Sunqupa Harawinkuna / Poemas de amor en la lengua quechua – de un poemario por Lily Flores Palomino / K’ancharina

Posted: February 14, 2013 Filed under: Lily Flores Palomino / K'ancharina, Poemas de amor en la lengua quechua: Lily Flores Palomino, Quechua, Spanish | Tags: Poemas de Amor Comments Off on Sunqupa Harawinkuna / Poemas de amor en la lengua quechua – de un poemario por Lily Flores Palomino / K’ancharinaLily Flores ( nace 1937, Abancay, Apurimac, Perú )

La primera poetisa que escribó junto en quechua y español, dijo La Sra. Flores Palomino/K’ancharina en el año 2009:

“Sigo escribiendo en idioma incaico – mi pluma es pionera e inagotable en quechua.”

.

Dos poemas de amor – del poemario “Troj de poemas queshua-castellano” (1971):

“Khuyay”

.

Taki hina kusi, ratu pasaj

t’ika hina, hajchirimuj mana tupaykuna

samp’a weqe hina, tuyturimuj

tukuy atij, hatun Apu hina.

.

Khuyayaqa muspha muspha kausaymi,

rijchasqapas puñasqapas mosqoqakuymi

khuyayaqa asirikuspa wañuymi

manachayqa, killkakunawan tipasqapas wañuytajmi.

.

Khuyayqa takin, hajchirimuj t’ikapiwan

hinallatajmi, sumaj qapaj ancha kusipas

phajchirimuspa tukukuypas khuyayllatajmi

hinallatajmi ñakarispa wañuypas.

.

Khuyayqa apukunatapas umanchaymi

llullulla sumaj q’apariytajmi

ancha nanachikuypas waspirichiymi

wañuypas, sami kaypas, khuyayllatajmi.

. . .

“Amar”

.

Alegre y fugaz cual canto

radiante y sensible como flor,

frágil y quebrantoso cual llanto

poderoso y supremo como Dios.

.

Amar, es vivir delirante

soñar despierto o dormido,

amar, es morir sonriente

o es morir enclavado.

.

Canto, flor radiante es amar,

perfumes y aleluya lo es también,

fragmentarse y morir es amar,

Calvario y muerte lo es también.

.

Amar es bendecir a Dios

lo es, bálsamo de ternura,

amar, es blasfemia a Dios

o es vapor de amargura,

Gloria o muerte es amar.

. . .

”Munakusqaymi Kanki”

.

Llakiy thanichij

purisqaypi samarinay

waqayniypas thanichij

qaritaj kachi yakutaj.

.

Allin wiraqocha munasqaymi kanki

mana qantaqa, manan pitatas munaymanchu.

.

Yachanin qampa kasqayta

sumajllata llamiyuwajtiki

llanllalla wayrapa ch’allaynikiwan

t’ijrakamuyniki khipuchawajtin

allin qaripa marq’anampas kanman hina.

.

Ñoqataj khuyakuyniywan kutirichiyki

ancha samiraj, qanman qokuspa

phiña phiñaña, churakujtinkupas

uquykipi kay, warmiman rijchajkuna

.

Munakusqaymi kanki, tayta qocha

suyawasqayki hinallapuni suyaykuwanki

ruphapakuyniy thanichiwanaykipaj

qan rayku shayna kasqayta

mancharikuna anqash, ñoqa munakusqay.

“Eres mi Amado”

.

Consuelo de mis penas

refugio en mi andanza

sociego de mi lamento

hombre y salada agua.

.

Arrogante señor, eres mi amante,

no puedo a nadie amar que no seas tú.

.

Siento ser tuya

cuando me dejo acariciar

con tu fresca y suave brisa

cuando tus olas me envuelven

cual brazos fuertes de un gran varón.

.

Yo con ternura te correspondo

cuando feliz me doy a tí

aunque celosas puedan estar

todas las musas que guardas tú.

.

Eres mi amado, inmenso mar.

Espérame siempre como lo haces

para refrescar mi febril estado

sentido por tí

– monstruo azul, amante mío.

. . . . .

Sunqupa Harawinkuna / Poemas del Corazón en el idioma quechua por Kusi Paukar

Posted: February 14, 2013 Filed under: Kusi Paukar, Quechua, Spanish, Sunqupa Harawinkuna por Kusi Paukar | Tags: Poemas de Amor Comments Off on Sunqupa Harawinkuna / Poemas del Corazón en el idioma quechua por Kusi PaukarKusi Paukar (César Augusto Guardia Mayorga)

Sonqup Jarawiinin / El Cantar del Corazón

Sunqupa Harawinkuna / Poemas del Corazón

Lima, Perú, 1961

Traducciones del idioma quechua: Jesús Lara

“Waylluy”

.

¿Imaraq kay waylluy?

Qawaspa mana qawaq,

Munaspa mana munaq,

Maskaspa mana maskaq,

Waylluqtukuspa cheqnichikuq,

Cheqniqtukuspa waylluchikuq

Kay waylluy kasqanta,

Sonqullaymi yachan.

.

“Amor”

.

¿Qué será el amor?

Que mirando no mira,

Que queriendo no quiere,

Que buscando no busca;

Que simulando amar despierta odio,

Que fingiendo odio hace querer

Lo que es el amor,

Sólo mi corazón lo sabe.

. . .

“Qampaq”

.

Umaypim yuyayniiki

Patpatichkan,

Pillpintup rapran jina

Mana samaq.

.

Rinriipim sutiiki

Tuta punchau

Sirwan,

Mana wayrap apasqan

Mana pip uyarisqan.

.

Sonquypim waylluyniiki

Kausan,

Arwi arwi yura jina

Arwiwaspa.

.

Llakispa, asiq tukuni,

Mana pipas llakisqayta

Musianampaq.

Qamllam, sonquypi yachanki,

Imay kusikusqayta,

Jaykaq llakikusqayta,

Cheqampi.

.

“Para Ti”

.

En mi mente

Palpita tu recuerdo,

Como alas de mariposa,

Sin descanso.

.

En mis oídos

Vibra tu nombre

Noche y dia,

Sin que nadie lo oiga,

Sin que se lo lleve el viento.

.

En mi corazón

Vive tu amor,

Aprisionándome

Como enredadera.

.

Sufriendo, simulo reír

Para que nadie

Sospeche siquiera

Que sufro.

Sólo tú sabes en mi corazón

¡Cuándo me alegro en verdad,

Cuándo en verdad sufro!

. . .

“Ama Tapukuychu”

.

Warmita, waytata jina qawaspa,

Manaña puñuyta atipaspa,

¿Imapaqtaq tapukunki

Ima onquy kasqanta?

.

Waylluymi mismichkasunki,

Mana musiasqayki;

Kuyaymi arwichkasunki,

Mana yachasqayki.

.

Ama jampita yanqa maskaychu.

Sonquillampi kausay,

Ñawillampi qawakuy,

Makillampi kay.

Waylluy onquyqa,

Waylluyllawanmi jampikun.

.

“No Preguntes”

.

Cuando mires a la mujer

Como a una flor;

Cuando ya no concilies el sueño,

¿Para qué preguntas

Qué enfermedad sufres?

.

Te está rezumando el amor,

Sin que lo sospeches siquiera;

Te está enredando el cariño

Sin que tú lo sepas.

.

No busques remedio en vano.

Vive en su corazón,

Mírate en sus ojos,

Ponte en sus manos;

Que la enfermedad del amor

Sólo con amor se cura.

. . .

“Walka”

.

Walkam sutin karqa

Ñoqallay kuyachkaptii.

Tuta jina ñawinpas,

Chukchampas tutay tuta.

.

Walkam suntin karqa

Ñoqallay waylluchkaptii.

Yuraq sisa kirumpas,

Qantu qantu siminpas.

.

Walkam sutin karqa

Ñoqallata kuyawachkaptin.

Waqaptimpas

Sacha kuna sullakuq,

Asiptimpas

Pukiukuna asikuq.

.

Walkam sutin karqa

Ñoqallay kuyachkaptii,

Ñoqallata kuyawachkaptin.

Imaraq kunan sutin

Walka sutiyoq warmi.

.

Sutillanñam simiipi,

Ñawillanñam ñawiipi.

Walka sutiyoq urpi.

Imaraq kunan sutin.

.

“Walka”

.

Su nombre era Walka

Cuando yo, solo, la quería.

Como la noche eran sus ojos,

Sus cabellos, más que la noche.

.

Walka era su nombre

Cuando yo, solo, la amaba.

Sus dientes eran como níveas flores,

Sus labios, como las cantutas.

.

Era su nombre Walka

Cuando ella sólo me quería a mí.

Cuando lloraba

De rocíos se cubrían los árboles,

Cuando reía,

Reían también las fuentes.

.

Walka era su nombre

Cuando yo, solo, la quería,

Cuando ella sólo me quería a mí.

¿Qué se llamará ahora

La mujer que se llamaba Walka?

.

Ya sólo su nombre está en mis labios,

Ya sólo sus ojos están en mis ojos.

Paloma: Walka era tu nombre.

¿Qué te llamarás ahora?

. . .

“Kuyaspa”

.

Sonquymi kirisqa kachkan

Ñawiikipa kanchayninwan,

Onquyñam kuyayniiqa,

Wañuymanchus jinam apawanqa.

.

Chisi tuta nuspaspa

Sutiikita oqarisqani

Mana pip uyarisqan,

Ichapas wayra uyarirqa,

¿Maytaraq, yanallay,

Sutiikita wayra aparqa?

.

Ichapas qam kaqpi muyuykachaspa

Llakillayta willasurqanki,

Qamtaq mancharikuspa,

Ayqereqanki.

.

“Quieriendo”

.

Mi corazón está herido

Con la luz de tus ojos,

Ya mi amor es una enfermedad

Que tal vez me lleve a la muerte.

.

Anoche delirando,

Pronuncié tu nombre

Sin que nadie lo oyese.

Acaso lo oyó el viento.

¿A dónde llevaría

Tu nombre el viento,

Amada mía?

.

Quién sabe

Si dando vueltas

En torno tuyo,

Te contó mis penas,

Y tú te asustaste

Y te fuiste.

. . .

“¡Imanaykusaqtaq!”

.

Imanaykusaqtaq kunanqa,

Llakiimi kichka jina

Sonquyta nanachichkan.

.

Imanaykusaqtaq kunanqa,

Yuyayniikim tuta jina

Punchauniita tutayachichkan.

.

Imanaykusaqtaq kunanqa,

Waqayta munaspapas

Weqellaymi mana lloqsinchu.

.

Imanaykusaqtaq kunanqa,

Kayta wakta qawaptiipas,

Manam imatapas rikunichu.

.

Sonqullaymi sapampi,

Imapaqraq pipas maypas,

Mana kuyananta kuyan,

Nispa niwan.

.

“¿Qué voy hacer?

.

¿Qué voy hacer ahora?

Mi pena como una espina

Está hincando mi corazón!

.

¿Qué voy hacer ahora?

¡Tu recuerdo como la noche

Está oscureciendo mi día!

.

¿Qué voy hacer ahora?

¡Hasta cuando quiero llorar

No asoman las lágrimas!

.

¿Qué voy hacer ahora?

¡Hasta cuando quiero mirar

No miro nada!

.

Solo mi corazón en su soledad

Se pregunta a sí mismo:

¿Para qué se amará

Lo que no se debe amar?

. . .

“Auqaypaq”

.

Yuyayniipim yuyayniiki

Patpatichkan,

Tutayaq punchaupi

Urpi patpatichkaq jina.

.

Puchqu yaku jina

Yuyayniiki,

Kausayniita puchquyachichkan

Mana qampa yachasqayki.

.

Musiaspaqa, yachaspaqa,

Warmi sonquyki,

Warmipa kaspapas,

Sinchitachari Llakikunman.

.

Maypiraq, chaypnaq qamqa,

Asikuspa, kusikuspa,

Llakiita mana yachaspa,

Qonqayta munawaspa,

Qonqawaytaña qallaykunki.

.

Mana kuyana auqa,

Manaña kuyayta tarispa,

Manaña sonquyoq,

Pitaraq wayllunki,

Piñaraq kuyasunki.

.

Sapallaykina rikukuspa,

Weqellaykita umikunki,

Sonquykitaq qaparispa,

Waqaya kunan

Nispa nisunki.

.

Mana kuyana auqa,

Manaña sonquyoq,

¿Pitaraq wayllunki?

¿Piñaraq kuyasunki?

.

“Para mi Adversaria”

.

En mi memoria

Tu recuerdo está latiendo

Como aleteo de paloma

En día que anochece.

.

Como agua amarga,

Tu recuerdo

Está amargando mi vida

Sin que tú lo sepas.

.

Si lo supieras,

Si sospecharas siquiera,

Tu corazón de mujer,

Siendo de mujer,

¡Cómo sufriría!

.

¿Dónde estarás tú,

Riendo y gozando

Sin saber mi pena?

Cuando se quiere olvidar,

Ya empieza el olvido.

.

Indigna de ser amada,

Ya sin encontrar cariño,

Ya sin corazón,

¿A quién amarás?

¿Quién te amará?

.

Al verte ya sola

Beberás tus lágrimas,

I el corazón te dirá a gritos:

¡Ahora sólo te resta llorar!

.

Indigna de ser amada,

Ya sin corazón,

¿A quién amarás?

¿Quién te amará?

. . .

“Pituchakuy”

.

Ay ruruchay rurucha,

Ñawi rurucha.

Warmi kasqanta yachachkaspa

Qawarqanki.

.

Ay ruruchay rurucha,

Sonqu rurucha.

Kuyay kasqanta yachachkaspa

Kuyarqanki.

.

Waqayari ñawi,

Llakiyari sonqu,

Chay mana qawana qawasqaykimanta,

Chay mana kuyana kuyasqaykimanta.

“Arrepentimiento”

.

¡Ay! niña de mis ojos.

¡Ay! pupila mía.

Sabiendo que era mujer

La miraste.

.

¡Ay! corazón mío,

Corazón,

Sabiendo lo que es amor,

La amaste.

.

Llora, pues, pupila mía

Por haber mirado

A quien no debiste mirar;

Sufre, pues, corazón,

Por haber amado

A quien no debiste amar.

. . .

“Kaynay”

.

Waylluy, sonquykipi kaptinqa,

Jarawii;

Llaki qasquykita kiriptinqa,

Jarawii, takii, machay;

Auqanayki kaptinqa,

Qari jina kallpachakuspa,

Wajujuy, jayllii.

Cheqnii atisuptiikiqa,

Upallalla kausay,

Ama sonquykita rikchachiichu,

Ama kausayta qanrachaychu.

.

“Has así”

.

Canta,

Si el amor está en tu corazón;

Canta, baila, embriágate,

Si la pena hiere tu pecho.

Si tienes que luchar,

Cobra fuerzas varoniles

Y entona conciones triunfales.

Pero si el odio te domina,

No despiertes a tu corazón,

Vive en silencio,

No ensucies la vida.

. . . . .

Poemas de amor en la lengua quechua – Juan Wallparrimachi, José David Berríos, y unos poetas bolivianos anónimos

Posted: February 14, 2013 Filed under: José David Berríos, Juan Wallparrimachi, Poemas de amor quechua: Juan Wallparrimachi + José David Berríos + unos poetas bolivianos anónimos, Quechua, Spanish | Tags: Poemas de Amor Comments Off on Poemas de amor en la lengua quechua – Juan Wallparrimachi, José David Berríos, y unos poetas bolivianos anónimosPoemas de amor quechua – del siglo IXX: Juan Wallparrimachi, José David Berríos, y unos poetas bolivianos anónimos

.

“Urpi”

.

Munakusqay urpi,

uyaririllaway,

sunquyta paqumaq

munakapullaway.

.

Waqcha ch’ujllitayman

pusakapusqayki,

chaypi wayllususpa

munakamusqayki.

.

Uj wik’uñita

chakupamusqayki,

amapolitaswan

t’ikanchapusqayki.

.

Uj ch’aynitutapis

jap’imullasaqtaq,

misk’I takiyninwan

kusichisunanpaq.

.

Uj ovejitata

jip’ikapusqayki,

panti millmitaswan

chinuykapusqayki.

.

Nuqamin tarpusaq

quyllu papitasta,

qanri misk’ikunki

clavel t’ikitasta.

.

Nuqamari risaq

qaqa patitasta,

apakamusqayki

phasakanitasta.

.

Jakulla ripusun,

urpi munakusaqay,

qanmin yanay kanki

wiñay wayllukusqay.

.

Munanakuspalla

khuska kawsakusun,

t’ikasta rikhuspa

aswan munakusun.

. . .

“Paloma”

.

Mi querida palomita,

escúchame, por favor,

a mi corazón aprisionado

quiéremelo nomás.

.

A mi pobre chocita

te estoy llevando,

allí tiernamente

bien te amaré.

.

Una vicuñita

cazaré para tí

y con amapolitas

te adornaré.

.

También un jilguerito

cogeré para tí,

para que con su dulce trino

te haga alegrar.

.

Una ovejita

te la encerraré,

con su lana suave

bien te arrumaré.

.

También sembraré

papita quyllu,

con florecitas de clavel

tú te perfumarás.

.

Pronto voy a ir

a la punta de la peña

y te traeré

fruto de ulala.

.

Vamos ya, vámonos,

mi querida paloma,

tú serás mi pareja

y te mimaré para siempre.

.

Queriéndonos nomás

viviremos juntos,

mirando las flores

nos amaremos más.

. . .

“K’ita Urpi”

.

Imallataq kay munakuy,

k’ita urpillay,

chiquititan chhika sinchi,

mana khuyana,

ancha yachayniyuqtapis

k’ita urpillay,

muspa muspaspa purichin,

mana khuyana.

.

K’ita urpillay,

mana khuyana,

pacha k’anchiyanna

ripukunallay.

.

Kayraq phawaq waqyanaq

k’ita urpillay.

ñanniykita rikhuchiway,

mana khuyana,

mana pipis musyasqallan,

k’ita urpillay,

kay chhikimanta qhispisaq,

mana khuyana.

. . .

“La paloma agreste”

.

¿Qué viene a ser el amor,

palomita agreste,

tan pequeño y esforzado,

desamorada,

que al sabio más estendido,

palomita agreste,

le hace andar desatinado,

desamorada?

.

Palomita agreste,

desamorada,

amanece el día

en que yo me vaya.

.

Alegre golondrina,

palomita agreste,

enséñame tu camino,

desamorada,

para irme sin que me sientan,

palomita agreste,

y salvarme de mi destino,

desamorada.

. . .

Tres poemas de Juan Wallparrimachi (1793-1814)

“Imaynallatan atiyman”

.

Imaynallatan atiyman

yana ch’hillu chujchaykita

quri ñaqch’awan ñaqch’aspa

kunkaykipi pujllachiyta?

.

Imaynallatan atiyman

ch’aska quyllur ñawiykita

ñawsa kayniyta kichaspa

sunqullaypi k’anchachiyta?

.

Imaynallatan atiyman

puka mullu simiykita

samayniykita umispa

astawanraq phanchachiyta?

.

Imaynallatan atiyman

rit’I sansaq makiykita

jamanq’ayta p’inqachispa

astawanraq sansachiyta?

.

Imaynallatan atiyman

chay sumaq puriyniykita

sapa thaskiypi t’ikata

astawanraq mut’uchiyta?

.

Kay tukuyta atispanari

atiymantaq sunquykita

sunquy chawpipi mallkispa

wiñaypaq phallallachiyta.

. . .

Tres poemas del Soldado-Poeta Juan Wallparrimachi (Macha, Potosí, 1793-1814)

(Traducciones por Jesús Lara)

“¿Cómo pudiera hacer?”

.

¿Cómo pudiera hacer

para peinar con peine de oro

tu negra y encantada cabellera

y ver como ella ondula al redor de tu cuello?

.

¿Cómo pudiera hacer

para que los luceros de tus ojos,

abriendo el caos de mi cegüedad,

sólo brillaran en mi corazón?

.

¿Cómo pudiera hacer

para beber tu aliento y conseguir

que el rojo coral de tus labios

se volviera más bello todavía?

.

¿Cómo pudiera hacer

para que la pureza de tu mano

avergonzando a la azucena

reverberara todavía más?

.

¿Cómo pudiera hacer

para que el ritmo de tu andar

en cada paso fuera derramando

más flores que las que hoy le veo derramar?

.

Y si me fuera dado hacer todo esto,

ya podría plantar tu corazón

dentro del mío, como un árbol,

para verlo

eternamente verdecer.

. . .

“Chay ñawiyki”

.

Chay quyllur ñawiyki uj tuta

llakiyniypi urmaykamurqan.

sunquypi pakaykuq rijtiy

ruruq urpiman tukurqan.

.

Ch’ikikuq muyuq wayrari

qhichuwarqan makiymanta,

ñawiy chakiytan wataspa

mana rinaypaq qhipanta.

.

Ñanpi tukuypa sarusqan,

intiq paraqpa waqtasqan,

ruruq urpinpi yuyaspa

sapallan sunquy mullphasqan.

. . .

“Esos tus ojos”

.

Como una estrella tu pupila

cayó una noche en mi congoja.

Caundo a esconderla fui en mi pecho

se convirtió en tierna paloma.

.

Luego, envidioso torbellino

me la arrebató de las manos,

para evitar que la siguiera

dejome ciego y amarrado.

.

Encarnecido en el camino,

flagelado por lluvia y sol,

pensando en su tierna paloma

se carcome mi corazón.

. . .

“Munarikuway”

.

Qanllapin sunquy,

qantan rikuyki

musquyniypipas.

Qanpin yuyani,

qantan mask’ayki

rijch’ayniypipas.

.

Inti jinamin

ñawiykikuna

ñuqapaq k’anchan.

Ñawraq t’ikari

uyaykipinin

ñuqapaq phanchan.

.

Chay ñawillayki

k’anchaynillanwan

kawsachiwantaq.

Phanchaq simiyki

asikuyninwan

kusichiwantaq.

.

Munakullaway,

irpa urpilla,

mana manchaspa.

Ñuqa qanrayku

wañuy yachasaq

qanta munaspa.

. . .

“Ámame”

.

Sólo en ti está mi corazón

y cuando sueño

no veo a nadie sino a ti.

Sólo en ti pienso

y a ti también te busco

si estoy despierto.

.

Igual que el sol

fulguran para mí

tus ojos.

En tu faz se abren,

para regalo mío,

todas las flores.

.

La lumbre sola

de tus pupilas

me da la vida.

Y tu boca florida

con su sonrisa

me hace dichoso.

.

Ven y ámame,

tierna paloma,

no temas nada.

Pese al destino,

yo te amaré

hasta la muerte.

. . .

“Cochabambamanta arawis”

.

Q’ara panpa sunquykipi

manayniyta tarpurqani,

tipiyniyta uqhariq rispa

khishkaman taripurqani.

.

Uj thapapi uywasqa urpi

lijran pura sawnanasqa,

imaynata qunqawanki

si sunquy qanwan yachasqa?

.

Sayk’usqa monteq chawpinpi

llak’isqa samarikuni

nuqaypa llanthullaywantaq

urpiywan pantachikuni.

.

Munakuyki niwarqanki,

maytaq chay munakuyniyki,

qaqapichu, urqupichu,

mayqin runaq llaqtanpichu?

.

Sunquytachus qhawaykuwaq

yawar qhuchapi wayt’asqan

khiskasmanta jarap’asqa

ayrun ayrunta waqasqan.

.

Nuqa mayu rumi kani

qaqamanta k’aqtikamuq,

sinchiq wayraq rumichisqan

punkuykiman k’umuykamuq.

.

Rikuy pitan munasqani

mana sunqunta yachaspa

nuqallataq mask’akuni

jik’un ji’unta waqaspa.

.

Chujchaykita kachaykamuy

chujchaykipi sipikusaq,

t’inpiykipi wañupusaq,

sunquykipi p’anpakusaq.

.

Para yakuchu kasqani

wayq’un wayq’un purinaypaq?

mamaychu, tataychu kasqa

mana qunqay atinaypaq?

. . .

“De Cochabamba, Coplas amorosas”

.

En el desierto de tu corazón

sembré un día mi amor

y al ir a recoger la cosecha

solamente espinas hallé.

.

Un solo nido tuvimos,

ala con ala dormimos,

¿cómo quieres olvidarme

si mi corazón es tuyo?

.

Cansado, en pleno monte

descanso de mis penas

y mi propria sombre

me hace confundir con mi paloma.

.

Me dijiste que me amabas,

¿dónde está ese tu amor?

en el monte, en las rocas

o en algún país lejano?

.

Si vieras mi corazón

nadando en un lago de sangre,

enmarañado entre espinas

está llorando sin consuelo.

.

Yo soy guijarro del río

desprendido del barranco

que endurecido por el viento

vino a dar a tu puerta.

.

Miren a quién estoy queriendo

sin conocer su corazón,

yo mismo la busco

llorando sin consolación.

.

Entrégame tu cabello,

con él me voy a ahorcar,

en tu regazo voy a morir,

en tu corazón me voy a enterrar.

.

¿Soy agua de lluvia acaso

para errar por las quebradas?

¿Mi padre o mi madre es ella

Que no la pueda olvidar?

José David Berríos (Potosí, Bolivia, 1849-1912)

“Yuyarikuway”

.

Maypachachus lliphipispa

k’anchaq inti kutimunqa

k’illmi tutata ayqichispa,

yuyarikuway.

.

Maypachchus uraniqta

sayk’usqaña wasaykunqa

lawraq phuyu chawpillanpi,

yuyarikuway.

.

Maypachachus uyarinki

urpi sapan rikhukuspa

sach’a chawpipi waqaqta,

yuyarikuway.

.

Janaq pacha chawpimanta

llunp’aq killata rikuspa

tutata sut’iyachiqta,

yuyarikuway.

.

Ñuqaqa paqarimuypi

ch’isiyaypi llakikuspa

qanllawan muspaykachani…

Yuyarikuway.

.

Kay kawsayniy tukukuqtin

chikaykuqtiy jallp’a ukhuman

phutiy phutiyta waqaspa,

yuyarikuway.

.

Chay waqayniyki qarpaqtin

chiri ushpayta phanchimunqa

sunquymanta yuyay t’ika…

Yuyarikuway.

. . .

José David Berríos (Potosí, Bolivia, 1849-1912)

“Acuerdate de mi”

.

Cuando el sol resplandeciente

venga otra vez ahuyentando

a la tenebrosa noche,

acuérdate de mí.

.

Cuando cansado se abisme

tras la línea del poniente

envuelto en ardientes nubes,

acuérdate de mí.

.

Cuando escuches que solloza

su soledad lamentando

la paloma entre los árboles,

acuérdate de mí.

.

Al clarear la mañana

y al anochecer penando

yo sólo sueño contigo…

Acuérdate de mí.

.

Cuando mi vida se acabe

y a la sepultura baje,

en tu tristeza llorando,

acuérdate de mí.

.

Por tus lágrimas regada

brotará de mis cenizas

la tierna flor del recuerdo…

Acuérdate de mí.

. . . . .

Benito de Jesús’ “Nuestro Juramento” (“Our Oath”) as sung by Julio Jaramillo

Posted: February 14, 2013 Filed under: Benito de Jesús, Translator's Whimsy: Song Lyrics / Extravagancia del traductor: Letras de canciones traducidas por Alexander Best, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: Poemas de Amor Comments Off on Benito de Jesús’ “Nuestro Juramento” (“Our Oath”) as sung by Julio Jaramillo

ZP_A vintage Valentine’s Day postcard_1930s?_Note the absence of cutesy sentimentality or smarmy earnestness. Depicted are The Wiles, The Game, of Love.

Anyone hearing the 1957 recording of “Our Oath” (“Nuestro Juramento”) by 22-year-old Julio Jaramillo – later known as “The Nightingale of The Americas” for his sweet high tenor – perhaps will be surprised to learn – once the words have been translated from Spanish into English – how extravagantly Romantic are the lyrics of the song. Benito de Jesús’ lyrics emphasize Death and Love together, and it’s easy to forget that the word Romantic (with a capital R) used to include both – though the saccharine cuteness of Valentine’s Day – with its boxes of chocolates and bouquets of a dozen red roses – has diluted in the public sphere the irrational intensity of that many-limbed emotion, Love. In fact, there is nothing more Romantic than the death of the belovéd. de Jesús’ outlandish – by contemporary standards – and absolutely un-ironic – verses, combined with the delicacy and sincerity of Jaramillo’s voice, make for a curiously disquieting yet moving popular love song.

. . .

Benito de Jesús (1912 – 2010, Puerto-Rican composer)

“Our Oath” (“Nuestro Juramento”)

as sung by Julio Jaramillo (1935 – 1978, Guayaquil, Equador)

Translation/Interpretation from Spanish: Alexander Best

.

“Our Oath”

.

Your sorrowful face

I just cannot look upon

– because it kills me.

.

Sweet darling,

the weeping that

from you spills forth,

with anguish fills my heart.

.

Wordlessly I suffer if sad you fall,

I wish that no doubt might

make you cry at all.

We have vowed to love each other

until the day we die…

And if the dead may love?

– well, after our death we’ll love each other

all the more, oh my!

.

If I die first, promise to let a weeping

that sprouts from sorrow

pour down upon my body dead,

so that your love for me

by everyone present will be read.

.

If you should die first, I promise to write

the story of our love,

full of feeling in my soul.

Yes, I shall write our story in blood

– the ink-blood of my heart –

so that our tale of love is told!

Después de su grabación en 1957, el bolero “Nuestro Juramento”, del compositor puertoriqueño Benito de Jesús, se convertió en icono de la música ecuatoriana. ¿Y por qué? A causa del tenor dulce de un cantante nacido en Guayaquil – Julio Jaramillo. En esta canción extravagante de Amor, Jaramillo – conocido más tarde como El Ruiseñor de América – canta con mucha ternura el tema, y la letra habla de una emoción fuerte que traspasa los límites de la vida. Merece la pena recordar en este Día de San Valentín que no es siempre precioso y meloso el Amor (como chocolates y ramos de rosas). El Amor incluye la eventualidad de un gran Hecho amenazador en el horizante – la Muerte.

. . .

Benito de Jesús (1912 – 2010, compositor puertoriqueño)

“Nuestro Juramento”

cantado por Julio Jaramillo (1935 – 1978, Guayaquil, Equador)

.

No puedo verte triste porque me mata

tu carita de pena, mi dulce amor.

Me duele tanto el llanto que tu derramas,

que se llena de angustia mi corazón.

.

Yo sufro lo indecible si tu entristeces,

no quiero que la duda te haga llorar.

Hemos jurado amarnos hasta la muerte

y si los muertos aman,

después de muertos amarnos más.

.

Si yo muero primero, es tu promesa,

sobre de mi cadaver dejar caer

todo el llanto que brote de tu tristeza

y que todos se enteren de tu querer.

.

Si tú mueres primero, yo te prometo,

escribiré la historia de nuestro amor

con toda el alma llena de sentimiento.

La escribiré con sangre,

con tinta sangre del corazón.

. . . . .

“Orfeu Negro” and the origins of Samba + Wilson Batista’s “Kerchief around my neck” and Noel Rosa’s “Idle youth”

Posted: February 8, 2013 Filed under: English, Noel Rosa, Orfeu Negro and the origins of Samba + Wilson Batista's “Kerchief around my neck” and Noel Rosa's “Idle youth”, Portuguese, Wilson Batista | Tags: Black History Month photographs Comments Off on “Orfeu Negro” and the origins of Samba + Wilson Batista’s “Kerchief around my neck” and Noel Rosa’s “Idle youth”

ZP_Breno Mello, 1931 – 2008, as Orpheus in the 1959 Marcel Camus film, Orfeu Negro_Mello was a soccer player whom Camus chanced to meet on the street in Rio de Janeiro. Camus decided to cast the non-actor as the lead in the film. Mello turned out to be exactly right for the role of the star-crossed Everyman enchanted by tricky Fate – his Love is stalked by Death.

- ZP_Marpessa Dawn, American-born actress of Black and Filipino heritage who played Eurydice opposite Breno Mello as Orpheus in the 1959 film Orfeu Negro. She is seen here in a photograph taken at the 1959 Cannes Film Festival. Dawn would later have a bizarre role as Mama Communa in the often-censored or banned 1974 Canadian film by European director Dusan Makavejev – Sweet Movie. A long way from her role in Orfeu Negro…yet she brought something of her beautiful wholesomeness even to the disturbing scenarios of Sweet Movie. Marpessa Dawn died in 2008 at the age of 74 in Paris.

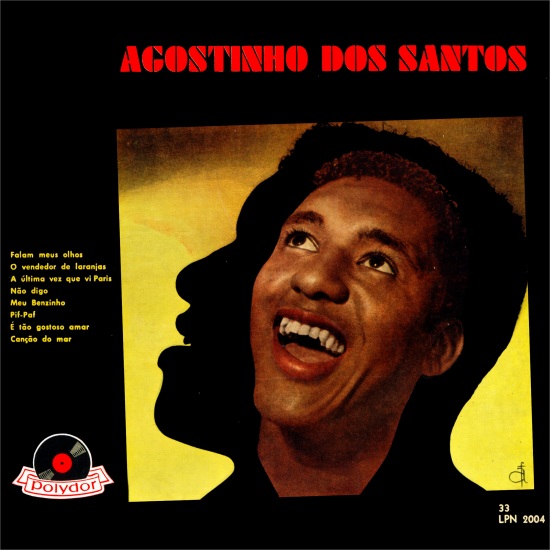

ZP_a 1956 record album by Agostinho Dos Santos who sang the now internationally famous songs from the 1959 film Orfeu Negro_ A Felicidade and Manhã de Carnaval

Orfeu Negro (Black Orpheus), a 1959 film in Portuguese with subtitles, was directed by Marcel Camus in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Set at Carnaval time, it featured a mainly Black cast and told a modern Brazilian version of the Greek legend of Orpheus and Eurydice. The Morro da Babilônia “favela” (Babylon Hill “slum”) was used for filming many scenes. Orfeu Negro is a nearly perfect film. Exuberant and pensive, charming and mysterious, it is an engrossing story of doomed Lovers accompanied by the exquisitely-intimate singing of Agostinho Dos Santos of Luiz Bonfá’s songs in the then-nascent bossa nova style. And add to all that the “crazy Life force” pulse of Samba at night in the streets…

Samba – the word – is derived via Portuguese from the West-African Bantu word “semba”, which means “invoke the spirit of the ancestors”. Originating in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil, by the 1920s the Samba sound was emerging with usually a 2/4 tempo, the use of choruses with hand-claps plus declaratory verses, and much of it in batucada rhythm which included African-influenced percussion such as tamborim, repinique, cuica, pandeiro and reco-reco adding many layers to the music. The “voice” of the cavaquinho (which is like a ukulele) provided a pleasing contrast and a non-stop little wooden whistle, the apito, made the urgent breath of human beings palpable.

In the late 1920s in the Rio favela of Mangueira – among others – there began one of the earliest “samba schools”, initiating the transformation of Rio de Janeiro’s Carnaval (which had existed on and off since the 18th century but which was neither a large city-wide event nor one with a strong Black Brazilian influence). In the 21st century, of course, Carnaval in Rio de Janeiro has become the most massive festival in the world; in 2011, for example, close to 5 million people took part, with more than 400,000 of them being foreign visitors. But back in the 1920s…the original Mangueira cordões or cords (also known as blocos or blocks) consisted of groups of masked participants, all men, who were led down the street by a “teacher” blowing an apito whistle. Following them was a mobile orchestra of percussion. In the years that followed the Carnaval procession expanded to include 1. the participation of women 2. floats 3. a theme 4. a mestre-sala (master of ceremonies) and a porta-bandeira (flag-bearer).

Notable early composers and singers of Samba (sambistas) included Pixinguinha, Cartola, Ataulfo Alves and Jamelão among men and Clementina de Jesus, Carmelita Madriaga, Dona Ivone Lara and Jovelina Pérola Negra among women. But this is just the beginning of a long list…

The “fathers” of Samba were Rio musicians but the “mothers” of Samba were the Tias Baianas or the Aunties from Salvador da Bahia (a smaller though culturally rich city further up the Atlantic Coast). Hilária Batista de Almeida, also known as Tia Ciata (1854-1924), was born in Bahia but lived in Rio de Janeiro from the 1870s onward. Involved in persecuted “roots” rituals, she became a Mãe Pequena or Little Mother – Iyakekerê in the Yoruba language – one type of venerated priestess in the Afro-Brazilian religion, Candomblé. The Bahia African rhythms that were crucial to her ceremonies at Rua Visconde de Itaúna, number 177, were incorporated into their compositions by musicians such as Pixinguinha and Donga who were used to playing the maxixe (a 19th-century tango-like dance still popular in Rio in the early 20th century). That musical fusion was the birth of samba carioca – the early Samba sound of Rio. Pelo Telefone (“Over the Telephone”), from 1917, the humorous lyrics of which concern a gambling house (casa de jogo do bicho) and someone waiting for a telephone call tipping him off that the police are about to carry out a raid, is considered the first true Samba song.

ZP_Os Oito Batutas_The Eight Batons or Eight Cool Guys_around 1920. These Rio musicians had played maxixes and choros for bourgeois theatre-goers in the lobby at intermissions. They began to add ragtime and foxtrot numbers, the latest American imports. But in their spare time, under the influence of the Afro-Brazilian Tias Baianas, they were already synthesizing a new music, the Samba carioca…

As in Trinidad with “rival” Calypsonians and in Mexico with musical “duels” between Cantantes de Ranchera, so in Brazil there were Samba compositions in which musicians responded to one another. It was during the 1930s that White Brazilian composers began to absorb the Samba and alter its lyrical content…and gradually the special sound of Rio’s favelas (via Bahia) became the national music of Brazil…We are grateful to Bryan McCann for the following translations of two vintage Samba lyrics from Portuguese into English.

.

Wilson Batista (Black sambista, 1913 – 1968)

“Kerchief around my neck” (1933)

.

My hat tilted to the side

Wood-soled shoe dragging

Kerchief around my neck

Razor in my pocket

I swagger around

I provoke and challenge

I am proud

To be such a vagabond

.

I know they talk

About this conduct of mine

I see those who work

Living in misery

I’m a vagabond

Because I had the inclination

I remember, as a child I wrote samba songs

(Don’t mess with me, I want to see who’s right… )

My hat tilted to the side

Wood-soled shoe dragging

Kerchief around my neck

Razor in my pocket

I swagger around

I provoke and challenge

I am proud

To be such a vagabond

.

And they play

And you sing

And I don’t give in!

. . .

Wilson Batista

“Lenço no pescoço”

.

Meu chapéu do lado

Tamanco arrastando

Lenço no pescoço

Navalha no bolso

Eu passo gingando

Provoco e desafio

Eu tenho orgulho

Em ser tão vadio

.

Sei que eles falam

Deste meu proceder

Eu vejo quem trabalha

Andar no miserê

Eu sou vadio

Porque tive inclinação

Eu me lembro, era criança

Tirava samba-canção

(Comigo não, eu quero ver quem tem razão…)

.

E eles tocam

E você canta

E eu não dou!

. . .

A response-Samba to Batista’s…

Noel Rosa (White sambista, 1910 – 1937)

“Idle Youth” (1933)

.

Stop dragging your wood-soled shoe

Because a wood-soled shoe was never a sandal

Take that kerchief off your neck

Buy dress shoes and a tie

Throw out that razor

It just gets in your way

With your hat cocked, you slipped up

I want you to escape from the police

Making a samba-song

I already gave you paper and a pencil

“Arrange” a love and a guitar

Malandro is a defeatist word

What it does is take away

All the value of sambistas

I propose, to the civilized people,

To call you not a malandro

But rather an idle youth.

.

Malandro in Brazil meant: rogue, scoundrel, street-wise swindler

. . .

Noel Rosa

“Rapaz folgado”

Deixa de arrastar o teu tamanco

Pois tamanco nunca foi sandália

E tira do pescoço o lenço branco

Compra sapato e gravata

Joga fora esta navalha que te atrapalha

Com chapéu do lado deste rata

Da polícia quero que escapes

Fazendo um samba-canção

Já te dei papel e lápis

Arranja um amor e um violão

Malandro é palavra derrotista

Que só serve pra tirar

Todo o valor do sambista

Proponho ao povo civilizado

Não te chamar de malandro

E sim de rapaz folgado.

ZP_Irmandade da Boa Morte_Sisterhood of the Good Death_women devotees of Candomblé in contemporary Bahia_photo by Jill Ann Siegel

For those who observe Lent…just a reminder: next week, February 13th, is Ash Wednesday.

–But up until then … … !

And so, tonight, Friday February 8th, the mayor of Rio will hand over “the keys to the city” to Rei Momo, King Momo (from the Greek Momus – the god of satire and mockery) a.k.a. The Lord of Misrule and Revelry. A symbolic act signifying that the largest party in the world is about to begin. Enjoy!

. . . . .

“Mind is your only ruler – sovereign”: Marcus Garvey and Bob Marley: “Emancípense de la esclavitud mental; nadie más que nosotros puede liberar nuestras mentes.”

Posted: February 6, 2013 Filed under: Bob Marley, Emancípense de la esclavitud mental: Marcus Garvey + Bob Marley y su Canción de Redención, English, Spanish | Tags: Black History Month poems Comments Off on “Mind is your only ruler – sovereign”: Marcus Garvey and Bob Marley: “Emancípense de la esclavitud mental; nadie más que nosotros puede liberar nuestras mentes.”

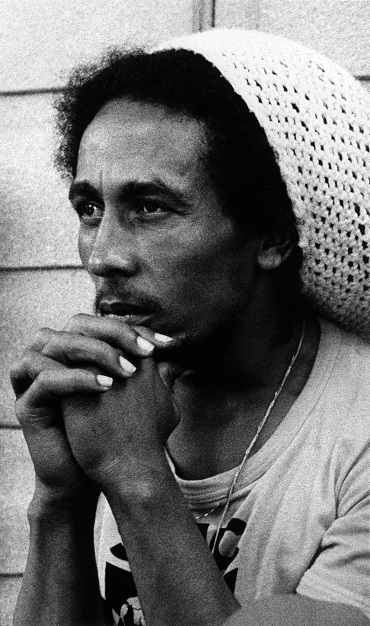

ZP_Marcus Garvey, 1887 – 1940_Jamaican orator, Black Nationalist and promoter of Pan-Africanism in the Diaspora

“Redemption Song”, from Bob Marley and The Wailers final studio album (1980), was unlike anything Marley had recorded previously. There is no reggae in in it, rather it is a kind of folksong / spiritual and just him singing with an acoustic guitar. The exhortation to “emancipate yourselves from mental slavery, none but ourselves can free our minds” was taken directly from a famous speech that fellow Jamaican and Pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey gave in Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1937. Garvey published the speech in his Black Man magazine. He had said: “We are going to emancipate ourselves from mental slavery because whilst others might free the body, none but ourselves can free the mind. Mind is your only ruler, sovereign. The man who is not able to develop and use his mind is bound to be the slave of the other man who uses his mind…” Bob Marley was born on this day, February 6th, in 1945. He developed cancer in 1977 but for three years did not seek treatment because of his Rastafarian beliefs; was the illness perhaps Jah’s will? He died in 1981, at the age of 36.

At Marley’s funeral Jamaican Prime Minister Edward Seaga eulogized him thus: “His voice was an omnipresent cry in our electronic world. His sharp features, majestic looks, and prancing style a vivid etching on the landscape of our minds. Bob Marley was never seen. He was “an experience” – which left an indelible imprint with each encounter. Such a man cannot be erased from the mind. He is part of the collective consciousness of the nation.”

.

Robert Nesta ‘Bob’ Marley

“Redemption Song”

.

Old pirates, yes, they rob I;

Sold I to the merchant ships,

Minutes after they took I

From the bottomless pit.

But my hand was made strong

By the hand of the Almighty.

We forward in this generation

Triumphantly.

Won’t you help to sing

These songs of freedom?

‘Cause all I ever have:

Redemption songs,

Redemption songs.

.

Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery;

None but ourselves can free our minds.

Have no fear for atomic energy,

‘Cause none of them can stop the time.

How long shall they kill our prophets,

While we stand aside and look?

Ooo,

Some say it’s just a part of it:

We’ve got to fulfil The Book.

.

Won’t you help to sing

These songs of freedom?

‘Cause all I ever have:

Redemption songs,

Redemption songs,

Redemption songs.

.

Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery;

None but ourselves can free our minds.

Woah, have no fear for atomic energy,

‘Cause none of them can stop the time.

How long shall they kill our prophets,

While we stand aside and look?

Yes, some say it’s just a part of it:

We’ve got to fulfil The Book.

Won’t you help to sing

These songs of freedom?

‘Cause all I ever had:

Redemption songs,

Yes, all I ever had:

Redemption songs:

These songs of freedom,

Songs of freedom.

. . .

Canción de Redención, del disco final (1980) grabado por Bob Marley y “Los hombres plañideros”, es algo diferente: una canción folklórica muy íntima – con solamente una voz y una guitarra acústica – y no es canción de reggae. Cuando Marley cantó este “canto” que es también una exhortación, ya sufría del cáncer, y ahora, en el año 2013 – más de tres décadas después de su muerte – las letras de Redención parecen como buen consejo para vivir con dignidad en el mundo actual.

Las palabras Emancípense de la esclavitud mental – nadie más que nosotros puede liberar nuestras mentes son pasajes de una declaración famosa del activista jamaiquino Negro-Nacionalista Marcus Garvey (1887-1940). En Jamaica la gente cree que la religión rastafari (la fe de Bob Marley) es en parte consecuencia de las ideas de Garvey; él anunció la llegada de un rey, el emperador Haile Selassie de Etiopía. En hecho, Garvey aseguró a sus seguidores: “Miren a Africa cuando un rey negro sea coronado – éso significa que la liberación está cerca”.

Pero “la llegada de un rey” no resuelve todo el misterio irónico de la Vida – como la muerte de un hombre casi joven – y de gran don.

Edward Seaga, el primer ministro de Jamaica, pronunció el elogio al funeral de Bob Marley. Dijo: “Su voz fue un grito omnipresente en nuestro mundo electrónico. Sus rasgos afilados, su aspecto majestuoso y su forma de moverse se han grabado intensamente en el paisaje de nuestra mente. Bob Marley nunca fue visto. Fue “una experiencia” que dejó una huella indeleble en cada encuentro. Un hombre así no se puede borrar de la mente. Él es parte de la conciencia colectiva de la nación.”

.

Robert Nesta ‘Bob’ Marley (6 de febrero, 1945 – 1981)

“Canción de Redención”

.

Viejos piratas, sí, que me roban a yo;

Vendido yo a los buques mercantes,

Minutos después de que tomé a yo

Desde el pozo sin fondo.

Pero mi mano fue hecha fuerte

Por la mano del Todopoderoso.

Avanzamos adelante en esta generación

– Triunfante.

¿No le gustaría ayudar a cantar

Estas canciones de libertad?

Porque todo lo que tengo – alguna vez:

Las canciones de redención,

Canciones de la redención.

.

Emancípense de la esclavitud mental;

Nadie más que nosotros puede liberar nuestras mentes.

No tenga miedo de la energía atómica,

Ninguno de ellos puede parar el tiempo.

¿Por cuánto tiempo van a matar a nuestros profetas,

A pesar de que un lado para mirar?

Ooo,

Algunos dicen que es sólo una parte de todo:

Tenemos que cumplir con El Libro.

.

¿No le gustaría ayudar a cantar

Estas canciones de libertad?

Porque todo lo que tengo – alguna vez:

Las canciones de redención,

Canciones de redención,

Canciones de la redención.

.

Emancípense de la esclavitud mental;

Nadie más que nosotros puede liberar nuestras mentes.

Ay,

No tenga miedo de la energía atómica,

Ninguno de ellos puede parar el tiempo..

¿Por cuánto tiempo van a matar a nuestros profetas,

A pesar de que un lado para mirar?

Sí, algunos dicen que es sólo una parte de todo:

Tenemos para cumplir con El Libro.

¿Usted, no va a tener que cantar

Estas canciones de libertad?

Porque todo lo que tuve – alguna vez:

Las canciones de redención.

Todo lo que yo tuve – alguna vez:

Canciones de redención, ah sí –

Estas canciones de libertad,

Canciones de la libertad.

. . . . .

“Viva y no pare” / “Live and don’t hold back”: Nicolás Guillén + el Yoruba de Cuba / the Yoruba from Cuba

Posted: February 5, 2013 Filed under: English, Nicolás Guillén, Nicolás Guillén + el Yoruba de Cuba / the Yoruba from Cuba, Spanish, ZP Translator: Alexander Best | Tags: Black History Month poems Comments Off on “Viva y no pare” / “Live and don’t hold back”: Nicolás Guillén + el Yoruba de Cuba / the Yoruba from CubaNicolás Guillén (Cuba, 1902-1989)

A poem from “ ‘Son’ Motifs ” (1930)

“Go get some dough”

.

Get some silver,

go get some dough for us!

Cuz I’m not goin one step more:

we’re down to just rice and crackers,

that’s it.

Yeah, I know how things are,

but hey, my Guy – a person’s gotta eat:

so get some money,

go get it,

else I’m gonna beat it.

Then they’ll call me a ‘no good’ woman

and won’t want nothin’ to do with me. But

Love with Hunger? Hell no!

.

There’s so many pretty new shoes out there, dammit!

So many wristwatches, compadre!

Hell – so many luxuries we might have, my Man!

.

Translation from Spanish: Alexander Best

.

Note: ‘Son’ (meaning Sound) was the traditional Cuban music style of the early twentieth century.

It combined Spanish song and guitars with African percussion of Bantu origin. ‘Son’ was the basis upon which Salsa developed.

. . .

Del poemario “Motivos de Son” (1930)

“Búcate plata”

.

Búcate plata,

búcate plata,

poqque no doy un paso má;

etoy a arró con galleta,

na má.

Yo bien sé como etá to,

pero biejo, hay que comé:

búcate plata,

búcate plata,

poqque me boy a corré.

Depué dirán que soy mala,

y no me quedrán tratá,

pero amó con hambre, biejo.

¡qué ba!

con tanto sapato nuevo,

¡qué ba!

Con tanto reló, compadre,

¡qué ba!

Con tanto lujo, mi negro,

¡qué ba!

. . .

A poem from Sóngoro cosongo: mulatto poems (1931)

“Cane”

.

The black man

together with the plantation.

The yankee

on the plantation.

The earth

beneath the plantation.

Our blood

drains out of us!

. . .

Un poema del poemario Sóngoro cosongo: poemas mulatos (1931)

“Caña”

.

El negro

junto al cañaveral.

El yanqui

sobre el cañaveral.

La tierra

bajo el cañaveral.

¡Sangre

que se nos va!

. . .

Two poems from “West Indies, Ltd.” (1934):

“Guadaloupe, W. I., Pointe-à-Pitre”

.

The black men, working

near the steamboat. The arabs, selling,

the french, strolling, having a rest

– and the sun, burning.

.

In the harbour the sea

lies down. The air toasts

the palm trees… I scream: Guadaloupe!

but nobody answers.

.

The steamboat leaves, labouring through

the impassive waters with a foaming roar.

There the black men stay, still working,

and the arabs, selling,

and the french, strolling, having a rest

– and the sun, burning…

. . .

“Guadalupe, W. I., Pointe-à-Pitre” (1934)

.

Los negros, trabajando

junto al vapor. Los árabes, vendiendo,

los franceses, paseando y descansando

– y el sol, ardiendo.

En el puerto se acuesta

el mar. El aire tuesta

las palmeras… Yo grito: ¡Guadalupe!

pero nadie contesta.

.

Parte el vapor, arando

las aguas impasibles con espumoso estruendo.

Allá quedan los negros trabajando,

los árabes vendiendo,

los franceses, paseando y descansando

– y el sol, ardiendo…

. . .

“Riddles”

.

The teeth, filled with the morning,

and the hair, filled with the night.

Who is it? It’s him, or it’s not him?

— Black man.

.

Though she being woman and not beautiful,

you’ll do what she orders you.

Who is it? It’s him, or it’s not him?

— Hunger.

.

Slave of the slaves,

and towards the masters, tyrant.

Who is it? It’s him, or it’s not him?

— Sugar cane.

.

Noise of a hand

that never ignores the other.

Who is it? It’s him, or it’s not him?

— Almsgiving.

.

A man who is crying

going on with the laugh he learned.

Who is it? It’s him, or it’s not him?

— Me.

. . .

“Adivinanzas”

.

En los dientes, la mañana,

y la noche en el pellejo.

¿Quién será, quién no será?

— El negro.

.

Con ser hembra y no ser bella,

harás lo que ella te mande.

¿Quién será, quién no será?

— El hambre.

.

Esclava de los esclavos,

y con los dueños, tirana.

¿Quién será, quién no será?

— La caña.

.

Escándalo de una mano

que nunca ignora a la otra.

¿Quién será, quién no será?

— La limosna.

.

Un hombre que está llorando

con la risa que aprendió.

¿Quién será, quién no será?

— Yo.

. . .

Poem from “Cantos para soldados y sones para turistas (1937)

“Execution”

.

They are going to execute

a man whose arms are tied.

There are four soldiers

for the shooting.

Four silent

soldiers,

fastened up,

like the fastened-up man they’re going to kill.

— Can you escape?

— I can’t run!

— They’re gonna shoot!

— What’re we gonna do?

— Maybe the rifles aren’t loaded…

— They got six bullets of fierce lead!

— Perhaps these soldiers don’t shoot!

— You’re a fool – through and through!

.

They fired.

(How was it they could shoot?)

They killed.

(How was it they could kill?)

They were four silent

soldiers,

and an official señor

made a signal to them, lowering his saber.

Four soldiers they were,

and tied,

like the man they were to kill.

“Fusilamiento”

.

Van a fusilar

a un hombre que tiene los brazos atados.

Hay cuatro soldados

para disparar.

Son cuatro soldados

callados,

que están amarrados,

lo mismo que el hombre amarrado que van a matar.

—¿Puedes escapar?

—¡No puedo correr!

—¡Ya van a tirar!

—¡Qué vamos a hacer!

—Quizá los rifles no estén cargados…

—¡Seis balas tienen de fiero plomo!

—¡Quizá no tiren esos soldados!

—¡Eres un tonto de tomo y lomo!

.

Tiraron.

(¿Cómo fue que pudieron tirar?)

Mataron.

(¿Cómo fue que pudieron matar?)

Eran cuatro soldados

callados,

y les hizo una seña, bajando su sable,

un señor oficial;

eran cuatro soldados

atados,

lo mismo que el hombre que fueron los cuatro a

matar.

. . .

“Bourgeois”

.

The vanquished bourgeois – they don’t make me sad.

And when I think they are going to make me sad,

I just really grit my teeth, really shut my eyes.

.

I think about my long days with neither shoes and roses,

I think about my long days with neither sombrero nor

clouds,

I think about my long days without a shirt – or dreams,

I think about my long days with my prohibited skin,

I think about my long days And

.

You cannot come in, please – this is a club.

The payroll is full.

There’s no room in this hotel.

The señor has stepped out.

Looking for a girl.

Fraud in the elections.

A big dance for blind folks.

.

The first price fell to Santa Clara.

A “Tómbola” lottery for orphans.

The gentleman is in Paris.

Madam the marchioness doesn’t receive people.

Finally And

.

Given that I recall everything and

the way I recall everything,

what the hell are you asking me to do?

In addition, ask them,

I’m sure they too

recall all.

. . .

“Burgueses”

.

No me dan pena los burgueses vencidos.

Y cuando pienso que van a dar me pena,

aprieto bien los dientes, y cierro bien los ojos.

.

Pienso en mis largos días sin zapatos ni rosas,

pienso en mis largos días sin sombrero ni nubes,

pienso en mis largos días sin camisa ni sueños,

pienso en mis largos días con mi piel prohibida,

pienso en mis largos días Y

.

No pase, por favor, esto es un club.

La nómina está llena.

No hay pieza en el hotel.

El señor ha salido.

.

Se busca una muchacha.

Fraude en las elecciones.

Gran baile para ciegos.

.

Cayó el premio mayor en Santa Clara.

Tómbola para huérfanos.

El caballero está en París.

La señora marquesa no recibe.

En fin Y

Que todo lo recuerdo y como todo lo

recuerdo,

¿qué carajo me pide usted que haga?

Además, pregúnteles,

estoy seguro de que también

recuerdan ellos.

. . .

“The Black Sea”

.

The purple night dreams

over the sea;

voices of fishermen,

wet with the sea;

the moon makes its exit,

dripping all over the sea.

.

The black sea.

Throughout the night, a sound,

flows into the bay;

throughout the night, a sound.

.

The boats see it happen,

throughout the night, this sound,

igniting the chilly water.

Throughout the night, a sound,

Inside the night, this sound,

Across the night – a sound.

.

The black sea.

Ohhh, my mulatto woman of fine, fine gold,

I sigh, oh my mixed woman who is like gold and silver together,

with her red poppy and her orange blossom.

At the foot of the sea.

At the foot of the sea, the hungry, masculine sea.

.

Translation from Spanish: Alexander Best

. . .

“El Negro Mar”

.

La noche morada sueña

sobre el mar;

la voz de los pescadores

mojada en el mar;

sale la luna chorreando

del mar.

El negro mar.

Por entre la noche un son,

desemboca en la bahía;

por entre la noche un son.

Los barcos lo ven pasar,

por entre la noche un son,

encendiendo el agua fría.

Por entre la noche un son,

por entre la noche un son,

por entre la noche un son. . .

El negro mar.

Ay, mi mulata de oro fino,

ay, mi mulata

de oro y plata,

con su amapola y su azahar,

al pie del mar hambriento y masculino,

al pie del mar.

. . .

“Son” Number 6

.

I’m Yoruba, crying out Yoruba

Lucumí.

Since I’m Yoruba from Cuba,

I want my lament of Yoruba to touch Cuba

the joyful weeping Yoruba

that comes out of me.

.

I’m Yoruba,

I keep singing

and crying.

When I’m not Yoruba then

I am Congo, Mandinga or Carabalí.

Listen my friends, to my ‘son’ which begins like this:

.

Here is the riddle

of all my hopes:

what’s mine is yours,

what’s yours is mine;

all the blood

shaping a river.

.

The silk-cotton tree, tree with its crown;

father, the father with his son;

the tortoise in its shell.

Let the heart-warming ‘son’ break out,

and our people dance,

heart close to heart,

glasses clinking together

water on water with rum!

.

I’m Yoruba, I’m Lucumí,

Mandinga, Congo, Carabalí.

Listen my friends, to the ‘son’ that goes like this:

.

We’ve come together from far away,

young ones and old,

Blacks and Whites, moving together;

one is a leader, the other a follower,

all moving together;

San Berenito and one who’s obeying

all moving together;

Blacks and Whites from far away,

all moving together;

Santa María and one who’s obeying

all moving together;

all pulling together, Santa María,

San Berenito, all pulling together,

all moving together, San Berenito,

San Berenito, Santa María.

Santa María, San Berenito,

everyone pulling together!

.

I’m Yoruba, I’m Lucumí

Mandinga, Congo, Carabalí.

Listen my friends, to my ‘son’ which ends like this:

.

Come out Mulatto,

walk on free,

tell the White man he can’t leave…

Nobody breaks away from here;

look and don’t stop,

listen and don’t wait

drink and don’t stop,

eat and don’t wait,

live and don’t hold back

our people’s ‘son’ will never end!

.

Translation from Spanish: Salvador Ortiz-Carboneres

. . .

“Son número 6”

.

Yoruba soy, lloro en yoruba

lucumí.

Como soy un yoruba de Cuba,

quiero que hasta Cuba suba mi llanto yoruba;

que suba el alegre llanto yoruba

que sale de mí.

.

Yoruba soy,

cantando voy,

llorando estoy,

y cuando no soy yoruba,

soy congo, mandinga, carabalí.

Atiendan amigos, mi son, que empieza así:

.

Adivinanza

de la esperanza:

lo mío es tuyo

lo tuyo es mío;

toda la sangre

formando un río.

.

La ceiba ceiba con su penacho;

el padre padre con su muchacho;

la jicotea en su carapacho.

.

¡Que rompa el son caliente,

y que lo baile la gente,

pecho con pecho,

vaso con vaso,

y agua con agua con aguardiente!

.

Yoruba soy, soy lucumí,

mandinga, congo, carabalí.

Atiendan, amigos, mi son, que sigue así:

.

Estamos juntos desde muy lejos,

jóvenes, viejos,

negros y blancos, todo mezclado;

uno mandando y otro mandado,

todo mezclado;

San Berenito y otro mandado,

todo mezclado;

negros y blancos desde muy lejos,

todo mezclado;

Santa María y uno mandado,

todo mezclado;

todo mezclado, Santa María,

San Berenito, todo mezclado,

todo mezclado, San Berenito,

San Berenito, Santa María,

Santa María, San Berenito

todo mezclado!

.

Yoruba soy, soy lucumí,

mandinga, congo, carabalí.

Atiendan, amigos, mi son, que acaba así:

.

Salga el mulato,

suelte el zapato,

díganle al blanco que no se va:

de aquí no hay nadie que se separe;

mire y no pare,

oiga y no pare,

beba y no pare,

viva y no pare,

que el son de todos no va a parar!

. . . . .

From Arturo Schomburg to Josephine Baker

Posted: February 1, 2013 Filed under: A FEW FAVOURITES / UNA MUESTRA DE FAVORITOS, Bessie Smith, Black History Month 2 | Tags: Black History Month photographs Comments Off on From Arturo Schomburg to Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker, née Freda Josephine McDonald, was born in St. Louis in 1906. In 1921 she ventured to New York City, danced at The Plantation Club in Harlem, and became a popular and well-paid chorus girl in Broadway revues. In 1925 she travelled to Paris where she wowed ’em with her athletic elegance and fresh humour. Parisians were mad for all things “Negro” and “Exotic” so Baker shrewdly “invented” herself for France – yet somehow remained sincere and real. She became a French citizen, spied on the Nazis for her government during WW2, raised a dozen adopted children – her rainbow tribe – and, from the 1950s onward, was a tireless campaigner for Civil Rights in the U.S.A. She died peacefully in 1975 after having given a performance at the Bobino music-hall theatre in Montparnasse.

ZP_Aaron Douglas’ 1929 dustjacket illustration for The Blacker the Berry – A Novel of Negro Life, by Wallace Thurman 1902-1934

ZP_Claude McKay, 1889-1948, Jamaican-born author of the frank and intense 1928 novel, Home to Harlem

ZP_Bessie Smith, 1894 to 1937, was the biggest Blues singer of the 1920s. Her sexual frankness through the use of metaphor is an absolute marvel – even in 2013. Poet Langston Hughes would’ve been familiar with her spicy lyrics.

Bessie Smith

“Empty Bed Blues” (recorded in 1928, lyrics by Smith)

.

I woke up this morning with a awful aching head

I woke up this morning with a awful aching head

My new man had left me, just a room and a empty bed

.

Bought me a coffee grinder that’s the best one I could find

Bought me a coffee grinder that’s the best one I could find

Oh, he could grind my coffee, ’cause he had a brand new grind

.

He’s a deep sea diver with a stroke that can’t go wrong

He’s a deep sea diver with a stroke that can’t go wrong

He can stay at the bottom and his wind holds out so long

.

He knows how to thrill me and he thrills me night and day

Oh, he knows how to thrill me, he thrills me night and day

He’s got a new way of loving, almost takes my breath away

.

Lord, he’s got that sweet somethin’ and I told my girlfriend Lou

He’s got that sweet somethin’ and I told my girlfriend Lou

From the way she’s raving, she must have gone and tried it too

.

When my bed get empty make me feel awful mean and blue

When my bed get empty make me feel awful mean and blue

My springs are getting rusty, sleeping single like I do

.

Bought him a blanket, pillow for his head at night

Bought him a blanket, pillow for his head at night

Then I bought him a mattress so he could lay just right

.

He came home one evening with his spirit way up high

He came home one evening with his spirit way up high

What he had to give me, make me wring my hands and cry

.

He give me a lesson that I never had before

He give me a lesson that I never had before

When he got to teachin’ me, from my elbow down was sore

.

He boiled my first cabbage and he made it awful hot

He boiled my first cabbage and he made it awful hot

When he put in the bacon, it overflowed the pot

.

When you git good lovin’, never go and spread the news

Yes, he’ll double-cross you, and leave you with them empty bed blues.

ZP_Gladys Bentley, 1907 – 1960, in a retouched and colourized 1920s photograph_Bentley was an openly lesbian Blues singer who often performed at Clam House, a gay speakeasy in Harlem.

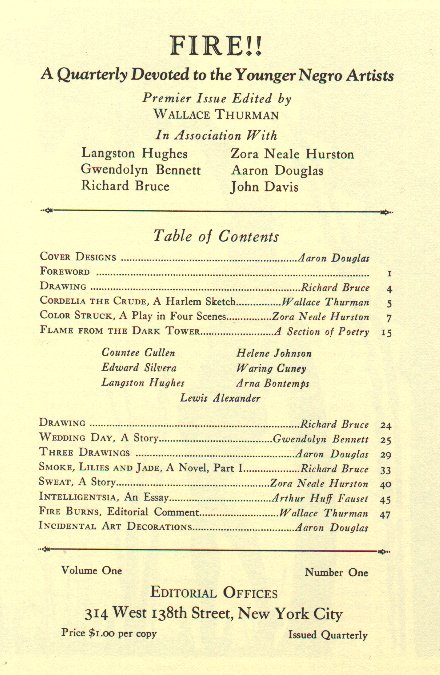

ZP_Fire!, the 1926 one-issue-only Harlem literary journal that appalled and offended the Black middle-class

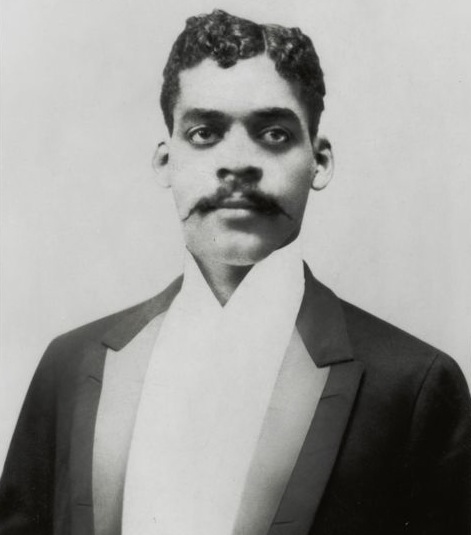

ZP_Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, 1874 – 1938_PuertoRican-born and mixed race, he settled in Harlem in the 1890s and was determined to untangle and reveal the African thread in the fabric of the Americas. Historian and activist, Schomburg was one of the intellectual backbones of The Harlem Renaissance.

ZP_The Crisis – A Record of the Darker Races, founded in 1910, was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s monthly journal. Edited by W. E. B. Du Bois, it featured, in a 1921 issue, the first published poem of a 19 year old Langston Hughes – The Negro Speaks of Rivers.

Love poems, Blues poems – from The Harlem Renaissance

Posted: February 1, 2013 Filed under: English, English: Black Canadian / American, Langston Hughes, Love poems and Blues poems – from The Harlem Renaissance | Tags: Black History Month poems Comments Off on Love poems, Blues poems – from The Harlem RenaissanceLove poems, Blues poems – from The Harlem Renaissance:

Langston Hughes verses composed between 1924 and 1930:

. . .

“Subway Face”

.

That I have been looking

For you all my life

Does not matter to you.

You do not know.

.

You never knew.

Nor did I.

Now you take the Harlem train uptown;

I take a local down.

(1924)

. . .

“Poem (2)” (To F. S.)

.

I loved my friend.

He went away from me.

There’s nothing more to say.

The poem ends,

Soft as it began –

I loved my friend.

(1925)

. . .

“Better”

.

Better in the quiet night

To sit and cry alone

Than rest my head on another’s shoulder

After you have gone.

.

Better, in the brilliant day,

Filled with sun and noise,

To listen to no song at all

Than hear another voice.

. . .

“Poem (4)” (To the Black Beloved)

.

Ah,

My black one,

Thou art not beautiful

Yet thou hast

A loveliness

Surpassing beauty.

.

Oh,

My black one,

Thou art not good

Yet thou hast

A purity

Surpassing goodness.

.

Ah,

My black one,

Thou art not luminous

Yet an altar of jewels,

An altar of shimmering jewels,

Would pale in the light

Of thy darkness,

Pale in the light

Of thy nightness.

. . .

“The Ring”

.

Love is the master of the ring

And life a circus tent.

What is this silly song you sing?

Love is the master of the ring.

.

I am afraid!

Afraid of Love

And of Love’s bitter whip!

Afraid,

Afraid of Love

And Love’s sharp, stinging whip.

.

What is this silly song you sing?

Love is the master of the ring.

(1926)

. . .

“Ma Man”

.

When ma man looks at me

He knocks me off ma feet.

When ma man looks at me

He knocks me off ma feet.

He’s got those ‘lectric-shockin’ eyes an’

De way he shocks me sho is sweet.

.

He kin play a banjo.

Lordy, he kin plunk, plunk, plunk.

He kin play a banjo.

I mean plunk, plunk…plunk, plunk.

He plays good when he’s sober

An’ better, better, better when he’s drunk.

.

Eagle-rockin’,

Daddy, eagle-rock with me.

Eagle rockin’,

Come an’ eagle-rock with me.

Honey baby,

Eagle-rockish as I kin be!

. . .

“Lament over Love”

.

I hope my child’ll

Never love a man.

I say I hope my child’ll

Never love a man.

Love can hurt you

Mo’n anything else can.

.

I’m goin’ down to the river

An’ I ain’t goin’ there to swim;

Down to the river,

Ain’t goin’ there to swim.

My true love’s left me

And I’m goin’ there to think about him.

.

Love is like whiskey,

Love is like red, red wine.

Love is like whiskey,

Like sweet red wine.

If you want to be happy

You got to love all the time.

.

I’m goin’ up in a tower

Tall as a tree is tall,

Up in a tower

Tall as a tree is tall.

Gonna think about my man –

And let my fool-self fall.

(1926)

. . .

“Dressed Up”

.

I had ma clothes cleaned

Just like new.

I put ’em on but

I still feels blue.

.

I bought a new hat,

Sho is fine,

But I wish I had back that

Old gal o’ mine.

.

I got new shoes –

They don’t hurt ma feet,

But I ain’t got nobody

For to call me sweet.

. . .

“To a Little Lover-Lass, Dead”

.

She

Who searched for lovers

In the night

Has gone the quiet way

Into the still,

Dark land of death

Beyond the rim of day.

.

Now like a little lonely waif

She walks

An endless street

And gives her kiss to nothingness.

Would God his lips were sweet!

. . .

“Harlem Night Song”

.

Come,

Let us roam the night together

Singing.

.

I love you.

Across

The Harlem roof-tops

Moon is shining.

Night sky is blue.

Stars are great drops

Of golden dew.

.

Down the street

A band is playing.

.

I love you.

.

Come,

Let us roam the night together

Singing.

. . .

“Passing Love”

.

Because you are to me a song

I must not sing you over-long.

.

Because you are to me a prayer

I cannot say you everywhere.

.

Because you are to me a rose –

You will not stay when summer goes.

(1927)

. . .

“Desire”

.

Desire to us

Was like a double death,

Swift dying

Of our mingled breath,

Evaporation

Of an unknown strange perfume

Between us quickly

In a naked

Room.

. . .

“Dreamer”

.

I take my dreams

And make of them a bronze vase,

And a wide round fountain

With a beautiful statue in its centre,

And a song with a broken heart,

And I ask you:

Do you understand my dreams?

Sometimes you say you do

And sometimes you say you don’t.

Either way

It doesn’t matter.

I continue to dream.

(1927)

. . .

“Lover’s Return”

.

My old time daddy

Came back home last night.

His face was pale and

His eyes didn’t look just right.

.

He says, “Mary, I’m

Comin’ home to you –

So sick and lonesome

I don’t know what to do.”

.

Oh, men treats women

Just like a pair o’ shoes –

You kicks ’em round and

Does ’em like you choose.

.

I looked at my daddy –

Lawd! and I wanted to cry.

He looked so thin –

Lawd! that I wanted to cry.

But the devil told me:

Damn a lover

Come home to die!

(1928)

. . .

“Hurt”

.

Who cares

About the hurt in your heart?

.

Make a song like this

for a jazz band to play:

Nobody cares.

Nobody cares.

Make a song like that

From your lips.

Nobody cares.

. . .

“Spring for Lovers”

.

Desire weaves its fantasy of dreams,

And all the world becomes a garden close

In which we wander, you and I together,

Believing in the symbol of the rose,

Believing only in the heart’s bright flower –

Forgetting – flowers wither in an hour.

(1930)

. . .

“Rent-Party Shout: For a Lady Dancer”

.

Whip it to a jelly!

Too bad Jim!

Mamie’s got ma man –

An’ I can’t find him.

Shake that thing! O!

Shake it slow!

That man I love is

Mean an’ low.

Pistol an’ razor!

Razor an’ gun!

If I sees man man he’d

Better run –

For I’ll shoot him in de shoulder,

Else I’ll cut him down,

Cause I knows I can find him

When he’s in de ground –

Then can’t no other women

Have him layin’ round.

So play it, Mr. Nappy!

Yo’ music’s fine!

I’m gonna kill that

Man o’ mine!

(1930)

. . . . .

In the manner of all great poets Langston Hughes (February 1st, 1902 – 1967) wrote love poems (and love-blues poems), using the voices and perspectives of both Man and Woman. In addition to such art, Hughes’ homosexuality, real though undisclosed during his lifetime, probably was responsible for the subtle and highly-original poet’s voice he employed for three of the poems included here: Subway Face, Poem (2), and Desire. Hughes was among a wealth of black migrants born in The South or the Mid-West who gravitated toward Harlem in New York City from about 1920 onward. Along with Countee Cullen, Zora Neale Hurston, Wallace Thurman and many others, Hughes became part of The Harlem Renaissance, that great-gorgeous fresh-flowering of Black-American culture.

. . . . .

From The Black Patti to Mamie Smith

Posted: February 1, 2013 Filed under: A FEW FAVOURITES / UNA MUESTRA DE FAVORITOS, Black History Month 1 | Tags: Black History Month photographs Comments Off on From The Black Patti to Mamie Smith

ZP_Mamie Smith, 1883 to 1946, vaudevillian and Blues singer who was the first black woman to cut a Blues record. In 1920, in New York City, she recorded the first million-seller by a black singer – two songs by Perry Bradford – Crazy Blues and It’s Right Here For You – If You Don’t Get It, T’ain’t No Fault of Mine.

ZP_Gertrude Ma Rainey, 1886 to 1939, and a Suitor, in The Rabbit Foot’s Minstrels touring music and theatre company, around 1915_Rainey was one of the earliest Blues singers and among the first to record.

ZP_Buddy Bolden (top row, second from right) and his Orchestra, 1905. New Orleans native Bolden combined a looser form of Ragtime with Blues, and by adding brass instruments from marching bands to these rhythms and moods he helped to create Jazz.

ZP_Scott Joplin, 1867 to 1917, was one of a handful of ingenious musical synthesizers of the 1890s, blending John Philip Sousa style marches with African syncopation, thereby creating Ragtime music. His Maple Leaf Rag from 1899 was played on brothel and parlour pianos across the U.S.A._Sheet music for Pine Apple Rag, 1908.

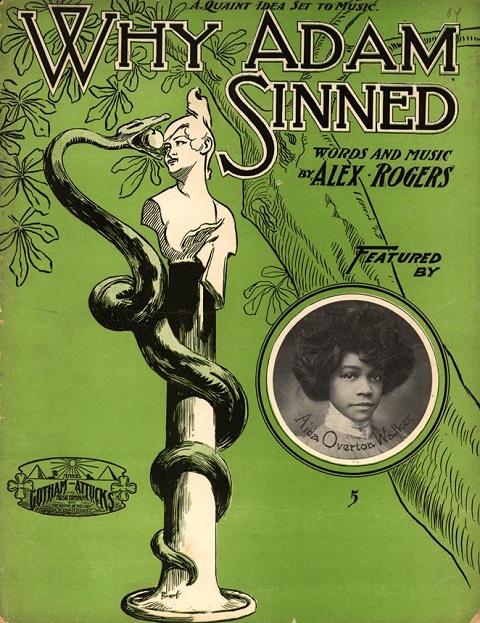

“Why Adam Sinned”

(words and music by Alex Rogers, 1876-1930)

.

I heeard da ole folks talkin’ in our house da other night

‘Bout Adam in da scripchuh long ago.

Da lady folks all ‘bused him, sed he knowed it wus’n right

an’ ‘cose da men folks dey all sed “Dat’s so.”

I felt sorry fuh Mistuh Adam, an’ I felt like puttin’ in,

‘Cause I knows mo’ dan dey do all ’bout whut made Adam sin.

.

Adam nevuh had no Mammy fuh to take him on her knee

An’ teach him right fum wrong an’ show him

Things he ought to see.

I knows down in my heart – he’d-a let dat apple be,

But Adam nevuh had no dear old Ma-am-my.

.

He nevuh knowed no chilehood roun’ da ole log cabin do’,

He nevuh knowed no pickaninny life.

He started in a great big grown up man, an’ whut is mo’,

He nevuh had da right kind uf a wife.

Jes s’pose he’d had a Mammy when dat temptin’ did begin

An’ she’d-a come an’ tole him

“Son, don’ eat dat – dat’s a sin.”

.

But Adam nevuh had no Mammy fuh to take him on her knee

An’ teach him right fum wrong an’ show him

Things he ought to see.

I knows down in my heart he’d-a let dat apple be,

But Adam nevuh had no dear old Ma-am-my.

ZP_Aida Overton Walker in the all-black Broadway musical, In Dahomey, with lyrics by Paul Laurence Dunbar, 1903

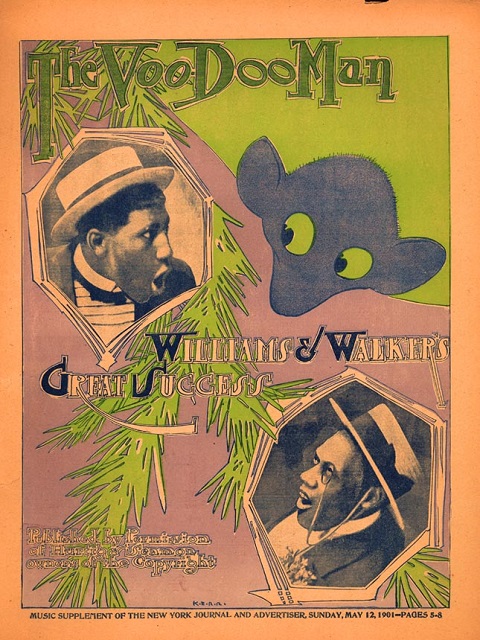

ZP_The Voodoo Man_a song sung by Bert Williams and George Walker, 1901_This black vaudevillian duo had performed Cake-Walks wearing burnt-cork blackface during the 1890s.

ZP_Madame Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones a.k.a. The Black Patti, 1869 – 1933_Madame Jones was an opera singer who gave recitals of arias by Gounod and Verdi along with sentimental songs such as The Last Rose of Summer. She was the first black singer to perform at Carnegie Hall. Though she tried for leads at The Met, the institutional racism of the era prevented her from rising as she should’ve in the world of Opera. Finding herself barred from most concert halls she formed her own classical-music and variety-act touring company, The Black Patti Troubadours, which gave her a comfortable living until around 1915, when the concert-going public’s musical tastes shifted more toward Tin Pan Alley’s bluesy or jazzy pop-songs. Poster from 1899