Loving the Ladies: the poems of Pat Parker

Posted: June 29, 2013 Filed under: English, Pat Parker | Tags: Black lesbian poets Comments Off on Loving the Ladies: the poems of Pat Parker ZP_Pat Parker in 1989_photograph © Robert Giard

ZP_Pat Parker in 1989_photograph © Robert Giard

Pat Parker

“Sunshine”

.

If it were possible

to place you in my brain

to let you roam around

in and out

my thought waves

you would never

have to ask

why do you love me?

.

This morning as you slept

I wanted to kiss you awake

say I love you till your brain

smiled and nodded yes

this woman does love me.

.

Each day the list grows

filled with the things that are you

things that make my heart jump

yet words would sound strange

become corny in utterance.

.

In the morning when I wake

I don’t look out my window

to see if the sun is shining.

I turn to you instead.

. . .

“I have”

.

i have known

many women

and the you of you

puzzles me.

.

it is not beauty

i have known

beautiful women.

.

it is not brains

i have known

intelligent women.

.

it is not goodness

i have known

good women.

.

it is not selflessness

i have known

giving women.

.

yet you touch me

in new

different

ways.

.

i become sand

on a beach

washed anew with

each wave of you.

.

with each touch of you

i am fresh bread

warm and rising.

.

i become a newborn kitten

ready to be licked

and nuzzled into life.

.

you are my last love

and my first love

you make me a virgin

and I want to give myself to you.

. . .

“Sublimation”

.

It has been said that

sleep is a short death.

I watch you, still,

your breath moving –

soft summer breeze.

Your face is velvet

the tension of our love,

gone.

No, false death is not here

in our bed

just you – asleep

and me – wanting

to make love to you,

writing words instead.

. . .

“Metamorphosis”

.

you take these fingers

bid them soft

a velvet touch

to your loins

.

you take these arms

bid them pliant

a warm cocoon

to shield you

.

you take this shell

bid it full

a sensual cup

to lay with you

.

you take this voice

bid it sing

an uncaged bird

to warble your praise

.

you take me, love,

a sea skeleton

fill me with you

and I become

pregnant with love

give birth

to revolution.

. . .

“For Willyce”

.

When i make love to you

i try

with each stroke of my tongue

to say

i love you

to tease

i love you

to hammer

i love you

to melt

i love you

and your sounds drift down

oh god!

oh jesus!

and i think

here it is, some dude’s

getting credit for what

a woman

has done

again.

. . .

Pat Parker (1944-1989) was a Black-American lesbian and feminist. She was born in Houston, Texas, and lived and worked (at a women’s health centre) in Oakland, California, from 1978 almost up until her death from breast cancer. Racism, misogyny, homophobia – Parker “kept it real” about such facts at numerous poetry readings throughout the 1970s. She had had two marriages – and raised two children from them – but when her second marriage ended in divorce she journeyed down a different road, stating: “After my first relationship with a woman, I knew where I as going.” Known for her “hard truths” in poems such as “Exodus”, “Brother”, “Questions” and “Womanslaughter”, Parker also had a whole other lesser-known side to her as a poet who made love poems – several of which we present here. Some are tender and euphoric and one – “For Willyce” – has Parker’s characteristic ‘edge’.

. . . . .

From Lagos with Love: two gay poets

Posted: June 29, 2013 Filed under: Abayomi Animashaun, English, Rowland Jide Macaulay | Tags: African gay poets Comments Off on From Lagos with Love: two gay poets ZP_Pastor Macaulay leading a House of Rainbow gathering of conversation and loving prayer

ZP_Pastor Macaulay leading a House of Rainbow gathering of conversation and loving prayer

.

Rowland Jide Macaulay (born 1966) is an openly gay Nigerian poet and pastor who – as of tomorrow (June 30th 2013) will also be an ordained preacher in The Church of England. He begins duties as a curate in London this July and says that his will be “an inclusive parish ministry – and I cannot wait!”

Macaulay’s involvement in church activity has deep roots. He was raised Pentecostal in Lagos, where his father, Professor Augustus Kunle Macaulay, is the principal of Nigeria’s United Bible University.

But the truth of his sexuality needed telling and Rowland reached a juncture in the spiritual road, founding House of Rainbow Fellowship which gives pastoral care to sexual minorities in Nigeria, and includes sister fellowships in Ghana, Lesotho and several other African states.

The Easter story holds great power for Macaulay; the following is a poem he wrote in 1999:

.

Rowland Jide Macaulay

“In Just Three Days”

.

For a life time

He came that we may have life

He died that we may have life in abundance.

In Just Three Days

Better known than ever before

Crowned King of kings

Tired but never gave up

Alone, forsaken and frightened

The world is coming to a close

Doors closing, wall to wall thickening.

In Just Three Days

Prophecies have been fulfilled

Unto us a child is born…

Destroy the world and build the kingdom

Followers deny His existence

His betrayer will accompany the enemy.

In Just Three Days

The world had Him and lost Him

Chaos in the enemies’ camp

Death could not hold Him prisoner

In the grave, Jesus is Lord.

Bethany, the house of Simon the leper,

Alabaster box of precious oil

Ointment for my body

Gethsemane, place of my refuge

Watch and pray.

In Just Three Days

Destruction, Rebuilding

Chastisement, Loving, Caring

Killing, Survival

Mockery, Praises

Passover, Betrayal

The people, The high priest

Crucify him, crown of thorns

Hail him, Strip him, bury him.

In Just Three Days

He is risen

Come and see the place where the Lord lay

His arrival in the clouds of heaven.

In Just Three Days

He was dead and buried

My resurrection, my hope, my dream

Hopelessness, helplessness turned around

In Just Three Days

In Just Three Days.

. . .

Nigerian Abayomi Animashaun, now living in the U.S.A., completed a university degree in mathematics and chemistry but then took that precise quantum leap into the ever-expanding universe that is Poetry. He teaches at The University of Wisconsin (Oshkosh).

The following poem is from his 2008 collection, The Giving of Pears.

.

Abayomi Animashaun

“In bed with Cavafy”

.

After pleasing each other,

We laid in bed a long time…

Curtains drawn,

Bolt fastened,

We’d been cautious,

Had made a show for others—

We ordered meat and wine

From the local restaurant.

And, like other guys, we talked loud

About politics into the night,

But whispered about young men

We’d bent in the dark.

At midnight, when from the bars drunks

Staggered onto the streets,

We shook hands the way they did,

Laughed their prolonged laughs,

And warned each other to steer clear

From loose girls and diseases—

All the while knowing

He’ll circle round as planned,

Sit in the unused shack behind my house

Till my neighbours’ candles are blown out.

And, after his soft knock,

I’ll slowly release the latch

– As I did last night.

. . .

Editor’s note: “In bed with Cavafy” captures the mood, nuance, and subtle tone of the poetic voice of Constantine Cavafy (1863-1933), the homosexual Greek poet who was a native of Alexandria, Egypt. Animashaun updates this Cavafy-an “voice”, making it heard in his description of two bisexual lovers in Lagos who are caught up in strategies of social hypocrisy and secret honesty in a place where sexual open-ness means great personal risk.

.

Special Thanks to Duane Taylor (York University, Toronto) for his editorial assistance!

. . . . .

Frank Mugisha: “People say I am their inspiration – but they are an inspiration to me – so I can never talk about leaving the country.”

Posted: June 29, 2013 Filed under: English | Tags: LGBT Rights Activists in Africa Comments Off on Frank Mugisha: “People say I am their inspiration – but they are an inspiration to me – so I can never talk about leaving the country.” ZP_Frank Mugisha at the First Uganda Pride March on August 4th, 2012_The March took place on the shores of Victoria Lake, outside of Entebbe, away from Uganda’s bustling capital, Kampala. Mugisha, as Captain Pride in a rainbow-sashed sailor suit, told journalist Alexis Okeowo: “I just wish I had a switch to turn on that would make everyone who’s gay say they are gay. Then everyone who is homophobic can realize their brothers, their sisters, and their aunts are gay.” He told another reporter: “Next time we begin the march from the police station [in Kampala]…”

ZP_Frank Mugisha at the First Uganda Pride March on August 4th, 2012_The March took place on the shores of Victoria Lake, outside of Entebbe, away from Uganda’s bustling capital, Kampala. Mugisha, as Captain Pride in a rainbow-sashed sailor suit, told journalist Alexis Okeowo: “I just wish I had a switch to turn on that would make everyone who’s gay say they are gay. Then everyone who is homophobic can realize their brothers, their sisters, and their aunts are gay.” He told another reporter: “Next time we begin the march from the police station [in Kampala]…”

. . .

The Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network’s 5th Symposium on HIV, Law and Human Rights was held in Toronto on June 13th and 14th, 2013. One of the events was “A conversation with Frank Mugisha” which took place at the Toronto Reference Library, attended by about 300 people. The CBC’s Ron Charles interviewed Mr. Mugisha in front of the audience, members of whom asked questions at the end.

The diminutive 30-year old Mugisha was calm and reasonable throughout, coming across as a man who has had to do some hard thinking and to strategize with love. He spoke about new voices for LGBT rights in Uganda – mainly, but not only – in Kampala; about threats to the emerging community: American author and anti-Gay activist Scott Lively and his pivotal “The Homosexual Agenda” slide-show and lecture in 2009; Ugandan M.P. David Bahati and his stalled Anti-Homosexual parliamentary bill; and angry anti-Gay protests in the streets after Ugandan tabloid newspaper “Rolling Stone” published names and addresses of Kampala “Homos”, stating: “Hang them!”. Mugisha spoke also of David Kato, one of the founders of Ugandan human-rights organization S.M.U.G. (Sexual Minorities Uganda), murdered in 2011 because of his outspoken-ness, and who also campaigned for children’s and women’s rights; and of former Ugandan Bishop Christopher Senyonjo, an Anglican clergyman who is still a vocal defender of LGBT rights.

He said he is looking forward to the 2nd Uganda Pride March – to be held during the summer of 2013 – and he confirmed his own religious faith; he is still a Christian, still a Catholic. Asked by Ron Charles what keeps him in Uganda – where he requires a chaperone wherever he goes and must carefully plan his movements – when he could find asylum in other nations, Mugisha said: “People say I am their inspiration – but they are an inspiration to me – so I can never talk about leaving the country. Why do I keep smiling? I try to keep a positive attitude after all the bad stories I’ve heard and I want to put a human face on our work. ‘Those people’ – what some Ugandans call homosexuals – are they devils, selling their bodies, molesting children? – well, I try to reach these Ugandans who do not know us, I try to reach them one on one.”

Finally, Mugisha suggested to Charles that Progressive Christian voices need to speak up, and sensitive international diplomacy should be applied on such a “delicate” issue as homosexuality in Uganda; that media shock tactics will harm those most vulnerable plus inflame the majority. He said that if money comes to Uganda to do good – then “follow the money” and make sure that human-rights issues in Uganda are being addressed as a group, because it’s not just about homosexuality. Mugisha reminded the audience that the South African government has spoken out against the anti-Gay movement in Uganda, and that Cameroon, Nigeria, Tanzania and Zambia are more homophobic – voices are silenced – than Uganda which is by and large known for the warm-heartedness of its people. Charles finished by asking the obvious question: what does the future hold for LGBT rights in Uganda? Mugisha spoke methodically, thoughtfully, as he had for the entire hour and a half: “I don’t think there will be acceptance – in my lifetime. But tolerance, yes. Perhaps even anti-hate-crimes legislation.”

.

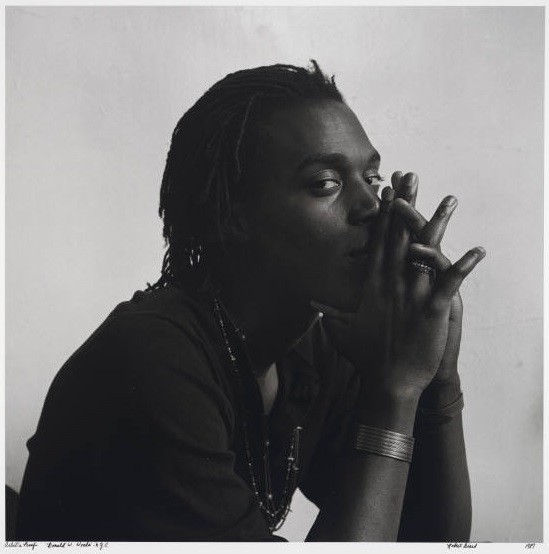

ZP_Teacher and LGBT activist David Kato (1964 – 2011), the first publicly gay man in Uganda

ZP_Teacher and LGBT activist David Kato (1964 – 2011), the first publicly gay man in Uganda

ZP_Juliet Victor Mukasa, a founder, with David Kato, of S.M.U.G. (Sexual Minorities Uganda)

ZP_Juliet Victor Mukasa, a founder, with David Kato, of S.M.U.G. (Sexual Minorities Uganda)

.

The following is an interview with Frank Mugisha by journalist Elizabeth Palmberg from March 2013. We thank Soujourners website (“Faith in Action for Social Justice”) for provision of this text:

1. What’s your response to the letter U.S. religious leaders signed last year, which condemned the “Anti-Homosexuality Bill” before Uganda’s Parliament because it “would forcefully push lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people further into the margins”?

Mugisha:

Uganda is a very Christian country. About 85 percent of our population is Christian—Anglican, Catholic, and Pentecostal. So for religious leaders to speak out against the Ugandan legislation, that is very important for me and for my colleagues in Uganda, because it speaks not only to the politicians and legislators, but also to the minds of the ordinary citizens.

It is very important to have respected religious leaders involved, including Archbishop Desmond Tutu, because these are leaders who have spoken out on other human rights issues such as apartheid, women’s rights, and slavery. And for us, for the voice of LGBT rights, to join with these other issues, clearly indicates that our movement is fighting for human rights.

2. Before Parliament adjourned without passing the “kill the gays” bill, an official had suggested it would pass as a “Christmas gift.” As a Catholic yourself, what’s your response to that image?

Mugisha:

What I’ve always said is that instead of promoting hatred, we should promote love. And clearly, this law has so much discrimination, the language is full of hatred; this is not appropriate for Jesus’ birthday, because he said love your God and love your neighbour as you love yourself—those are the greatest commandments.

3. As an African, how do you see all this?

Mugisha:

The bill itself violates our own culture as Africans, because Africans are people who are united to each other, but this bill clearly divides. For example, it includes a clause that says that every person should report any “known homosexual” to authorities, and failure to do that becomes criminal—it calls for a witch hunt that was never seen in African culture. The bill also criminalizes the “promotion of homosexuality,” which would criminalize any kind of dialogue or talk about homosexuality in my country.

4. Would it require clergy to turn in gay members of their flocks?

Mugisha:

Yes, priests taking confession and any religious leader—whether giving health support, psychosocial counseling, or anything—are required to go and report to the authorities. So this totally violates Christian teaching, including the Catholic faith.

5. Does the bill threaten efforts to fight HIV?

Mugisha:

Even if the death penalty is removed, the legislation itself will drive LGBT people underground—already now, without the bill passing, there’s fear. People are afraid to go to health workers and say that they’re in same-sex relations, so this will happen underground, with no information, and that will greatly increase the spread of HIV/AIDS.

6. What message do you have for Christians in the U.S.A.?

Mugisha:

It is important for people to know that there has been a lot of influence from American fundamentalist Christians in promoting this hatred in Uganda; some of them have been very vocal. We think that Christians in the U.S.A. should hold these preachers accountable.

. . . . .

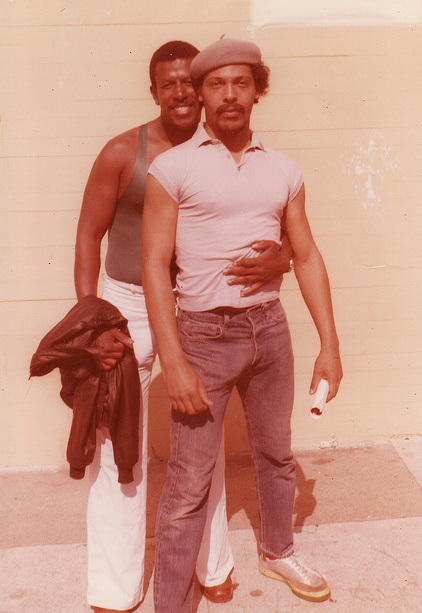

ZP_Two 27-year-old Zulu men, Thoba Sithole and Tshepo Modisane, married in the town of KwaDukuza in April 2013. South Africa legalized same-sex marriage in 2006.

ZP_Two 27-year-old Zulu men, Thoba Sithole and Tshepo Modisane, married in the town of KwaDukuza in April 2013. South Africa legalized same-sex marriage in 2006.

. . . . .

“That poem which lay in my heart like a secret”: Juliane Okot Bitek reflects upon Okot p’Bitek’s “Return the Bridewealth” and the role of the poet

Posted: June 24, 2013 Filed under: 7 GUEST EDITORS, English, Juliane Okot Bitek, Juliane Okot Bitek, Okot p’Bitek Comments Off on “That poem which lay in my heart like a secret”: Juliane Okot Bitek reflects upon Okot p’Bitek’s “Return the Bridewealth” and the role of the poetOur warmest thanks to Juliane Okot Bitek for the following Guest Editor post at Zócalo Poets:

.

Okot p’Bitek (1931 – 1982)

Return the Bridewealth (1971)

.

I

.

I go to my father

He is sitting in the shade at the foot of the simsim granary,

His eyes are fixed on the three graves of his grandchildren

He is silent.

Father, I say to him,

Father, gather the bridewealth so that I may marry the

Girl of my bosom!

My old father rests his bony chin in the broken cups of his

withered hands,

His long black fingernails vainly digging into the tough

dry skin of his cheeks

He keeps staring at the graves of his grandchildren,

Some labikka weeds and obiya grasses are growing on the mounds.

My old father does not answer me, only two large clotting

tears crawl down his wrinkled cheeks,

And a faint smile alights on his lips, causing them to

quiver and part slightly.

He reaches out for his walking staff, oily with age and

smooth like the long teeth of an old elephant.

One hand on his broken hip, he heaves himself up on

three stilts,

His every joint crackling and the bones breaking.

Hm! he sighs and staggers towards the graves of his

Grandchildren,

And with the bone-dry staff he strikes the mounds: One!

Two! Three!

He bends to pluck the labikka weeds and obiya grasses,

But he cannot reach the ground, his stone-stiff back cracks

like dry firewood.

Hm! he sighs again, he turns around and walks past me.

He does not speak to me.

There are more clotting tears on his glassy eyes,

The faint smile on his broken lips has grown bigger.

.

II

.

My old mother is returning from the well,

The water-pot sits on her grey wet head.

One hand fondles the belly of the water pot, the other

strangles the walking staff.

She pauses briefly by the graves of her grandchildren and

studies the labikka weeds and the obiya grasses waving

Like feathers atop the mounds.

Hm! she sighs

She walks past me;

She does not greet me.

Her face is wet, perhaps with sweat, perhaps with water

from the water-pot,

Perhaps some tears mingle with the water and the sweat.

The thing on her face is not a smile,

Her lips are tightly locked.

She stops before the door of the hut,

She throws down the wet walking staff, klenky, klenky!

A little girl in a green frock runs to her assistance;

Slowly, slowly, steadily she kneels down;

Together slowly, slowly, gently they lift the water-pot and

put it down.

My old mother says, Thank you!

Some water splashes onto the earth, and wets the little

girl’s school books.

She bursts into tears, and rolls on the earth, soiling her

beautiful green frock.

A little boys giggles.

He says, All women are the same, aren’t they?

Another little boy consoles his sister.

.

III

.

I go to the Town,

I see a man and a woman,

He wears heavy boots, his buttocks are like sacks of cotton,

His chest resembles the simsim granary,

His head is hidden under a broad-brimmed hat.

In one hand he holds a loaded machine-gun, his fingers at

the trigger,

His other hand coils round the waist of the woman, like a

starving python.

They part after a noisy kiss.

Hm! he sighs.

Hm! she sighs.

He marches past me, stamping the earth in anger, like an

elephant with a bullet in his bony head.

He does not look at me,

He does not touch me; only the butt of his weapon

touches my knee lightly,

He walks away, the sacks of cotton on his behind rising and

falling alternately

Like a bull hippo returning to the river after grazing in

the fresh grasses.

Hm! I sigh.

I go to the woman,

She does not look up to me,

She writes things in the sand.

She says, How are my children?

I say, Three are dead, and some labikka weeds and obiya

grasses grow on their graves.

She is silent.

I say, your daughter is now in Primary Six, and your little

boys ask after you!

The woman says, My mother is dead.

I am silent.

The agoga bird flies overhead,

He cries his sorrowful message:

She is dead! She is dead!

The guinea-fowl croaks in the tree near by:

Sorrow is part of me,

Sorrow is part of me. How can I escape

The baldness of my head?

She is silent.

Hm! I sigh.

She says, I want to see my children.

I tell the woman I cannot trace her father.

I say to her I want back the bridewealth that my father

paid when we wedded some years ago,

When she was full of charm, a sweet innocent

little hospital ward-maid.

She is silent.

I tell the woman I will marry the girl of my bosom,

I tell her the orphans she left behind will be mothered, and

the labikka weeds and obiya grasses

that grow on the graves of her children

will be weeded,

And the ground around the mounds will be kept tidy.

Hm! she sighs.

She is silent.

I am silent.

The woman reaches out for her handbag.

It is not the one I gave her as a gift last Christmas.

She opens it

She takes out a new purse

She takes out a cheque.

She looks up to me, our eyes meet again after many

months.

There are two deep valleys on her cheeks that were not

there before,

There is some water in the valleys.

The skin on her neck is rotting away,

They say the doctor has cut her open and

removed the bag of her eggs

So that she may remain a young woman forever.

I am silent

A broad witch-smile darkens her wet face,

She screams,

Here, take it! Go and marry your bloody woman!

I unfold the cheque.

It reads:

Shillings One thousand four hundred only!

. . .

Juliane Okot Bitek

A Poet May Lie Down Beside You

.

She might even let you run your palm over her hip

Round and round and round

So you remember what it’s like to lie down beside a woman

A poet may lie down beside you and listen to you sigh

Turn around, turn around

She may even take in your stories of days gone by

Turn around, turn around

Spit roasting like pigs

It’s been bloody weeks

It’s been long, stone years

Since you lay down beside a woman, anyone

A poet may lie down beside you

Let you bring the covers over her shoulders and

Lift the hair off her face

She will take you back to the lean months, lean years, two

Or has it been three?

She will take you all the way back to a time without kisses

Without touch

Forever since anyone touched you

A poet will take you back

And return with the clingy scent of yesterday

For several moments

Before this, before this

A poet might even let you kiss her

She might open up ovens and ovens of pent up heat inside you

A poet will let you think

That this is what it means

To lie down beside a woman

Rolling, rolling, drowning, searching

A poet may lie down beside you

And sing, or not sing, speak, or not speak

This is your time

A poet will not let a moment like this go wasted

So she lies down beside you and lets you touch her

So you know what it’s like

To lie down beside a woman.

. . .

I first encountered “Return the Bridewealth” in Poems from East Africa, a 1971 anthology edited by David Rubadiri and David Cook. It was a text that we used at Gayaza High School in Kampala, Uganda. It was a text from which our teachers found creative ways of engaging us with poetry. One teacher had us write a short story that incorporated the title of Jared Angira’s “No Coffin, No Grave” as the last words. Another teacher had us think about ways that we could have ‘built the nation,’ a lesson on citizenship based on Henry Barlow’s “Building the Nation”. And the fact that Barlow’s daughter was on the teaching faculty was not lost on us, even though she wasn’t the literature teacher for that class. I prayed that we would not study “Return the Bridewealth” or “They Sowed and Watered” – both poems were in the same anthology – and both had been written by my father – Okot p’Bitek.

I used to imagine that the teacher might put the burden on me to explain what the poet’s intention was as they did in the old days, as if anyone would know. I couldn’t have known what his intentions were in writing poetry and yet I was aware, even then, that my father’s poetry read like the truth. But I wasn’t mature enough to discern whether he wrote factually about everything. I was embarrassed to think that it might have dissolved into a class discussion in which my father would’ve had to beg his father and an ex-wife for money to get married. Perhaps the teachers knew not to assign those poems for our class, but that poem that read like a story (“Return the Bridewealth”) stayed with me over the years. I read my father’s other works and, after grad school, I was finally confident enough to discuss my father as a poet, an essayist, a novelist and a philosopher. But I never talked about that poem which lay in my heart like a secret, even though it remains a public document.

“Return the Bridewealth” reads true. It reads true because the poet, my dad, had an eye and an ear for the environment around a story. It wasn’t just the plot with main characters whose lives spanned time before and after the poem begins and ends. We hear the old woman’s stick: klenky, klenky! We see the old man’s fingers digging into his bony cheeks; we understand the insistence of weeds and the infuriation of the old couple who cannot maintain the graves of their grandchildren. This couple, who has endured the divorce of their son and his wife, are struggling to take care of their grandchildren, both dead and alive. And their son has the gall to return and ask for financial support to remarry.

It is a modern story, immediate and accessible. The poetry is in the language, the lines and the delivery of what might have been a short story by another writer and perhaps a novel by another’s hand. My dad boiled this story down to its bare bones and it still resists the notion that it could be a poem that celebrates its use of language and calls for attention to its lyricism.

For a man who founded the song school of poetry, Okot p’Bitek’s “Return the Bridewealth” is not a song, even though it is punctuated by the refrained sighs of all the main characters: Hm! the mother sighs; Hmm! The father sighs; Hm! the woman sighs. Hm!, the soldier sighs; Hm! I, the narrator sighs. The sigh may be a long and breathy sigh but as any Ugandan knows, hm is short and decisive. It means everything and sometimes it means nothing. But the boy giggles and the girl cries. The boy also says within earshot of his father: All women are the same, aren’t they? before he turns to console his sister.

Each conversation in “Return the Bridewealth” allows the reader to be a voyeur of the most intimate conversations. A grown man asks his elderly father for money. A boy shares a moment with his father, deriding all women and girls. A man confronts his ex-wife in an exercise that is fraught with pain and shame – neither parent is taking care of the kids and the money that will change hands is probably from the woman’s current lover in order that the man may marry his current lover – an extremely uncomfortable situation for which the title of the poem is wholly inadequate.

Okello Oculi, another poet from the same anthology, and a contemporary of Okot p’Bitek, includes this poem as one of many works that espouse shame as a trope for post colonial narratives on the fallout from having been colonized by foreigners. Sure, but we also see that there has to be shame from the behaviour of the children’s parents because we know those parents; we are those parents. We screw up, and sometimes, as parents, we don’t get our priorities right.

The poem is broken up into representations of the past, present and future. In the first section, the first person narrator introduces his father, an old man in the twilight of his life, a man whose bony fingers seem to be in the business of hastening his own death by clawing at his face. We’re brought into a home in which there are three buried children who lie in unkempt graves. It is a sorry homestead with a lovesick son who has returned for financial support from his father. His father doesn’t answer the request for money but a smile plays about the old man’s face, perhaps in hope for better circumstances still to come. The second section is a portrayal of the current state of affairs. The grandmother is still involved in the heavy domestic work, even at her advanced age, but her granddaughter is sensitive enough to go and help offload the precious cargo of water. The grade six girl’s and her grandmother’s struggle is symbolized by the water spilling onto the girl’s school textbook. The old woman does not acknowledge her son’s presence. She does not greet him and she doesn’t smile as her husband does. Her anger is evident from the way she “strangles” her walking stick and the “thing on her face” that is not a smile, but she reserves her thanks for her granddaughter who helps her with the heavy water pot on her head. The current state of affairs doesn’t belie the reality of the graves in the homestead from which the weeds are an affront; things are not as they should be.

In the third section, the narrator confronts his ex-wife who has just met up with her lover, a soldier whose well-fed form is represented by the way he fills out the bottom of his pants (“his buttocks are like sacks of cotton”). The woman wants to know about her children, but in the classic tension-filled relationship of exes, the man won’t give her the information she needs. Power plays and replays itself. The woman reveals that her mother is dead. No empathy from her ex. I can’t find your father to get my money back, the man says in response. And the woman, infuriated, writes a cheque which she retrieves from a handbag that the man realizes is not the one he bought for her last Christmas. She’s moved on. This is the present reality for many of us. We know about memory and the power of “stuff”. And this is the future because we witness a man accepting financial support from his ex-wife in order to marry the woman he’s in love with. Power reveals itself in a cash transaction.

Beyond the direct effects of colonialism which colour the poem, the culture of the Acholi people from which my father drew much inspiration, is in flux. Bridewealth, which was the purview of the man’s family, is now dependent on whoever has the money to pay for it – in this case, the man’s ex-wife and, presumably, her lover. The narrator unfolds the cheque to make sure of the amount – One Thousand Four Hundred only. In this modern cash economy, money can and does replace the former symbol of wealth – cattle. Much of the cattle of Acholi was lost in the war that lasted over two decades (1986-2007) and there are barely any Acholi cows with which to show prosperity. The narrator, emasculated by his ex-wife’s cheque, is the modern man, and there’s no shame – or is there? Who or what makes an Acholi man or woman marriageable?

My father’s only novel, a slim book titled White Teeth (first published in 1963 in the Acholi language as Lak Tar) is about a young man from an impoverished family who makes the journey to the capital, Kampala, to see if he can earn the money to pay the bride price for Cecilia Laliya, the woman he loves. Set in colonial times, just before Independence, the main character, Okeca Ladwong, is alienated by the skyscrapers, tarmac roads, traffic, a multi-ethnic society and the fast, fast pace of urban life. But he is buoyed by his love for Cecilia, and so he perseveres until he makes enough money to return to his hometown, Gulu. Okot p’Bitek, who argued against the willful discarding of Acholi culture for a modern and souless life, wouldn’t and couldn’t let Okeca return to Gulu and marry Cecilia with his newly-earned cash. That’s not the way it was done traditionally.

In Song of Lawino, it’s clear that Lawino, the spurned wife of a modern man, Ocol, can see the danger of rejecting one’s culture wholesale. Do not uproot the pumpkin, she keeps saying. Do not uproot the pumpkin. There’s no need to reject the wisdom of Acholi culture for modern ways. In “Return the Bridewealth,” the old man sighs, as does the old woman, the narrator, his ex-wife and her lover. All the adults know and express that something is terribly wrong. Hm! as they still say in Uganda. Hm!

“Return the Bridewealth” is certainly set in a time of flux for the narrator, his parents, children and ex-wife. Published in 1971, it was a time of instability in Uganda as well. 1971 was the year that Idi Amin overthrew the government of the man who had exiled my father – Apolo Milton Obote. Being the man that he was, Idi Amin did not want my father in the country either, so Okot p’Bitek remained in exile and brought us up in neighbouring Kenya, where I was born. Before Idi Amin was overthrown by organized exiles and with the support of the Tanzanian government in 1979, my father told of visiting Obote in Arusha, Tanzania, where the former president lived, and how they’d had a toast together to the life of an exile. My family returned from exile in 1980. Uganda experienced a series coup d’etats and a general election in 1980 that was heavily contested and led to the creation of a guerrilla movement that sought to overthrow the government of Milton Obote. That government was known as Obote II, given the fact that it was the second time in Obote’s career that he claimed presidency of the country.

In 1982, during the second term of my first year of high school, my father died. It was a surreal time. Dad had driven me to the bus stop at the beginning of that term where I’d caught the bus to Gayaza. I recall nothing about the drive there, not even if we talked, or what we might have talked about. I remember that he said bye very brightly and waved for a long time as he drove away. Maybe I remember a bright goodbye and a long wave because I need to.

I am a graduate student working on a PhD in interdisciplinary studies at the University of British Columbia, in Vancouver, Canada, but I’ve dabbled in creative writing for much of my life. My Bachelor’s Degree was in Fine Art with a focus on Creative Writing, so the question of the role of the poet isn’t incidental to me. I’ve thought about it. When my father wrote his Horn of My Love, a collection of Acholi songs, he declared in that book that poets were loved and feared in Acholi society. In Vancouver, love and fear are not what I associate with poets and poetry. There are small and passionate groups of poets, generally divided into the textual kind and the spoken-word kind, but they exist in a parallel universe for most of the general population. Sometimes, a local poet breaks through the barrier and everybody can see themselves in a poet’s work. Shane Koyzcan, a Vancouver poet, was one of the featured presenters at the Opening Ceremony of the 2010 Winter Olympics which was held in Vancouver. Recently, Koyzcan presented a poem on bullying, “To This Day”, at the TED talks, to much critical and popular acclaim. Like Okot p’Bitek, Koyczan’s poetry sounds like life. Nine million viewers have viewed “To This Day” on YouTube, generating thousands of responses from people who could relate to the poem. What is it about poems and poets and poetry?

I write poems, sometimes. I had my first poem published when I was a girl; I wrote it in response to the factions that were struggling for power in Uganda after the liberation war in April 1979 that saw the overthrow of Idi Amin. One afternoon, my father took me to The NationNewspaper offices in Nairobi and I was interviewed and photographed. That Sunday, my poem was published in the children’s section of that national newspaper.

In 1998, my Words in Black Cinnamon was published by Delina Press. In that book, I wrote about spurned love, dislocation and home, but nothing about what it means to be a poet. I considered poetry as one of the arts, one of the practices that human beings use to connect and reflect, but I never saw myself “connected” until Ali Farzat, the Syrian cartoonist, was tortured for his work. I wrote “A Poem for Ali Farzat” after several weeks of having heard about the torture of Farzat. I realized that I cannot afford the luxury of writing as an independent artist, making beauty for beauty’s sake. Art has a political function. It can drive change. It can make people think about what’s important to them. And for those of us who seek to work in solidarity with others, it can strengthen our resolve for change in the face of so much power against those that dare to present a dissenting voice. Today, it’s the protests in Turkey, the war in Syria, the dissenting young man who’s holed up in a hotel in Hong Kong while thousands of bones lie unburied in northern Uganda and South Sudan. How else can we deal with all this and more if we don’t immerse ourselves in art in order to understand the way we are?

The most direct poem I’ve ever written about the role of a poet comes from the very private experience of a “narrator poet” who sees her work as that of providing solace. The poet speaks of what she must do to alleviate the loneliness of a person she knows. The poet is a woman, a friend and lover. The poem remains a space in which fiction and fact trade spaces, feeling right and intimate, or distantly rational and strange. Recently, I wore a wide smile when I got a cheque for a small scholarship from my university. It was enough to pay some bills, do groceries and buy some school supplies. It read: One Thousand Four Hundred and Seventy Eight Dollars and Seventy One cents.

. . . . .

Audrey Lorde and Essex Hemphill: Mothers and Fathers

Posted: June 18, 2013 Filed under: Audre Lorde, English, Essex Hemphill Comments Off on Audrey Lorde and Essex Hemphill: Mothers and Fathers.

Audre Lorde and Essex Hemphill…

Two Black-American poets: one a New Yorker from Harlem with family roots in Grenada and Barbados, the other growing up in Washington D.C. with roots in Columbia, South Carolina; one a passionately political Lesbian with children, the other a passionately political Gay man who would die of complications from AIDS. Both of these writers, in poems and essays combining clear thinking with deep feeling – and in the facts of their lived lives – sought to widen what later came to be known as “identity politics”. Their work goes far beyond it, establishing a universality of truth. In the poems below Lorde and Hemphill reflect upon the meaning of relationship (and sometimes the lack thereof) with their mothers and fathers. These are poems of great intimacy and intelligence with head and heart in thrilling unison.

.

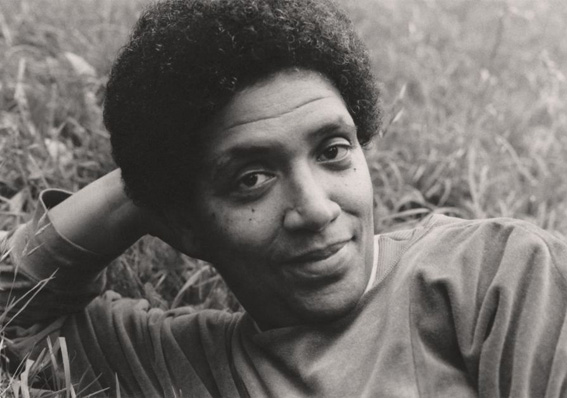

Audre Lorde in Berlin_1984_photograph © Dagmar Schultz

Audre Lorde in Berlin_1984_photograph © Dagmar Schultz

.

Audre Lorde (1934 – 1992)

“Legacy – Hers”

.

When love leaps from my mouth

cadenced in that Grenada wisdom

upon which I first made holy war

then I must reassess

all my mother’s words

or every path I cherish.

.

Like everything else I learned from Linda*

this message hurtles across still uncalm air

silent tumultuous freed water

descending an imperfect drain.

.

I learn how to die from your many examples

cracking the code of your living

heroisms collusions invisibilities

constructing my own

book of your last hours

how we tried to connect

in that bland spotless room

one bright Black woman

to another bred for endurance

for battle

.

island women make good wives

whatever happens they’ve seen worse…

.

your last word to me was wonderful

and I am still seeking the rest

of that terrible acrostic

.

(from Lorde’s collection The Marvelous Arithmetics of Distance, 1993)

*Linda was the name of Lorde’s mother.

. . .

Audre Lorde

“Father Son and Holy Ghost”

.

I have not ever seen my father’s grave.

.

Not that his judgement eyes have been

forgotten

nor his great hands’ print

on our evening doorknobs

one half turn each night

and he would come

drabbled with the world’s business

massive and silent as the whole day’s wish

ready to redefine each of our shapes –

but that now the evening doorknobs wait

and do not recognize us as we pass.

.

Each week a different woman –

regular as his one quick glass each evening –

pulls up the grass his stillness grows

calling it week. Each week

A different woman has my mother’s face

and he, who time has,

changeless.

must be amazed

who knew and loved but one.

.

My father died in silence, loving creation

and well-defined response.

He lived

still judgements on familiar things

and died

knowing a January 15th that year me.

.

Lest I go into dust

I have not ever seen my father’s grave.

.

(1968, revised 1976)

. . .

Audre Lorde

“Inheritance – His”

.

I

.

My face resembles your face

less and less each day. When I was young

no one mistook whose child I was.

Features build colouring

alone among my creamy fine-boned sisters

marked me *Byron’s daughter.

.

No sun set when you died, but a door

opened onto my mother. After you left

she grieved her crumpled world aloft

an iron fist sweated with business symbols

a printed blotter. dwell in a house of Lord’s

your hollow voice chanting down a hospital corridor

yea, though I walk through the valley

of the shadow of death

I will fear no evil.

.

II

.

I rummage through the deaths you lived

swaying on a bridge of question.

At seven in Barbados

dropped into your unknown father’s life

your courage vault from his tailor’s table

back to the sea

Did the Grenada treeferns sing

your 15th summer as you jumped ship

to seek your mother

finding her too late

surrounded with new sons?

.

Who did you bury to become enforcer of the law

the handsome legend

before whose raised arm even trees wept

a man of deep and wordless passion

who wanted sons and got five girls?

You left the first two scratching in a treefern’s shade

the youngest is a renegade poet

searching for your answer in my blood.

.

My mother’s Grenville tales

spin through early summer evenings.

But you refused to speak of home

of stepping proud Black and penniless

into this land where only white men

ruled by money. How you laboured

in the docks of the Hotel Astor

your bright wife a chambermaid upstairs

welded love and survival to ambition

as the land of promise withered

crashed the hotel closed

and you peddle dawn-bought apples

from a pushcart on Broadway.

Does an image of return

wealthy and triumphant

warm your chilblained fingers

as you count coins in the Manhattan snow

or is it only Linda

who dreams of home?

.

When my mother’s first-born cries for milk

in the brutal city winter

do the faces of your other daughters dim

like the image of the treeferned yard

where a dark girl first cooked for you

and her ash heap still smells curry?

.

III

.

Did the secret of my sisters steal your tongue

like I stole money from your midnight pockets

stubborn and quaking

as you threaten to shoot me if I am the one?

the naked lightbulbs in our kitchen ceiling

glint off your service revolver

as you load whispering.

.

Did two little dark girls in Grenada

dart like flying fish

between your averred eyes

and my pajama-less body

our last adolescent summer

eavesdropped orations

to your shaving mirror

our most intense conversations

were you practising how to tell me

of my twin sisters abandoned

as you had been abandoned

by another Black woman seeking

her fortune Grenada Barbados

Panama Grenada.

New York City.

.

IV

.

You bought old books at auction

for my unlanguaged world

gave me your idols Marcus Garvey Citizen Kane

and morsels from your dinner place

when I was seven.

I owe you my Dahomeyan jaw

the free high school for gifted girls

no one else thought I should attend

and the darkness that we share.

Our deepest bonds remain

the mirror and the gun.

.

V

.

An elderly Black judge

known for his way with women

visits this island where I live

shakes my hand, smiling

“I knew your father,” he says

“quite a man!” Smiles again.

I flinch at his raised eyebrow.

A long-gone woman’s voice

lashes out at me in parting

“You will never be satisfied

until you have the whole world

in your bed!”

.

Now I am older than you were when you died

overwork and silence exploding in your brain.

You are gradually receding from my face.

Who were you outside the 23rd Psalm?

Knowing so little

how did I become so much

like you?

.

Your hunger for rectitude

blossoms into rage

the hot tears of mourning

never shed for you before

your twisted measurements

the agony of denial

the power of unshared secrets.

.

(Written January – September 1992. From Lorde’s The Marvelous Arithmetics of Distance)

*Byron was the name of Lorde’s father.

. . . . .

.

Essex Hemphill (1957 – 1995)

“The Father, Son, and Unholy Ghosts”

.

We are not always

the bravest sons

our fathers dream.

Nor do they always

dream of us.

We don’t always

recognize him

if we have never

seen his face.

We are suspicious

of strangers.

Question:

is he the one?

.

I stand waist deep

in the decadence of forgetting.

The vain act of looking the other way.

Insisting there can be peace

and fecundity without confrontation.

The nagging question of blood hounds me.

How do I honour it?

.

I don’t understand

our choice of angers,

your domestic violence,

my flaring temper.

I wanted tenderness

to belong to us

more than food or money.

The ghost of my wants

is many things:

lover, guardian angel,

key to our secrets,

the dogs we let sleep.

The rhythm of silence

we do not disturb.

.

I circle questions of blood.

I give a fierce fire dance.

The flames call me.

It is safe. I leap

unprepared to be brave. I surrender

more frightened of being alone.

I have to do this

to stay alive.

To be acknowledged.

Fire calls. I slither

to the flames

to become birth.

.

A black hole, gaseous,

blisters around its edge,

swallows our estranged years.

They will never return

except as frightening remembrances

when we are locked in closets

and cannot breathe or scream.

I want to be free, daddy,

of the black hole between us.

The typical black hole.

If we let it be

it will widen enough

to swallow us.

Won’t it?

.

In my loneliest gestures

learning to live

with less is less.

I forestalled my destiny.

I never wanted

to be your son.

You never

made the choice

to be my father.

What we have learned

from no text book:

is how to live without

one another.

How to evade the stainless truth.

Drug pain bleary-eyed.

Harmless.

Store our waste in tombs

beneath the heart,

knowing at any moment

it could leak out.

And do we expect to survive?

What are we prepared for?

Trenched off.

Communications down.

Angry in alien tongues.

We use extreme weapons

to ward off one another.

Some nights, our opposing reports

are heard as we dream.

Silence is the deadliest weapon.

We both use it.

Precisely. Often.

.

(1987)

. . .

“In the Life”

.

Mother, do you know

I roam alone at night?

I wear colognes,

tight pants, and

chains of gold,

as I search

for men willing

to come back

to candlelight.

.

I’m not scared of these men

though some are killers

of sons like me. I learned

there is no tender mercy

for men of colour,

for sons who love men

like me.

.

Do not feel shame for how I live.

I chose this tribe

of warriors and outlaws.

Do not feel you failed

some test of motherhood.

My life has borne fruit

no woman could have given me

anyway.

.

If one of these thick-lipped,

wet, black nights

while I’m out walking,

I find freedom in this village.

If I can take it with my tribe

I’ll bring you here.

And you will never notice

the absence of rice

and bridesmaids.

.

(1986)

. . .

Audre Lorde poems © The Audre Lorde Estate

Essex Hemphill poems © Cleiss Press

. . . . .

“And Don’t Think I Won’t Be Waiting”: Love poems by Audre Lorde

Posted: June 18, 2013 Filed under: Audre Lorde, English Comments Off on “And Don’t Think I Won’t Be Waiting”: Love poems by Audre Lorde ZP_Solar Abstract_© photographer Wilda Gerideau-Squires

ZP_Solar Abstract_© photographer Wilda Gerideau-Squires

Audre Lorde (1934 – 1992)

“Pirouette”

.

I saw

your hands on my lips like blind needles

blunted

from sewing up stone

and

where are you from

you said

your hands reading over my lips for

some road through uncertain night

for your feet to examine home

where are you from

you said

your hands

on my lips like thunder

promising rain

.

a land where all lovers are mute.

.

And

why are you weeping

you said

your hands in my doorway like rainbows

following rain

why are you weeping?

.

I am come home.

.

(1968, revised 1976)

. . .

“Bridge through My Window”

.

In curve scooped out and necklaced with light

burst pearls stream down my out-stretched arms to earth.

Oh bridge my sister bless me before I sleep

the wild air is lengthening

and I am tried beyond strength or bearing

over water.

.

Love, we are both shorelines

a left country

where time suffices

and the right land

where pearls roll into earth and spring up day.

joined, our bodies have passage into one

without merging

as this slim necklace is anchored into night.

.

And while the we conspires

to make secret its two eyes

we search the other shore

for some crossing home.

.

(1968, revised 1976)

. . .

“Conversations in Crisis”

.

I speak to you as a friend speaks

or a true lover

not out of friendship nor love

but for a clear meeting

of self upon self

in sight of our hearth

but without fire.

.

I cherish your words that ring

like late summer thunders

to sing without octave

and fade, having spoken the season.

But I hear the false heat of this voice

as it dries up the sides of your words

coaxing melodies from your tongue

and this curled music is treason.

.

Must I die in your fever –

or, as the flames wax, take cover

in your heart’s culverts

crouched like a stranger

under the scorched leaves of your other burnt loves

until the storm passes over?

.

(1970, revised 1976)

. . .

“Recreation”

.

Coming together

it is easier to work

after our bodies

meet

paper and pen

neither care nor profit

whether we write or not

but as your body moves

under my hands

charged and waiting

we cut the leash

you create me against your thighs

hilly with images

moving through our word countries

my body

writes into your flesh

the poem

you make of me.

.

Touching you I catch midnight

as moon fires set in my throat

I love you flesh into blossom

I made you

and take you made

into me.

.

(1978)

. . .

“And Don’t Think I Won’t Be Waiting”

.

I am supposed to say

it doesn’t matter look me up some

time when you’re in my neighbourhood

needing

a drink or some books good talk

a quick dip before lunch –

but I never was one

for losing

what I couldn’t afford

from the beginning

your richness made my heart

burn like a roman candle.

.

Now I don’t mind

your hand on my face like fire

like a slap

turned inside out

quick as a caress

but I’m warning you

this time

you will not slip away

under a covering cloud

of my tears.

.

(1974)

. . . . .

Melvin Dixon as translator: a handful of “love letter” poems by Léopold Sédar Senghor

Posted: June 18, 2013 Filed under: English, French, Léopold Sédar Senghor Comments Off on Melvin Dixon as translator: a handful of “love letter” poems by Léopold Sédar Senghor Melvin Dixon in 1988_photograph from the collection of the New York Public Library

Melvin Dixon in 1988_photograph from the collection of the New York Public Library

.

Léopold Sédar Senghor (1906 – 2001)

“What are you doing?”

.

“What are you doing? What are you thinking about? And of whom?”

This is your question and yours alone.

.

Nothing is more melodious than the one-hundred-metre runner

Whose arms and long legs are pistons of polished olive.

.

Nothing is more solid than the nude bust in the triangular

Harmony of Kaya-Magan flashing his thunderous charm.

.

If I swim like a dolphin in the South Wind,

If I walk in the sand like a dromedary, it is for you.

.

I am not the king of Ghana, or a hundred-metre runner.

Then will you still write to me, “What are you doing?”…

.

For I am not thinking – my eyes drink the blue rhythmically –

Except of you, like the wild black duck with the white belly.

. . .

“Que fais tu?”

.

“Que fais tu? A quoi penses-tu? A qui?”

C’est ta question et ta question.

Rien n’est plus mélodieux que le coureur de cent mètres

Que les bras et les jambes longues, comme les pistons d’olive polis.

.

Rien n’est plus stable que le buste nu, triangle harmonie du Kaya-Magan

Et décochant le charme de sa foudre.

.

Si je nage comme le dauphin, debout le Vent du Sud

C’est pour toi si je marche dans le sable, comme le dromadaire.

.

Je ne suis pas roi du Ghana, ni coureur de cent mètres.

Or tu ne m’écriras plus “Que fais tu?”…

.

Car je ne pense pas, mes yeux boivent le bleu, rythmiques

Sinon à toi, comme le noir canard sauvage au ventre blanc.

. . .

“Your letter on the bed”

.

Your letter on the bed and under the fragrant lamp,

Blue as the new shirt the young man smooths out as he hums,

Like the sky and sea, and my dream your letter.

And the sea has its salt, and air has milk, bread, rice,

I mean its salt. Life contains its sap and the earth

Its meaning. God’s meaning and movements.

Without your letter, life would not be life,

Your lips, my salt and sun, my fresh air and my snow.

. . .

“Ta lettre sur le drap”

.

Ta lettre sur le drap, sous la lampe odorante

Bleue comme la chemise neuve que lisse le jeune homme

En chantonnant, comme le ciel et la mer et mon rêve

Ta letter. Et la mer a son sel, et l’air le lait le pain le riz,

Je dis son sel.

La vie contient sa sève, et la terre son sens

Le sens de Dieu et son mouvement.

Ta lettre sans quoi la vie ne serait pas vie

Tes lèvres mon sel mon soleil, mon air frais et ma neige.

. . .

“My greeting”

.

My greeting is like a clear wing

To tell you this:

At the end of the first sleep, after reading your letter,

In the shadows and swamps, at the bottom of the poto-poto of anguish

And impasse, in the rolling stream of my dead dreams,

Like heads of children in the lost River,

I had only three choices: work, debauchery, or suicide.

.

I chose a fourth, to drink your eyes as I remember them

The golden sun on the white dew, my tender lawn.

.

Guess why I don’t know why.

. . .

“Mon salut”

.

Mon salut comme une aile claire

Pour te dire ceci:

A la fin du premier sommeil, après ta lettre, dans la ténèbre et le poto-poto

Au fond des fondrières des angoisses des impasses, dans le courant roulant

Des rêves morts, comme des têtes d’enfants le Fleuve perdu

Je n’avais que trois choix: le travail la débauche ou le suicide.

.

J’ai choisi quatrième, de boire tes yeux souvenir

Soleil d’or sur la rosée blanche, mon gazon tendre.

.

Devine pourquoi je ne sais pourquoi.

. . .

“The new sun greets me”

.

The new sun greets me on my bed,

The light of your letter and all the morning sounds,

The metallic cries of blackbirds, the gonolek bells,

Your smile on the lawn, on the splendid dew.

.

In the innocent light thousands of dragonflies

And crickets, like huge bees with golden-black wings

And like helicopters turning gracefully and calmly

On the limpid beach, the gold and black Tramiae basilares,

I say the dance of the princesses of Mali.

.

Here I am looking for you on the trail of tiger cats

Your scent always your scent, more exalting than the smell

Of lilies lifting from the bush humming with thorns.

Your fragrant neck guides me, your scent aroused by Africa

When my shepherd feet trample the wild mint.

At the end of the test and the season, at the bottom

Of the gulf, God! may I find again your voice

And your fragrance of vibrating light.

. . .

“Le salut du jeune soleil”

.

Le salut du jeune soleil

Sur mon lit, la lumière de ta lettre

Tous les bruits que fusent du matin

Les cris métalliques des merles, les clochettes des gonoleks

Ton sourire sur le gazon, sur la rosée splendide.

.

Dans la lumière innocente, des milliers de libellules

Des frisselants, comme de grandes abeilles d’or ailes noires

Et comme des hélicoptères aux virages de grâce et de douceur

Sur la plage limpide, or et noir les Tramiae basilares

Je dis la danse des princesses du Mali.

.

Me voici à ta quête, sur le sentier des chats-tigres.

Ton parfum toujours ton parfum, de la brousse bourdonnant des buissons

Plus exaltant que l’odeur du lys dans sa surrection.

Me guide ta gorge odorante, ton parfum levé par l’Afrique

Quand sous mes pieds de berger, je foule les menthes sauvages.

Au bout de l’épreuve et de la saison, au fond du gouffre

Dieu! que je te retrouve, retrouve ta voix, ta fragrance de lumière vibrante.

.

Kaya-Magan – one of the emperor’s titles in an old dynasty of Mali

poto-poto – “mud”, in the Wolof language

gonolek – a bird common to Senegal

. . . . .

The above poems first appeared in Senghor’s Lettres d’Hivernage (Letters in the Season of Hivernage), published in 1972. They were written during brief quiet moments alone by a busy middle-aged man who was the first President of the new Republic of Senegal (1960 to 1980) but who’d also been a poet in print since 1945 (Chants d’Ombre/Shadow Songs). The poems are addressed to Senghor’s second wife, Colette Hubert; the couple was often apart for weeks at a time.

.

Melvin Dixon (1950 to 1992) was an American novelist, poet, and Literature professor. He translated from French into English the bulk of Senghor’s poetic oeuvre, including “lost” poems, and this work was published in 1991 as The Collected Poetry by Léopold Sédar Senghor. Justin A. Joyce and Dwight A. McBride, editors of A Melvin Dixon Critical Reader (2006), have written of Dixon: “Over the course of his brief career he became an important critical voice for African-American scholarship as well as a widely read chronicler of the African-American gay experience.” They also noted Dixon’s ability to “synthesize criticism, activism, and art.” His poetry collections included Change of Territory (1983) and Love’s Instruments (1995, posthumous) and his novels: Trouble the Water (1989) and Vanishing Rooms (1990).

In his Introduction to his volume of Senghor’s Collected Poetry Dixon writes: “Translating Senghor has provided an opportunity for me to bring together much of what I have learned over the years about francophone literature and how my own poetry has been inspired in part by the geography and history of Senegal.”

. . . . .

Melvin Dixon as poet: AIDS, Love, Community

Posted: June 18, 2013 Filed under: English, Melvin Dixon Comments Off on Melvin Dixon as poet: AIDS, Love, Community

ZP_Phill Wilson, now a Thriver_HIV positive for more than a generation_Activist and founder of The Black AIDS Institute

.

Melvin Dixon (1950 – 1992)

“One by One”

They won’t go when I go. (Stevie Wonder)

Live bravely in the hurt of light. (C.H.R.)

.

The children in the life:

Another telephone call. Another man gone.

How many pages are left in my diary?

Do I have enough pencils? Enough ink?

I count on my fingers and toes the past kisses,

the incubating years, the months ahead.

.

Thousands. Many thousands.

Many thousands gone.

.

I have no use for numbers beyond this one *,

one man, one face, one torso

curled into mine for the ease of sleep.

We love without mercy,

We live bravely in the light.

.

Thousands. Many thousands.

.

Chile, I knew he was funny, one of the children,

a member of the church, a friend of Dorothy’s.

.

He knew the Websters pretty well, too.

Girlfriend, he was real.

Remember we used to sit up in my house

pouring tea, dropping beads,

dishing this one and that one?

.

You got any T-cells left?

The singularity of death. The mourning thousands.

It begins with one and grows by one

and one and one and one

until there’s no one left to count.

.

* this one – Dixon’s lover, Richard Horovitz

. . .

“Heartbeats”

.

Work out. Ten laps.

Chin ups. Look good.

.

Steam room. Dress warm.

Call home. Fresh air.

.

Eat right. Rest well.

Sweetheart. Safe sex.

.

Sore throat. Long flu.

Hard nodes. Beware.

.

Test blood. Count cells.

Reds thin. Whites low.

.

Dress warm. Eat well.

Short breath. Fatigue.

.

Night sweats. Dry cough.

Loose stools. Weight loss.

.

Get mad. Fight back.

Call home. Rest well.

.

Don’t cry. Take charge.

No sex. Eat right.

.

Call home. Talk slow.

Chin up. No air.

.

Arms wide. Nodes hard.

Cough dry. Hold on.

.

Mouth wide. Drink this.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

.

No air. Breathe in.

Breathe in. No air.

.

Black out. White rooms.

Head out. Feet cold.

.

No work. Eat right.

CAT scan. Chin up.

.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

No air. No air.

.

Thin blood. Sore lungs.

Mouth dry. Mind gone.

.

Six months? Three weeks?

Can’t eat. No air.

.

Today? Tonight?

It waits. For me.

.

Sweet heart. Don’t stop.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

. . .

“Turning 40 in the ’90s”

.

April 1990

.

We promised to grow old together, our dream

since years ago when we began

to celebrate our common tenderness

and touch. So here we are:

.

Dry, ashy skin, falling hair, losing breath

at the top of the stairs, forgetting things.

Vials of Septra and AZT line the bedroom dresser

like a boy’s toy army poised for attack –

your red, my blue, and the casualties are real.

.

Now the dimming in your man’s eyes and mine.

Our bones ache as the muscles dissolve,

exposing the fragile gates of ribs, our last defense.

And we calculate pensions and premiums.

You are not yet forty-five, and I

not yet forty, but neither of us for long.

.

No senior discounts here, so we clip coupons

like squirrels in late November, foraging

each remaining month or week, day or hour.

We hold together against the throb and jab

of yet another bone from out of nowhere poking through.

You grip the walker and I hobble with a cane.

Two witnesses for our bent generation.

. . .

“Aunt Ida pieces a Quilt”

.

They brought me some of his clothes. The hospital gown.

Those too-tight dungarees, his blue choir robe

with the gold sash. How that boy could sing!

His favourite colour in a necktie. A Sunday shirt.

What I’m gonna do with all this stuff?

I can remember Junie without this business.

My niece Francine say they quilting all over the country.

So many good boys like her boy, gone.

At my age I ain’t studying no needle and thread.

My eyes ain’t so good now and my fingers lock in a fist,

they so eaten up with arthritis. This old back

don’t take kindly to bending over a frame no more.

Francine say ain’t I a mess carrying on like this.

I could make two quilts the time I spend running my mouth.

Just cut his name out the cloths, stitch something nice

about him. Something to bring him back. You can do it,

Francine say. Best sewing our family ever had.

Quilting ain’t that easy, I say. Never was easy.

Y’all got to help me remember him good.

Most of my quilts was made down South. My Mama

and my Mama’s Mama taught me. Popped me on the tail

if I missed a stitch or threw the pattern out of line.

I did “Bright Star” and “Lonesome Square” and “Rally Round,”

what many folks don’t bother with nowadays. Then Elmo and me

married and came North where the cold in Connecticut

cuts you like a knife. We was warm, though.

We had sackcloth and calico and cotton. 100% pure.

What they got now but polyester-rayon. Factory made.

Let me tell you something. In all my quilts there’s a secret

nobody knows. Every last one of them got my name Ida

stitched on the backside in red thread.

That’s where Junie got his flair. Don’t let anybody fool you.

When he got the Youth Choir standing up and singing

the whole church would rock. He’d throw up his hands

from them wide blue sleeves and the church would hush

right down to the funeral parlour fans whisking the air.

He’d toss his head back and holler and we’d all cry Holy.

And never mind his too-tight dungarees.

I caught him switching down the street one Saturday night,

and I seen him more than once. I said, Junie,

You ain’t got to let the whole world know your business.

Who cared where he went when he wanted to have fun?

He’d be singing his heart out come Sunday morning.

When Francine say she gonna hang this quilt in the church

I like to fall out. A quilt ain’t no show piece,

it’s to keep you warm. Francine say it can do both.

Now I ain’t so old fashioned I can’t change,

but I made Francine come over and bring her daughter

Belinda. We cut and tacked his name, JUNIE.

Just plain and simple. “JUNIE, our boy.”

Cut the J in blue, the U in gold. N in dungarees

just as tight as you please. The I from the hospital gown

and the white shirt he wore First Sunday. Belinda

put the necktie E in the cross stitch I showed her.

Wouldn’t you know we got to talking about Junie.

We could smell him in the cloth.

Underarm. Afro-Sheen pomade. Gravy stains.

I forgot all about my arthritis.

When Francine left me to finish up, I swear

I heard Junie giggling right along with me

as I stitched Ida on the backside in red thread.

Francine say she gonna send this quilt to Washington

like folks doing from all across the country,

so many good people gone. Babies, mothers, fathers,

and boys like our Junie. Francine say

they gonna piece this quilt to another one,

another name and another patch

all in a larger quilt getting larger and larger.

Maybe we all like that, patches waiting to be pieced.

Well, I don’t know about Washington.

We need Junie here with us. And Maxine,

she cousin May’s husband’s sister’s people,

she having a baby and here comes winter already.

The cold cutting like knives. Now where did I put that needle?

. . .

The poems above are from Melvin Dixon’s posthumously-published poetry collection, Love’s Instruments (1995) © Faith Childs Literary Agency

.

When He calls me, I will answer…I’ll be somewhere, I’ll be somewhere…

I’ll be somewhere Listening for My Name.

These are words from a Gospel hymn that Melvin Dixon (see the ZP Senghor post immediately above this one for Dixon’s biographical details) quoted when he delivered a speech to The Third National Lesbian and Gay Writers Conference – “OutWrite 92” – in Boston, Massachusetts. That was in 1992, and Dixon hadn’t long to live – AIDS would soon carry him off. He urged those in attendance to “guard against the erasure of our experience and our lives. As white gays become more and more prominent – and acceptable to mainstream society – they project a racially exclusive image of gay reality…(And) as white gays deny multiculturalism among gays, so too do black communities deny multisexualism among their members. Against this double cremation, we must leave the legacy of our writing and our perspectives on gay and straight experiences. Our voice is our weapon…We alone are responsible for the preservation and future of our literature.”

Dixon’s opening remarks are worth quoting at length; they evoke the battle scars of that first brutal decade of AIDS and also demonstrate Dixon’s absolute integrity in acknowledging the interwoven-ness of sexuality and race. Society’s attitude towards AIDS and HIV has evolved somewhat since 1992 but none of that progress came easily; it was the result of courageous and dedicated activism. (Note the un-reclaimed use of the word “nigger” (still, in fact, a lightning-rod word in 2013) and the complete absence of the word “queer” – a hateful slur that was still in popular use by ‘polite’ homophobes in place of the coarser “faggot”):

Melvin Dixon:

“As gay men and lesbians, we are the sexual niggers of our society. Some of you may have never before been treated like a second-class, disposable citizen. Some of you have felt a certain privilege and protection in being white, which is not to say that others are accustomed to or have accepted being racial niggers, and feel less alienated. Since I have never encountered a person of no colour, I assume that we are all persons of colour. Like fashion victims, though, we are led to believe that some colours have been so endowed with universality and desirability that the colour hardly seems to exist at all – except, of course, to those who are of a different colour and pushed outside the rainbow. My own fantasy is to be locked inside a Benetton ad.

No one dares call us sexual niggers, at least not to our faces. But the epithets can be devastating or entertaining: we are faggots and dykes, sissies and bulldaggers. We are funny, sensitive, Miss Thing, friends of Dorothy, or men with ‘a little sugar in the blood’, and we call ourselves what we will. As an anthropologist/linguist friend of mine calls me in one breath: “Miss Lady Sister Woman Honey Girl Child.” Within this environment of sexual and racial niggerdom, recovery isn’t easy. Sometimes it is like trying to fit a size-12 basketball player’s foot into one of Imelda Marcos’ pumps. The colour might be right, but the shoe still pinches. Or, for the more fashionable lesbians in the audience, lacing up those combat boots only to have extra eyelets staring you in the face – and you feel like Olive Oyl gone trucking after Minnie Mouse.

As for me, I’ve become an acronym queen: BGM ISO same or other. HIV plus or minus. CMV, PCP, MAI, AZT, ddl, ddC. Your prescription gets mine.

Remember those great nocturnal emissions of your adolescent years? They told us we were men, and the gooey stuff proved it. Now, in the 1990s, our nocturnal emissions are night sweats, inspiring fear, telling us we are mortal and sick, and that time is running out…I come to you bearing witness of a broken heart; I come to you bearing witness to a broken body – but a witness to an unbroken spirit. Perhaps it is only to you that such witness can be brought and its jagged edges softened a bit and made meaningful…We are facing the loss of our entire generation…(gay men lost to AIDS.) What kind of witness will You bear? What truth-telling are you brave enough to utter and endure the consequences of your unpopular message?”

“Baby, I’m for real”: Black-American Gay poets from a generation ago

Posted: June 18, 2013 Filed under: Don Charles, English, Lamont B. Steptoe, Steve Langley | Tags: Black gay poets Comments Off on “Baby, I’m for real”: Black-American Gay poets from a generation ago. . .

“I dream of Black men loving and supporting other Black men, and relieving Black women from the role of primary nurturers in our community. I dream, too, that as we receive more of what we want from each other that our special anger reserved for Black women will disappear. For too long we expected from Black women that which we could only obtain from other men. I dare myself to dream.”

Joseph Fairchild Beam (1954 – 1988) from Brother to Brother: Words from the Heart, a passionate 1984 essay directed at all – not just gay – Black men

. . .

Lamont B. Steptoe (born 1949)

“Maybelle’s boy”

.

I get from other men

what my daddy never gave

He just left me a house

full of lonesome rooms

and slipped on in his grave.

.

Now

when muscled arms enfold me

A peace descends from above

Someone is holdin’ Maybelle’s boy

and whisperin’ words of love.

. . .

Don Charles (born 1960)

“Comfort”

.

When you looked and

saw my Brown skin

Didn’t it make you

feel comfortable?

.

Didn’t you remember that

old blanket

You used to wrap up in

when the nights got cold?

.

Didn’t you think about that

maplewood table

Where you used to sit and

write letters to your daddy?

.

Didn’t you almost taste that

sweet gingerbread