée d’un humour fin.

Une créature qu’on appelle

Maman.

. . .

“Mother”

.

A mother

goes through

rejections, depressions

.

Loneliness and criticism

.

A courageous woman

with gentle humour,

a creature known as

Mother

. . .

“Maris et Femmes”

.

Le mari est le ciel

et la femme le nuage.

.

Parfois le ciel

apporte le vent

et le nuage une pluie rafraîchissante.

.

Parfois les nuages

se regroupent

et apportent orages et vents.

Maris et femmes font de même.

.

Maris et femmes dérivent séparément

comme les nuages le font parfois.

Mais au milieu de nuages gris,

jaillit le ciel bleu clair.

.

Comme les nuages se rassemblent

pour former le temps,

ainsi font maris et femmes

pour mener leurs vies.

.

Les anneaux autour du soleil

nous rappellent le mauvais temps.

Les anneaux du mari et de la femme

scellent un amour infini.

. . .

“Husbands and Wives”

.

Husband is the sky

a wife the cloud

.

Sometimes the sky

brings wind,

the cloud a refreshing rain

.

Sometimes the clouds

form to gather

It brings storms and winds

Husbands and wives do the same

.

Husbands and wives drift apart

like clouds sometimes do

But between the greyish clouds

burst bright blue skies

.

As the clouds come to gather

to create our weather

So do husbands and wives

carry on with their lives

.

The rings around the sun

remind us of bad weather

The rings of husbands and wives

shield a love forever

. . .

“La gentillesse”

.

La gentillesse, c’est faire cuire de la banic,

mélanger la farine et la levure.

Il faut y mettre de l’eau.

.

Pour faire une bonne banic,

on y ajoute de l’huile.

Dans nos vies,

on a besoin de la gentillesse.

.

La gentillesse est comme les graines.

Beaucoup se perdent.

Pas de graine,

Pas de gentillesse.

. . .

“Kindness”

.

Kindness is baking bannock

blending flour, baking powder

It’s natural to put water

.

A good bannock

oil is added

In our lives

kindness is needed

.

Kindness is like grain

many are lost

without grain

without kindness

. . .

“La Paix”

.

Trouvez la paix dans le silence,

le silence qui règne ici.

Le vent froid

purifie la terre.

.

La splendeur.

Il n’y a pas de terreur.

Des tiges de plantes séchées se tiennent

bien droites.

.

Écoutez le vent impétueux.

Regardez les sentiers blancs, les grands cercles,

la rivière tranquille,

le ciel, bon et puissant.

. . .

“Peace”

.

Find peace in silence

Silence it reigns here

The cold wind

Purifies the land

.

The splendour

There is no terror

Stalks of dried plants stand

upright

.

Hear the rushing wind

See the white paths, the wide circles

A quiet river,

the sky, bold and good.

. . . . .

Quelques pensées de la poétesse:

Mon père et ma mère étaient des Cris. Ils vivaient à la baie James. C’est là que je suis née, dans le village de l’île Fort George, où la rivière La Grande se jette dans la baie James. J’ai appris à parler et à écrire l’anglais. Les Cris sont des chasseurs et des trappeurs…Nous comprenons les animaux et les oiseaux…Nous connaissons le secret de la petite épinette…Et nous écoutons nos frères et soeurs comme nos Aînés nous l’ont enseigné… (Maintenant) nous vivons à Chisasibi… Et c’est aussi là que grandissent nos petits-enfants… Dans ma mémoire vibre encore le village de Fort George, un village qui n’a pas été inondé ni abandonné et qui est plein de Cris joyeux. C’est de cette façon que je veux me rappeler l’île de Fort George…

Some thoughts from the poet:

My father and mother were Cree. Their home was James Bay in Northern Québec. This is where I was born, at a Cree village of Fort George Island, where the La Grande River empties into James Bay. I was taught to speak and write English. My people, the Crees, are hunters and trappers… We understand the animals and birds… We know the secret of the little spruce… And we hear our brothers and sisters the way our Elders taught us… (We) now live in a town called Chisasibi… Our grandchildren are growing up in Chisasibi… In my memory stands a Cree village of Fort George not flooded or abandoned but full of happy Crees… It’s the way I would like to remember Fort George Island…

.

Editor’s note: Chisasibi or ᒋᓴᓯᐱ in Cree syllabics (meaning Great River) is a town created by the Québec government to relocate Crees who were forced from their James Bay watershed lands (including Fort George Island) because of damming/redirecting of tributary rivers flowing into the La Grande River as part of Hydro-Québec’s James Bay Project which began in the 1970s and continues into the present day.

. . . . .

“Nêhiyâwin” / “The Cree Way” – as told by Harry Blackbird

Posted: June 1, 2013 Filed under: Cree, English, Harry Blackbird Comments Off on “Nêhiyâwin” / “The Cree Way” – as told by Harry BlackbirdCree Elder Harry Blackbird

(born in the 1920s at Waterhen Lake First Nation,

roots in Makwa Sahgaiehcan (Loon Lake) First Nation, Saskatchewan, Canada)

“Nêhiyâwin”

.

Pêyakwâw êsa mîna ê-nanipât awa pêyak kisîyiniw, kâ-pawâtât onôtokwêma ê-pê-kiyokâkot. nikotwâsik askîy aspin ê-kî-nakataskîyit. êkwa ôma êkwa otahcahkwa kâ- pê-kiyokêyit. mitoni pîkwêyihtam êsa awa kisiyiniw, êkwa ôma ê-kamwâcipayit, ê- simatapit. nohtê-kiskêyihtam ôma, tânêhki kâ-pê-itohtêyit.

.

Mâci-pîkiskwêyiwa êsa ê-itikot, “ê-pê-itisahot ôma Mâmawi-ohtâwîmâw ta-pê- wihtamâtân kîkway. ana ohci oskinikîs kâ-kî-nakataskît ôta namôya kayâs.

.

Ispî kâ-takohtêt ôtê ahcahk-askîhk, pê-nakiskâk oskâpêwisa ê-kiskinohtahikot ê- wêhcasiniyik mêskanaw. pêyakwâyak anita, nîswâyak paski-môniyâw ôma mêskanaw nistam anima kihciniskêhk k-êsi-paskêmok mêskanaw, êyako pimitisahamwak. êyako mîna mitoni miywâsin ta-pimitisahamihk. piyisk kêtahtawê k-ôtihtahkik ita ê-ayâwiht tâskôc ê-wâ-wîkihk. sêmâk ôhi wîci-oskâya pêyakwan ê-ispihcisiyit, kâ-pê-nakiskâkot, êkoni ôhi osk-âya mêtoni nanâkatohkâtik.

.

Kâ-mâci-pîkiskwâtikot ôhi oskâya ê-nêhiyawêyit. mâka namôya nisitohtawêw awa oskinikîs tânisi ê-itwêyit âta wîsta ê-nêhiyawêt. ahpô mîna apihkêw tâskôc mâna ôki nêhiyawak mitoni kâ-pimitisahakik onêhiyâwininiwâw. pîkwêyihtam ê-wanihkêt awa oskinîkîs. âsamîna sipwêhtahik oskâpêwisa kotak êkwa anima mêskanaw ita kâ-kî- ohtohtêcik.

.

Êyako mîna ôma mêskanaw miywâsin êkwa wêhcasin ta-pimitisahamihk. otihtamwak wâskahikana ita câh-cîki ê-wâh-wîkihk. âsamîna êkota kotaka osk-âya pê- nakiskâk mâka êkwa ôki oskâyak namôya cîki pê-nâtik, wâhyawês ohci osâpamik, ê- pômênâkosicik ê-kanawâpamâcik ôhi oskinîkîsa ê-nêhiyâwinâkosiyit. nanitohtawêw ê- kîmôci-pîkiskwêyit. âtiht piko kîkway kâh-kahcicihtam. êkoni êkwa nisitohtawêw oskâya osâm piko ê-âkayâsîmocik, mâka namôya tâpwê cîkêyimik k-îsi-waskawîyit. mâmisihow, ê-pa-pêyakot ê-nitaw-mâmitonêyihtahk tânêhki êkâ nânitaw kâ-kî-wîcihiwêt.

.

Âsamîna êkota ohci sipwêhtahik oskâpêwisa awa oskinîkîs, mâka êkwa êkotê nakatik ita kâ-nîso-paskêmoniyiki mêskanawa, otahcahkwa ê-wanisiniyit mîna ê- papâmâcihoyit êkotê nâyiwâc osâm êkâ ê-ohci-kiskinohamâsot mîna êkâ ohci- wawîyêstahk onêhiyâwiwin mêkwâc ôta askîhk ê-pimâtisit.”

.

“Hâw, kisêyiniw”, itwêw awa nôtokwêw, “otahcahkwa pwâmayî-sipwêhtêt kâwi kiya êkwa piko ta-wihtamawacik, mîna t-âcimostawacik osk-âyak ôma âcimowin k-ôh-pê- itisahokawiyân ta-pê-wihtamâtân.”

“The Cree Way”: a teaching story told by Cree Elder Harry Blackbird

Translation into English by Mary Anne Martell

.

One day while sleeping, an elderly man was awakened by his deceased wife of six years. She came in spirit form. The elderly man had mixed feelings about this visit but nevertheless managed to remain calm and sat up curious wondering why she had come to visit him.

.

She began to speak, “Listen very carefully… I have been sent by the Creator to tell you about a boy who passed away recently.

.

Upon entering the spirit world he was greeted by an Oskapêwis (Helper) who led the young man down an easy road to follow. At a certain point the road forked going in two directions. They first traveled down the road to the right. This road was also easy to follow. After walking for some time they came to a village. A number of young people about the same age as the youth came running towards him. The group of young people stopped to observe the new boy who’d been brought to them by the Oskapêwis.

.

The young people then began to speak in the language of his ancestry – Nêhiyawêwin (the Cree language). Unfortunately the young man could not make out what they were saying even though he was of the same nation; Nêhiyaw. He even had the two long braids of hair, common trademarks for Nêhiyawak who were following the Nêhiyawin (Cree worldview) way. Confused and feeling lost, the young man was quickly whisked away by the Oskapêwis towards the other road at the fork.

.

This new road was also easy to follow. They came upon a cluster of houses and another group of young people came towards him. Only this time these youth kept their distance with disappointment written all over their faces upon viewing his Aboriginal features. Listening to their conversation as they whispered among themselves, the young man could only make out a few words. He was able to understand these youth because they spoke English, but they obviously weren’t interested in this new boy by their behaviour. He felt betrayed, alone and wondered why he didn’t fit in.

.

The Oskapêwis once again whisked him away and this time left the young man at the fork of the road. His spirit is lost and wandering now because while alive he hadn’t learned to find his way.”

.

“Now, my husband,” the deceased wife’s spirit added just before she vanished, “it is up to you to make certain that young Indian children are told this story I have been sent here to tell you.”

. . . . .

Top photograph: Napéu (Man)_Cree_1926 photograph by Edward Curtis

Middle photograph: Louis Nomee, Kalispel, Montana_photograph by Richard T. Lewis_1940s

Bottom photograph: An Elder congratulates a boy upon his completion of Grade 6 at an Awasis Day event in Edmonton, Alberta_June 2005.

Mosha Folger: “Leaving my Cold Self behind”

Posted: April 29, 2013 Filed under: English, Mosha Folger Comments Off on Mosha Folger: “Leaving my Cold Self behind”Mosha Folger

“Ancient Patience”

.

If you look back to the North

A couple of thousand years ago

To where the Atlantic ice fields

Battle the granite shield of the Arctic coast

You’d find a man staking claim to a land

That just doesn’t seem inhabitable

an Eskimo

a patient hunter who stood unmoving for hours

crouched over small bumps in the ice

subtle seal-breathing holes

Wicked winds pushing the temperature back down

from the comfort of twenty below

Facing the low sun so his shadow fell back

away from his goal

Waiting for a freezing breathe-out

to break the crystal white flatness of snow

.

Arm cocked, harpoon ready

eyes unblinking, blazing their own little holes

in the ice floe

Mouth closed, breath low

Because less movement, less sound

meant the night’s dinner was more likely to show

Yet sometimes that hunter

stood till the moon rose

before he finally shifted, breathed hard

and set off for home with nothing but cold toes

Nothing to bloody his wife’s arms to the elbows

Nothing to warm the guts of five kids

or silence the dogs’ moans

.

Nothing but the knowledge that

the next day when he woke

to stand again over that hole

maybe, just maybe

a seal would finally show him his nose

so the harpoon could come down

to deliver its lethal blow

Or maybe, just maybe

no

.

It’s that patience that allowed my people

to settle down and call the Arctic

our home.

. . .

“Summer Play”

.

In the Arctic desert where

the earth is sand and rocks

and the lichen cling

to the frayed edges of life

in granite fields

and the wet season feels like

three days of monsoon rains

.

In that place

patches of pavement

to a kid are

hallowed grounds

where devout children

offer their time

as sacrifice

with an endless circling of bikes

and an incessant bouncing of balls

like the pounding

and kneading

of rubber into cement

could stretch out

that holy land

.

How wondrous that

a tiny square of earth

can be home to so many

boundless dreams

.

But the reality is mostly

the sand and rocks

and gravel roads, and so

the games played adapt

games of writing

or drawing in the sand

and for one reason or another

chasing each other around

.

A television drawn in the dirt

with movies and shows

initialed inside

to be guessed at

D dot P dot S dot and

if someone gets it right

a frantic chase ensues

Or I Declare War

with a giant circle divided

into America and the USSR

Canada and sometimes Uganda

where the war of course

is chasing

and the fastest world leader

had dominion over all Man

.

And on the longest nights of daylight

baseball

Inuktitut style where groggy kids

up two days under constant sun

and stumbling

play with a rubber ball

by rules that themselves

are drowsy from the endless light

so the outfield

spans the whole town

making foul balls

as fair as any other

and the bases are run wrongwise

and whacking a runner

with the ball

is an out

.

Which means of course

the rest of the game is secondary

to learning how to throw

to anticipate

to picking off the right kid

in the right spot

every time

.

And so when a parent

with a voice that too

spans the whole town

finally calls in

one too many Expos

the real winners

aren’t on the team

with the most runs

but the team that

on the quick walk home

brags about the best

outs.

. . .

“Where have all the Shaman gone?”

.

In the blink of an eye

we’ve gone from a culture where

shaman conjured spirits and

swam, fed and bred

with giant Bowhead whales

for months at a time

And people held out hope that

sometime in their life

they’d be lucky enough to witness

that rare instance

of a distant-Inuit visit

Where men from another planet descended

to collect caches of rich seal fat

overloading their space-sleds

before packing up to head back

But blink

and we wake to a world where

all of that’s been reclassified filed and stacked

under the wild imaginations of

savage heathens

still unclean

cause they hadn’t discovered their

one true saviour and

path to heaven yet

Now elected Nunavut officials can be found

in a big hall amongst a big crowd

falling face down

wailing at the top of their lungs

praising Jesus’s name

and speaking in tongues

The holy spirit come upon their earthly vessel

leaving them convulsing

Spastic believers

shaking under the giant blue and white

Israeli flag they’ve hung

.

Inuit in the day

must have been some of the easiest

lost souls to convert

A hard frozen life of

struggle pain and loss made more palatable

with the promise of a kind of

spiritual dessert

Swallow the death cold and starvation down here

and when you die

enjoy the warm salvation up there

And some of those Arctic locals

fell hard for those lies

Or promises I guess you would call them

if you fell on the other side of the line

But it couldn’t have been made easy

or simplistic could it? No,

First the Anglicans and Catholics

split villages and

pit kin against kin

Families feuding over which clan

would really get to go

And which side

picked the wrong guy’s

rules to abide by

They’ve gotten over it now though

living in a kind harmony

that the rest of what we call

civilized society

should get to know

.

But now in the Arctic we have these

evangelical proselytizing types

whose fervour makes the Anglican and Catholic devotion

seem downright secular cause

they’ve got no HYPE

No souls being sucked

from bodies to on high

No chanting and dancing

with arms to the sky

No religious stakes in the continuation

of the state of Palestine

No possession

The craziest thing they’ve got

is a little blood into wine

Maybe a little shaman incantation

would do those folks some good

Could we at least get them a little reading

from the Koran or Talmud?

That’s unlikely though

Their faith blinds them so deep

The Good News Bible’s the only text

their eyes can see

We’ll have to get a closet shaman

to do a little midnight chanting

see if we can’t set some of those zealots free.

. . .

“Leaving my Cold Self behind”

.

Now there will be no more falling down

unique crunching packing sound

or children who know no other way to live winter

than to tumble sideways and upside-down

from snow banks ten feet off the ground

There will be no snow wind-blown

from parts unknown to all

but the most trained hunters

who brave the vast white fields alone

There will be no high-pitched wailing moan

of snowmobiles flying down

snow-packed gravel roads

No riders with grins plastered

Reveling in their temporary freedom from

small-town poor-me isolation syndrome

There will be no husky howls to wake me

to call me to their battle with the wind

the wind that howls back in kind

and relentless remorseless never fails to win

There will be no more dancing northern lights

chased from their nightly show

by southern skyline stage-fright

There will be only the warm glow

of a cold city that states its case

with what it sees as some divine right

to throw its gaudy remnants

high and loud into the night

There will be only nights where time is slowed

No sleep no comfort no peace

only this page this pen my words

and my message that

no matter the price sometimes

you just have to come in out of the cold.

. . .

“Old Indifferences”

.

Inuit existence was dependent partly on every member

of the encampment being able to at the very least get up

on their own two feet walk across the jagged tundra to follow

the moving caribou so everyone could eat

.

So we adopted an effective means of excising inefficient limbs

from the family tree that left the aged floating on ice pans and

insolent sons turned away to find their own path through

the cruel Arctic days

.

This isn’t a tradition we should reprise as it slides snugly into

its place in the still mostly unwritten Inuit histories but

it has a related convention that’s made its way down into

unofficial modern Inuit custom

.

If you’ve walked downtown Montreal you’ve seen it and in Ottawa

the spring thaw brings about the re-emergence in earnest of the

panhandling Eskimos downtown between the Mall and King Edward

on Rideau Street

.

Whether these people are a nuisance isn’t a question to me because

I have to ask if these people are friends or family maybe a second cousin

and do I have to follow protocol stop and ask a few

inconsequential questions

.

I try to avoid having to do that by changing up my Inuk stride

and remembering that from a distance I could look Thai

but Inuit could never fully ostracize so when I meet one

I stop say hi and try to be polite

.

I ask about my friend their son despite the likelihood that I

was the last to see their child and it hurts inside when they

ask and I have to tell them I hadn’t seen their kid in a little while but that

I knew he wasn’t going to trial

.

It requires a certain distance to sit back and witness these lives with blood

that courses from the same point as mine float away on slabs of concrete ice

but disease strikes and existence has always insisted

on a little bit of indifference.

.

All poems © Mosha Folger

. . .

Mosha Folger (aka M.O.) was born in Frobisher Bay, North-West Territories (now called Iqaluit, Nunavut) to an Inuk mother and American father. A poet, writer, performer, and “Eskimocentric” spoken-word/hiphop rhymer, Mosha has taken part in the Weesageechak Begins to Dance festival, also at WestFest in Ottawa, the Railway Club in Vancouver, and the Great Northern Arts Festival in Inuvik (where he was chosen a Best New Artist). His video, Never Saw It (2008), combined breakdancing with traditional Inupiat dancing, and was an official selection at the Winnipeg Aboriginal Film Festival. His very-personal film, Anaana, examined the effects of residential school (upon his mother). His hiphop song Muscox (2009), with Kinnie Starr, includes lyrics that refer to the suicide of a young friend: “I couldn’t be there when they buried my boy Taitusi … epitome of a boy who should grow into an Inuk man … artistic and witty … too smart for his own good God DAMN, too smart to live shitty … … Not knowing when he died / part of the rest of us went with him.” In North America circa 1491 (2011) – from his album String Games (with Geothermal M.C.) – he says he’ll “show you how far back in time you can date my rhyme … I’m a native son but I speak a foreign tongue – this is North America circa 1491.” And: “I’m out to win this – but the prize isn’t for the witless.”

Hiphop as self-expression for Inuit youth of the next generation younger than Folger is bursting into being, and performers such as Hannah Tooktoo of Nunavik (Northern Québec) effortlessly combine it with the unique “throat singing” of older generations of Inuk.

Mosha has been an active poetry performer in Ottawa, also a member of the Bill Brown 1-2-3 Slam collective. At Tungasuvvingat Inuit and at the Ottawa Inuit Children’s Centre he has brought the power and the fun of spoken-word and hiphop to teens and children.

. . . . .

“Yeah Bro, I should say we do have Eskimo Lies”: the poetry of Inuit writer Norma Dunning

Posted: April 25, 2013 Filed under: English, Inuktitut, Norma Dunning Comments Off on “Yeah Bro, I should say we do have Eskimo Lies”: the poetry of Inuit writer Norma Dunning.

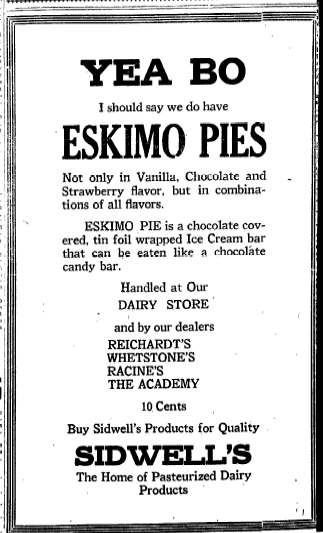

Eskimo Pie I

.

Found on Wikipedia under “Eskimo Pie”:

.

My response to the ad:

.

YEAH BRO

I should say we do have

ESKIMO LIES

Not only in N. Canada and

Urban centers, but in

combina-

tions of all flavors.

Eskimo Lies is a

sugercoated

conception of Northern

Peoples

Handled at Our

GOVERNMENT OFFICES

and by our general public

LIBERALS, PCs, RCMP

& THE

ACADEMY

NO SENSE

Buy Eskimo Lies – A Quality

Product of Canada

The Home of PASTEURIZED

Inuit History

.

Eskimo Pie II

Oh give me a piece of that Eskimo Pie.

.

16 crushed chocolate wafers

4 tbsp of melted butter

.

An entire grouping of humanity

Secured in residential school, left to die

Let me see that chubby little brown face

Filled with 32 marshmallows

.

1/2 cup milk

1/8 tsp m.s.g.

Smiling inside a padlocked fur-ringed space

Include 1 tbsp of vanilla and

1 cup of heavy cream – whipped,

Beat the little heathens

Put them in their place

Melt the marshmallows,

Along with their mother tongues

Whiten with milk,

.

Add the salt

To the wounds

.

And vanilla in a double-boiler

Turn the heat on high

Bring to a boil

Simmer and strain

Removing all their relatives

Cool the filling

Fold in the whipped cream

Pour into a pie plate

.

Slice and Assimilate

.

To the Eskimos of Canada

.

We came here to make them better

Teaching them church and knitting sweaters

.

Changed their names and made them right

These dirty little animals full of fight

.

Taught them how to wash their hands

Took them off their hostile lands

.

Bringing them to our enlightened age

Gave them names on a page

.

They’re happier than they’ve ever been

A better side of life they have finally seen

.

Our mission is soon complete

They will no longer eat raw meat

.

We’ll soldier on in our god’s name

These lowly people we will tame

.

They will thank us for this soon one day

And on their land we will forever stay

.

The Necklace

(Or Forms of 20th Century Shackling – The Eskimo Identification Canada System 1941-1978)

I gave you a necklace made out of sting

Such a pretty thing, such a pretty thing

I told you to wear forever and always

Such a pretty thing, such a pretty thing

I had a number put on it

Just for me!

I told you to remember it always

I did oh I did and oh I still do!

I said it was better than your name

It is oh it is and oh it still is!

If you didn’t have it I won’t be yours

Oh please, no threats, I’m yours always

Without it there would be no happy ever after

Oh please, no threats, no threats

PLEASE!

I told you to write it on all pieces of paper

I will and I have and I must and I do!

If it gets lost – we’re over!

I won’t and I haven’t and I must say I do!

This necklace is the best thing that’s ever

Happened to you

I seem to be lacking air or is

it hair or do I

dare say,

“I’m turning blue”?

.

Kudlik/Qulliq

by

(Norma – in Inuktitut)

.

There is more to this lamp than the lighting

of it. Shared in its shadows are laughter,

crying and the tears of so long ago.

The tears of a sickness changing us for

ever. Echoes of tuberculosis.

Once we were well and we gathered manniq. (wick of moss)

We slept in peace under spring stars hearing

Our giggles and sighs mixed only with the

sounds of the earth. Disease took us from

home and away, far away to stay locked

in the prison of white walls. To cough up

blood of my puvak and long for home. (lung)

No more the qulliq to warm our spirits (stone lamp)

Warm our hearts, heat our lives, feed our stomachs.

Our revolution came in Quallnaat

Bacteria and the light of the

qulliq grew dim. Black wisps answered our cries

blowing out the wick of what we once were.

.

For Mini Aodla-Freeman, the last living Inuit woman in Canada who knows the traditional uses of the Qulliq. She is the last keeper of this traditional Inuit flame.

. . . . .

In the poet’s words:

My name is Norma Dunning. I am a Beneficiary of Nunavut and a first-year M.A. Student at the University of Alberta with the inaugural class of M.A. Students in the Faculty of Native Studies. I am an urban Inuit writer. My M.A. Thesis is based on the Eskimo Identification Canada System which ran in Canada from 1941 to 1978. It is a system, simply put, that replaced Inuit names with numbers. The University of Alberta has been very kind towards my writing and I have been awarded the James Patrick Follinsbee Prize for Creative Prose (2011) and the Stephen Kapalka Memorial Prize for Prose (2012). My creative work, both prose and poetry, has never been published in hard copy. This does not stop me from writing and I would encourage all writers to remember that we write because of what is inside of us needing to get out onto a page.

Matna – Norma

Earth Day poems: “I’ve wanted to speak to the world for sometime now about you.”

Posted: April 22, 2013 Filed under: English, Maurice Kenny | Tags: Poems for Earth Day Comments Off on Earth Day poems: “I’ve wanted to speak to the world for sometime now about you.”Maurice Kenny (Mohawk poet and teacher, born 1929)

new song

.

We are turning

eagles wheeling sky

We are rounding

sun moving in the air

We are listening

to old stories

Our spirits to the breeze

the voices are speaking

Our hearts touch earth

and feel dance in our feet

Our minds in clear thought

we speak the old words

We will remember everything

knowing who we are

We will touch our children

and they will dance and sing

As eagle turns, sun rises, winds blow,

ancestors, be our guides

Into new bloodless tomorrows.

. . .

ceremony

.

urgent/

night/ and not

even rain could

stop love-

making

in shadows

.

street unbuckled

rain slid down neck/

nipple/crotch

exposed to hands

all elements/

ancient mouth

tender as thistle-down

swallowed centuries

.

spent urgency

.

life re-newed/continues

stories are told

under winter moons

big orange melons

purple plums

.

Seminoles dance in this light

celebrate

Comanches dance in this light

celebrate, too/together

fixed in sweat/suction

of flesh to flesh

celebrate, too

.

rain/ and rain

washes sky clean

everything

is green

green sun, green moon, green dreams

and there is only

the good feeling

.

now to sleep

. . .

curt suggests

.

Passing through,

wolf presses snow,

disappears

as though winter moon

washed the fallen snow

drifting the mountain slope.

.

He howls

and I’m assured things

of the old mountain will

not only stay but survive.

It is all about survival…

not the internet, online

or standing, waiting for a big mac.

Humans have survived,

some say, perhaps too long.

Beauty. Nobility. Poetry.

Rewards for the warrior

who brought the village fire.

.

Wolf is always hunting.

Winter is long and frozen,

dark and deadly dangerous.

Farmers are armed.

Sleep without fat is eternal

and pups are bones in enemy’s teeth.

.

The politic is not the language,

not even the song belongs to the voice

until fires are built, walls erected

and it is safe to sleep. Then sing.

.

Raccoon falls from the elm,

a high branch.

Wolf watches from the hill.

Vocables quaver.

Rocks learn to sing

in the water of the swift river.

Now we stand erect

and walk through the green woods.

Our songs are safely sculpted

into ice and pray

it won’t melt

to the touch of the ear bending to echoes.

.

I don’t care if you are only passing

through these woods. Stay.

. . .

hawkweed

.

I’ve wanted to speak to the world

for sometime now about you.

There are many who confuse you with another wild

flower which is, in truth,

no relation not even

a distant, kissing cousin.

You don’t even look alike

nor survive in the same country-side.

Many people claim you are Indian

Paint Brush. Just today

a friend spotted your bloom

decorating the roadside grasses

and called out… “O there’s a beauty…

a paint brush.” I had

to explain the brush blooms

out west…Oklahoma…and

is red. Period.

.

You, on the other hand,

blossom here in the east

and your bloom is fire-

red or orange and sometimes

yellow and you came on the

Mayflower with the others

from across the seas.

.

Farmers think the hawk eats

your blossoms for sight,

vision, but we’re happy

you show up every spring

on the roadside or in the field

bringing colour to morning

though dotted with dew

or snake-spittle, bee-balm.

Up here in the Adirondacks

I’ve seen you rise in snow

when April/May arrived late.

.

Well, all I’ve really got

to say is if the farmer is right

then the red-tail is pretty smart

and deserves your sight.

Now we have to get the the other

humans to admit just who you are.

. . . . .

All poems © Maurice Kenny, from his collection In the Time of the Present (2000)

Photograph: Hieracium caespitosum a.k.a. meadow or field hawkweed

Poems for Earth Day: “The earth of my blood”: O’Connor, Ben the Dancer, La Fortune

Posted: April 22, 2013 Filed under: Ben the Dancer, English, Lawrence William O'Connor, Richard La Fortune / Anguksuar | Tags: Native-American poets, Poems for Earth Day Comments Off on Poems for Earth Day: “The earth of my blood”: O’Connor, Ben the Dancer, La FortuneLawrence William O’Connor (Winnebago poet)

“O Mother Earth”

.

Never will I plough the earth.

I would be ripping open the breast of my mother.

.

Never will I foul the rivers.

I would be poisoning the veins of my mother.

.

Never will I cut down the trees.

I would be breaking off the arms of my mother.

.

Never will I pollute the air.

I would be contaminating the breath of my mother.

.

Never will I strip-mine the land.

I would be tearing off her clothes, leaving her naked.

.

Never will I kill the wild animals for no reason.

I would be murdering her children, my own brothers and sisters.

.

Never will I disrespect the earth in anyway.

Always will I walk in beauty upon the earth my mother,

Under the sky my father,

In the warmth of the sun my sister,

Through the glow of the moon my brother.

. . .

Ben the Dancer (Yankton Lakota-Sioux, Rosebud (Sicangu), South Dakota)

“My Rug Maker Fine”

.

slowly as I laid my head

upon his chest

the rain outside beckoned

for me to kiss him

we forgot the names that were called

and as I looked into his deep brown eyes

I saw the earth of his people

the earth of his blood

and the earth of his birth

looking at me

.

there was much to be said

on that rainy night

but talking came secondary

and not much was said

some names were meant to scald

they can break steadfast ties

then I heard the earth of his people

the earth of his blood

and the earth of his birth

telling me

.

he left on that rainy night

without a kiss

he went home forever

the rain beckoned at him to go

the earth of his people told me

he was going home

the earth of his blood called him

to come home

and the earth of his birth took him

from me

.

oh how my heart went on a dizzy flight

I will him miss

knowing this was going to sever

our hearts and leave a hole

I know the drum of his people

that called him home

I feel the pulse of his blood

that drew him there

I smell the scent of his birth

that made me let him go

.

I have endured the name

the scalding brand

I stand on my own feet now

the earth of my people

the earth of my blood

and the earth of my birth

told me to let you go

I listened

I know now

and we are free.

. . .

Richard La Fortune/Anguksuar (Yupik Eskimo, born 1960, Bethel, Kuskokvagmiut, Alaska)

.

I have picked a bouquet for you:

I picked the sky,

I picked the wind,

I picked the prairies with their waving grasses,

I picked the woods, the rivers, brooks and lakes,

I picked the deer, the wildcat, the birds and small animals.

I picked the rain – I know you love the rain,

I picked the summer stars,

I picked the sunshine and the moonlight,

I picked the mountains and the oceans with their mighty waters.

I know it’s a big bouquet, but open your arms wide;

you can hold all of it and more besides.

.

Your mind and your love will

let you hold all of this creation.

. . . . .

All poems © each poet: Lawrence William O’Connor, Ben the Dancer, Richard La Fortune

Selections are from a compilation of “Gay American Indian” (including Lesbian and Two-Spirits) poetry, short stories and essays – Living the Spirit – published in 1988.

Poems for Earth Day: Rita Joe’s “Mother Earth’s Hair”, “There is Life Everywhere” and “When I am gone”

Posted: April 22, 2013 Filed under: English, Rita Joe | Tags: Poems for Earth Day Comments Off on Poems for Earth Day: Rita Joe’s “Mother Earth’s Hair”, “There is Life Everywhere” and “When I am gone”Rita Joe (Mi’kmaw poet, 1932-2007)

“Mother Earth’s Hair”

.

In August 1989 my husband and I were in Maine

Where he died, I went home alone in pain.

We had visited each reservation we knew

Making many friends, today I still know.

Near a road a woman was sitting on the ground

She was carefully picking strands of grass

Discarding some, holding others straight

I asked why was she picking so much.

She said, “They are ten dollars a pound.”

My husband and I sat alongside of her, becoming friends.

A bundle my husband picked then, later my treasure.

I know, as all L’nu’k* know,

that sweetgrass is mother earth’s hair

So dear in my mind my husband picking shyly for me

Which he never did before, in two days he will leave me.

Today as in all days I smell sweetgrass, I think of him

Sitting there so shy, the picture remains dear.

.

*L’nu = an Aboriginal person

. . .

“There is Life Everywhere”

.

The ever-moving leaves of a poplar tree lessened my anxiety as I walked through the woods trying to make my mind work on a particular task I was worried about. The ever-moving leaves I touched with care, all the while talking to the tree. “Help me,” I said. There is no help from anywhere, the moving story I want to share. There is a belief that all trees, rocks, anything that grows, is alive, helps us in a way that no man can ever perceive, let alone even imagine. I am a Mi’kmaw woman who has lived a long time and know which is true and not true, you only try if you do not believe, I did, that is why my belief is so convincing to myself. There was a time when I was a little girl, my mother and father had both died and living at yet another foster home which was far away from a native community. The nearest neighbours were non-native and their children never went near our house, though I went to their school and got along with everybody, they still did not go near our home. It was at this time I was so lonely and wanted to play with other children my age which was twelve at the time. I began to experience unusual happiness when I lay on the ground near a brook just a few metres from our yard. At first I lay listening to the water, it seemed to be speaking to me with a comforting tone, a lullaby at times. Finally I moved my playhouse near it to be sure I never missed the comfort from it. Then I developed a friendship with a tree near the brook, the tree was just there, I touched the outside bark, the leaves I did not tear but caressed. A comforting feeling spread over me like warmth, a feeling you cannot experience unless you believe, that belief came when I was saddest. The sadness did not return after I knew that comfortable unity I shared with all living animals, birds, even the well I drew water from. I talked to every bird I saw, the trees received the most hugs. Even today I am sixty-six years old, they do not know the unconditional freedom I have experienced from the knowledge of knowing that this is possible. Try it and see. There is life everywhere, treat it as it is, it will not let you down.

. . .

“When I am gone”

.

The leaves of the tree will shiver

Because aspen was a friend one time.

Black spruce, her arms will lay low

And across the sky the eagles fly.

The mountains be still

Their wares one time like painted pyramids.

All gold, orange, red splash like we use on face.

The trees do their dances for show

Like once when she spoke

I love you all.

Her moccasin trod so softly, touching mother

The rocks had auras after her sweat

The grass so clean, she pressed it to cheek

Every blade so clean like He wants you to see.

The purification complete.

“Kisu’lkw” you are so good to me.

I leave a memory of laughing stars

Spread across the sky at night.

Try counting, no end, that’s me – no end.

Just look at the leaves of any tree, they shiver

That was my friend, now yours

Poetry is my tool, I write.

. . . . .

For more of Rita Joe’s poems please see our April 11th posts…

Alootook Ipellie: Artist, Writer, Dreamer !

Posted: April 11, 2013 Filed under: Alootook Ipellie, English, Writer-Artist-Dreamer: Alootook Ipellie Comments Off on Alootook Ipellie: Artist, Writer, Dreamer !

ZP_The agony and the ecstasy_illustration for a short story in Arctic Dreams and Nightmares_Alootook Ipellie, 1993

Alootook Ipellie (1951-2007)

“It Was Not ‘Jajai-ja-jiijaaa‘ Anymore – But ‘Amen’”

.

It was in the guise of the Holy Spirit

That they swooped down on the tundra

Single-minded and determined

To change forever the face

Of ancient Spirituals

These lawless missionaries from places unknown

Became part of the landscape

Which was once the most sacred tomb

Of lives lived long ago

The last connection to the ancient Spirits

Of the most sacred land

Would be slowly severed

Never again to be sensed

Never again to be felt

Never again to be seen

Never again to be heard

Never again to be experienced

Sadness supreme for the ancient culture

Jubilation in the hearts of the converters

Where was justice to be found?

They said it was in salvation

From eternal fire

In life after death

And unto everlasting Life in Heaven

A simple life lived

On the sacred land was no more

The psalm book now replaced

The sacred songs of shamans

The Lord’s Prayer now ruled

Over the haunting chant of revival

It was not ‘Jajai-ja-jiijaaa’ anymore

But-

‘Amen’

. . .

“How noisy they seem”

.

I saw a picture today, in the pages of a book.

It spoke of many memories of when I was still a child:

Snow covered the ground,

And the rocky hills were cold and gray with frost.

The sun was shining from the west,

And the shadows were dark against the whiteness of the

Hardened snow.

.

My body felt a chill

Looking at two Inuit boys playing with their sleigh,

For the fur of their hoods was frosted under their chins,

From their breathing.

In the distance, I could see at least three dog teams going away,

But I didn’t know where they were going,

For it was only a photo.

I thought to myself that they were probably going hunting,

To where they would surely find some seals basking on the ice.

Seeing these things made me feel good inside,

And I was happy that I could still see the hidden beauty of the land,

And know the feeling of silence.

. . .

“Walking Both Sides of an Invisible Border”

.

It is never easy

Walking with an invisible border

Separating my left and right foot

I feel like an illegitimate child

Forsaken by my parents

At least I can claim innocence

Since I did not ask to come

Into this world

Walking on both sides of this

Invisible border

Each and everyday

And for the rest of my life

Is like having been

Sentenced to a torture chamber

Without having committed a crime

Understanding the history of humanity

I am not the least surprised

This is happening to me

A non-entity

During this population explosion

In a minuscule world

I did not ask to be born an Inuk

Nor did I ask to be forced

To learn an alien culture

With its alien language

But I lucked out on fate

Which I am unable to undo

I have resorted to fancy dancing

In order to survive each day

No wonder I have earned

The dubious reputation of being

The world’s premier choreographer

Of distinctive dance steps

That allow me to avoid

Potential personal paranoia

On both sides of this invisible border

Sometimes the border becomes so wide

That I am unable to take another step

My feet being too far apart

When my crotch begins to tear

I am forced to invent

A brand new dance step

The premier choreographer

Saving the day once more

Destiny acted itself out

Deciding for me where I would come from

And what I would become

So I am left to fend for myself

Walking in two different worlds

Trying my best to make sense

Of two opposing cultures

Which are unable to integrate

Lest they swallow one another whole

Each and everyday

Is a fighting day

A war of raw nerves

And to show for my efforts

I have a fair share of wins and losses

When will all this end

This senseless battle

Between my left and right foot

When will the invisible border

Cease to be.

.

(1996)

. . . . .

Alootook Ipellie

“Self-Portrait: Inverse Ten Commandments” (1993)

.

I woke up snuggled in the warmth of a caribou-skin blanket during a vicious storm. The wind was howling like a mad dog, whistling whenever it hit a chink in my igloo. I was exhausted from a long, hard day of sledding with my dogteam on one of the roughest terrains I had yet encountered on this particular trip.

.

I tried going back to sleep, but the wind kept waking me as it got stronger and even louder. I resigned myself to just lying there in the moonless night, eyes open, looking into the dense darkness. I felt as if I was inside a black hole somewhere in the universe. It didn’t seem to make any difference whether my eyes were opened or closed.

.

The pitch darkness and the whistling wind began playing games with my equilibrium. I seemed to be going in and out of consciousness, not knowing whether I was still wide awake or had gone back to sleep. I also felt weightless, as if I had been sucked in by a whirlwind vortex.

.

My conscious mind failed me when an image of a man’s face appeared in front of me. What was I to make of his stony stare – his piercing eyes coloured like a snowy owl’s, and bloodshot, like that of a walrus?

.

He drew his clenched fists in front of me. Then, one by one, starting with the thumbs, he spread out his fingers. Each finger and thumb revealed a tiny, agonized face, with protruding eyes moving snake-like, slithering in and out of their sockets! Their tongues wagged like tails, trying to say something, but only mumbled, since they were sticking too far out of their mouths to be legible. The pitch of their collective squeal became higher and higher and I had to cover my ears to prevent my eardrums from being punctured. When the high pitched squeal became unbearable, I screamed like a tortured man.

.

I reached out frantically with both hands to muffle the squalid mouths. Just moments before I grabbed them, they faded into thin air, reappearing immediately when I drew my hands back.

.

Then there was perfect silence.

I looked at the face, studying its features more closely, trying to figure out who it was. To my astonishment, I realized the face was that of a man I knew well. The devilish face, with its eyes planted upside down, was really some form of an incarnation of myself! This realization threw me into a psychological spin.

.

What did this all mean? Did the positioning of his eyes indicate my devilish image saw everything upside down? Why the panic-stricken faces on the tips of his thumbs and fingers? Why were they in such fits of agony? Had I indeed arrived at Hell’s front door and Satan had answered my call?

.

The crimson sheen reflecting from his jet-black hair convinced me I had arrived at the birthplace of all human fears. His satanic eyes were so intense that I could not look away from them even though I tried. They pulled my mind into a hypnotic state. After some moments, communicating through telepathy, the image began telling me horrific tales of unfortunate souls experiencing apocalyptic terror in Hell’s Garden of Nede.

.

The only way I could deal with this supernatural experience was to fight to retain my sanity, as fear began overwhelming me. I knew it would be impossible for me to return to the natural, physical world if I did not fight back.

.

This experience made my memory flash back to the priestly eyes of our local minister of Christianity. He had told us how all human beings, after their physical death, were bound by the doctrine of the Christian Church that they would be sent to either Heaven or Hell. The so-called Christian minister had led me to believe that if I retained my good-humoured personality toward all mankind, I would be assured a place in God’s Heaven. But here I was, literally shrivelling in front of an image of myself as Satan incarnate!